In traveling around the state of Arizona, have you often

observed the word “Poston” on buildings and streets? Do you know about the town

called Poston? If you are shaking your head in puzzlement over your lack of

familiarity with the name, you are not alone. Yet, history and the very

existence of Arizona owe a debt of gratitude to a man named Poston.

After the 1500s, when the Spanish explorers had abandoned their

expeditions in search of the seven cities of Cibola, the fabled cities of gold

and treasure, Arizona became a forgotten place. Periodically a flag, Spanish,

Mexican or New Mexican, would be posted on its soil to reflect the current

political situation. Before the United States acquired Arizona, no more than a

dozen American mountain men and miners attempted to penetrate one of the few

places in the continent of North America that could boast of seven life-zone

levels. Until this country claimed the vast reaches of Arizona desert, mountain

and canyon, the land had been left unexplored, unconsidered and unwanted.

On December 31, 1853, just one day after the signing of the

Gadsden treaty, which purchased the southern section of Arizona from Mexico, an

exploring party sailed from San Francisco. This group was headed by a man, a

dreamer of utopias, who was destined to carve a territory and a state out of

this uncompromising wilderness, give it a name and force it to be recognized by

an unwilling and uninterested Congress.

His name was Charles Debrille Poston. Born in Hardin County,

Kentucky, on April 20, 1825, orphaned when he was just 12 years old, Charles

Poston studied the law, married, fathered a child and settled down to the life

of a practicing attorney much like his contemporary, Abraham Lincoln. But he was

a dreamer and a romantic with no outlet for his visions until the gold

discoveries in California inflamed the imaginations of thousands of people. Like

so many others, Charles Poston became hopelessly afflicted with the yellow

mineral fever.

Leaving his wife and daughter in the hands of relatives, he set

off for California, hoping to carve out a prosperous life for his family and

himself. Thus began an odyssey that would bring him equal portions of fame,

wealth, recognition, loneliness and poverty.

Taking on the position of chief clerk in the San Francisco

custom house, Charles Poston soon found himself in the employ of an agent for

the family of General Augustino de Iturbide, who had inherited a large grant of

land in what they believed was the new territory and wanted it located and

explored for its resources.

Poston helped organize an expedition of 30 men, including

several mining engineers, among whom was Christian Herman Ehrenberg. The party

sailed to Sonora, Mexico. The journey did not live up to the high expectations

of the leaders of the group. Their ship was blown off course. When they finally

were able to get back on route, moving toward their destination, their hopes for

a successful sea journey were further complicated. Caught in unexpected heavy

seas, the ship was dashed against the rocks. The men were barely able to reach

land safely before the ship sank. Once in Mexico, conditions did not improve.

They were greeted with hostility by the Mexicans, still angry over losing so

much of their land in the war with the United States. Eventually, after some

days of tense negotiation, Poston and the rest of the party were given free

access to travel to the new territory.

Their explorations revealed the many possibilities of this land.

Old Mexican silver mines were found. Specimens of gold, silver and copper were

collected. Decaying missionary churches were located. Although everyone searched

diligently for the boundaries to the Iturbide land grant, they were never found

and subsequently could not be established. But, by the end of the trip, Poston

and Ehrenberg were convinced that this new land had enormous potential.

Still in his twenties, Poston already showed his ability to

visualize the creation of new settlements, as well as his skill in cultivating

friendships that would help him in the promotion of this territory.

Charles D. Poston, the "Father of Arizona" (Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson. National Archives photo no. 111-B-3183)

Poston liked to tell a story about that initial journey. It

happened when the group had reached the Colorado River and were ready to return

to California. The only way to cross the river was by a ferryboat owned and

operated by a Louis J. F. Jaeger. Because of hostile Indians in the area, there

were risks involved in maintaining a ferry service. Therefore, Jaeger charged

exceedingly high prices for passage. Poston had neither the desire nor the funds

to pay the requested price to get his party across the Colorado. Jaeger refused

to lower the price. It was a stand-off with seemingly no solution.

Here is where Poston’s imaginative vision and resourcefulness

came into play. Looking around him, he realized that one day a town or city

would spring up on the banks of the Colorado River. Why not hurry the process

along with a little promotion, he reasoned. Turning to the rest of his party, he

suggested. “Let’s sell city lots to passing travelers and make our money for the

ferry that way.” “Sell city lots,” retorted members of his party, tired, hungry

and exceedingly disgruntled. “There’s nothing here but desert as far as the eye

can see.”

“True,” countered Poston with a convivial smile, “but eventually

a city will grow up near the river and Fort Yuma.” With that rare ability to

explain his vision of the future, Poston soon inspired the men with enthusiasm

for his plan. Under the skilled surveying directions of Ehrenberg, the men,

using sticks and stones and bits of string, began plotting out a city with a

town square, roads and pier areas along the river.

Jaeger, intrigued by this buzz of activity, came over to find

out what they were doing. With a show of salesman-like reluctance the men at

first hesitated to tell him of their scheme. When Poston finally shared their

plan with Jaeger, the ferryman was also caught up in that dream of the future

and immediately bought sufficient parcels of land to allow the party funds for

crossing the Colorado. In addition, many sites were sold in California, netting

members of the expedition a tidy sum.

In San Diego, Poston and his party recorded their townsite,

which was called Colorado City. Some believe that this was the beginning of

Yuma. Others state that Yuma was located further south and that Colorado City

never expanded to more than a temporary tent town.

Upon returning to San Francisco, Poston received a letter from

Kentucky informing him that his wife was seriously ill and not expected to live.

Poston quickly returned home. After a long convalescence, his wife recovered.

Poston felt that now he could leave his family and travel to Washington, D.C. to

see if it was possible to interest Congress in appropriating funds for further

exploration of the territory. While in Washington, he renewed the acquaintance

of Major Heintzelman, whom he had first met when the Major was in charge of Fort

Yuma. Heintzelman shared Poston’s enthusiasm for the potential of the area, not

only for the opportunities to acquire wealth, but for the chance to create new

frontier settlements. Both men realized that the United States was fast becoming

a country where the frontier was disappearing.

Together, the two men were able to persuade the Texas Pacific

Railroad to hire them to explore the land for a railroad route and to develop

its mineral resources. The generosity of this first business client allowed the

men to form the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company, with Heintzelman as its

president and Poston as its managing director. Ehrenberg became a director in

the new company, as well as its chief engineer and surveyor.

Money poured into this fledgling company and soon the directors

could boast of two million in capital and $100,000 in cash for outfitting the

expedition. Poston proceeded to San Antonio, which was considered at that time

the best outfitting place in the Southwest. A man given to the grand gesture,

encouraged by what seemed to be unlimited funds, he supplied the expedition

royally. Mules, horses and wagons were loaded with provisions of every sort.

There were tools, machinery, food, wines, clothing, books and many other

luxuries, so that the travelers on the rugged trails would be assured of every

possible comfort. All kinds of men flocked to join the expedition.

It took four months to travel the 762 miles to Arizona.

Initially the journey was a delight. The first military fort they came to was

run by a commander who was a

bon vivant

and had imported two French chefs to accommodate his culinary

needs. Pleased at having the company of a raconteur such as Poston, he

entertained his visitors lavishly. But such conditions did not last. A skirmish

with the Apaches and constant rain made the trip difficult.

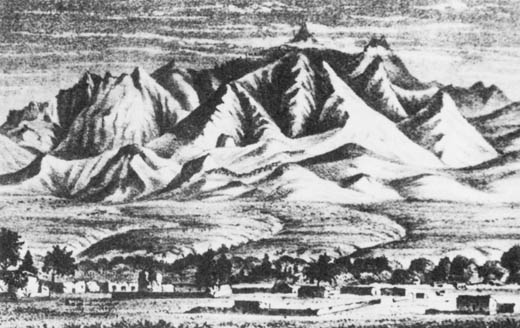

Tubac in 1863 with the Santa Rita Mountains in background (Courtesy Arizona Historical Society Library, Tucson)

Arriving in Tucson in August of 1856, Poston, ever sensitive to

the human condition and the general exhaustion of his party, gave the men a

two-week holiday to rest and participate in the festival of St. Augustine which

was in progress. After four months of traveling while remaining constantly alert

to the possibility of an Indian attack, traversing swollen arroyos, trekking

through mud and trailless areas, Poston knew that the men needed the fiesta to

help them overcome the stress and strain of the trip.

While his men were thus occupied, Poston had an important

decision to make. Where was he to locate the headquarters of this new company?

He could not choose a place where the lives of the men or the valuable property,

which had been hauled from such a long distance, would be risked. The

surrounding areas abounded in Apache Indians. He needed a place that could be

easily defended and still be in close proximity to mining operations.

He chose Tubac, located some 50 miles south of Tucson. It had a

presidio which had been abandoned by the Spanish. Tubac was nestled in a rich

valley at the base of the Santa Rita Mountains. Poston knew from his first land

grant expedition into Arizona that these mountains harbored old Spanish and

Mexican mines.

Poston and his men went to work cleaning up the crumbling adobe

fort, repairing buildings and corrals, replacing windows and doors. Some of the

men were sent into the nearby forest to cut lumber for furniture. Others planted

vegetable gardens. In a short while, Tubac had come to life and afforded its new

occupants a comfortable living style. Now the men devoted their energy to

finding and opening up the mines of the area. Soon silver deposits were bringing

in over a hundred dollars a day. When the immensely rich Heintzelman Mine was

discovered in Arivaca, riches began to pour into the new community.

Such activity did not go unnoticed and soon skillful Mexican

miners were arriving in great numbers to find work in the new enterprise. By

Christmas of that year, Poston discovered that he was in charge of a flourishing

community of over a thousand people. Others might have been overwhelmed by such

a burden of leadership, but not Charles Poston. The challenge of creating a

utopian community which would be at once vigorous yet leisurely and filled with

hope for the future was one he relished. Good meals and good conversation were

the standard of the community. Young Mexican senoritas, who had come to the

settlement in hopes of finding husbands, were a civilizing influence on the

rough-and-tumble miners. After a day’s work, music and festivities were a part

of the lifestyle.

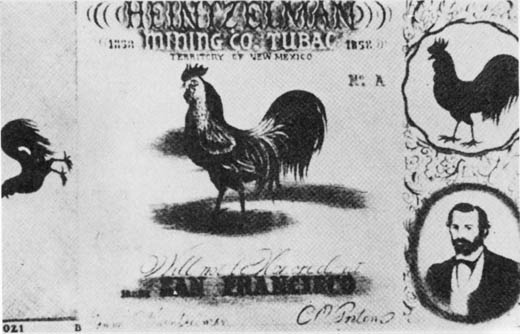

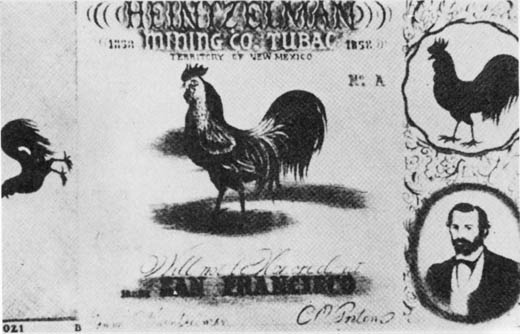

Poston even had paper money, redeemable in silver, printed for

the community, which helped to ease the day-to-day transactions for necessaries.

Since many of the settlers working for the company spoke only Spanish and many

of the miners hired by Poston spoke a series of European languages, Poston

devised a simple scheme for recognizing the value of this currency. Each bill

had a picture of an animal to help designate its value. Twenty-five cents was

represented by a calf, a rooster was fifty cents, a horse was a dollar and the

picture of a lion was valued at $10.

Poston, as a virtual dictator in this community, used his power

with generosity and kindness. He officiated at weddings and christenings, ever

mindful to make the occasion one of celebration. He granted divorces and had the

power to execute criminals and to declare war. So many of the community were

grateful to him for his official sanctions that many young children were named

after him. People flocked to Tubac. It was considered a safe, thriving place to

live, and the place where a couple could easily get married.

A "boleta" used by Poston as a medium of exchange at Tubac. This one was valued at fifty cents. (Courtesy Arizona Historical Society Library, Tucson)

The community flourished for several years in peace and harmony.

Only once, when a priest came to investigate the religious status of the

inhabitants and proceeded to declare all the marriages and the baptisms at which

Poston officiated invalid, did the situation in Tubac become tense. Couples,

many of whom identified with the Catholic church, began to realize that their

relationships were without legal standing. Poston, with his usual skill in

persuasion and in cultivating friendships, was able to persuade the priest to

redo all the previous ceremonies for an agreed-upon sum, thus making them

binding in the eyes of the church.

Production of silver and copper was climbing and the company

expected that it would soon be earning about $3,000 a day. Poston wrote in one

of his reports that he felt Tubac embodied the highest aims in human endeavor.

“Full employment, not only for wealth but also for the purpose of creating a

place of freedom and civilization in the territory, should serve as an example

to the rest of the nation. Our experiment must elicit nothing but pride and

admiration.”

But the bubble of euphoria was about to burst. Due to the

irresponsibility of settlers in the surrounding areas and the military stationed

at a nearby fort, several incidents occurred. This resulted in the reasonably

peaceful local Apaches taking to the warpath under the leadership of Cochise to

avenge the wrongful deaths of several of their chiefs. The Mexicans south of the

border also rose up in arms over what they viewed as blatant acts of aggression

and injustice. Add to this the beginning of the Civil War and the recall of a

garrison of soldiers stationed in the area for protection and Tubac was left

sandwiched between angry Mexicans and Apaches with no military back-up. Poston’s

brother, John, was one of the first victims killed in an attack on the

Heinzelman Mine.

Tubac had to be abandoned. Women and children were rushed to

safety in Tucson. Thus ended the prosperity and joy of this grand experiment in

community living for which so many had committed their lives and money. More

than a million dollars in stores and machinery, homes and supplies had to be

abandoned to destruction. The little farms that had taken hold around the

community soon reverted back to desert. Poston wrote at the time that the

loneliest sound he had ever heard was the crowing of the cocks on the deserted

ranches. “The very chickens seemed to know that they were being

forsaken.”

1

After returning home to Kentucky, Poston became involved in the

movement to split the New Mexican territory, separate the western half, and

create a new territory. The settlers in the Arizona half felt that the seat of

the territorial government in Mesilla was too far removed from them to

effectively give them adequate and protective support. Even the leaders of the

New Mexico territory were anxious to eliminate the burden of having to deal with

the Apache problem. But each time the bill came before Congress it was defeated

because of other pending problems, such as the issue of whether slavery should

be allowed in the new territory. The situation dragged on and on. Each new

petition was rejected because of another Congressional disagreement.

By now the Civil War was in full fury. Congress was looking for

ways to fund this exceedingly expensive war. What was needed was a new source of

gold and silver to infuse into the military in hopes of bringing this

destructive war to a quick resolution. Heintzelman, by now a general in the

Union army, had the ear of President Abraham Lincoln. Here was a perfect

opportunity to once again bring before Congress the mineral potential of Arizona

and the need to forge closer ties with the area by creating it as a separate

territory.

General Heintzelman recalled the magical enthusiasm that Poston

could bring to a speech. In Heintzelman’s mind, Charles Poston was that perfect

combination of talents to successfully take up Arizona’s cause in Congress.

Poston had much firsthand knowledge of the area. He personally knew of the

mineral wealth, but most of all he had that ability to persuade and charm, to

create with words a vivid vision, a dream of the potential of the place.

General Heintzelman set up a meeting with Poston and his fellow

Kentuckian, President Abraham Lincoln. The President listened carefully and then

sent Poston to men who had the power to get a bill creating an Arizona territory

through the Congress. Once again Charles Poston, with his natural ability as

promoter, raconteur and visionary, used those talents to persuade these powerful

political men. On February 24, 1863, the results of Poston’s persuasive

abilities came to fruition, and President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill creating

the Arizona Territory.

A jubilant Poston invited these new friends and political

colleagues, who had worked for the success of the bill, to a celebration dinner.

As the evening progressed, the wily politicians began to parcel out the jobs and

positions that this new territory had created. Poston, even though host and

catalyst, was ignored. Astounded by this blatant disinterest in rewarding him

for his labors, Poston fortified himself with several glasses of wine and

exclaimed to his assembled guests, “Well, gentlemen, what is to become of

me?”

2

Eventually he was offered the office of Superintendent of Indian

Affairs. This was not a powerful nor lucrative position, but it did give Poston

his opportunity to return to his beloved Arizona.

Having outfitted himself and his party in what was by now his

personal style of comfortable travel, Poston, armed with many gifts for the

Indians, invited a friend from San Francisco to join him on his journey through

Arizona as he visited the various Indian tribes. It might be easy to dismiss the

skill of Charles Poston as superintendent of the Indians because of his penchant

for luxury, drama and good times, but he was and had always been a keen observer

of the precarious conditions under which the Indians lived. Their living style

was to be in even greater peril because of the rapid encroachment by settlers on

their hunting, farming and foraging lands. The visionary, the dreamer, did much

in the way of coming up with constructive ideas to better the lives of the

Indians.

Poston also knew how to use the skills of others to give his

plans a firm foundation. He hired an engineer to help him create a plan for a

proposed Indian reservation along the Colorado River, which would make use of

canal irrigation for fertilizing the farmland. By developing an irrigation

program, he was making certain that the Indians would be able to be

self-sufficient in supplying themselves with food, but it would be done in a

manner that was based on a successful irrigation system told about in the

familiar Indian tales of the ancient ones from a time long ago.

Poston was able to persuade the territorial legislature to agree

with the proposal. Then he ran for the office of territorial delegate to

Congress. This would allow him to personally present his proposals for the

Indians. As a delegate, Poston presented more than 10 resolutions concerning the

needs of this fledgling territory. In addition, he gave eloquent speeches in

support of his Indian programs. Much of his vision did not interest the men in

Washington, D.C. Few had the foresight to see the Indians as anything more than

savages to be ignored or eliminated. Some token bills were passed which gave

small amounts of money for incidental expenses, such as supplying the Indians

with farming equipment, but without the canals of irrigation, the money was a

mere assuaging of conscience.

Three years after Poston’s plea for the Indians, Congress did

pass a bill setting up a small reservation with the start of some irrigation

construction. It was better than nothing, but had Poston’s vision for the

Indians been followed, perhaps much of the hate and tragedy that occurred in

Arizona between the settlers and the native Americans might have been

averted.

But, long-range visions are not the stuff of politics. In what

appeared to be some political collusion, Poston found himself in a three-way

contest for re-election as territorial delegate to Congress. All three

candidates ran on the same ticket and Poston lost.

Returning to Washington, where he began to practice law, Poston

still hoped to realize his political ambitions. He had become a friend of

President Lincoln and was viewed in Washington as a man who had the right

connections and influence. All this came to an abrupt end some few months later

with the assassination of the President. Without his fellow Kentuckian’s

support, there was little call for Poston’s services.

Returning to Arizona, he tried once again to be the successful

candidate for delegate to Congress. Again he was defeated. Rejected by a place

that meant so much to him, the relentless Poston went to Europe and wrote a book

about his experiences. Returning to Washington, Poston was commissioned by the

Secretary of State to go to Asia to study irrigation and immigration.

Everything about Asia fascinated him. Armed with a treaty to the

Emperor of China and many letters of introduction, he met not only the Emperor,

but the Mikado of Japan, the Viceroy of India, the Khedive of Egypt, the Sultan

of Turkey, the Shah of Persia and the Kings and Queens of Europe. Much later, he

was to remark that none of those great leaders embodied the majesty of humanity

that he had found in Abraham Lincoln.

While in India, Poston was to discover the Parsees and their

ancient Zoroastrian religion. These were the Sunworshippers who believed in the

prophet Zoroaster, who had lived one thousand years before Christ, and espoused

the continuing universal struggle between the forces of light and darkness. The

Parsees fascinated Poston with their belief that man can choose to take part in

the struggle against the elements of darkness by worshipping and supporting the

Lord of Light, who is eternally engaged in the battle against the forces of

evil.

Poston was so taken by this religion and the study of its

history and temples that he was accused of neglecting the study of ditches and

irrigation. When Washington heard about Poston’s use of time, his commission was

withdrawn. Poston continued his travels, supporting himself by writing articles

about his experiences. For awhile he lived in England, where he wrote a book

about his new-found religion. His charm, his vision, his enthusiasm opened many

doors and Poston was sought after as a speaker and writer. Still desirous of

holding political office, Poston decided to return to Washington. But his

political ambitions were to bear no fruit.

With a sick wife in Washington, Poston needed a source of steady

income. Although he was a man who had met and known the rich and famous of the

world, the only appointment that was offered him was the position of Register of

Land in Florence, Arizona. Florence had a population of 500 when Poston arrived.

He worked in a small adobe room at a modest salary and was to remain there for

the next four lonely years. There was little to interest a man who had lived in

such exciting capitals as Washington, D.C., and London. He wrote a book. He took

to exploring the area.

One day he noticed a hill whose shape was reminiscent of an

Egyptian pyramid. On that hill he found the ruins of a stone tower. Poston began

to wonder if those ruins were not the product of some ancient Indians, the

forebears of the Hohokam, perhaps even the Aztecs, who had brought the religion

of Zoroaster and the worship of the sun to Florence thousands of years

ago.

If this was so, perhaps the fates had brought him back to

Arizona, to this tiny insignificant place, because of his knowledge of that

eastern religion. Was he meant to discover, to recreate, to bring back to full

flourishing the ancient practices of Sunworshipping? He built a road up to the

tower on the hill at his own expense. He wrote to the Shah of Persia to enlist

his help in recreating in this Arizona desert a temple to the Shah’s ancestors

who worshipped Zoroaster. He wrote articles publicizing his findings, hoping to

encourage those who might wish to follow this religion and help support his

efforts.

He entertained in a home he had built beside his hill. He

invited all his friends to come and celebrate his vision. He would build a

temple of the sun at the apex of the hill. Champagne was drunk, gourmet food was

eaten, fireworks lit up the midnight sky, the flag to the sun was raised, a new

community of worshippers was to begin.

But funds were not forthcoming. The Parsees showed little

interest in a temple in a distant desert far across an ocean. His ability to

excite others with his vision waned. It was too strange a dream, too mystifying,

too far outside the realism of life in Arizona. Discouraged, he resigned from

the land office commission.

The next years of Poston’s life found him employed as a customs

officer at various settlements along the Mexican border. At one point, he was

placed in charge of an agricultural experiment station in Phoenix. But the

promise of his early opportunities brought nothing more than a slow and steady

decline in prestige, position and the acquisition of money.

Arizona, the place he had helped to birth, gradually forgot

about him in his old age. He would eventually live in Phoenix in near squalor

until the legislature, having become aware of his straitened circumstances,

presented him with a modest pension of $25 a month.

Charles Poston died in June of 1902. At 75 years of age, he was

totally alone. The Father of Arizona had been forgotten by all. His body lay

unclaimed in Phoenix as attempts were made to locate relatives. Burial in the

local potters’ field seemed to be imminent. Then the editor of the

Arizona Republican

wrote an article asking the pioneers and citizens of Phoenix to

help. Hundreds offered to help in the funeral arrangements.

Twenty-three years after his death, the citizens of Arizona

decided to honor the man whose own life was so completely intertwined with

Arizona’s history. What more fitting honor could be bestowed than to acknowledge

his last great vision. A small stone pyramid tomb was created on top of his

peaceful hill in Florence. His remains were transferred there. Now Charles

Poston can forever rest in the sun that shines so steadily on the land he helped

to establish.

Gressinger, A. W.,

Charles Poston, Sunland Seer

, Dale Stuart King, Publisher, Globe, Arizona, 1961.

Hall, Sharlot, “The Father of Arizona,”

Arizona,

The New State Magazine

, Volume II. Number 10, Phoenix, Arizona, August 1912.

Poston, Charles D., “Building a State in Apache Land,” four

articles,

Overland Monthly

, July 1894, August 1894, September 1894, October 1894, Volume

XXVI, Numbers 39–42, Overland Publishing Company, San Francisco. Edited by

Rounsevelle Wildman.

Smith, Dale, “Sonoran Camelot,”

Arizona Trend,

Volume 3, Number 12. Phoenix. Arizona, August 1989.

Wagoner, Jay J.,

Arizona’s Heritage,

Peregrine Smith, Inc., Santa Barbara and Salt Lake City,

1977.