6

A FEW DAYS LATER Jim and I flew north in sunlight, and that was very nearly the last sun I recall through the next two months. I was sorry to leave a city that I’d only begun to plumb. No lifetime could plumb it, especially given two enormous facts about the place—the fact that, in contrast to Florence, say, or London, so many of Rome’s fascinations lie out of doors, and in the further fact that so much of the present-day city exists in easily seen layers, from the oldest recovered prehistoric sites right on through republican and imperial times, through the Dark Ages of barbarian havoc on into the Renaissance, modern Fascism, and the ever-growing fringe of a contemporary metropolis. As our plane lifted off, I know I told myself I could live here, something I’ve never felt (before or since) about another large city.

Simultaneously, though, I was especially glad to return to England and my growing friendship with Michael Jordan. I’d thought about him a great deal in the past five weeks and had even received a letter from him—he’d delivered post-office packages in Brighton for a while before Christmas, then gone skiing in Austria. As far as the prospect of even colder rooms and a drastic shortage of daylight, I could tell myself that at least I’d been in Italy for the year’s shortest day. But January and February—even in the south side of England—were wet, dark, and cold. In those days of no central heating in Oxford (I literally knew no one who possessed it), my ancient rooms were heated only by the previously lamented single-bar electric heater. I’ve also noted that Merton provided us with a certain number of kilowatt-hours without extra charge (British electricity, being coal-produced, was phenomenally expensive then); but in the hope of something like an indoor fifty-degree level in the midwinter daytime, I employed my heater so relentlessly that my extra charges came, by the end of term, to a scandalous total.

My English student friends were indifferent to the problem. They thought nothing of warming the rooms to, say, forty degrees; then flinging their door wide open as they left for an errand and leaving it agape. My younger friend Anthony Nuttall, who’d later became a distinguished critic and teacher, used to tell our colleagues that “Reynolds is growing orchids over there in Mob Quad—orchids and iguanas.” He was rather proud of my Yankee extravagance. I seemed to be his tame billionaire. My prodigality kept me at least from perishing of cold, and I took a certain pleasure in being something of an outrageous college pet—the Man Who Craves Heat.

What any partial solution to my heating problem couldn’t help, of course, was my difficulty with darkness; and lamps which provided the required spectrum of daylight were decades off. So I battled a steady case of the blues—low-grade most of the time but by no means all. I was reaching an age, in my two parental families at least, where a man was expected to have a decent job and be carrying his own weight in the world, if not a wife’s and children’s also. And while I don’t recall seeing myself in that particular way, in retrospect I think that I did feel a considerable degree of shame.

The large amount of sheer pleasure I was taking in my life, the satisfactions of a lively reciprocated friendship with a Briton who had strong American interests, the enormous amount of dangerous spare time I had at my disposal, and the fact that a substantial gift of money from the Rhodes Trust was deposited in my name at Barclay’s Bank at the start of each term—all those things combined to cast an intermittent regretful air around me. I was doing fine—I made that clear in my letters home—but I did so with a troubling degree of wondering: were my letters to some degree sadistic, rubbing my pleasures into whatever wounds my mother and brother might still carry from Dad’s death?

Rereading my every-Sunday letters home after five decades, I can see that she and Bill were far from socketed in abject misery in Upper Dixie, awaiting me and my first paycheck. Mother had her consuming job, Bill had his high-school duties; but they had more friends than even I had, they had loving family, they were not—to my knowledge—in deep financial difficulties, and I thought I’d be home in eighteen months to widen any straits through which they might be moving (I’d eventually discover that Mother was concealing a few serious money troubles). To some extent then my guilt was excessive, but the degree of self-punishment was a gauge of the genuine care I felt for them.

Meanwhile I slogged on with my B.Litt.-prep classes, my choice of university lectures, and the patch of serious worry that bedeviled me when I thought of Mr. Leishman (if I visited him in January, I don’t recall the circumstances). But that one problem was soon dispelled. At the end of one of Helen Gardner’s lectures early in the term, I went forward to ask her a question about the day’s poetry. We talked for three minutes; then she glanced at her watch and said “Could we step across the street to the Eastgate and have a glass of sherry?” It was near lunchtime and the small Eastgate Hotel, with its pub, was only a few yards away.

* * *

In those days Miss Gardner was in her late forties; but her prematurely white hair and her bright, often smiling, eyes lent her head and face a real distinction. That, and the fact that she was already a renowned scholar in the small world of transatlantic literary studies, gave me an immediate sense of promotion to have this moment with her—a slight step-up in the then-minuscule world of the Oxford English faculty which, nonetheless, had my local fate in its hands. By the time our sherries arrived, we were launched on a discussion of the portrayal of evil in seventeenth-century English poetry—from the Macbeths to Milton’s Satan—and a mention of my unhappiness with Mr. Leishman had surfaced (not that I thought he was evil). Miss Gardner asked me a few slyly amused questions about his procedures. Then she sipped from her small glass—I’d soon learn that we were having what was called elevenses, a short drink and perhaps a biscuit (a dry cookie)—and she said “Would you like me to take you on?”

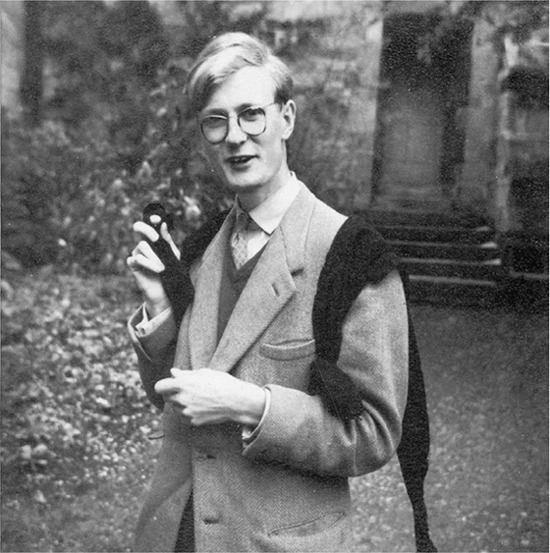

Helen Gardner, only a few years after she supervised my thesis on Milton. For a commercial photograph, it’s very much like the woman I knew, through so many hours of pleasant, yet probing—and surprisingly revealing—one-on-one conversation in two and a half years of work. Note the guarded reserve of the smile and the absence of vanity in her refusal to remove her glasses for the picture. The head is extraordinarily packed with information—facts combined with intense feeling. And that huge quantity is held by her with no false modesty; in fact, she’ll fight with all the strength of her small body for the rightness of her knowledge (her books and essays and the correspondence columns of The Times Literary Supplement sometimes scorchingly attest to the trait). As was often observed, she was not much loved by her colleagues; and many of her students approached her with fear, though my own experience was more enjoyable. Yet our relations never resulted in a lasting friendship. Apart from a two-minute encounter in our mutual bank on the High Street, soon after my return in 1961 for a fourth year in Oxford, I don’t recall that we ever met or corresponded again. As a man who’s now taught longer than she at our final meeting, I can well understand her subsequent silence toward me—I’d been one of her hundreds of students—but I regret my own silence toward a teacher who rescued me from early academic trouble and then bore patiently with my initial failures of academic focus. It seems that she died in misery. As a rigorous Christian, did she feel she was paying on debts she owed in a long life’s work? She owed me nothing whatever.

I’d been a mainly lucky man; but this degree of kindness from a distinguished teacher was surprising, though I’d revered most of my teachers. I’d attended Miss Gardner’s lectures for two terms and was a member of her seminar in textual editing, but this was the first time I’d sat down alone with her, so I leapt to say Yes. She made the arrangements promptly with no further requirement that I see Mr. Leishman, on whom I never laid eyes again. And soon I began to visit Miss Gardner in her almost unnaturally uncluttered rooms in St. Hilda’s to discuss a thesis subject (an old guilt at abandoning work with Leishman led me to include him, twenty-five years later, as a sympathetic minor character called Fleishman in my novel The Source of Light).

Since my sophomore year at Duke, Milton’s late verse play about the tragic Hebrew champion Samson had been my pick of all his work. The poet’s genius in the sheer manipulation of English (which he virtually reinvented for his purposes) had been the characteristic that first drew me to him, and in no other work is that genius more amply on view than in Samson. As Miss Gardner and I talked through our first meetings, it began to seem that my own interests and what she knew about prior work on the play—it was not then much studied—suggested a subject that might be most helpful to the world of scholarship: an exploration of Milton’s use of the Chorus in Samson. The play is far the most successful English-language attempt to write on the ancient Greek tragic model, and the Athenian dependence on a centrally important character called the Chorus (portrayed by fifteen men in the theatre) offers perhaps the greatest challenge to anyone working in the form, in whatever language.

We agreed on the nature of my early reading. It was going to be voluminous; and Miss Gardner was especially pleased with my suggestion of reading Italian Renaissance critics in their discussions of the Greek plays which were only beginning, in their time, to be published in anything resembling reliable editions (I felt ready to explore both Italian and Latin texts, with dictionaries handy). Soon I was keeping regular hours in both the upper reading room of the Bodleian and in its oldest wing, the fifteenth-century Duke Humfrey Library (built to house a donation of books from Humfrey, the brother of Henry V).

Otherwise I was continuing to prepare for the qualifying exam and went on attending lectures by Miss Gardner and David Cecil. I don’t recall in which order I heard them, but eventually I attended all David’s superb lectures on the early English novel and his full set of lectures on Shakespeare. I’ve never known another scholar with his particular gift for making a given work of fiction or poetry seem irresistible. Who would have thought anyone could take Samuel Richardson’s early seven-volume Clarissa and make it seem as riveting as a first-class film? More than once I’d left Lord David’s lecture, gone straight to Blackwell’s, and purchased a work he’d discussed that morning—in which process I discovered that Clarissa, for instance, is a very great, though extremely strange and lengthy, tragic novel.

* * *

My social life continued apace—considerably faster than was wise—and the numerous acquaintances I’d made in my first term had begun to winnow to a smaller group of close friends with whom I spent many good hours. Among my core of English friends was Ronald Tamplin, whose poetry and wit I much admired, and Tony Nuttall whom I’ve already noted. Tony’s own interest in exotic drama shone out one morning when he burst into my sitting room, fully attired in a suit of Japanese samurai armor which he’d suddenly discovered, inexplicably concealed in a cupboard in his rooms. For two minutes he gave me a hilarious imitation of samurai-movie grunts and lurches; then left as fast as he’d arrived (samurai films had only lately reached the West).

My close American college friend was the droll Iowan, Rex Jamison, with whom I made several more hitching trips to Stratford. Assorted others included Jeremy Commons, the New Zealander of what seemed invincible cheer and enthusiasm. He’d eventually return to his home country to teach and write about nineteenth-century Italian opera. Of younger vintages, I eventually located John Speaight, a textbook example of an English eccentric (though in his case the eccentricity was genuine, not manufactured for public entertainment). John’s immensely thin body, his high nasal voice, his returns to college from exploratory visits to the secondhand shops of the city with a string bag full of peculiar small attractions, and his fervent love of the voice of Maria Callas on early 78 records left an unshaken memory with me. And Peter Heap, though a different sort of man—a bass-voiced veteran of two years in the British Army—would likewise survive the years as an ongoing friend (he’d ultimately enter the British foreign service and conclude his career as ambassador to Brazil, prior to knighthood).

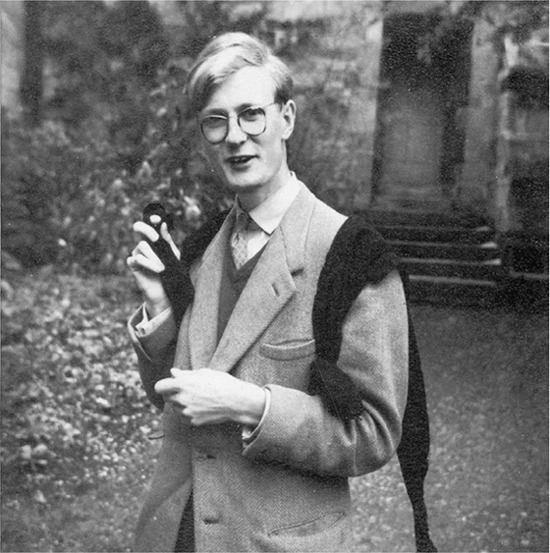

John Speaight, caught by me on the edge of the Merton garden in the winter of 1958. The odd black streamers down his shoulders are the draped remains of his Oxford Commoner’s gown, the gown that most of us were required to wear for any academic exercise—a tutorial, an exam, attendance at a university lecture, a college dinner, etc. Perhaps he was four or five years younger than I, but our shared interest in opera and drama gave us a good deal to talk about over tea in the afternoon or coffee after college lunch or dinner. John welcomed most chances to laugh and elicited much fun from his friends. Especially good were his long narratives of vacation trips to Soviet-era Bulgaria, where his father was British ambassador. Shortly after my return home in the summer of ’58, John turned up in Durham for a visit that took us as far south as Charleston. His unself-conscious eccentricity strengthened my liking for him as he returned to Britain to teach in several prep schools, and I much regret that I haven’t seen him for fifty years.

Michael Jordan remained the friend whose company I sought most often. Though he was deeply buried in his history studies, he seemed to find all my own interests welcome; and we continued meeting often for Indian meals in town (cheap and tasty, though one of our restaurants—the Cobra—got indicted for serving cat meat in one of the curries on its menu). After dinner we’d often go on to films, plays, concerts, and occasional train trips to London. Again, Michael was in the second year of his undergraduate work; but like most Mertonians he seemed to invest as much time as I in our eminently respectable, yet busy, nightlife. I’ve noted several other events that held our attention. Almost nothing, though, surpassed two of our London ventures—the Leicester Square premiere of James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause (the least good of his three films but still the most famous) and a single winter evening at Covent Garden. That would prove my only chance to see one of the supreme ballerinas as Margot Fonteyn and Michael Soames danced Prokofiev and Ashton’s full-length Cinderella. Ballet has never been a great pursuit of mine; but on this night, Fonteyn’s body performed unending miracles of grace that I’ve never seen matched by another human creature.

Despite Michael’s being two years younger, by the deep midst of the winter of ’56 he’d become a strong magnet for the loneliness that—in the face of so much pleasure—had steadily increased in my absence from home. One evening we were sitting up late in my rooms when I was overcome by nausea from a wretched college dinner—bitter calf’s liver and onions. Suddenly I was forced to race off to the equally awful Mob Quad bogs for the first of numerous attempts to empty my stomach. When I returned from the second attempt, I told Michael that my flashlight showed that I’d also retched up blood; and he quietly said that, with my permission, he’d like to sleep on my sofa just to be sure I made it satisfactorily through the night.

I was astonished at the offer, coming from so self-possessed and beautiful a man. I accepted gladly and again Michael’s value rose a long notch in my mind. I’ve noted my earlier sense of suspecting I loved him. More than any other man I’d known, he seemed to warrant such commitment—so long as my own offer could shape itself to the fact of his straightness; and his concern for my well-being on that one night almost surely is the fact that prevented my reviving the prior round of fatty-tumor cancer scare.

The memory of my bad-liver night reminds me of my favorite example of donnish undergraduate wit. Quite mysteriously one morning in my first year, white porcelain holders for toilet tissue appeared in the bogs, firmly screwed to the dark brown walls. Previously our “bog paper” had been flung about on the filthy floors—and good luck for finding usable pieces. British toilet paper of those years was frequently of an inexplicably dreadful quality—tiny sheets, slick as wax paper—and one wag was heard to say “Did you hear that old Westrate has broken his arm? Ah yes, slipped off the bog paper and hit the floor hard.” In any case, to memorialize the appearance of paper dispensers in the Mob Quad, the incomparable Henry Mayr-Harting wrote the following in the Junior Common Room suggestion book (and I quote from memory), “Let me record with surprise and gratitude the appearance this morning of porcelain tissue dispensers in the Mob Quad bogs. Let it not be forgot, however, that the French Revolution was, in part, hastened by a slight alleviation of the misery of the Fourth Estate” (that is, the commoners).

* * *

In the midst of the winter gloom, one of my efforts at lifting the horizon was the beginnings of an effort to purchase a car. When I was a freshman at Duke, my bachelor cousin Macon Thornton had given me $3,000 shortly before his death (the equivalent of some $22,600 in current funds). I’d banked it for long-term needs, and a car now seemed an urgent need. With Michael’s enthusiastic help then, I investigated the conceivable options. They quickly boiled down to two possibilities—first, a Morris Mini (manufactured in the Oxford suburb of Cowley but gimcrack in many details) and second, a Volkswagen. At that point in world history, I was still loath to invest in a German product—Hitler’s famous “People’s Car”—but the small VW Beetle seemed an affordable yet elegantly stubborn road hugger.

The price was initially daunting. At the Oxford dealership on the Plain in St. Clement’s Street, it would cost me $1,192—some $8,500 today. That would constitute a major bargain in new cars but a mammoth hole in my savings. In March of 1956, all the same—late in my second term—I ordered a new black Volkswagen with steering wheel on the left, American style (I intended to export it to the States at the end of my second year). I wouldn’t receive delivery till sometime in May—VWs were still scarce in Britain and imports were slow. However unpleasant the delay, it was just as well that I’d be firmly grounded in Oxford awhile longer—only four days after ordering the car, I sat for the B.Litt. qualifying exam.

Having studied ferociously in recent weeks, reading through the greater parts of most days in the Bodleian, I sat down in full academic regalia—cap, gown, and white bow tie—in one of the smaller rooms of the Exam Schools and endured the three-hour written portion of the exam (all questions centered on the period I’d chosen, the English Renaissance). That was soon followed by an oral conducted by four or five members of the English faculty. Both halves of the ordeal were based on the preparatory courses we’d taken in the past two terms, and they proved to be the most rigorous intellectual workout I’d experienced till then.

As I recall, seventeen of my fellow B.Litt. hopefuls stood for the testing. A letter to my mother reports that thirteen of us passed and could now proceed to the writing of a thesis, four of us failed. Two of the failures were non-Rhodester American acquaintances, and the sight of their collapsed faces as we clustered round the just-posted list of passes and fails was sad to say the least (no second chance would be offered them; the Oxford of those days was remorselessly realistic, and my friends’ single remaining chance was to leave the university). God knows what I’d have done had I failed.