Greta Zimmer stood motionless in Times Square near a replica of the Statue of Liberty and a model of the Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. To Greta’s left was Childs restaurant, one of several in New York, including this establishment at 7th Avenue and 44th Street. But Greta did not come to Times Square to stare at statues or belly up to bars. She wanted to read the Times zipper and learn if Japan really had surrendered to the United States.

With the 44th Street sign and the Astor Hotel to her back, she looked up at the tall triangular building that divided one street into two. The lit message running around the Times Building read, “VJ, VJ, VJ, VJ . . .” Greta gazed at the moving type without blinking. A faint smile widened her lips, and narrowed her eyes. She took in the moment fully and thought, The war is over. It’s really over.

Though Greta had arrived in Times Square by herself, she was not alone. While she continued to watch the moving “VJ” message, hundreds of people moved around her. Greta paid little attention to the swelling mass of humanity. But they were about to take notice of her, and never forget what they saw. Within a few seconds she became Times Square’s nucleus. Everybody orbited around her, with one exception. He was drawn to her.

Fresh from the revelry at a Childs on 49th, George Mendonsa and his new girlfriend, Rita Petry, made their way down Times Square toward the 42nd Street subway station. Rita fell behind George by a few steps. Meanwhile, Eisenstaedt, who a short time earlier had snapped a photo of women celebrating outside a theater entrance, persisted in his hunt for the photo. After traveling a block or so up Times Square, he took notice of a fast moving sailor he thought he saw grabbing a woman and kissing her. That sailor was heading quickly south down Broadway and 7th Avenue. Wondering what the sailor might do next, Eisenstaedt changed direction and raced ahead of the darting sailor. Doing so was not without its challenges. He had to work through and around many civilians and servicemen who moved all about Times Square. As Eisenstaedt approached the 44th Street sign, he continually scanned the scene ahead of him for the least encumbered pathway. To avoid bumping into people in the crowded street, he had to look away from the sailor he was trying to track. When glancing over his shoulder, he struggled to regain his focus on the Navy man wearing the formal Navy blue uniform. As he did so, Greta looked away from the Times zipper and started to turn to her right. George crossed the intersection of 44th Street and 7th Avenue, lengthening the space between him and Rita. The photographer, the sailor, and the dental assistant were on a collision course.

With a quickening pace that matched the surrounding scene’s rising pulse, the sailor who served his country on board The Sullivans zeroed in on a woman whom he assumed to be a nurse. The liquor running through his veins transfixed his glassy stare. He remembered a war scene when he had rescued maimed sailors from a burning ship in a vast ocean of water. Afterward, gentle nurses, angels in white, tended to the injured men. From the bridge of The Sullivans he watched them perform miracles. Their selfless service reassured him that one day the war would end. Peace would reign again. That day had arrived.

George steamed forward several more feet. His girlfriend was now farther behind. He focused on Greta, the “nurse.” She remained unaware of his advance. That served his purpose well. He sought no permission for what he was about to do. He just knew that she looked like those nurses who saved lives during the war. Their care and nurturing had provided a short and precious reprieve from kamikaze-filled skies. But that nightmare had ended. And there she stood. Before him. Far from the attacking enemy. Close to home. With background noises barely registering, he rushed toward her as if in a vacuum. The last step and the second before his encounter with the shape of a woman in white squeezed out the remaining space between them. Though George halted his steps just before running into Greta, his upper torso’s momentum swept over her. The motion’s force bent Greta backward and to her right. As he overtook Greta’s slender frame, his right hand cupped her slim waist. He pulled her inward toward his lean and muscular body. Her initial attempt to physically separate her person from the intruder proved a futile exertion against the dark-uniformed man’s strong hold. With her right arm pinned between their two bodies, she instinctively brought her left arm and clenched fist upward in defense. The effort was unnecessary. He never intended to hurt her.

As their lips locked moistly, his left arm supported her neck. His left hand, turned backward and away from her face, offered the singular gesture of restraint, caution, or doubt. The struck pose created an oddly appealing mixture of brutish force, caring embrace, and awkward hesitation. He didn’t let go. As he continued to lean forward, she lowered her right arm and gave over to her pursuer—but only for three or four seconds. He tried to hold her closer, wanting the moment to last longer. And longer still. But they parted, the space between them and the moment shared ever widening, releasing the heat born from their embrace into the New York summer afternoon.

The encounter, brief and impromptu, transpired beyond the participants’ governance. Even George, the initiator, commanded little more resolve than a floating twig in a rushing river of fate. He just had to kiss her. He didn’t know why.

For that moment, George had thought Times Square’s streets belonged to him, but they did not. Alfred Eisenstaedt owned them. When he was on assignment, nothing worth capturing on film escaped his purview. Before George and Greta parted, Eisenstaedt spun around, aimed his Leica and clicked the camera’s shutter release closed four times. One of those clicks produced V-J Day, 1945, Times Square. That photograph became his career’s most famous, LIFE magazine’s most reproduced, and one of history’s most popular. The image of a sailor kissing a nurse on the day World War II ended kept company with Joe Rosenthal’s photo of the flag rising at Iwo Jima. That photo proudly exemplified what a hard-fought victory looks like. This photo savored what a long-sought peace feels like.

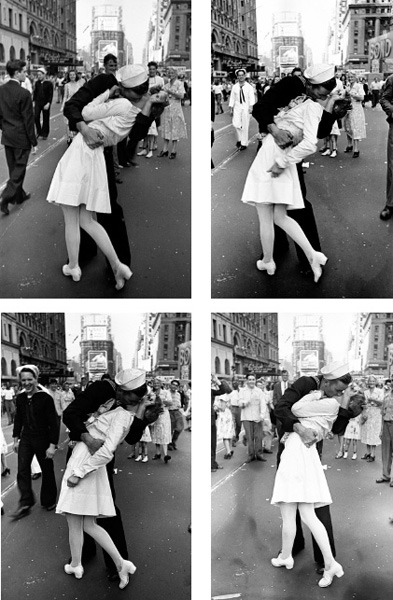

12-1. Alfred Eisenstaedt photographed this kissing scene in Times Square during the afternoon of V-J Day, August 14, 1945. The second photograph (top right) in the sequence became LIFE’s most prized photograph. (Permission granted by Bobbi Baker Burrows at Time-Life.)

12-2. Eisenstaedt’s first photograph.

12-3. Eisenstaedt’s second photograph, V-J Day, 1945, Times Square.

12-4. Eisenstaedt’s third photograph.

12-5. Eisenstaedt’s fourth photograph.

Alfred Eisenstaedt was not the only photographer to take notice of George and Greta. Navy lieutenant Victor Jorgensen, standing to Eisenstaedt’s right, fired off one shot of the entwined couple at the precise moment the LIFE photographer took his second picture of four. Though Jorgensen’s photo did not captivate audiences to the same degree that Eisenstaedt’s second photograph did, Kissing the War Goodbye drew many admirers as well.

And then it was over. Shortly after the taking of V-J Day, 1945, Times Square, Greta returned to Dr. J. L. Berke’s dental office and told everyone present what was happening on New York City’s streets. Dr. Berke had Greta cancel the rest of the day’s appointments and closed the office. Afterward, as Greta made her way home, another sailor kissed her, but this time politely on the cheek. For this kiss Greta no longer wore her dental assistant uniform and no photographers took her picture. And as far as she could tell, she had not been photographed at any point in time during that day. She did not learn otherwise until years later, when she saw Eisenstaedt’s photograph of a Times Square couple kissing in a book entitled The Eyes of Eisenstaedt.

George did not realize that he had been photographed, either. When George turned from the act he instigated, he smiled at Rita and offered little explanation for what had transpired. As hard as it is to believe, she made no serious objection. George’s actions fell within the acceptable norms of August 14, 1945, although not any other day. Actually, neither George nor Rita thought much of the episode and proceeded to Rita’s parent’s home via a 42nd Street subway train. Later that evening, the Petrys transported George to LaGuardia Airport for a flight to San Francisco that left at approximately midnight. Neither he nor Rita discovered Eisenstaedt’s V-J Day, 1945, Times Square until 1980.

12-6. Lt. Victor Jorgensen snapped this photograph at the exact moment Alfred Eisenstaedt took his second photograph of the 1945 V-J Day kissing sequence. (National Archives photo #80-G-377094)