THE CANNABIS PLANT

Cannabis evolved from plants native to the high altitudes of the Tibetan plateau and the Himalayan foothills. Its origins are clouded by the plant’s early symbiotic relationship with humans, a relationship at least 6,000 years old. The use of cannabis and its products migrated with humans throughout the world, and the plant is now cultivated in climatic zones from the Arctic to the equator. Cannabis evolved on its own prior to its discovery by our human ancestors, but since then, it has been bred intensively to optimize particular characteristics.

Cannabis is cultivated for one or more of three useful products:

- the nutritious seeds

- the fibrous stalks

- the resinous flowers

Cannabis seeds are rich in oil and protein and are used as a food and as animal feed, as well as a source of oil for fuel and skincare products. The seeds have almost as much protein as soybeans, and they provide all nine of the essential amino acids that humans cannot create on their own and must obtain through diet. The lipid profile of the seeds is high in polyunsaturated fatty acids, especially omega-3 fatty acids. The seeds are also substantial sources of dietary fiber.

Cannabis fiber, produced from the stalks of the plant, is used to make tough cloth, paper, and rope. Though all cannabis plants are of the same species, the varieties typically cultivated for their seeds or fiber are known as hemp.

The third product, the flowers and the resin that coats them, is used therapeutically and recreationally. Cannabis resin contains the group of substances collectively known as cannabinoids, of which Δ9 Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chief psychoactive component. THC and at least 143 other cannabinoids are unique to cannabis. Plants grown for their THC content are commonly called cannabis, whereas cultivated varieties of cannabis that are primarily grown for their fiber and seed products are commonly referred to as hemp.

The many uses of this multifaceted plant have historically made it a valuable crop, and today there are collectively more breeding programs for cannabis than any other crop. The historical illegality of cannabis has unintentionally resulted in a robust breeding program that is pushing the genetic limits of what cannabis can produce as far as cannabinoid and terpene content, yield, and more. The escalation of the US government’s War on Drugs forced innovative cultivators and breeders to work underground to provide a sufficient supply of seedstock to serve their own needs. The War on Drugs restricted transport of cannabis from Mexico, so American cultivators had to get creative in sourcing. Because of seed scarcity in the commercial market and the fact that cannabis is one of the few plants that casual farmers and breeders can easily grow from self-produced seed, many gardeners have become self-reliant and created their own seed stock.

Gardeners who take this path join an international breeding program as soon as they transfer some of their genetics (i.e., seeds) to someone else. In the 50 years of this modern cannabis breeding program, growers have developed diverse varieties and cultivation methods that are quite efficient at producing the desired product: large, dense buds of sinsemilla—that is, a profusion of unpollinated female flowers.

Cannabis varieties differ in many ways, including growth characteristics such as:

- height

- width

- branching traits

- leaf size and shape

- flowering time

- yield

- potency

- taste

- physical and mental effects

- aroma

- cannabinoid and terpene profile

The final harvest of a plant is a result of its “nature” and “nurture.” The potential for high-potency cannabis is determined by genetics, or nature. However, environmental conditions, or nurture, affect the plant’s growth and yield. Some plants have the genetic potential to produce high-quality cannabis and others do not. The goal of the cultivator is to provide the optimal environment to nurture the plants so they reach their full genetic potential.

Cannabis is a fast-growing annual plant, although some varieties in warm areas can overwinter by going dormant as the days shorten, then grow and flower again the next summer. The plant evolved on the Tibetan plateau, where the altitude averages 10,000 feet (3,000 m). Cannabis has evolved to grow, flower, and seed before the autumn snow in order for the population to survive to grow the following season.

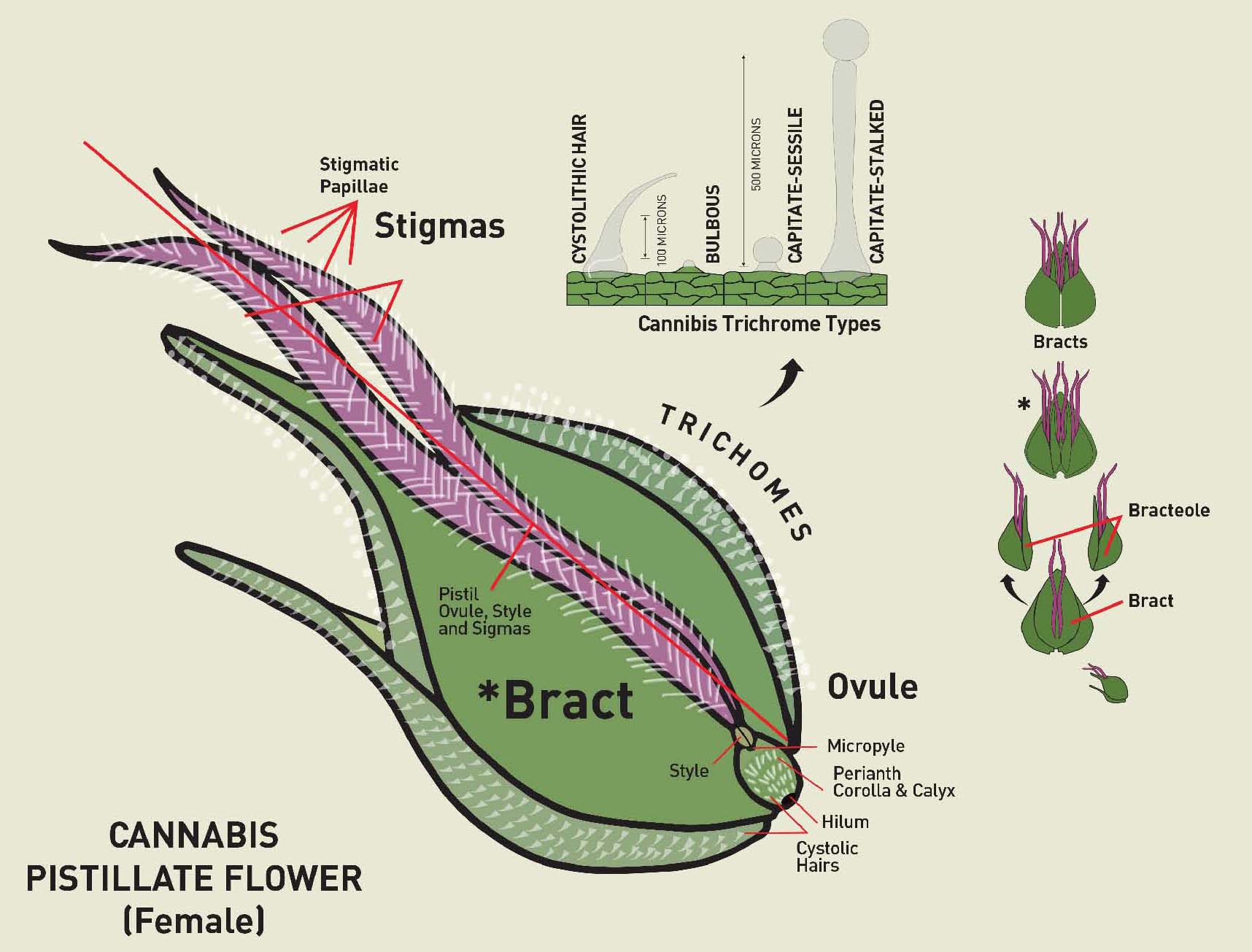

Cannabis does best in a well-drained, nutrient-rich growing medium and requires long periods of bright, unobstructed light daily. Cannabis is usually dioecious, meaning plants are either male or female. Annual dioecious plants are rather unique in the plant kingdom.

Occasionally monoecious plants, or hermaphrodites, appear and produce both male and female flowers; however, this is often a function of a plant being stressed to induce hermaphroditism. Hermaphroditic plants are most common among some varieties native to south Asia, but can also result from inadequate light, poor nutrition, or switching from long uninterrupted nights to short or interrupted dark periods and back again. Because monoecious plants produce male flowers that can pollinate females, they are undesirable and should be removed from the garden as soon as they appear to avoid a pollination event.

Cannabis grown in the wild or with traditional methods outdoors has an annual cycle that begins with seed germination in the early spring. The plant grows vigorously in a vegetative state for several months as the days get longer and they begin to flower as the lengthening darkness reaches a critical period in late summer or early fall.

The flowering time of landrace varieties depends on the variety’s native latitude, but occurs in late summer as the night length increases. Most indicas are varieties from high latitudes and need less darkness to flower than most sativas, which are varieties from lower latitudes and equatorial regions. Most varieties set seed in the fall because they are genetically programmed to start flowering when the dark period reaches a critical length of time on consecutive nights of uninterrupted darkness. As winter approaches, the seeds drop and are ready for the next season as the plant dies.

Controlled environment agriculture, as seen in indoor or greenhouse production, allows the cultivator to control when the plants receive the critical length of uninterrrupted dark period. This gives the grower the ability to determine when the plants will be forced to flower, and when they will be ready to harvest.

Botanical Description: Cannabis sativa L.

The word “cannabis” is an ancient one, dating back past Roman and Greek to Thracian or Scythian times. Scholars have even identified biblical references to a plant known as “kaneh-bos” as early as the 15th century BCE.

As the contemporary name of a type of plant, Cannabis sativa L. was formally conferred in 1753 by Carolus Linnaeaus in his famous taxonomy. Linnaeaus, who devised the modern system for classifying and naming species through binomial nomenclature, concluded that the genus Cannabis had but one species, which bears the same botanical name. The genus is currently classified as belonging to the Cannabaceae family, which also includes hops (Humulus sp.). Recent phylogenetic studies and gene sequencing suggested that Cannabis sativa L. is closely related to members of the Celtidaceae family, which also includes the many species of Hackberry tree (genus Celtis); however, plant taxonomists have recently moved the members of the Celtidaceae family under an expanded Cannabaceae family. This was not the first time that Cannabis sativa L. has been reclassified, as it was formerly categorized as part of the Nettle (Urticaceae) or Mulberry (Moraceae) family.

There has been a similar evolution of thinking on how many species of Cannabis sativa L. should be recognized. In 1785, soon after Linnaeus identified it as a single species, the influential biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck claimed that the plant he found in India should be classified as a separate species, which he named Cannabis indica. This name would be included in various pharmacopoeias to designate cannabis plants that are suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.

In the 19th century, some botanists proposed separate species classifications for cannabis plants indigenous to China and Vietnam. But by the 20th century, difficulty with definitively distinguishing between any of them due to intense breeding and hybridization had led most botanists to conclude, as Linnaeus did, that all cannabis plants belong to a single species.

What was once known as Cannabis indica would now be classified as a subspecies of Cannabis sativa (Cannabis sativa subsp. indica). Certainly, all cannabis plants satisfy one of the chief criteria of a species: they can interbreed. There are different ways to define a species. Wide disparities in cannabis plants’ geographic location and primary characteristics have led many to argue that three species should be recognized, based on whether they are cultivated for fiber (sativa) or drugs (indica), or grow wild (ruderalis); however, defining a species by its ability to interbreed or hybridize has led taxonomists to conclude that sativas and indicas fall under one species.

Although it has been speculated that ruderalis is the progenitor wild variety, the fact that most of its alleles are recessive is an indication that it is a mutation. Although ruderalis can be hybridized with sativas and indicas, it grows in a fundamentally different manner and looks very different from the other members of the genus. For instance, flowering in ruderalis begins soon after germination and is not dependent on the length of daylight. Breeding cannabis varieties with ruderalis can create new varieties that will automatically start flowering (“autoflowering”) regardless of the length of uninterrupted darkness. With careful breeding the hybrids will retain their highly resinous nature, as ruderalis is not typically as resinous as sativas or indicas.

The genetic makeup of cannabis varieties, also known as the genotype, is what drives the cannabinoid and terpene profile of the plant. The physical expression of the genotype is referred to as the phenotype. The plant’s phenotype includes physical traits like plant height, yield, leaf size, terpene profile, cannabinoid ratios, flavonoid content, and time to harvest. The chemotype is the plant’s phenotype, but specifically in reference to the chemical makeup of the plant. In other words, the chemotype of a cannabis variety is the genetic expression of its chemical makeup: cannabinoid potency, ratios, and content, terpene profiles, and flavonoid content.

The diversity of the cannabis plant’s geography and morphology is considerable; cannabis grows in very different ways and places. The stems reach a height between three and 15 feet (~1 and 4.5 m) or more, and the plants range from thin and reedy to thick and bushy. While the plant is native to the Hindu Kush valley and the Himalayan foothills of the Tibetan Plateau, it has migrated with humans throughout the world and can now be found growing feral on every continent but Antarctica. Since there are no laws prohibiting it in Antarctica, where researchers from many countries work, it is safe to assume that cannabis has spread its roots there, too.

Cannabis sativa L. is one of only a few dioecious annual plants (including spinach)—that is, each plant is distinctively either male or female—though hermaphrodite plants do occur. Also unusual is the fact that cannabis is an annual, yet its closest botanical relative, hops, is a perennial. That, combined with the cannabis plant’s ability in Nepal and similar climates to overwinter or regenerate in spring suggests that the plant’s evolutionary path from being a perennial to an annual may have been relatively recent.

Even the plant’s iconic leaves, instantly recognizable even to those who have never seen a cannabis plant growing, come in very different sizes and subtly different shapes. The palmate leaves can range from a spread of a few inches (about 5 cm) to more than a foot (30.5 cm), while the one to 13 (or more) sharply serrated leaflets vary from long and thin to broad and stubby. The cannabis plant’s combination of extreme genetic variability and ease of interbreeding is part of what makes it so exciting to grow. The range of characteristics that selective breeding can produce is astonishing.