3

WITHIN THE NEXT WEEK, other than several other social events with my fellow Yanks and endless knockings on my door by people trying to sell me memberships in everything from the Film Society to the Communist Club, there were two important meetings. The first occurred when an undergraduate tapped on my door, advanced a step, took one look at me at my desk as late afternoon light crept through my Meadow window, and with no particular scorn in his voice (though with a slightly wry smile) said “I don’t suppose you’d be interested in soccer.” It was not a question. At that point his smile became a grin as he stood on in my doorway, in case I chose to surprise him. Did I look that hopelessly unathletic; and after my first Oxford haircut, was I still that ineradicably American looking (he’d said soccer, not the more British football)?

I said I probably wasn’t interested, though in high-school gym I’d played it without the shame I earned in baseball and basketball. By then I’d turned my chair to face him. His was, again, another unmistakably English face but a markedly well-shaped one, topped with blond hair in unarranged rings as in one of Leonardo’s late drawings of floodwater. So I repeated that he probably didn’t want me on the college team—it was the Merton team he was promoting. Then I stood and invited him in for coffee—powdered coffee but still a beverage that seemed to connote manly vigor more nearly than the tea for which I was only just equipped.

The Hon. Secretary of the Football Club accepted, took a seat; and before we finished our first cups, we were further along toward a mutual liking than I’d so far anticipated with an Englishman. His name was Michael Jordan (not a relation of the later basketball star). Like Mayr-Harting and Gilchrist, Michael was also in the second year of history. He’d lived in Canada with his mother’s sister for a year in early adolescence, and he was “very keen indeed for classic jazz.” With his likable baritone speaking-voice (which became a bass when he laughed) and an accent that, while not supremely Oxonian, was clear and mildly upper-class, he had the poised cool I’d expected of my college friends.

My trunk contained no record player and I owned few jazz records—though I’d already liked both Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington in concerts at Duke—but I tried to wing my way here with Michael, pretending to more jazz expertise than I possessed. He lightly corrected my errors, knowing the details right back to King Oliver and beyond. We talked our way on in to glasses of sherry; and then he trotted off to his room in Rose Lane, beyond the college garden, to don his gown and meet me at the steps of the hall for seven o’clock dinner. We sat amid a cluster of his history and football friends, and much welcome laughter consumed us as they consumed rapidly (to my amazement) a monumentally awful dinner of tasteless fish, brutally roasted potatoes, and sodden gray cabbage. I ate enough to insure survival, then went to Michael’s smaller but unusually orderly rooms for after-dinner coffee and more talk—this time about movies, I think—on into late evening when I found my way through the towering dark trees, and the mumbling spirits, back toward my straw bed.

* * *

The second important early meeting soon followed the first when I received a crabbed handwritten note from my potential thesis director, a man named J. B. Leishman (he had presumably been assigned by some member of the English faculty, as it was then called). He was inviting me to call upon him, very soon, in his home in the Victorian awfulness of nineteenth-century north Oxford. I’d hoped to work with the famed C. S. Lewis, a distinguished Miltonist—among other things. But though Lewis had spent virtually his whole life at Oxford, he’d only just accepted a post at Cambridge. Though Leishman was not a member of Merton—he was a lecturer at St. John’s—he’d published numerous essays and books in the field of what was then called Elizabethan and Jacobean literature. I’d heard of him in yet another of his connections. For a year I’d owned and attempted to comprehend the translation of Rilke’s exciting but obscure Duino Elegies which he’d made with the poet Stephen Spender.

When he answered my diffident knock then, I expected a scholar in the picturesque Oxford mold—a tangled mane of rusty white hair, Benjamin-Franklin-style half-glasses, and dandruff-dusted clothes. Not at all. With virtually no pause for introduction, Mr. Leishman led me toward a large sitting room on the ground floor, motioned me toward a chair, then stepped to his mantel and continued standing as he proceeded—before anything else—to note my origins at Duke and then commence deploring a book on Paradise Lost by one of my professors there. That was Allan Gilbert, an admired American Miltonist with whom I’d studied in my senior year; his enthusiasm had proved especially contagious. Young as I was, in under two minutes Leishman’s continued and inexplicable attack had begun to rile me. In another few minutes it became clear that Leishman had reviewed Gilbert’s book in a professional journal and had satisfied himself that the volume was therefore buried forever (along with any enduring Gilbertian allegiance which I might be nursing).

Later years have let me see that Gilbert’s book is a little dotty but is also usefully provocative and never boring—considerably more than can be said for a great deal of the work of J. B. Leishman (an immensely learned scholar, in six languages, his work is almost uninterruptedly dull; and his Rilke translations are astonishingly poor). As an introduction to me, however, Mr. Leishman had—pompous as it may sound in the mind of a scholar as young as I—stepped off on a very wrong foot (eight years later he would die by stepping off a mountain in Switzerland). And as I continued to sit beneath his tirade, which included further deplorings of “you Americans,” I had ample time to take him in.

Far from the dusty geezer I’d expected, he was a man in his early fifties, dressed entirely in shades of brown—a thorn-proof brown tweed jacket with a brown pocket handkerchief, brown knickerbockers (our men’s knickers) with brown stockings, and a brown silk scarf (what Americans call an ascot). I wondered if he’d somehow devised this costume for my visit, but The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says that this was his “inevitable” dress, and The Oxford Magazine described his appearance as that of “a genial and benevolent witch.” On first encounter, those adjectives failed to occur to me, though his get-up did strike me as entirely original, winningly comic, and no doubt memorable. I’d soon deduce that he was a bachelor gentleman who kept open house on Thursday evenings for his male students.

At the time I was too impressed by the consistency of his attire and the fervor of his tirade to release the laughter that rose in me in increasingly powerful waves. I kept my seat and, given a chance at last, I told him a little about my intent to write a thesis on Milton’s play Samson Agonistes. He grumbled for a while longer about the unlikelihood of my being prepared for such an effort, especially if this Professor Gilbert had taught me; but we somehow got to near-dusk without an untoward external incident.

Then he showed me back to the door with a final insistence that I begin to attend his “Thursday evenings” for “wine and good talk.” I never did. In fact, I saw him only once more in the course of that whole term—a second meeting when he went on cranking his hurdygurdy’s repetitive “you Americans,” as though a twenty-two-year-old Yank was too simpleminded to realize that his own lower standing in the hierarchy of this till now infallibly courteous institution was being justified by this brown-knickered witch.

Strangely enough, my first meeting with Mr. Leishman failed to depress me. In all my years of formal education in America, I’d encountered only one really bad teacher, a woman in the fourth grade. Too many arresting British novelties were breaking round me by the hour for a single bizarre academic to cause grave discouragement—not yet. Furthermore in the first two or three weeks of the eight-week term, I was discovering that—far from living up to their reputation as icily reserved and culturally superior pricks—the Brits I’d met (with the exception of J. B. Leishman) were generally proving to be no more chilly or superior than the run of Americans in any sizable town.

They were helpful and pleasantly curious about me and my needs (young Americans were far scarcer at Oxford than now, and even Mr. Leishman had his evenings). From my student colleagues, their teachers, and their world, I was learning a dozen facts and skills per day—not to mention the acquisition of a virtually new language and accent, or a dialect of English that amounted to a far more distinct language than I’d anticipated from the courtly but emotionally resourceful language of the upper American South that I’d spoken for two decades and in which I’d begun my written fiction, poetry, and critical essays.

At least half my conscious mind, then, was beginning to be rewarded by thought of my oncoming work, by most of my new teachers, and several promising friends. So my bout of uncertainty as to the wisdom of being here had retreated for now. And soon I’d learn that the elastic rules of the English faculty would yield up a welcome access to someone other than Mr. Leishman.

In the first full week of term, after all, I’d attended the lectures of the famous Helen Gardner on the metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century (John Donne and George Herbert prime among them). I’d also joined a highly informal seminar—Lord David Cecil’s in practical criticism. And I’d begun, with my twenty-odd fellow B.Litt. aspirants, to attend the small classes designed to prepare us for our eventual research. Professor F. P. Wilson, a kind bulky rabbit of a man, instructed us in methods and sources of research for work in the literature of the English Renaissance (he was then at work on the volume covering a portion of that period in The Oxford History of English Literature). Helen Gardner was not yet Dame Helen and was thus a good deal less formidable than she’d eventually be. In addition to her huge lecture course, she led us B.Litt. aspirants through a meticulous class on the textual editing of poems of the same period. She was then involved in editing the poems of Donne, and we used her photostats of earlier editions and manuscripts—Xerox was a decade down the road—to make the difficult choices among numerous verbal candidates which would lead us to the poet’s intentions (the detective in me was steadily aroused).

Herbert Davis, an English scholar of eighteenth-century literature who’d also been president of Smith College, taught us how Renaissance books and broadsides were printed; and he eventually supervised our printing, on the Bodleian Library’s large old handpress, a small gathering of the poems we’d edited for Miss Gardner. Finally a likable man in Hertford College taught us to read, and even to write, many of the otherwise illegible handwritten scripts of the time (see Shakespeare’s signature on his will, for an instance of seventeenth-century illegibility).

Each of the classes was continuously interesting; and they offered the chance to begin an acquaintance with the few other students who hoped to pass a one-day exam, plus an oral, at the end of our second term. Success would either certify us to begin work on our theses or forbid our proceeding. Both Miss Gardner’s lectures on the Metaphysicals, in one of the booming lecture rooms of the enormous and icy Examination Schools, and Lord David’s small class in criticism—some fifteen students—which met in his slightly warmer rooms in New College were superb in almost startlingly different ways. I could see, when Lord David sat and raised his trouser legs a little, that he was the only Briton of my time whom I discovered as a wearer of men’s long underwear. Later I’d be wearing the same in the grimmer months.

Helen Gardner knew her subjects exhaustively and conveyed her mastery in lucid, but never condescending, lectures—one of the rarest of academic skills. She’d nonetheless been subjected to many of the disappointments of a brilliant woman in what was then distinctly a man’s world. Stephen Spender would eventually tell me that he’d heard from W. H. Auden that, when she held a job at the University of Birmingham, Gardner fell in love with the poet Henry Reed. Reed, however, was queer; and Gardner’s encounter with that reality led to a psychotic breakdown. In the absence of a good biography, I can’t vouch for Auden’s story; but it has a likely sound, especially since I slowly became aware of her reservations about many of her male colleagues at Oxford, and more than once I heard her cast strong aspersions at Auden and his friends. As her pupil, of course I was fascinated to hear of those possible early troubles in her life.

In any case her ferocious conviction of the rightness of her opinions and her thrusting ambition in a time when women were still not expected to possess such aims left her unpopular with many of her fellows in the English faculty. And I later learned from one of her more sympathetic colleagues—David Cecil—that “Helen is the only person I’ve known who went barking mad and then came back—partway at least.” Luckily I collided with none of her unlikable traits. On the contrary—after a well-earned knuckle-rapping, she always treated me warmly.

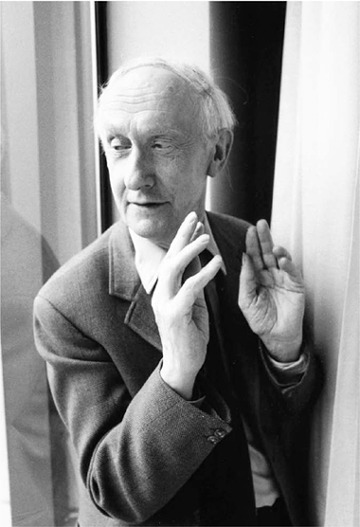

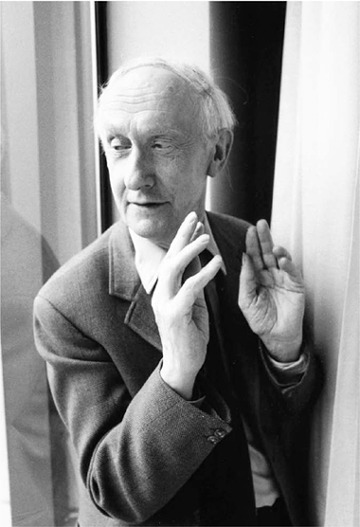

Lord David Cecil, photographed by my friend Thomas Victor when David visited the States in 1979. I flew to New York to see him, and spent a memorably bibulous and affectionate evening with him and his wife Rachel in the otherwise empty but opulent apartment of Mrs. Brooke Astor (she’d lent it to the Cecils for their New York stay). The next morning I phoned Tom Victor—than whom there’s been no better photographer of writers—and asked him to photograph David and, if possible, to catch his lordship in the unself-conscious midst of one of his most famous Oxford-lecture gestures—both hands upright in the air near his face, with the long fingers extended on the verge of stroking one another nervously. Luckily, Tom succeeded. Here David is seventy-seven years old, yet the picture clearly summons back the splendid talker who never treated me with anything less than unbroken kindness. Tom died of AIDS at far too young an age, and his best photographs have never been collected in a book.

It’s worth noting here that she then had no earned doctoral degree; but that was true of virtually all the best teachers with whom I worked at Oxford—again, British academics would generally receive an initial bachelor’s degree; then proceed to educate themselves thereafter, and brilliantly so in a good many cases. F. P. Wilson, David Cecil, Helen Gardner, and Nevill Coghill (among my early teachers) possessed a depth of knowledge and reflection which they wore with a grace, wit, and often elastic readiness to learn that was new to me. It’s been disturbing to learn, however (from the last book published by my eventual digs-mate Anthony Nuttall), that “when Dame Helen Gardner, famous for her academic ferocity, lay dying, she too was visited [as Richard III was in Shakespeare’s play] by the figures of those whose theses she had failed, whose careers she had marred; they stood round her bed.” Tony didn’t say where he’d learned of her deathbed trials (and now he too is dead); but he himself had been a student refused by Gardner, though his superbly successful career was hardly marred by her.

* * *

David Cecil, the critic and biographer of Lord Melbourne and Max Beerbohm (among numerous others), was the object of more affectionate and unskilled mimicry than any other member of the English faculty, of which he was now the most internationally noted member. The grandson of Lord Salisbury, Queen Victoria’s long-serving prime minister, and a descendant of William and Robert Cecil, who had served Elizabeth I and James I in similar offices, Lord David had more than a few justifications for self-confident oddities. And in fact he was notorious—in his well-attended lectures—for eccentricities of performance which may or may not have been intentional or neurologically required.

For example, he tended, in his frequent moments of genuine aesthetic excitement, to spray his nearby auditors with tiny drops of spittle. In even more powerful moments, he’d clamp his eyes shut and rise to his toes in an O altitudo! of appreciative ecstasy. Simultaneously the mile-long fingers of either hand might extend and wave round before him with what his delighted students called “Lord David’s porridge-stirring.” Even in calmer moments, his thumbs executed a ceaseless stroking rhythm on his second fingers—a habit which I sometimes find myself unconsciously imitating, even today.

However if a student troubled to approach him with a serious question—or to attend a term’s worth of one of his small classes and immerse in the texts he set for his weekly meetings—that student could come to know a senior scholar-critic of unfailingly keen intelligence, warmed with a generous admixture of kindness and an utterly personal humor. But lest I’ve suggested an excessive softness, I’ll add that he suffered no fool gladly, even the then-notorious Dr. F. R. Leavis of Cambridge, who’d often employed David Cecil as a foppish straw-man representative of all that was wrong in British literary studies. Yet if an apparent student-fool proved to be psychically disturbed, he’d find real compassion from Lord David. In the first term’s class, I saw him deal helpfully over several weeks with a genuine madman in our midst, one who seriously imagined that Princess Margaret was about to visit him.

Sad to say, a friend’s wit in conversation is the most fleeting of gifts. When the friend is gone, so is the humor, since it’s invariably a function of that person’s entire body in action (especially in so peculiar a body as Lord David’s and in however small a room). But in a lifetime’s acquaintance with several world-class talkers, I’ve known no other conversationalist who equaled David Cecil. And I stress the word conversationalist. He was most definitely not a monologist, and he took watchful care to avoid boring his company. He even once told me that his uncle Hugh Cecil had encountered a man who was famed as “the greatest bore in England.” After a long prologue the great bore paused and said “I hope I’m not boring you, Lord Hugh”; and the kindly Lord Hugh replied “Not yet.” The fact that David Cecil gradually became one of the greatly treasured friends of my life continues to be a source of real thanks for me.

As I’ve written these lines about him, I’ve returned to a fascinating volume of recollections—David Cecil edited by Hannah Cranborne, his great-niece by marriage. Reading the memories of such friends as Isaiah Berlin, John Bayley, Anthony Powell, and the old family retainer (third footman at one of the Cecil estates) who said of David “He wasn’t sporty and he didn’t like shooting,” I’ve found myself sad again to have lost such a man. In fact I can think of no adult friend—and almost no kin of my own, however beloved—whose physical presence and voice I miss more than David Cecil’s; thus hereafter I’ll mostly refer to him as David, which (early on) he asked me to do. In any case, his lordly status was a courtesy title, received as a son of the Marquess of Salisbury; and in those pre-Thatcher days, most of us enjoyed our work with an affable lord.

* * *

But in the midst of so many pleasures—such a rush of gladness—an unexpected darkness began to consume me. First, as October accumulated its shorter and shorter days, I was growing aware of my position on the planet. I was after all on a latitude with the start of unoccupied Labrador. By early November, full day wasn’t dawning on Merton College till about well past eight o’clock; a blue dusk was descending by four as the river mists rolled across the Meadow toward my window, and I had nearly two months to go before we reached the winter solstice—the year’s shortest day. That long ago very few of us knew anything about a now-familiar condition called SAD—seasonal affective disorder, a possibly severe psychic response triggered by hormonal change, to sunlight deprivation. Symptoms might range from mild depression to more serious derangements.

Among my many pleasures then, I was somehow growing sadder by the day. Something told me that I was responding—almost two years later—to my active role in Dad’s last weeks, the awful days after the removal of a lung in the hopes of surviving—for a few months or, at most, two years longer—the cancer he’d earned (at age fifty-four) for the smoking he’d joked about beginning in pre-adolescence. Mostly I’d served him as an efficient manager in critical situations; and as an elder son who’d never been called on for significant help, I took way too much pride in my final role. So it was months before I’d begun to feel at all troubled. I knew that I’d yet to undergo a full acknowledgment of Dad’s death; and I didn’t realize the inevitability of some such recognition. Was that what was gripping me now?

Whatever, one evening I returned to my rooms from a musical outing with a friend from New Zealand, Jeremy Commons; and as I stripped before donning my pajamas, I felt a small uneasiness in my left side, some five inches west of my navel. I explored the spot and soon discovered a firm lump, no bigger than a boy’s agate marble. The skin around it was not numb, but the shallow-buried lump seemed to lack all feeling. Was that a bad sign? Whatever, in an instant I was drenched in a downpour of certainty—cancer. My father had died of it twenty months ago, and now I’d join him.

Through the next two weeks, my mind increasingly sickened me; but I told no one. Who was there to tell? Among my new friends, no one yet seemed near enough to burden with the news. They were all my own age or younger; and if I needed anything just now—short of healing—it was wisdom. In those days only the wealthy could afford phone calls to the States (in the three years to come, I’d phone home one single time); and I wouldn’t want to alarm my mother with unconfirmed news.

After maybe ten days, during which I walked through my duties and a round of modest entertainments in near-zombie fashion, I went to Dr. Kirkham, the college physician whose office was a good distance across the city—near the almost disturbingly hideous Keble College, built (as it was) from an array of Victorian colored bricks, almost like some child’s entertainment. Kirkham patiently heard my complaint, examined me briskly, and told me that I had no cause for concern. This was plainly a small fatty tumor, he said, a lipoma—a collection of fat cells—and it might be reabsorbed as rapidly as it had formed. It would hardly grow further. I should ignore it and go about my life.

I recall telling myself a dumb joke as I walked back to Merton. Ignore it and go about my life—fat chance! The joke of course was no help at all. In the coming days—in an effort to calm myself (and with little thought that sheer work might serve me best of all)—I’d begin to indulge in one of the fine sidebars of Oxford life: plays and other theatrical events. My Rhodester friend Frank Sieverts organized at Balliol College a public reading of Tennessee Williams’s brand-new play, the deeply felt—and for those days, startlingly candid—Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; and I read the leading male role: the sexually and psychically tormented Brick. I didn’t feel then (and never would) a special affinity with Brick’s passive agonies, but Frank’s gentle demand for extensive rehearsals—and the large and enthusiastic audience who turned out for our single performance—gave me some relief.

* * *

The other immediate possibilities for diversion included productions available in the town itself. There were two professional venues—the New Theatre and the Oxford Playhouse—plus numerous college productions of all sorts. In London, only forty miles southeast and reachable by numerous trains per day, there were endless inexpensive shows. And at the end of a brief hitch-hike ride some forty miles northwest, there was Stratford-upon-Avon with its Shakespeare Memorial Theatre which—just a stone’s throw from either his birthplace or his tomb—provided a rich variety of first-rate actors in mostly fine productions of the work of the world’s ultimate Hometown Boy. In my first term I also went to what seemed a thousand films. Apart from the numerous cinemas in town, the Oxford Film Society offered screenings of classic films that had been past my reach in Raleigh or Durham, and Michael and I attended at least one such offering each week.

Then with Michael and another friend or two, I saw—at the New Theatre—an uncut pre-London production of Hamlet with Paul Scofield as the Prince and Diana Wynyard as his mother. After Laurence Olivier’s filmed Hamlet of the late 1940s, Scofield’s seemed excessively dry and monotone—a hard young man to care for, certainly not for the very long hours of an uncut performance; and though Wynyard was a glamorous Gertrude, Mary Ure’s Ophelia was a howling embarrassment. In Stratford I saw Anthony Quayle and Joyce Redman in a rollicking, if obvious Merry Wives of Windsor and then John Gielgud and Claire Bloom in King Lear. Though the sets and costumes for Lear by the Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi were too independent an attraction, the acting was unforgettably potent. Most impressive of all, in the midst of my descent into cancer fear, I saw the three most imposing Shakespeare productions of my life: Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier in Twelfth Night, Macbeth, and Titus Andronicus.

Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier as the murderous Macbeths in a production at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1955. I saw a performance with several Rhodester friends, and afterward we proceeded backstage for a meeting with Miss Leigh (Lady Olivier) who told us in amusing detail about a recent and loudly ballistic Guy Fawkes Night at the Oliviers’ home in the countryside. The two of them—near the end of their long and famous marriage—were appearing in a full season at Stratford—Macbeth, Twelfth Night, and Titus Andronicus. I’d eventually see their astonishing Titus three times but each of the other plays only once. It was a decade in which some critics felt that Leigh was exposing a smaller classical talent to dangerous comparisons by appearing with her titanic husband, whom she far surpassed as a film actor. Before the Stratford Macbeth, I’d seen the two of them together in New York in a superb Antony and Cleopatra where her Cleopatra was plainly superior to his underheated Antony (the same week, I saw their Caesar and Cleopatra). At Stratford, Olivier’s Macbeth was incomparable in its detailed portrait of a man slowly consumed by evil; but then Leigh’s smaller-scaled Lady Macbeth was a gorgeous viper who adored her husband and lured him into his murders by her sexual power over him. I’ve never seen better Shakespearean performances than the two of them delivered that fall at Stratford.

* * *

But with all the attempted distractions, my cancer worry continued till it had deepened into a real phobia, even the beginnings of a psychic breakdown. As the lump in my side seemed—to my probing fingers—to grow, I seriously thought of going to the one midtown travel agency and inquiring about the costs of shipping a corpse from Oxford to the States. As easily as I can imagine any reader’s laughing at the revelation, to me it still doesn’t seem a comic idea. The fact that I held off my inquiry was some sort of dawning realization that I was almost in deeper water than I could return from. I went back to the college doctor, and by then he perceived the gravity of my mental condition and sent me to a surgeon.

British surgeons are called Mister not Doctor, and I seem to recall that the fine man I visited in his offices in north Oxford was called Mr. Till. In any case, he patiently sat and heard me describe my recent history, then examined me, then sent me to the Radcliffe Infirmary for full X-ray studies. When he had the images in hand, he called me back to confirm what I’d already been told more than once—the X-rays had revealed a harmless fatty tumor. Since I’d told him of my accompanying stomach upsets, Mr. Till added a further interesting detail (in words to this effect)—“Mr. Price, I suspect that your gastric health may be complicated by your recent immersion in an English college diet. At the end of the war, we encountered a number of released prisoners of the Nazis who were suffering what we came to call carbohydrate shock. After months of sadly deprived rations, the sudden flood of potatoes, turnips, swedes, and bread swamped many of them with excess starch; and we had to warn them to limit their consumption, especially of potatoes” (at least two of those items were major components of virtually every Merton meal, and turnips had begun showing up only days before—swedes are what Americans call rutabagas). Having consoled me to that extent, Mr. Till then said that he’d like me to see a physician in Longwall Street—“Dr. Mallam, just a good internist to be sure everything else is in working order.”

I saw that elderly gentleman who examined me, stem to stern; then said that Mr. Till had mentioned my father’s recent death—would I tell him more about it? I recounted my role in those events, Dr. Mallam nodded and said “Well, of course you’ve been concerned.” Then he repeated the harmlessness of my tumor but said that, if I’d feel better about it, he could arrange with Mr. Till to have it removed—a simple procedure. With a kindly upraised hand, though, he stalled a prompt agreement from me and said that I should take a few days to think through the prospect, then let him know my decision. When he stood to see me out, he actually touched my shoulder—something no one had yet done in England—and he said “Mr. Price, if you have a cancer, I’m about to have a litter of puppies.” His rosy plump face grinned enormously, I suddenly burst out laughing, and my weeks’-long fear was dispelled on the spot.

On my way back to college, I stopped in at Corpus to see Jim Griffin. He and I had discussed the possibility of a joint trip to Italy during the upcoming Christmas holiday or vac, as it was called—each of us would be expected to clear out of our college rooms for most of the time—and I’d held him off while I contemplated my imminent death, though of course I didn’t give him that excuse for my delay. (The Oxford academic year basically consisted of three eight-week terms—Michaelmas, Hilary, and Trinity—interspersed by vacs of some six weeks, with a longer summer vac.) Now I could tell Jim about my misplaced worry and confirm that I hoped we could move ahead with Italian plans—the fact that we had no erotic interest whatever in one another was one of the firmest grounds of our friendship.

* * *

Our original interest in such a trip had been encouraged by one of the unique Britons whom I’d encountered—a woman named Pamela Redmayne. I’d first met her when she’d visited friends during my final semester at Duke and had taken me to lunch in Durham. At the time she seemed to be in her mid- to late fifties and was the epitome of what I took to be a certain kind of English maiden lady—tall, not quite handsome but physically imposing, given to a steady stream of talk about herself and her famous friends. The years would sadly prove that—despite the hospitality of her home in the Cotswold village of Burford—Pamela was given to mythomania, a form of narrative invention in which she placed herself at the center of many important events, often political events which she couldn’t have witnessed, much less engendered.

For a single example, she once told me (in words to this effect) “Yes, I well remember when I was in Russia midway through the war, Joe Stalin called me in, showed me a long ward of starving boys and girls and said ‘Miss Redmayne, I only have food for ten of these children. You alone can make the choice; which ones shall we save?’” I honestly don’t believe that I’ve misrepresented her story—or more precisely, my memory of her story. Whether the stories proceeded from a walled-off set of delusions about her past or a simple desire to entertain guests or to make her own quiet life seem more dramatic, I can’t say.

Still, she had many forms of thoughtfulness, none of which I’ve forgot. Operating from her narrow two-story cottage attached to a large farmhouse called Bartholomews on the high hill at the end of the Burford High Street beyond the church and the Windrush River—and surely with a small minimum of funds—she’d often invite six or eight Rhodes Scholars to board a bus early on an Oxford Sunday morning and make the fifteen-mile trip to Burford (with the usual young man’s lack of curiosity about his elders, I never asked her how she acquired her interest in Rhodesters). There by her omnipresent sitting-room fire, we’d toast ourselves with sherry and then eat an ample lunch of well-cooked and blessedly seasoned chicken with copious amounts of rice. Though not a subtle cook, Pamela claimed time at the Cordon Bleu school in Paris; and while most of her recipes seemed more nearly Spanish than French, they produced unfailingly likable results.

After lunch she was likely to produce a walking stick for each of us and lead us off on a thoroughly brisk two-mile walk down the hill to Burford’s superb church or along the line of the slender Windrush, barely more than a creek, where Queen Elizabeth I had been welcomed by the villagers nearly four centuries earlier. And for this hospitality, she asked nothing more from us than, perhaps, “Four of the best lettuces from the Open Market in Oxford” or that we up-end the full rain barrel by the front corner of her house. As dusk began to close in, she’d give us a quick cup of tea with one of her fresh scones and homemade quince jam; then imperiously shoo us on our way downhill for the last bus back to Oxford (we’d flag it down, in the dark, with our white handkerchiefs).

* * *

One of the favors she’d done for me and Jim Griffin was to provide the name and address of a pensione in Florence, almost every Englishman’s favorite Italian city. It was the Pensione Quisisana, right on the Arno, only a few yards from the Uffizi Gallery and the city’s central piazza. But our first term still had a couple of weeks to run; and freed as I now was from cancer, I was still oppressed by the darkness and the indoor chill as winter drew near. Each Mertonian had a single electric-coil heater to warm his two rooms; but given the size of my rooms and the river damp, switching on the heater was about as effective as lighting a match in a chilled gymnasium. My return to health was completed, though, by an increasing number of friends—from England, New Zealand, Holland, and the States. Michael Jordan, with his keen interest in American culture and his readiness to go with me to films, plays, and concerts had soon become what David Gilchrist (he of the “dressing gown” breakfast) called my sparring partner.

And I managed to do a good deal of the reading called for by Miss Gardner’s lectures, Lord David’s class, my several prep courses for the B.Litt. exam, and my ongoing love of Milton. During my freshman year at Duke, in a major’s introductory course, I’d come to love Paradise Lost for the Baroque complexity of language which it managed to combine with an ultimately paradoxical tenderness toward its hapless and all-too-fallible human stars, Adam and Eve in their perfect home—Eden. And here four years later in a dark and freezing Oxford, I had a just-sufficient supply of scholarly genes to power me through the necessary hours of reading in an underheated Bodleian Library and my own ancient rooms (though Milton attended Cambridge, he was known to have visited the university library in which I studied; his father was a native of Oxfordshire, and the poet married his teenaged first wife some three miles away).

* * *

Stronger still, however, and growing steadily was the hope to write my own fiction and poetry. Late in the first term, I conceived a story called “The Warrior Princess Ozimba.” If I could find time to write it, it would be my second attempt to enclose—and partially defuse—some of the lingering intensities of Dad’s dying in a well-controlled and compelling narrative. Less than a year before, I’d written—in the single writing class I ever took—a story called “A Chain of Love.” It dealt with a death like my father’s and the family ordeal which surrounded it, and it still needed work.

Nonetheless it seemed firm enough to stand alone—a story that centered on an imagined girl named Rosacoke Mustian (my first use of a character who’d appear in three later novels) and on Rosa’s sympathetic fascination with a family who accompany a dying husband and father across the hospital hallway from her own dying grandfather—such a country family were encamped with an old kinsman in a room near Dad’s, though I never spoke with them. In contrast, “The Warrior Princess Ozimba” would center on a young man’s assuming a duty of his father’s soon after that older man’s death—the delivery of a promised pair of tennis shoes to an old black woman who had worked for their family through many decades. Even while I read for hours in the work on which I might soon be examined by the English faculty, I thought obsessively about both my stories. The two—one nearly finished, the other not yet begun—had all but convinced me that I was not wholly wrong to head for a writer’s future.

Less than a year earlier, Eudora Welty had been invited to Duke by a committee from the Woman’s College. She delivered a lecture that would become her much-admired later essay “Place in Fiction”; and at the request of my teacher William Blackburn, she met with a small group of students and commented on their manuscript stories. At that point in my dreamy notion of a writer’s career, I’d finished a single very short story which I was prepared to show a writer of Welty’s distinction. It was called “Michael Egerton,” was no more than three thousand words long, and again it dealt with an emotional and ethical quandary I myself had experienced at the age of twelve in my only time as a summer camper.

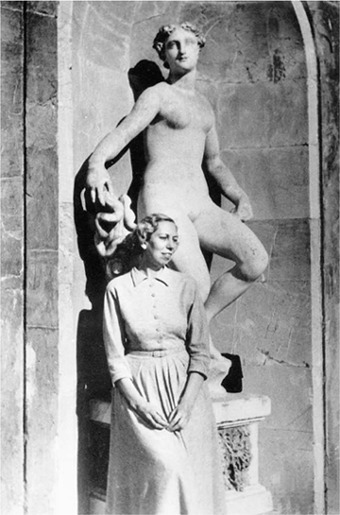

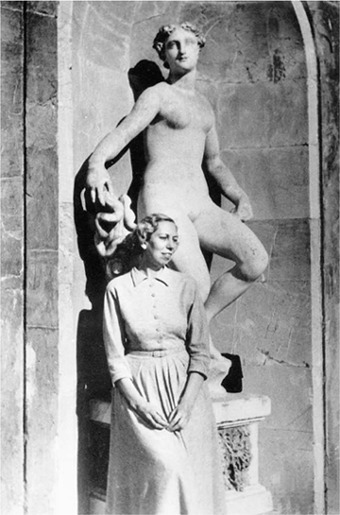

Eudora Welty on her first trip to Italy, probably in the fall of 1949. Not long after we met in 1955, at my request she sent me this picture and called it, in her accompanying letter, “Eudora of the Boboli.” She’s in the Boboli Gardens in Florence, and the picture is by Anthony Bower. Taken years before osteoporosis began to produce a slowly painful spinal curvature that stole seven inches off her height, she’s clearly a tall woman here, as she still was some five years later when I met her. Never a natural beauty, Eudora had nonetheless an overwhelming attentiveness and concern that left most people who met her with the sense of a beautiful nature. Uncoached, many—on their first meeting—remarked how much she was like Eleanor Roosevelt: devoid of surface attractions yet powerfully magnetic. Though I’d see her hereafter, time and again till near her death, I almost never saw her otherwise than elegant and lovely. She signed a picture of the two of us, taken in the mid-1980s, with these few words that move me deeply still—“Ours the best of friendships.”

At the end of her impromptu class—and in the presence of other students—Miss Welty told me that my story was thoroughly professional; might she show it to her agent? I was semi-pulverized with surprise, knowing that she’d actually published a handful of stories as good as the best of Chekhov. So I accepted her offer at once; and very shortly thereafter her agent—the superb Diarmuid Russell (pronounced DUR-mid)—contacted me, said that he thought “Michael Egerton” was “good,” and offered to circulate the story and any others that might be ready. At the time I was completing the first draft of the Rosacoke story, and I sent that on to him not long before heading to England.

He and I stayed in regular touch thereafter. Diarmuid’s extremely prompt letters had the quality of the e-mail whose invention was still decades off—a near-telegraphic speed, brevity, and pith. A cradle Irishman and the son of the mystic poet Æ (George Russell), Diarmuid had come to America as a young man but had maintained an ironic Irish view of Britain. One of his first letters to me at Oxford previewed his characteristic brand of brisk sympathy. He responded to my early complaint of insufficient indoor heating by informing me that the young Charles Darwin had encountered on Tierra del Fuego, while voyaging on the Beagle, indigenous folk sleeping naked (with no apparent discomfort) in the snow.

For all his salty attention, however, Diarmuid could not place any of my first finished stories—not quickly—and like so many apprentice writers, I spent more time in balked yearning than was good for my academic duties. When would my work reach even a small public of readers? I can even recall experiencing, on my straw bed, more than one dream in which I went to my pigeonhole in the Merton lodge and found—Yes! Letters of acceptance and actual checks.

So my first term’s work was more than a little compromised by all the uncertainties that surrounded my prime ambition to write and by the physical and psychic complexities that had surfaced in the wake of Dad’s death. I did, as I noted, see Mr. Leishman a second time in the term, though I recall nothing about the meeting. But the remainder of my degree work was accomplished in the B.Litt. classes and other public lectures. My chief memory of those weeks of work would have to be a partly delicious, partly melancholy sense of solitude as I’d walk the few hundred yards back to college from a long afternoon of reading in the Bodleian.

Once I dodged my way through the murderous traffic of the High, I’d duck down the narrow lane that led to Merton Street. Its modern name is Magpie Lane; but in medieval documents it’s a little startlingly but charmingly—and no doubt truthfully—called Gropecunt Lane (even in my time I’d occasionally come down the lane late on a weekend night and pass American airmen and English girls embracing upright against the old walls).

* * *

Apart from my two kinds of work then, and my growing friendship with Michael, I immersed increasingly in Merton’s distinctive social life. I’ve noted that there were a few other Americans in college; but I’d decided—on the voyage—that it would be absurd to stick with a group of American contemporaries when I had the chance, in what I assumed would be a two-year stay, to learn as much as possible about another country and its culture (one of my compatriots made it clear that he thought I’d made a wrong choice in adhering to the Brits—“none of whom will follow you home,” he said—but I ignored the warning, thank God).

I was soon joining, then, a small circle of English undergraduates in someone’s rooms to have coffee (weak powdered Nescafé) for forty-five minutes after a hall-lunch. I might then return from the library around 4:30 for a copious tea in the Junior Common Room bar with a few dozen student colleagues—most of us seated at minuscule tables, eating tomato or Marmite sandwiches while a skilled few of us threw darts with fierce concentration at a dartboard hung on a wall some eight feet away. At six I’d likely offer sherry to one or more friends in my rooms, or go to theirs for the same varieties of mostly South African sherry—a decent inexpensive version called Dry Fly was a frequent label. Then I’d put on my hip-length black gown (required for attendance at all lectures, college dinners, and other official events) and sit on a tightly packed wood bench to hear one of us read the college Latin (Christian) grace and then to bolt down in typical young-male fashion the dinner served over our shoulders by white-coated scouts.

As ever with institutional food, there was a fair amount of howling about its quality, though both the available British foodstuffs and the ambition of British cooks were still—as I’ve noted—overshadowed darkly by the Second War; the college meals were, I suspect, not a good deal worse than what many of my friends endured in their homes. First, there’d be a lumpy cream soup; then lamb, mutton, or sausage accompanied invariably by potatoes (fried, roasted, or mashed) and brussels sprouts, turnips, or cabbage; with a final pudding drowned under custard—all overcooked to stringy toughness or sodden tastelessness. Still, our vigorous table-talk proceeded, despite the fact that anyone could be sconced (compelled to drink a large tankard of beer without pausing to breathe) for talking “shop”—that is, discussing our studies. Our talk was, in fact, about little else.

Other dinner subjects were politics, sports, cinema, the telly, and Oxford characters (of whom there was always an ample supply). Oddly, in all my three years at Merton, I had no real friendship with another student in the entire university who was anticipating life as a novelist, poet, or dramatist; and I never felt the lack. In my second year, I met Willie Morris, a new Rhodester from Mississippi who’d eventually become a distinguished autobiographer. I enjoyed occasional meetings with him and his friends in New College, an all-American group that included the very bright and amusing Neil Rudenstine—a future president of Harvard—but Willie and I never grew close. His sense of rivalry was surprisingly strong; and it only relaxed in later years when (against his will) he left the editor’s chair at Harper’s magazine.

What I’d of course read about—but was finding it hard to judge this early, except as I developed an ear for accents—was the social revolution under way at Oxford and Cambridge (and to some degree in the “redbrick” provincial universities): the nation-altering results of the postwar Labour government’s decision to subsidize virtually any young man or woman who could succeed in passing through the strenuous obstacle courses set in their secondary-school educations. The colleges now—with a few exceptions, say, Christ Church and Trinity at Oxford—were no longer primarily haunts of the rich or the upper middle class; and what I was getting to know, for better or worse, was a whole new Britain.

The 1920s Oxford of, for instance, Evelyn Waugh’s novel Brideshead Revisited was meant to be dead. I say meant to be because, despite the presence of many “grammar school boys” at Merton—the sons of fathers who could never have afforded to send them on from secondary state schools to the university—many of my college friends came from well-to-do homes and spoke some version of upper-middle or upper-class British English (always the surest class identification test). At Merton there was even a small clutch of “Old Etonians” who spoke in the plummy tones that one seldom hears now, even in British plays and films.

In fact, I’ve now sat through numerous such performances in which native-born actors were supposed to be speaking in Oxbridge accents but could no longer produce a flawless simulacrum of those rounded vowels, produced at the very front of the upper row of teeth and then fed through the nose. There are even small errors in the accents of several otherwise fine performers in the brilliant televised production of Brideshead. I did occasionally reflect on the surviving chasm involved in our being served, both in our rooms and in hall, by men who were often as old as our fathers—many of them had defended the Empire in the recent war. As a native of the American South of course, being served by my elders was no strange phenomenon; but all those servants were black and the descendants of slaves, whereas in the Merton of the 1950s all the college servants were white.

In the face of such intentionally benign social engineering, I was still more than mildly concerned to encounter—more than once during my first year at Oxford, and a few more times in my British years—sudden outbursts of anti-Americanism from some otherwise friendly acquaintance. I’ve noted that Mr. Leishman was much given to commencing his cultural ventings with “Oh, you Americans.” Coming from his parodistic tweed-knickered frame, such moments came as no surprise and were the subjects of whatever comedy I could rouse on my return to college.

But from acquaintances of my own age and educational background, anti-Americanism came as more nearly a shock. In retrospect it’s also surprised me to recall that I was never challenged to explain or defend the particular evils of racial repression—and worse—in my own native province, the old Confederacy where, in those very years, the civil-rights movement was gathering speed and force. The complaints were always about American foreign policy, the continued extensive American military presence in Britain, and the bad taste in civilian clothing of American airmen on their boozy weekends in Oxford (possessed, as they seemed to be, of endless ready cash).

* * *

I was ready—perhaps too ready—to agree that the United States had plenty to be ashamed of, on the grounds of its own past (in the present world of George W. Bush we’re deplored, even hated, as never before in my lifetime). But to meet with such virulent expressions from a very few highly educated young Britons was to be amazed at their own refusal to acknowledge at least a pair of realities—both the long and oppressive imperialist history of their own country and a failure to consider that their resentment of the States might derive in part from their blindness to the fact that the quite incredible hegemony of their own small island nation in two and a half centuries of imperial world power had ended quite decisively, only a few years before my arrival in Oxford. A piece of real estate no larger than, say, that American region called New England had managed, through intelligence and luck, to rule a very large portion of the planet since the beginnings of the eighteenth century. Now it no longer did so.

The young protestors, however passionate and sincere (and some of them had only recently completed their required two years’ service in the British military), had a grave problem for their own personal futures. And it was a problem which they often seemed peculiarly unaware of. Since the old Britannia was effectively dead, there was no empire left to go out to, or to profit from, with the abstract skills for which their brilliant educations were preparing them. The thousands of jobs available to their forefathers were gone—and apparently forever.

I knew only one Mertonian from my three years who, on graduation, assumed an old-time Empire job—he went to Fiji to work in the postal system, I believe. What did these young men propose to do on the small and already crowded landmass of the United Kingdom? In all the hours of lively talk I heard at Merton, I literally never heard a word on the subject (but then I’ve never heard a word from a young American on the subject of our own inevitably shrinking empire). In any case, that first term ended at a peak of good cheer.

The crowning social event of the term was also its last—the college’s commemoration ball (what were we commemorating?). It was scheduled for the last night before we were due to scatter for the six-week Christmas vac. While spending an earlier weekend with Redmayne in Burford, I’d met an attractive young woman called Jill. She and her mother had taken me, on my first visit to Stratford, to see The Merry Wives. And eventually I invited Jill to be my date for the ball. She wrote back, accepted gracefully, and concluded by asking (in effect) “Shall I bring the Rolls? It might be fun for us.” I’m not sure I’d known that her family possessed a Rolls; but of course I said “By all means” (on my one visit to Jill’s home village, Swinbrook, Jill had driven me to see the Mitford family graves in the local churchyard—I had a curiosity then about the three remarkable Mitford sisters, primarily Unity who involved herself, perhaps romantically, with Hitler; then attempted suicide).

On the night in question, Jill drove herself from her Cotswold village into Merton Street where she parked an astonishingly well-tended antique Rolls by the college gate. What larks! as Joe Gargery says in Dickens’s Great Expectations. I can’t recall where we went for dinner—likely to the Café de Paris off the High or the Café Royale, two eateries by no means as grand as their names implied but as good as there was in the city then—or as good as Michael, our friend Garry Garrard, and I could afford for ourselves and our dates. Neither restaurant was more than a few blocks from college; but I’m sure we all packed into the Rolls and let Jill drive us there (none of us men yet possessed a British driver’s license).

Then back to college for dancing in the garlanded hall. Restored though it was, the medieval space retained its original lines and its noble volumes of timbered air overhead. Who provided the music, I don’t recall, nor precisely how we danced. Early in the evening there was a Scottish line dance, to bagpipe music, for the few Merton Scots, dashing in their kilts and sporrans. Afterward, it was mainly close dancing, with serious attention to proper footwork for the foxtrot, the waltz, or whatever else. By the time I’d left America, almost no one of my generation had mastered such steps; but stumbling though I was, I enjoyed myself.

The only small mishap was when, at our prior dinner—in the midst of inquiring about English dancing—I asked our assembled table “And do you also shag?” I was referring of course to the modified jitterbug which had originated in the Forties at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and then spread through the South. My friends took a gap-mouthed moment of silence, staring at their plates in a textbook illustration of the British idiom for sudden embarrassment, I didn’t know where to look. Then at last Michael said “Well, seldom on the actual dance floor.” It would later prove that shag was a British verb for “copulate”—only one of a number of idioms that divided our versions of the language in those days. The other great favorites were “What time shall I knock you up in the morning?” (meaning “wake you”) and “Keep your pecker up” (pecker meant “chin” in England).

We promptly recovered ourselves in gales of laughter. Though busily social, Merton was not especially famed for decadence; so I can’t recall that we drank ourselves into real inebriation. I do remember our taking pauses from the ball itself for quiet resorts to my nearby rooms where the six of us could talk awhile, but I think we stayed in possession of our wits. And at literal sunrise I saw Jill out to Merton Street and the Rolls which she’d drive back to her village.