Evidence of the great historical styles of the past is all around us. Whoever built your home was working within a tradition – even if at first sight it might seem as though there is nothing special about it. For every house, in every style, belongs to the developing history of architecture. With careful analysis of what you see every day, you can step into the world of architectural history, and begin to appreciate the many beauties of the buildings of our towns and cities.

The first step towards understanding architectural history is to analyse exactly what you see around you. What are the major component parts that your house is made of? What do they look like, and how were they put together?

If your house is built with plain brick or plastered walls, the chances are that you have never given them much thought. And yet these are the most important parts of any home. The purpose of a house from the beginning of time has been to build somewhere that is protected from the elements. The very first houses were shelters created out of whatever material was available. In England, with its dense woodlands, sections of tree trunks were tied together to form a rigid tent, and its surface was covered with woven twigs and leaves. Sometimes walls were built up using mud and clay. Once sturdier materials could be moved from place to place, the first upright masonry walls began to appear.

The wall and the roof are still the most important elements in architecture, and very probably their appearance was the first thing that the builder of your house decided on.

Step outside your home and look carefully at the surface of the outer walls:

• is it made of timber?

• is it made of brick?

• is it covered in plaster, or render?

• is it made from a concrete frame?

The location of your house may well account for the material of the outer face of the walls. It is only comparatively recently in the history of architecture – for most people, less than two hundred years – that it has been economically viable to move heavy building materials around the country. Well into the twentieth century such expensive transportation was still avoided if possible. That means that in most cases the surface of the walls will be made from a material that can be found locally. If you live in a more recent home, you need only look at the fronts of older buildings to get a clear idea of what the local building material is.

Walls built with timber frames are comparatively rare in Britain, although many have survived from hundreds of years ago. Originally, numerous houses were built with timber frames and covered with timber clapboarding, but as brick and stone became increasingly available, and because the priority in a wet country was to keep warm and dry, the timber cladding was often later replaced with brick. On the other hand, when English settlers arrived in the Americas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they found plentiful supplies of timber which could be easily felled and worked. The result was a style of architecture which has remained popular ever since, especially on the east coast of the United States.

Builders traditionally used local building materials, which accounts for the wonderful variety of brick and stone in our houses. This modern house echoes that tradition.

English settlers in the New World used plentiful local timber to build in a way that was familiar from home.

A timber frame with timber cladding is not necessarily inferior to masonry construction. Units can be prefabricated and transferred quickly and cheaply to site, and because of their natural appearance can easily blend in with any other local material. Nowadays, thermal insulation standards can be met with thick layers of mineral wool or other modern materials, and so the protective properties of the external layer are less important than they were traditionally. In fact, the Nordic countries with their plentiful forests make great use of timber-framed, timber-clad structures for modern high-quality housing, and it is likely that their use will spread.

The most solid building materials are found under the earth. In Britain, there is a large selection of stones and clays which have provided a tremendous variety of building materials. In the south-east of the country, around London, the clay is just right for making bricks, and so for many people who have seen the characteristic rows of houses in the capital, England is a country of brick. But there is also a long belt of limestone that stretches across the land from Dorset in the south-west up to Yorkshire in the north-east. This provides the varied and attractive stones that characterize the architecture of much of the centre of the country. There are also coloured sandstones in the west and north-west.

Because the wall is the most important part of any house, builders will have to adapt their work to the natural properties of the material. Brick can be cast into small units. Most limestones can be easily cut and carved into blocks, sometimes into the largest units that can be comfortably manoeuvred into place by a mason working alone. And because the dense granites of the far north and west of the country are so difficult to cut and so inconvenient to move around on a building site, the architecture of those regions is correspondingly plain and massive.

Most kinds of limestone used in building are well suited for decorative carving.

Quarrying and working with stone is always going to be a relatively expensive part of the building process, and yet in many countries the local clay is not suitable for making good quality wind- and rainproof bricks. The solution is to cover a wall with a thick mix of plaster, properly known as render, usually based on gypsum or more commonly lime mixed with other materials including sand or gravel. In some areas, including for example those parts of Scotland where an expensive granite is the local natural building material, one can see a great deal of housing built of cheap bricks or blocks which are protected against the rain by a thick layer of render.

Although a rendered wall is therefore a comparatively cheaper solution, it does have many advantages. It can be painted in cheerful colours, and in some parts of England, especially East Anglia, the surface was often decorated by pressing it when wet with patterned wooden moulds. This is known as pargetting.

Concrete walls – usually, in fact, concrete frames with panels made from other materials – are the result of architectural fashion rather than of natural circumstances. If you live in a building such as a block of flats from the 1950s or 1960s where you can clearly see large amounts of concrete, the chances are that you are daily experiencing the conscious attempt of an architect to get involved with the design experimentation that was going on at the time. In order to understand your building best, you need to stand back and look at the block as a whole, and to try to understand its logic. Chapter 5 of this book will give you an insight into what effects architects at the time were trying to achieve with work of this type.

A building will not keep the rain out without a roof. In a warm climate with little rain a flat roof may well be completely adequate, for water will dry out before it becomes a problem. In northern countries, however, builders and architects have right from the start tried to design roofs that will direct rainwater away from the building as soon as possible. The heavier the rainfall, the steeper the roof, and the deeper the overhang of the roof over the top of the wall.

In these countries, the roofing material too is likely to have been gathered locally. The earliest and most easily available solutions such as thatch were often unsatisfactory in areas where they could never properly dry out. Thus at the time that walls were beginning to be built of permanent materials, so too were roofs. Clay could be baked into roof tiles of different shapes, and once the roofs of London were covered with them. From the end of the eighteenth century they were increasingly replaced by slate from Wales or the north-west and south-west of England – a hard, thin material that easily provided a waterproof layer. In fact slate was also often used to provide a damp-proof course before the invention of more modern materials and methods.

The primary function of the roof is to keep rain out of the house, and to throw it away from the walls.

You know that the materials houses are made from are usually derived from the area they are built in. That is the first stage in understanding the logic of architectural tradition and style.

It is a natural characteristic of mankind to try to impose both order and decoration onto created objects. It is also natural for anyone who works with their hands continually to want to improve and refine the work they are doing. It is because of this that the basic materials and methods of building have evolved all over the world into sophisticated architectural styles.

Simply using the materials to hand in the method best suited for working with them will always provide a certain consistency. With that consistency comes a logical degree of natural variation. Bricks can be made in different colours and with different textures, for example. Some stone, such as the flint found around the south and east of England, is naturally varied in appearance, and it can be cut in different ways or mixed with brick. And clay tiles moulded into different patterns can be used to clad walls. All these add variety to the local architecture of a place without in any way disturbing its consistent character.

Brickwork in England is traditionally laid in either English bond or Flemish bond.

If your house is built of brick, have a look to see how the bricks are laid. In most modern buildings, they are simply laid end to end longways: that is because they are simply forming a skin over the rest of the building structure within. But traditionally they were laid in different ways to ensure a strong bond across a thick wall.

The most common bond is the Flemish bond, in which you can see the long and short ends of the brick (known respectively as the stretchers and the headers) alternately along a single course. An alternative is English bond, which was often used in mediaeval times and was revived by the Victorians: here you will see an entire course of headers followed above by an entire course of stretchers. Some of the bricks could be of a different colour. With possibilities like these, it is easy to create attractive, but logical, variations in the character of different walls in one region.

Walls and roofs are important, but they are of course not the only major features of a building. The other basic elements of a building are described below in the order in which they developed historically.

At first, fires were simply lit in the middle of a room, and the smoke went out through a hole in the ceiling. In time permanent fireplaces were built. In country areas you can sometimes see where a brick chimney was added to an older timber-framed house. By placing a pair of fireplaces back to back within a house, it was possible to have two fireplaces using the same chimney stack. The fireplaces of another pair of rooms on an upper floor could later be incorporated economically. In time, builders and architects could begin to use the prominent form of the chimney as a major element in their design of a house.

Some of the great houses of the Tudor era have magnificent brick chimneys such as these.

The tops of the chimneys could become decorative objects in their own right. Builders of large houses in Tudor times created some beautiful ornamental chimneys.

The obvious way of extending a house cheaply was to use the space up in the roof. In many old houses a floor was simply added in the middle of the space to create two low rooms, and the residents would have used a ladder to move between the two.

In time, however, the ladder developed into a permanent staircase. If there was a solid wall within the house, for example as part of the chimney construction, it could also support the stairs. When houses were built in rows, the staircase was generally located alongside the party wall with the neighbour, because it did not necessarily require natural light in the way that a room does. That may well explain the position of the staircase in your house.

A window on a gable shows that roof space has been exploited for an extra room.

The gable is a familiar symbol of a home, and thus popular with developers.

Building tall roofs to throw off rain meant that there was potentially a great deal of space in the upper part of a house. Most simple houses had a gable at either end of the roof, but by building more of them the owners could increase the headroom in the attic and gain another valuable bedroom. You can look out for this in old buildings that have been added to over the years.

People found gables attractive in their own right, because they gave another opportunity for variety that made sense economically. They also provided more space on the outside of the building for decoration. For some, the distinct shape of a tall gable came to represent their idea of what a home ought to look like. That is why many modern buildings have gables on them, even where they are not perhaps strictly necessary.

We have looked at the massive elements of buildings that give them their basic character. Now it is time to look at those important details of a building which provide a key to developing architectural traditions.

The parts of the building we have looked at so far are permanent and fixed: they were intended by those that created them to remain where they were for hundreds of years. But many other elements of buildings are intended to be flexible in some way. In particular, doors and windows need to open and close. And because they (unlike most parts of the building) are in regular daily use by the occupants, they need to have special characteristics to make them easily identifiable and pleasant to use.

Until very recent times, all doors were made of timber, and both doors and windows had timber frames. Timber is easily worked by hand, and over generations joiners began to perfect the details of their designs. If you look at unaltered older buildings in any one particular area you will see that they largely share the same characteristics. In a Victorian street, for example, you will notice that front doors are similar, and windows are made so that they open in the same way. The ironmongery may be the same from house to house, too. To some extent that is because it was more economical for a builder to use the same pattern over and over again; indeed, identifying common details like this can tell us which houses were built by which builders. But it is just as true that architects and builders felt that these details provided an opportunity for a house to show that it belonged to a family of houses of the same type, which may have been a way of demonstrating the status of a speculative building development to potential customers.

Houses in a Georgian terrace, for example, may share common details such as fanlights and wrought-iron balconies. Anyone approaching them would be able to guess what kind of house they were entering. The quality of the decorative plasterwork inside would also tell visitors about the type of place they were in.

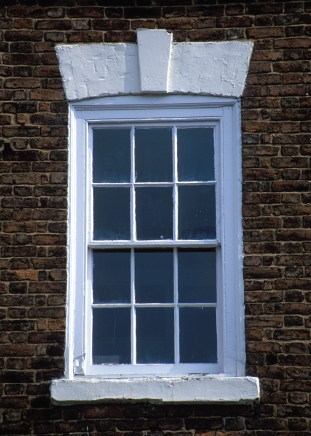

The double-hung vertical sliding sash is an English invention. Counterweights attached to cords can hold the window open in any position.

Casement windows with leaded lights give a feeling of domesticity and comfort.

By inspecting the timber details of a house it is possible to get as good an idea of the style of a building as it is by looking at the major features such as the walls and chimneys.

• solid, plain oak door and window frames with squared edges and simple joints are either very old, or are conscious imitations of mediaeval work.

• painted broad sections of timber, often with simple curved edges, are characteristic of seventeenth-century joinery.

• complex painted sections of timber, sometimes made up by pinning several strips over each other, became common from the late seventeenth century onwards. This type of joinery makes a great deal of use of ‘ogee’ mouldings – strips of timber that are cut into the form of an S.

• varnished or polished (rather than painted) timber became fashionable in early Victorian times. Over the nineteenth century, the standard of joinery became highly sophisticated. Some late Victorian architects were intrigued by the superb quality of Japanese joinery, and tried to imitate it where their budget would allow it.

• plain, minimal timber or metal sections, usually painted, became common for most housing from the 1930s onwards. The reason was not only economy: it was also because architectural fashion was reacting against the complexity of earlier styles.

The front door is an important place to make a statement. It may be the only decorative feature on the street front of a house.

Wrought iron balconies and verandahs became popular during the Regency era.

The design of other timber parts of the house developed in the same way. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century skirting boards in a large house, for example, were characteristically tall and ornamental, whereas more modern houses have very minimal ones. Their purpose is to mask the join between the plastered wall and the floor.

Doors and windows do more than simply function: they also add important interest. Those who design and build houses are always looking out for ways in which they can give a place a special dignity and significance without wasting money. The arrangement and style of the openings is a logical way to do this.

It does not seem to be the case that rooms were historically designed to suit a certain layout of furniture, because up to the end of the eighteenth century most people had very little in the way of moveable belongings. Rooms were seen primarily as flexible open spaces, and were much more important than anything within them. Special attention was therefore given to the position of the door and windows.

The door to a room in an eighteenth-century stately home: decorative joinery at its most magnificent.

In some cases, the door might be in the middle of a room, facing the fireplace: in fact, a fireplace operates best when it is positioned directly opposite a door. This easily gives certain grandeur to any room. There was unlikely to be much choice as to the wall on which the windows would be positioned, but the architect could decide how many there would be, and what their proportions should be. If it was possible to match up the proportions between all the various different openings, so that for example the windows on the upper floors would be exactly three-quarters of the size of the ones downstairs, the result would be likely to look elegant and balanced.

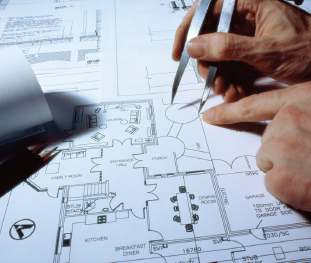

Buildings need to be recorded for several reasons. An original design must be drawn carefully so that it can be built accurately. But photographs of completed buildings are important too, to convey and explain the character and style of a house to others.

You may well have seen drawings that have been made so that builders can construct a house. It is important to bear in mind that these drawings are prepared using certain conventions. This is so that everyone knows what to expect, from the person who is paying for the house to the council official who will want to discuss a planning application. It is also, of course, so that those who work on a building site know exactly what they are supposed to do, and can calculate the costs in advance.

There has been little change in the way in which a building is presented on paper since the seventeenth century. To ensure that all the necessary information is understandable, it is always shown using the following three methods:

A plan is a drawing of the layout of the rooms of a building. There must always be a separate plan for each floor – by looking out for the position of the staircase which connects between them one can easily see how the plans fit ‘on top of one another’. The plan will also show the doors and the windows, and all the built-in fitments such as wardrobes and (in a modern building) the kitchen and bathroom fittings. A plan is technically a downwards view of a horizontal slice through a building.

A section is a view of a vertical slice through a building. It is unlikely, of course, to show all the rooms, but it does clearly show many aspects which the plan cannot. It shows the height of the rooms, and therefore is the key to understanding how the staircase will look. It may also explain what the roof looks like, and how it stays up. If a building is making a feature of different room heights, a section may well be needed in order to explain what the effect will be.

The elevations are views of the walls of a building. Some of the internal elevations will appear on the sections, but the external ones need to be drawn separately. Although the architect may draw these last, because they are dependent on the plans and sections, it is of course the exterior aspect that is likely to interest other people most at first. A ‘facade’ is another word for an elevation of an external wall, but one that implies an elevation which is special or more important.

Plans, sections and elevations are indispensable tools when constructing or recording a building.

Matching the plans, sections and elevations of the same building requires going back and forward over and over again to achieve a balanced design. People who watch architects in restaurants are often amused to see them doodling all over the paper napkins – they seem obsessive scribblers. Now you know what they are doing, and why!

Architects have always tried to present their buildings in the form of three-dimensional drawings, and computer software now makes it easy to create accurate views in and around buildings. It is not unusual to see animated cartoon-like films that can give a realistic impression of what walking through a building will be like. Some architects actually use the techniques of computer rendering to inspire their designs for their buildings.

All drawings must be presented at a known scale – that is, as a fixed miniaturized proportion of the real thing – in order that dimensions can be checked using a special ruler. Now that nearly all drawings are done using computers, the architect actually draws at full size, which of course is reduced for convenience on the computer monitor itself; and printouts can easily be made at any scale at the press of the button.

All contemporary homes are extremely complicated objects. In order to record your own home thoroughly enough to rebuild it from scratch, you would need a whole series of drawings beyond the basic ones listed here. At the least you would need separate drawings for the electrical layout, the plumbing and the drainage, and the landscaping of the area outside; and you would probably also require detailed drawings at a large scale in order to convey sufficient information about the joinery and other internal fittings. It can readily be appreciated that the ability to draw accurately is an invaluable part of the architectural profession, and becoming familiar with architectural drawings will be an important part of your discovery of architectural history.

While a scale drawing is an invaluable tool, there are plenty of other ways of conveying what a building is really like. The most obvious one of all is clear from the pages of this book: photography.

A photograph, unlike a scale drawing, is not usually intended to provide an objective description of a building. More probably, it is there to show its character, and to emphasize what makes it special. Photography can highlight certain features, and of course it can enhance colours and contrasts. It is also a useful tool for pointing out common features between buildings, either by capturing a view of several buildings at once or by focusing on particular elements.

Both perspective drawing and photography are invaluable tools in recording architecture. Developing a skill at one of these is highly recommended for anyone who wants to analyse and discuss buildings.

There is another important way of recording architecture: writing about it. The history of style brings together all the different aspects of what a building looks and feels like as a continuous story. That is what the rest of this book is mainly about.

It is possible that you can now begin to compare the house you live in with others that you know: you already have a sense of what the important elements are. And yet we have not yet looked at the idea of architectural style.

All civilizations see themselves as part of an unfolding history. Ours is no different. We characterize past generations by remembering important dates and events, and associating them with changes that have come over society. The more people learn about the world, the more they want to express their own judgement about what seems important, and what lessons are worth remembering and repeating.

Architecture is like that. From time immemorial people have built using the materials that have come to hand. At certain times in history, structures have been erected in different places in the world that have seemed unforgettable: indeed, the more one looks at them, the more they seem to offer. Some ideas have been copied directly and others have been adapted. Many have come to be taken for granted. But in all cases it is the notion of style – of the common visual language of buildings of a certain type – that provides the key to understanding where these ideas have come from.

This history of architecture starts with the temples of ancient Greece, a civilization that had already lost its dominance two thousand years ago. The reason why these buildings are worth remembering can easily be learned by a trip to any historic town centre. There will certainly be buildings there, some constructed comparatively recently, that display characteristic Greek detailing; and there may be some that try on a tiny scale to imitate parts of a Greek temple. In order to understand why this might be, it is important to learn what Greek architecture had to offer, and to see how it fits into a long, continuing story.

At just the time when a Greek-style bank was being built in one part of your town, a gothic-style church might have been going up in another. The first building would have evoked feelings of solidity and responsibility; the second, an attempt to reconnect with the spirituality of the Middle Ages. Architects, and the people they build for, have always known that the style of a building carries certain associations. At the same time, they cannot usually go right back to imitate precisely a building from the distant past, because practical needs have changed. So the story of architecture is one in which designers are continually looking at ideas from the past and updating them in order to come up with something suitable. It is this that makes the story of architecture so dynamic and so exciting.

It may well be that at first glance your own home does not appear to occupy a distinguished position in the history of style and of past civilizations.

But that is unlikely to be true. Your house, whenever it was built, can tell you a great deal, and all you need to do is to learn to read it.

Looking for common features between your building and its neighbours is a good place to start. If you look at detailed maps in your local history library, you can probably work out when your house was built, and which other ones were built at the same time. Sometimes one can clearly see that a whole field, or the garden of a large house, was all built on at once.

Having done that, you can look for common features between your house and your neighbours’ – or others in the same area. Blocks of flats that were all built by a local authority during the same decade will probably have as much in common as houses built in a street by the same Georgian or Victorian builder. It will not take long for you to be able to identify which materials are the same, and whether they are characteristic of the area as a whole. You can make a list of all the features in your house which belong to the period in which it was built – you may have to pop into a neighbour’s house in order to be sure which ones are original if you think some have been changed.

Knowing when your house was built means that you can distinguish it from others in your town, and also what links it with other houses built at the same time. And this is where the story of architecture that follows will start to make sense. You will find to your surprise that although you live neither in a Greek temple nor a gothic cathedral, you can very probably identify common ideas with both.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, builders would commonly copy the features of ancient Greek or Roman buildings onto anything larger than a medium-sized house. They would imitate the grandness of these ancient structures by ensuring that the new house was symmetrical, with a door in the middle of the front elevation. They would give that door special importance by putting a miniature temple pediment over it. They would copy the stone mouldings from famous buildings that they knew or had heard of, and use them to decorate the corners and openings of their own construction. Architects who took a particular interest in the civilizations of the past, and who longed for order and elegance in modern times, might apply Greek columns to the front of a house, or even a Roman dome to the top of it. The result would never have been mistaken for a genuine temple, and yet at the time the references to classical antiquity are unmistakeable.

You do not have to live in an eighteenth-century Roman-style house, or a nineteenth-century gothic-style one, to be able to find references to the past. Many small terraced houses have tiny details around the front door or windows which were enough to add dignity to their otherwise economical form. Many mid-twentieth-century blocks of flats were designed by people who valued very highly classical ideas of proportion and who consequently put great store by the shapes of windows, or the overall forms of the blocks they designed. Others saw modern building necessities as a way of recalling the gothic principle of expressing function. A large chimney or a prominent balcony could easily be the modern descendants of a mediaeval manor house – improbable though that may at first seem.

Designers in the arts and crafts era of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were inspired by the solid workmanship of mediaeval times.

On top of all this, all buildings are part of the broader history of any nation. Building a new house is such an expensive project that it inevitably involves many, many people: not only those who will pay for it (which may include a bank rather than an individual!) but also those who will be involved in building it. That means that the final structure is in some way inevitably representative of the society in which it was built. That is one of many reasons why the history of architecture is so fascinating a subject.