In 1855, Jefferson Davis, the head of the War Department, was told by Congress to try a daring new idea. The plan was to import camels to the United States and use them for desert travel. Since camels were so successful in Egypt, Arabia, and Turkey, thought government strategists, surely they could also be used in the deserts of the Southwest. Thirty thousand dollars were appropriated for the project and in 1856 Major Henry Wayne was assigned the task of purchasing camel for the United States. Uncle Sam was in the camel business.

Now, not everyone thought that buying camels for the Army was such a wonderful idea. “Sounds like a hump-dinger of an idea to me,” said one witty observer. “Those boys in Washington must have humps on the brain,” quipped another. Most folks simply shook their heads in disbelief. Camels, those funny-looking humped things you saw in circuses! Could they keep up with horses? Could they carry as much as a mule? Would they need fancy foreign foods to eat? Would they work? The War Department was determined to find out.

Major Wayne’s orders were simple. First, learn all you can about camels, then go to the Middle East and buy the best stock available.

The first place Major Wayne visited was the London Zoo in England. There he learned how camels adapted to living in captivity. Then he went to France and met with French soldiers who had used camels in North Africa. They told him how camels could be used for travel in harsh terrain. Next, he went off to Florence and Pisa, in Italy, where camels were bred by the royal Dukes of Tuscany. There he was shown that camels were tough beasts of burden who could easily adapt to extreme variations in climate.

When he finally reached the Middle East and started to buy camels, he discovered that most of his learning came from working with the animals themselves. Slick operators tried to sell him diseased, miserable old street-camels at outrageous prices. By necessity, Major Wayne had to learn a lot about camels very quickly and the more he learned, the more excited he became. Not only would camels solve the Army’s problem but here was a wonderful new money-making opportunity for people in the United States.

He could see it all. Camels to carry thousands of pounds over arid desert lands. Camels to backpack cotton for Southern plantations. Camels to swiftly follow attacking Indians. Move over mules and horses; camels are going to revolutionize the American way of life!

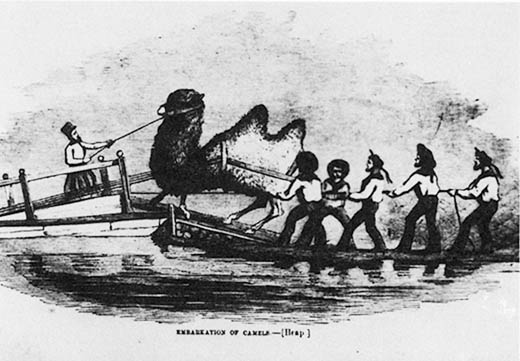

The next challenge for Major Wayne was to get the camels to the United States. A Navy ship had been commissioned for the job, but getting thirty-three camels on board wasn’t easy. The big dromedaries didn’t take kindly to being pushed and shoved into strange places. The deck of the ship actually had to be cut away to provide enough head and hump room for them.

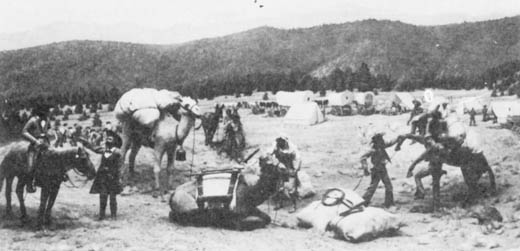

In spite of these difficulties and the Navy personnel’s lack of experience, the camels arrived safely in Texas. In fact, a few births had even taken place during the voyage. Now the project was turned over to Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale. His assignment was to take the camels across the area now known as Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, and on to California through rough terrain and uncharted areas. If the camels could make it successfully, then a series of army posts would be established to relay mail and supplies across the Southwest.

Embarking camels onto U.S. Naval ship bound for Arizona (Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson, Arizona)

At first things did not go well for Lieutenant Beale. His men did not know how to handle the exotic beasts and the camels were out of shape from their long confinement on board ship. But with the help of two handlers hired for the purpose, the Americans soon began to learn. The handlers were Greek George and a man from Turkey named Hadji Ali. Hadji’s name was much too complicated for the Americans to pronounce and he soon became known as “Hi Jolly,” a name that was to stay with him for the next fifty years.

When Lieutenant Beale first accepted his assignment, he did so with a degree of good-natured humor. What else could he do about the situation in which he found himself? But as the journey progressed across the Southwest, his amusement soon changed to avid enthusiasm.

Camels were docile. Each could carry over a thousand pounds and travel forty miles a day without tiring. They ate anything available and seemed content with greasewood shrubs and cactus, plants no horse or mule would touch. They could also go for days without water and even ended up carrying water and food for the mules and horses when such items became scarce. They could travel faster than horses, swim swollen rivers, climb mountains and survive in conditions of two or three feet of snow. Everywhere Beale went people crowded around his dromedaries, fascinated. He became convinced that camels were the animal answer for the Southwest.

Predictably not everyone agreed. Initially, horses and mules stampeded at the sight of these strange animals. Handlers had to learn a whole different way to deal with them and often didn’t care to learn. Nonetheless, by the end of the journey, the experiment appeared to be a success.

After such a promising beginning, have you begun to wonder why we don’t see camels everywhere? Why are there no camel farms, camel shows and camel races in Arizona? Why are there no cowboys with their faithful companion, the camel? What happened?

Everything changed overnight. The long years of conflict between the Northern States and the South exploded into a Civil War. No longer could the military afford to keep isolated desert outposts for mail and supply service. Troops now needed for the war were withdrawn from the Southwest. Urgent military orders prevented Major Wayne and Lieutenant Beale from continuing to support these fascinating animals. In the confusion of war, camels were forgotten.

In time, a few were sold as pack animals, but the majority were simply allowed to escape into the desert. For many years they could be seen wandering in the foothills around the Gila and Colorado rivers. Eventually some were shot, some were captured, and some just disappeared.

Yet, the legacy of the camel experiment lingered on. About thirty years later, a camel was captured by a man from the Fort Yuma area. Here, he thought, was a way to make a little easy money. His scheme was to take the animal to Phoenix and sell it to the highest bidder. Surely someone would want to buy this exotic beast. But no one wanted to purchase his dromedary. Having invested considerable time and money into his venture, the man became desperate. What was he to do?

He owed money to a man in Phoenix and tried to give him the camel as payment for the loan. Knowing some information the other did not, the Phoenix man happily took the animal. A circus was scheduled to come into town in the next month. The new owner was certain that he could sell the camel to the circus and realize a handsome profit. Now all he had to do was take care of the animal until the circus arrived.

Lt. Edward F. Beale, disguised as a Mexican for his perilous ride across Mexico bearing dispatches telling of the discovery of gold in California and a sample of the gold (Courtesy Arizona Historical Society, Tucson)

That task proved more complicated than anything he had imagined. He asked a friend if he could board his camel in the alfalfa field where the friend kept his mules. The man agreed and that evening the camel was put in the field. The next morning disaster met their eyes. Every mule, frightened by this uncouth alien, had tried to escape. Each was caught up in the barbed wire fence, while the camel was happily eating all the alfalfa in sight. The owner of the field promptly demanded that the camel be removed.

Next, the man decided to leave the camel in his own back yard. But that didn’t work either. Every time the lady next door would attempt to drive by in her horse and buggy, the horse, upon seeing the camel, would rear up and try to jump into the buggy with the lady. She complained to the officials. The camel had to go.

The owner needed to come up with a new plan. Another friend of his owned a popular saloon next to which he kept a stable. Why not put his camel into the barn until the circus arrived? The animal could entertain the saloon’s customers and hopefully stay out of mischief. But the barn door was not tall enough and no amount of pushing and shoving could persuade the camel to go inside. Eventually, the barn door had to be enlarged. None of this helped the disposition of his friend, or of the camel, who stayed sulking in the barn for a week refusing to eat or drink. Then one night, the camel proceeded to eat everything in the barn, including some bailing wire, kick open the door and escape down the street. After all these difficulties, the owner congratulated himself on being relieved of a major nuisance.

But the night had only begun and before it was over, that camel would be remembered in Phoenix for dozens of years.

The first incident occurred in the early morning hours. A rancher was bringing into Phoenix a wagon heavily loaded with hay. He had decided that he would test out a skittish new team of four mules. One moment he was quietly riding along the road, next to the canal, congratulating himself on his smooth handling of the team. The next moment he noticed some strange shambling object coming swiftly down the center of the road. That was the last thing he remembered until he awoke to find his mules hightailing it off in all directions and his wagon in the canal sinking fast.

A few minutes later, a little farther up the road, a butcher was driving a large herd of hogs to market. After months of carefully feeding and fattening his animals, he was dreaming, in the stillness of the early morning, of his impending profits. Suddenly, he caught a fleeting glimpse of something coming down the middle of the road like a stampeding tornado. Bare moments later, the butcher was left standing alone on the bank of the canal, viewing a hogless landscape. Distant grunts and terrified squeals came from all directions. For weeks afterward, the local newspapers ran articles of hog sightings from all over Phoenix.

Was it over? Not yet. Before the camel disappeared into the desert, he left a trail of upset buggies, frightened horses and irate citizens. As for the hapless owner, he quickly left town.

Are there any camels still left wandering our vast desert areas? Probably not. But the legend lives on.

Some say their ghosts remain. Occasionally, at twilight, one can see a huge red camel wandering out on the desert. On its back sits the bleached skeleton of a man, who many years before, dying of thirst, strapped himself onto the camel, hoping that even if he became unconscious, the camel would eventually lead him to water.

Others say that the ghost of a crazy old prospector can still be seen roaming the hills with his three faithful camels, loaded with a treasure of gold.

After the Civil War, the army never resumed its experimenting with camels. Railroads eventually solved the transportation problems across the Southwest. Time makes recollections vague, but until his dying day, the Turkish handler, Hi Jolly, swore that there were camels out there. Are some of their descendants still roaming our desert? I don’t know, do you?