13

IN THE FACE OF those realities, I’d recalled my and Michael’s sightings of Stephen Spender the previous Easter in Venice. In addition to the writing of his poetry and a large body of essays and reviews, Spender also co-edited the magazine Encounter which had rapidly become one of the liveliest literary and political monthlies of the time. In the fall then I sent him three of my short stories and brashly suggested my willingness to come to London and discuss them with him. He replied to say that he’d be out of town for a good while but would contact me on his return. And he did. So in mid-December, just before the three-hour drive to Brighton, I went to London and met with Spender. Till then I’d read a number of his early poems and, above all, his autobiography World Within World, as much admired today as it was fifty years ago.

I was clearly contacting him in the hopes of placing a story in his magazine. Almost as much I was hoping for more professional comment on the work, which is why I included a copy of “A Chain of Love.” Though I’d learned in his memoir of an early history of intense male relations, I’d also read that he was married for a second time and had two young children. He’d implied in World Within World that marriage had shut down his intimate male relations; and I was naïve enough in the understanding of erotic realities to believe the implication (most of the world, then, was as uninformed as I). I certainly had no intention of reigniting banked coals; my own emotions were firmly committed.

I called on Spender in his office then, in Panton Street just off the Haymarket, two blocks from Piccadilly; and we went out at once for a good lunch at an amusing all-vegetarian restaurant nearby—he was not a vegetarian. We laughed a good deal when he ordered (and commended to me) an item called nut cutlets which proved to be delicious. I can’t recall the name of the restaurant, only that the conductor Antal Dorati was seated nearby (as though nut cutlets exerted widespread magnetism on distinguished artists) and that Spender’s response to my stories was encouraging. Like David Cecil, he’d turned a working writer’s eye on my pages; and he asked if “A Chain of Love” was available for publication. I told him of the interest of The Paris Review; but faced with an apparent interest on his part—and given the distinction of Encounter (and the chance of its paying a good deal more), I may have said that its fate was not sure. I’m fairly convinced that I didn’t reveal the fact that Diarmuid had said the story was accepted at The Paris Review.

At this point, so many years later—and in the absence of a diary or other records—I’m entering here on an honest uncertainty. I’ve mentioned The Paris Review’s youth (it was three years old) and my awareness, at least, that little magazines died with the speed of fruit flies. Encounter was virtually the same age; but it had already won international notice for its superb offerings in poetry, fiction, and political commentary; and it seemed to be firmly financed (it would be years before I knew that it, like Radio Free Europe, was largely funded by the CIA). Furthermore it was an English magazine; and I was living in England, surrounded by English friends. Its famous co-editor was my host at lunch, I’d sent him my manuscripts months earlier, and he seemed to be showing genuine interest in publishing my till-then best work.

So I think, again, that I told Spender “A Chain of Love” might be available—I’d need to check with my agent. I was vaguely aware of differences between U.S. and English rights in some literary publications. Mainly though I was flying blind, and I made a bad mistake in waffling on the matter of the story’s freedom. Whatever, Spender did say that it would be difficult to sell such a long story to his colleagues on the magazine (his co-editor was Irving Kristol, and Dwight Macdonald was spending a year in London as a visiting editor). He’d have to let me know as soon as he could present the story to his colleagues. A little sheepishly, I nodded my powerfully conflicted hopes for his success. In the face of the very real poverty visited on me by a previous year of expensive gallivanting, a good deal of my silent conflict centered round the fact that Spender had mentioned what Encounter might pay for such a long story—the present equivalent of $865, an almost literal stack of gold to a man in my situation.

* * *

By then we were at the end of a winey lunch; and Spender suggested that—since I had my car, and his day at Encounter was done—I could drive him to his house, meet his children, and see his pictures (we’d talked a good deal of our interest in collecting art, an interest I’d lacked the funds to realize, except for a fragment of a marble Roman Venus which I’d bought for fifty dollars in Cambridge, Massachusetts some three years ago). We drove north then into the respectable, but hardly glamorous, district called St. John’s Wood and on to his pleasant nineteenth-century house on Loudoun Road. The children were still at school, as I recall; but Francesca, the live-in Italian maid, served us coffee in the comfortably furnished sitting room. Its chief feature was a concert grand piano, the prime possession of his wife Natasha Litvin who was still performing publicly and who’d be in America doing just that for several more weeks.

When the children soon arrived, we struck it off at once. A married friend of mine—the father of three—always says “Only bachelors have ever known how to rear children, and they forget as soon as they marry.” I’ve mostly had good luck with children—mainly because I’ve tended to treat them, benignly, as if they’re adults. Since their parents almost never think of them as grown-up, the youngsters can hardly avoid liking me. The Spenders’ son was Matthew; the daughter was Lizzie. In fact it became uncannily clear, in the course of the afternoon, that we were arranged in a remarkable set of chronological stairs—Stephen was forty-eight, I was twenty-four, Matthew was twelve, Lizzie was six, and Francesca’s son Dimitri (who was playing among us) was three. The numerological reality seemed a Jungian blessing on our day, and Matthew was especially impressed.

Matt—then also known as Matteo—had the grave seriousness of a lanky boy just on the edge of puberty, but he welcomed chances to laugh; and when he accompanied me on a tour of the numerous paintings, drawings, and etchings in the house, his comments were often keen (of a Henry Moore drawing of his father as a lean, almost hypnotically focused young man, Matt said “It makes me see how much I wish I’d known Dad then”). Lizzie was a lively charmer, much given to laughter and a normal young girl’s fantasy-love of horses (she didn’t yet have a horse). Like most children, what they eventually seemed to enjoy in my company was my tendency to tell them stories from my own childhood in quite a different world. I’d noticed, long before, that children find it impossible to imagine that their elders were ever really young. Any narrative proof of the fact is generally welcome to them and can prove magnetic, if the narrating adult is even mildly amusing.

When at last I said I must head back to Oxford, Stephen and the children asked me to stay for dinner and I did. The four of us lingered in the downstairs dining room; and Francesca served us a grand meal—roasted lamb chops, risotto, salad, and a silken crème caramel. The chance for Italian home-cooking was again irresistible (though after college food, dog chow might have proved welcome); and the air round the table was relaxed and frequently hilarious. When the time came for the children to retire, they seconded Stephen’s invitation for me to stay the night—the drive back to Oxford would take an hour and a half. I’d brought nothing by way of sleeping equipment, so I promised them—Francesca included—that I’d come back soon for a night. Their enthusiasm for a weekend’s visit seemed, and ultimately proved, to be genuine; and my exile’s yearning for family was again aroused.

* * *

Back in Oxford in mid-January, I was in my sitting room on Sandfield Road, reading a month-old copy of The Warren Record, the county weekly from my most-native-of-all-heaths (my aunt Martha Reynolds Price had sent me a subscription). As many small newspapers then did in December, the paper published a column of children’s letters to Santa Claus with the usual requests for Christmas presents—toy guns, baseball mitts, dolls, tea sets. As I proceeded through the familiar details, I suddenly saw how to end a story I’d been thinking of for more than a week. It would be a story about an illegitimately pregnant girl; and my sudden apprehension was that the story would be about a young woman whom I’d portrayed, in her adolescence, in “A Chain of Love.”

Her name, again, was Rosacoke Mustian; and she, like me and my parents, was from Warren County. Her reluctant boyfriend was named Wesley Beavers; and somehow I’d narrate the details that brought Rosa to her realization of the unwanted pregnancy and her eventual decision, I knew at once, would resolve itself in Rosacoke’s mind as she played the familiar role of the Virgin Mary in the kind of small-church pageant in which I’d participated more than once in my childhood. When I recorded my finding in the notes I kept for possible fiction, I added this—

If I finish the story and it’s fine, then when I have a whole book, I can put “A Chain of Love” as the first story and this one as the last.

Quickly the entries in my notebook began to multiply, all concerned with the new story. And a week later the entries are dated from London. As promised I’d returned to the Spenders’ house to spend a few days with the family. Stephen, his children, Dimitri, and I spent a Sunday with a good long walk on the rolling terrain of Hampstead Heath (with another glimpse of the Vermeer at Kenmore), and a drive past the house where Stephen had spent his boyhood. Then he and I passed a bibulous and cheerful long evening with his friend the distinguished essayist Cyril Connolly. I would see Cyril a number of times in the next few years, but that first meeting is especially vivid for me still.

* * *

He and Stephen had worked together in the early days of their celebrated and historically important magazine Horizon; and their work now was separate—Stephen at Encounter and Cyril as a regular book columnist for The Sunday Times—but their mutual affection was apparent, despite the fact that Cyril’s slight seniority (and his murderous wit) still laced his remarks with ironies and insults which Stephen appeared to enjoy without reservation—at least he laughed heartily and never riposted in kind. Cyril took the classic British Older School Boy role in their friendship, Stephen played the Hapless New Boy; and they each clearly relished a conscious assumption of their roles, especially in the presence of a new consumer like me who’d never heard their best tales.

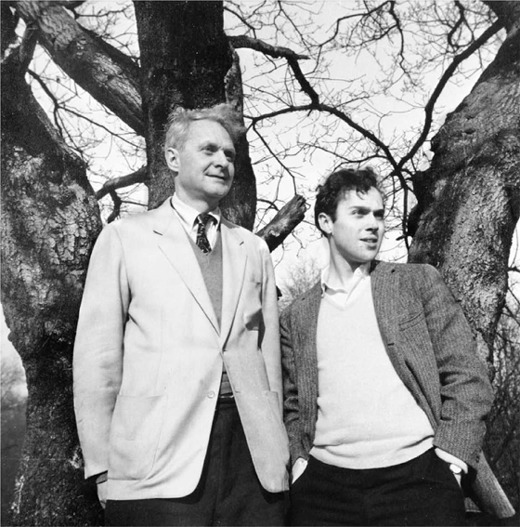

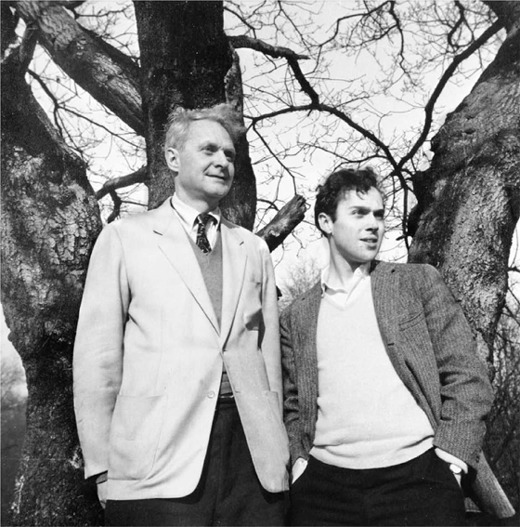

Stephen Spender and RP on Hampstead Heath, January 1957. Matthew Spender, who was then twelve, took the picture in the midst of a long walk on the Heath one bright Sunday morning (Lizzie Spender, age six, was also with us, as was Dimitri, age three, the fine Italian cook’s son). It was my first visit to the Spender household and a happy one—as they’d all prove to be. Here Stephen looks half a head taller than I but he wasn’t. Maybe he was standing on a small hillock or a root of the tree behind us—he was six foot, two; I was five, ten and a half. Some of the excitement I read on my face in the picture results from the goodness of the visit; the remainder comes from the fact that I’d only just conceived the story that would—some five years later—become my first novel, A Long and Happy Life.

At our first lunch together, Stephen told the story Leonard Woolf had told him about his first outing with young Virginia Stephen, the daughter of Sir Leslie Stephen. They took a train trip to somewhere in the country, the day went well; but on the way home, in their private compartment aboard the train, Virginia was struck by a dreadful need to pee. It was one of the old carriages with no corridor, thus no hope of a loo. Of course Virginia didn’t speak of her pain till she reached the point of cutting loose in her floor-length skirts. Only then could she burst out—“I’m dying, Leonard.” When he understood the cause, he took his copy of that day’s Times and made a huge circular funnel with no open end. Appalled but overwhelmed, Virginia turned her face to the landscape, squatted above Leonard’s improvised loo, lifted her skirts, drained her bladder, and threw the loaded funnel out the window. “There was no way not to get married after that,” Leonard had said.

In fact even in private I never heard Stephen say worse about Cyril than the incontestable fact that you had to be careful with your prize books when Cyril came to dinner or one of the most valuable might be inclined to follow him home.

In all our meetings I was lucky never to come in for one of the Connolly barbs, though when I told David Cecil of my first meeting with Cyril, David paused at length, put his long tongue firmly in one cheek, blinked rapidly as he did before launching a sudden discovery, and then said “Cyril is not as nice as he looks”—a thoroughly complicated Cecilian warning: Cyril was notoriously ugly, with a short plump body topped by a head that looked almost comically more like a Greek satyr (or the satyr-like Socrates, amazingly so) than anything remotely British.

And speaking of prized books, eventually Stephen would give me a first edition of the intensely personal and self-demeaning but wise document The Unquiet Grave. It was initially published in 1944 by Horizon under the name Palinurus, a pseudonym soon penetrated by all its literate readers. And many years later, I note that the inscription in the copy which Stephen gave me says, in Cyril’s large clear script—

For Reynolds Price

with affection

admiration

And in the

expectation of

benefits to come

from his friend

Palinurus

‘he is not dead, but sleepeth’

London 1961

An even more substantial work had long been awaited from, and by, Cyril (who semi-promised it for years); but it was never written. And long before he could have known of my interest in the Gospel of Mark, his “he is not dead but sleepeth” is a paraphrase of Jesus’ remark near the apparently dead body of Jairus’ daughter in Mark 5:39 (the King James version), “The damsel is not dead but sleepeth.” I’m glad to note that Cyril remains—with David Cecil and my father—one of the three most continuously intelligent, originally witty, and verbally elegant talkers I’ve known.

* * *

On that first weekend visit, I met another of Stephen’s friends, considerably younger than he but also funny and famously gifted—the painter John Craxton. John had come to public notice in his early twenties, along with his then friend Lucian Freud, through his haunting quasi-surreal drawings and paintings of British landscape. As soon as the Second War ended, and continental travel was possible, John made his first trip to Greece and seldom looked back. By the time Stephen took me to meet John, he was living on the top floor of his parents’ house in Hampstead, sporadically at work on several large oils of Greek shepherds and fishermen.

On that first visit, John also showed me dozens of small and inexplicably economical portrait sketches of Greeks whom he met briefly in cafés and wherever else, young men who (not yet entirely Westernized) could easily have stepped from Homer’s battle scenes, the somber tragedies of Aeschylus, or even the raucous ithyphallic comedies of Aristophanes—their adamant dignity and craving for life was still that firmly intact and vividly conveyed in a few pencil lines. My first turn through John’s sketchbooks was among my earliest experiences of the true collector’s longing—at once, I wanted almost all these drawings.

Meanwhile, since I’d ultimately spend a good deal of time there, I’ll note a few characteristics of the extraordinary Craxton household. John’s father was Harold Craxton, one of the most respected piano teachers of his time at the Royal Academy of Music. Between pupils, he wandered round the large three-story house with the distinctly vague air of a cartoon character—say, Mr. Magoo. Likewise in residence were John’s sister Janet, principal oboist in the BBC Symphony, and—somewhat later—their brother Anthony, a senior producer for BBC Television, frequently in charge of programs involving the royal family. John’s mother Essie—who often seemed harassed but was never less than quietly masterful—somehow managed to hold this unparalleled artistic menagerie together. Among them, almost from our first meeting, John became a valued friend.

Stephen himself became, in the few days of that first visit to his home, a friend who’d remain impeccably loyal for the rest of his life (and he died peacefully a year after I last saw him, when he was eighty-six). I’ve noted that I learned, from his autobiography when I was hardly out of my teens, how his past had been marked by a complex sexuality. Without burdening the reader unduly, I can honestly condense the nature of our early relation by recording that, from the day we met, I was aware that Stephen was signaling the possibility of a sexual intimacy.

The signals, though, came from the other side of the room (literally) in nervously laughing and thoroughly shy remarks. As hints, the signals were never pressing—they seemed offered almost idly as tests of a particular situation—and when I, first, ignored them and then made it politely clear that my feelings were otherwise involved, the cloud quickly dispersed with no ill will on either side. Despite the fact that Stephen was then twice my age—and knew so many men and women who were far more accomplished than the young man I was (Auden and Isaiah Berlin had been his closest contemporary friends since their undergraduate days)—we nonetheless had so much in common, in our lives and work, that an enduring friendship grew when one of its possible directions was shut off at the start.

By far the chief subjects of our earliest conversations were our reading, our love of music, of the great masters of twentieth-century painting, and our friends, eager to laugh at almost any moment—sympathetically, ironically, or mercilessly. In retrospect I’d note that my first responses to Stephen were virtually identical with my last. In 1994 I made my first return trip to England in many years—ten years after I’d taken to a wheelchair with the remains of spinal cancer—and saw Stephen back in the Loudoun Road dining room with Natasha (he was eighty-five; they’d been married for fifty-three years, and whatever waves had troubled the marriage seemed mainly calmed in mutual old age).

Stephen had a passion for the workings of the independent liberal mind, with all its most harmless foods and pleasures, like that of no one else I’ve known (the Spenders were an old liberal family). A department of that passion was his constant search for something that’s grown increasingly impossible to find—the kind of romantic friendship with which I’d also been increasingly involved since my own early days at Oxford—the physically imposing friend who’d share one’s deepest enthusiasms and engage with one in adventures that might range from physical love to dangerous gestures in the effort to aid another friend or even helpless strangers.

In World Within World, Stephen describes just such a gesture. When his former partner, whom he calls Jimmy Younger (the real name was Tony Hyndman), feels abandoned by Stephen’s impulsive first marriage, Jimmy flees to Spain to fight with the International Brigades in the Civil War and is promptly caught and threatened with execution. Stephen quickly follows him to Spain, and considerably endangers himself, in the attempt to rescue Jimmy (the rescue succeeded, Stephen’s marriage promptly failed, and the remainder of Jimmy’s life was a sad downslide).

The fact that Stephen’s poetry was always subject to almost violently opposing views from his readers—a paradox that virtually silenced his publication of poems in the 1950s and ’60s—was a humiliating sadness for him; and I can only be glad he wasn’t alive to read the recent British reviews of his posthumous Collected Poems. For an American who’s loved, studied, and written poetry with attentive passion for more than six decades, it was astonishing to see how almost completely those reviewers failed to recognize the kind of poem Stephen Spender was always trying to write and often did—a neo-Romantic lyric, all but anti-Modernist in its tones, rhythms, and actual vocabulary and profound in its feeling. It’s my conviction that, in time—when the enemies he accumulated so readily in the course of a long and politically stormy public life in Britain and America have likewise died (he published a number of intemperate and often hilariously sardonic reviews in both countries and thereby earned a portion of his treatment)—several dozen of his poems will be seen as strikingly original and piercingly true to a particular time, place, and extraordinary mind. Of how many continuously anthologized poets can we say more?

* * *

During the remainder of my first stay on Loudoun Road, there was a dinner with Malcolm Muggeridge, who was then editor of Punch and by no means the doctrinaire Christian he later became. Toward the end of a good deal of wine, I recall his saying to Stephen words to this effect—“Don’t you know how fond you can become of a man whose wife you’re fucking?” Stephen laughed nervously and nodded. There was a dinner with Cyril Connolly and Lionel Trilling, who was in England without his widely dreaded wife Diana (Stephen and his friends had heard with relief that she hated flying). Trilling himself was quietly polite, though he gave off a soberly academic whiff of disapproval of these laughing English writers; and they of course could never forget that he’d written an entire humorless book about E. M. Forster without perceiving that Forster was queer.

Still, I enjoyed a Sunday afternoon’s visit to the Royal Academy show with Trilling and Stephen and a Sunday-afternoon lunch at Loudoun Road with Trilling, Cyril, and Rose Macaulay, who was by then an ancient-seeming woman (only five years older than I am now but as shrunken as the Cumean sibyl); her recent masterpiece, The Towers of Trebizond, was a novel I’d much admired and have continued to read. Also at the table for Francesca’s ample spread was Sonia Orwell, the widow of George Orwell. I’d see Sonia many more times in my last eighteen months in England and always found her good-looking, warm, and funny—never the difficult and inscrutable person she apparently became in her last years. Toward the end of my visit, I began to wonder at the furious pace of Stephen’s social life and slowly came to realize—over many years—that he literally craved the mental stimulus of very bright friends: fine conversation, in a single word. I also learned that—infallibly—at the end of the busiest day, he’d go down to the cleared dining table and work till the early hours—on poems, his journal, or a short novel he’d just begun. It was ultimately published as Engaged in Writing and concerned itself with the grave, and comical, Cold War–cultural problems that arose in the Venice conference which he was attending when I first saw him.

So my first stay at the Spender household—some ten days—ended with our attendance at a performance of Beethoven’s Fidelio by the Sadler’s Wells Opera. Fidelio had been among Stephen’s highest pleasures since his early visits to Germany and Austria. This performance in January ’57 was sung in English by competent British performers. And while it had—almost unavoidably—stretches of musical and dramatic excitement, it was no match for my own prior Fidelio, a thrilling performance with Kirsten Flagstad which I saw and heard Bruno Walter conduct at the Met in March ’51. Nonetheless the evening provided a useful marker for the start of a friendship that would help us both powerfully through four more decades of life and work.

A final marker of that long week was the fact that, on my last morning in London, I went with Stephen to the Zwemmer Gallery to see a small show of the etchings Picasso had made, years earlier, as illustrations for an edition of the Metamorphoses of Ovid. Those uncomplicated line drawings of superb elegance were so cheap that Stephen bought several; and even I, broke as I was, bought one: the fall of Phaeton in the chariot of the sun for only twenty guineas (a guinea in the currency of the ’50s was a pound and a shilling, hence twenty-one shillings). I also got to meet Mr. Zwemmer himself, a white-haired and distinguished feature of the London gallery world whom I’d eventually see more than once again.