The successful employment of armoured cars in the reconnaissance role by both the British Army and German armies during the fighting in North Africa in 1940 and 1941 generated an interest within the US Army for similar vehicles. As a result, American industry was tasked in July 1941 with the design and development of a number of dedicated medium and heavy armoured cars.

It was the thickness of the armour on the vehicles that defined the difference between medium and heavy armoured cars, and not their weight. With that being said, the thicker the armour the heavier a vehicle would be. In July 1941, the plan called for the medium and heavy armoured cars selected for production to be suitable for employment by both the American and British armies. None would be ready for testing until 1942.

To answer the call for a medium armoured car, both the Ford Motor Company and the Chevrolet Division of the General Motors Corporation submitted vehicles for testing. The Ordnance Department had assumed responsibility for setting the requirements for all US Army wheeled and tracked vehicles, testing, design and their procurement in August 1941.

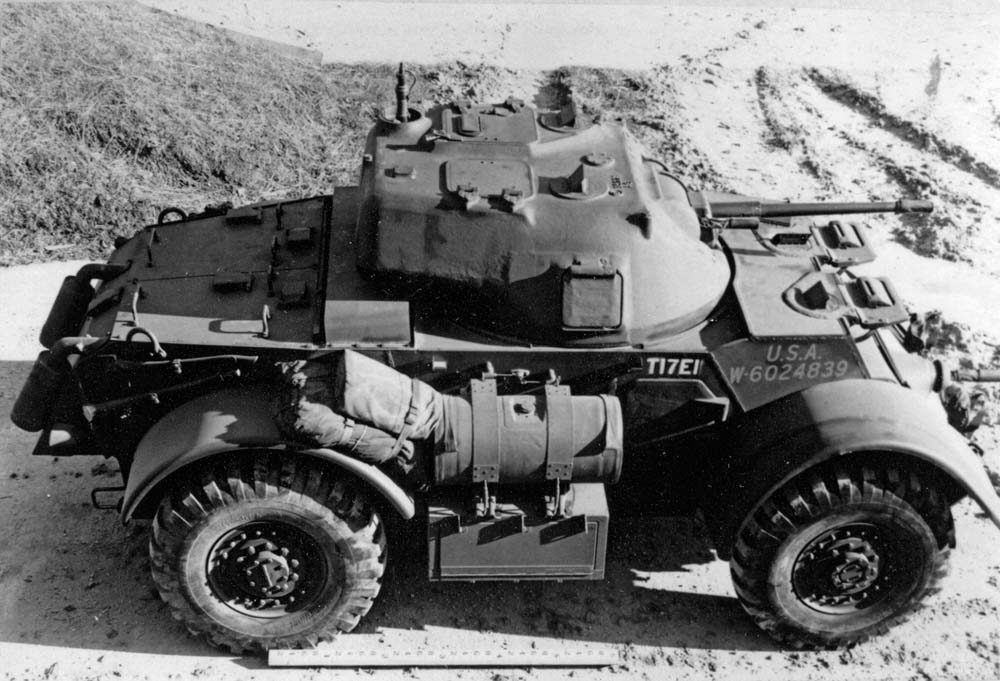

The Ford medium armoured car was labelled the T17 and was a 6 × 6. The General Motors vehicle referred to as the T17E1 Medium Armored Car was a 4 × 4. Both had the same 37mm main gun-armed turret designed by the Rock Island Arsenal. The 6 × 6 T17 prototypes impressed the US Army to such an extent that there was an order placed for 2,260 units of the vehicle in January 1942. A second order for an additional 1,500 units was authorized in June 1942.

To manage the large numbers of AFVs being considered for production, both wheeled and tracked, the Ordnance Department formed the Special Armored Vehicle Board in late 1942. One of its tasks was to determine the US Army’s requirement for armoured cars. Those not meeting certain requirements were to be cancelled to rationalize series production.

At the time that the Special Armored Vehicle Board was formed, the various members of the user community had different opinions on what type of armoured cars they wanted and how they would be employed. This difference of opinion was due to the mission diversity of the intended users, which included the Cavalry Branch of the US Army, and the US Army Armored Force and Tank Destroyer Force.

After evaluating the T17 Armored Car, the Special Armored Vehicle Board cancelled the orders for the vehicle. The Board believed that tracks were more suitable for vehicles with a gross weight exceeding 14,000lbs, due to their superior off-road performance. The T17 had a combat-loaded weight of 32,000lbs.

To help Ford keep the production lines going, the US Army Special Armored Vehicle Board authorized Ford to produce 250 units of the T17 for the British Army, who had already assigned it the name ‘Deerhound’. However, on reviewing the US Army’s test-data, the British Army rejected them, and thus none ever went overseas.

An unknown number of the T17 Medium Armored Cars (with their weapons removed) would be allocated to US Army Military Police units serving within the United States during the Second World War.

US Army testing of the smaller and lighter 4 × 4 General Motors prototype T17E1 went reasonably well, with some minor design issues being quickly corrected. At that point in time, the US Army was considering standardizing the T17E1 as the Medium Armored Car M6.

The T17E1 weighed 30,705lbs when combat loaded. Despite being a more reliable vehicle than the T17, the Special Armored Vehicle Board felt the T17E1 was also too large and heavy for a reconnaissance vehicle and cancelled it in December 1942. The British Army remained interested in the T17E1 and the Ordnance Department authorized General Motors to build the vehicle for them. The British Army assigned the name ‘Staghound’ to the T17E1.

The design and construction of two medium armoured cars fitted with an independent suspension system was authorized in January 1942. They were both built by the Chevrolet Division of General Motors and designated the T19 and the T19E1. Most previous American military armoured cars and scout cars had employed commercial truck suspension systems, fitted with leaf springs.

As could be expected, the off-road mobility of the T19 and T19E1 medium armoured cars was outstanding, with their independent suspension systems. The US Army recommended that future armoured cars be fitted with independent suspension systems. However, both greatly exceeded the weight limit set by the Special Armored Vehicle Board. Like all the other medium and heavy armoured cars submitted for consideration by the US Army, neither was approved.

As a test, a large turret armed with a 75mm main gun was mounted on the chassis of the Medium Armored Car T19E1 in November 1942. The combination was designated the T66 tank destroyer. There was British Army interest in the vehicle at first. However, like the T55 and T55E1, the Tank Destroyer Force quickly cancelled the T66 when it was clear that full-tracked tank destroyers had much better off-road mobility.

Besides the two different types of medium armoured cars submitted to the Ordnance Department for testing in 1942 by American industry, a heavy armoured car appeared. It was labelled the T18 and was an 8 × 8 vehicle. The builder was the Truck and Coach Division of General Motors, which began in-house testing of the first example in July 1942.

Originally intended to be fitted with the same 37mm main gun armed turret that went on the T17 and T17E1, British Army combat experience in early 1942 showed that the T18 would be under-gunned. This resulted in the second example of the vehicle being armed with a British-designed 57mm anti-tank gun and designated as the T18E2. The vehicle’s combat loaded weight was 53,000lbs.

As could be surmised, both the T18 and T18E2 were too large and heavy for the Special Armored Vehicle Board and were rejected for use by the US Army in December 1942. The British Army still saw a need for the T18E2 and at one point had envisioned ordering 2,500 units. As testing of the vehicle went forward and design problems became more evident, the British Army eventually reduced its order to only thirty units, which it named the ‘Boarhound’.

Even as General Motors was building the first example of the T18, armed with a 37mm main gun, it offered the US Army a 6 × 6 heavy armoured car. The proposed vehicle was designated the T18E1. The US Army was not interested and the project never got off the drawing board.

In early 1941, the US Army decided it needed a wheeled tank destroyer armed with a 37mm anti-tank gun as quickly as possible. The Chrysler Corporation responded by mounting an armoured-shield protected 37mm anti-tank gun in the rear cargo bay of an unarmoured 0.75-ton 4 × 4 truck. It was labelled the M6 Gun Motor Carriage (GMC). Hereafter, all GMCs will be referred to as ‘tank destroyers’.

Series production of the M6 tank destroyer began in April 1942, with Chrysler building 5,380 units of the vehicle by October 1942. It was intended strictly as an interim design, until a better thought out wheeled tank destroyer could be developed and fielded. Despite being a stop-gap design, the M6 would be deployed to North Africa beginning in November 1942, during Operation Torch.

An observer of the M6 in North Africa stated the following in a March 1943 US Army report: ‘The sending of such a patently inadequate [tank] destroyer into combat can be best termed a tragic mistake.’ In an After-Action Report (AAR) titled Operations of the 1st Armored in Tunisia, Major General E.N. Harmon stated: ‘The 37mm self-propelled gun, mounted on the 0.75-ton truck, is positively worthless and has never been used in this division.’

A number of experimental wheeled tank destroyers were also tested by the Ordnance Department but eventually rejected. There was the T14, an open-topped 6 × 6 armoured vehicle based on Jeep components armed with a 37mm anti-tank gun. Another was the T33, also armed with a shield-protected 37mm anti-tank gun, but mounted on an unarmoured 0.75-ton 4 × 4 Ford truck. It was later up-gunned with a shield-protected 57mm anti-tank gun and re-designated as the T44.

The need to mount an anti-tank gun of sufficient power to penetrate the armour on German medium tanks led to the US Army testing an open-topped armoured vehicle armed with a forward-firing 3-inch anti-tank gun. The 8 × 8 vehicle was designated the T55, with a modified second version being labelled the T55E1.

Both the T55 and T55E1 had been designed and built by the Cook Brothers Company, and hence were nicknamed ‘The Cook Interceptors’. Ordnance Department testing of new full-tracked tank destroyers quickly demonstrated that they possessed superior off-road mobility to large, wheeled tank destroyers, and the T55 and T55E1 were soon cancelled.

In July 1941, the US Army began searching for a replacement for the M6 tank destroyer. American industry was therefore asked to submit five candidate vehicles, for testing by the Ordnance Department, which had already laid out the general design parameters of the vehicle. All five candidate vehicles would be fitted with the same two-man turret armed with a 37mm main gun, then the primary anti-tank weapon in the US Army inventory.

The first of these new wheeled tank destroyers to arrive in March 1942 for testing by the Ordnance Department was a 6 × 6 Ford product designated the T22 tank destroyer. That same month, the US Army relabelled it and the other four candidate vehicles, not yet delivered for testing by the Ordnance Department, as light armoured cars, rather than as tank destroyers.

This change in titles reflected the fact that British Army combat experience gained in North Africa in early 1942 clearly demonstrated that a 37mm anti-tank gun was no longer adequate on the modern battlefield. However, fitted on a reconnaissance vehicle it offered enough firepower for its intended role as envisioned by the US Army at that time.

By early 1942, the US Army was desperate for an affordable light armoured car that could be built quickly, and in large numbers. Because the T22 performed so well during its initial testing period with the Ordnance Department, almost all concerned with the project agreed that with some minor modifications it should be quickly standardized and placed into production.

The T22 would be rushed through development by the US Army despite the fact that four other candidate vehicles had not yet even been delivered for testing. These included a Ford-designed and built 4 × 4 labelled the T22E1. The Fargo Division of General Motors had submitted two vehicles, the 6 × 6 T23 and the 4 × 4 T23E1.

The modified version of the T22 chosen by the US Army for production was designated the T22E2. In May 1942, Ford was awarded a contract to build the T22E2, which was standardized as the Light Armored Car M8 in June 1942. Combat loaded, the vehicle weighed 17,400lbs; un-stowed, it weighed 14,500lbs.

The decision to order the M8 Light Armored Car into production was later concurred upon by the Special Armored Vehicle Board, which believed that despite some design flaws, and being a bit heavier then desired, it was the best available vehicle at that time.

Due to unresolved contract issues between the US Army and Ford, production of the M8 Light Armored Car did not begin until March 1943. Prior to that time, a number of modifications were made to the vehicle’s design. These included the replacement of the original cast armour turret with a new welded armoured turret. Improvements were also made to the vehicle’s front suspension system.

By the time production of the M8 ended in May 1945, a total of 8,532 units had been completed. A total of 1,205 units of the vehicle would be allocated to Lend-Lease, with the largest number going to the Free French Army, which received 689 units. In British Army service the vehicle was assigned the name ‘Greyhound’.

The majority of M8 Light Armored Cars would serve with US Army mechanized cavalry units during the Second World War. They were organic to armoured divisions and tank destroyer battalions, but non-organic to infantry divisions. Post-war, the US Army did away with the title mechanized cavalry and simply referred to those units tasked with the reconnaissance mission as the ‘cavalry’, or just the ‘CAV’.

From a 24 February 1944 War Department (the predecessor to the United States Department of Defense) manual titled Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized) comes this description of the M8 Light Armored Car and its role:

Armored Cars are the basic command and communication vehicles. The Light Armored Car, M8, is a 6 × 6 vehicle, weighs 16,400 pounds with equipment and crew, and is capable of cruising from 100 to 250 miles cross country or 200 to 400 miles on highways without refuelling. On a level, improved road, it can sustain a speed of 55 miles per hour. Each armoured car is equipped with a long-range radio set to assist in the exercise of command or for the purpose of relaying information received from subordinate elements to higher headquarters, and a short-range radio set for communication with a platoon, reconnaissance team or headquarters.

As the M8 Light Armored Car was designed with standard truck-type suspension components, to keep its cost down, its off-road performance was extremely limited. This fact was of great concern to many within the US Army prior to the vehicle being standardized and would remain a problem for many throughout the war years.

Major General Robert Crow, commander of the 6th Armored Division, so disliked the M8 Light Armored Car that he replaced them within his division, and even as his own command vehicle, with the full-tracked 75mm Howitzer Motor Carriage (HMC) M8.

From an After Action Report of the 640th Tank Destroyer Battalion that fought in the Philippines between January and March 1945 comes this comment: ‘The M8s and M20s in reconnaissance companies proved to be very good reconnaissance vehicles over terrain where a road net existed, however, over difficult terrain their ability to reconnoitre for tracked vehicles is very limited.’

In contrast, Lieutenant Colonel Michael Popowski, who commanded an M8 Light Armored Car equipped unit in the Italian Theatre of Operations, stated in a 7 October 1944 US Army report these positive comments: ‘During my combat experience I saw only one instance where the armoured car was not able to go where the tanks went . . . Some of its capabilities over a tracked vehicle are: quietness, range, maintenance, and weight, which are all important in reconnaissance.’

Despite some positive comments on the employment of the M8 and M20, the general consensus on the vehicle’s merits were summed up in this statement by the Ordnance Department at the conclusion of the Second World War:

The armoured cars M8 and M20 had varied acceptance in this theatre [Western Europe]. However, on the whole, using organizations were not satisfied with the performance of these vehicles as they felt they were under-powered, lacked manoeuvrability, sufficient floatation for cross-country operation, and sufficient armoured protection. These vehicles were not reliable, resulting in excessive quantities dead-lined in maintenance shops for repair.

The Tank Destroyer Command identified a need for a turret-less version of the M8 Light Armored Car. Their requirement was authorized and Ford was awarded a contract to build a vehicle that was designated as the Armored Utility Car M20.

The M20 Armored Utility Car was standardized in May 1943, and would serve in a number of roles, including command car, personnel carrier and cargo carrier. Ford began M20 production in July 1943; at the conclusion of production in June 1945, a total of 3,791 units had been manufactured.

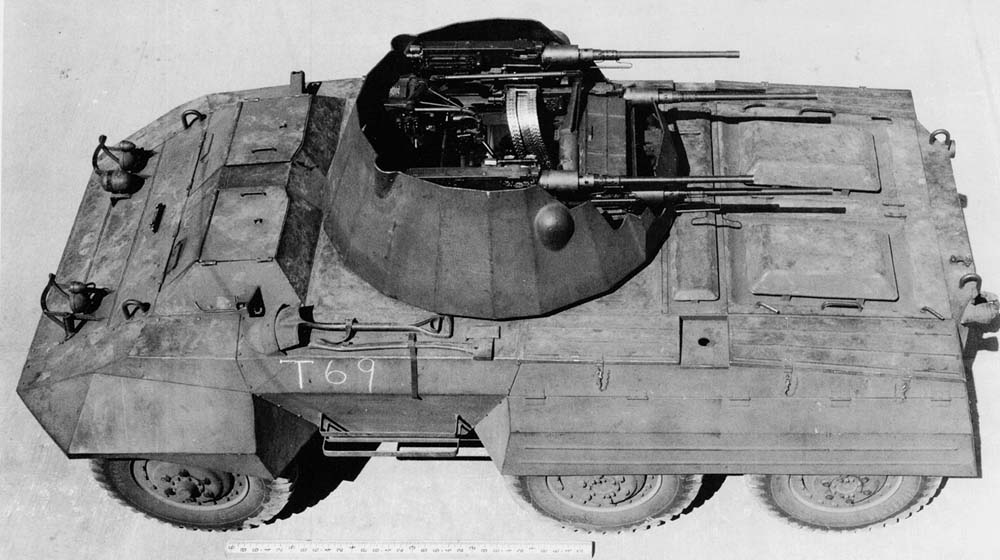

Variants of the M8 Light Armored Car that were not placed into production included the Multiple-Gun Motor Carriage T69 and the Armored Chemical Car T30. The T69 featured an open-topped turret armed with four large-calibre machine guns. The T30 never made it off the drawing board. It would have consisted of a standard M8 Light Armored Car fitted with five 7-inch rocket launchers on either side of the vehicle’s turret.

Despite not being invited by the US Army to provide a light armoured car for testing by the Ordnance Department, the Studebaker Corporation did so anyway. The 6 × 4 vehicle they submitted was labelled as the T43. With the acceptance of the M8 Light Armored Car for production, the Studebaker submission, as those provided by Ford and General Motors, never went past the prototype stage.

Another light armoured car that did not make it into production was a variant of the T14 tank destroyer. It had been requested by the Tank Destroyer Command and dubbed the Scout Car T24. It was approved for production by the Special Armored Vehicle Board, but it was disapproved at a higher level.

As a replacement for the M8 Light Armored Car, the Special Weapons Board recommended the development of another light armoured car of the same size and weight, but fitted with an independent suspension system.

As a result of the US Army’s interest, Studebaker submitted an 8 × 6 vehicle labelled the T27 Light Armored Car. The Chevrolet Division of General Motors submitted a 6 × 6 vehicle, assigned the designation T28 Light Armored Car. Testing of these two experimental light armoured cars showed that both had superior off-road performance to the M8.

Of the two proposed replacements for the M8 Light Armored Car, the off-road performance of the T28 was superior to its 8 × 6 counterpart the T27. This resulted in any additional development of the T27 being cancelled.

There also arose a call for standardizing the T28 as the Light Armored Car M38 in December 1944, once necessary modifications were made to the vehicle’s design. The vehicle combat-loaded weighed 15,300lbs. The end of the Second World War in August 1945 resulted in cancellation of the vehicle before production could commence.

With America’s official entry into the Second World War, there was a frantic effort to greatly increase the number of wheeled and tracked AFVs being built. This resulted in a push to field light, medium and heavy armoured cars that would meet both US and British Army requirements. Pictured is the Ford-designed contender for a medium armoured car that the Ordnance Department labelled the T17. (TACOM)

In the March 1942 Table of Organization and Equipment (TO&E) proposed for US Army armoured divisions, there was a requirement for forty-nine armoured cars to perform reconnaissance duties. What had not been decided at that time was what type of armoured car would be acquired as all were still in development, including the Ford-designed T17 medium armoured car pictured here. (TACOM)

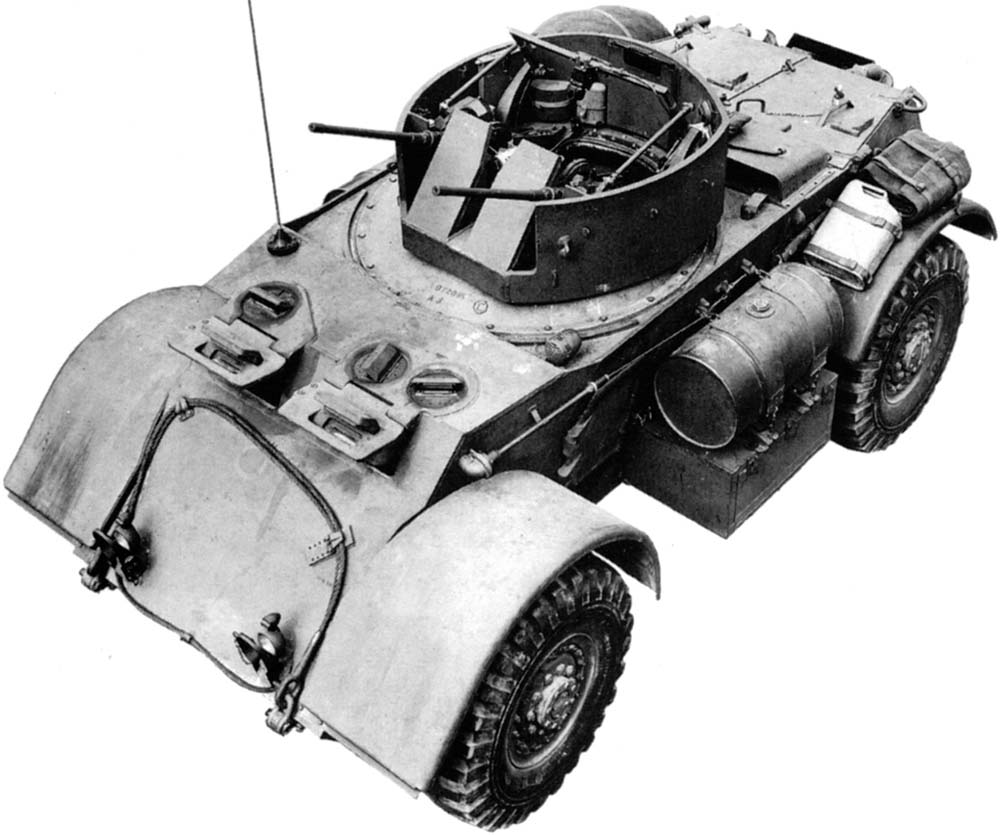

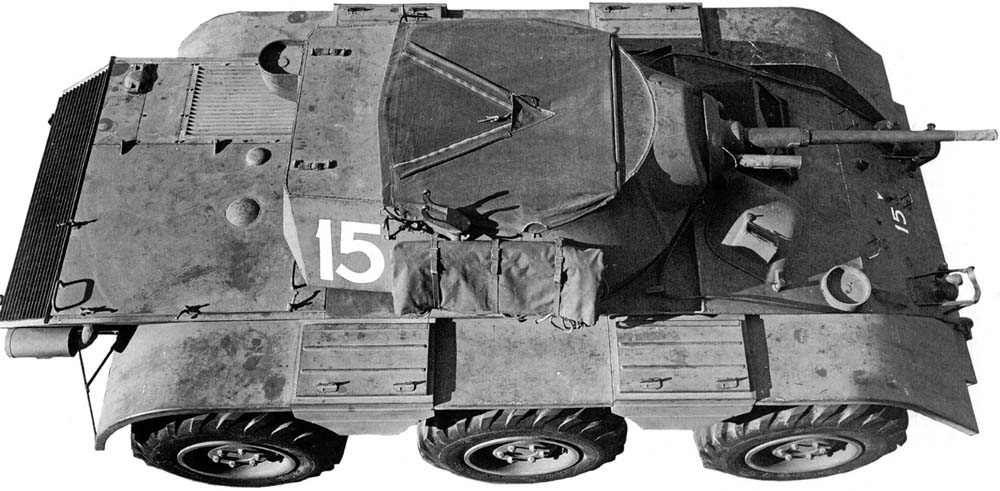

The other contender for supplying the US and British Army with a suitable medium armoured car was the General Motors Corporation, which provided a vehicle designated the T17E1 seen here. The vehicle had some advanced design features such as an automatic transmission, but still rode on commercial truck axles and leaf springs, which greatly hindered its off-road mobility. (TACOM)

The large external fuel drum visible on this unrestored General Motors Corporation T17E1 Medium Armored Car pilot also existed on the other side of the vehicle. This was a British Army requirement to increase the range of the vehicle, which reflected its experience gained fighting the Axis in North Africa. The approximate cruising range of the T17E1 on roads was 450 miles. (Chris Hughes)

The pilot model of the General Motors Corporation T17E1 Medium Armored Car seen here lacked the small rounded opening for the 2-inch smoke mortar that appeared on the right front of the turret roof on series production units of the vehicle. Advanced features of the vehicle included an automatic transmission and power steering. (TACOM)

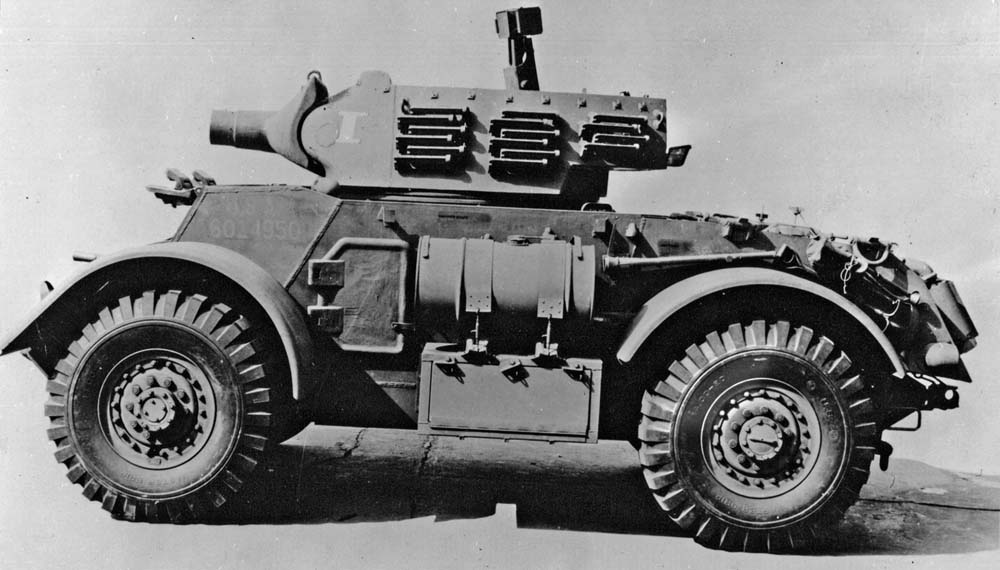

A series production model of the T17E1 Medium Armored Car, which was named the ‘Staghound’ by the British Army. It lacks the large pistol ports that were seen on either side of the turrets on the pilot units of the vehicle. The vehicle had a height of 9 feet 3 inches, a length of 18 feet, and width of 8 feet 8 inches. (TACOM)

In the markings of the postwar Belgian Army is a restored example of a series production T17E1 Medium Armored Car. Power for the vehicle was provided by two commercial truck engines that each produced 95hp, giving the vehicle a top speed on level roads of 55mph. The vehicle was able to cross a trench 1.5 feet in width, climb over a vertical wall 21 inches high, and had a maximum fording depth of 32 inches. (Michael Krauss)

An anti-aircraft variant of the T17E1 Medium Armored Car built and tested in the United States per a British Army request. It was designated the T17E2 by the Ordnance Department. The British Army named it the ‘Staghound AA’ (anti-aircraft). It was armed with two air-cooled large-calibre machine guns mounted in a power-operated turret. (TACOM)

Another variant of the T17E1 Medium Armored Car built and tested in the United States per a British Army request. It was designated as the T17E3 by the Ordnance Department and consisted of the turret of the US Army 75mm Howitzer Motor Carriage M8 mounted on the chassis of the standard T17E1 Medium Armored Car. (TACOM)

In January 1942 the US Army authorized the funding for the development and testing of the Medium Armored Car T19. In contrast to the commercial truck-type suspension systems on the T17 and T17E1 Medium Armored Cars, the T19 was fitted with an independent suspension system. Except for its suspension system it was very similar to the T17 and T17E1 Medium Armored Cars. (TACOM)

Testing of the T19 Medium Armored Car began in October 1942. These tests led to the construction of a modified version of the T19, pictured here, labelled as the T19E1 Medium Armored Car. The T19E1 was fitted with the powertrain of the US Army’s M5 Light Tank, which included two Cadillac engines as well as an automatic transmission. (TACOM)

Pictured during off-road testing is the T19E1 Medium Armored Car. It had a redesigned and lighter turret than that mounted on the T19, but was still armed with a 37mm main gun. The independent suspension systems on the T19 and T19E1s proved far superior to the commercial truck-based suspension systems found on other US Army armoured cars. (TACOM)

There was a single variant of the T19E1 chassis as seen here. It was labelled as the T66 75mm Gun Motor Carriage, which was a tank destroyer by any other name. The vehicle had been proposed by the US Army in November 1942, but cancelled in March 1943 along with the T19 and T19E1 Medium Armored Cars. (TACOM)

Once considered for use by both the US and British Army was the T18E2 Heavy Armored Car. Named the ‘Boarhound’ by the British Army, it was armed with a 57mm main gun. Series production of the four-man vehicle began in December 1942, with two being built that month. A total of thirty were completed by May 1943 before being cancelled. (TACOM)

Despite the cancellation of the T18E2 Heavy Armored Car by the US Army, the British Army continued to express interest in the vehicle and eventually all thirty built were shipped to Great Britain under Lend Lease. Other than some testing, the British Army decided that it would not be committed to combat. (TACOM)

The US Army began a crash programme in early 1941 to develop and quickly field as many stop-gap wheeled tank destroyers as possible. One of these lines of development led to the fielding of the M6 seen here. It was officially labelled by the US Army as a gun motor carriage. The only armour on the vehicle was the shield that protected the 37mm anti-tank gun and its crew. (TACOM)

When first conceived it remained unclear to the US Army if the shield-protected 37mm anti-tank gun on the M6 tank destroyer would be better suited to fire over the front or rear of the vehicle. Testing quickly led to the conclusion that the gun aimed to the rear was a better choice, as the muzzle blast from the weapon when fired over the front of vehicle was too hard on the driver. (TACOM)

A truly novel approach to mounting an anti-tank gun, supposedly of sufficient size to deal with German medium tanks, was the 3-inch GMC that was designated as the T55E1. It and an earlier version labelled the T55 were both tested in 1943, but neither could match the off-road mobility of fully-tracked armoured vehicles armed with the same weapon and were therefore rejected by the US Army. (TACOM)

In the summer of 1941, in pursuit of a next-generation wheeled tank destroyer to replace the stop-gap M6 GMC, the US Army solicited proposals from two different companies to see what they could come up with. By the time the first candidate vehicle arrived for testing, the Ford T22 (pictured) and the yet-to-be-delivered candidate vehicles were all re-labelled as light armoured cars. (TACOM)

The US Army felt the Ford T22 Light Armored Car had a lot of potential, and by tweaking the design a bit they came up with another pilot model of the vehicle designated as the T22E2. It was this pilot vehicle that the US Army decided to standardize as the M8 Light Armored Car; a restored example is pictured. (Christophe Vallier)

A major design difference between the T22E2 Light Armored Cars and the majority of series production M8 Light Armored Cars was the latter’s welded open-topped turret. The open-topped turrets on the T22E2 and the very early series production M8 were castings. Notice the bracket between the front and rear wheel fenders for the storage of three anti-tank mines, seen on this restored example. (Christophe Vallier)

Reflecting the very thin armour on the M8 Light Armored Car, the thickest portion being the gun shield at one inch, the crew of this vehicle has added a large number of sandbags to the front hull. The sandbags are held in place by a supporting bracket of the front hull. The driver has a sub-machine gun at the ready for any close-in threat to the vehicle. (Patton Museum)

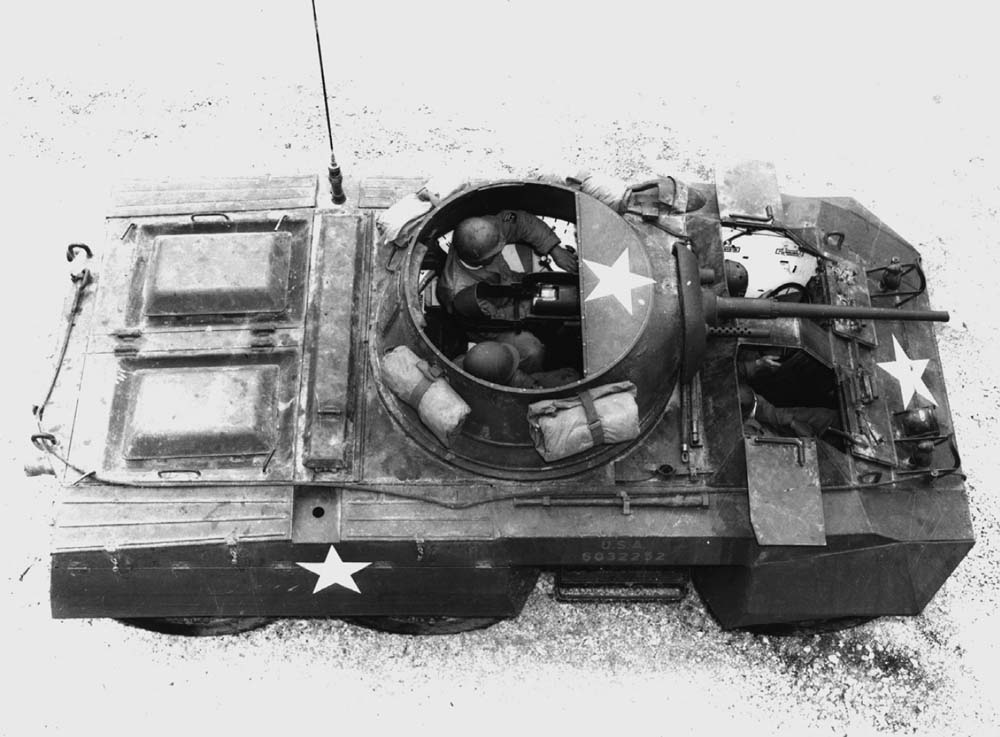

An overhead shot of a series production M8 Light Armored Car, with its crew of four. Due to the small size of the vehicle’s turret, the vehicle commander doubled as the loader for the 37mm main gun. There was storage space for eighty rounds of 37mm ammunition on the M8. It was 16 feet 5 inches long, 8 feet 4 inches in width and had a height of 7 feet 4 inches. (TACOM)

This M8 Light Armored Car is on patrol in the Netherlands in September 1944. It is armed with a large-calibre machine gun fitted to a ring mount, allowing the operator to traverse the weapon 360 degrees. Also visible is the coaxial small-calibre machine gun fitted alongside the 37mm main gun. (Patton Museum)

Due to the extremely cramped nature of the turret on the M8 Light Armored Car, the vehicle commander sometimes would aim and fire its large-calibre turret-mounted machine gun from outside the confines of the vehicle’s turret. Armor thickness on the vehicle’s turret, not including the gun shield, was only 19mm. (Patton Museum)

Sporting the remains of a lime whitewash winter camouflage scheme is a US Army M8 Light Armored Car in Belgium during the Battle of the Bulge. The upper front hull armour on the vehicle was 16mm thick, and the lower front hull 19mm. The hull sides of the M8 were only 9mm thick. There was no armour on the hull floor on the vehicle, which led crews to often line the bottom floor of the vehicle’s crew compartment with sandbags. (Patton Museum)

The Ordnance Department believed the various ring mounts employed on the M8 Light Armored Car for the vehicle’s turret-mounted large-calibre machine gun lacked the necessary strength and durability. The end result was the fielding in late 1943 of a new pintle bracket mount for the large-calibre turret-mounted machine gun fitted to the rear of the vehicle’s turret, as pictured. (TACOM)

As seen in this official Ordnance Department picture, the new pintle bracket mount for the large-calibre turret-mounted machine gun on late series production M8 Light Armored Cars could be folded down. The exposed external bracket that once held three anti-tank mines on either side of the vehicle has been replaced by a large unarmoured storage bin. (TACOM)

The Tank Destroyer Command of the US Army issued a requirement for two wheeled vehicles, both to be based on the M8 Light Armored Car chassis. One was to be an armoured command car and the other an armoured personnel carrier, which could also do double-duty as an ammunition carrier. Ford decided that only one vehicle was needed and came up with the T26 Armored Utility Vehicle, pictured here. (TACOM)

The US Army concurred with Ford that the T26 Armored Utility Vehicle could satisfy both of the Tank Destroyer Command’s requirements, and went ahead and eventually standardized it as the M20 Armored Utility Vehicle. A restored example is pictured. Notice that the bracket for supporting the ring mount for the large-calibre machine gun is different from that on the T26. (Michael Green)

A restored example of an M20 Armored Utility Vehicle owned by a private collector. The vehicle was originally designated as the M10 Armored Utility Vehicle by the Ordnance Department. However, this caused confusion when it was assigned to tank destroyer units equipped with the M10 Tank Destroyer. This pushed the Ordnance Department to re-label it as the M20. (Michael Green)

Taken somewhere in Western Europe is this picture of an M20 Armored Utility Vehicle. Notice the improvised ring-mount for the large-calibre machine gun. Not all M20s were fitted with ring mounts and their associated weapons, as many were only employed in rear area duties. The open top arrangement of the design meant that many units made improvised canvas shelters for the vehicles as protection from inclement weather. (Patton Museum)

In search of a better ring mount for the M8 Light Armored Car and the M20 Armored Utility Vehicle, the Ordnance Department developed the T86 Ring Mount. Rather than test its durability with a single large-calibre machine gun, the Ordnance Department borrowed a twin large-calibre machine gun from the US Navy, as pictured. It must have passed its tests as it eventually resulted in the M66 Ring Mount, which appeared on late production M20s. (TACOM)

A rejected variant of the M8 Light Armored Car was the T69 Multiple Gun Motor Carriage. It was optimized as an anti-aircraft vehicle but could have also been used in a ground support role. Its one-man turret was armed with four large-calibre machine guns. Testing of the vehicle did not go well and the US Army decided to stick with its half-track-based anti-aircraft vehicles. (TACOM)

Despite not being asked by the Ordnance Department to submit a pilot vehicle in its quest for a suitable light armoured car, the Studebaker Corporation went ahead and submitted a vehicle anyway, seen here, that the Ordnance Department designated as the T21. The decision by the US Army to go forward with a modified version of the Ford T22 design meant the Studebaker project never went anywhere. (TACOM)

The T24 Scout Car was something the Tank Destroyer Command saw a requirement for in early 1942. It was based on the same design as a proposed tank destroyer that the Ordnance Department had labelled as the 37mm Gun Motor Carriage T14. In the end, neither vehicle was approved for series production. (TACOM)

Well aware of the design limitations of the commercial truck-type suspension system on the M8 Light Armored Car, the Ordnance Department indicated to private industry a desire to see a next-generation replacement for the M8, which would feature an independent suspension system. The Studebaker submission designated as the T27 Light Armored Car is pictured. (TACOM)

The General Motors Corporation contender for an M8 Light Armored Car replacement. It was labelled as the Light Armored Car T28 by the Ordnance Department. Testing of the Studebaker T27 alongside the General Motors T28 led to the conclusion that the latter was the superior vehicle and should be approved for series production by the US Army as quickly as possible. (TACOM)

Once approved for standardization by the US Army, the General Motors T28 was re-designated as the Light Armored Car M38. Such was the anticipation that the vehicle would quickly be placed into production, the British Army assigned it the name ‘Wolfhound’. With the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, the M38 was cancelled before production commenced. (TACOM)

A one-of-a-kind wheeled AFV employed by the US Army Air Forces during the Second World War that was not designed and built in the United States is the S-1 Scout Car. It was an Australian-designed armoured body mounted on a 4 × 4 military cargo truck chassis. It was intended to be used to guard American air bases in Australia, and it is reported that approximately forty were built. (TACOM)