15

I SPENT THE LONG VAC almost steadily at work, initially in Oxford. Stephen had asked me to write an omnibus review of several novels for Encounter; and I readily undertook the task—reading Camus’s last novel The Fall and Iris Murdoch’s second and writing about them with the deplorable condescension so endemic to the reviewer’s trade. The fact that Camus might have read my review before his early death only some three years later has always troubled me—Encounter was widely discussed in intellectual France; and while no one there would have heard of me, any bad review is a bad review. And at Redmayne’s in Burford, I’d soon meet Iris Murdoch with her recent husband, my friend John Bayley from New College. If Murdoch had read my notice, she cheerfully forgave me as the twerp-in-training I’d soon decline to be again.

I knew that Stephen would leave in late August for a long lecture trip to Japan, and I made a few evening efforts to see him in London before his departure. Much the most impressive was a chance to see Peter Brook’s production of Titus Andronicus yet again when it was revived at the huge Stoll Theatre in London for a few weeks in July ’57. It was my third chance at this revelatory production of a play that had for so long been considered unproducible tripe. Before the performance Stephen sent a note backstage to Vivien Leigh, saying we’d like to come round at the final curtain and see her. Not ten minutes later a young man came to Stephen’s aisle seat and said that Lady Olivier would welcome us with pleasure.

Her performance as Titus’s daughter Lavinia, earlier at Stratford, had been derided by Kenneth Tynan—Leigh’s pursuing critical night-mare—as a travesty of the role’s demands for horror. In contrast to her husband’s sulphurously powerful Titus, with its great speech “I am the sea” and his quite credible amputation of a hand, Leigh’s portrayal of Titus’s daughter—raped, with her tongue and hands shorn away—was far more unreal. Her Lavinia was balletic in its stylized beauty and enforced silence in the face of Olivier’s bellowing realism. As Leigh saw it, Lavinia had more than half preceded her father already into some imposing but fearful afterlife; and from here, my memories of her appalling grace are stronger than my surviving pictures of him.

Backstage she greeted us in her dressing room with a Scarlett O’Hara brand of hospitality, telling Stephen that she’d merely told her assistant to go into the stalls, find the best-looking man, and it would be Stephen. We talked on with her awhile longer, and I found it hard to do more than focus on her face—to this day, the most beautiful woman in my well-populated experience. When I heard someone behind me, I looked round to see Alec Guinness and his wife. Guinness had been Olivier’s Fool in an earlier performance of Lear; but tonight he seemed present as a fellow actor’s duty and was otherwise polite but cool, almost cold-fish cool.

When it was time to leave, Stephen and I both kissed Leigh’s cheek; and Stephen asked her to give his compliments to Larry. She pointed to a nearby shut door and said “He’s just there. Do speak to him.” Stephen tapped on the door, one of the world’s famous baritone voices said “Come in,” the door opened; and there stood Laurence Olivier naked as a jay. He was obviously changing into street clothes and was talking with his old friend John Mills, one of my favorite film actors ever since his performance as the adult Pip in David Lean’s Great Expectations. As Olivier stepped into his underpants, we stood beside him, exchanging a few pleasantries about a play that hardly bore pleasantries. I’d never met him before, and he seemed exhausted and distracted in a way that his wife hadn’t. But then, I thought, he’d had the larger role; and we’d caught him in his unattractive starkers (as my Oxford friends might have said).

What I learned only years later, when various biographies appeared, was that the Oliviers had just returned from a tour of the Continent which had carried them as far east as Yugoslavia. Along the way Leigh had undergone one of her most intense and prolonged manic seizures. Manic depression had begun to trouble her at the time of her triumph in Gone With the Wind, and its ravages from the mid-1950s onward (though amazingly well concealed from the public and even her closest friends) had grown more disturbing as the years passed; and these were years before the development of effective treatments. Only a day or so before we spent our calm time with her, she’d very improperly risen in the gallery of the House of Commons and loudly protested plans to demolish St. James’s Theatre, a building that had been important in her and her husband’s careers. She’d been ushered politely from Parliament and told us candidly about a very kind message of chastisement she’d just received from Winston Churchill, an old friend.

Following our pleasant meeting with them—they were, after all, great actors, superb concealers—the Olivier-Leigh marriage had a few tormented years left; and her troubles slowly ebbed once he’d left her. In any case, she worked on to the end—especially in memorable productions of Jean Giraudoux’s Duel of Angels with Claire Bloom and with Gielgud in Chekhov’s Ivanov—and she died of recurrent tuberculosis while preparing to rehearse the female lead in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance. As great a force as Laurence Oliver exerted on the British and American stage, and in more than one influential film, I’m convinced—after many watchings through the decades—that Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett in Gone With the Wind and her Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire are comparable to one another in their dark power and the generous heart they display. And in her Anna Karenina she managed effortlessly to surpass Garbo’s famous performance; in fact Leigh’s Anna may be her greatest work, though in too short a film.

What’s clear above all is her utter willingness to burn herself as a kind of sacrificial fuel for her ambitious art right before the eyes of an audience, crowds of strangers down into the future wherever films are shown. But the husband who left her, superb as he was, also left a resonating narcissistic chill on much of what he touched (in fact, of all the stage and screen roles I saw him in, only his Titus, his Macbeth, and his Archie Rice approached Leigh’s greatest work).

* * *

In the spring months, I’d had a few more chances to see, and like, John Craxton and his teeming family household; so when The Paris Review contacted me urgently in late July—they sent a telegram—and asked if I could get an illustration for the story immediately and rush it to the printer in Nijmegen, Holland, I thought of John. The obvious implication was that the issue was on-press and a drawing was needed at once. Innocent of the strapped and understaffed ways of a youthful literary quarterly—run with some apparent confusion from both Paris and New York—I hurried to London and asked John if he could quickly provide a drawing. He agreed, read the story, and promptly produced a striking pen-and-ink drawing—Rosacoke in the final scene, delivering her flowers to the hospital room of an unknown family across the hall from her own sick grandfather. As instructed, I sent the drawing off, in considerable enthusiasm directly to Holland—and eagerly awaited my first professional publication: these young editors really meant business.

Wrong. In early August they sent me proofs of the story but added that publication had been delayed—no indication of when I should expect it. More than ever, I felt that Diarmuid and I had made the wrong choice (even if George Plimpton was also Diarmuid’s client). But when Stephen left for Japan some two weeks later, I don’t think I mentioned the delay in Paris. Only a few days later, though, I heard from the Paris office again.

They wrote to say that the Craxton drawing was inappropriate and could not be used. They enclosed it in the same envelope—no protective cardboard, the drawing folded, no apparent awareness of Craxton’s eminence in Britain, and no offer to pay him for his prompt work. I was foaming at the mouth in no time; but I kept my own counsel—no immediate contact with Diarmuid or John Craxton. Then in early September I wrote to Paris and, in the face of their astonishingly cavalier response to the fine Craxton drawing, I withdrew my story. Whether or not Encounter’s interest would survive, I couldn’t know, especially now that Stephen was in Japan—which in those days was virtually the moon—but I felt that, given the treatment my work and my efforts had received, I had no other choice. A wiser young writer might have discussed the matter with his agent or his original contact at the Review, William Styron; but what I saw as justified wrath drove me ahead. Plimpton and I corresponded later, and peacefully, about the dustup, and (in the patience of time) he arranged in 1991 for me to be interviewed for the Review in its famous Art of Fiction series.

* * *

Toward the end of August, I drove to Brighton and shared a farewell dinner with the Jordans and a few of their friends whom I’d grown to like. Then I drove Michael and his mother to Southampton for his departure to the States on one of the smaller Cunard liners. To be sure, I was sad to see him go. The first two years of our friendship had been as nearly flawless as friendships manage to be. And by the end of that second year, I’d visited in Anne Jordan’s flat so often that she told me—as we drove back from Southampton—to feel free to stay on with her as long as I liked now that Michael’s room was empty.

I’ve noted that the flat, with its airy balcony, was mostly vacant all day; and it became my working place for the remainder of the vac—on to early October. Through September I’d write away at the thesis from the time Anne left for work till midafternoon. By then I’d be near blind with discussing Milton and Greek tragedy; so I’d take a break in downtown Brighton, then return to Anne’s for a quiet supper and a couple of hours of television with her. On weekends we’d take short jaunts in the Beetle through green rural Sussex; and I’d enjoy visits from her friends and (especially for me) from her aged mother, Mrs. Almond.

Mrs. Almond was then in her late eighties; and though she was friendly with me in her native gentleness, her memory had failed badly. Anne would leave her office at midday and race, by bus, to her mother’s house to feed her; and getting her to eat was becoming a problem. She was seeing herself in a large mirror, thinking another woman was with her there in the room, and saving most of her own food for the woman in the mirror—demented no doubt yet employing the same kindness she’d imbued in her daughter. On her visits to Anne and me on weekends, whenever tea or supper was served, Mrs. Almond would always open her purse and try to pay as if we were out at a restaurant or tearoom.

The sweetness with which she seemed to recognize me at every meeting contrasted as boldly as possible with the equally old woman who lived directly across the street from Anne. That woman likewise lived alone with no apparent care and no visitors; and she’d frequently rush out into the street and shout her lurid fantasies—mostly sexual—to surrounding houses, shaking her fist in impotent fury at the windows behind which her watchers (me included) lurked. None of us ever went to help her.

What would help have been, barring a phone call to “the authorities”—who were they; and what could they do but haul her off from the place she knew and lock her away? The sight was my introduction to hopeless senile dementia, which I’d never before witnessed, as the sight of Mrs. Almond’s calmer confusion was likewise new to me and pathetic though closely cared for. But the writer in me watched both women closely. I even recorded, in my notes, a few of the wild woman’s shouted words out on Prince’s Crescent.

I’ve mentioned late-day pauses. Almost every afternoon I’d drive downhill, park on the seafront, and take long walks. In those days the town of Brighton, and its adjacent neighbor, Hove, came in several varieties. There was the seafront with its elaborate piers and their sideshows. There was a long spread of hotels, ranging from the thoroughly upper-class to the lower-middle or the decidedly sleazy. There were the handsome nineteenth-century residential crescents, the bolt-holes of well-off London businessmen and theatre folk. And of course there was the sea itself, though the English Channel at that point was more nearly a large gray lake lapping the shore like an elderly and halfhearted spaniel. The shore itself consisted of shingle—large rounded stones, no sand whatever—and seemed to me so uninviting that I never once sampled its offering.

Immediately inland there were the Lanes—virtual paths past dozens of shops that, again, ranged from excellent antiques purveyors to tourist junk shops peddling the usual seaside rubbish. But I loved their array of postcards and collected those with drawings of hugely busted women and spindly puzzled men engaged in comic action with ribald implications—ribald but not quite pornographic: We are British after all! In those days opportunities for food ranged from seaside stands with winkles, through good pub food at any number of saloons, to expensive restaurants for those with the money and the inclination. I roamed through many of them but seldom paused—again my cash was all but gone.

Apart from Michael’s mother and a few of her middle-aged female friends, I had not a single local acquaintance, despite the obvious availability of sexual merger with any number of female prostitutes—some of them beautiful, some classically whorish—and men of all ages, most of whom appeared to be offering their sometimes attractive services free. I can honestly report that I touched no one; and in retrospect I’m mildly sorry (I’ve never paid for sex in my life; what might I have learned if I had?). So my afternoon roaming through a quiet but crowded city served to deepen my solitude.

At first I missed Michael badly; and staying in his room—his actual bed, with his books and some of his clothes at hand—deepened my sense of the absence of someone who’d mattered more to me than anyone but the closest of my kin. Yet again I’d never been led, by him or myself, to expect another outcome of our two years together. I trusted that those years were bound to come to something else for us, wherever we lived thereafter: enviable tokens of loyalty that they were, of reliability in whatever straits, promises of occasional reunions with lashings of nostalgic laughter. Yet I worried about Michael’s welfare when there was no word in nearly a month. At last a letter, addressed to his mother, arrived while she was at work; and for the only time in my life, I steamed the air letter open, read his uneventful but safe news, and resealed it in a manner that might have won me a job in the better divisions of the CIA.

* * *

Solitary though I was then, I don’t recall that solitude as loneliness—even as, with shut eyes, I’d roam a strange and always abandoned-seeming spot called the Scented Garden for the Blind in a park near Anne’s flat. After my midafternoon walk I’d return to the flat to write another page of my thesis before I’d welcome her back and begin to help her with dinner. Not only had my hundreds of hours of childhood solitude prepared me for such life, I was also bolstered by my confidence that I now had at least one friend I could love as calmly as I then needed to love. The fact that the friend had been plainly, from the start, set for women was somehow a part of my attraction. And when I say somehow, I’m not withholding any degree of my own understanding. The fact that a few straight men have been, for a while, the responsive loves of my life is a large mystery for me, one that has sometimes produced real sadness but ultimately great reward—a reward that proceeds from a kind of love that I go on failing to understand.

In his remarkable preface to Shakespeare’s sonnets, Auden discusses what he calls the Vision of Eros. Auden asserts that in the real world there exists a rare and divinely inspired vision which can suddenly endow one person in the eyes of another with extraordinary radiance and thus produce a mysterious union that is otherwise unheard of, and he sees such an endowed vision in Shakespeare’s otherwise inexplicable love of the young man who’s addressed in at least 126 of the sonnets (though Auden later regretted his parallel assertion that Shakespeare’s love never found physical consummation). Such a claim of supernal magnetism is clearly not incredible; there’s a great deal of evidence for its validity in thousands of lives—if we think that Auden’s enduring love of Kallman proceeded from something other than foolishness, then it would seem quite possibly to proceed from some such vision.

I also feel that I underwent such a relation in those first two years in England. But why should anyone be inspired—by God or whatever power—to love someone who cannot spend his life with you? Shakespeare’s answer might well have been “The answer is here in these beautiful sonnets; these poems are the lasting product of that vision, surely an adequate reward for both partners.” My own answer—one that’s always satisfied me—is simply “Why not? Is any ultimately harmless love not better than no love?” And finally it’s been the fortunate truth to say that anyone I’ve ever really loved is still of profound value to me.

* * *

Toward the end of that second year in Britain, I couldn’t have claimed to foresee that reality; but I know I felt no desperation, no sense of abandonment by God or man and, again, no guilt in being launched on a love life which so many believe to be anything from absurdly wrongheaded to abominable. I partly regretted the silence enforced by society; but since my solitary childhood, I’d always been a thoroughly private person. What I didn’t relate, even to my kind parents, was the majority of what I thought and felt. My life felt like such an endless process of becoming that I could seldom pause and say This is where and who I am at the present moment. I was also a collector-in-training. I was saving the best of my inner life for some future offloading, some useful revelation that might detain and amuse my tale-telling kin as I’d seen them detain one another and thereby earn what seemed to be their faithful love. When I was a child, could I have explained to you any of that long-term hope for my life? No, but I honestly think I felt something very like all of it. And isn’t at least that much the burden of all my work—some thirty-seven full-length volumes to date?

In my sophomore year at Duke, I read Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and came across a phrase which perfectly defined the way in which I might manage my own vocation, the life of a writer—an instructive and broadly useful writer. It comes near the end of something Joyce’s alter ego, Stephen Daedalus, says to his friend Cranly.

You have asked me what I would do and what I would not do. I will tell you what I will do and what I will not do. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe whether it call itself my home, my fatherland or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can, and as wholly as I can, using for my defence the only arms I allow myself to use . . . silence, exile, and cunning.

As I aged and learned how Joyce’s ultimately cold heart had deadened so much of his work after the Portrait and the short stories in Dubliners (his concluding story there—“The Dead”—is still the finest I know in this language), I nonetheless kept to his motto for the inner life: silence, exile, and cunning. I exiled myself for three years—and eventually a fourth—to a country that was then very different from my own, I kept my silence about the most intimate concerns of my own heart (including my homeland’s increasingly appalling reactions to the inevitable progress of the civil-rights movement—in September ’57 President Eisenhower had sent in federal troops to insure the integration of public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas; and white townsfolk turned out to malign the young black students). As for cunning—I did what it took, short of physical harm to another, to foresee and then finish my work.

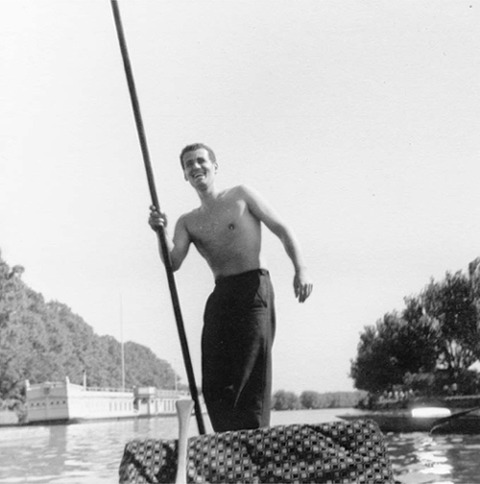

Anthony Nuttall, punting me on the river Isis (the Thames, as it passes through Oxford, is called the Isis). Propelling a punt is a thoroughly tricky bit of survival-on-the-water. What’s required is first-rate personal balance in an upright position and the strength to use a long pole to send the flat-bottomed boat onward—and all without propelling one’s self into the water or the punt in an undesired direction. Provided the punter can deploy the necessary skills; and given a beautiful day (as Tony and I clearly are), few river trips can be more enjoyable. Tony Nuttall was as fine a master of punting as he was of Greek, Latin, Anglo-Saxon, ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, ethics, and poetry and—in time—the details of English literature. After he and I had shared a year’s digs at 2 Sandfield Road in Headington—and seen each other often in my fourth year back in Oxford—we parted company amicably and eventually lost touch, though we sent occasional copies of our books to one another (we were the book-machines of our Merton generation). Then in the ’90s, the realities of e-mail brought us back together most pleasantly—long messages recalling shared memories, almost all of them hilarious. Though this picture is hardly well-focused, it preserves two of Tony’s memorable gifts—the strength of a fine torso and his ready joy in a rare splendid day as he punts the two of us beyond the last of the grand old college boathouses (themselves rotting barges, soon to be replaced by dismal substitutes). That he was buried on my seventy-fourth birthday was a shocking sadness.