CAPSIZED AND DISMASTED

CHAPTER XXVI

THE NORTH POLE

THE LITTLE SLEDGE, with Dick and Dorothea clinging to it, as flat as they could lie on the top of their sheepskins and knapsacks, flew on in the snowstorm. The larch-pole mast bent and creaked. The sail, full like a balloon, swayed from side to side and the sledge swayed with it. The ropes thrummed. The iron runners roared over the ice.

“We’re going too fast,” said Dorothea.

Dick saw her lips move. “What?” he shouted.

“Too fast,” she shouted back. “A thousand miles an hour.”

“Probably thirty.” Thirty was a good wind speed. He knew that, and the sledge would not be going faster than the wind.

He lifted his head and tried to look back into the blizzard. In a moment his glasses were crusted over with driven snow. He tried to wipe them, but the sledge leapt suddenly as a runner struck some small thing, perhaps a bit of loose ice, or a stone, or perhaps just a crack. The sledge leapt and Dick, holding with only one hand, rolled sideways.

“Don’t let go!” Dorothea almost screamed.

“All right!” shouted Dick, hanging on firmly with both hands again. His glasses would just have to wait. He could see nothing. But how the little sledge was moving.

Dorothea was not blinded like Dick, but she could see very little more than he could. There was the sail, bellying forward and straining almost as if it would burst or lift the sledge into the air. There was the ice shooting by on either side. Snow was lodged in every fold of coat or sheepskin, and was driven, cold and wet, into her mouth whenever she tried to say anything. But on the ice the snow did not rest but blew along and the little sledge blew with it.

“Where are we going?” she shouted, and Dick lifted his head with its two white eyes, huge as his spectacles, though he could not see her through them.

“Straight up the lake . . . Just right.”

“How can you tell?”

“Hills on each side,” shouted Dick. “The wind can’t help blowing straight up. Like blowing through a tube. Peashooter. We’re the pea.”

Dick clung on, blind but happy. Nobody could say this was not sailing. His mast and the sail they had made with the help of Mrs Dixon had really worked. With every minute the wind lasted they were making up for the time lost through starting late.

“Where are we now?” shouted Dorothea.

“Arctic!” shouted Dick.

And suddenly Dorothea knew that she was afraid. Where were they? She could see nothing before, behind, or on either side of the sledge but driving snow. “Arctic!” was all very well. They might be anywhere. Or nowhere. It was as if they had slipped right out of the world into one in which there was nothing but themselves. And they were going on and on, roaring over the ice in this blinding, racing snow. The sledge was white. Dick lay there clinging to it, white all over. He might be looking at her, but instead of his eyes there were only those round white splashes of snow. His hand, the one that had lost its rabbit-skin mitten, was looking wet and blue about the knuckles. She tried, without moving more than she could help, to shelter it for him with a fold of sheepskin. She, too, began to feel cold. It had been hot enough skating along with the sledge, but now, lying on it, being blown along, she felt that the cold was finding its way through everything that was meant to keep it out. Her mind began to run on ahead, but much less pleasantly than usual . . .

Dorothea suddenly shook Dick’s shoulder.

“Let’s stop!’ she cried. “Now! At once!”

Dick scraped at one of his glasses with his bare hand. An eye looked dimly out through the place from which he had smudged the snow away.

“We can’t go back,” he said. “We can’t help coming somewhere if we go on.”

Dorothea shook his shoulder almost angrily. How could she know that Dick was trying to calculate how fast they were moving, and wondering how much he ought to allow for friction on the ice, supposing that the speed of the wind was thirty miles an hour. Besides, he was full of delight at having made his sledge go like John’s. The very last thing he wanted to do was to stop it. Cold? Yes, it was cold, and he did not know where they were, but they were moving in the right direction. Why couldn’t Dorothea lie still? There was nothing to worry about. At least, not yet . . . He tried to get some more of the snow off his spectacles.

And then, suddenly, the sledge tilted sharply upwards, flew into the air, touched something hard, leaped . . . Prickly snow filled his mouth. His hat was gone. The sledge was gone. There was snow in his sleeves. Right up to his elbows. He was down, down, floundering in snow like a dog struggling in water. Something hurt his ear. His spectacles had been torn off his face but still hung from one ear. It was the other that was hurting. He put up his hand to feel it. It was bleeding a little. Scratched by the spectacles probably. Lucky they had not gone altogether . . .

What had happened? Where was the sledge? Where was Dorothea?

“Dot!” he shouted into the driving snow.

“Dick! Dick!”

The answer came from only a few yards away, but he could see nothing but snow, snow driving sideways in the wind, and snow lifted like spray from the crest of a wave and blown onwards and upwards.

“Dot!”

He floundered towards her.

She was standing in the deep snow with her back to the wind.

“Are you all right?” she cried, and almost fell towards him in the snow. “Are you all right?”

She was laughing now, in a shaky kind of way and held firmly to Dick’s arm, as if she were afraid it was going to get away from her. Dick peered at her through his spectacles on which the snow was already settling again.

“Dot!” he said in astonishment. “You aren’t crying?”

“It’s mostly snow,” said Dorothea. “But I didn’t know what had happened to you when the sledge turned over and the mast broke . . . ”

“The mast broke?” said Dick. “How do you know?”

“It’s here,” said Dorothea – “at least it was.”

The mast was all but hidden, but there was the sail, already heavy with drift snow, and the little yellow quarantine flag still on its stick, fastened to the masthead.

“The sledge is here, too,” said Dick. “Come on, Dot, before we lose it altogether.”

The sledge, upside down, was covered with snow, but though several of the ropes had broken when the mast broke, one of the shrouds still held, so that the sledge and the upper part of the mast were anchored to each other. With a good deal of tugging and pushing, while the snow blew down their necks and up their sleeves and blinded Dick again and again by covering his spectacles, they dragged the sledge clear and turned it the right way up. They had lost much less than might have been expected, because of the sheepskins that had been on the top of their baggage. Dick’s skates, pushed in underneath, were still there, and the lantern, fortunately, came up out of the snow still tied to the strap of a knapsack.

One of the knapsacks was gone, the one with the food. It must have been quite close to them, but they could not find it, though in feeling for it Dick found his rabbit-skin hat. He shook the snow out of the hat, crammed it down on his head, and turned to go on with the work of squashing the sail into manageable size, and lashing it down with the broken mast on the top of as much of the baggage as was still on the sledge. If that knapsack was lost it was lost. There was no time to waste.

CAPSIZED AND DISMASTED

“What are we going to do?” said Dorothea.

“We must be right at the head of the lake,” said Dick doubtfully. “The others must be close to us if only we could see. Peggy said the North Pole wasn’t very far from the shore.”

“I wish Peggy was here,” said Dot.

“She wouldn’t know any better than us which way to go in this,” said Dick.

“We must go somewhere,” said Dorothea. “It’s getting worse every minute.”

Suddenly, in all that flurry of driving snow, while Dorothea was growing colder and colder and hopelessly wishing the snow would stop, if only for a few seconds, long enough to let them see where they were, she felt that something had changed in Dick. He had made up his mind what to do, and was burrowing under the frozen sheepskins at the front end of the sledge.

“What do you want?”

“The Alpine rope,” said Dick. He pulled out that great awkward coil of old clothes-line which had seemed so poor a substitute for the real climbing-rope belonging to the rest of the expedition.

“It isn’t strong enough,” said Dorothea. She was dreadfully disappointed. She had thought at first that he had a real idea, and it seemed he was only thinking of mending the rigging.

“It isn’t very strong,” said Dick, “but it’ll do. Hadn’t you better get your skates off ?” It was not of the rigging that he was thinking.

He unfastened the coil and laid it on the top of the sledge, tying one end of the clothes-line to the broken mast.

“So that we can explore without losing each other,” he said. “Come on. You take the other side of the sledge.”

“But where are we going?” asked Dorothea.

“North for a bit,” said Dick, “the way the snow is driving. And then I’ll feel out first on one side and then on the other, at the end of the rope, so that I’ll be able to get back to the sledge each time. The others must be somewhere quite near.”

“What about shouting?”

“We could try.”

They shouted “Hullo!” both together, three or four times and as loud as they could. But it was like shouting in thick cotton-wool. They could not believe anyone could hear them through all that snow. There was no answer at all.

“Let’s get it moving,” said Dick.

The snow was settling thickly over their sledge. They lugged it forward, foot by foot, steering by the way the snowflakes were blowing.

“Anyhow, if we go far enough we’ll come to a road, won’t we?” said Dorothea.

Dick said nothing. The first dozen yards of floundering with the sledge through the drifted snow had been enough to show him that they would stand a poor chance if they had to count on reaching that road that ran round the head of the lake on the other side of the Polar region.

They struggled on another dozen yards, another twenty, by which time Dorothea felt that if they had to go far like this there would be nothing for it but abandoning the sledge. That would be failure of the most dreadful kind. Already they had lost their food. Already they had let the main expedition reach the Pole before them. And now, to have reached the head of the lake, to have crossed the Polar ice, only to struggle to the nearest road without ever seeing the Pole itself, to crawl home without even their sledge . . . it was worse than mere failure. And she had been so sure that Dick would somehow manage . . . She had so clearly seen the others clapping him on the back, and heard Nancy’s loud, cheerful voice telling him he was fit to be a pirate, or something like that . . .

But, even if they abandoned the sledge, and, with nothing to carry, forced their way on, could they count on getting through to that road along which they had driven with the doctor when he brought them back from Beckfoot on the day that Nancy had begun her mumps?

Dorothea knew in her heart that they could not.

“You hang on here,” said Dick. “I’m going to take the rope and explore as far as it’ll let me. I can’t get lost.”

“Don’t let go of it,” said Dorothea, who felt that they were lost already.

“You give it a jerk and I’ll jerk back,” said Dick. “Like divers. But don’t jerk too hard. It’s not very strong for an Alpine rope.”

He took the coil and, trying to shield his spectacles from the snow, floundered off to the right and in a moment was gone, swallowed up in driving snow.

In spite of knowing that he was only a few yards away, Dorothea jerked at the line.

Two jerks came back in answer; and a moment later there was Dick, frantically wiping at his spectacles, struggling back to her out of the storm.

“Oh, I didn’t mean to bring you back,” said Dorothea.

“I thought perhaps you’d seen something,” said Dick.

He set off again, only, instead of going back the way he had come, he bore away to the left. It had felt hopeless and empty away there to the right and, though this was most unscientific, he felt he would like to try the other way first.

He had hardly disappeared in the snowstorm before Dorothea wanted desperately to feel that he was still there at the end of the rope. But she did not let herself give a jerk to it. Two minutes went by. Three. Perhaps more. The rope gave a jerk, seemingly by itself, flicking scraps of frozen snow into the air. Dick was moving slowly round at the end of it. Dorothea put her hand on the rope, just to feel that she was not alone. Suddenly she felt a tug, another, then three or four tugs together. She heard a shout.

Dick struggled back into sight. He had left the rope lying in the snow, to be a guide to them, and was floundering back to the sledge, feeling for the rope where the snow had covered it, but being careful not to pull it with him.

“There’s a house,” he panted. “I could just see it. Come on.”

They set out once more, wading through the snow, dragging the sledge, picking up the rope as they went and using it as a guide.

“Are you sure you saw it?” said Dorothea, as they came to the end of the rope; and Dick stood there, with the end in his hand, looking about him but seeing nothing at all but flying snowflakes.

“I know I saw it,” said Dick; and at that moment there was a lull in the wind, the snow fell less thickly and, not a dozen yards away, and a little above them, they both saw the dim grey shape of a small building. They struggled towards it. Each step was now more difficult than the last. The sledge-runners sank deep into the snow, and their own feet went down and down as if there was nothing firm for foot to stand on.

The grey shape of the building disappeared, just for a moment, in a sudden flurry of snow, and then stood out close above them. It was smaller than Dick had thought when first he saw that there was something before him other than the snow. It was queerly shaped and could hardly be described as a house. The end of it that was nearest to them seemed to be nearly all glass, like a bow window, a big bow window, with snow crusted on the panes. It was only one storey high. There was a little chimney at the back. Its roof was thick with snow, and above the roof a tall flagstaff stuck forlornly up into the storm.

THROUGH THE SNOW

A snowdrift was forming round the front of it. The last few yards would have been the worst if the building had not been there to give them fresh hope. Dorothea leant thankfully against the wall under the windows. Dick left her there and forced his way on. It could not be all windows. He found steps and a door. He hammered on it. There was no answer. He turned the handle, the door opened inwards, and he almost fell through it into a small room.

Just over a hundred years ago, the little place had been built as a shelter from which, in all weathers and at all seasons of the year, the old man who had built it could look out on the changing scenery of the lake and its enclosing hills. He could sit there watching the lake in storm and be himself most comfortable behind windows that could be thrown open in the heat of summer, and with a fireplace so that he need fear no cold in winter. For nearly a hundred years he had been dead, but the old view-house, as it was still called, had never been allowed to fall into ruin. This was the building into which Dick had stumbled. He, of course, knew nothing of its history. It was shelter, and that was all he wanted for the moment.

“Dot!” he shouted, and a moment later the two of them were under cover. They closed the door upon the storm, and stood there panting after their struggle.

“But Dick, Dick, look at that!” cried Dorothea.

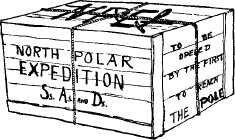

“Half a minute,” said Dick. He was busy wiping his spectacles, which were again covered with snow. He stood blinking, seeing almost nothing. Dorothea was pointing at an enormous box. Dick put on his spectacles and looked.

A queer place it was that they were in. First of all, though there were wooden benches with panelled backs along the walls and round under the windows and on either side of the little fireplace, there was a six-sided seat in the middle of the room, built round the base of the flagstaff they had seen sticking up above the roof, like those seats that are sometimes built round old trees in parks. Then there was a fire already laid, waiting only a match from the box lying handy. There was a small dirty sack that looked as if it must have coal in it. There was a kettle full of water, frozen solid, standing on the hearth. And then, between the flagstaff and the fireplace, there was an enormous box, a great packing-case, roughly roped as if for a journey. On the top of it was written in huge black letters,

“N.P.E.”

Dick had no time to wonder what they meant, for he read on the side of the box nearest to the door:

“NORTH POLAR EXPEDITION

S.’s, A.’s, and D.’s”

and then on the end of it by the flagstaff:

“TO BE OPENED BY THE FIRST TO REACH THE POLE.”

“The Pole must be somewhere quite close to,” said Dorothea. “Captain Flint must have put it here on purpose. But why haven’t they opened it?”

“He’s left a hammer and a wedge all ready,” said Dick.

“But where are the others?” said Dorothea.

“Perhaps we ought to go on,” said Dick. “I could try round again with the rope.”

“Let’s get warm first,” said Dorothea.

But at that moment they both noticed a sheet of paper fastened rather high up on the flagstaff that seemed to grow out of the floor and went up through the roof. Dick knelt on the seat and read aloud from the big printed letters.

“NORTH POLE.”

“Dot!” he shouted, slapping the flagstaff with his hand. “This is it! This is the place they meant. This is the Pole itself. That’s why the box is here. I knew the wind must be blowing us just right. We’ve done it. We’ve got there. And we aren’t last after all . . . ”

AT THE POLE

“But where are the others?” said Dorothea. “They can’t have been and gone.”

“We may have sailed past them,” said Dick. “I wonder if there is any string on that flagstaff ?”

He slipped down from the seat and opened the door. The little room was instantly full of wind, and a small whirlwind of snow danced round the floor.

“Shut it quick!” cried Dorothea. “Don’t go out!” But though, when it was a question of making up stories, Dorothea was better than anybody, in actually doing things Dick often remembered what Dorothea might have forgotten. Once he was busy with an idea, nothing would stop him. They had reached the Pole. They had reached it first. Where was that quarantine flag?

He fell down the steps into the snow, but picked himself up again. The sledge was nearly snowed under, but he knew just where to find the end of the broken mast, with the bits of shrouds dangling from it, and the little yellow flag. Those few minutes out of the wind had brought some life back even to the hand that had lost its mitten. He found the little flag and freed the loop and toggle from the stick. He worked his way along the side of the hut. Better even than he had hoped. There, close by one of the windows, white halyards, new and stiff, came down from the top of the flagstaff and were fastened loosely round a cleat. Captain Flint had known that the discovery of the North Pole would be nothing without the hoisting of a flag. With cold, clumsy fingers, Dick dusted the snow from the scrap of yellow silk, fastened it to the halyards, and was just hauling it up when Dorothea, who had hated even those few minutes of being alone in the hut, came out into the snow to look for him.

The little yellow flag fluttered as if it would blow to pieces as it climbed up, up in the snowstorm to the very top of the flagstaff when, with knots that neither Captain Nancy nor Captain John would have approved, Dick made the halyards fast.

Something trembled in Dorothea’s throat as she looked up and saw that scrap of pale yellow fluttering among the flying snowflakes. How was it that Dick, who seemed so absentminded, could think of things like that?

“Dick, how lovely!” she cried.

“What?” shouted Dick.

“The flag!” she shouted, close to his ear.

Dick scraped almost hopelessly at the snow caked on his spectacles.

“Of course we had to have it up,” he said, and turned to unload the sledge. “Come on, Dot. We’ve got here. We’ll have to wait for the others. Let’s get the things in.”

Between them they carried their gear into the hut, their sheepskins (shaking off as much snow as they could on the way), the knapsack that had the star-book in it, their skates, and the clothes-line that had been so useful. Somewhere in the deep snow at the edge of the ice they had lost the knapsack with the food. Dick was without one of his rabbit-skin mittens. The mast was smashed. There could be no sailing on the return journey even if the wind were to change. But the main thing was that they had found shelter and the Pole. Nothing else mattered.

They leaned their sledge upright against the wall, and for the last time floundered up the steps and into the hut. For a moment they had trouble with the door. Snow had blown between the door and the doorpost. In bringing in their gear they had stamped cakes of snow on the floor. More snow kept blowing in nearly as fast as they cleared it out. But they got the door closed in the end, and stood there, smiling at each other from simple pleasure at being out of the wind, at being able to stand upright without having to crouch to lessen the weight of the storm, at being able to look whichever way they wanted without fear of the blinding snow driving cold into their faces.

“I know what’s happened,” said Dorothea. “You know when all the Eskimos rushed to the shore to get out of the way of the snowstorm? Susan saw it coming, and she wouldn’t want Titty and Roger to get caught in it. She probably saw it long before we did, and took shelter in the woods on shore. And we just blew past them when we were sailing and couldn’t see anything. They’ll be coming along the moment it stops, and we’d better get things ready.”

Dick was considering the great, corded packing-case.

“To be opened by the first to reach the Pole,” he read aloud. “I wish my fingers weren’t so cold.” He squeezed them together and blew on them. Rubbing them was much too painful. But something had to be done about those knots. He had known John and Titty long enough to know that it would never do for them to come along and find that a member of a Polar expedition had used a knife to cut good ropes.

“I’m going to light the fire,” said Dorothea with decision. “They’ll be even colder than we are, waiting about like that.”