10

SOON THEREAFTER Michael and I—with the fledging beards we’d just begun growing—loaded my car’s tiny front-end trunk with our travel provisions (engines in VWs then were located in the rear): a minimum of clothes, and a case of canned corned beef that Michael’s mother had bought us, wholesale, for roadside lunches. Then we aimed ourselves due north. We spent a night above a quiet pub in the town of York (where Constantine was proclaimed Roman emperor in A.D. 306 and Auden was born in 1907); then a morning in the nearby York Minster. It remains to this day the grandest ecclesiastical building I’ve seen, the one that stands for me as a thoroughly convincing demonstration of the overwhelming reality, somewhere beyond us, of a watchful creative existence—something called God in the absence of some deeper comprehension.

Later that day we spent an hour in another grand building, tall above a river—Durham Cathedral, even older than York in its present form, with piers down both sides of the dim nave, massive in girth as the magnified legs of the Norman builders who set them up (I was mainly drawn to the bizarre face on the main door’s knocker, a place of safe harbor for runaway convicts). Then we pushed on for a night and a day with our beautiful Oxford friend, Stella Kirk from St. Hilda’s. She led us on a visit almost to the Scottish border to see Alnwick Castle, the home of the Percys and their rowdy son Hotspur (clearly one of Shakespeare’s favorite characters); then a roam through the ruins of Dunstanburgh Castle, the seat of John of Gaunt (gifted also with Shakespearean eloquence).

Then on to Stella’s welcoming family in the village of Felton, a few miles from our port, and a happy evening which included my introduction to cold poached salmon with fresh mayonnaise as a dinner dish, all at a big table with family and friends in the clear late light of a far-northern country—a further blessing poured round us. Next morning—July 12—Michael and I stood in Newcastle in further unblemished sunlight and watched my Volkswagen hoisted off the pier, straight upward through what seemed an infinity of dangerous air, then safely down aboard our ship for the calm all-day and overnight voyage across the North Sea to Norway: five hundred miles north, beyond the undersea Viking Bank.

* * *

Then the long-planned journey and our first week in Scandinavia. We claimed the unscratched car in sunbathed Bergen—which seemed a glistening toy town, the birthplace of the composer Edvard Grieg, though we hardly paused—and began our drive toward Oslo. Again it was little more than a decade since Western Europe had been freed from a state almost unimaginable to an American—the long grip of the Nazis and the worst of all wars that destroyed them. Norway reflected that recent history in many ways. Most striking at once was the fact that the roads, except in a few towns, were still dirt roads—well maintained but unpaved.

And there were few towns along the way—and over the mountains—from Bergen to Oslo, only the occasional village with, often, small squads of boys who seemed to be collecting license-plate numbers from the scarce traffic (as British boys then often collected locomotive numbers). My plate was QG-2166, as I well recall—largely because I can still hear the raucous young voices shout it out in Norwegian as we passed, waving their wild enthusiasm while we vanished eastward in a light cloud of dust. And almost anywhere we stopped—for gas or water—there’d be a single striking framed photo on the wall: a young man accepting the surrender of an imposingly uniformed Nazi officer.

The young man in the picture appeared to be in his early adolescence, and he seemed to be dressed in something like a Boy Scout uniform. I can’t recall that we ever got an authoritative explanation of the widespread scene, but a friendly drunk outside the Oslo city hall one later evening told us that the Norwegian government-in-exile had decided upon this moment as a final humiliation for its defeated enemy—the forced surrender of a proud Prussian officer to a mere Nordic boy. God knows, valiant Norway had earned the moment; and I hope that’s more or less the true story.

Whatever, on that first long day on the road, we bought fresh bread and small ripe tomatoes in a village shop; then stopped by a lake farther on in the countryside and opened our first can of corned beef. Even now, framed in my room among my fiercely selective gallery of Heroes and Worthies, I have the picture I took of Michael that day, handing me a plate composed of those elements. If I’d felt rewarded more richly by life than on that bright evening, more so even than at Heaven’s Gate six weeks before, I don’t recall it—the beautiful place unoccupied by others (so far as we could see) and the simple offer from a tested friend, as good to see as the far-northern lake and the trees beyond it, of all I needed to nourish me through the remainder of daylight.

Michael Jordan by a lake in rural Norway, July 1956. We’re consuming, at lunch each day, a can of corned beef from the case Mike’s mother bought us in England, plus the fresh bread and ripe tomatoes we buy on the road in some village by the smooth dirt roads which cross that admirable country, only just then repairing its Viking heart from the long night of Nazi oppression. Of the many dozen photos of Mike I’ve taken in a friendship that’s lasted more than fifty years, none speaks more eloquently of my friend’s undemonstrative generosity and the silent help he’s rendered many times when I’ve encountered problems ranging in seriousness from wretched food poisoning in the Merton dining hall to the paraplegia that felled me irreparably thirty years later. No other man I know of has had so loyal a friend through so many years.

I’d completed no fiction since leaving the States, though “The Anniversary” was well advanced; and I’d laid my thesis aside to be where I was. Yet I was sure I wasn’t deceiving myself when I felt I was doing the right thing for me—and doing it on Cecil Rhodes’s money, that steely empire builder who was almost surely queer (I regret that these occasional revelations may strike a reader like rabbits from hats, but I offer none that don’t seem relevant in their present context). What I was doing was laying down, by the hour, ardent life beneath me, achieved experience that would serve my future life and my work so long as I had a mind to use and time to use it in. And it was all happening with one even-tempered laconic, and loyal man. All these years later, however long I delayed the completion of my B.Litt. thesis, I can confirm the rightness of the choices a young fool made in the midst of his early twenties (the fool was me of course).

By dusk that day—past nine o’clock, far north as we were—we’d reached a small ski resort called Geilo. Half-dark was enfolding us on all sides; we were tired and it seemed unwise to push deeper into evergreen woods as dense as any forest in a Brothers Grimm tale. A small hotel loomed beside the road. Its surprised manager—surprised to have guests in early summer—took us in for a reasonable fee and, next morning, served us our first near-endless Scandinavian breakfast: mountains of impeccable open-faced sandwiches grandly displayed on a rising series of pewter racks, and for no guests but us apparently (no one else was in sight but a single waitress with a rosy complexion as flawless as any porcelain doll’s). Then off to Oslo on further dirt roads through denser forests past more boys shouting my license number at us.

* * *

On the outskirts of Oslo, Michael proved the existence of an innate skill I’d not known in anyone before—he possessed, as perhaps a genetic endowment, an apparently infallible internal compass (my mother had a good “sense of direction,” but Michael’s was amazing). In most cases that summer, our hoped-for first stop in a new city would be the railway station; and Michael could guide us straight there with no hesitation at any crossroads. We’d read somewhere that continental stations all had information windows which could give us the names of individuals, mostly widows or spinsters, with inexpensive rooms to rent in their homes. And lo! we found our Norwegian widow in no time, right at the city center: a clean room in an almost uncannily quiet apartment for the equivalent of eighty-four cents per night (I still have the receipt).

After a quick wash-up we walked out in search of dinner. Strange as it feels after five decades—and with no help from diaries—I can see the cafeteria we found and the entrée I bought—a hearty beef stew with potatoes and beans. Carbonade, it was called. The other eaters around us were likewise male—generally middle-aged and not quite destitute maybe but solitary and still wearing their overcoats, though the evening was warm. Maybe we’d stumbled on food largely patronized by the homeless; I’ve somehow always thought our fellow diners were veterans of the recent war, likely the underground (especially active in Norway).

In the next few days we ticked off the obvious local sights. First, the unique Gustav Vigeland park with the native-son sculptor’s swarm of figures—men, women, and children in every decent posture. Then the National Gallery with its numerous paintings by Edvard Munch—Norway’s great painter had died only twelve years before, and the dedicated Munch Museum had not yet opened. What was most imposing to one who knew his work only superficially—I’d studied it at Harvard two summers before—was the revelation of what a wide and deep range of response he’d displayed to so much human life, far beyond the riveting Scream. From the array of pictures in the National Gallery, it seemed he responded chiefly to female life, from his famous near-vampiric nude women to sick and even threatened girls.

The National Gallery also included a host of considerably less striking landscapes by other Norwegians, mostly in the shrill pastels that led Michael to take all he could before saying—some thirty seconds before I’d have said the same thing—“Enough, I think.” What was perhaps most striking about the best work in the city—Vigeland’s sculptures and Munch’s pictures—was the degree to which they had an immediately obvious personal flavor, a thoroughgoing originality that had somehow fought off the influence of other European art yet was nonetheless not provincial in the usually denigrating sense.

To clear our heads we found the local beach at Huk, near the center of town; and shoulder to shoulder with crowds of the locals, we surrendered our pale hides to a warm sun. And while I’d suffered the dark Oxford autumn days, now I could note in a letter home that “It’s still vaguely light at midnight and dawn begins at about 1:30.” I never stopped wondering how the birds stood it; when could they sleep? From three or four more days in Oslo, I’ve retained a memory of welcome warmth from the townsfolk we encountered, mainly in the outdoor café in the central square; yet just under the warmth was a rough-textured nature that seemed ready to fight for whatever it needed to remain itself.

It was surely no accident that all these people had once been the Vikings; and when we’d noticed the young Italian and Spanish men who’d already been drawn, in a lemming rush northward, to seek their polar opposites—the tall blond girls with fetching smiles who awaited them like vaguely superior doe-deer at the edge of a clearing, threatening to speak before they bolted—I trusted in their survival, though I’ve never had a chance to return and see.

In 1956, though, I could chuckle at the all-but-panting dark-haired boys who always seemed to arrive in packs, descending in their droves from tiny Fiats like circus clowns (thirty clowns from a minuscule car).

I’d begun to notice how both Michael and I were refusing to see ourselves as any brand of tourist. With tilted noses we claimed superiority to that. But how, in my own estimation? Well, I saw myself as a silent benign witness, hoping eventually to convey in useful words what I’d seen. I hope I had the honesty also to grant that a man who managed his combined hope to write and teach as badly as I was so far doing was a creature as open to loud derision as any priapic visitor from the south, but it’s taken me more than five decades to do so. Nonetheless, fifty years later I’m recording some memories of those days; and I’m nurturing the ongoing hope that—like the Italians who’ve survived so many millennia of invasions with ample grace—the Norwegians haven’t lost the trait I treasure most from my visit: their gradual readiness to smile with a slowness that made a grin, once it dawned on their strong-boned faces, seem a genuine victory you could add to your file of on-the-road achievements.

* * *

A few miles after we crossed the border into Sweden, we paused to spend a night near Säffle (near the great Lake Vänern) in the home of an elderly woman to whom we’d been recommended by a Brighton friend. The lady was plainly wealthy and gave us a guest room in her handsome country house. Our room alone seemed nearly the size and height of a high-school gym, and our kind hostess fed us well. Most memorably, she sat with us on her front porch in the after-dinner dusk and described—in carefully formed English sentences—her enduring shame, as a Swede, to have sat in that same spot at the start of the Second War and watched German tanks, trucks, and thousands of soldiers pour past her into hapless Norway (it was apparently a condition of Swedish neutrality in the war that Sweden would accept this hateful passage into an even smaller country, its eternal neighbor). Over breakfast next morning before we departed, she asked us please to remember what she’d told us last night. She didn’t say why and I didn’t ask; but her ramrod spinal dignity is clear in my memory, along with her story of what she well knew was an appalling human betrayal.

Through the station window in Stockholm, we found a private room in a fairly high-class youth hostel on the outskirts of town (the clerk pointed down the street toward the birthplace of Greta Garbo). On our first whole day in the city, we entered a downtown department store. Walking past its windows the night before, Michael had seen a necktie he liked; and we went in while he inquired about it. Since we spoke no Swedish, someone immediately fetched the store’s translator.

She was a woman a little younger than we—Birgitta Leander—and as the tie was wrapped, she talked excitedly of her plans to visit England and the States. Then by coincidence, as we explored the artist Carl Milles’s sculpture garden later in the day, we encountered Birgitta and her parents. They promptly invited us to dine at their home that night and soon dispelled any rumors we’d heard of Swedish coolness.

Next day we continued to learn our way through the handsome city—its old quarter and the noble spaces of the city center with the royal palace, the opera, and the broad canals. No other modern Western European capital has seemed so grand to me—grand without ostentation (I’ve never seen Paris, odd as that may be). We must have stayed there nearly a week; and apart from a museum or two and a Birgitta-led Sunday in the nearby university town of Uppsala where we drank mead in a tavern near some tall Viking mounds, my best memory of the time is an evening when we arranged to meet Birgitta at Berns’s nightclub. She’d be coming with her pretty friend Eva, whom we’d met at her parents’ dinner party. At the club, Eartha Kitt—then at the height of her fame—was to be the performer. And the plan was that Michael and I should go early to insure a ringside table, and the girls would join us at the end of the workday. As promised, they arrived well before the floor show and found Michael and me at an ideal table.

The girls were laughing as they spread a newspaper before us and said “Who is this?” I’ve neglected here to chart the growth of our beards; but there undeniably we were—our heads, large, on a page of that day’s Aftonbladet, the afternoon paper, under a Swedish caption that said something like “Summer beards are blooming again.” Our beards had indeed progressed remarkably since leaving England (had the near-constant northern light been fertilizing?). Mine was near-black and Karl Marxist in its profusion. Michael’s was a tawny blond and more spiffily shaped. How the picture was taken we never learned; but for us four—pleased with ourselves to be in a nightclub, sipping wine in the midst of worldly adults—it proved a cheerful curtain opener for Eartha Kitt, a sassy South Carolina native who gave us way more than our money’s worth in the course of a long evening of stage hijinks and song (the waiter let us sit through two shows).

* * *

When we left Stockholm soon afterward, Birgitta rode with us as far south as Copenhagen to visit friends (I never saw Birgitta again, but I know that she later came to New York and held an important position in the United Nations translation department). My memories of the then-smallish and quiet Danish capital include driving out to visit Hamlet’s handsome castle Elsinore (Helsingör), then the celebrated flea circus in the teeming midtown amusement park called Tivoli. Who but the Danes could keep an amusement park tasteful, and am I hallucinating when I recall that the flea circus featured a jumping-insect version of the chariot race from Ben Hur? Mainly, though, I recall long walks through an old city without the grandeur achieved by Stockholm but also, surely, with no such grand ambitions.

Mainly I recall our sitting in an outdoor café one late bright evening, surrounded by well-dressed Danish ladies who were smoking cigars as the news-in-lights crawled round a nearby building to inform us that Premier Nasser of Egypt had just seized the Suez Canal from its international keepers, the French and the British. Ah, there was a real world after all. Would it lean on us now (surely the West could hardly allow the canal to be closed)?

My car lacked a radio, our ignorance of Scandinavian languages had shut us off from printed news in recent weeks, and Michael and I shared the general oblivion of the young to news that didn’t directly affect our bodies. So the bad news came as a mild surprise, but neither of us was alarmed. Michael was the only child of a British war widow and may thus have been exempt from any draft (the same was true, in those days, of the only sons of American war widows). And again, I was in Britain on an annually renewable permit from the U.S. Selective Service authorities. In those years the American draft system had been sympathetic to serious students—my grades at Duke had saved me from the Korean War. While I could theoretically be summoned home for military testing and induction, any implications of this latest news—even in the tinderbox of Middle Eastern politics—hardly seemed likely to require my presence in the American armed forces. So our trip continued on its untroubled way with a few more days in Denmark; but why did I say, in a letter home, “The Danes are friendly to a fault”?

And before I depart Scandinavia entirely, I should record that another soused but amused Norwegian told Michael and me this not entirely unfair joke one evening as we strolled past the Royal Palace in Oslo—he conveyed it as urgent news we’d need for the trip. Two Norwegians, two Danes, and two Swedes are shipwrecked on a desert island. A whole year passes before they’re rescued. In the twelve long months, the two Norwegians have had a fight; and one has killed the other. The two Danes have formed a cooperative and are doing very nicely, thank you. But the two Swedes have not been introduced yet. Well, apart from our better experience with a few of the Swedes, the joke held water.

* * *

From Copenhagen we crossed by late-night ferry into northern West Germany and plunged straight down toward Jane and Liz in Munich. I have dim memories of bypassing Hamburg and Nuremberg in the dark—on the remains of Hitler’s pioneering autobahns (Michael was a faster driver than I)—and reaching Munich in early daylight. Having no notion of the girls’ location (Michael’s internal compass was on hold), I told him to pull over at the curb where two policemen were standing. Their uniforms were almost alarmingly like German uniforms of the recent war; I assumed they’d be helpful, though. But when I rolled down my window and—in English—asked for directions from the more lupine of the two men, he turned away from me to his colleague. They shared a dry laugh. Then, together, they said a few N words—words that I, with no German, heard as entirely negative (like nein and nix); and they waved us onward, out of their sight, with no trace of help.

As we stumbled toward our friends, I continued to see the word Dönitz on numerous walls and hoardings. I was old enough to recall that Admiral Karl Dönitz was designated by Hitler, in the last days of the war, as his successor. What I didn’t know was that Dönitz had, ever since, been in the Allied prison at Spandau and would be released in two months. It seemed at least possible that the men who’d scrawled his name on walls were awaiting his freedom with vague hopes of a Nazi return to power, if they were not in the grip of some grimmer dream. I began to wonder just where we’d come to.

* * *

The week in Jane and Liz’s bright American-style apartment was a welcome change from our stays with the impeccable and inexpensive but mostly silent landladies of Scandinavia. Liz was preparing to return to the States to complete her college years in America, and she’d already finished her work with Radio Free Europe and was ready to join Michael and me in some local prowling. There was an indelibly memorable venture to Dachau, the site of Hitler’s first concentration camp, built in the year of my birth, 1933.

The town of Dachau was a virtual suburb of Munich, some twelve miles away, giving the lie at once to those citizens of the larger town who claimed they’d known nothing of the camp’s eventual murders. Dachau was not primarily a death camp but a holding-site for political prisoners and, not at all incidentally, the 110 homosexuals who were counted on the day of the last roll call in April ’45. Nonetheless some 32,000 prisoners died there, some of them as the result of the typhus epidemics which swept through many of the Nazi camps. Since the liberation of Dachau had occurred only some eleven years before our visit, there had been very little decorating of the premises. The present national-park atmosphere most definitely did not prevail; and I still have the photos I took, showing the raw realities of the site on the day of my visit with Liz.

My and Liz’s visit? Unexpectedly, on our arrival at the gate, Michael declined to enter with us. I tried, in one sentence, to persuade him; he shook his head in a silent No. And I knew to go no further, but that was all I knew. I left it at that, and in all the succeeding years have never asked why he refused. He waited outside in the unblocked sun as Liz and I wandered for a slow hour through the near-deserted spaces. What we saw were wide and unadorned barbedwire enclosures, long frame barracks, and long low redbrick buildings that had housed the incinerator ovens that consumed many corpses—outside, by the covered trenches that housed many more, the plaques said with stunning economy (in German)—The Grave of Nameless Thousands.

A few old women lingered, apparently even more baffled than we, near the crematory. A few old men wore their Jewish prayer shawls and murmured prayers; a very few guards watched us but no one else. Years later I wrote a long story called “Waiting at Dachau” that arose from the experience. More immediately, in a letter home soon after the visit, I described Dachau as “one of the two most impressive things I’ve seen”—the other was the Sistine Chapel, and the claim still holds.

* * *

A night or two later, the four of us drove a swift eighty miles east to Salzburg for as near an antidote as one could imagine to so much horror—a festival performance of Mozart’s Le Nozze de Figaro. Conducted by Karl Böhm and sung by (among others) Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Irmgard Seefried, Christa Ludwig, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, it was a long but sublime evening. The fact that both Mozart and Hitler were Austrian, and that the conductor and more than one of the brilliant cast of singers had likely been members of the Nazi party, only complicated the richness of the evening.

Given my youth, I’d heard a rewarding number of great performances at the Met and on the surprisingly distinguished concert stage in Raleigh—where I heard Flagstad twice, Melchior twice, Marian Anderson twice, Pinza and Steber once—but as we drove back on another splendid highway, I silently reckoned I’d never hear a more nearly perfect ensemble effort in the service of a greater stretch of music. On that return to Munich, we spent most of our remaining energy laughing at something we’d heard at a polite Salzburg bar to which we’d retired after the music. Two older classic-American female tourists, straight out of a New Yorker cartoon, were discussing what we’d just heard. The larger of the two said to her friend, “I’m not really sure we got our money’s worth.” When her friend looked quizzical, the unsure lady continued, “Listen, when I hear great music, something in me just swells up; and tonight it didn’t swell.”

Three other events linger on from the week in Munich. Liz took Michael and me, for a drink, to the large beer hall—the Bürgerbräukeller—which was locally famed as an early meeting place for Hitler and his cronies and the scene of their failed putsch of 1924. It was clean-scrubbed and as charmless as a vast tile toilet, but did I expect charm from a Fascist cradle? Another day, Liz, Michael, and I returned to Salzburg for a morning’s walk through the old town, climaxing in a visit to Mozart’s birthplace—another hard-scrubbed site but one whose walls at least surrounded the authentic space in which one of humanity’s supreme benefactors began his life. Then we downed a big lunch, ending in my second chance at Salzburger nockerl, one of my lifetime-favorite desserts.

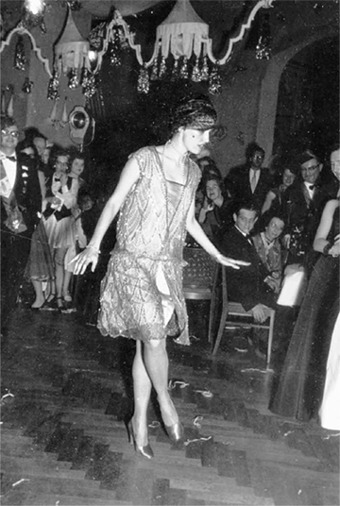

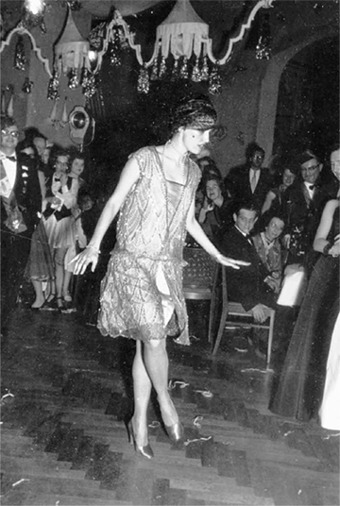

Jane Savage, dancing the Charleston in a dress of her mother’s from the 1920s. Jane sent me the picture in the 1950s, and almost ever since it’s been framed at my bedside. It was taken by a friend of hers at Radio Free Europe in Munich where she was working when Mike and I visited her and Liz McNelly in the summer of ’56. Jane had meant a good deal to me since we met in high school in the late ’40s, and there were times when I thought marriage might be a possibility (she may never have shared my thought). In any case, we brought each other a lot of pleasure and laughter till she married, moved out of easy reach, then succumbed to the slow ravages of multiple sclerosis, and died in her mid-sixties. In this costumed picture, she suggests—without obvious effort—both her gift for self-parody and her genuine grace.

Finally, the night before Michael and I were to leave Munich, the third memorable event came down. We went with Jane and Liz to a loud and eventually drunken party given by their colleagues at Radio Free Europe. By midnight, my childhood fear of drunks—their noise and the unpredictability of their hate—had sent me onto the porch to wait out the remainder of the evening. A patient soul always, Jane came out and joined me in an effort to turn my dislike of her friends. What always seemed my prudery at such occasions embarrassed me, and I surely had no problem with the fact that these oddly homeless Americans and exiled Easterners were sub rosa employees of the CIA—I’ve always thought that Radio Free Europe was one of the agency’s better ideas—so I unburdened myself of a good deal of the emotional history of my Oxford months.

I’d suspected all week that Jane had realized how much Michael’s friendship meant to me, and she’d shown no sense whatever of rivalry. I know I came near to broaching the matter, but ultimately my sobriety curbed me. So with her usual will to be defenseless, Jane moved into one of our first silences to tell me of the recently ended affair she’d had with an Eastern European at RFE—a man I’d liked in recent days. I was partly glad to hear of it—she and I, like most of our friends, had been so absurdly celibate all our lives—but I also felt a sudden steep wave of recalling how much she’d meant to me in the past ten years since I’d met her in our Raleigh neighborhood. I came very near a second proposal of some sort—marriage, whatever, I didn’t quite know. She was seated on the redbrick step just below me. I leaned way down, set my chin on the crown of her head—her blond hair—and dug right in. My hands didn’t reach out to turn her toward me; she didn’t turn but her head did press back hard into my sharp chin. I’m sure I thanked her—the few plain words.

* * *

Michael and I proceeded along the sunny Rhine for a good part of our way northwest. I recall bypassing Stuttgart, Frankfurt, and Bonn; then stopping for a night in Cologne. After the lack of obvious war scars in Munich and Salzburg (the Marshall Plan had done brilliant work in the hands of the notoriously able-handed and ambitious West Germans), it came as a surprise to see the condition of Cologne. More than ninety percent of the city’s buildings had been destroyed by Allied bombs in a total of 262 air raids; and at the end of the war, when West Germany was divided into zones of jurisdiction, Cologne lay in the British zone.

The British had, understandably, slim enthusiasm for encouraging the rebuilding of a country that had plunged them into war twice in twenty-five years. So the city we reached in late afternoon—the central city in any case—was a warren of only partly reconstructed single-or double-storied buildings, towered over by the giant cathedral that had also been damaged and was black with smoke but still strode triumphant above a huddled skyline. We stayed in a cigar-box-size room with a bombed-out widow for only one night, took a walk round central Cologne in the morning; walked slowly through the cathedral whose survival may well have been miraculous, and then were off.

Late the next afternoon—of a gray day—we crossed into Holland; and once we’d braved a literally incredible swarm of end-of-work bicycle traffic (hardly a car in sight but thousands of bikes), we found another widow’s room—a hilarious old woman—in downtown Amsterdam and ate a fine supper in an Indonesian restaurant (the Dutch equivalent of British Indian restaurants—colonial survival). Then we strolled through narrow streets in the dedicated red-light district. Informed though we’d been—like so many million tourists—we were quickly shown the reality of numerous attractive young women seated in windows a few yards from the sidewalk, polishing their nails, straightening seams in their fishnet stockings, meeting our eyes with the blank penetration of alluring cats but never once smiling (was a smile illegal?). One especially young girl did turn politely aside from my smile and dissolve in laughter; I stopped in my tracks, but she never looked back—not at me. I was tempted more than once to enter the open doors by the windows, if only to prove that the women were live and could actually talk. But neither Michael nor I took the bait, maybe because by then we were very near broke.

Like several other small but site-rich countries (Israel for instance), one of the numerous likable realities of a visit to Holland is that you really need to rent only one room. Then on public transportation you can easily venture all round the country—in Holland, nothing is much more than an hour from Amsterdam. So we stayed on in Amsterdam for several nights and submerged in a piece of amazing luck. The summer of 1956 was the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s birth. I take it as beyond debate that Rembrandt is as great a painter and draftsman as ever lived and that, further, he was at least as specifically Dutch in his vision as Praxiteles was Greek.

And Michael and I were now in precisely the right place on the planet to absorb two enormous celebratory exhibitions of Rembrandt’s work. In Amsterdam we saw as many of his drawings and etchings as could be gathered back to Holland for display at the Rijksmuseum. And in Rotterdam a comparably exhilarating wilderness of paintings was gathered. A two-day gallery visit was called for in either city; and we gave them that (only the gathering of Michelangelo’s work in Rome had provided a similar chance to see so much genius in so little space—and all of it near the scene of its creation).

What was almost equally astonishing was the fact that the Van Gogh family’s enormous collection of Van Gogh paintings and drawings was on display in Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum (there was not yet a dedicated Van Gogh museum). And almost as an afterthought, in another wing of the Stedelijk stood (temporarily) the original of Picasso’s huge Guernica in the midst of a lavish display of related sketches and plans. As one who’d already begun to immerse himself in the depths of seventeenth-century Europe, I’ll confess that Rembrandt and Vermeer reached me in ways that Van Gogh and Picasso didn’t, not in my early twenties. Of course I admired the more recent painters; but I wasn’t yet deeply moved by them. Still I bought a full-size reproduction of Van Gogh’s very late Crows in a Cornfield and would soon hang it in my room in Headington.

The pleasure that spread in rings round the silent landing in my mind of a genius as comprehensive as that of Rembrandt or Vermeer has never ceased nor diminished within me. But time would ripen me for a greater vulnerability to the often hectic, sometimes serene, art of the more nearly contemporary men. Even now, the older painters still move me most—largely through their power to console. I take it that any sane human life, as it moves on past—say—the age of fifty is grateful for literal help in learning that its pains, griefs, delights, and hopes are shared; and the older painters offer such experience, steady and clear.

* * *

There were further Dutch sidelights of the Rembrandt summer. Despite our happiness with the jokey widow in Amsterdam, we soon discovered a reason to move to the Hague. Because of the crowded gallery conditions in the two large cities, all the Vermeer paintings that still belonged to Holland had been gathered in the Hague in—can my memory be right?—a single middle-size room of the Mauritshuis: among them, the Girl with a Pearl Earring, the View of Delft, The Little Street, The Milkmaid, and the Woman in Blue Reading a Letter.

For three nights then we found a room in the home of a large and thoroughly warmhearted family—the Sanderses. In our evenings we dined with them and then played quietly ferocious games of Monopoly with the parents and children. Otherwise we walked through the small leafy city and spent as much time as possible with the Vermeers. Among those immaculate and immensely complex pictures—each of them apparently breathed effortlessly onto their canvas or panels—the Woman in Blue Reading a Letter would work steadily in my mind after the visit and play a crucial role in suggesting to me the subject of my first novel. The picture shows what appears to be a pregnant young woman dressed in blue, standing before a large map (of what distant place?) and facing a well-lit window as she reads a letter (from whom?). In the Mauritshuis I’d stand and study the picture as I’ve never, before or since, felt compelled to study any image—setting my eyes to prowl the relatively small surface with the relentless thoroughness of a spy-in-the-sky satellite.

In our final days in Holland, we visited Delft for the small-town sense of Vermeer’s life (he was born and lived there always). His father’s narrow house still stands on the spacious central square, crowded though it is with Delft-blue porcelain shops which may nonetheless provide a clatter similar to the one through which Vermeer persisted, daily, in his creation of the phenomenal silence of his pictures. And as a fitting end to the trip, we took a long walk on the vacant and windy beach at Scheveningen where Van Gogh had often worked. Then five weeks after our departure from Newcastle, we returned on choppy water from the Hook of Holland to Harwich on the southeast coast of England.

Fine as the days and the long miles had been, I was ready for a stretch of solitude; no doubt Michael was also. We each had almost two months of the Long Vac left. I’d be faced again with the question of where to stay; we’d both need to get down to concentrated study. Meanwhile it’s worth noting that we’d completed that rarest of travel ventures—a long car trip, with all the enforced closeness such a trip entails, yet one without a single falling-out. If either Michael or I felt the need of a free breath, we wandered off for an hour of reading beneath a tree; or we sped up, two rooms ahead in a museum and indulged in private viewing.

One of the travel skills I learned from Michael was the wisdom of declining to discuss paintings, cathedrals, or even mountainscapes while we were in the act of viewing them. Discussion, if called for, could occur over our next meal; any disagreements would have cooled by then. Michael’s natural quietude had no doubt engendered the skill in him years earlier—later I’d learn that he likely acquired the trait from his mother, a woman who’d spent much time alone since her husband’s death, if not before—but through a trip as long as ours, his taciturnity damped down my Southern tendency toward instantaneous babble and thus any number of on-the-road wrangles.