17

RETURNING TO A COLD wet gray Oxford, it felt entirely natural to reconnect the battery on my Volkswagen and rejoin Win and Jack Kirkby, Tony Nuttall, a few other student friends, and of course my faculty friends—David, Nevill, and (to the cool extent she permitted) Helen Gardner. I even recall my usual failure to connect with Professor Tolkien. At least once a month, I’d be climbing into the Beetle just as I saw Tolkien heading toward me from his home at number 76. I’d always ask if I could give him a lift down to Merton, and he’d always give me nothing more than a broad grin—“Thank you kindly, Mr. Price; but I think the walk will do me good” (by the walk, he meant another fifty yards to the bus stop on the brow of Headington Hill; now that I’m older than him at the time, I understand—he didn’t want to have to make small talk with a student; and by the way, he pronounced his name Toll-KEAN, not TOLL-kin as most Americans miscall him).

While I waited for my oral exam, I dutifully began to think of what lay before me if I undertook serious work on the D.Phil.—a history of the short story in English. From midway through high school onward, I’d consumed hundreds of such stories and, in recent years, an almost equal number of the Russian, French, and German stories which had deeply influenced the best writers in English. Guided now by David Cecil—who almost literally seemed to remember every word he’d ever read, certainly every plot and character—I began more reading and rereading: the often ramshackle but generally powerful stories of D. H. Lawrence, the perfections of James Joyce, stories by Hardy, Forster, Woolf; even a few living writers like V. S. Pritchett and of course Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Porter, and Welty (I’d hardly thought yet of immersing in the brief English prose fictions that came before the nineteenth century).

Truth is, though, that while the reading was often pleasing—and occasionally exciting and instructive—by then I was far more interested in the possibilities of my own work, especially now that I was freed of the weight I’d worn for two years—poor blind shackled Samson. The surviving notes for my long story show how much time I spent that winter and spring in contemplating the technical problems of what would be my first venture into long narrative. Reading those notes so many years later, I can see how clearly I was coming to realize the degree to which the story of Rosacoke and Wesley’s relationship was beginning to absorb the core of many emotions of my own and the questions my feelings raised in my own life and in the world around me. The history of fiction famously contains many instances in which male writers have successfully invented central female characters who go on to express intense thoughts and feelings in which the author himself is profoundly invested.

Flaubert’s Emma Bovary, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and Hardy’s Tess are the most enduring such characters; and while a few feminist critics have attempted to demonstrate that these characters are unconvincing portrayals of “real” women, they’ve hardly stemmed the flood of conviction by generations of readers, female and male, that these novels—and a good many more—produce a rich sense of complex female life. Wouldn’t almost any well-equipped novelist of either gender be to a large extent psychically bisexual—as were Mozart, Verdi, and Wagner in the narrative intensities of opera?

Why that’s so is hard to define; but when I asked the question of David Cecil, he said virtually the following, “Men are reared by women; so are women. Each of us has a mother; and in almost all societies, children are raised in the essentially exclusive company of women till they’re at least adolescent. Therefore observant men learn a great deal about women before they begin to desire women sexually; female writers are put at a disadvantage perhaps because, while they’re reared by women, they happen to be women themselves and thus spend little time in the close company of men till they’re courting or married.” I can understand why some women find such an observation difficult to accept; but if they reject it, then it would be interesting to hear why they think there are so few distinguished novels written by women with central male characters. David had earlier noted in an essay on Jane Austen that, in all her novels, she has no scene in which a man is portrayed alone and in thought; and he added that she apparently doubted her ability to achieve such a moment convincingly.

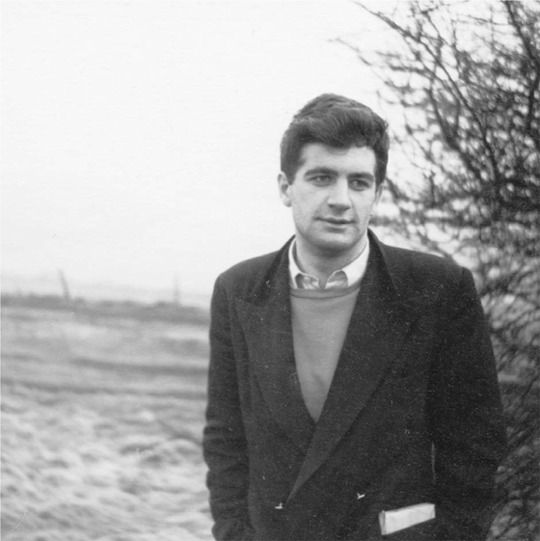

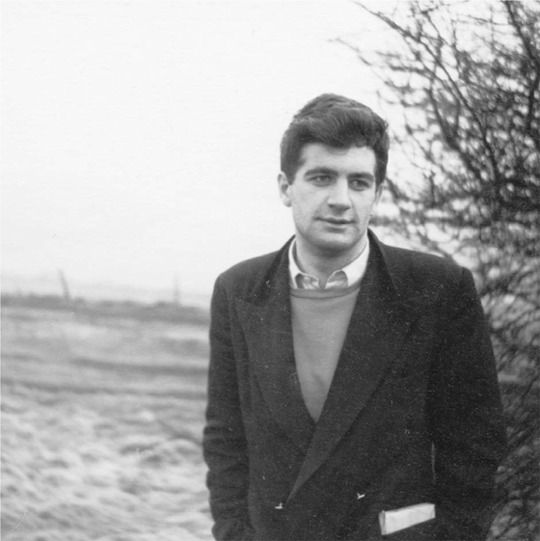

Peter Heap, early 1958, at Inkpen Beacon, the highest point at the northern edge of England’s chalk downs. The gallows that stand only a few yards from Peter in this picture were first built in 1676 to execute a man and his mistress who had, nearby, clubbed the man’s wife and son to death. When the brutal couple were hanged, it was claimed that their chained remains could be seen from surrounding counties, suspended from the gibbet. Peter had arrived at Merton a year after me; and though I was a graduate student, Peter’s two years of prior service in the British army left him only two years younger than I in his freshman year. We’d set out idly from college after lunch for a brief country ride to help us dispel winter grimness, but good talk took us farther and father onward till we wound up in Berkshire at this spot, grimmer than the weather in which I took this picture. In the years after his degree in politics, philosophy, and economics, Peter’s work in the Foreign Office would prosper; and by the time of his retirement, he was British Ambassador to Brazil. Shortly thereafter, he was knighted—Sir Peter Heap, a grateful but unexpected thing to call this cheerful old friend.

* * *

The numerous lingering events of that final term included a drive with John Speaight and Peter Heap to Peter’s family home in Bristol. I’ve mentioned Peter’s army experience, which left him with a fund of amusing memories but also the familiar English hunger for amusement from others, a hunger which renders them among the planet’s great listeners. I’ve also recalled John’s wry wit. With that gift (plus the fact that he was a perfect stereotype of the learned young man who has agreed to look funny: large ears, huge glasses, an irreparable cowlick, and a slow but winning grin), he was always a welcome companion. A few days then with two such friends, quite different from any Americans I knew—and quite different from Michael—added a helpful late set of touches to my sense of the early-postwar Englishman.

Those days in Cary Grant’s hometown (his real name was Archibald Leach, and he was born there in 1904) included visits to Bath and the nearby small city of Wells. I’ve noted my visit to York Minster and its lasting impression on me as the grandest of ecclesiastical buildings. Wells Cathedral remains for me a structure with similar irresistible power. A considerably smaller medieval space is rendered haunting by its solution, found some two centuries after the building’s completion, to the problem of supporting the weight of the tower when signs of strain began to develop. Three inverted gothic arches were introduced at the crossing which bisects the altar; and the resulting solution to a potentially disastrous problem is not only ingenious but entirely original and ultimately a witness to an initial human failing that was met with a practical imagination that ended in startling beauty.

* * *

The remaining crucial event of those last months in England was the eruption of a first quite fervent erotic relation, this one with a man eight years my senior. He taught elsewhere in the university, and I’d met him on several relaxed social occasions early in my third year. For honorable reasons that I won’t spell out, he’d been separated from his family in Eastern Europe, had spent hard months in a prisoner-of-war camp, and had reached Britain soon after his liberation (by then his home was in Soviet hands). The experience had not only all but starved him, it was my eventual sense that it left him with intense emotional hungers and a baffling fear of feeding them.

For whatever reasons, he seemed to fend off his obvious needs. Nonetheless in some thirteen prior years, he’d worked his way up the formidable British academic ladder to a safe position. Yet I was far more drawn by a physical appearance that distinguished him, in any room, from even the most striking nearby Briton. In his strong head and face, I aroused my attraction by assuming—maybe rightly—that there was a whiff of genetic memory of the passage of Attila and his Huns through medieval Europe. In any case his appetite for long sessions of philosophical conversation could grow complicated by his insistence on dominating a round of exchanges—there was a genuine air of the warrior about him—yet he laughed often, if a little reluctantly, when sufficiently entertained; and his spoken English was perfect, though firmly accented.

After we’d talked at a couple of student parties, we began to meet for dinners, movies, and country drives—trips on which I was soon giving my second round of Oxford driving lessons. Soon I could hear the familiar sounds of a strong magnetism clamping down on my mind. His name was Matyas and in late February he invited me to join him on a trip to London for a luncheon with Sir John Gielgud—he’d met the great actor a year or so earlier. It was a small party in Gielgud’s narrow house on Cowley Street just behind Westminster Abbey—four guests in all, I think, including the young actor Brian Bedford who’d been Ariel to Gielgud’s recent Prospero in a London production of The Tempest (which I’d seen with another Oxford friend).

There was excellent food served by an all-purpose butler; and of course there was much laughing theatrical talk and banter followed by coffee upstairs in the sitting room where a beautiful, perhaps Pre-Raphaelite portrait of Gielgud’s great-aunt the actress Ellen Terry in her exquisite youth, hung over the fireplace (I’m unsure whether it was by Millais or by her first husband G. F. Watts). I was agreeably surprised by the fact that, as we all sat—eased by modest amounts of midday wine—Gielgud began calmly to tell us about his notorious public shame only four years earlier.

There’d been no comparable scandal in the upper reaches of the British theatre since the trials and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde half a century ago (and Gielgud had been the peerless actor in postwar revivals of Wilde’s comedies). Sitting in the warm safety of his home, hearing an eminent artist describe a personal disaster—and no later account that I’ve encountered contradicts it—we learned first that Gielgud’s knighthood had apparently been delayed by the government’s fear of his discreet but well-known homosexuality. Olivier, who was three years his junior, had been knighted years earlier, as had Ralph Richardson; and Gielgud was arguably their superior, certainly their equal. But in the swirl of artistic events and honors that attended the coronation of Elizabeth II in the summer of 1953, Gielgud at last became Sir John.

Then early in the fall, he was arrested for importuning a plain-clothes policeman late at night in a men’s room in Chelsea. I recall only one thing he said about that moment of entrapment. He smiled slightly and said “I looked at the gentleman standing there and said to myself ‘Not my type.’ Then I told myself ‘Who am I to say “Not my type”?’” Since no physical contact occurred, the punishment was merely a small fine rendered in a magistrate’s court a few hours later. The significant punishment descended in a flood however, as news reached the papers.

In recounting the story to us—four younger men, only one of whom I knew—our host focused on the immediate aftermath of the revelation, as he returned to his Cowley Street house alone. In Sheridan Morley’s authorized biography of him, Gielgud says that his first thought was suicide. I doubt he told us that. What he did say, without an audible trace of self-pity, was that—when the early edition of the Evening Standard hit the streets—he waited and waited for the phone to ring. Where were all his friends from the highest echelons of theatrical life? None of them phoned, though he did allow that “Many of them, to be sure, were likely still asleep.”

At last Dame Sybil Thorndike—the elderly doyenne of the British stage and Gielgud’s colleague in an immediately forthcoming play—phoned sympathetically and refused to hear of his not attending that evening’s rehearsal. He went, the scandal mounted to hysteria in some quarters; but he somehow survived and continued, not merely in A Day by the Sea but in the succeeding months. In Gielgud’s after-lunch account, there was a coda that tasted a little bitter after his report of Sybil Thorndike’s kindness.

Shortly after the play opened, the Queen Mother Elizabeth was scheduled to attend a performance. Just before the play began, the stage manager entered Sir John’s dressing room and asked if he’d please send the Queen Mother his regrets and not appear with the remainder of the cast when her Royal Highness came back to greet the actors (she was, by the way, known for liking queer men). Having no wish to embarrass a royal, Sir John of course sent a polite message—he was physically indisposed. When the great lady had said all her greetings, however, she turned to the bumbling stage manager, handed him her armload of flowers, and asked that they be taken as soon as possible to Sir John. And they were (the word bumbling is my own; Gielgud did not characterize the little man’s timorousness).

The entire account of his humiliation can have taken no more than twenty minutes before he smiled again and stood to offer brandy. If I ever knew, I no longer recall why Sir John chose to tell us—surely none of us asked him. Reading Sheridan Morley’s careful chapter on the episode and its lifelong effects on a man of such distinction, I can imagine at least that Gielgud was unburdening himself of a heavy weight (he hadn’t mentioned that his mother was alive at the time of his shame). With how many others in the London of 1958 could he speak of the episode? Perhaps even more important, he was offering us, his young guests, a serious warning—a by no means uncalled-for warning.

John Gielgud, who shared eminence with Laurence Olivier as a classical actor on the British stage of the late twentieth century. I saw him in King Lear, The Tempest, and in Graham Greene’s The Potting Shed; and among several meetings, I spent an extraordinary afternoon with him (and a few others) in his London home near Westminster Abbey in the winter of ’58. This studio photograph, from 1961 by Jeremy Grayson, captures his famous profile with the imposing nose which he always called “the Terry nose,” a gift to caricaturists. Through his mother, Gielgud had inherited the genes of the Terrys—an enduring English family of distinguished actors, including Ellen Terry, Sir Henry Irving’s partner through decades of distinguished Shakespearean performances (Gielgud was her great-nephew).

Morley gives considerable evidence for thinking that the British police of the early to mid-1950s were engaged in an all-out assault on homosexual behavior, perhaps exacerbated by the arrest and conviction in 1953 of Lord Montague and three of his friends for alleged relations with two airmen. I can’t speak to the possibility that Gielgud was implicitly warning us; I don’t recall hearing any warning from him (nor from any other queer friend at the time). Morley spells out in painful detail the degree to which Gielgud—despite the enormous successes, especially in films, of his later years—was forever blighted by his arrest and left unwilling to discuss it, or his own sexuality, publicly however widespread the awareness of homosexuality became in the decades before his death.

What I do know is that, after all these years, those quiet minutes—in a thoroughly private space—are the only time I’d yet heard an unquestionably great artist (and a great man) uncover the core of a personal tragedy. My gratitude is still considerable, for the trust involved, reckless as it might have been. I was after all a stranger, brought to his home by a man whom he hardly knew. We might have abused his confidence and caused him further embarrassment. What I’ve brought forward here, seven years after his death, is plainly meant by way of praise (and while my relation of Gielgud’s private account differs in a few minor details from Morley’s, I confirm my own memory).

* * *

For some time John Craxton and I had harbored vague plans to drive to Cornwall and take a boat out to the Scilly Isles. After another trip to London during which I introduced Matyas to John, back in Oxford I urged Matyas to make a party of three with me and John in the islands during the Easter vac. The Scillies were scantily inhabited then, not the tourist resorts they’ve since become; and John had stayed before on the island of Tresco with a warmhearted fisherman’s family—the Bill Gibbonses—in their small cottage. Matyas pled hopeless busyness but at last agreed, so John made the arrangement with Cathy Gibbons; and though Matyas tried to cancel at the last minute, I laid siege for his company and prevailed.

John joined us in Oxford, and early one morning we set out for Cornwall—Penzance and Land’s End—in gloomy damp weather. At the time I was the only one with a driver’s license, so I manned the wheel one whole long day and night on a good many two-lane roads that were even more excruciatingly slow than usual. Still we made only occasional stops for pub food, toilet calls, and stretches. We were aimed for an early-morning mail-and-supply boat that ran every few days from Penzance to the islands, and we just made it—parking my car in a waterside lot and boarding the boat almost as it pulled away from the dock (how could I trust that my much-loved Beetle would still be there when we returned?).

The crossing lasted for a turbulent three hours as we entered the Gulf Stream that flowed north past Land’s End and rendered the Scillies not merely the westernmost outpost of Britain but quasi-tropical in their climate, by comparison with southern England at least. Matyas managed to sleep on one of the small boat’s inside cushioned benches. John and I spent most of the time on deck, absorbing the chill spray and waiting impatiently for the first glimpse of the islands. At last the boat beached us and our slim luggage unceremoniously on Tresco, and John led us toward our lodgings. The walk took us past the island’s lush garden adjacent to the local manor house and chocked with almost alarmingly healthy palm trees, large cacti, and various other entirely unlikely seeming plants for such a latitude.

Our hosts and their children met us with an equivalent warmth. And a fine ten days commenced—lots of reading, naps, walks round the mainly empty island: a few more cottages, a tiny village center with a post office, and one or two miniature shops, a small church, and numerous areas of shoreline that would have been ideal for swimming had the early spring water not been dauntingly cold (Gulf Stream or not). Otherwise we had one another’s affable company and Cathy’s good plain food—huge breakfasts, elevenses, lunch, high tea, and a big supper which was always centered on whatever fish Bill brought in from the sea that afternoon. I recall that he returned once with a fresh-caught bucket of anchovies—small long silver fingerlings. Kathy boiled them up quickly, mashed them into a kind of butter, and served them with our tea on her homemade bread. I think I heard, years later, that Bill had drowned at sea.

In the attic room of the cottage, I had also the fulfillment of my main hope in the trip. Matyas and I turned our prior uncertainty into an actual intimacy. Despite the fact that I’d turned twenty-five in February, it was my first experience of employing my body in one of its grandest jobs. There was, in a single important sense, no future for the acts in any true marital way (we could obviously propagate no children); and since I’d be departing for the States in June, our acts—however expressive of desire and affection—were hardly likely to be one of the main fuels of an enduring love. But as I already knew, any form of physically harmless sexual union between willing adults may well breed—literally—a number of good things. My writing had already greatly benefited by a few such affections; and the heated relation which Matyas and I chose to begin on Tresco would likewise prove fecund in very different ways (sex between two men is, in one pure sense, the ideal male sex act, productive of possible affection and a quick intense pleasure—an act that’s therefore profoundly different from female sex, likely as that often is to result in the commencement of a child’s life).

And when I speak of fecundity, I’m not at all suggesting some vaporous metaphysical ecstasy—some seventeenth-century fantasy of souls uniting in midair above the bed, the grass, the sandy verge of an ocean beneath the little flesh with which I’d so far joined. What I knew by the spring of my third year in England was the vital relevance for me of intimate union, not only for its powers of simple invigoration through the heights of physical pleasure (with accompanying talk and laughter) but also for my own adult self-respect and the ongoing growth of my work. That pleasure affected deeply the rhythmic vigor of sentences on a page as they attended closely to the precise moral implications of my subject at any given moment in my story. The fact that the unions I longed for were then gravely illegal—in Britain, through much of continental Europe, in the States, and most of Asia—was a fact that hovered at the edge of my awareness of a powerful need; but I was hardly deterred.

Even when love was out of the question—love in the sense of a relation that’s likely to endure, ripen, and alter with the decades—my realization that a sane and mainly admirable creature was desiring my body (and outright using it for his own purposes) helped me award myself at least a minimum of self-esteem. And that’s a quality which I, like most everyone I know, am generally a quart low on. I don’t think I’ve been much of a self-hater, though my adolescence had the usual stretches of in-turned self-consumption. Neither have I often stood before any of the available mirrors and preened in the glow of my imagined perfections. But my reflection, through the years, in the eyes of a sane lover—sane and not self-loathing—has taught me considerable amounts about my deplorable qualities and failings and has likewise encouraged me to shore up whatever genuine benevolence is left in my soul.

* * *

Through my remaining weeks in Britain, I packed in all I could while still pursuing the excitement of knowing Matyas (he no longer gave serious signs of resisting my aim). I also kept a steady amount of reading under way. I saw as much of David Cecil as he and I could manage. I worked on my notes for the pregnant-girl story, and I learned a great deal from a small passage with Nevill Coghill. In the post-Christmas weeks, thinking that Nevill might well be one of the three oral examiners of my thesis, I avoided the friendly evenings we’d become accustomed to having—in Oxford, Stratford, wherever. Eventually he sent a note and asked if he’d somehow offended me. He likewise invited me to tea. When I went, he asked again about any offense he might have caused; and I explained my recent disappearance—I didn’t want to press my friendship to the fore in any decision he might have to make on my thesis. He heard me out, frowning; then smiled his tooth-filled grin and said “But Reynolds, you’ve been my honored friend for nearly three years. You don’t think that if your thesis were poor, I’d fail it, do you?”

If anyone had asked, I’d have denied possessing any shred of whatever Protestant Puritanism might lie among my origins; but no, here and now I was momentarily shocked by Nevill’s question. Smiling though he was, I could hear that he was dead earnest; and suddenly I realized that what he said had been clarified in a sentence I’d encountered in an E. M. Forster essay—“If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.”

My own later years of teaching, and life, have sometimes left me unsure of my total agreement with either Nevill or Forster (though when I insert the word mother, father, son, or daughter, then disagreement would prove impossible); but sitting on the other side of a Coghill family teacup, I’d glad I thanked my friend for his brave and instructive wisdom. (Years later I read about the 1980s revelations of treason among a group of Cambridge faculty and students—spy activities involving the betrayal of British and American military secrets to the Soviet government—and then I’ve had even more complicated situations in which to test Forster’s maxim: one of the notorious Cambridge spies, for instance, was later a firm friend of mine, though I scarcely knew of it till after his death.)

In mid-February 1958, Nevill indeed proved to be one of my examiners—the other two were strangers—and at the end of a lively hour-long viva in the lobby of the Examination Schools, all three of them approved my thesis with no apparent pressure from my loyal friend. I was an unofficial Bachelor of Letters; the official award would occur in a begowned ceremony in Christopher Wren’s Sheldonian Theatre later in early May. I’d made my return, however belated, on the generous trust of the Rhodes Foundation, my teachers thereabouts, and my kin and friends at home. Further I’d proved to myself that I could stand in countervailing winds, most of them self-generated, and complete a job that had grown increasingly baffling for me—baffling in the sense of Why should I be doing this? But now—whether or not my high-school decision to pursue a lifetime of writing and teaching would prove feasible—much remained to be seen.