9

MICHAEL AND I drove slightly east to Glyndebourne and heard Mozart’s Idomeneo, my only visit to the famed musical shrine. The opera was seldom produced in those days; and the reliable resources of Glyndebourne—luxuriously cast and conducted operas in the grounds of a handsome country estate which the audience was free to roam during the long picnicking intermissions—went some way toward full pleasure (it was likewise a beautiful evening). The opera house of the time was small—the size Mozart had likely composed for—and decidedly plain in its décor, though the acoustics were superb and the music exalted.

Next I dashed some two hundred miles west to Plymouth to meet the ship of my Duke friend Deede Dort (I’d not yet reached the age when I could suggest that an able-bodied adult friend seek public transport). She and I sped back to Brighton, found her a hotel room on the seafront, and joined up with Michael for a jocular Sunday’s drive to Canterbury where we roamed the cathedral which preserves the site of the murder of Thomas Beckett, the later goal of centuries of pilgrimage. Then we pushed on to Hastings and the nearby Battle Abbey where William the Conqueror had landed in 1066, killing the Saxon King Harold on the spot and proceeding to alter the fate of England and all its eventual descending cultures—their law and social structures and above all, the nature of the English language (an Anglo-Saxon tongue which gradually became at least thirty percent French).

After two or three days of good undergraduate memories and half-sad laughter as we walked on the front, Deede flew on to Paris where she’d study painting for several years; and I could finally bring myself toward something that represented, at least, the quiet solitude I’d treasured since childhood and needed now more than I’d realized in the midst of the past year’s pleasures and struggles. That state of calm didn’t, however, bring me back to a working scholar’s desk. Instead I began a one-man drive westward to see a few things that had snagged in my mind during years of earnest reading and—earlier still—in my boyhood obsession with good King Arthur, his questing knights, and the Grail itself: their own mysterious gleaming aim.

* * *

In that first postwar devastated decade, with petrol prices phenomenally high by American standards, the roads were hardly crowded with privately owned cars. And few British roads were more than well-maintained but narrow two-lane concrete strips, going their remorselessly curving ways till—suddenly—there might be a mile or so of blessedly dead-straight progress. Such stretches sometimes proved to be laid on the tracks of ancient Roman roads (I recall hearing an old schoolmaster say that he’d once asked his boys why the Romans tended to build straight roads—for shorter distance obviously—but one boy eagerly raised his hand to say “So we Britons couldn’t ambush them round the bends”).

On most of my extended road trips, I couldn’t plan to average more than thirty miles an hour. As an unadjusted American on my first long drive then, I had a good deal to learn. First, there were the old roads themselves. An impatient driver like me met with numerous scary moments when a two-lane road, in a curvy stretch, would unexpectedly narrow to little more than one lane; and I’d round the next curve to find myself in near-collision with an unhurried farmer driving some piece of antique farm machinery on to his next field. And in rural areas, which included most of southern England then, the high banks were often topped with dense hedgerows that loomed immediately at the edge of the concrete with no forgiving shoulders and made passing another car impossible. So anyone hoping to survive a day’s travel, in body and mind, was soon compelled to learn a steady patience.

But soon the new tolerance became one more pleasure of the trip. Apart from guidebook-recommended sites, there were few of the obvious roadside stops to which an American and his bladder were accustomed—few petrol stations and absolutely no snack shops (even most Stateside highways were then devoid of franchise fast-food stops). The only chance of a small meal would be in a village tearoom, a good country pub (sandwiches and meat pies), or occasional uninspiring restaurants in towns. A man’s needs to pee were easily met with the kind of unembarrassed roadside pause that was demonstrated to us on our first night in England; a modest woman faced more serious problems.

A generally reliable pleasure of the road—ultimately one of the memorable joys of my British years—was the average Briton’s ready willingness to talk and chuckle with a traveling stranger. Within days of my arrival in the country, I was asking myself how the British Isles could have acquired their worldwide repute for frosty self-possession. If anything, I was having to employ courteous ways of disentangling myself from a talkative and hugely helpful man or woman whom I’d asked a simple question (and a Southerner was a trained employer of polite escapes).

In my first term David Cecil had asked me, during our first conversation after his seminar dispersed, how I was being treated—“Are the English being beastly to you?” When I assured him of the contrary, he said “Don’t let them mislead you now. When the English seem cold, it’s worth remembering that—frequently—they just don’t know you’re there. Call yourself to their notice, and I suspect you’ll prosper.” And so I had. In fact by the end of that first academic year, I was on the verge of a finding that would prove accurate for all my later experience of Britons, with normal exceptions, right into the mid-1990s—The British are slower to declare a friendship than Americans; but once declared, they’re nearly unshakable in their loyalty, far more so than the glad-handing but often fickle Yank. And not at all incidentally, I think David’s suggestion of blind self-absorption—as an analysis of British beastliness—is also an explanation for a large part of the human animal’s rudeness and chill in whatever nation.

* * *

I drove west through the Thomas Hardy country of Dorset—especially the county town of Dorchester, with its city museum that then contained Thomas Hardy’s reconstructed study. His novels had begun to interest me when I discovered Tess of the D’Urbervilles in high school. I’m sure that I didn’t realize then how deeply I’d been marked by the fact that so much of my childhood and early teens was spent in a distinctly flavored region—the endlessly complex biracial society that had grown up in the cotton-and-tobacco countryside of northeast North Carolina, with its unadorned rolling hills, thick pine woods, and broomstraw fields, its sunbaked villages, and small towns with handsome white timber and redbrick homes from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the incredibly enduring hovels of black men and women who were, at most, only one or two generations out of actual slavery. Some seven decades might have passed since abolition; yet most of those men and women were still implicated in a dense involvement with their white overlords—an involvement that was, more often than we now acknowledge, as emotionally interdependent as the ruthless system allowed and had produced one of the twentieth century’s great Anglo-African languages and the verbal and musical art that was still arising from it.

Though Hardy’s world looked—to me, at first—far bleaker than my own, it had reflected in his novels an emotional complexity so much like the country of my early youth that it drew me powerfully in. And the fact that David Cecil was one of Hardy’s distinguished interpreters and an enthusiastic guide to my reading and English travels was a help (David’s father—and eventually his elder brother—were, in succession, the Marquess of Salisbury and were thus centered on an important Hardy town; and David himself kept a village home in the region almost all his life and died there).

* * *

I pushed on to Exeter with its fine small cathedral, much damaged by a German bomb; then on across the wide gloom of Dartmoor with—in the visible distance—its looming prison (you were warned then, as you still are in parts of the American southwest, not to run out of fuel in the area); and thence to Cornwall. My target was Tintagel and the ruins of its storied castle, and I reached the nearby village at dusk. There were virtually no tourists—to be sure, I dignified myself as a traveler—but there was a sad rash of Guinevere Tea Rooms and Lancelot Tobacconists. No motels of course and, according to the AA motoring guide, no hotel I could afford; so I entered a shop and asked if there was a local woman who could offer me an inexpensive room for a few nights. The female person at the counter took a long look at my face, then laughed, and addressed me in a thick Cornish accent—“You said a woman, didn’t you now? Well, if it’s a lady you’re looking for, I could send you on to Mrs. Mason. She and her daughter Jill are just up the road. They can likely take you in.”

A stubby woman almost swallowed up in her apron, Mrs. Mason and her antique suspicious spaniel welcomed me to the back bedroom—for a shockingly small sum—and in no time she and Jill, a pretty girl a year or so older than I, cooked me what they called “a meat tea”—four elegantly fried eggs, big rashers of Cornish bacon, bread and dripping (bread fried deliciously in bacon fat) followed by an eventual assortment of scones, cakes, and biscuits, accompanied throughout by cups of black tea strong enough to ream a radiator—and I was expected to eat their hearty dinner a little while later. In my three good days with the Masons, I spent so much interesting time talking with the two ladies in their kitchen that I finally had to force myself out into the gray drizzle to explore the ruins of my original magnet, the twelfth-century castle on Tintagel Head.

By what may be a complicated set of misunderstandings, the haunting landscape of the area, the masses of mossy stonework high above the crashing sea, an occasional now-empty grave chiseled into the live rock, and the one old church on the misty cliffs have conspired to win for themselves credit as the birthplace of King Arthur and, in some accounts, the site of Camelot itself. I’d read that much, often enough, in my childhood. And though I came here as a man disillusioned by his readings in the recent cold realism of Arthurian history, I nonetheless spent rapt hours roaming the otherwise empty array of this old place in simple awareness of visiting the same kinds of layer-on-layer of human habitation that had won me in Rome (there were fewer layers in Tintagel of course, but they were sonorous all the same).

Back at the Masons’ alone in my small room, I turned for the first time in months to serious thought about my fiction. I’d brought with me copies of the three finished short stories which I’d sent off to Diarmuid Russell. I’d also brought what I’d so far written on the story I’d begun in Florence but had got nowhere near completing in the six months since—“The Anniversary.” And more in hope than certainty, I’d brought my Florentine Olivetti. I can even remember some typing in Mrs. Mason’s kitchen, though I no longer know whether it was new work or the endless recopying to which all writing veterans of the pre-Xerox/pre-computer era were sentenced by the turtle-slow technology of the time—the laborious retyping of all new drafts and a constant reliance on the dreaded carbon paper if copies were needed. A further writer’s demon of the time was the never-quite-allayed terror of a lost manuscript. No writer I knew, once he revised a draft, ever corrected his carbons; so all our work was subject to fire, robbery, or the brand of agony that Hemingway endured when his first wife lost forever the only manuscript of his first book of stories (Lawrence of Arabia also lost his original version of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom while changing trains in Reading, England—very near Oxford).

* * *

I’d meant, intently, to concentrate on my two kinds of writing that summer—“The Anniversary” and then a very substantial amount of work on my thesis, on which (despite the promise to Miss Gardner) I’d managed very little, if any, work. The familiar yet incurable guilt of the seasoned procrastinator seldom ceased assailing the lone hours of my wanderings; but I consoled myself with the would-be writer’s assurance—relax, this is all invaluable experience. So after a glimpse at a few more Cornish sites with Arthurian overtones (above all, the ruins of King Mark’s castle, as in Tristan und Isolde), I made a slow way back from Cornwall for a few more days with Michael and his mother. Michael had a brief summer job, to help with the expenses of our forthcoming jaunt; but somehow it didn’t prevent our driving the hour north to Wimbledon where, according to a letter to Mother that week, we stood “for some eight hours to see Ham play.”

Hamilton Richardson, as I’ve noted earlier, was my Rhodester friend and was then a serious hope of American tennis. He was the top-ranked American player that year and might well eventually have won the singles at Wimbledon had his diabetes not stood in the way. Still, Michael and I were at Wimbledon for at least two days in June, unreserved but patiently waiting in line for access to the free seats. Though the sunlight was the most relentless I recall from that era, and with all our standing up, Wimbledon was a decided pleasure, however eccentric—the tents serving strawberries and cream, the members of the royal family in attendance in Centre Court to see the startlingly handsome Lew Hoad win the men’s singles (the finest eyes I recall on a man); and finally, the grotesque hats on would-be-fashionable Englishwomen.

* * *

I’ve mentioned that foreign students at British universities then had a real problem during the lengthy college vacs—where to stay. I’d moved out of Merton in June; and while I’d booked my Headington digs, the Kirkbys hadn’t agreed to take me in during any portion of the Long Vac. But I didn’t feel I should crowd Michael and his mother in their two-bedroom apartment for more than a weekend at a time. I could likely have offered Pamela significant help with the groceries, the grass, and the rain barrel for significant stretches in Burford; that prospect didn’t attract me, though. Yet whenever I contemplated renting a temporary room in Oxford, I’d look at my budget for the pending continental trip and realize how close to the financial line I was steering. For the first time in my life, I was all but adrift.

So I took the chance to spend a free week, in a Hampstead hotel, with my last Duke mentor William Blackburn, who was at work in the British Museum’s library on an edition of a particularly rich correspondence between Joseph Conrad and the editor of Blackwood’s Magazine. Blackburn had taught me Elizabethan and Jacobean poetry and drama in my sophomore year; and when I’d survived a stunningly low grade on the first paper I wrote for him, he invited me to lunch and, over a plate of barbecue, asked whether I’d yet considered applying for a Rhodes scholarship in my senior year (he’d been a Rhodester from South Carolina in the 1920s). To that point, I had no such plans; but Blackburn set the thought at work in me.

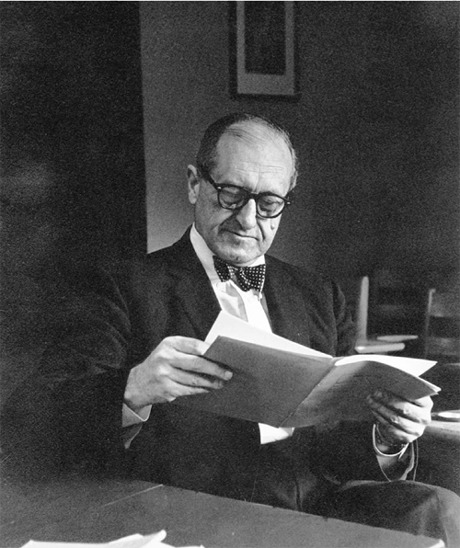

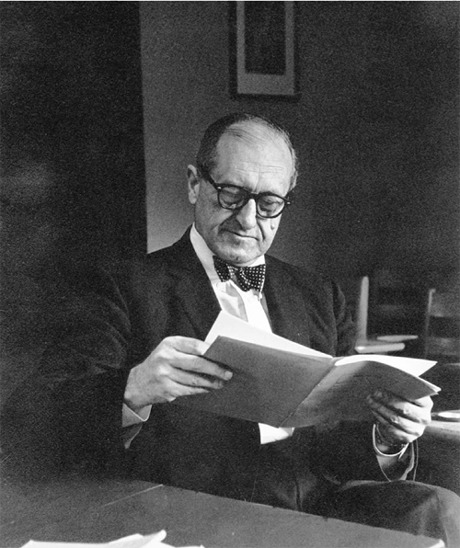

William Blackburn in 1961, in his longtime office on the second story of the East Duke Building of Duke’s East Campus. For some twenty years this enduringly successful but endlessly difficult teacher met his seventeenth-century literature class as well as his narrative-writing class in this small room. The few members of these deeply affecting classes sat in desk chairs along three sides of the office; Blackburn sat at his desk against the back window, with a view of the seated statue of Washington Duke just behind him. (The myth, in my student years, was that if a virgin walked in front of the bronze Mr. Duke, he’d be compelled to stand; very few girls took the risk. Nowadays no one even seems to recall the myth, much less fears risking a revelation of her sexual adventures.) Taken by John Menapace, who was then the art designer at Duke University Press and a photographer of real power, the picture is a forceful memory of Blackburn’s large head, nose, and hands. Even now, more than fifty years since my last class with him, I note with some degree of jitters that he’s reading one of the booklets in which we then submitted our final exams. If he looks up now, he’ll either grind his teeth in the deep despair of a lifelong teacher or break into his rolling bass laugh—a sign of rare pleasure from a troubled man.

Furthermore his classroom demonstrations of the degree to which a thoroughly robust man could respond to the power of lyric verse at its pinnacles—Thomas Wyatt, Walter Raleigh, Spenser, Marlowe, Shakespeare—were crucial to my own already strong hope to write and teach. It may sound Mr. Chips–like; but many more of his students than I (Styron among them) attest to the fact that William Blackburn was the kind of magus who could give his class an oral performance of, say, Spenser’s “Epithalamium” in his richly modulated baritone—sometimes accompanied by his own silent tears—and teach us more about Spenser, and poetry as a benign life force, than any number of lectures.

In my last year at Duke, his pioneering two-semester course in the writing of prose narrative—which he refused, admirably, to call creative writing (“All good writing is creative,” he’d say)—became the forum of my first two successful short stories. Blackburn himself could scarcely write a postcard. His own prose was stamped by the hulking awkwardness of his tall stout body. But he had the born teacher’s gift for identifying ability and authentic passion in a student and for zeroing in on those incipient qualities to produce ultimate results.

That very rare strength helped propel more than one man to the eventual publication of good fiction—William Styron and Fred Chappell were two of his other successful writers. He seldom encouraged female students, on the grounds that they were so seldom able—in their careers as 1950s wives and mothers—to find the time to write. In retrospect, while his explanation had a certain validity, my guess is that he more likely feared some romantic involvement (on his part) with a gifted young woman.

The fervor he was capable of pouring into his support of a particular male student—and his ability to reject fervently the same student if some never-declared, and apparently paranoid, limit were passed—eventually suggested to me, through a sometimes mysteriously interrupted friendship of more than twenty years, that there might be a deeply buried but troublesome erotic component in a few of his teacher-student relations. I recall for instance that he once spent almost an entire class hour demonstrating to us—very dubiously, to say the least—that Shakespeare’s most indubitably homoerotic sonnets could not in fact be homoerotic.

But none of the three other male recipients of his backing has ever mentioned to me any moment of overt word or gesture. On the contrary, so controlled was his support of me that after my father’s death in the winter of 1954, Blackburn became for me not only a respected teacher but—for almost a decade thereafter—a surrogate father (so much so that I ultimately regretted, in silence, giving him a handsome sport jacket that my father had bought a few months before his death; it fit Blackburn perfectly and gave him, at times, an unnerving resemblance to Dad).

I was glad then to spend those inexpensive summer days with him in London. By that point he was an enormously lonely man in his late fifties. He’d ended his own first marriage in the late 1940s; and despite often comically desperate efforts, he failed to find a second wife for another twenty years. In that time he was isolated from his teaching colleagues by what they perceived as a degree of paranoia that only grew more disabling as he aged. Even with his few adult friends and favored students then, he could often be grim company. He once told me that his father “died in a madhouse”—an assertion I’ve been unable to confirm. So perhaps he was burdened by a genetic tendency to severe melancholia. Yet despite his depressions, and his suspicions of the loyalty of even the most devoted friends, he worked with gargantuan energy at his teaching. And his often sardonic but irresistible wit could make him a frequently rewarding companion (weeks after our time in London, he spoke in a letter of “our week of laughter at the Sandringham [Hotel]” as the high spot of his English summer).

Of our time together, I recall mainly a continuation of the sunlit weather I’d had at Wimbledon and the chance to make some return on Blackburn’s many prior generosities to me—it would be years before he accepted my addressing him as “Bill.” On the night of July 1, 1956, for instance, I treated him to a genuinely first-rate musical occasion. At the almost-new Festival Hall, we heard the Verdi Requiem conducted by Guido Cantelli, a superb young Italian conductor. Toscanini’s much-loved protégé, Cantelli would be killed in a plane crash a few months later. On this warm and tranquil night on the south bank of the calm Thames, though, he led the Philharmonia Orchestra with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Ebe Stignani, Ferruccio Tagliavini, and Giuseppe Modesti in a performance of blazing splendor.

Blackburn’s love of music was one of the chief consolations of his solitude, but his taste ran—as it did in his choice of poetry—toward the leaner textures of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italian and English composers (secular ones above all). Yet for all his love of early music, and his general avoidance of opera, even Blackburn was demonstrably moved by Verdi’s mammoth eloquence in a Requiem which unflinchingly confronts the worst possibilities of death and remains bowed but upright and still rapt in the face of life’s final mystery, imploring God’s mercy on those who’ve preceded us beyond the veil of eternity. Only some eighteen months after my father’s death, the performance worked as a sovereign final distancing of that powerful man from my own grieving mind.