7

THE SOLUTION to another very serious concern remains mysterious to me, and my files don’t offer a full explanation nor does my memory. I’ve mentioned, more than once, that I and my colleagues had been hired on three-year nonrenewable contracts. Yet at some point in our third year, Arlin Turner—our new chairman who was hard at work on his Hawthorne biography—let the instructors know that all eight or nine of us would be offered a fourth year to search out another job for ourselves when our Duke appointment ended. That dispensation, standard enough in academia, didn’t appear to affect me since I’d be in England for that extra year. So I went to Professor Turner to inquire as to whether I’d be given one more year’s employment on my return from England. I specified that I’d be spending that year in Oxford, hard at work on the D.Phil. which I’d already commenced.

Turner was a shy and secretive man but courteous. Once I’d explained myself, he looked across his desk at me slowly and then said “Why do you think you need a doctorate?”

It was a little as though God had said “Why do you think you’ll need oxygen from this moment onward?” I replied that I’d hoped, for more than ten years, to spend a great part of my life teaching in a university and that I assumed a doctorate was the indispensable union card for such an intent.

Turner thought for another long moment and then said “Reynolds, if you go on writing fiction of the quality you’ve produced in recent years; and if it goes on meeting with such critical welcome, I can’t see why a doctorate would be required for you to continue a teaching life at Duke.”

The newness of such a thought was again overwhelming; yet Turner was a highly respected member of the scholarly guild and chairman of a large department at what was then considered the prime university in the American South—one with increasingly warm ambitions to stand even higher in the list of American universities. So he plainly wasn’t lying.

We talked another few minutes (a ten-minute professional talk with Turner was a relative eternity). And by the time I was on the way back to my office, I was seeing how I could—that very day, if I chose—abandon my plans for an Oxford doctorate, though I’d go on planning to revisit my old rooms in Merton, reigniting a strong relation with Matyas while I wrote however many more stories I’d need to complete a volume—my second book. One way or another, I thought I had enough ideas to keep me busy; and I’d need to be occupied steadily enough to combat the Thames Valley blues.

A further encouragement lay in the fact that my friend Wally Kaufman had recently won a generous Marshall Fellowship for two years of study in Britain. He’d applied to Merton, been accepted, and should be arriving a few weeks after me for a B.Litt. thesis on Wordsworth. I’ve generally been a slow responder to titanic psychic events in my life, so the elation attendant on the actual discovery that I was now liberated from a doctoral degree only dawned on me over the weeks it took to get me back onto the surface of the North Atlantic.

* * *

My third year of courses—with all the last rounds of freshman themes, upper-class term papers, and final exams from them all—would end in early June 1961. I’d booked my passage to England long ago—the old Queen Mary again, sailing from New York on July 13—and had only some five weeks left for preparations. Given the uncertainty of my plans at the end of the forthcoming year, I felt I had no choice but to vacate my much-loved trailer beside its pond (Mr. May had never raised my original forty-five-dollar rent). So once again I turned to the packing—would I ever settle in a single place and live there forever?

I was lucky that Mother’s basement could easily absorb my dozen-odd cartons of books, records, pictures, and clothes. By early July then I’d slowly moved almost all my boxes to Raleigh; and not at all incidentally, I’d spent as much time as possible with her and Bill. By then my brother had just completed his sophomore year at Duke, and Mother was continuing her job in the boys’ clothing store. While her salary was still small for the hours she invested (always upright), the chance to see her old friends as they visited the store was patently good for her spirits, as she readily acknowledged. When I’d mention the hope that, should my novel succeed, I might be able to retire her, she’d always laugh and fend off the notion—“But son, what would I do with the time?” Well, I had no serious alternate life to offer anyone who savored independence, on however slim a budget, as intensely as Elizabeth Price.

After I’d accumulated more than four years of astonishingly reliable service from my Volkswagen Beetle, I was planning to leave it for Bill. When I was back I could either reclaim it or, money permitting, buy something new. Meanwhile I made several trips to Warren County for meetings with Aunt Ida in Macon and my three Price aunts in Warrenton. By then Ida was in her early seventies and was living alone since Uncle Marvin’s death. In the same Rodwell house in which she’d by now spent most of her life, she seemed as at-home as any deer in the woods; and the house itself was the world’s most welcoming to my heart and mind. I’d always sleep in the far bedroom, in the space and on the iron bed in which I’d been born twenty-eight years before.

After a modest supper Ida and I would sit in our accustomed swing on the front porch, and the evening would slowly darken around us in its indigo way. The apparently immortal whippoorwill would commence its maddeningly repetitive call across the road—maddening but indispensable. The house just behind us was quiet as the earth that would one day enfold it, with all its freight of love and tragedy—the deaths of both my maternal grandparents at early ages, of one of their children in infancy, the orphaned sadness of my mother’s girl-hood and who knew what other broken hearts among a houseload of children, my own hard birth, and Ida’s ten-year suicidal depression (she jumped from a rapidly moving car, took a hard head wound, but survived and very slowly recovered).

And as Ida answered my latest question about our history, I’d occasionally take my—for now—maybe final glances at her face. Was this our last meeting? Who or what or where might she be a year from now, assuming I returned to this spot in safety? In any case, here we affirmed our unquestioned devotion in words about others (all of them kinfolk), in chuckles that eventually silenced themselves while sleep advanced from beyond the oaks we could no longer see at the edge of the yard when darkness at last perfected itself.

* * *

On July 2, less than two weeks before my departure from Raleigh, the radio announced that Ernest Hemingway had just killed himself by gunshot in Ketchum, Idaho. He was only three weeks from the age of sixty-two and had been not only far the most famous writer of my lifetime but one whose work—since I began to read it in high school—had been of central importance to my own. A decade after his death, I’d write a long essay called “For Ernest Hemingway.” It was both an attempt to describe what was supreme in the work of a writer who, in the shadow of his death, had begun to be picked at by the sharks whom he’d long foreseen in The Old Man and the Sea and also an effort to understand his meaning to me, both my life and my work. After a visit to the handsome old house in Key West, which he’d abandoned after his second divorce, I realized that what had moved me most—from my early adolescence till now—was the often concealed voice of a badly wounded man. All Hemingway’s much-publicized swagger, at the edges of Spanish bullrings or in the midst of the world’s saloons, could not entirely conceal that pain and its outcry. And my early discovery of its presence in words—the words he’d taught so many other readers and writers to use as if it were the speech of our tribe—had strengthened me to know what language itself could do for a private pain.

Michael Bessie at Atheneum had told me, some weeks before Hemingway’s death, that he’d managed to get a copy of the proofs of A Long and Happy Life to the great man; perhaps he might read it and say a word to help us. I well understood that the likelihood was hardly existent. What man of my own generation, though, would not have been roused at the thought that a story of his own might have gone past the eyes of such a master—one who might just speak up? Is it too absurd to recall, here nearly fifty years later, that one of my first thoughts at the news of Hemingway’s awful death was the realization that, if my novel had ever reached him, it hadn’t saved his life? He’d valued good work after all, at whatever honest trade, more highly than anything else in his life—indeed in the world. Still, like so many other members of his immediate tormented family, he’d chosen to end the pain in violent refusal. His last wife Mary would later say that, for long months afterward, she’d picked bits of skull out of the wall behind his last shot.

* * *

On the grand old overnight Silver Meteor, on the Seaboard Air Line Railroad from Raleigh to the imperiled glories of Penn Station, I got myself to New York a few days before my sailing date; and after a good night’s sleep at the Taft, I had my first experience of what was then politely called (though never by Eudora Welty) the drunch with Diarmuid. Drunch of course meant “drunken lunch,” and so it was for me—Diarmuid maintained the self-possession of Achilles on the plains of Troy. We each drank three virtually pint-sized martinis, talked of my excellent luck so far, and said a good deal about our mutual friend Eudora. We were worried about her, pinned down at home by a mother who’d been ill now for at least five years (the woman whom Diarmuid and I didn’t know, but suspected of being a termagant, was nonetheless loved to the furthest point by Eudora). As I’ve said, Diarmuid was the son of the Irish mystic poet Æ, a lifelong intimate friend of Yeats and numerous others from the Celtic revival’s flowering of poetry and drama in the early years of the twentieth century. And with no air whatever of showing off, Diarmuid had good stories of the famous modern Celts. The great Lady Gregory for instance had given the young boy Diarmuid a gold watch for his birthday but concealed it on her person. It was up to the child to frisk her thoroughly and find the gift, which he did, though (as he told me) “There was rather a lot of Aunt Augusta to search.”

My favorite—and a chillier tale—was his story of approaching William Butler Yeats about Diarmuid’s father’s funeral. George Russell had died in England but been brought to Dublin for burial. Mrs. Russell simply said to my eventual agent “Diarmuid, step round to Willie’s and ask him to give the eulogy at your father’s funeral.” When Diarmuid got to Uncle Willie’s, the poet was still in bed, reading proof. Russell and Yeats had been friends since early manhood and were close companions in much of their work. So Diarmuid delivered his mother’s message; Yeats read another line of proof, looked up, and said “Oh Diarmuid, tell your mother I’m afraid I won’t have time to do meself justice.” Æ was buried then without words from Willie; and it was not long after that Diarmuid chose to come to the States for the rest of his life.

One of his many Irish stories—generally elicited by questions from me, who’d taught Yeats’s poems for the past three years—would be told with a kind of stony glee from Diarmuid, by then on his second or third martini (and I recount them here strictly from memory, with no earlier notes to support my confidence). Diarmuid’s tales of chicanery or foolery in contemporary publishing were offered with similar level-headed emotion, though God knows how. When his and Eudora’s correspondence was eventually published, it became clear that she’d been a writer-and-client of special (though noncommercial) value to him and the agency in its earliest days. But when he and I spoke of her through the drunches of the next long decade, his concern for Eudora and the fact that he felt she was overburdened at her mother’s querulous bedside was apparent; yet what he never showed in our conversations was any clear degree of affection for Eudora—or any other client.

Though thoroughly Irish, Diarmuid’s emotional reserve in conversation was unbroken. Perhaps it was merely reserve; perhaps he was incapable of displaying the sort of feeling that might have been expected of one who’d done Eudora, and others, such loyal service—Eudora’s gratitude and affection, for instance, was literally boundless; and she never entirely recovered from his death as she showed quite plainly in our own frequent talks so long as her memory could express itself (several years after his death, when I was well past forty, she suddenly rebuked me for not attending his funeral in Bedford, New York during Christmas week of 1973).

Despite their long closeness—and Eudora’s many visits to Diarmuid and Rosie Russell’s home near Katonah, New York (I accompanied her there for one happily uproarious overnight stay)—Diarmuid never visited Eudora in her home till well after he knew he was dying of lung cancer. Then he flew down with Rosie for a typically over-the-top Mississippi celebration of Eudora’s work. I was there too and quickly saw that he’d gone beyond any desire to converse. But my awareness of the care that Eudora took of his fragile state, in the midst of so much ballyhoo, was silently touching.

The sight of a much-reduced Diarmuid attending the social events of that weekend was more than poignant—the cancer had sculpted his hawk head to the literal bone, like an object washed for years by a harsh sea. It was still capable, though, of meeting my gaze across a crowded and twittering room of club ladies with a very slow and narrow-eyed but closed-lip smile. By then he’d after all guided my career for nearly twenty years with seamless wisdom and—rarest of all, then and now—a same-day-received response to all letters and a courteously fierce will to defend me at any time he felt my interests needed such attention. And through it all I never heard an impatient word from him; nor (once I’d accepted his assurance that A Long and Happy Life was truly a novel) did I have another moment’s resistance to his proffered, but never insisted upon, advice. Such literary agents were rare enough in his lifetime; now they are all but nonexistent.

* * *

On one of my few pre-embarkation afternoons, I went to meet Hiram Haydn at the first home of Atheneum in the ’30s on the East Side; and he took me up and down the central staircase of the small converted residence and introduced me to virtually the entire staff—from his two partners down through the copyediting, design, and publicity departments. They all seemed likable human beings, as they’d already proved to be in correspondence; and their loyalty would continue for years to come (Hiram fell out with his partners in only a few years; and on Diarmuid’s recommendation, I stayed at Atheneum when Hiram left for an unsatisfying stint at Harcourt Brace).

Later that afternoon Hiram, Harry Ford, and I walked to Grand Central where we boarded a train for Westport, Connecticut and were met at the station by Hiram’s wife Mary—I’d be spending the night.

Mary was younger than Hiram and was a fellow North Carolinian; in fact I’d known one of her sisters since my childhood. In their likable home I had a half-hour to wash up, meet their teenaged son Michael, then head downstairs for outdoor drinks before dinner. Almost none of my present friends drinks the way a great many of us did, quite casually, in the 1960s; and there on a green-edged patio, Mary and Hiram and Harry and I drank a good deal and laughed till past summer-dark before going in for excellent food.

It was then that I had the first chance to begin really knowing Harry Ford who’d already designed my novel so elegantly. A small-scaled man, fifty-two years old, he was given in those days to a large-scaled enjoyment of his usual surroundings (his wife had stayed in New York). And in the course of the evening, I learned that Harry and I shared even more interests than I did with Hiram—poetry, music, and laughter above all. After his death in 1999 at the age of eighty, a knowledgeable mutual friend told me that Harry was born a bastard child and never knew a father. I’m unable to guarantee the assertion (and the mutual friend—the poet Anthony Hecht—has subsequently died); but if true, it could explain a number of the increasing difficulties Harry displayed in dealing with several of his male novelists and poets, me included eventually.

Yet it would be Harry with whom I continued my publishing career for twenty-six years more, till a much-changed Atheneum requested his departure; and he returned to Knopf. With all the warmth and thanks I feel for Harry’s help—above all in our first twenty years when he and his second wife Kathleen, whom I really loved, would pay me an annual visit in Durham—I still have enduring gratitude for all that Hiram Haydn gave me and my work at the start. When I left him on Forty-second Street that July morning of ’61, back in New York, Hiram assured me that, during my absence in England, he’d move Heaven and Hell for Rosacoke and Wesley; and with his tall frame and his huge beetle-browed head, he very nearly did.

* * *

On the day before sailing, I went alone to the first American showing of Luchino Visconti’s masterpiece, the long film Rocco and His Brothers. It was not the first Visconti film I’d seen; but my own thoughts for the next long fiction were beginning to circle relentlessly round the idea of a multigenerational family novel, one which leaned on my own family’s history. And while Rocco concerned itself with the tragedies confronting a family who come from southern Italy to crowded Milan, the film’s complexities of love, loyalty, violence, and hate excited my ideas further (because they were so much like problems in my own extended family). It likewise introduced me to the work of a young actor—Alain Delon—who’d soon be the prime male star of Franco-Italian film. What was most surprising about Delon’s work in Rocco was the fact that, through nearly three hours, he managed to portray a young man who is not only (of all things) a serenely beautiful prizefighter but also a kind of secular saint—and a thoroughly credible one at that.

With such a bold and ultimately productive memory, I boarded the Queen Mary. Nearly all I remember from my third eastward crossing is the nearly unbearable heat of my cabin, buried deep as it was in the hold, for the first two days at sea—it took that long for the New York swelter to be flushed out by cooler ocean air—the old ship was not air-conditioned. Five days of shipboard life—which must have included talks in the lounge with at least a few others, surely the immense heavy English meals and frequent naps—have failed to register in my memory. I recall a farewell glance back toward the Statue of Liberty and a renewed love of the ocean itself (the half-asleep monster that barely tolerated our passage and whom I felt I might have spent my whole life risking as some form of professional sailor), then a landing five days later at nine in the morning on a pier in Southampton—July 18, 1961, almost three years exactly since I’d last seen England.

Since I’d have no further worries involving graduate work—and would have no car and very little money—I was looking forward to unhurried meetings with my old friends (mainly David, Nevill, Tony Nuttall, and Win Kirkby in Oxford; Stephen and John Craxton in London, Anne Jordan in Brighton, and whatever new friends I’d meet wherever). The theatres of Stratford, London, and Oxford would be nearby—plus the better restaurants when I had the cash. And since Merton had generously said I could live in college for the whole year, I’d hope to spend a great deal of time on the short stories I’d begun to plan, to round out the volume that would be my second book. I even had dim ideas for a second novel.

In very few weeks, I’d be getting the first sets of proof on A Long and Happy Life from New York and London—the elegant slender galley proofs that we got in those years and then the smaller corrected page proofs that gave a young writer the last rousing sense of writing his book almost from scratch, though massive corrections could cost him a packet. I was already hoping to enlist Tony Nuttall with proofreading help. He was married now, living in north Oxford, and starting work on his own D.Phil., supervised by Iris Murdoch after being refused by Helen Gardner.

With any luck, I’d hope to have the finished book in hand by early spring, some ten months before I was thirty years old. That hope, and the false expectation of frequent warm meetings with Matyas, were the strong cords that (through a bright day) literally drew my train on to Oxford, the only city in which I’d actually lived with all but unbroken pleasure for a bold stretch of years—and would do so again.

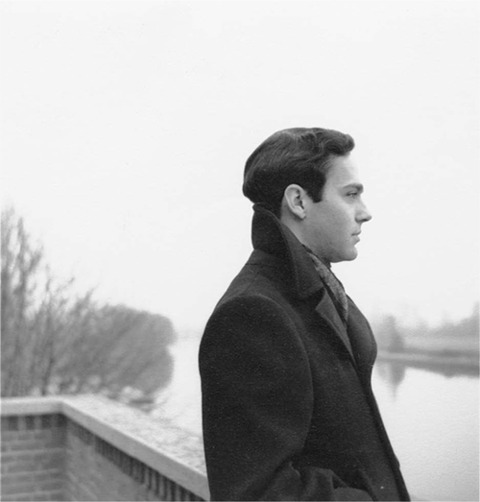

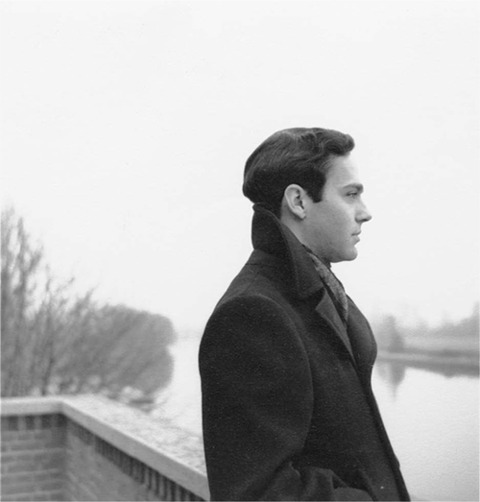

RP on the balcony of the Merton College boathouse, winter 1961, taken by Wallace Kaufman. I’m back in Oxford for a fourth year—a year that I thought would consist largely of writing a doctoral thesis or fiction of my own. The thesis proved unnecessary and was abandoned before I reached England, and very little fiction proved ready to be written so soon after my completion of A Long and Happy Life. I spent a good deal of time, then, with old friends like David Cecil, Nevill Coghill, Stephen Spender, and Tony Nuttall. My former student and friend Wally Kaufman was a student at Merton by then; and on one of our frequent walks round Christ Church Meadow—neither of us owned a car—Wally took this picture. The river is the Isis which ran past the Meadow, and I look unusually serious. Well, it’s plainly a gray day.