The Wheel of Intelligent

Leadership™: The Inner Core

Do you remember when you first learned to drive a stick-shift automobile? I do. My memories are very sad indeed! In 1973, at the age of 16, I was living with my family outside of Boston in the middle-class suburb of Waltham. I learned how to drive a stick shift on a black Volkswagen Beetle, no heat, no horn, and I think the car had half a floor board! I recall the fateful day well—when my dad said to me, “Do you want to learn how to drive a stick shift?”

I remember uttering something pretty idiotic like, “Dad, that’s not even a car; it’s a lawn mower!” My dad replied, “Get in the car. We are going to the high school parking lot.” I said, “Why?” My dad said, “Because the parking lot is BIG!” I said, “That’s negative. . . .” You get the drift, we’ve all been there.

When we arrived at the Waltham High School parking lot, my dad, still behind the wheel, started to show me the procedure—depressing the clutch, shifting, and so on. “So,” my dad said, “What do you think?” Being a teenager and, of course, overconfident, I replied, “Move over!”

Until September 1997 when my dad passed away, I often told him how impressed I was with the initial patience he displayed. Emphasis is on the word initial because, when I finally took the wheel on the driver’s side, I’m not sure how or why, but I froze. I have to tell you that my dad’s initial impatience quickly turned into incredible impatience. Understand that, my dad, Dominic F. Mattone, was a tough Italian from Brooklyn, a son of immigrant parents who were also tough. Get the picture? After about 10 seconds of the freeze, I felt a smack on my shoulder. I was afraid to look. Another 10 seconds passed. Then another smack. Finally, I looked at him and he said, “Do something! Do something. Now!”

I said, “I don’t know what to do!” He growled, “Turn the key and step down on the #%&*#$% clutch!” I looked down to find the clutch, and I couldn’t believe my eyes. I gasped, “Dad, there’s three pedals. I only have two feet. There’s no way anyone with two feet can drive a car with three pedals. There’s no way; I can’t do it!”

As time went on that fateful day—and it was a very long day—something magical started to happen. Yes, I was a brash teenager, but I was also a product of my mom and dad—both very loving and caring parents. They were experts in tough love well before we came to know and understand the term. I was pretty tough too; at least I thought I was! I could always handle my dad’s feedback because I knew it was out of love.

So what did I do? I became somewhat callous to the feedback and started to focus on the task at hand. I came out of my comfort zone. Eventually, I put one foot on the clutch and turned the key. Success! I again came out of my comfort zone and maneuvered the shift to first gear with my foot still on the clutch. Success! And then I placed my right foot on the accelerator and slowly let the clutch out with my left foot. The car miraculously started to move. Success! You get the picture.

As I generated little successes, these so-called references—which make up part of our self-concept and are either positively or negatively charged, just like protons and electrons—became positively charged. Positively charged references have a significant impact on positively altering beliefs and thoughts; they enable you to effectively dispute the validity of initial negative thoughts. So my initial belief (“I can’t do it!”) gave way to a new, stronger, and positive belief: “I can do it!” That was because I was doing it and experiencing enough success to reinforce the validity of the new belief and successfully dispute the earlier negative belief.

One of the biggest challenges leaders today face is knowing how to interpret their failures or even difficult situations and people. Sometimes leaders’ reservoirs of references are so negatively charged that they begin to believe that nothing they do will actually make things better. Some leaders, when faced with really tough situations and people, actually believe they are helpless. Their reaction, as understandable as it might be, is nothing more than a way to avoid fear and to preserve their self-concept in the face of a tough challenge. When leaders indulge in these types of defense mechanisms, they block their ability to act in constructive ways, as well as their ability to solve issues and to mature as executives. This destructive mindset is called learned helplessness, and it is at the root of immature leadership behavior.

I had really good reason to believe I couldn’t drive a stick shift, not the least of which was that I had never done it. My reference reservoir was missing any similar positively charged experience, so there was real validity to my belief, even though my initial thoughts were positive. This is the reason positive thoughts in and of themselves are a necessary but insufficient condition for propelling leaders to new levels of maturity. Positive thoughts need to be turned into firmly held beliefs by creating positively charged references that support the validity of those positive thoughts. Very little good can come from continually telling yourself, “I’m good,” “I’m confident,” “I’m worthy of success” if your words are incongruent with an opposing reference system. The only way to create positively charged references is to create successes. And you can’t create successes without taking a risk, without taking action aimed at providing support for your thoughts. I initially failed in my attempt to drive a stick shift; however, deep down I did believe I would succeed—despite no reference in support—I remembered my friends who had successfully learned. If they could do it, so could I.

For the leaders or future leaders who need to build reference reservoirs, great benefit can be derived by searching for positively charged references outside their own reservoirs. This is an especially helpful exercise if you have few positive references to draw on. In this case, you—the leader or future leader—must seek out, identify with, and vicariously experience the positively charged references of those who have successfully met challenges like those you are facing. The process begins with your reaching out and interviewing other successful leaders and asking them to explain, in real specific terms and in vivid detail, the challenges they have faced, what they did to gain a better understanding of their challenges, and what they did to work through them, including what they were thinking, feeling, and doing. I have found that this kind of mentoring element, if done in vivid detail, can have a powerful vicarious impact on the leader who lacks critical references. Ultimately, through mentoring, they begin to adopt a positive thinking and belief pattern that leads to taking positive action. All too often when leaders experience setbacks, they perceive their efforts as futile and develop the terminal discouragement of learned helplessness. When mature leaders experience setbacks, however, they refuse to allow this to happen. When mature leaders fail, they interpret the pain associated with the setback to be less permanent than do immature leaders. While immature leaders use words such as always (“It’s always going to be this bad”) or never (“It’s never going to improve”), mature leaders see and phrase their setbacks as temporary. Conversely, when immature leaders succeed, they tend to see their success as being temporary, whereas mature leaders will interpret positive situations as being permanent.

Another difference between mature and immature leaders (i.e., those with optimistic belief systems versus those with pessimistic belief systems) is that immature leaders tend to associate their setbacks and accompanying pain in personal terms: “It’s my fault!” “I should have done this!” Or they externalize the blame for their setback: “It’s your fault!” “You are responsible for this!” Mature leaders, on the other hand, tend not to overly personalize or project; rather, they adopt a problem-solving mindset: “Why did this happen?” “What are we going to do to solve the problem?”

Both current and emerging leaders must identify the unique strengths that they individually embody. As a leader, you must continually nurture, strengthen, and leverage your talents in order to become the absolute best leader you can while helping your organization achieve its strategic goals. I want you to consider your strengths as gifts; just like development needs, your gifts need to be attended to, developed, cultivated, shaped, rounded, and unleashed. So often, as I work with organizations and leaders, I find too much time and focus being placed on weaknesses and development needs instead of strengths. If you bench a perennial 300 batter in Major League Baseball, like an Albert Pujols, for one week, and you tell him he can neither hit in a game nor practice his hitting, I will guarantee that, when placed back in the lineup, he will perform poorly for a few days until he builds his repetitions back up. Leadership skills, like hitting, are very fine skills that can be enhanced only through positive repetition.

In Appendix D, when you read about building your Individual Development Plan, you will learn how to identify your indisputable leadership strengths and surprise strengths—your gifts as a leader that you must continue to strengthen. As a leader, you must also focus on identifying, in partnership with your external stakeholders, those unique development needs—indisputable and surprise development needs that will also need to be addressed. You will learn how to do this as well.

The most effective way for you to change how you view yourself and what you are capable of becoming is by changing your reference reservoir. This means learning to succeed. The more successes you can create—the more times you are able to step into that Volkswagen and drive it successfully—the more chances you will have to interpret your success as permanent, pervasive, and personal. The key to successfully internalizing these critical connections is tied to how often and how effectively you create more positively charged references. As you continue to create such references, you are faced with no choice but to interpret both the causes and consequences of those references (which are positive) in permanent, pervasive, and personal terms. At the same time, as you continue adding experiences and references to help you build a stronger, more powerful reference reservoir, you also, by definition, begin to correctly interpret whatever inevitable setbacks and failures you experience as less permanent, pervasive, and personal. All leaders must have the courage to take reasonable risks, make positive choices, accept the consequences of their behavior, course-correct, course-correct again, and never give up in their pursuit of positive constructive change for themselves and their organizations.

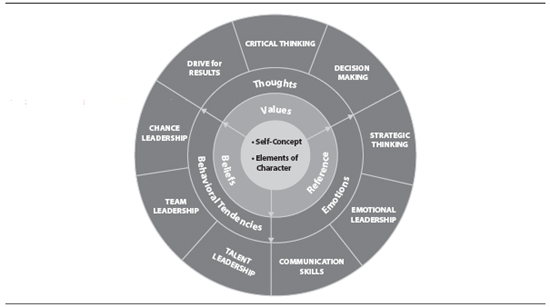

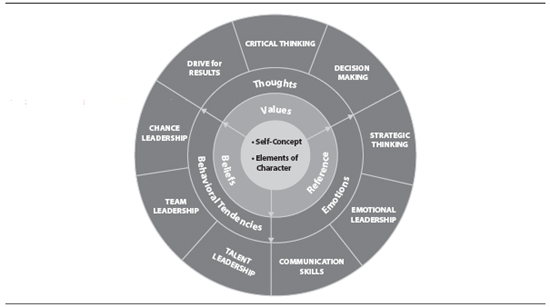

Achieving this is certainly easier said than done. However, a great place to start is with a positive, self-affirming value system and the development of a strong inner core. Notice in the Wheel of Intelligent Leadership™ (Exhibit 3.1) that your self-concept is truly multifaceted and complex. It consists of many elements, including what was just discussed: your reference reservoir and belief system. But it also includes your value system, within which I always see your elements of character play out. Once you have isolated your value system, you have also isolated your character; these two facets are intertwined and cannot be separated. In Mark Rutland’s, book, Character Matters, he defines character:

EXHIBIT 3.1: JOHN MATTONE’S WHEEL OF INTELLIGENT LEADERSHIP™

The word character is from a Latin root that means “engraved.” A life, like a block of granite carved upon with care or hacked at with reckless disregard, will in the end be either a masterpiece or marred rubble. Character, the composite of values and virtues etched in that living stone, will define its true worth. No cosmetic enhancement and no decorative drapery can make useless stone into enduring art. Only character can do that.

Character has six elements:

1. Courage

2. Loyalty

3. Diligence

4. Modesty

5. Honesty

6. Gratitude

True courage—noble courage, the authentic, spontaneous act of self-sacrificial concern for the defenseless—is not fanaticism but character. Courage is not the feeling of fearlessness. It is rather the willingness of mind necessary to act out of conviction rather than feeling. Many leaders feel quite fearless but act sometimes in a cowardly manner. Conversely, I have worked with many leaders who are fearful yet behave with incredible courage. Great leaders are courageous. Courage goes beyond valor. In fact, heroism and courage are not synonymous because everyday acts of heroism are acts of impulse rather than true character. The measure of true character is consistency. We all know business heroes, public heroes, or sports heroes who were bold enough to make a heroic mark but who could not sustain their heroism over time. They misstep or fall prey to controversy, financial ruin, and criminal activity. These people were never truly courageous; they were brave at only one point in time.

Courage is the greatest character element any leader must possess because, in the face of crisis, it is the catalytic agent that mobilizes every other virtue. Knowing right from wrong is one thing; taking the right action based on this knowledge is another. Courageous leaders inspire their people and teams to innovate and achieve incredible new heights. Courage is the foundation for creating the will-do and must-do in people and teams.

Where has all the loyalty gone? Loyalty is the very fabric of community. Relationships cannot be developed, nurtured, or made to prosper when there is no trust to glue mutuality of commitment. When loyalty is lost, the fabric of relationship unravels. Loyalty is the willingness—because of relationship commitments—to deflect praise, admiration, and success onto others. Loyalty is a two-way street; it must function both upwardly and downwardly. In organizations, upward loyalty is shown to your boss. Are you willing to allow your boss to take credit while sometimes taking the blame? If a midlevel executive shows any disloyalty—either upward or downward—the fabric of community in that organization will begin to erode. Executive leaders must promote loyalty from the top down in order for it to become distinctly integrated in corporate culture.

Sometimes executives are faced with challenges and may be looking for the quickest, shortest way—the easiest way—to produce the greatest returns. No such ways exist. There are no shortcuts to achieving anything worthwhile. There are countless stories of CEOs, senior executives, and entrepreneurs who are quick to reinforce this undeniable notion that there is no substitute for hard work. It is crucial for emerging leaders to connect with industry veterans who are willing to share the breadth of their experiences honestly and in vivid detail. By building these connections, the inexperienced leader may vicariously experience both the positive and negatively charged references, as well as a dose of reality and perspective. Diligence is a necessary—but not sufficient—condition for achieving leadership excellence. Diligence provides leaders with a solid foundation that will minimize the depth of their setbacks. Diligent leaders are steady performers, and steady performers are finishers. However, great leaders must also strive for accountability and approach their obligations with the highest degree of sincerity. Unfortunately, many managers are spiraling down toward lower maturity because of their unwillingness to finish, their reluctance to be held accountable, and their inability to follow through on their obligations. Diligence and accountability, together, work harmoniously to provide the continuous feedback loop that is necessary for individual and organizational successes.

Modesty means living within limits. It is the opposite of being bold, that is, putting oneself forward with the sense of aggressiveness or presumption. It is the opposite of arrogance. The greatest leaders are confident. But they recognize that they are also not too good, too big, too rich, or too powerful to be open to the views and perspectives of others, especially when the information they are receiving is aimed at self- or organizational improvement initiatives. Modest leaders see fiscal and operational constraints as safeguards, not hindrances. Modest leaders are able to invoke their own limits because they realize, again through positively charged references, that greater individual and team results will be realized. Modesty is also a key counterbalancing mechanism that keeps a leader’s emotions grounded. Many leaders need to know how to accept and adopt a more modest, prudent view of themselves and of the operations they run. The key to getting these leaders to transform is helping them to see that their own need for attention is driving their arrogance and the results they are achieving. If these leaders adopt a calmer, self-accepting approach in handling challenges, they will have improved outcomes and be more effective as team leaders within their organizations.

There is a line between shrewd business and dishonesty, but that line is not nearly as fine as we think. Great leaders work hard to bend over backward for honesty because they realize truth and honesty are the pillars on which relationships, teamwork, and positive energy are built. Great leaders are comfortable missing out on deals rather than using deception to win. Great leaders would rather make a minor profit with honesty than a major one without it. Exaggerations, padded expense accounts, deliberately shaved tax forms submitted without hesitation, showing up for work late, leaving early, and theft of company property (which now reaches into the billions annually) are all acts of dishonesty. Mature leaders live and promote a truthful, aboveboard, honest existence and endeavor to replicate these ideals through the organizational environment.

Great leaders demonstrate enormous respect and appreciation for the sum of all their references (both positive and negative) because they know in their minds and hearts that the very essence of who they are is inextricably tied to the sum of their experiences. They know and respect that they have learned to grow and mature as leaders through their highs and lows, and they appreciate their reference reservoirs as nothing more than a ratio of positively charged references divided by all of their experiences. It’s a batting average. Just like a batting average, the higher the ratio is, the better, but much can be learned by striking out every now and then. In fact, a strikeout keeps us in balance, and we appreciate the hits all that much more with a healthy dose of setbacks. This is one of the great challenges I see with younger executives who desire way too much, too fast; many are just unwilling to see the value in experiencing setbacks. A setback slows them down but also teaches contrast; it teaches gratitude for all experiences and special gratitude for the hits.

Gratitude, as an element of character, is also at the root of providing praise and recognition to others. Saying “Thank you” or “I appreciate you and your hard work” originates from this element; it requires selflessness but showing honest gratitude to your people and your team will propel them to new heights. Leaders who demonstrate gratitude are more personally grounded and are often better able to connect with and build relationships with team members.

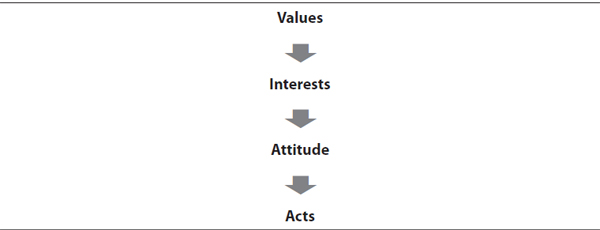

Visualize an iceberg. Beneath the water’s surface is the larger volume of ice, which constitutes your character (Exhibit 3.2). Above the water’s surface, the smaller volume of ice represents your values. Your character is always evidenced through your values, and, as a leader, you must consciously appreciate the interplay between character and values. To value something is to place importance on it, to show genuine interest in it. If you value money, for example, you are interested in money. You tend to read about money, talk about money, look for ways to earn money, save it, spend it, and invest it. And what you display interest in you have a favorable attitude toward. This attitude moves you to act in ways that move you toward the pleasures you have learned to associate with your values. Because you value some things more than others, you are therefore more motivated to seek the pleasures associated with some values more than others.

There are two types of values: ultimate and immediate. Ask yourself, “What do I value most?” You might answer, “Love, security, independence.” These are ultimate values because they represent what you ultimately desire. On the other hand, if you answered, “I want money and family,” these are more immediate values, and you need to probe further: “What will money do for me?” or “What’s the importance of family in your life?”

EXHIBIT 3.2: YOUR CHARACTER AND YOUR VALUES

To achieve greater levels of maturity and success, you must, as a leader:

1. Recognize the difference between immediate and ultimate values.

2. Understand your own hierarchy of values.

3. Understand where your own hierarchy of values may deviate from or align with the elements of character.

4. Set goals for sustaining your strengths and improving development needs that are aligned with only ultimate values that support the elements of character.

This is no easy task; however, the journey you take to strengthen your inner core can be one of the most rewarding ones of your life because it will show you the signs for unlocking and unleashing your massive potential. It is the path to better understanding yourself and others. It is the foundation for teaching and empowering others to become continuously more capable, committed, and connected. You just have to commit to taking that journey.

In examining your values, you need to distinguish between immediate and ultimate values. A quick way to differentiate is by asking, “Is this all there is?” If you are asking this question, it is likely that you are not connecting your goals with the pursuit of your ultimate values. Here is a list of ultimate values that are measured by the Hogan Motives, Values, and Interest Survey:

• Aesthetics: Art, literature, culture, imagination

• Affiliation: Social interactions

• Altruism: Desire to serve others, to improve everything

• Commercial: Earning money, realizing profits

• Hedonism: Desire for fun, excitement, variety

• Power: Desire for achievement, competition, getting ahead

• Recognition: Desire to be known, visible, self-display, famous

• Scientific: Analytical, new ideas, technology

• Security: Structure, predictability, prudence

• Tradition: Appropriate social behavior, morality, high standards

All 10 of these values evoke pleasure in some way, shape, or form. It is imperative that you ask yourself, “Which ones do I value more?” “Which ones do I value less?” Rank these values in order of importance from 1 to 10, with 1 being the most valued and 10 the least. You need to recognize that this hierarchy controls every decision you make as a leader and ultimately will determine the degree of pleasure or pain you experience as a result of the decisions you make.

Your values and character always play out through your personality traits and leadership style. We will see these connections directly in forthcoming chapters as we explore the Leadership Maturity Map™ and Mattone Leadership Enneagram Inventory. For example, some leaders possess a predominant Helper trait. If this is you, you tend to predominantly value affiliation, security, and altruism, as opposed to leaders who possess a predominant Driver trait and who tend to predominantly value things such as power, recognition, and commerce. Are leaders who possess different predominant traits truly different leaders? Of course they are! They possess different values, beliefs, emotions, behaviors, and skills, and they probably have different automobiles.

Although your value system will propel you in concrete directions that you tend to associate with pleasure, in fact, your past experiences (i.e., reference reservoirs) have taught you which values are the most pleasurable. Leaders who possess a predominant Driver trait, for example, have learned from their references that taking risks, taking control, and being independent have historically yielded pleasure. Because these values are associated with receiving pleasure, they have helped shape every decision they have made. These values will continue to shape whom they establish relationships with and how those relationships will develop. It also causes them to be uncomfortable in situations where they are unable to pursue the pleasure their values possess. Put a leader with an immature predominant Driver trait in a situation where they are unable to Drive, and the results are not good!

Once you, as a leader or emerging leader, isolate your individual values, you can now better understand why you act and behave as you do. When you start exploring your own unique value hierarchy and assess the degree to which that hierarchy either supports or deviates from the elements of character, you make it easier to see why you sometimes make a bad decision, can’t make a decision, or even why your decision sometimes creates conflict. Consider this: If your number one value is security and your second value is power, you have conflicting values so close in rank that you are very likely to experience a lot of stress when making any decision.

When you do make a decision, you measure and weigh the relative probabilities that the decision will deliver either pleasure or pain. For example, suppose I ask you to go into a batting cage and try to hit baseballs thrown to you at 90 miles per hour. If the number one state that you are trying to avoid was fear, you probably would not go into the cage. But if your fear of rejection is stronger and you thought others would criticize you for not going into the cage, you would likely be more motivated to go in and face 90-mile-per-hour fastballs.

In other words, in addition to your values driving you to act in particular ways, the pleasure-to-pain ratio that you perceive and associate with experiences is also at work. Whatever pain you associate with getting into the batting cage, or with making a tough decision, or with implementing a new risky change immediately creates a variety of complex emotional states that can be counterproductive (i.e., avoiding making the decision, abdicating responsibility, etc.). However, if the perceived pleasure you associate with the same action is stronger and more powerful than the pain, you will be motivated to take action.

But which decision is correct? Clearly, if you possess a strong inner and outer core, you increase the probability that you will make the right decision. That said, however, here are some examples of emotional states that leaders try to avoid:

• Fear

• Anxiety

• Guilt

• Worry

• Sadness

• Anger

• Depression

• Loneliness

All of these states are associated with pain, but which ones are the most painful? Leaders must honestly self-reflect and rank these eight states in order of those they most want to avoid in order to learn more about how they make decisions. Assign a 1 for the states you most want to avoid and an 8 for those you find more tolerable. It is very powerful when leaders admit that the number one state they most want to avoid, for example, is fear and they then make the connection to why they are avoiding certain uncomfortable people and situations.

For you to achieve greater levels of leadership maturity as a result of continually strengthening both your inner and outer cores, you must also set development goals and create specific, targeted strategies for strengthening your unique strengths and gifts, as well as strategies for improving those development needs that are aligned with the ultimate values supporting the elements of character. You must also recognize how the values to which you assign either high or low priorities are not the result of intelligent choices as much as the result of experiences, references, and values that have conditioned you within a clearly defined complex network of pain and pleasure.

In the remaining chapters, I will introduce the Leadership Maturity Map and Enneagram in much greater detail. By using these powerful tools, you will be able to recognize your own personal leadership styles, as well as pinpoint the degree of maturity/immaturity you exhibit within your predominant trait and the traits defining your unique leadership fingerprint. As you read and think about these tools, you will also gain tremendous insight into others—your manager, peers, employees, and other important stakeholders—and learn new strategies for working with and empowering them. Clearly, as you strengthen your insights into others and develop powerful strategies for connecting with and empowering others, you will become infinitely more effective, influential, powerful, and successful.

You determine the extent to which your values hierarchy supports or in fact deviates from the elements of character. The following is a list of ultimate values along with their associated ideal priority level to which you should strive:

• Altruistic (very high priority)

• Aesthetics (low to medium priority)

• Affiliation (high priority)

• Commercial (medium priority)

• Hedonism (medium priority)

• Power (medium priority)

• Recognition (medium priority)

• Scientific (low to medium priority)

• Security (medium priority)

• Tradition (medium to high priority)

Ultimately, you must establish goals that clearly leverage your strengths (i.e., behaviors and skills that must be sustained in support of ultimate values that demonstrate character) and address your development needs (i.e., changing behaviors and skills to better support ultimate values that demonstrate character). To make true breakthrough changes that endure, you must:

1. Visualize in vivid detail new positively charged references that result from the positive execution of new behaviors/skills.

2. Associate (and really connect) the new positively charged references, as seen in your mind’s eye, with generating a stronger pleasure-to-pain ratio than the pleasure-to-pain ratio you currently associate with the positively charged references resulting from your past or present behavior/skills. (Note: Feedback from external stakeholders may be helpful.)

3. Use only positive thinking and a sense of optimism.

4. Take action, sometimes little steps first, where you can generate momentum and start to associate pleasure with those little steps.

5. Remove obstacles and impediments to your achieving progress.

6. Work with key stakeholders, such as your manager, peers, and employees, showing humility and an uncompromising desire to improve by asking for their help, support, and ongoing feedback as you make the changes you need to make.

As you move through these steps, remember that real, lasting positive change is based on positive behavioral change but that, as explained, the process begins by your looking within yourself and making a commitment to strengthening your inner core. If you work hard every day—passionately and diligently taking the necessary steps to build a strong self-concept, character, belief system, references, values—your strengthened inner core will drive positive thoughts (e.g., “I can,” “I will,” “I must,” “I am worthy of success,” etc.). In turn, your positive thoughts will drive positive emotions, such as happiness, anticipation, excitement, exhilaration, and empowerment—the emotions that activate and incite positive action.

You cannot experience any emotion without first experiencing a thought. In your brain, the cognitive element always precedes the emotional element. For example, suppose you were at work, one of your children got sick at school, but, for some reason, nobody could get that message to you. Would you experience the emotion associated with your child getting sick? Of course you wouldn’t, because you were unaware that your child was sick! The event never creates stress, conflict, or concern; only the thought about the event does that. So, if you want to change your emotions, clearly you must first change your thoughts. In turn, positive emotions, because they incite and activate, drive positive behavior, such as constructive problem solving, relationship building, and the like, and, of course, positive behavior drives the execution of the skills and competencies that define the outer core of leadership success.

As discussed, mature leaders are positive thinkers. Immature leaders tend to be negative. Mature leaders believe in their ability to work through the challenges presented by the people and situations in their lives. This confidence would never be possible, however, without the experiences that support the validity of their thoughts. Mature leaders, then, are passionate about creating powerful success references for themselves, their employees, their teams, and their organizations. Mature leaders understand the power of references and experiences in fueling individual and collective beliefs about achieving breakthrough performance. Mature leaders, such as Jeff Bezos and Ann Mulcahy, recognize the powerful combination of continually renewed thought and action and how that combination propels leaders and their teams into an increasingly more mature cycle in which there is no choice but to use positive thoughts and emotions to reignite the cycle again and again.

But what about immature leaders? What about their language? As you might expect, their negatively charged references lead to negative beliefs, which lead to nonsupportive values, which lead to negative thoughts:

• I’m a failure.

• I’m being treated poorly.

• I’m a victim.

• Everyone is controlling my destiny.

• The world owes me.

• I can’t do it.

All of these thoughts are either true or false depending on the leader’s reference reservoir. Regardless of whether they are true or false, leaders who live with these thoughts are severely limiting their performance and potential. Leaders simply should not indulge in negative thinking. Here are three skills you can implement, in the moment, to deter negative thoughts.

Worrying about future events creates anxiety in the present, and stress inoculation is one way to reduce that anxiety and minimize negative thinking. Imagine that a stressful performance review is coming up. Let’s say that in the past, prior to previous reviews, you became worried and upset. Your boss is tough—a fast talker, insensitive, and a poor listener. A technique you can use to manage this situation is to write a message to yourself in advance of the stressful situation. Here’s an example:

Relax. Review your strengths and development needs and attempt to predict what your boss is likely to say. Be aware of discrepancies between what your manager says and what you think. Be prepared to bring these subjects up without emotion. It is possible to disagree agreeably. Rehearse your responses to anticipated feedback. Recognize that you need feedback to grow and that you are no less of a leader for accepting guidance. To discourage feedback is to diminish your right to choose how you want to behave and to lose control that comes with behaving in ways that in fact could be better.

Once you have written the message, read it aloud several times before the actual review happens, without actually memorizing it. The goal of this exercise is to get you to remember and internalize the essence of the written message so you can repeat portions of it at different times during the review without sounding rehearsed. This is a powerful skill-building exercise for executives who want to become more grounded, more knowledgeable, and more persuasive in their interactions.

Another great skill-building technique to stop the experience of recurring negative thoughts is simply to close your eyes and tell yourself, “Stop!” It is incredible how effective this technique is in quieting destructive thoughts. Next, you must replace the one negative thought with a positive one. The unwanted thought will probably return periodically, but if you repeat the procedure, you will increase the time it takes for that negative thought to get back into your head. Here are examples of positive self-affirming statements you can use to minimize the influence of negative thoughts:

• I am good.

• I am confident.

• I am competent.

• I am worthy of success.

• I am respected.

• I am admired.

• I am a kind and sensitive leader.

• I am a major contributor.

• I can handle tough situations and people.

• I can handle anger.

• I can deal with stress.

• I will be the best I can be.

As mentioned, positive thoughts alone cannot propel you to new levels of maturity and success. You must also work hard to turn these thoughts into beliefs by creating positively charged references to support the validity of those thoughts. As slow and frustrating as this is for many leaders, it is important to repeat, rehearse, and memorize the preceding list of self-affirming statements. You, the leader, must also visualize the positive end results associated with your positive thoughts as well as the concrete steps you plan to execute in order to achieve them. Leaders must visualize in vivid detail both the steps they will take and the results they will (not hope to) achieve, describing the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the experience. By exercising this skill, you will begin to make a direct emotional connection to the positive thought; even a vicarious emotional experience such as this is often enough to stimulate positive action.

Simply put, mature leaders are better than immature people at disputing the validity of their negative thoughts. One way you can practice this skill is to require proof to test the validity of your negative thought. Ask for evidence. When mature leaders hear, “I never do anything right,” their immediate counterthought is, “Is that really true?” or “What exactly am I not good at?” These counterquestions help the leader dispute the validity of whatever negative thoughts they are experiencing.

Another way to dispute the validity of negative thoughts is by exploring alternative explanations. The important point is that very little happens to anyone that can be traced to one cause; most positively and negatively charged references have multiple, complex causes. You must self-reflect and analyze this complexity to acknowledge and accept that there are, in fact, multiple causes to the setbacks. Immature leaders often latch onto one cause, and usually it’s the most dire.

A healthy belief system, strong character, supportive values, and positive thoughts all contribute to the development of mature emotions. Mature leaders are fully aware that they control their own emotions; they simply make the decision to be happy, passionate, and hopeful in their work and life. As explained, mature leaders are very good at mentally mapping out the positive emotions that empower them to act in mature ways. For example, if you want to improve your team player skills, you could talk about (and write down) any and all past situations where, because you were not a great team player, negative results were achieved either individually or within the organization. Perhaps you were concerned about overcontrolling the team, or you didn’t want to come across as domineering. Whatever the reason, the point of this exercise is to get you to see the connection: ineffective thoughts = ineffective emotions = ineffective behavior = ineffective results.

• Visualize the details of the situation (i.e., the who, what, when, where, why, and how), as well as the negative results—as painful as this might be.

• Verbalize what you have just visualized.

• Ask yourself follow-up questions, such as, “What did you do to handle the situation?” or, “By submitting to others, did that solve the problem?”

• Verbalize your current feelings and emotions based on the details of what you have expressed.

• Now, work with yourself to internally commit to change.

Once you have mapped out a failure scenario, you need to visualize a situation—even if you have few references to support it—where being a better team player will lead to feelings of excitement, exhilaration, and success. First, visualize offering ideas to the team, solving problems with the team, opening up and listening to alternative views, and enjoying the success that comes with both leading and participating with your team. You must visualize again in vivid detail, as you did in the failure scenario. Again, verbalize what you have visualized; use follow-up questions to envision and verbalize successful steps being executed and great results being achieved. The point of this exercise is to strengthen your brain’s cognitive associations between acting on your developmental goal of improving your team player skills and success, both individual success and collective success for your organization.

In this age of accelerating change and complexity, mature leaders must demonstrate versatility. Versatility is independent of predominant leadership type, although some types, as we will learn when we explore the enneagram, have a stronger predisposition to being versatile. Versatility is the most important of all behavioral tendencies because it also represents a measure of social endorsement. Leaders who have learned how to meet the demands of others in a wide variety of situations will, more often than not, receive support and endorsement from those they have helped. On the other hand, those who have been less resourceful in meeting the varied needs of others will often receive less support and endorsement. To be versatile is to observe and empathize. Great leaders are able to recognize others’ needs and empathize with their emotions. As a result, these great leaders enjoy stronger, more vibrant relationships and higher levels of maturity and success. Versatility is the bridge that connects a leader’s inner-core attributes to their outer-core tactical skills and strategic competencies.

Here are some starting points for building your versatility skills:

• Be pleasant; smile more.

• Remember names.

• Ask questions about others’ interests.

• Listen.

• Support what you hear.

You will notice that these behaviors are basic in concept but amazingly difficult to apply consistently. The theme of great leaders, though, is, “What can I do to make it easier for others to relate to me?” One place to look for an initial answer to this question is in areas of commonality. Versatile leaders search their experiences for whatever ideas or events they might have in common with people they wish to relate to. The more you can find to share, the greater probability will be of effective communication. To the extent that leaders and their bosses, peers, employees, or any others for that matter share more interests, they achieve greater levels of communication. Ironically, the levels of nonverbal communication increase with the rising number of shared interests. Gestures come to take the place of words. And that is how it should be. Nonverbal communication is the simplest, purest form of communication and is often less likely to be misunderstood because it emerges straight from feelings. Uncluttered, uncomplicated, and uncontaminated by thought, nonverbal communication represents the true self.

To reach this level of communication, versatile leaders know that the initial encounters with others necessitate modifying their style and self-monitoring without being phony. What makes this skill so difficult to master—for all leaders—is the inner tension that’s created when they temporarily abandon their own comfortable style to assume one more fitting to the individual or situation. Fortunately, whatever modifications leaders make are temporary. When commonality is achieved, you are able now to gradually return to the ways with which you are most comfortable.

The alternative to style modification is to refuse to make any effort to adjust—to label as wrong or inferior what often is merely different. Labeling is a common practice of immature leaders and is designed to help them avoid the tension associated with having to make changes; it saves them work. Leaders who modify their style begin with a decision to accept others’ styles as legitimate and authentic as their own. The next step is to stretch your style to include the qualities common to those to whom you want to relate better. To be truly versatile, then, is to give more to others than might be expected of you. True versatility and maturity know no limits and are not tied to personality types.