NORTH CONE

CHAPTER V

SKATING AND THE ALPHABET

MR DIXON had been up the fell before breakfast, and brought down the news that the ice on the tarn was bearing properly at last. Mrs Dixon had passed the news on. “Well,” she said, “you’ll be coming to no harm, if you follow Miss Susan.” School trunks had been opened, and skates and boots and knapsacks taken out. Mrs Dixon had made them two packets of sandwiches, given them a couple of oranges apiece, and put a big bottle of milk in Dorothea’s knapsack. “They’ll be bringing milk from Jackson’s, I’ve no doubt, but there’s no call for any to go short.” They rolled up their skates in newspaper and stowed them in the knapsacks for easy carrying.

It was a fine, crisp day after a night of hard frost. There was a clear sky overhead, and as Dick and Dorothea climbed the cart track they could see above the trees every cleft and gully of the distant mountains. The climb to the old barn seemed only half as long as it had been when they had gone up there for the first time. Dorothea felt more like dancing than walking. Every now and then Dick seemed to be on the very point of breaking into a run on the cropped pale grass at the side of the track, and these sudden jerkinesses in his walking showed Dorothea that he, too, was as eager as herself.

“I wonder if they’re at the igloo already,” she said.

“They can’t be,” said Dick. “Not with the red-caps having to row across the lake.”

But as they came up to the barn and caught the first glimpse of Holly Howe they saw that the business of the day had already begun. There was the end of the old whitewashed farm-house showing between the trees. There was that upper window that had once been Mars. But there was something new.

“What’s that they’ve got on the wall?” said Dorothea. “Above the window.”

Dick pulled out his telescope.

“A big black square,” he said. “Up on end. Like a diamond.”

“It’s a signal,” said Dorothea.

“But how are we to know what it means?” said Dick.

There was a hail in the distance, and they saw John, alone, scrambling through the dead bracken on the ridge beyond the tarn. Anybody could see that he was in a hurry as he came to the ice, stamped on it once or twice and then came quickly across, walking and sliding. He had a knapsack on his back and was carrying a big, awkward white parcel. Dick and Dorothea went to meet him as he came racing up the slope.

“How does our signal look from the barn?” he panted. “Can you see what it is?”

He turned and looked back to Holly Howe.

“Not half bad,” he said.

“But what does it mean?” asked Dick.

“We haven’t decided yet,” said John. “Let’s try how it works from this end. I stuck some whitewash on these to make them show against the dark stone. Can I go up?”

“Of course,” said Dorothea.

“Let’s,” said Dick.

They went up the steps and into the loft where Dorothea and Dick had shivered two nights before while sending out their flashes to catch the attention of the Martians. John propped his parcel against the wall, where Dick examined it carefully. It was simply two big flat pieces of wood, one of them a triangle and the other a square.

“Look out!” said John. “The whitewash is only just drying!”

“Have you lost something?” said Dorothea, seeing John looking this way and that about the loft.

“I just want something for a hammer,” said John. He ran down the steps again, and came back with a biggish stone.

“This’ll do,” he said, trying it in his hand, and went to the big window. He stood there on the sill, holding to the wall with his right hand and reaching round it and as high up it as he could with his left. He found a crack between the stones, pushed into it a big nail that he fished out of his pocket, battered it firmly in with his stone hammer, and gave it a last knock from below to make it turn upwards.

“But I won’t be able to reach as high as that,” said Dick, who guessed what he was doing.

“Half a minute,” said John. “You won’t have to.”

Out of his pocket he brought a ball of string, another large nail, some double hooks of thick fencing wire, and a big brass curtain ring.

Dick and Dorothea watched, open-mouthed.

John threaded the string through the curtain ring, reached round the wall to hang it on the nail he had just fixed, pulled the string through until it was long enough to reach the ground outside, dropped the ball after it, picked up the other nail, the hooks and the wooden shapes, and hurried out and down the steps. The other two ran down after him.

He cut off the ball of string and put it in his pocket. Then he fastened one of his hooks to the string, tying the two ends of the string together so that neither end should slip through the ring high up on the end of the barn.

“If it ever comes down,” he said, “don’t either of you try reaching out of that window to put it right again. Wait for Nancy or me.”

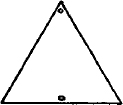

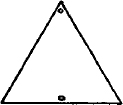

He hung the triangle on the hook by a hole in one of its corners. Then, hand over hand, he hoisted it up until it reached the nail on the wall, where it hung staring white against the dark weather-beaten stones.

“It’ll hang either way,” he said, “pointing up or down. There’s a hole in one of its sides on purpose. And you can make the other one hang either like a square or like a diamond. And the double hooks are so that you can hang one above another. Well, we’ll soon know if it works. Watch Holly Howe.”

“There’s someone at the window,” said Dick, whose telescope was already pointing at Mars. “Red-caps.”

“Nancy and Peggy.”

“The black square’s going!” cried Dorothea.

“They’re hauling it down,” said John. “They’ve seen all right. Yes. I thought so. There comes the triangle!”

A black triangle was climbing slowly up the white wall above the upper window at the end of the farm.

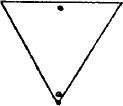

“Now we’ll try the other way.” He hauled his own white triangle down, unhooked it, and hooked it on again by a hole in the middle of one of its sides, so that it hung point downwards.

“South cone,” he said. “When they hoist that in harbour it means a storm from the south.”

“May I pull it up?” said Dick.

“Go ahead!” said John. “Your signal station.”

“Observatory,” said Dick, but he hoisted away all the same, and the triangle had no sooner reached the nail than that other triangle on the wall of Holly Howe shot downwards. A moment later it was climbing again, and this time, it too, was upside down.

“Good work!” said John. “Hullo! Theirs is going down again. They want to start skating. Anyway we’ve done enough for today. All we’ve got to do now is to make a code. Half a minute! I’ll whack another nail in down here, so that you can belay the halyards and leave a signal hoisted, without having to stand by and hang on.”

“Halyards?” said Dick.

“String,” said Dorothea.

A good place was found for a nail, within easy reach of the ground. John drove it in and showed Dick and Dorothea how to fasten their halyards. Two or three times, just for practice, they hoisted square and triangle, and both together. There were no answering signals from Holly Howe, but that, they knew, was because the others were already climbing the hillside.

John explained how the idea had come during the flashings of the night before. “You see, this way, we’ll be able to signal what the plans are for the day even before you know Morse. Nancy said last night you’d got to learn.”

“But what are the signals going to mean?” asked Dick.

“Look here,” said John, “we’ve got four single ones. North cone, with the triangle right way up; south cone, the other way; square, and diamond. And then by hanging two together, one above another, we can make a whole lot more. The main thing is to be able to say what the plans for the day are. We want to be able to hang up something meaning ‘Come to the igloo’ or ‘Come to Holly Howe.’ ”

“Or ‘Come to Mrs Dixon’s,’ ” said Dorothea.

But very little had been done towards making a code when they saw two red-capped explorers leaping through the dead bracken on the other side of the tarn.

“Here they are,” cried Dorothea.

Hurriedly the halyards were belayed, the wooden triangle and square stowed with the hooks in the loft. Hurriedly they picked up their knapsacks and ran down the steps. Already Susan, Titty, and Roger were in sight. There was a distant cheer and the sun glinted on Roger’s skates as he held them high above his head.

“You see,” John was saying as they crossed the ice together, “the whole point of these signals is that once they’re hoisted there’s no need to hang about for an answer. We can start for wherever we’re going, and you’ll know where to come. We can hoist the signals the moment Nancy comes over in the morning, and we can leave them up till we come back. No one will be able to read them except us.”

It certainly sounded as if Dorothea and Dick were considered members of the party. But it was the skating that settled it.

“Jib-booms and bobstays!” shouted Nancy Blackett, violently wrestling with a screw in one of her skates. “Nobody could beat those signals. We could see them as clear as anything, even without the telescope.”

“What about fixing the code?” said John.

NORTH CONE

SOUTH CONE

SQUARE

DIAMOND

“In the igloo,” said Nancy, “when we’re stewing with the dinner. Skating first, anyhow.”

Dorothea had been a little shy of skating with these Arctic explorers who knew all about ships and could signal in half a dozen different ways. She thought they would probably be as much better than Dick and her at skating as they seemed to be at everything else.

She and Dick sat together on some heather at the side of the tarn, fixed their skates on their boots and fastened the straps. She looked round. Everybody else was still busy with the screws. She fumbled with her straps, not wishing to be the first to start. But Dick had never a thought of the others who might be watching. The moment his skates were on he pushed himself off from his clump of heather, rose to standing height as he slid away, and was off. Every day of the holidays he had been with Dot on the indoor skating rink close by the University buildings at home, and this was a trick he had practised again and again, to start off from a sitting position instead of stepping awkwardly about before getting under way.

The Arctic explorers stared, open-mouthed.

“But he can skate,” said Titty.

“Like anything,” said Roger.

“Why didn’t you tell us?” said Nancy. “Of course, you ought to be in the Polar expedition. Not one of us can skate like that.”

“Golly!” said Peggy. “He can do it either way.”

Dorothea was now almost afraid they would think that Dick was showing off. But anybody could see that he had forgotten all about them and was simply skating for himself. He went flying up the little tarn, spun suddenly round and flew backwards, spun round once more, and came flying back to Dorothea.

“Come along, Dot,” he said. “This is lots better than doing it indoors.”

Titty and Roger were skating for the first time. John and Susan had had a little skating at school the winter before. But the Walkers lived mostly in the south, and year after year had gone by with never a patch of ice for them to skate on.

Nancy and Peggy were sturdy, straightforward skaters. Living in the north, at the foot of the great hills, they had had skating every year since they could remember anything, even though the big lake had frozen only once or twice. The smaller lakes and tarns were frozen every year. And at school, too, they had always had a few days when skating took the place of duller games. They could skate, but they knew enough about skating to know that skating was to Dick as natural and easy a thing as sailing their little Amazon was to them.

“You too?” said Nancy to Dorothea. But Dorothea did not hear her. She was already gliding off to join Dick, who had held out his hands to her. They crossed hands and went off together. Left, Right, Left, Right. Dick, in his methodical way, was keeping time aloud as he always did.

“They’re letting us be part of it,” said Dorothea, “because of your skating. Nancy’s just said so.”

“Part of what?” said Dick.

But they were turning now at the end of the tarn where a beck trickled in and warned them to keep their distance in case the ice might be weak near the running water. Nancy was coming to meet them. She was coming at a good pace, with a balancing jerk now and again, for this was her first day on the ice since last year, but anybody could see that she was putting her strength into it. She did not come swooping over the ice like a bird flying. And she knew it very well.

“Hi!” she called out. “You teach me how to twiddle round and go backwards and I’ll teach you signalling. You’ve got to learn anyhow.”

“You just put your weight on one foot and swing yourself round with the other,” said Dick. “At least that’s what it feels like.”

“Like this,” said Nancy, and swung herself round in the bravest manner while going at full speed, coming down with such a bump that if the ice had been a little less thick she must have gone through. But she picked herself up with a laugh. “Not quite like that,” she said. “Let’s have a shot at doing it slowly.”

John and Susan were on the ice now, moving with the earnest care of those who know how easy it is to fall. Roger, who had tried to copy Dick’s start, had sat down three times, quicker than it is possible to say so. He had pushed himself off, sat down, struggled up, sat down, struggled half up once more and come definitely to rest. Titty was standing on her skates but moving just an arm now and again when something happened to make her feel that even standing still was a fairly dangerous adventure.

“What did I do wrong?” Roger asked, sitting where he was. “I bet Susan’s put my skates on crooked.”

“Can I help?” Dorothea asked Titty.

“No. No. No. Don’t touch me,” said Titty. “I’m going to do it by myself.”

And a little later, John and Susan, skating solemnly by, met Titty almost half-way up the tarn, moving on one foot and kicking herself slowly along with the other. Roger was being pulled along by Dick. Peggy and Dorothea were skating together at the far end, while Captain Nancy, glancing rather nervously over her shoulder, was moving jerkily backwards with a fixed smile on her face.

But before long everybody, except Dick and Dorothea, who were already in practice, was more than ready for a rest. Skating uses muscles that seem to be mostly on holiday. There were aches in ankles and shin bones and hurried struggles towards the sides of the tarn where it was possible to ease the pain by sitting down for a minute or two on a clump of heather.

No time was wasted even while they were sitting about. Dick and Dorothea, who had been teaching Arctic explorers how to skate, became pupils once more. Some little flags on sticks had been brought up from Holly Howe and messages were flapped from one side of the tarn to the other, until when it was Roger’s turn he signalled “w-h-a-t-a-b-o-u-t-d-i-n-n-e-r” and Susan said it was high time to go and start the fire in the igloo. Nancy gave Dick and Dorothea their first lesson in flag-flapping and showed them how to make a short flap for a dot and a long sweep from side to side for a dash.

“But it’s no use until you know Morse,” she said. “You’ve simply got to learn it at once.”

“We will,” said Dorothea.

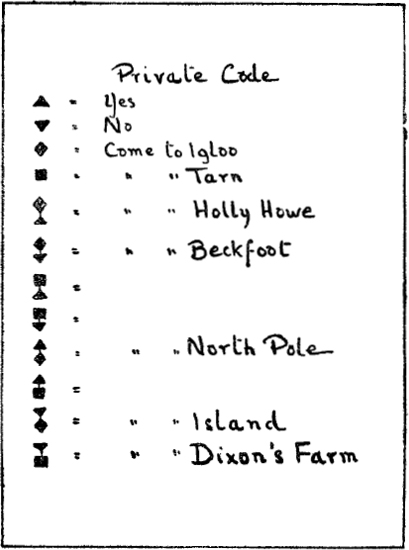

They took off their skates and went up the wood to the igloo for dinner, and while Susan and Peggy were dealing with the fire and boiling water for tea, Nancy wrote out the Morse alphabet for them twice over, once on the last page of one of the tiny note-books in which Dorothea was accustomed to write her romances, and once in Dick’s private pocket-book of scientific notes. Meanwhile, John was working away on the back of an envelope and had found that the two shapes, the square and the triangle, each of which could be hung up in two positions and either separately or together, made it possible to send twelve different messages. “We shan’t want more,” he said, “but if we do we can easily make another shape.”

It was agreed that the most likely signals were “Come to the igloo” and “Come to the tarn.” These were to be the diamond and the square. Then somebody suggested that there ought to be a “Yes” and a “No,” and it was decided that these had better be the north cone or cheerful triangle, looking up, and the south cone or melancholy triangle, looking down. Then diamond over north cone was to mean “Holly Howe.” Diamond over south cone was to mean “Beckfoot.”

PRIVATE CODE. FROM DICK’S POCKET-BOOK

“Same thing as Holly Howe really,” said Nancy, “because we’d be rowing over to Holly Howe to fetch you.”

“But it might mean bringing different luggage,” said Susan.

“Gear,” said Titty.

Everybody agreed at once that a north cone on the top of a diamond was the best signal to mean “North Pole.”

“But how are we to know where it is?” asked Dick.

“We don’t,” said John, “except that it’s at the head of the lake. Nancy and Peggy know, of course, but that can’t be helped. But we’ve never been up there at all. We’ve got to find it.”

South cone over diamond and south cone over square were clearly the right signals for the island and for Dixon’s Farm, because both of these were towards the southern end of the lake.

“The signal for the day goes up first thing in the morning,” said John, “and whoever sees it hoists the same one, so that there can be no mistake.”

“That leaves three signals not settled,” said Dick, who had also been working out the possible combinations of squares and diamonds and north and south cones.

“Something’s sure to turn up for them,” said Nancy. “Anyhow, these’ll be jolly useful, because you can read them right away.”

“Before we’ve done any of our homework,” said Dorothea, looking doubtfully at all the dots and dashes of the Morse code and wondering how long it would take her to learn them.

After dinner they went to the tarn and skated again, and then, late in the afternoon, Nancy called another signal practice. Dick and Nancy went up to the observatory, while John and Dorothea climbed the bracken ridge on the farther side of the tarn. The others rested their shins and ankles but would not leave the ice.

With much looking up of the alphabet and prompting from their teachers, who now and then had to take the flags themselves and explain the muddle by some hurried, skilful flapping of their own, Dorothea and Dick sent their first slow messages to each other, such messages as “Sit down,” or “Stand up,” when it was easy to see at once whether the message had been understood.

At last John took the flag and signalled “Enough,” and Nancy was just picking up her skates to go down from the loft and back to the tarn, when Dick asked a question that had long been in his mind.

SEMAPHORE CODE DRAWN BY NANCY IN DICK’S POCKET-BOOK

“What were those other signals you were doing on the island?” he asked. “Signals without any flapping at all.”

“Scarecrow signalling,” said Nancy. “Semaphore. Tons better in some ways, but more people know Morse. Come on. Where’s that book of yours? You’d better have it down. Hang, I’ve left my pencil in the igloo.”

“I’ve got a fountain pen,” said Dick.

“Let’s have it,” said Nancy, and Dick gave her pocket-book and pen together. She plumped down on the floor of the loft, scribbled down the letters of the alphabet, and over each letter drew a figure showing how flags should be held to signal that particular letter.

“I’ve shoved a face in once, just to remind you which way you’re supposed to be looking when you make the signal. If you get that wrong, everything else is wrong, too.”

Dick watched with interest.

“Which matters most?” he said. “This or Morse?”

“You ought to know both,” she said. “You can’t mix them up because one is dots and dashes and moving about all the time, and in the other each letter stays still while you make it, or at least you stay still while you’re making a letter.”

“We’ll do it,” said Dick, “but it’ll take some time. That’s two whole codes and the signals between here and Holly Howe.”

“Those don’t count,” said Nancy. “They just hang and you can be as slow as you like about looking them up.”

“What about signalling to you?”

Nancy looked out from the loft, across the lake, beyond the islands.

“It’s too far,” she said, “except with lights. You could do it with a lantern. We will some time or other, when you’ve learnt Morse. Anyway, there’s not much point in it because we come to Holly Howe every day and we’ll be signalling from there. But I’ll tell you what,” she went on. “The day we’re all going to the North Pole, I’ll yank a flag up on the Beckfoot promontory so that everybody can see it . . . Over there, beyond the islands, running out into the lake on the far side . . . No . . . farther along . . . Woods behind, at the back of it, then just heather and rock. You can see our old flagstaff near the point.”

ANOTHER PAGE FROM DICK’S POCKET-BOOK

Dick was looking through his telescope.

“Not a very big one,” he said.

“Big enough to hang a flag on,” said Nancy. “Yes. I’ll hang one up to mean ‘Starting for the Pole.’ They can see it from just above Holly Howe and you can see it from here.”

“I’d better write that down,” said Dick, and at the bottom of a page of notes, mostly scientific, he scribbled, “Flag at Beckfoot = Start for Pole.”

“If only the snow would come,” said Nancy, “and give the Arctic half a chance. If it comes quick there might still be a bit of ice round the edges. And anyway, with snow, we can use the sledge. Beastly going to the North Pole over plain grass. Hullo, what’s that brat trying to signal?”

Everybody else was back on the tarn, looking up towards the observatory and beckoning to Nancy and Dick to come down and join them. Roger had got hold of one of the flags, and, standing on the ice, was busily flapping a message. Nancy read the letters out as they came. “L-A-Z-Y-B-O-N-E-S.” “Shiver my timbers,” she said. “What cheek. He means us. Well. Come on. Let’s have one more good go of skating before going home.”

She went racing down the stone steps and away to the tarn to put on her skates, while Roger, his arms whirling like the sails of a windmill by way of helping his legs, was getting himself as far out of reach as the ice would allow. Dick followed her. But there was no more talk of signals that day. Susan thought Titty and Roger had done about enough skating. It was time to go home. And that night there were no lantern signals from Holly Howe or the observatory. The sky was clouded over and the astronomer and his assistant sat in the farm kitchen, trying to learn the Morse code by writing letters to each other in dots and dashes. Softly, at first, as if it hardly meant it, the snow began to fall.