18

IN ANY CASE I’d celebrated my first professional publication in March of ’58 when Encounter published “A Chain of Love.” It was a long story for any magazine, and it won a good deal of attention to itself. My Oxford friends and teachers were especially responsive, the BBC’s weekly magazine The Listener (whose literary editor was the distinguished writer J. R. Ackerley) took brief note of the story, a rare form of praise; and responses from the States included an offer of a contract for a book of short stories from Hiram Haydn, the famous editor in chief at Random House. Diarmuid recommended immediate acceptance, though he’d declined Cass Canfield’s from Harper’s. Hiram’s offer came with a five-hundred-dollar advance—serious riches in comparison to my recent bare fortunes. After the slow progress of my academic life, my literary life felt suddenly transfused with high-class hope.

* * *

It’s clear, I trust, that what remained of my three-year residence in one of the Western world’s most distinguished and venerable universities would hardly be spent in academically intense pursuits. A considerable amount of time was spent with Stephen—and in a hard period of his life. Through a good deal of ’57–58, he’d been attending various maddeningly pointless cultural conferences, especially in Japan. It had been his first visit to that opulent and almost incomprehensibly contradictory culture; and while there, he’d met a young man in whom he’d rapidly invested a great deal of emotional energy.

The man, Osamu Tokunaga, had likewise quickly attached himself to Stephen; and in Stephen’s letters to me and in our later conversations, Stephen made it clear that he himself was in a personal dilemma. There were two problems—he felt an intense attraction to Osamu; he also felt that his home life was becalmed. From what he told me—and from the fact that he made a second trip to Japan on the heels of the first—I began to feel that only the youth of the Spender children, and the necessity of making the money to support an estranged family, was restraining Stephen from a drastic new arrangement.

Given the fact that we’d met little more than a year earlier, I was complimented by the trust Stephen seemed to place in my advice (I see now that he had few older confidants for such a crisis, perhaps only Isaiah Berlin who stood high among respected British intellectuals of the time). I was still twenty-five; Stephen would soon turn fifty. I hadn’t then grown as familiar as I’ve since become with a Western middle-class male tendency to midlife crisis—what I’ve since had reason to believe is a true male menopause (probably a psychic rather than a physical change; I know—I eventually had one). In any case I’d never met Osamu; but I was compelled to tell Stephen that, quite apart from the inescapable nature of his family commitments in England, his persistent thoughts of a future with a young Japanese man—perhaps even life with Osamu in another country—seemed to me hopeless.

I doubt I added the other relevant words, reckless and cruel to everyone involved, himself included. I could see he knew them better than I and recited them many times an hour. Still, he agonized for months; and as the next ten years would play out in Stephen’s life and work, the brief confusion surrounding Osamu seemed a major forecast of the humiliation attendant upon Stephen’s confirmation of rumors whose roots he’d pursued for years—the possibility that the CIA was in fact the principal founder and continuing support of Encounter, a support whose admission many of his far-left friends and enemies had urged upon him well before he at last believed it.

Whenever Stephen was in England, I’d drive to London for more lunches or dinners and evenings at the theatre. We saw, for instance, Graham Greene’s The Potting Shed with John Gielgud and Irene Worth, a mediocre play and a good performance marred by a smattering of audience laughter when Gielgud’s character began asking questions on the order of “What can be wrong with me?” At that time, for professional reasons, Stephen was seeing a good deal of Irene Worth, a native of Nebraska who’d succeeded in the British theatre (he was then translating Schiller’s Mary Stuart for Worth); and I joined the two of them in several talkative dinners, at one of which I confronted my first boiled artichoke—the culinary equivalent of encountering your first fried Gila monster: how do you approach it? Worth’s friendliness was always, and often tiresomely, laced with the standard actor’s fury—in her case, at such-and-such an acting colleague or director. She could well have used an awareness of Helen Mirren’s later remark about herself—“I’m famous for being cool about not being gorgeous.”

I’ve noted that Stephen and I heard Joan Sutherland in Meistersinger. Before the spring was over, my Merton friend Jeremy Commons took Stephen and me to hear Sutherland again, this time in Handel’s Alcina in St. Pancras Town Hall (as I remember). Handel had long been among my prime composers; and Sutherland herself sang memorably, without the mannered drooping diction that would spoil so much of her later work. But several of the surrounding cast were amateurish, and the sets were minimal (Jeremy would later become friends of Sutherland and her husband Richard Bonynge; and though he returned to his native New Zealand to teach, he’s managed to work frequently with Bonynge on textual and historical questions relating to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century opera).

In those last months I relished Wystan Auden’s annual visit—his usual superb lectures and a hilarious evening when I hosted a four-man dinner at the quiet Tudor Cottage in Iffley. Apart from Auden, the guests were John Craxton and a friend of his called Brin who’d come from London for the occasion. Brin was an Irish country boy and a member of the Queen’s Irish Guards, quartered in London. Possessed of a recognizably Celtic gift for tale-telling, Brin regaled us with stories of the means whereby many of the Guardsmen—miserably paid as they were—scrounged a fair amount of spending money by making themselves available for sexually active evenings with well-to-do male civilians whom they met mostly in pubs around Piccadilly Circus. His best story—and I can tell it here because Brin died many years ago—involved his beginning an affair with a well-known American film director whom he met in Hyde Park (decently, he declined to give us his name).

The director was then making a film in London; he and Brin began at once to meet for sex. Soon the director introduced Brin to his wife; and in short order Brin and the wife were meeting for their own intimacies. Brin assumed that these encounters were secret from the husband; but when the director completed his film, he invited Brin to a dinner in the couple’s hotel suite; and as the climax of the evening, the director and his wife jointly presented Brin with an engraved gold watch which made it quite clear that both husband and wife had, at some prior point, learned of one another’s meetings with Brin.

For me, it was a fascinating glimpse of a wholly new world when I realized that this Irish country boy, born into grim poverty, saw all such meetings—the one-on-one Piccadilly dates and the involvement with an American couple—as exhibits in a personal and highly comic Vanity Fair. Yet for all the comedy, and its pictures of human beings at their most helplessly abandoned to desire (a state about which I’d lately learned a fair amount), Brin anointed his accounts with a patently genuine degree of affection. He had clearly felt some degree of understanding of his clients’ needs and had been glad to be of service. Even his account of evenings with “the Mad Major,” whose exotic requirements I’ll spare the reader all knowledge of, was astounding but accompanied by Brin’s quiet chuckle. His short strong body and cheerful face were among the few possessions he could offer an interested world (he had a steady girlfriend, all the while—a Cypriot, I believe).

* * *

Late in the spring term, David Cecil gave a small dinner in his rooms in New College—six guests. Auden was guest of honor, and the others were undergraduate writers and perhaps John Bayley. This may have been the occasion on which I met Julian Mitchell who’d later become a successful writer of plays, films, and novels. Years later he’d visit me several times in the States and become a close friend. John Fuller, the poet, was likewise present; and the evening went ahead pleasantly—late sunlight poured through the windows—with a good deal of good-natured jokery.

As we neared the end of the wine and poetry, Auden lifted his head a little backwards—a sure sign, I knew by then, that he was about to deliver either a serious Auden dogma or a witticism. He then proceeded to tell us that he was proposing an emendation in Milton’s supreme pastoral elegy “Lycidas.” In the penultimate line, the traditional text of the poem has always said (and I give it in its seventeenth-century spelling; the word spelled blew is our word blue)—

At last he rose, and twitch’d his Mantle blew;

To morrow to fresh Woods and Pastures new.

“I’ve always suspected,” Auden said, “an error in the line; and I propose the insertion of a semicolon after the word twitch’d.” He then stood in place, gave an exaggerated twitch of his head, swept an imaginary mantle behind him with a broad wave of the hand, and began to say his goodbyes. I took the joke as a reference to my Miltonic interests. It was also clearly an adolescent textbook-Auden parody of the donnish absurdity he’d been teasing (however quietly) since his return to Oxford. We all stood, laughing, to see him off—tottering a little dangerously as he descended David’s stairs, entirely alone in the still-bright early summer evening.

A further deep look into Auden’s nature came at the end of term when he asked if I’d drive him and his sparse luggage to the station for his train to London and thence to New York. When I went to collect him from his rooms in Brewer Street, I asked him to sign a copy of his collected shorter poems. He signed himself “With love, Wystan Auden” which touched me—I hadn’t expected so much. But as I stood waiting, I looked round at two rooms in a state of disarray that I’d never before seen generated by any human being. And Wystan had only been in residence for two months. The desk, the floors, the tables, and every other surface were inches—if not feet—deep in abandoned books, magazines, clothing, galley proofs, dirty dishes, whatever. My face may have betrayed my literal shock; but Auden only gave a brisk wave above the chaos and said “If you’d like to come back later and see if there’s anything you want, by all means do” (in those days Oxford rooms were almost never locked).

I drove him to the station, sat with him there in the gloomy café for a heavy mug of tea and twenty minutes of the very one-sided talk I’d always had with him—friendly on his part but entirely self-centered. Toward time for the train, I asked if he had any advice for the start of my teaching career; and rather surprisingly he said that if I felt attracted to any of my American students I must be especially careful in arranging private meetings. He expanded by saying, as I recall, “An English or European boy will politely decline an invitation if he suspects that a pass is likely to be made and is sure that he’ll wish to decline. A young American may knowingly accept the invitation, then appear surprised and even shocked at a pass.”

I nodded my bemused thanks for the information, then helped him and his tattered bags aboard the train. Straight afterward I returned to his rooms as he said I might. In the end I couldn’t bring myself to look for long through the indescribable and, in places, filthy mess. I collected two or three paperback books with penciled notations in his near-illegible hand, then abandoned the job. If I’d had more patience, I could likely have gathered a hundred pounds of lucrative items for future years but, foolishly, no.

As I left I wished only that I’d brought my camera, if only to have future proof of this great poet and critic’s potential for private disorder (later I read of Beethoven’s own notorious shambles in his frequently changed Vienna lodgings, the only parallel I’ve since heard of to Auden’s chaos). How does the mind of a genius—and Auden was the single unquestionable genius I’ve known—function in the midst of such external confusion? He’s known to have said he hated the self-generated havoc but found it inevitable; and it seems to have accompanied him throughout his life, wherever he paused for more than a day. Stephen was bad enough—when he left at the end of any stay at my home, I’d spend half a morning collecting his left-behind clutter; but compared with Wystan, Stephen was obsessively neat.

* * *

In the bright warm weather of May and June, Matyas and I continued our relation with trips to London to see the Moscow Arts Theatre in Russian-language productions of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya and The Cherry Orchard. I read the plays carefully again before seeing them; and the performances were so splendid that I had the illusion, throughout, of understanding every sentence—if not every word. Back in Oxford we took long country rides (Matyas would soon be ready for his driving test); and we sometimes shared our delight in each other with the clouds and weeds. Such sharing was hardly wise, considering that male-male contact was still punishable in Britain by substantial prison time. And though the famous Wolfenden Report had appeared the previous year, recommending that sexual contact—in private between consenting males over the age of twenty-one—should be decriminalized, it would be another ten years before those recommendations became law and another forty-three years (in Britain) before the legal age was reduced to sixteen, the same as for heterosexual acts.

Before those weeks I’d been a thoroughly private man. Now, though, I carefully filed away mental images of places where physical delight reached memorable heights for Matyas and me. There was one particular Sunday afternoon on a flank of Boars Hill. The hill was a sedate but still-posh Oxford suburb, the sometime residence of distinguished turn-of-the-century poets and scholars. Robert Bridges, the poet laureate who’s now remembered mostly for having edited and published the great poems of his college friend Gerard Manley Hopkins, had lived on the hill for many years and died there in 1930. Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who either discovered or invented (as some scholars believe) Minoan culture in ancient Crete and published an exhaustive four-volume account of his findings, had survived till 1941. And Gilbert Murray, who’d long been the presiding scholar of Greek literature, had survived till almost exactly a year before the day I’m describing.

Bridges died at eighty-five, Evans at ninety, and Murray at ninety-one. In my own time there, yet another poet still lived nearby—John Masefield—and Nevill had recently told me of a visit to the old man. As tea ended and Nevill rose to leave, Masefield handed him a small new volume of poems. Nevill had not heard of their publication, and he expressed surprised pleasure. Masefield said “Ah yes, you see I’m like an old clock. My hands have fallen off, and no one tells time by me anymore, but I go on ticking.” So he did—to almost eighty-nine.

Yet for all the hill’s placid suburban air, even in the Fifties it harbored wild fields covered with new summer weeds and their various flowers. Matyas and I laid ourselves down there on a particular warm Sunday and took the nearest we could come to full pleasure in sight of the sky and anyone who might have happened to pass. In those high-class purlieus, no one seems to have done so, though I’ve wondered more than once if there could be a snapshot lurking in an aging box of someone’s scraps, recording the moment of two young men far gone in gravely illegal affection. In any case, there’s a vivid picture in my own skull still, safe behind my good eyes.

* * *

Not long after, I drove Matyas north to St. Andrew’s, the Scottish university where he’d agreed to serve as an examiner. We proceeded as speedily as we could manage on the highways of the time till we landed in a handsome seaside town. While Matyas examined students nearby for several days, I roamed the town’s lanes and numerous bookshops in surprisingly balmy weather and ate my take-out pub-sandwich lunches among the ruins of a medieval cathedral. Then when it was clear that Matyas would need more time for his local job, I turned back toward Oxford.

On the return I felt so sad to be alone that I paused on the long slow trip only for gas. I even sped past the tourist-hallowed sites of Wordsworth and the other Lake poets, and I was a man—still am—who revered Wordsworth second only to Shakespeare and Milton. The eventual dizziness of hunger did stop me once somewhere in the grimly industrial Midlands for a truly ghastly meal in a laborers’ café. When I entered and sat, the locals and the waitress were loudly enjoying themselves; and I seemed to be invisible to them. Only when I indulged in a loud stage cough did the waitress step over, tell me that there was still toad-in-the-’ole; but “All vegges are off.” I usually enjoyed such surroundings; but now I could only bolt down the barely warm meat pie and return to the road, aiming to reach my own narrow bed before another dawn. I was not only dead-tired but likewise on the outskirts of falling in love.

Compelled as I was, by the time I’d threaded my way through Coventry I knew I was dangerously exhausted. I’d already fallen briefly asleep at the wheel more than once. When I was back in the countryside then, I pulled into an apparently unoccupied clearing surrounded by dark trees. It was nearly one a.m. I locked myself in the car and slept for maybe three hours—dream-harried sleep—till an unnerving nearby sound woke me—gentle England had never seemed so threatening, and I drove back onto the highway.

* * *

A little later still, once Matyas returned to Oxford, and learned that I’d never seen Cambridge (Oxford and Cambridge seemed then as psychically far apart as Moscow and Cleveland), he insisted that we go there for a weekend. We drove over then, in more fine weather, to see welcome sights in a small but majestic university town that’s famously more distinguished for its writing alumni than Oxford (Cambridge taught a quartet of the supremes—Spenser, Milton, Wordsworth, and Tennyson). Oxford had harbored more than one great writer—Walter Raleigh, Philip Sidney, John Donne, Samuel Johnson, Matthew Arnold, Lewis Carroll, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oscar Wilde, Auden, and Philip Larkin among them—but it’s specialized in philosophers and statesmen (the joke has long held that Oxford excels in prime ministers because the schedule of trains from Oxford to London is far better than that from Cambridge).

I was glad to take us through Milton’s small college—Christ’s (which I’d never visited)—and from photographs I’d seen, I was able to point out the traditional site of Milton’s room. We had the compulsory outdoor tea in the Orchard in the nearby village of Grantchester; then back to Cambridge in late afternoon where, on the sidewalk, we ran into—of all people—John Gielgud who was also in town for a quiet moment. The meeting was so unlikely that I wondered briefly if Matyas had somehow arranged it; but that was past belief. And surely Gielgud hadn’t followed us there. Britain was, after all, a country smaller than many American states; such coincidences were inescapable.

We had a drink with Sir John in a nearby hotel bar (by then I was calling him John at his insistence); and despite his lordly countenance—suspended round an enormous but imposing aquiline nose and the world-famed cello of a voice—his gossip and theatrical anecdotes were as likable in Cambridge as in his own home. He said he’d be playing Cardinal Wolsey in a soon-opening Old Vic production of Henry VIII; we must be his guests. It was an invitation we hoped to accept (I’ve mentioned seeing both his Lear and Prospero earlier).

To have seen Gielgud in both those roles and Olivier in Macbeth, Titus (three times), and Malvolio in a span of three years was a theatrical and literary privilege of as high an order as I could imagine—a privilege impossible in subsequent decades. Their Shakespeare was twentieth-century university-trained in its accents and physical effects, though Olivier was more of a stage gymnast (to the point of flash exhibitionism) than Gielgud whom Kenneth Tynan once called “the world’s greatest actor from the neck up.” And of course no one really knows how Shakespeare’s own actors pronounced his lines; but the large-minded grasp of the two men’s imposing intelligences, the eloquence of their quite different voices, and the power of their gestures and general body-movement was incomparably memorable.

I’ve noted the genuinely unnerving power with which Olivier portrayed the slow crawl of pure evil across Macbeth’s soul and, eventually, that soul’s physical face till the actor’s very eyes and hands seemed splotched with the same lethal, and contagious, fungus—even ten rows from the stage, I felt endangered. And the appalling strength of King Lear’s too-late denunciation of his wicked daughters in Gielgud’s portrayal, the near-comic tragedy of his night in the storm on the heath, and the pathos of his final recovery, his begging pardon from Cordelia, and his pitiful death were at least as potent as Olivier’s other interpretations and far more so than the television film which Olivier made so late in his life that memory fails him in numerous spots, as does the power of his voice. Since Shakespeare’s death in 1616, there can have been very few times—if any—when the English-speaking stage has offered two such actors, who were simultaneously at the top of their form, for the supreme tragedies of the language and were eager to portray them in theatres.

* * *

Soon after Cambridge, Matyas busied himself with plans to revisit his birthplace for the first time since his imprisonment fourteen years earlier. He’d be gone from Oxford all summer; and by the time he returned, I’d be back in the States, teaching my own first classes. As he launched those homeward preparations, I knew I was in love; and while Matyas didn’t seem as emotionally involved as I, he’d nonetheless expended a great deal of affection—as well as physical intensity—in our times together.

I understood that his career was established in Britain and that his whole life was anchored there (he’d had occasional affairs with other men and women well before I appeared). But I had no intention of attempting a long-term Oxford career of my own. Still I was young enough to think that somehow our relation could go on growing as we parted, deepening to the point at which we might each become the other’s chief emotional commitment. Academics, after all, get long vacations; and surely we’d be able to see one another.

Matyas’s emotional life seemed to me, as I’ve said, cored out by his imprisonment in late adolescence and then—after his liberation—by an inability to return to a family trapped in the Soviet East. Now I’d come to believe, however unrealistically, that I might begin to offer something like a long repayment for his years of emotional deprivation in a frozen-up postwar Britain. Whatever my hopes, I was rational enough not to express them aloud to Matyas, even when I drove him to London where we spent another two days together before his flight east. We made an attempt to accept Gielgud’s invitation to see him in Henry VIII. By phone he told us that the particular performance we’d hoped to attend was sold out and that his house seats were already committed. But he asked us to join him in his dressing room at the Vic before the play, by which time an opening might have developed in the theatre’s very limited space.

* * *

We sat in his tiny dressing room then as he made himself up for the overweening Wolsey, then stripped to a jockstrap and donned the cardinal’s voluminous (and very hot) scarlet robes. Watching a friend—even a new friend—slowly become someone else before my eyes was like nothing I’d experienced. At last a messenger tapped on John’s door to say that even the theatre’s standing room was now overcrowded. John said that he’d gladly speak with the stage manager and perhaps we could watch from the wings; but in fact he didn’t recommend it, especially for such a long evening and with so many bulky costumes passing in and out beside us.

We bade the kind man goodbye. He left for the stage in full regalia, and Matyas and I went out for our last night together. I’d encounter the peripatetic Gielgud once more before I left England, in the Randolph Hotel in Oxford when John Craxton was in town. Again, over drinks, he was prepossessing and funny in his uniquely distant way—warm, but warm from behind a perfectly polished glass screen (by the way, I never saw him indulge, even for a moment, in camp tones or gestures; and I never heard him drop one of his notorious sarcastic bricks—perhaps they were reserved for other actors). After that, I never saw him again, not face to face—though his belated decision to have a film career gave me numerous chances to see him again and again on screen, never more brilliantly than as Charles Ryder’s father in the TV production of Brideshead Revisited.

I no longer know all that Matyas and I did for the rest of the night. I do recall that his plane was due to depart early next morning, and each of us finally slept very deeply. My eyes opened though, just at dawn; and I lay in our narrow bed, preparing myself for another farewell. By then at twenty-five, I’d reached the age when (as I’d read) catabolism likely begins—the human body’s slow decline. And I’d said more enduring goodbyes than I liked, so I knew no real preparation for the sadness of another such farewell was possible but I braced myself.

And what I recall considering then, and for some days to follow, was the unaccustomed word rapture and its role in my life for the past few months. The English word derives (as rape does also) from a late Latin word for “seizure” or “seizing.” In the best of my unions with Matyas, I’d felt seized away—not by anything so simple as a form of physical gesture, certainly nothing with a hint of sadism. What I’d suddenly discovered was a synonym for rapture—with little doubt I’d tasted ecstasy (which derives from Latin and Greek roots meaning “standing outside”).

In the initial delights of plain physical nearness and the ultimate release, I’d frequently begun to feel outside my body’s and mind’s concerns—and for more than a few postcoital minutes. It seemed, then and now, a blessed acquisition; and like most forms of intense pleasure, it would ultimately lead to spells of dependence—a gratification most fully described in “The Closing, the Ecstasy,” the final poem in my Collected Poems, one written long after my first Oxford years and after actual paralysis had seized me.

Then a porter knocked to alert us. We shaved, dressed quickly with few words said, ate another inescapable breakfast; and I left Matyas at the in-town terminal for the bus to Heathrow. As he passed through the gate, I thought he seemed bereft of a great deal more than me (though in a few years he’d have a fine wife and likable children). By then my Beetle could virtually drive itself back to Oxford; so I set it on its invisible rails northwest and was on Sandfield Road again in hardly more than an hour.

* * *

The final days of those three years are a blur of packing and further goodbyes. I called on David Cecil in his home for a late-morning sherry. I’d been to his family home on Linton Road many times before, but I’d never quite noticed two revealing things. First, despite his family’s wealth, the house in north Oxford was much like the homes of a number of my teacher friends in the States (good furniture, good pictures; nothing ostentatious, though Glyn Philpot’s profile portrait of David as a young man was all but Edwardian in its muted Yellow Book flamboyance—I recalled that David had told me he’d been fascinated, during the sittings, by the fact that Philpot actually wore a gold earring). Second, David’s study—where we usually met—was upstairs among the family bedrooms (I’d met young Jonathan, Hugh, and Laura); and I sometimes made my way through relaxed family business as I climbed toward David’s study. Once I’d even met up with Rachel hoovering the carpet, hardly the household duty an American might have expected from the wife of an English lord.

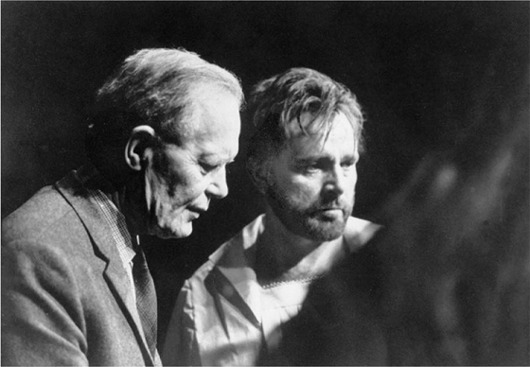

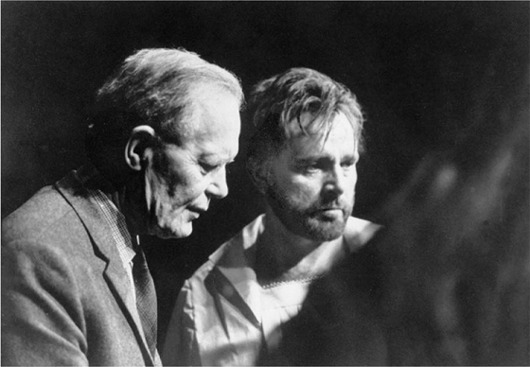

Nevill Coghill’s imposing profile is on the left. He was one of two unfailing pillars-to-lean-on during my Oxford years. The man on the right is Richard Burton, the powerful and celebrated actor whom Nevill virtually discovered in 1944 when he was casting a student production of Measure for Measure; and Burton (then at Oxford for a few months on a military course) turned up to read for whatever role might be possible. Nevill told me, years later, that he’d very nearly cast the role of Angelo with another undergraduate before he heard the eighteen-year-old Burton read. That plangent Welsh voice proceeding from that impressive pockmarked face was at once irresistible, and Nevill changed his mind. Burton never forgot the chance he was given—the first of many of the great Shakespearean roles—and he honored Nevill, affectionately, on numerous occasions. In fact when I spent a day with Burton in Rome in 1962, he told me at length about the detailed advice he’d got from Nevill in advance of a Broadway production of Hamlet, under Gielgud’s direction, two years later. I saw the performance and thought it unvaried in ferocity.

This picture was taken, by Terence Spencer, on the most notable occasion of Nevill’s work with Burton—in 1966 when Burton returned to Oxford to join Nevill in a co-directed production of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (with Elizabeth Taylor, Burton’s second wife, in the silent role of Helen of Troy). Following a successful run of performances in Oxford, virtually the entire university cast decamped to Rome and filmed the production in 1967. At the time of the film, Nevill was sixty-nine. I hadn’t then seen him for four years and never would again, though we corresponded faithfully till forgetfulness overtook my loyal friend.

The notion of an eventual D.Phil. under David’s supervision was still alive in my head, and he and I discussed again the possibilities of my returning in the not too distant future to complete that task. Then he took a long pause and urged me “not to court extreme loneliness”—I think I remember his phrase exactly. I thanked him and said I’d do my very best. As I stood to leave, David also rose and seemed on the verge of a parting embrace; but a spell of nervous blinking overtook him. He reached to his table and handed me a signed copy of his book of essays on Victorian novelists, apologizing for “a slender old book” which is nonetheless perhaps the best of his critical volumes. His now seldom-mentioned essay on Wuthering Heights, a book that he thought far and away the greatest English novel, goes deeper than any other known to me. At the time his lordship was fifty-six; my father had lived two years less. Considering how generous-hearted David had been in all our dealings, and given his apparent frailty, I thought for a moment we were parting forever; and I almost offered the embrace he declined. But not in England, not in 1958.

That same afternoon my farewell meeting with Nevill was more relaxed. In the past year he’d been voted into the Merton chair in English literature, then one of the few professorial chairs in English studies at Oxford. F. P. Wilson, his predecessor in the chair, had won it over C. S. Lewis; and Lewis had decamped for Cambridge. Nevill had won it over Helen Gardner. To a few, Nevill’s elevation seemed based on slender scholarly credentials. Miss Gardner was especially bitter at having been passed over, as she showed me in one of our last meetings. I was sitting beside her, in her study, as she read through one of my thesis chapters. In it, I referred to Nevill as Professor Coghill, though his inaugural lecture was a few weeks away. With her pencil she firmly struck through the word Professor and darkly muttered “Not yet.” Whatever her qualifications, she must have known that her great defect for the Merton chair was her gender.

The new post permitted Nevill to move, from his modest rooms in Exeter, several hundred yards across the High to Fellows Quad in Merton, the largest and most elegant of our quads. There he’d decorated his two-story suite of rooms in what one of his Merton faculty fellows described to me as “pansy modern.” To be sure, the décor was a little elaborate in spots; but I never reported the pansy opinion to Nevill, and he and I laughed over more sherry at my account of the recent disastrous state of Wystan Auden’s rooms. It was then that he told me a story from Auden’s student days. When Nevill had taught him some thirty years ago, he once returned to his study at Exeter to find the prematurely arrived Wystan rummaging through the papers on Nevill’s desk. The older man chided the younger on such behavior, but the adolescent Auden merely said “How do you suppose I’m to become a poet if I don’t know how people conduct themselves on paper?”

In late afternoon when I felt the need to move on, I asked Nevill for some wisdom to take home with me. All the years later, it seems a quaint request; yet he took it seriously and paused for an appropriate answer (despite his heretical sexuality he’d been described accurately by C. S. Lewis in their student days as “a Christian and thoroughgoing supernaturalist”). His answer for me was a story. Years earlier he’d been summoned to his mother’s deathbed. Lady Coghill had chosen an inconvenient time to die since Nevill was, I believe, serving as a Schools examiner—whatever, he had urgent duties in Oxford. He hired a small airplane to fly him from a tiny field in Oxfordshire to the family estate in rural Ireland; but when he arrived, his mother was in a final deep sleep or coma. He waited with his other muted kin as long as he possibly could before having to return to his professional duties; then he went in to kiss her sleeping head goodbye. She showed no response and he turned to leave quietly. As he touched the latch of her door, though, there came the sudden sound of her voice—“Nevill.” He turned to see her behind him, half-risen in bed. She lifted a frail hand and pointed toward him strongly. “Nevill, remember—I only regret my economies.”

As he finished his story in the dimming room, I could see that his bright eyes had filled. I stood to leave, knowing that I’d heard a crucial sentence—wisdom indeed, from a dying woman, brought forward by her son who was way past old enough to be my father. Few things I’ve heard have ever been wiser or of greater use in my own long life; and I pass the story on, every chance I get, to my younger friends and students—the story and the words it embodies (with a pronoun change): You’ll only regret your economies.

Nevill stood also, taller than I—not the first reminder I’d had of his time in the trenches of World War I where tallness was a danger—and folded me in. He was pushing sixty, he had a grown daughter somewhere far off, his marriage had ended decades ago, and I’d recently met what he called the great love of his life (a married man with children). Yet for all his cheer and competence and his legions of friends, Nevill had always seemed to me a lonely man. Still I knew he’d heeded his mother’s last words. He’d lavishly poured out his own deep mental and spiritual gifts; and however depleted the well must have seemed at many times, it had always refilled—as it had in all his unfailingly generous dealings with me. Another piece of parting wisdom then, to set by Auden’s characteristically peculiar observation, while I continued the complex labor of shutting the lid on three years of vital importance in my life.

* * *

In the few days left, I visited Stephen in London and spent two nights on Loudoun Road. One night we had dinner with his only surviving younger brother, Humphrey, who is only now being celebrated as the extraordinary photographer he’d been in his early years. I took to Humphrey right away, over dinner and through a long bibulous evening; but Stephen had never once mentioned his brother’s photography to me, and we didn’t discuss it that evening. Later I was often reminded how little Stephen’s surviving siblings—Humphrey and their sister Caroline whom I never met—figured in his present life, though he’d written (in the Forties) some of his finest poems about the last illness and death of Humphrey’s first wife Margaret. Enduring family devotion (apart from his immediate family) had got essentially omitted from his childhood skills, owing maybe to the early death of his mother and, thereafter, to his father’s lack of involvement with the children—all of whom were reared by a pair of exemplary hired sisters. (Surprisingly, after our dinner, I was sitting on the floor near Humphrey’s chair; and whenever Stephen left the room to pee—which was always often—Humphrey would lean forward and massage my neck or scratch my head. It was only in his obituary in the London Independent that I learned that he always told his three successive wives of his bisexuality).

From that visit to London I drove my Beetle on to Manchester for shipment to the States; and it seemed I’d make that long trip alone, despite the fact that the headwaiter at the Bombay Restaurant on Walton Street had asked to come along with me, just for the trip. He was a virtual twin to one of my childhood heroes, the film actor Sabu (the headwaiter’s name was Shamsul, and he was about my age). I’d never seen him outside the Bombay, though he’d kindly given me more free dinners in my recent near-bankrupt weeks. Maybe I feared beginning another intensity too late in my English stay, despite this young man’s small-bodied physical perfection. I also felt a certain familiar human need to deepen my own sadness at parting from the scene of so much learning, so much education in the most useful senses.

The nearest feasible port to my home in North Carolina was Charleston, South Carolina; and when I left the Beetle in the clamorous freight yard of a Manchester shipper recommended by my Oxford travel service, I more than half expected never to see it again. Nonetheless it had made my time in Britain—and through the continental summer with Michael—far richer than either might otherwise have been. I spent one solitary night in an enormous Manchester hotel, also commended by my ever-resourceful travel service. And by the time of my next-morning train back to Oxford, I’d indeed intensified my tangled compound of sadness and withdrawal. I’d also stirred into the mix a bracing awareness that, if I were ever going to become the professional fiction writer I’d told the world I was on the verge of becoming, then a return to home-ground central (northeast North Carolina) was my surest means of taking an even more serious step on into that venture. All I needed now—I told myself—was a safe voyage westward and the quick location of a quiet country house.

* * *

Back on Sandfield Road, I spent a last three days repacking my trunk with semi-lunatic care. When I’d wedged in (with elaborate jigsaw-puzzle assembly) every acquisition from a manically acquisitive three years—every new book, framed picture, sweater, all the other clothes, souvenir tickets, and theatre programs, all the saved letters from valuable friends, and on and on—then I called British Railways to come and collect it for shipment to dockside Southampton and the French line, bound for New York. (I’d sold dozens of books to Blackwell’s, including my near-complete Columbia set of Milton, in order to purchase a few pictures that were still available at startlingly low prices. I’d seen Kenneth Clark, for instance, a few weeks earlier on TV; and he said that original Rembrandt etchings, printed during the artist’s lifetime, could still be bought for “less than the television set on which you’re watching this program”; so even with a beautiful Craxton portrait of a young Greek soldier, I thought I had a lighter load than I’d brought with me three years ago.)

In response to my call then, two strong-armed men came to my study, took one look at the trunk, gave a hasty pull at the leather handles, and said “No way, mate. If we can’t lift it, we don’t have to take it.”

In considerable shock I said “What do you suggest then?” The larger of the men said “Saw the bloody thing in ’alf,” and then they were gone. So much for the reliability of a nationalized railroad (it was the most substantial rudeness I’d yet experienced in Britain; the customs men in Harwich were after all responding to an error I’d made). A little desperate, I bussed myself into town and asked my travel agent for help. He at once suggested a local private trucking company whose polite but suspiciously undersized men came, took one slow look at my trunk, said nothing to one another nor to me but (without further ado) proceeded to heave the deadweight burden onto their lorry and bear it briskly away—nearly seven hundred pounds as I’d learn to my amazement when paying the freight bill later that afternoon.

* * *

Oddly I don’t recall my last night in Oxford. Did I dine with a friend (almost all undergraduates had left for the Long Vac)? Did I eat a farewell complimentary curry with my Indian waiter friends at the Bombay (that would have required a bus transfer)? Did I drop in at St. Hilda’s and see if Miss Gardner was available for something (about as likely as calling on old Queen Mary herself with a similar proposal, though a few weeks earlier I’d taken Miss Gardner out to dinner and brought her back to Sandfield Road for a convivial last glass of wine and a good deal of talk)? Or did I simply stay in Headington, eat bread and cheese, make the odd joke with Win as she looked in at intervals, apparently abashed to show any feeling invested in my departure, and make my final preparations for tomorrow’s train to Southampton and the better part of a week at sea—if we made it safely? An Italian liner, the Andrea Doria, had after all sunk almost exactly two years ago with the loss of some fifty souls.

In the absence of any specific memory, it seems right to recall my final dinner with Stephen. He’d come to Oxford some two weeks earlier, and we’d met—for dinner maybe or at least a good talk. We realized clearly that a first round of our friendship was ending. Again we both knew—silently—that despite the difference in our ages, I’d been promoted to a new rank when Stephen consulted me about his domestic options in the crisis he precipitated during his concern for Osamu. The immediate change in our relation was that I’d no longer be within easy reach of London; but while it eliminated our chances of meeting often for theatre and music, that was surely no great problem. Given Stephen’s restless circling of the globe, we were bound to meet again soon.

And there were always letters. In those last good days before the telephone largely consumed the art of letter writing, we’d go on with our regular correspondence. Stephen had told me more than once how he felt that the best of him was contained in his journals and his letters; and now—twelve years after his death—there must be thousands of his letters that survive and remain to be collected and published. His brilliant biographer John Sutherland has written that “The largest private collection of Stephen Spender’s correspondence and literary papers is held by his friend of many years, Reynolds Price. It is deposited (under restriction) at Duke University Library.” They’re letters which—for intelligence, wit, and emotional and narrative coherence—equal any I’ve read since Virginia Woolf’s. He himself almost never kept copies, saying that he liked to cast his bread on the waters and leave it at that. There are more than three hundred in my files alone.

The deepest-cut memory from that late Oxford meeting was Stephen’s saying how he worried about the very thing that gave me most hope—the fact that I was returning to my old home ground (at Duke I’d be little more than an hour from my birthplace). His own intensely cosmopolite view—plus his lack of any real knowledge of the realities of life in my old world and, even more crucially, his lack of any strong ties to a parental family of blood kin—was that I might now proceed to write only about a few past realities, abandoning the new lines I’d pursued as my angles of vision expanded in England.

Mightn’t I eventually dry up (he feared a certain Medusa power at the heart of American culture)? Without ever having told his two oldest friends apparently, he felt that America had, to a large extent, sterilized the early gifts of both Auden and Isherwood. I didn’t mention that they’d exiled themselves from fertile home ground, whereas I was returning from temporary absence; and of course I didn’t point out—and never would—the clearly painful fact that his own poetry had virtually ceased.

What he was telling me was something he’d plainly thought a good deal about; and coming from such a canny and benevolent friend (one capable of an unpretentious wisdom that often ran in tandem with his personal confusions and defeats), his question lodged in my mind at once as a warning worth perpetual attention. Since I had no guarantee to offer him that I wouldn’t likewise succumb to some nameless cauterizing American plague, I could only assure him of an ongoing awareness. Wouldn’t a three-year immersion in a culture as profoundly different as the Britain of those years have insured me, for life, against the pointless provincialism that Stephen seemed to dread? Young as I was, I felt he was wrong; and I was young enough to say so. It was one more of my brash replies which he absorbed into the wide and silent blue-eyed German-Jewish gaze with which he filed away refusals that he fully expected to meet again when the person whom he’d warned eventually realized his rightness.

Well, I came from sanguine stock. Both my parents had owned very little to bank on but persistent hope; and here now I sat, their healthy elder son, all but straining at the bit with the goodness of my already-annotated plans for a longish fiction. I’d even recently acquired a title. A few months ago I’d gone to an Oxford showing of The Bridge on the River Kwai. I’d seen the powerful film, brand new, on the rolling Queen Mary with Alan Campbell; but on a second viewing, I heard more clearly one brief—and near final—speech of William Holden’s.

It comes near the film’s catastrophic ending, when Holden and his young accomplice are deploying their explosives. As they’re almost done, Holden turns to the young man; and here’s the note I made that evening, back in my study—

There is a line in Bridge on the River Kwai which might give a title for the Rosacoke story—“Let me wish you a long and happy life.”

I was too early in my writing career to realize how crucial titles would become for me, how they’d crystallize my central meaning and lure me onward. But here, more than eighteen months before I began really writing my story, I’d found its heart. Though I couldn’t yet know it, I was off and—was I running? I was moving onward in any case—and not only toward a story that would become a novel but toward a further life of my own, one as happy at least as what I’d yet lived through (despite the sadnesses to which I’ve alluded, I’d known a great deal of unmitigated joy).

With a sense of silent drama then, and the baggage of hope that was natural for me, this native son began his return to the bright orange clay and dense piney woods of his early life, the home of so much of his eventual work. On July 23, 1958 I faced back west and put to sea again in another old but agreeable French ship, the Ile de France—launched as long ago as 1927—entrusting myself, mind and body, for five more days to the all but bottomless surging breast of the North Atlantic.