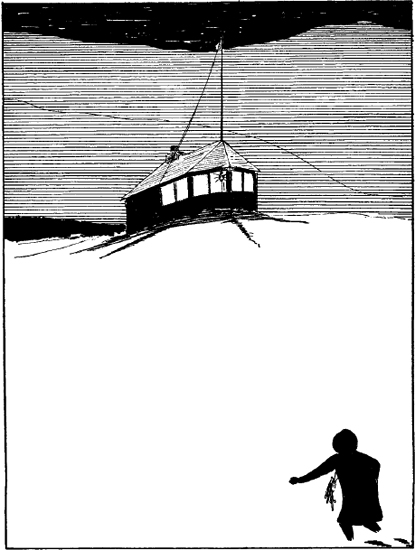

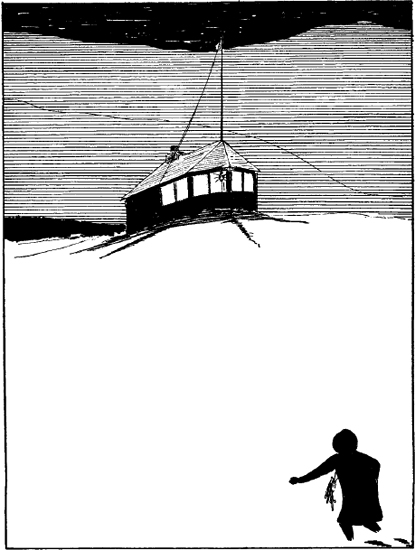

NANCY REACHING THE POLE

CHAPTER XXVIII

ARCTIC NIGHT

HOUR AFTER HOUR had gone by. The short winter day was ending. Dorothea and Dick were still alone at the Pole. And still, outside, great gusts of wind filled the air with flying snow. Inside, the little hut looked very different from the bleak place it had been when Dick first stumbled into it. A cheerful fire was blazing in the grate under a simmering kettle. Dick had spent the afternoon in melting snow (dipped from below the window), so that there should be plenty of water when the others should arive. The big saucepan, that had been the first thing taken out of the packing-case, was standing on the hearth, full to the brim. Dorothea had unpacked the case and arranged its contents along one of the benches, food enough to last a dozen people for a whole day: two cold chickens and a Christmas pudding and what not, with plates, knives, forks, spoons, and mugs. She had counted these at once, and found that there were nine of everything. That meant that Nancy was coming too, and Captain Flint, who certainly deserved to, Dorothea thought, after making such careful preparations. The packing-case itself had been turned over to make a table, and one corner of the hut looked almost like a larder. Dorothea thought that even Susan would think that her Polar housekeeping was not half bad.

At first, thinking that the storm would soon be over, when the main body of the expedition would be coming along, she had been very unwilling to break into the stores of food. But Dick had been hungry, and so had she, and in the end, encouraged by what had been written on the outside of the packing-case, they had made themselves some tea, opened a tin of condensed milk and one of meat paste, taken a few biscuits to eat it with, and given themselves an allowance of two Swiss buns apiece (afterwards increased to four).

“It’s not snowing like it was,” said Dick at last, late in the afternoon, “and not blowing so hard either.”

“They’ll be coming the moment they can see to move,” said Dorothea, “and they may be quite close to us already.”

But the last half-hour of daylight passed, and the dark closed down over the little hut. They had lit the lantern some time before.

The noise of the wind had stopped, and Dick opened a window to look out into the darkness.

“They’ll be coming soon now,” he said. “It’s stopped snowing. Let’s hang the lantern in a good place.”

No one had ever thought of using the viewhouse at night, so there was no place to hang a lantern, but Dick worked one of the nails out of the lid of the packing-case and hammered it into a crack in the Pole as high as he could reach.

“It’ll show through all the windows,” he said. “They can’t miss it, wherever they are.”

“Going back in the dark’ll be a good deal easier with all of us together,” said Dorothea, “but we’re going to be dreadfully late.”

She came to the open window with him, and looked out at her own shadow and Dick’s thrown by the lantern on the snow.

“Good,” said Dick suddenly. “Stars. There’s Orion.”

Away to the south stars showed in a patch of clear sky, and among them were the three bright stars of Orion’s Belt. Dick climbed over the window sill and dropped down into the snow.

“Right up to my waist,” he said cheerfully.

“Where are you going?”

“Just to look at the Pole Star,” he said. “Of course, it won’t be really overhead, but still . . . ”

He floundered through the snow round the corner of the hut.

“Come back, Dick,” cried Dorothea. “Come back. Do come back.”

“What is it?” He struggled back under the opened window.

“Nothing really,” said Dorothea, a little ashamed. “But we ought to keep the window shut. It’s no good getting the hut cold again. And there isn’t an awful lot of coal in that sack.”

“You can shut the window,” said Dick. “I’m going round to clear the snow from the door, so that we can open it without getting another lot inside.”

He was gone. She heard him scraping at the door, and presently he came in after shaking the snow off on the top step.

“It was like swimming just by the door,” he said. “Jolly deep, too. Piled right up. And I couldn’t see the Pole Star. All clouds. But it doesn’t matter. Orion’s sword showed clear for a moment, north and south. Anybody could see that the hilt end was pointing straight to us.”

Another half-hour went by. Dorothea made some more tea, and they took two more buns (making six) and some biscuits. Now, at last, they began to think that something must have gone seriously wrong. Where could those others be?

“They’d never give it up,” said Dick.

“Captain Flint may be with them,” said Dorothea. “And Nancy, too. He may have made them start home when the snow stopped.”

“They wouldn’t go,” said Dick. “Not without us.”

“They started first,” said Dorothea, “without waiting for us.”

Dick was silent for a minute or two. He had gone to the window again, and was looking out, where the warmth of the room had melted the snow on the window-panes, at the faraway lights on the shores of the lake.

“Perhaps they think we couldn’t have got so far,” he said. “They didn’t know we had a sail.”

“That’s just it,” said Dorothea. “They wouldn’t mind turning back if they thought we were somewhere behind them.”

Dick turned suddenly from the windows, and glanced up at the lantern and then at the fire that was sending flickering shadows over the walls.

“We’ll show them just where we are,” he said. “Let’s push the box in front of the fire so that the light from it doesn’t show, and then we can signal with the lantern.”

“How?”

“Like we did before. Only this time we can send a real signal.” He pulled out the little book and turned up the page with the Morse code. “All we’ve got to do is to signal n-p – North Pole. They’ll know at once. A long and a short for n. And p’s a short, two longs, and then another short. They’ll know at once, and nobody else will.”

Hopes rose again. Dorothea remembered that successful signalling to Mars.

In a few minutes the light from the fire was screened by the packing-case, and Dick and Dorothea were busy at the windows, taking turns in showing the lantern and then shielding it with a sheepskin. Long, short . . . Short, long, long, short . . . Again and again the signal n-p was flashed into the night.

“With all those windows it’s as good as a lighthouse,” said Dick. “They’re bound to see it if they’re anywhere about.”

Now and then they stopped to see if anywhere in the darkness another lantern was flashing in answer. But there was never a sign that anybody had noticed what they were doing.

At last they tired.

“They must have seen it by now,” said Dick, and hung the lantern once more on its nail.

And then, suddenly, Dorothea made up her mind that they must leave the Pole at once. Time was going on and on. Whatever had happened to the others, they themselves must face that struggle through the snow and the long journey home in the darkness. They must not wait another minute.

“Dick,” she said, looking at that neat larder, “let’s put everything back. We’ve got to start home.”

“But we can’t go away now we’ve signalled,” said Dick. “We’ve told them we’re here. They’ll be coming, and we’d be sure to miss them in the dark.”

This was worse than ever. Dorothea hardly knew what ought to be done. It was not like one of her own stories, in which it was easy to twist things another way or go back a page or two and start again if anything had gone badly. It would not have mattered so much if only they had left a message at Dixon’s Farm to say they might be late. She thought of Mrs Dixon, and Mr Dixon and old Silas, with nightfall long past, and empty places at the kitchen table. Dick never thought of things like that. But what could they do? There they were at the North Pole. The others must be somewhere out in the Arctic night. Signals had been made to them. It was too late now to take the signals back. Dick was right. There was nothing to be done but to wait.

She gave in. She was very tired, and so was Dick. They spread their sheepskins on the floor, used the packing-case to lean against, and sat there watching the fire.

*

“Ahoy!”

Dorothea stirred in her sleep. Time to get up? Had Mrs Dixon found a new way of calling them?

“Ahoy!”

There it was again. A long way off.

Dorothea opened her eyes. Where was she? The fire had burnt low, but she saw the red glow of its embers not far from her feet. With a jerk, she pulled her feet away, and then saw that there was no need. She knew where she was now. That hard thing against her back was Captain Flint’s packing-case. They were at the North Pole. She looked at Dick, huddled down on the sheepskins, with his chin on his chest. Should she wake him? Or had she dreamed that noise? She must put some more coal on the fire. She stirred and then again, not so far away this time, she heard that call.

“Ahoy!”

The lantern was still burning, hanging from the flagstaff in the middle of the hut. The windows looked black except where the light from inside showed the edging of frozen snow outside the glass. It was black night out there, and the lantern made it seem even blacker than it was.

“Ahoy! Ahoy!”

With a soft plop something hit one of the windows and stuck there, a white splash on the blackness.

“Ahoy! Ahoy, there! North Pole, ahoy!”

“Here they are!” cried Dorothea. “Here they are!” She shook Dick by the shoulder. He woke with a start, rubbed his eyes, and then, as he heard Dorothea crying, “Here they are!” and another lump of snow flattened itself against a window, he jumped to his feet and opened the door. A cold breath of night air came into the hut, and the lantern threw a bar of light sideways across the snow.

“Make straight for the door,” Dick shouted. “It was awfully deep, but it’s not bad now.”

“It’s quite deep enough here,” said a clear, cheerful voice out of the darkness. “I’ve been fighting through it for ages. Didn’t you hear me yelling?”

Dick and Dorothea stared out into the night, and at last saw a figure struggling in the snow. A moment later Captain Nancy, with her skates hung round her neck, stumbled up the steps at the door.

“Good! Good!” said Dorothea, eagerly dusting the snow off her.

Just for a moment Nancy felt herself dreadfully tired. Even with all her efforts to get into training she was not yet the sturdy Amazon pirate she had been before she had got the mumps, and had had to spend so long being coddled in a hot bedroom. She sat down on the seat at the foot of the flagstaff.

NANCY REACHING THE POLE

Dick was still looking out into the night.

“But where are the others?” he said. “They haven’t turned back?”

“What others?” said Nancy. “I started the moment I saw your signals. The others are at Holly Howe. But why are you here at all? Everything’s fixed now. We’re all coming tomorrow.”

Dick stared at her.

“But you put up the signal,” he said.

“What signal?” said Nancy.

“Flag on the Beckfoot promontory.”

“Oh, that! To say I could come to the council in the Fram. The blizzard scuppered that. But the others were there all right. Everything’s settled. And now you’re here already . . . ”

Dick was digging furiously into his pocket. Out came a lump of tangled string, a handkerchief, an indiarubber, and with them that important pocket-book. He turned hurriedly back, through sketches of the constellations, drawings of the Nansen sledges, the pages on which Nancy herself had drawn the semaphore alphabet for him, and the Morse code, until he came to the page for which he was looking. There, at the bottom of some mixed notes, he found what he wanted, and held it out for her to see.

“Flag on Beckfoot=start for Pole.”

“I wrote it down when you told me,” he said, “in the top of the observatory the day we were learning the signals.”

Nancy’s mouth opened. She bit her lower lip. Her indignation was gone.

“Golly,” she said. “I remember your doing it. And something happened, and I never told the others. And then came mumps, and I forgot every little bit about it. And then when Captain Flint asked about my getting away soon enough for the council in the Fram, I said that if I could I’d run up a red flag and the biggest I could find. And so I did. It was a bedspread.”

“I saw it at once,” said Dick, “but I was jolly late anyhow, so I thought the others must have started.”

“And you two came by yourselves and got here through all that blizzard?” said Nancy. “However did you find the Pole?”

“The blizzard helped, really,” said Dorothea.

“We were sailing,” said Dick.

“Jib-booms and bobstays!” cried Nancy. “Sailing? In that?”

“The wind was just right,” said Dick. “It took us straight here.”

“Well,” said Nancy, “it’s the best thing I ever heard. You couldn’t have made it more real. But what a pity you did it a day too soon.”

“And we’ve gone and opened the stores,” said Dorothea. “And eaten some of them. You see, we lost our food when the sledge turned over and the mast broke . . . ”

“Capsized!” cried Nancy. “Mast gone by the board! Oh, you lucky, lucky beasts! Of course, you were right to go for the stores. That’s what they were there for.”

She looked round at the neat larder, read the writing on the packing-case, and looked at the label fastened on the flagstaff.

“He’s really not done it half badly,” she said. “I forgot he’d have fixed up stores for tomorrow. I swiped a cake, just in case you might be starving.” She pulled it out of her knapsack and put it on the bench with the rest of the food. “Have you had supper yet?”

“We haven’t properly,” said Dorothea.

“You’d much better,” said Nancy. “I will, too. How did you manage about water?”

“There was a kettle full to begin with,” said Dick, “and we’ve melted a lot of snow.”

“Good work,” said Nancy. “Let’s have supper right away. Anybody’d say we ought to. It’s no good thinking of starting back now. I can’t, anyway. We’d better not use more coal than we can help.”

She broke up the lid of the packing-case, splitting it in pieces with hammer and chisel. The fire blazed up again when fed with the dry wood. The kettle boiled. Tea was made. And all the time Nancy kept asking one question after another. Nearly a month’s questions were boiling inside her and waiting to be asked. There was the voyage in the blizzard with the sailing sledge, every detail of which she wanted to know. But there was also that business of the cragfast sheep, of which she had only heard at second-hand, and the story of Captain Flint’s finding his houseboat not at all as he had left it.

“Shiver my timbers!” said Captain Nancy, sitting on a sheepskin in front of the fire with a mug of hot tea in one hand and the leg of a chicken in the other. “Shiver my timbers! The others will be jolly sick at missing this.”

“What’ll they do?” asked Dorothea.

“Come along tomorrow,” said Nancy. “Daylight. Fine weather. Captain Flint to help them. I’ve left a message to let him know we’re here. He’ll collect them in the morning and they’ll come along as tame as anything . . . ”

And at that moment there was a chorus of loud “Hurrahs” close outside the hut. At that moment the relief expedition, after struggling up from the shore towards those lighted windows, had noticed the halyards and turned their torches upwards and seen the little yellow quarantine flag that told them their search was ended.

Nancy was up in a flash and had the door open.

The loud “Hurrahs” of the rescuers turned to shouts of astonishment. “It’s Nancy!” “Nancy’s here, too!” “But Captain Flint said you were at Beckfoot!”

“So I was,” said Nancy, “till I saw their flash signals. Proper ones this time. Morse, n-p for North Pole.”

“Lantern signals?” said John. “We never saw them.”

“But why were they here?” said Susan.

“Why didn’t they come to the council?” said Peggy.

Everybody was talking at once. There was Nancy clapping people on the back, shivering timbers, barbecuing billygoats, delighted to be with the others once again. And there were John and Susan, very pleased indeed that the search was over, for they had known that Titty and Roger were too tired to go much farther. And there were Titty and Roger trying to tell the story of their journey. And there were Dick and Dorothea dreadfully anxious to explain that really it had not been their fault that they had started a day too soon. And there was Peggy, tremendously hoping that Captain Nancy would not think she had done so badly, and very pleased indeed that she was back and ready to take command. She herself was quite ready by now to be a mate once more.

Presently Nancy noticed that John, Susan, and Peggy, although they had come to rescue them, had very little to say to the D.’s.

“It’s not their fault at all,” she said. “It’s mine, really.” She explained about the signal. “I’d forgotten all about it, with the mumps coming in between.”

“That’s all right,” said John. “I thought all the time they couldn’t have done it on purpose.”

“Anyway it’s a good thing they’re found,” said Susan. “But I don’t know how we’re going to get back and rested enough to do it again tomorrow. Titty and Roger are about done.”

“So’m I,” said Nancy joyously. “So’s everybody. That’s the best of it. Now you’re here there’s no need to do it again. We’ve done it. We’ve all of us done it. This is miles better than anything we planned . . . Sailing to the Pole in a gale of wind and a snowstorm.”

“Sailing?” said John.

“Rather,” said Nancy. “Sailing . . . and then nobody knowing where anybody was and your tremendous sledge journey in the Arctic night. Why, tomorrow everything would be easy. A picnic. Like going for a walk at school. But this was the real thing. They’d never been farther north than the Amazon and they found the Pole all by themselves.” And then she said things about the D.’s and their wild sail through the blizzard that made Dick splutter out that it was only accident, and Dorothea sparkle with pride in him. First that sheep and then the sailing. They knew now that he was more than a mere astronomer.

“Everybody’s done jolly well,” said Nancy.

“Captain Flint, too,” said Roger, admiring the larder. And then, noticing the coal-sack. “That was why his sledge was all black and sooty.”

And then, of course, the relief expedition, although it had set out after supper, found that after crossing the Arctic to the Pole it could eat a little more. The big Beckfoot sledge was unpacked. Sheepskins and knapsacks were brought in.

“It just can’t be helped,” said Susan. “We’ve got to spend the night here now. I’m sure mother wouldn’t mind. The main thing is that we’re all here.”