7

PASS OR FAIL, throughout the second term, Michael and I had been planning to visit Italy during the Easter vac. He’d been there once before, though not to Rome. In any case the chance to go on the road with any close friend had always been high on my ladder of hopes, and this trip began only some two weeks after I passed the exam. Garry Garrard, our Merton friend from London, and a Brighton schoolmate of Michael’s named Ashley Basel were to join us for part of the trip. I’d only met Ashley briefly at a London party but I liked him. And Garry had been a cheerful friend in college, reading Arabic at the time and regaling us with his findings of the apparently endless sexual vocabulary of that language.

Before our departure, though, I had a week on my hands, unnecessarily idle. Instead of remaining in college and working away, I decided that—after the ordeal of my exam—I could hardly expect myself to continue to work uninterruptedly (clearly the remains of my American sense that college vacations were precisely that, vacations). In Britain then a Scottish noblewoman called Miss MacDonald of Sleat ran an organization that found vacation lodging for foreign students with no place to go. I applied for a week of such lodging; and Miss MacDonald found me an aged couple in rural Sussex who took me in. They were Mr. and Mrs. A. W. Street, and they lived near the town of Crowborough in Sussex.

Rather like tiny snow-haired dolls, both the Streets were well on in their late seventies, maybe older; Mr. Street had (I believe) once been chairman of the board at Lloyd’s of London, and their home was a large, calmly luxurious house surrounded by spacious gardens. There was no other guest but me, and I had a great deal of time in their silent house for reading and naps. Mrs. Street was still her own (rather scary) driver, and she took me off one day for a good view of the great house at Knole, the enormous ancient home of the Sackville family.

Otherwise we listened to a great many recordings of Mozart operas, and we ate especially well—they had a German cook. When I sat down for my first lunch, Mr. Street—a cheerful senior—asked what I’d drink with my meal. I asked for a glass of water; and he looked at me with amazement—“Water, Mr. Price?” I confirmed my request—“Haven’t you ever been thirsty, Mr. Street?” His face cleared slightly and he said “Well, I suppose I have, yes, frequently; but it never occurred to me to quench it with water.” So I drank water and he drank ale; in the evenings we all drank excellent wine. Brighton was not far away; and at the Streets’ urging, I invited Michael for lunch one day. He came by bus and assisted in cheering our willing hosts. At the end of the week, I left them with considerable affection for their kindness, took a bus into Brighton, and joined up with Michael for our journey.

Our budgets allowed us an only partial airborne trip. Before our early-morning flight to Geneva then, Michael and I spent the night in London in the digs of a Duke fraternity brother of mine who was then stationed at an American air-force base nearby. We arrived shortly before our friend and his fellow airmen were about to depart for their base; and the atmosphere of the flat, in its jollity, resembled that in the Pensione Nazionale on Christmas Eve—a likable mix of away-from-home Yanks (some of whom flew the bombers that were then in perpetual patrol, with their hydrogen bombs, above Cold War Europe) and their English girlfriends.

When the airmen and the girls finally left, Michael and I found some pub food down the road; then returned for an early night. When I turned back the covers on the bed I was to occupy, I was reminded again of the bed-linen realities of male college life in the States—the sheets were almost indescribably filthy—but my other choice was the chilly floor. Well, I was a mere child after all; so I took a deep breath, crawled into bed, and fell asleep in two minutes. Michael chose the sofa and the clock woke us well before dawn. We were due to meet Garry and Ashley at Heathrow at an ungodly hour.

We made our flight with Michael’s usual minimum of waiting time, then flew one more arc above the dazzling Alps and were in Geneva in time for a long walk round to acquaint the three of us with this odd combination of Calvinist grimness, international-organization world-optimism, and Swiss smugness (and that was before we knew the extent to which this scrubbed-clean country had financed a considerable portion of Hitler’s Holocaust). Then we found an inexpensive restaurant with superb fried potatoes and settled in for a clean night’s sleep at a pensione which Garry had found for us.

For some reason Garry and Ashley took an earlier train to Milan next morning, with the understanding that they’d find two cheap rooms to contain the four of us, get gallery tickets to whatever opera was scheduled for La Scala that night, then meet us on the steps of the cathedral at an assigned hour in the early evening. Michael and I rose in good time to find our way to the station and board a midmorning express train. Continental trains then always seemed considerably more crowded than the English; and finding seats in the packed compartments was one more challenge (everywhere, I was accompanied by my new but weighty leather luggage, a graduation present).

* * *

Still, Michael and I were standing on the steps of the cathedral at the promised dark hour. We waited a long while, long enough to watch a mysterious man box the perimeter of the large piazza at least a dozen times (could he have been fulfilling a religious vow?). He’d commenced another round when our friends appeared, breathlessly explaining their lateness, and rushed us to the highest balcony of La Scala just as the glamorous Herbert von Karajan, less than a decade from his denazification procedures, raised his baton and poised his famous profile for a performance of Richard Strauss’s Salome (Strauss’s own relations with the Nazis were hardly impeccable, but he did at least have a Jewish daughter-in-law whom he struggled to protect).

The greatest exponent of the outrageous leading role—the flame-haired Bulgarian Ljuba Welitsch—had sung her soprano to ribbons by then, and her successor Christel Goltz was no match for Welitsch’s demonic teenager with the ice-razor voice; but Karajan led a potent performance all the same, though the doings were rendered a little bizarre when it came time for Princess Salome to deliver the dance for her besotted stepfather King Herod. At that moment Goltz (who was neither unsightly nor obese) inexplicably slipped offstage as unobtrusively as she could manage; and the beautiful Russian ballerina Tamara Toumanova slid memorably into view to dance Salome’s crucial, and ultimately murderous, Dance of the Seven Veils to Strauss’s eminently and intentionally sleazy music.

A cheap supper followed the opera (all four of us had laser vision—before the invention of lasers—for good cheap food), then back to the hotel our friends had found. It proved considerably more expensive than I’d hoped, but the rooms were handsomely simple and clean. Tired as we should have been, Michael and I had the leftover energy to sit for hours more in our room and talk our friendship into a higher orbit; then a deep-drowned sleep. The room, incidentally, offered the only bidet I’d yet seen. I was embarrassed to reveal yet another layer of American naïveté; so I didn’t ask Michael for its purpose. I assumed it was a footbath.

Next morning we visited the remnant of the monastery where the shadows of Leonardo’s Last Supper were tantalizingly visible on the refectory wall above us. Leonardo’s almost pathologic ability to damage his paintings by radical experimentation with his pigments, and the fact that Napoleon’s soldiers would later cut a door through the foot of the mural, had severely damaged the dramatic focus—that moment when Jesus says to his twelve chosen companions “One of you will betray me.” Though I’d read Freud’s fascinating essay on Leonardo, as I stood near his ruined masterpiece I failed to reflect on the fact that a queer painter like Leonardo settled on such a potentially personal moment (a few years earlier, he’d been charged with homosexuality to the authorities in Florence and almost certainly arrested before he was finally, and inexplicably, released).

For all the ruinous state of the wall however, just being in the same room which Leonardo occupied for the long months he took to complete his work was exciting to a young man with my Romantic-era sense of human heroism—a sense I’ve never lost. I might never rise to such an enduring height, but I knew a precipitous peak when I saw one, and here was an unquestionable summit on a not-so-large wall just above me. Its richness was thus more comprehensible and usable as a goad to my own ambitions than Michelangelo’s titanic ceiling in Rome.

* * *

Then we headed for the station and off to Venice, arriving at dusk in the light rain that was to mark almost a whole Easter week in the Western world’s strangest city (Robert Benchley, on arrival, cabled his editor at The New Yorker, “Streets flooded. Please advise”). By water-bus we made our way to the university center whose existence I’d discovered in the Bodleian and were directed onward to a private home in which the center had reserved a spartan but clean room for the four of us with a toilet just down the hall, past the narrow cot on which a never-explained but friendly old woman slept. If any one of us stumbled past her in the night, she’d raise her head in the dark, grin, and say “Buona notte, signore.”

My memory of the next few days—my only visit to Venice—is discolored by the fact that I’d brought only my pair of leather loafers with me, and their soles began to separate from the uppers as I slogged through the cold early spring rain. With my tight budget I lacked sufficient funds to purchase a new pair of Italian shoes; and while a friendly cobbler made emergency repairs as I stood in his shop, they lasted no more than a day. I was back to the misery of sodden socks. Still, I recall the tedious grandeur of numerous Tintoretto walls, the riches of the Accademia (especially Giorgione’s ominous Tempest); and above all the golden dim interior of St. Mark’s cathedral.

On our first visit there, I encountered an unexpected presence. At the time I didn’t know what had brought him to Venice—I’d later learn that Stephen Spender was there for one more of his endless gatherings of writers from both sides of the Iron Curtain—but his shambling height and his striking large face were unmistakable. I’d seen him for an earlier moment in Oxford when a group of students brought him to the Café de Paris where I was eating. Spender’s repute is now undergoing an inevitable postmortem deflation, but in those days he was a much-respected figure in European and American literary circles and a powerful force in the literary cold war. Here in St. Mark’s he was wandering alone; and when he saw me and Michael across the incense fog of the cathedral—in our unmistakable Anglo-American attire—he nodded pleasantly.

That night we saw him again, coming toward us on a bridge and accompanied only by the frog-eyed, near-dwarf body of Jean-Paul Sartre. I recognized Sartre from the famous Cartier-Bresson photograph of his phenomenal ugliness, an ugliness that proved sexually irresistible to troops of women. Spender seemed two heads taller than Sartre, and his prematurely snow-white hair was unmistakable. They were chattering on in French; but by then Spender recognized us and paused for a second nodding instant as we passed. Even Sartre removed the pipe clutched in his teeth and gave a curt bow in our direction—the first and last time I’d ever see him, the most famous philosopher of the twentieth century looked to me like nothing so much as a Cyclops. His thick glasses gave his cocked eyes the quality of a single huge eye.

Again on a faster schedule than ours, Garry and Ashley departed Venice after two days. Ash was another man I’d never see again; a few years later, he was briefly imprisoned for manslaughter in a traffic death. Michael and I stayed on in the rain, largely because I’d invited one of my best friends from Raleigh to join us for Easter. While we waited, we saw a poster for a jazz concert that evening, to be given by the Jazz Club di Venezia. Given our mutual interest, and the seduction of the group’s name, we bought tickets and turned up in a smallish hall at the announced time—8:00 p.m. Silly lads. What we might have known by then was that announced times in Italian entertainment circles were highly approximate.

So we sat, patiently enough, as a young and well-dressed audience filtered in. Then the band materialized, man by man, on a brightly lit stage and indulged in a good deal of leisurely handshaking, embracing, and private but clearly enjoyable conversation among themselves. Finally, past 10:30 the music began—a likable and mostly original blend of Dixieland and more modern jazz. Eventually we realized that the main truth of the announcing poster was the word concert. There would be no dancing, no drinking, no cheering from the audience—pure music. So we listened till far past midnight, then quietly left as the band seemed ready to play till dawn. Tired as we were by then, we were young enough to remark before bed that we could at least return to college with a no-doubt-safe distinction—the only Mertonians who were likewise dues-paying members of the Jazz Club di Venezia (our ticket fee had enrolled us).

* * *

The Raleigh friend I’d invited to join us had a striking name—Jane Savage (Milton had written one of his college poems on the death of Jane Savage, the Marchioness of Winchester)—and as my friend’s father never ceased to tell me, their first direct Virginia forebear was Thomas Savage, a teenaged member of the original Jamestown colony of 1607, one who was given as a long-term hostage to Chief Powhatan (the father of Pocahontas) and who spent the remainder of his life in being an English settler, a fluent Algonquian-speaking friend of the local Indians, and the recipient of some nine thousand acres of Virginia land from one of his Indian friends.

Jane and I had shared a high-school romance that rapidly resolved into permanent friendship (we’d never repeated the soft-core petting of our early dates). At present she was working for Radio Free Europe in Munich and was rooming with a cheerful American named Liz McNelly. Driving an antique car, they were to reach us a day or so before Easter; and at last the sun broke out on Venice, just as I’d begun to start howling for light. Exactly as scheduled we met them under an unmarred sky in the main piazza; and once we’d exchanged introductions and embraces, the girls had a piece of news that couldn’t wait.

Through their job they’d just learned that Premier Khrushchev of the Soviet Union had delivered a secret speech—little more than a month ago—to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party in Moscow. Jane and Liz could tell us only the barest facts; but the CIA seemed to know that, in its usual enormous Soviet length, Khrushchev’s speech detailed in awful specificity the crimes of Stalin and his henchmen—it was as revolutionary a statement as anything ever said by Lenin. Standing there, cooed at by pigeons and pelted by sunlight, the four of us could barely begin to weigh the effects of such a revelation. So no doubt Michael and I nodded sagely, then suggested a coffee nearby. But the girls were staying at a slightly more upscale place across town and felt the need to unpack and wash.

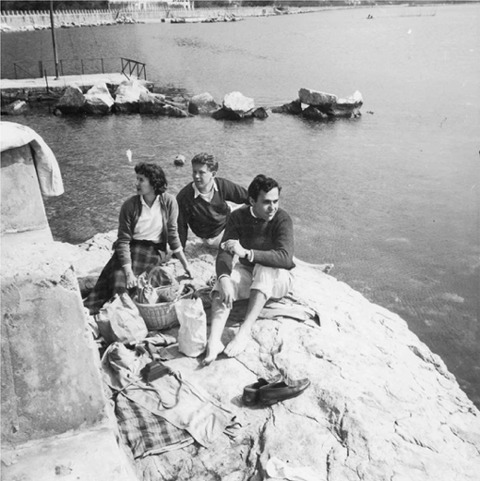

Liz McNelly, Michael Jordan, and I picnicking beside Duino Castle between Venice and Trieste during the Easter weekend of 1956. It had been a generally rain-soaked week, but the skies cleared beautifully for this day and the next (Liz and her roommate had driven down from their jobs in Munich for three days). When we began the day’s trip to Trieste in Liz’s rattletrap car, I had no idea we’d pause so near the birthplace of Rilke’s great Duino Elegies, among my favorite modern poems; but my poetic excitement in no way reduced my interest in our mortadella sandwiches and wine. My high-school friend Jane Savage—Liz’s roommate—is concealed behind my camera.

We gave them a generous hour and were then determined to share a few of our own discoveries while the sunlight lasted—a few of the potentially sinister corners of a tortuously complex town. Mainly though we sat over coffee at Florian’s in the piazza and then over drinks at Harry’s Bar, made bafflingly famous by Hemingway despite its cramped charmlessness. Throughout, Jane and Liz regaled us with hilarious stories of their lives as low-level employees of the small clannish group in Munich who appeared to run Radio Free Europe. They were convinced, years before the secret was public, that their network—which broadcast “the best of America in news, music, and the arts” to Iron Curtain countries—was a CIA-front organization and was by no means entirely supported by the donations which it sought in TV commercials back home.

On Easter Saturday we decided, for lack of a better plan, to drive east to Trieste. For insurance reasons the women did the driving; and the trip was my introduction to the hair-raising reality of Italian highways, even then. The distance was not more than a hundred miles, but it seemed to take forever (the engine emitted desperate noises at disturbing intervals). Shortly before our destination I saw a sign—DUINO. I’d known that the poet Rilke had received his first inspiration for the Duino Elegies when he was staying there in the winter of 1911–12 in a castle owned by the Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis-Hohenlohe. This had to be the spot.

In any case it was lunchtime, and with considerable relief I called for a detour. Jane took the right turn, we found a grocery, bought the makings of mortadella-and-cheese sandwiches and a liter of local wine, and paused by the Adriatic to eat our lunch in sight of Rilke’s castle—a heavyset fortress on cliffs that plunged to the Adriatic not more than a few hundred yards from our picnic. It had apparently started life as a Roman watchtower (that portion was in ruins); and Dante was supposed to have written parts of the Commedia in the early days there. We could see no signs of present movement, and no hope of entrance in those days; the castle is still owned by the Thurn und Taxis family. But the memory of that proximity only some forty years after Rilke’s great beginning—Who if I cried would hear me among the angelic orders? (and the snapshots I still have as proof)—remain mysteriously more potent for me than my visit to, say, Shakespeare’s tomb or the altar of Milton’s first marriage.

Trieste left almost nothing with me in the way of recollection, only the thought of a jubilantly manic guard at yet another sunlit castle in the city—a man who kept flapping his arms for us, crowing like a rooster, and calling Liz “una bomba atomica” with apparent reference to her striking good looks. We could only laugh and beat a slow retreat in late afternoon, back to our sick-sounding car and the hope of reaching Venice somehow before Easter dawn.

We made it before dark, with help from a rural crossroads mechanic between Trieste and our destination. He raised the hood, listened raptly to the awful sounds, made fifteen minutes’ worth of adjustments, smilingly refused any payment, and sent us on our way to what was then the one enormous parking lot on the outskirts of Venice (you left your car there, locked it hopefully, and walked across a bridge into town—streets flooded indeed). We splurged a little on a good dinner, had coffee on the piazza again, took as long a walk as our tired legs allowed, then headed to our separate lodgings for an early bedtime.

* * *

Being men of our time and place, Michael and I rose early next morning and dressed in jackets and ties for the occasion. Though neither of us was then a churchgoer, we reached the Piazza San Marco before our agreed-on meeting with Jane and Liz. So we waited for them near the main door of the cathedral, surrounded by the zillion pigeons who were plainly unwilling to believe our hands were empty on such a holy day. Then, as surprising as an unexpected gong-crash, a silent ecclesiastical procession rounded the corner to our right; and in its midst was the then-patriarch of Venice, Cardinal Roncalli.

In two more years he’d become the benign and astonishingly reform-minded Pope John XXIII, the convener of the Second Vatican Council which would change the church so irrevocably. Old, short, and agreeably stout, Angelo Roncalli—the son of tenant farmers—was physically a twin to my never-married cousin whose gift of money had bought the Volkswagen; and he passed within a few feet of Michael and me. Though neither of us had Catholic roots (not for the past four centuries at least), we were the only humans near at hand; and the cardinal gave us an especially generous blessing, smiling broadly.

He didn’t say to us what an Orthodox Greek or Russian priest might have said—Christ is risen!—but his cheer was evidence enough. All my life, from the age of seven at least, I’ve bowed to the significant historical evidence that Jesus actually rose from the dead in bodily form, not as a mere actor in the dreams of a few disciples. In chapter 15 of Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, he sets down what he’s learned (presumably from Jesus’ brother James and the prime disciples, Peter and John bar Zebedee, he records resurrection appearances to more than five hundred people). Of that small group, only another small handful can have moved onward—against enormous opposition from their own people and from Rome—to make, of their Lord’s teaching and personal transcendence, a religion that in under three centuries had conquered the empire itself. I gave Roncalli a grateful wave back then; and on he moved to say a high mass for Easter Day and to become, so soon, one of the world’s most powerful men—perhaps the most significant pope since the Renaissance.

* * *

Later in the day we saw Jane and Liz off back to Munich in their ruinous car—it actually made it—and next afternoon Michael and I took a train for Rome. The meeting of all four of us had been a big success. Michael and Liz clearly took to one another at once; Jane and I fit back together like the friends we’d been since the age of sixteen. There’d been no physical intimacy still; just the luxury of laughter and great ease in one another’s company. So I don’t think I’m entirely hallucinating when I mention here that I more than half remember writing to Jane later in the spring and, a little skittishly, suggesting that she and I might want to discuss the notion of marriage—how good an idea was it for her and me? I have no present memory of the thinking that lay behind my letter. But all these years later, I wonder if I’d gone weak-kneed about some aspect of my sexuality or the prospect of as solitary a life as I’d long foreseen myself leading? In fact, though, I think that my father’s death in ’54 had freed my mind to pursue its engrained course—a course that I still believe would not ultimately have disturbed that good man whose own life had no doubt reached into corners that he never had time to discuss with me before he was gone.

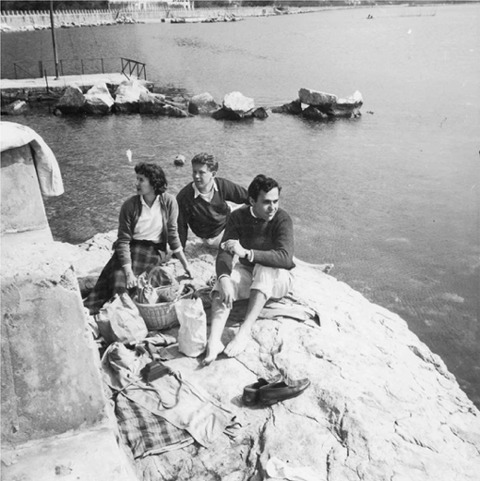

Ruins adjacent to the castle at Duino. The castle complex is built upon the ruins of a Roman fortress. After our picnic nearby we didn’t walk the few hundred yards from our lunch by the Adriatic toward the castle itself; but again I was especially struck by being so near the place where Rilke had begun work on his Duino Elegies, and I took this picture. My recent Christmas weeks in Rome had introduced me to actual antiquity—true ruins left over from the hands of human beings (back home, I’d been impressed by eighteenth-century buildings; and I did after all live in an Oxford quad begun in the fourteenth century)—but I can recall a certain thrill at spreading a picnic out on a rock in sight of something as old as this north-Italian ruin. The entirety is still in the hands of the Thurn und Taxis family, and the newer castle is open to the public.

Shortly after the next millennium, Jane died of multiple sclerosis in pain so enduring and intense that it drove her to near distraction (she spent all her nights paralyzed and in an otherwise empty house). A few years before her death, Jane told me that she still had all my letters. Whether they survive, I don’t know and haven’t tried to discover. I can’t then confirm the tone I took when writing to her more than fifty years ago. I’m certain, though, that she responded with the kind of good sense that characterized helpful stretches of our youth—no, marriage for us would surely not work. Her own eventual marriage—to a lawyer who moved her to a small conservative Carolina town—proved a failure, and she died in heartbroken loneliness.

* * *

Michael and I reached Rome to find that, incredibly, I’d made my second error in reservations there. Arriving just after dark, we went straight from the station to the student pensione whose address I’d somehow found. An enormous female proprietor met us at the door of the Pensione Università. Hearing our names, she told us at once that we were not expected till exactly a month from today. When I attempted to correct her, she produced my letter and showed me—inarguably—that I’d a made a simple but awful typing error and had reserved a room for thirty days hence. On Easter weekend—could Rome ever be more crowded?—I’d made that big a mistake.

Her face looked ferocious—what brand of fool was I? (when she wondered aloud if I was truly American, Michael broke down laughing). Still, given the hour, I tried at least to appeal to her Italian mercy. And when I confirmed my stunned disappointment and asked for her help with some solution, she melted a little. She’d have a room available in three more days; meanwhile we could sleep on cots in one of her hallways. But a large party of German tourists would rise before dawn for a trip to Pompeii (she whispered a reminder of the noisiness of Germans), and we’d be trying to sleep in their midst—a sufficiently awful prospect.

Earlier as we’d walked through the handsome postwar station, we’d been solicited by numerous men, loudly proclaiming the availability of inexpensive lodging. Now I suggested to Michael that we take a trolley back to the station and find a temporary room (the Milton was beyond Michael’s present means). He agreed, I begged the proprietress to save space for us three days hence, she offered an enveloping handshake and off we went. It was well past ten o’clock. The Pensione Nazionale, with its ribald Christmas memories, was only a few blocks away; but I didn’t suggest it. Still we quickly found a room in the Pensione Esedra, even nearer the station; and the flack carried our bags to the spot. The cost was daunting to us both, but I vowed to join Michael tomorrow in search of something cheaper till we could return to the Università.

Next morning we returned to the station. That early, there were no flacks in sight; but I happened to look down one aisle that ran off the enormous lobby and there—as I vaguely remembered from last night—was a sign that said, in Italian, “Society for the Protection of Catholic Youth.” I turned to Michael—“We’re Catholics, right?”—and led the way to a door beneath the sign. It was a small, severely unadorned room. To the right there was a long bench with two obviously pregnant girls, silent in their head scarves. They’d clearly come first, so we advanced to take a seat behind them. Suddenly, though, a woman’s voice called us; a young nun beckoned us toward her desk. I told her the true story of our debacle, she listened (smiling) and never asked if we were Catholic. Before I could say that we’d have a room in another few nights, she was writing an address on a card. She handed it to us and, when I asked what the room would cost, she waved a pleasantly dismissing hand (ah, Italy!). There’d be no charge.

Another trolley took us to the address—a boys’ boarding school, run by monks. The boys were away for Easter; and our room was what we might have expected—a bone-clean space, with two narrow beds (freshly made) and a crucifix centered on the wall. There was a running-water basin and a toilet with showers down the hall. A coffee-and-rolls breakfast was served, and for two days I don’t recall seeing another guest. Even the monks were mostly invisible—though if encountered, they’d bow and scuttle. And as we’d been told, when the time came to claim our space at the Pensione Università, we took up our bags and left. There wasn’t even a poor box by the door for a small contribution—something we just might have managed, given that our room at the Università cost $1.50 per night (including morning coffee, rolls, and jam but no more washing facilities than a basin in our room). We showered in a lower level of the grand train station, in the remarkably clean cubicles which proved to be rentable for showers—and whatever else was your choice.

* * *

The remainder of our time in Rome—was it ten days?—was much like my winter days with Jim, though the rain had mostly stopped. Among new sights I recall only seeing the older American film All Quiet on the Western Front—horrifically convincing (as it still is) in the portrayal of First War trench combat. At the prospect of our visit to the Vatican Museum, Michael quickly devised a new skill, one typical of his analytic mind. In those days the museum was arranged so that the Sistine was the final stop on your visit. Michael deduced that we should speed past the miles of ancient sculpture and paintings to the uncrowded Sistine, stay there as long as we liked, then amble back through the lesser collections. It was such a welcome discovery that we employed it on several other visits.

Again, the ceiling had not undergone the drastic cleaning which has left a spectacle whose colors look—in photographs—a good deal like early-twentieth-century French Fauve painting; so I’ve never felt deprived by my earlier experience of a reality filtered through the smoke of centuries. Any present visitor who regrets the experience of his elders should be assured that we saw a ceiling which amply attested to the genius of its creator and—for all its accretions—presented an entirely visible set of color compositions. In fact, The Last Judgment was far more beautiful before its cleaning.

And while the room’s crowded content has never comprised one of my favorite works of art, I’ve taken every chance to see it again—most recently in 1980 when a family friend, a monsignore in the Vatican, allowed me and another friend to enter through the main door of the Sistine and study the ceiling and the often-ignored side walls at unsurrounded leisure (he also led us into the generally closed small Pauline Chapel which contains Michelangelo’s final two frescoes—the conversion of Paul and the crucifixion of Peter; there we were literally face-to-face with the paintings, in easy touching distance, and the nearness was even more startling than I’d have guessed).

* * *

I’d alerted the Traxlers—Vieri and Nicoletta—to my planned return with Michael, and we spent a complicated Sunday with them. I don’t recall where we met, though I know I was embarrassed—aside their usual restrained sartorial splendor—by the fact that I’d had to discard my Venice-ruined loafers and buy the only shoes I could afford—white canvas sneakers bought in a shop in the station. My Christmas friends were tolerantly amused by my explanation; and as ready as before with a thoughtful venture for their visitors, they revealed a plan. They’d always wanted to explore a deserted village an hour from Rome.

We piled into two small Fiats, then made our way out through the rolling campagna to the few brick, tile, and stone remains of a village called Santa Maria in Galera (or Galeria). It stood on a bluff above the small river; and from what Vieri had heard, the inhabitants departed more than a century ago, scared off by a plague. Since the site has shown evidence of occupation from Etruscan times till the eighteenth century, the discouragement must have been severe. Very little had survived from the abandonment till the day of our visit, except for what seemed to be the church tower (and in 1980 when I hired a driver and found my way back, only by proceeding to the tiny piazza and questioning the most ancient of the nearby villagers for proper guidance, I discovered that even the tower had collapsed).

As we loaded up to return to the city, one of our two cars got stuck in a gulley; and the four men of the party piled out to the rescue—and the virtual end of my new sneakers. Soon we were under way but as we approached the outskirts of Rome at dusk, a child (who’d been hesitating on the left edge of the road) all but flung herself into our car. I was sitting by Vieri on the front seat, and I can clearly recall the sensation of feeling a body crushed beneath our wheels. Thank God, I was wrong. We piled out to find a scratched and howling girl, maybe five or six years old.

A small crowd of men and women from the neighborhood materialized, and I dreaded an ugly confrontation. They all looked remarkably poor; my friends clearly weren’t. But at once Vieri told the child’s father that he’d drive them to the nearest hospital to have the daughter checked carefully. The rest of us waited in our party’s second car; and in less than an hour, they’d returned—no broken bones, nothing worse than light scratches. Our eventual dinner was a little hungover from the strange afternoon—an hour’s eerie ramble through a cursed deserted village, then a frightening collision with a live human child (the affluent adults and the wretched child). We finished early and bade a farewell that I’ve never since repaired, though my Italian publisher did get Olga Millo to photograph me a decade later when I was in Rome again.

* * *

Otherwise this second Roman visit deepened my involvement with the deep-stacked city and its characteristically dignified and mostly helpful modern men and women. Surely there’s no other city in history, with the exception of Jerusalem, which has been ravaged by so many vicious invaders yet functioned so generously for so long. And it’s been among my privileges—not to speak of pleasures—to visit Rome some five more times in subsequent years, always uncovering more and more and always welcomed with their peculiar hospitable yet self-possessed gravity by whatever Romans I met, from a bruised street-child to the treasurer of the Vatican.

When we’d spent all the money we’d earmarked for Rome, Michael and I took the train north to Florence for two nights at a pensione Michael knew of there. We invested more hours in the Uffizi, the Baptistery, the Duomo, the Accademia, the Medici Chapel and palace, and the Piazza della Signoria; and I was further reminded of my satisfaction in accompanying Michael to galleries and other sites—he enjoyed beauty in the way I most admire and find it easiest to travel with, which is to say he loved it rather silently; it affected his actions, not his chatter. When we departed Florence, I left it for good—and all its treasures. I’ve noted earlier that my southern heart had never quite warmed to the city and its citizens; and whenever I’ve had the chance to revisit Italy, I’ve headed south (I should add that I regret my inability to join in the later American access to the pleasures of rural Tuscany).

One more jam-packed express train—we dossed down to sleep on the corridor floor—sped us back to Geneva for our flight to London, then on to Oxford again. For my academic health it had been far too rich a time away (no fiction writing either). But a shared pleasure in unexpected wonders—and my own growing readiness to invest in a friendship that was skewed on its bases and Michael’s own patience with the same reality—gave us each a lifelong relation with an unfailing friend: laughing, confiding, mutually supportive in all narrow straits, long decades without a single false move between us.