4

MY MEMORY OF those working years at home is far less detailed—oddly maybe—than what I’ve recorded of my three years at Oxford. And I wonder why. The only answer I can offer is that Duke, Durham, and Raleigh were (so far) offering me a considerably less complicated world than I’d known abroad, a world marked chiefly by the writing, the teaching, the few pleasant evenings with colleagues, and occasional drives to Washington. Also when it came to travel, I was all but stone-broke still. My take-home pay each month came to some $300 ($2,100 now). From that sum I began to repay money I’d borrowed from a sympathetic bank manager during my Christmas visit home in ’57. Each month I repaid my mother $50 (some $350 now) for her many generosities, and my rent was $45 ($315 now).

Those payments left me with $200 ($1,400 now) for all my other needs and desires—food, rent, heating oil, clothes, a few movies and concerts, gas, and a few dollars saved for an eventual return to Oxford: I was trusting to return at the end of my three-year contract at Duke. Beyond the monthly checks from the university, I had no other income that I can recall, apart from two small checks from Encounter—all the more reason then to hunker in the woods and write. Among the few exceptions are the Washington weekends, a single trip to New York in the summer of ’60, and a ride with Michael to Princeton to attend Peter Heap’s first marriage.

Nonetheless I was far from unhappy. The years in Britain had left me well stocked with memories I continued to process. The final involvement with Matyas had not so much ended, for me at least, as sat merely suspended on what I’d heard as a rising tone—a chord that awaited resolution. Again, no one I knew could afford to telephone England with any regularity. There was no e-mail of course, so letters were the means of communication, and Matyas had the loyal British habit of prompt mail response.

It normally took five days for an airmail letter to cross the Atlantic in either direction. If Matyas got word from me on a Thursday, he was likely to post a reply within forty-eight hours (despite his own heavy teaching load). However welcome Matyas’s responses, I was often a little flummoxed at their speed. Still I labored to keep up my end of the correspondence, however placid my news might be in contrast to his. He sent me interesting accounts of his summer return to Eastern Europe and reunions with his family after a nearly fifteen-year hiatus; then regular and lively accounts of his ongoing Oxford life and work. But eventually he wrote—and mailed—a long and unnerving letter of blame.

* * *

He didn’t cast me as his primary villain—he saw himself as that—yet he certainly saw me as an enthusiastic instigator of a revival, in himself, of queer emotion and practice. In Oxford he’d told me of his fervently Catholic youth, and I knew that his queer energies had brought him essentially no happiness. I thought I’d witnessed a significant amount of proof, however, that our few months together had begun to heal his dread. Once we’d made an initial commitment to intimacy, he’d shown me only generous-hearted affection and a delight in our lovemaking that matched my own (not an easy match). But this bad letter indicated his prior concealment of deep reservations and bitter regret. It certainly suggested that any hope, on my part, of returning to Oxford for a long-term resumption of our affair was gravely misguided. That was hard news to get—and childish, I felt, from a man who by then was near thirty-five. In later letters, however, we each worked to repair his anger and restore at least a postal friendship that was all the stronger for having begun in mutual desire.

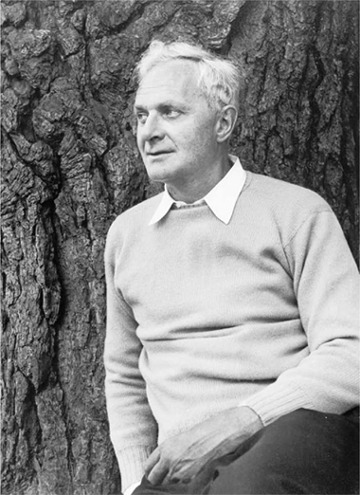

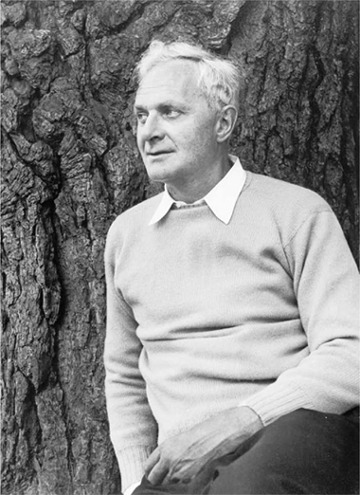

Stephen Spender, in California in 1959. Taken by the pioneer American photographer Imogen Cunningham somewhere in the Bay Area while Stephen was teaching at Berkeley, it captures his face better than any other portrait I’ve seen. He’s in the vicinity of fifty years old, with nearly four more decades to go, and is obsessively at work on a book-length poem about his life. His recent poetry has been severely attacked, and he’s hoping to rout his critics with something both new and legitimately strange. Whenever he’d visit me in North Carolina in my trailer or eventual house, he tended to sit up, working on the long poem, well after I’d retired to sleep. Now and then he’d let me see a few pages, always in his legible hand; and I always felt he was on a rewarding track, though one that he revised endlessly. He published one or two brief excerpts in literary magazines, but eventually he either abandoned the large project or set it aside for eventual completion. Then he died. If asked for my opinion, I’d urge the keepers of his estate to find a first-class editor and publish the entire poem, if it survives at all, just as he left it. Surely he wrote no better verse.

* * *

As for any romance, with sexual union, back home—there was none, barring a very occasional one-night stand with friends. In addition to chaste friendships with my teaching colleagues, I had several visitors from England. The stringent pressures on travel money for British subjects were still in force, and any Briton who managed to reach the States was in need of all the hospitality he could find. In my small quarters I welcomed several Merton friends and Julian Mitchell, whom I noted above—an eventual novelist, playwright, and screenwriter. All these friends were making their first trips to the States as they passed my way, and I mostly enjoyed giving them a brief version of the classic tour of upper Dixie—a drive down to exotic Charleston and Savannah or up to Richmond and Warren County with its village world of tobacco, its sixty-five percent black population, and my undaunted and loquaciously amusing aunts with their superb fried chicken, endless fresh vegetables, biscuits, cornbread, and blackberry cobbler. I even moved into the Mays’ house for a few nights and surrendered my trailer bed to John Roberts, my senior Merton friend, and his new (first) wife.

The visits became a little onerous as my writing proceeded, especially since the friends almost always arrived without cars of their own and were dependent on me for local transportation; but I don’t recall ever turning one traveler away (Michael was a regular and always welcome guest). Eventually I became bold enough to give most of them breakfast and then a walking stick with directions for exploring the woods and fields on all sides of my desk. I’d also provide semi-knowing instructions on the warding-off of bothersome snakes—the very poisonous copperhead was far from scarce nearby. The likelihood of such surprises was in fact slim; but my visitors seemed to enjoy even the barest possibility of cornering a poisonous snake, given that fact that Britain harbored only a single such creature, the adder which rarely bites a human.

* * *

As he’d promised, Stephen Spender often swung through Durham on his frequent lecture tours round America. He plainly relished staying in a caravan (the British word for “trailer”). With his love of country quiet and near-solitude, he’d happily absent himself during my writing hours and patrol the woods or set a chair on the hill above the pond and draw the landscape with my colored chalks or read or continue work on the long autobiographical poem which obsessed him for more than twenty years but which, with the exception of only a few impressive excerpts in magazines, he never published. In the evening we’d cook simple meals for one another on my narrow stove, and he’d unreel the often absurd news from his travels.

There’d be full accounts of the inevitable New York visits with Wystan Auden who was rapidly entering the airless tunnel of demanding eccentricity and hard drink that would make his last decades, however hardworking, so merciless on himself and his friends. And he’d have dined with the mentally unsteady but (to Stephen) always kindly and amusing Robert Lowell, not to mention the numerous lectures at small-college English departments of an often mind-boggling naïveté; and more interesting longer stints at Northwestern, say, or the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He’d even repeat, with laughing approval, Mary McCarthy’s remark after attending one of his lectures—“Stephen, that was hopelessly above the heads of three-fourths of your audience and hopelessly beneath the heads of the other fourth”: he relished telling such jokes on himself.

Clearly Stephen had a real sense of relieving my own country silence with these dispatches from the Real World; and at first I never tried to stem his flow—the stories were mostly interesting, sometimes even credibly scandalous. But in the later years of our still-frequent American times together, the boredom of Stephen’s endless touring round the lecture circuit led him to ceaseless complaints that were finally tiresome to hear, however aware I was of his need to support a London household. The very core of his final travels, and university residences, was boredom; and the word itself—boring—became boring to hear from a man who’d exhausted his own profound and enriching early curiosity about most things American. Nonetheless I had dozens of reasons to thank Stephen, and those thanks multiplied right on till his death some four decades after I left England (only the deaths of my parents struck a comparable deep mourning in me).

One of his kindnesses lay in directing me to an extraordinary sophomore student. In the spring of ’59, Stephen and I had gone to a reception in the Rare Book Room of the university library; and there in the small crowd I saw Stephen off in a corner, talking intently with—and towering over—a considerably shorter young man who wore thick mad-scientist glasses. Eventually I went over and met Stephen’s discovery. He was Wallace Kaufman, an English major who said, at once, that yes, he wrote poems. Initially he seemed suspicious of everything going on around him in this handsomely paneled replication of an eighteenth-century gentleman’s library, but he told me of his origins on the north shore of Long Island and of his coming to Duke on a combination of scholarships that made his presence possible.

He left no striking impression, then and there; yet as I drove with Stephen back to the trailer, he lapsed into a silence and then said, in effect, “That young man is the only truly proletarian American I’ve ever met.” I’d not had Stephen’s background in such older European class distinctions, so I said “How so?” Stephen said only “Christopher Isherwood would walk across the continent to meet him.” Then he laughed. “No, truly. I think you should get to know him. He said he was called Wally, and he seems a true original.”

And so Wallace Kaufman turned out to be. I didn’t begin to know him till the next academic year, by which time he was a junior. I’ve noted that he’d then be a member of that group of advanced writing students I met at the Chappells’ apartment. And there, almost at once, Wally’s rough-edged wit, his initial truculence (which dissolved when his dread of fake sophistication dissolved); and the talent on show in his poems and short stories made him the most interesting of my younger male students—one of the few who, given the nature of student-teacher relations, has proved a lifelong friend.

* * *

As the teacher of all those students—so close to my own age—some of whom would soon become friends, I was faced with a complicating reality. I was expected to submit realistic grades on their work and to interact with them in useful ways that didn’t violate the never-articulated (in those more innocent days) but implicitly moral expectation of teachers. I didn’t have the all-but-impermeable armor of tenure around me, and my three-year nonrenewable contract led me to think I never would, not at Duke. But even we young instructors knew that, like tenured professors, any one of us could be forced to leave the university for an act of “moral turpitude” (I soon learned, through the grapevine, of a male teacher in another department who’d recently been asked to leave for inappropriate behavior with a male student; the teacher was of course married; and apparently the university—as seems to have been standard then—had eased the offender into what proved a lifelong job at a good college elsewhere in the state).

At our small gatherings of instructors, we’d often haul out the “turpitude” phrase and remind ourselves—with nervous laughter—that it surely referred, above all, to sexual intimacy with students. Yet we had more than one senior colleague whose present wife had been his student when they met—had their courtships been turpitude-free? And given our duty as instructors to meet weekly, and privately, with each of our freshmen, we often talked about this or that young woman who seemed clearly to be offering herself for grade improvement, if nothing more committed. There was never talk of a flirtatious male student in those days, though there were surely such young men—as there were several queer instructors.

I vividly recall my first such awkward moment in a conference. An eighteen-year-old female student took the latest assignment—a thousand-word narrative of an interesting experience that had lasted, in the real world, no longer than half an hour of clock time—and produced a thoroughly graphic description of a babysitting experience (a little incredibly, the baby was a just-pubescent boy). My student had written in the first person, and her narrative ended as the babysitter proceeded to undergo her sexual initiation at the hands of the babysat boy—or so her theme claimed; she also claimed it was baldly autobiographical. Remember that this was the late 1950s; Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover would become a legal publication in the States only in the early ’60s. But here was I in my cubicle.

A plump, bright, and likable girl was seated with her left elbow on my desk as I read her paper, marking occasional errors and questions as my nerves tightened.

What was I going to say when, at last, I had nothing else to do but look up and deliver my response to this better-than-competent piece of work which nonetheless seemed designed to excite the instructor? My memory of her face as I met her eyes at last is of unabashed readiness—What is this grown man bound to do next? The office door was shut—a mistake I’d never make again for a student visit in my entire career, unless the student specified that he or she had come with a confidential problem (in which case the door would be slightly ajar). I’d be lying if I didn’t say that, for an instant, I welcomed this eighteen-year-old’s degree of audacious trust in her teacher’s impulses, wherever they led. Well, God alone knows what I said those fifty years ago; but no turpitude of any sort ensued.

* * *

And while Wally Kaufman became my best younger friend through the remainder of his undergraduate years, and though my feelings for him were a complex mixture of concern for his lack of a family, respect for his work, and a normal response to his odd magnetism, our friendship grew without the hindrance of a realized intimacy. Wally has only recently shown me a forgotten letter which I wrote him in 1961. I said “I have felt for a long time that one of the things we share, mysteriously, is a deepening relation with our dead fathers.”

I was alluding to the fact that my own father had died seven years ago; Wally’s had been killed in a car wreck in ’57, and my feeling was as honest as it was strong. Young as he was, Wally’s work was dealing powerfully and eloquently with that death. His father had been a nonobservant Jew, employed as a machinist at Grumman Aircraft on Long Island, a man who’d had slim apparent interest in his three sons and a turbulent relation with the boys’ mother, a gentile of good English family, bedeviled most painfully by bouts of clinical depression that sometimes led to her hospitalization. Though I was only six years Wally’s senior, I felt some responsibility for the fact that he was fatherless—as I was. That realization worked eventually to establish between us a relation that had considerably more paternal-filial energy at work than either of us realized in the early years of our acquaintance.

For three years at Duke then, and later for a year at Oxford, we spent considerable time together. The writing of fiction and poetry, which we shared with one another—and especially the translation of poems from French and German which we worked on together (Wally knew German; I didn’t)—was a more important literary bond than I’ve shared with anyone since. A delight in movies and in laughter for its own sake were likewise strong; and from late in his time at Duke on through our time in England, we traveled together often. Most memorable was a trip we took in the summer of 1960.

* * *

I’ve noted a single trip to New York in my first three teaching years. I went north to visit Stephen for a week at the home of Muriel Gardiner Buttinger. Gardiner was a psychiatrist with whom Stephen had a love affair in Vienna in the 1930s. From a Chicago meatpacking family, and thus wealthy, Gardiner was studying psychiatry in Vienna and had invested a good deal of her money—and the risk of her life—in conveying threatened Jews out of Austria as Hitler loomed. It was the story of Gardiner’s career that Lillian Hellman notoriously refused to admit purloining for her own alleged memoir Pentimento, a story that became the successful film Julia with Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Fonda. Safely returned to the States with her husband Joseph Buttinger, who’d been chairman of the Austrian Socialist Party in exile, Muriel had built one of the last private homes in her uptown neighborhood—at 10 East 87th Street—and the house had become Stephen’s perennial lodging during his frequent visits to the northeast. In the summer of 1960 then, I was staying briefly with Stephen there, writing in my own quiet room while he went about his New York appointments.

Wally was spending the summer before his senior year in his old home ground—Sea Cliff, Long Island—where he had a single room in what he called a flophouse that bore the grander name of the Artists’ Colony. Toward the end of my visit, he came into town and joined me and Stephen for several days. It was a time marked by two memorable events. The most striking occurred when Stephen cooked our breakfast and managed to attempt making coffee with a disconnected electric coffeepot that he set on a red-hot eye of the stove. Before Wally or I could rescue the pot, it was promptly ruined, with an accompanying stench of molten Bakelite, a not uncommon Spender debacle. A group debacle occurred that Sunday afternoon when we went with Stephen to call on his London friend the actress Irene Worth.

She’d appeared in Britain, very successfully, in Stephen’s translation of Schiller’s Mary Stuart and was now appearing on Broadway in Hellman’s new play, Toys in the Attic. She was occupying the handsome apartment of an absent friend, and we had drinks there before going down the block to a restaurant she’d found—a likable unelaborated place. More drinks, then a good deal of lively talk, a good deal of wine with the food. Then somehow Stephen led us far downtown to the apartment—or was it a house?—of a family, one of whom was the brother (or sister) of the very ponderable sculptor Louise Nevelson. By then I, at the very least, was cheerfully sozzled; and the other three in our party were tottering but talkative. Still, I thought a sufficient sobriety prevailed. We discussed the several Nevelson sculptures in the downstairs rooms and her numerous framed drawings; then Wally and I went upstairs with a young daughter and a girlfriend of hers—a thoroughly innocent talk in a bedroom, for maybe half an hour. Then the three of us men—Stephen, Wally, and I—took Irene back to her lodgings: long hugs and kisses all round.

I’ve mentioned thinking we were sober enough in our call on the family of Nevelson’s sibling. But twenty years passed and I went to a party for Nevelson in Durham—she was visiting one of the local institutions. She was eighty but energetic. I relished her famous false eyelashes, long and dense as black fur rugs; and once I’d mentioned my love of her work, I told her that Stephen Spender had taken me and two others to visit her sibling in 1960. Nevelson took a moment to search my face, then raised her laughing voice, pointed, and told me “You? It was you? They talk about it still—a precious memory!” Then she lowered her voice—“But weren’t you all drunk?” When I told her “More or less,” her voice rose again—“More, my boy, more!” The fact that—on my way to the Nevelson party (alone on my pitch-dark country road)—I had my single lifetime encounter with one immense strange aircraft very near overhead, seems barely strange at all: a hardly deniable UFO as I drove toward Louise Nevelson who’d kept, through her old age, a secondhand memory of me at hardly-my-best in New York long ago but laughing all the same. It felt immensely likely.

An hour or so after Stephen melted Muriel Gardiner’s coffeepot, he and Wally and I set off in Wally’s 1950 Ford to deliver Stephen to his planned visit with Edmund Wilson. The great critic was staying at his mother’s old home, upstate, in the country near Talcottville. It was a long bright day, and we reached Wilson’s unpretentious stone house late in the afternoon and went in for a drink and an hour of talk before Wally and I left Stephen there and set off on our own. My chief memories of Wilson include almost nothing he said, beyond a certain almost oblivious kindness to us two young men. I do, though, clearly remember his physical smallness, plumpness, and pallor and the fact that he barely moved from a tall upholstered chair in which, he told us, he often spent whole days and nights—reading. He’d nap upright, then wake to read more until eventually his housekeeper would suggest a wash and a change of clothes (he was then engaged in the reading for his most distinguished book, a study of the literature of the Civil War, called Patriotic Gore). He also said that Elena, his fourth wife, spent the summers elsewhere and that he was tended by a local woman who came in for a little cleaning and minimal cooking. At the time, Wilson had just turned sixty-five; but for me he had the almost transparent physical air of an ancient Chinese sage with tiny expressive hands and a tendency to talk straight forward to the air as though none of us was present.

Before dark we left Stephen there and forged off on our own. Wally had long since been a book scout, one who haunted secondhand bookshops, junk shops, Salvation Army stores—anywhere he might find a book of interest to himself or to some other scout or dealer—and we spent the next few days in upstate New York, wandering through such places. I’m not sure what Wally found; I only recall that one shopkeeper ordered us to leave his premises when Wally wouldn’t say precisely what he was hunting. Maybe Wally looked too knowledgeable in his thick glasses; we might find some treasure the dealer was unaware of—only lately I’d read of some grubby lad who’d just found a first edition of Walden in a junk shop and bought it for fifty cents.

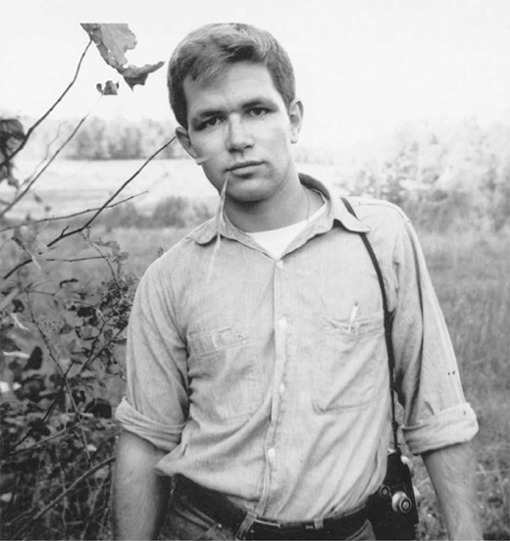

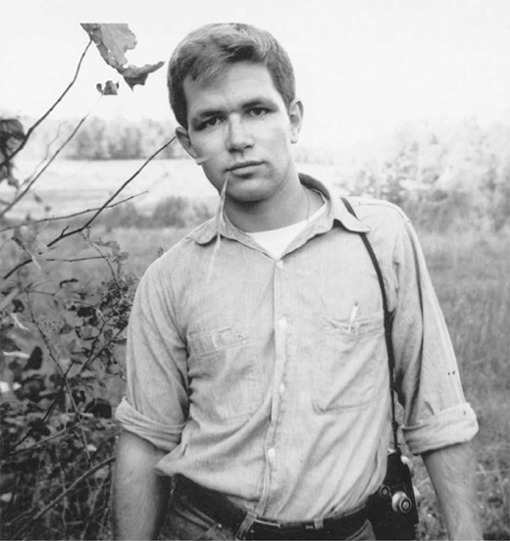

Wallace Kaufman was one of the first students I taught after returning from Oxford in ’58. A native of New York, he came to Duke on a generous scholarship a year before my return; and his interest in reading—especially poetry—and in writing both poetry and prose caught my interest early on, as did his extraordinary looks: a big-boned, powerfully shaped skull and large unblinking eyes. He was a member of the most rewarding class of writers I ever taught. The Marshall Scholarship took him from Duke to my old college, Merton; and his first year there coincided with my fourth year back in the college. We availed ourselves of joint trips to the entertainments of London; and we shared many friends—including an evening with the ghoulish great painter Francis Bacon. Though later life propelled Wally to the woods of Oregon, we’ve never lost touch. Here in 1961 he’s near the small pond beside which I’ve lived for more than fifty years.

In fact not long after Wally returned to Durham in September for his senior year, he phoned me one morning to ask if I’d ever heard of a book called The Grave with designs by William Blake, engraved by Schiavonetti. Blake was one of my minor interests (not long before, Stephen had given me a pair of the original Blake illustrations for the Book of Job), and I said I’d indeed heard of the book. Wally said “Well, there’s a copy of the first edition downtown at the Book Exchange for five hundred dollars.” I didn’t have five hundred dollars to spare, but I was devoted to not regretting my economies, and I said I’d meet him back at the store in half an hour. When we met, Wally led me through the spooky corridors of that famed emporium and pointed out the volume.

The book was in excellent shape; and I leafed through the numerous handsome engravings, based on striking watercolors by Blake and, though not among his great achievements, a handsome collection in any case. Then I looked to the inside front cover where the price was penciled in. There was a dollar sign, the numeral five, then two smaller zeroes with a slight line beneath them. I turned to my friend and said “This book costs five dollars, not five hundred.” Wally could hardly believe me when I said “In which case, it’s yours; you found it.” He took another look at the numbers and said “I think you’re wrong.”

So I said “Then go to the cash register, take out a five-dollar bill, and extend it to the man” (a notorious curmudgeon). Again Wally shook his head but followed my suggestion. A few minutes later we were back on the street with a first edition of Blair’s The Grave with all Blake’s designs as engraved by Schiavonetti—for five dollars plus a few cents tax. And it says a good deal about Wally’s good nature that a year later, when he found a broken copy of The Grave in some other book midden, he gave me my choice of the engravings. I chose “The Soul hovering over the Body reluctantly parting with Life,” and I have it near me still.