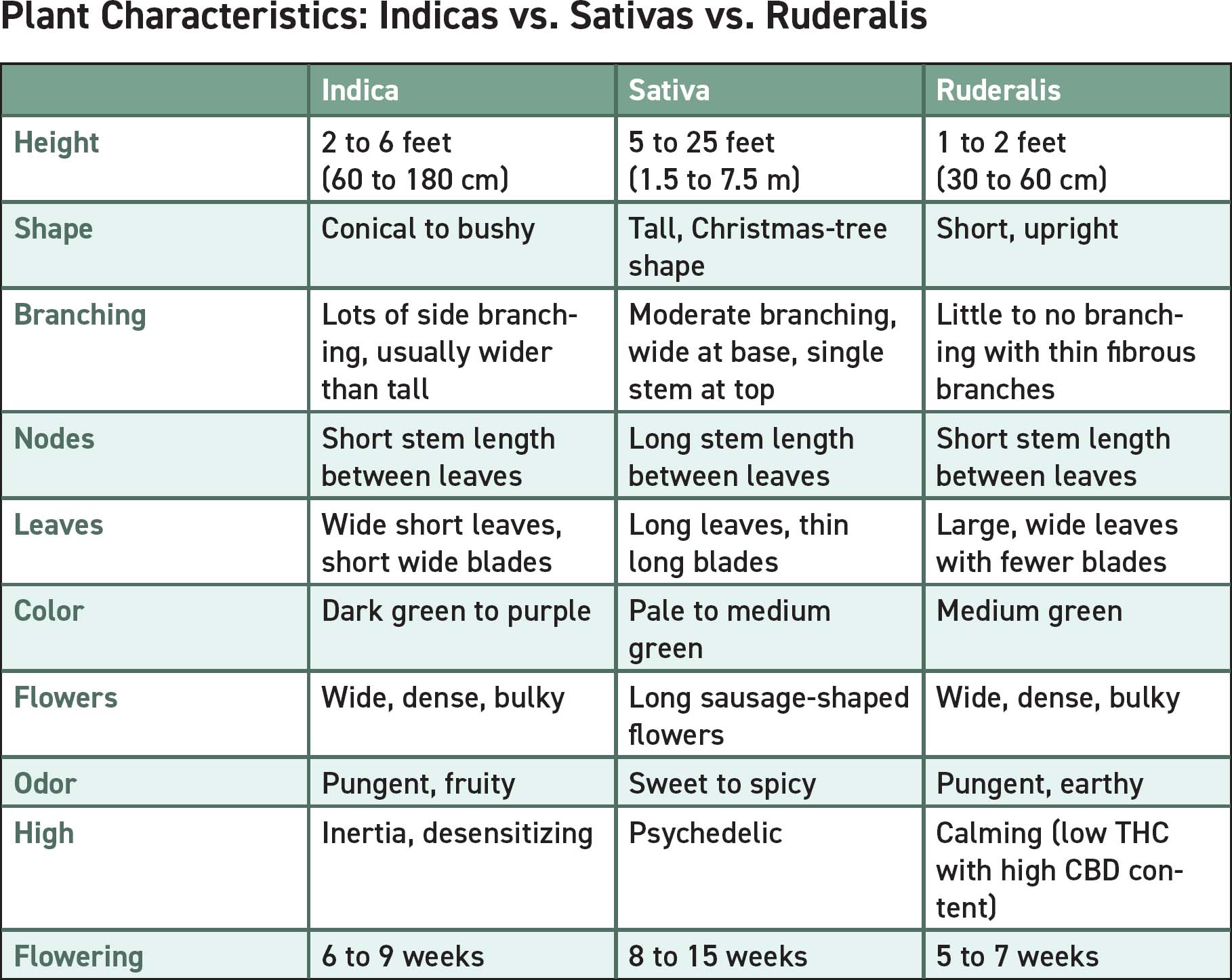

INDICA, SATIVA, RUDERALIS & HYBRIDS

Most cannabis grown in the United States is derived from the hybridization of three distinct groups of cultivars: sativa, indica, and ruderalis. These groups were geographically separated and evolved along different paths to best survive in different environments.

Plant varieties originating in lower latitudes have less variation within their population. The reason is that the weather patterns, temperature, and rainfall in equatorial areas tend to vary less year to year. An equatorial population can home in on a more specific type of environment. As a result, the plants that thrive in a geographic location with little varying environmental factors will lead to a homogeneous genetic profile in the population.

All of these are sativas. They tend to grow tall so they can maintain their positions capturing light at the top of the canopy. They have long branches with thin leaves, since the light is so intense that the leaves don’t have to grow wide to capture it. They have fewer chloroplasts because they don’t need as many, when the light keeps the ones they have working at full speed. For this reason, equatorial leaves look paler than temperate plants’ leaves. Since these plants are growing in areas where there isn’t a threat of a freeze, they can take their time flowering and maturing. The landrace cannabis cultivars from equatorial regions show more homogeneous growing patterns as a result of evolving in more consistent environmental conditions.

In temperate climates there is wider variability in weather—one year may be cold and rainy, the next hot and dry. In order to cope with this variability, temperate region cannabis populations evolved a more heterogeneous gene pool, so plants with one set of genes do better one season and another set does better under different conditions. That way, both the population and the genes are preserved. The landraces that have a more genetic variability evolved around the 35th parallel north. These include Southern Africans, Northern Mexicans, Moroccans, Lebanese, Nepalese, and Hindu Kush.

Plants within these groups look slightly different from each other and have different maturities, cannabinoid profiles, and potency. The variation in climate in midlatitude temperate zones explains their heterogeneity, the same as the higher latitudes’ variation in climate affects the heterogeneity of cannabis found there.

Midlatitude varieties exhibit a wider selection of adaptations to cope with the variety of climatic challenges they face. This prepares them for unique weather conditions that may occur in an abnormal growing season.

Most cultivated varieties grown for commercial purposes are derived from hybrids of these types of cannabis. Starting in the 1970s, breeders crossed different varieties from the midlatitudes to combine the best characteristics from those populations to create some of the first domestic cannabis varieties, including Afghani-Kush, Big Bud, Haze, Hash Plant, Northern Lights, Skunk #1, and William’s Wonder. These first domesticated varieties were derived from Afghani, Indian, Colombian, Mexican, Thai, and Vietnamese cannabis. A second generation of breeders included landraces from Brazil, South Africa, and Burma.

Within a few years, breeders started working with these domesticated varieties to hone the hybrids and find novel cannabis with desired characteristics, such as more sophisticated and complex highs, fast maturity, uniform flower development, bigger buds, larger yields, higher cannabinoid potency, pest resistance, more compact growing style, and so forth. Most of the varieties offered today are many hybridizations away from the original landraces from which they started. They have been totally domesticated to modern standards and tastes.

Indica

As noted above, indica plants developed in central Asia between the 25th and 35th parallels north, where the weather is variable. Cannabis evolved in this region to reflect the variable weather patterns by developing a variety of different populations to cope. Thus, in any season, no matter what the weather, some plants will do better than others.

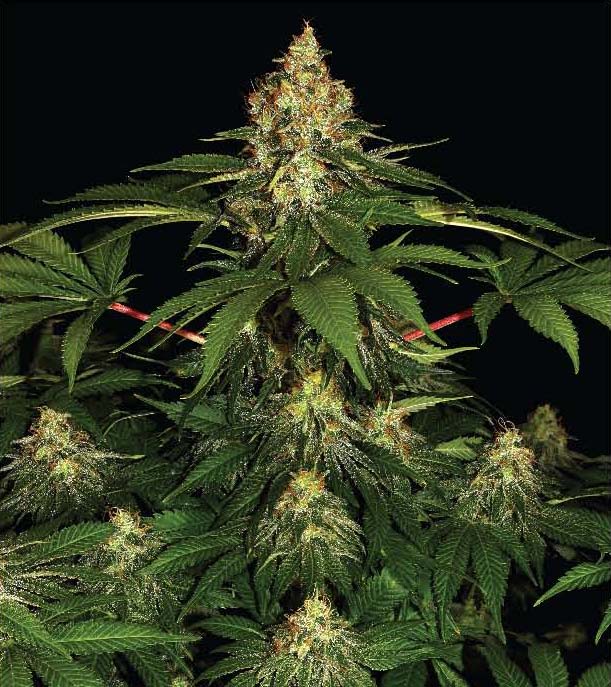

100% Indica Shiskaberry by Barney’s Farm

Indicas, including Kush varieties, tend to have broad general characteristics: they mature early, have compact short branches and wide, short leaves that capture much more light than thin leaves, which are dark green, an indication of the high number of chloroplasts in the leaves needed to most efficiently capture light energy. Their buds are usually tight, heavy, wide, and thick, rather than long. They smell “stinky,” “skunky,” or “pungent,” and their smoke is thick—a small toke can induce coughing.

Indica plants were bred to develop varieties of cannabis for resin content, which was removed from the flowers to make hashish. It was only after these varieties found their way to the Americas were their buds widely consumed. The market for hashish to this day is still more popular in Europe, North Africa, and Central Asia. The best indicas have a relaxing “social high” and full-body calming effect, which allows the user to sense and feel the environment without analyzing the experience.

Kush varieties are indicas that were developed in the Hindu Kush valley, which stretches through northern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. They are a variant of indicas and have many of the same characteristics. Kush varieties tend to develop extra-wide leaf blades; however, the difference between Kush varieties and other indicas is one of nuance, rather than distinct difference.

Sativa

Sativas are found throughout much of the world, but are most famous for the varieties found in the tropics/subtropics. Potent varieties such as Colombian, Panamanian, Mexican, Nigerian, Congolese, Indian, and Thai are found in equatorial and subequatorial zones. These plants usually require a long time to mature, due to their having been naturalized and evolved in climates with longer, more consistent growing seasons. They are famous for their THC potency and resulting high. The highs they produce are described in such terms as psychedelic, dreamy, spacey, energizing, and creative. The buds usually smell sweet, fruity, or tangy, and the smoke is smooth, sometimes deceptively so.

100% Sativa Dr. Grinspoon by Barney’s Farm

Sativa plants grow in a conical, Christmas-tree form. The leaves have long, narrow serrated blades, wide spacing between branches, and vigorous growth. They often grow very tall outdoors and are difficult to control indoors. Sativas tend to grow more vertically, while indicas exhibit more horizontal growth.

Sativas have long, medium-thick buds when grown in high-light conditions found under full equatorial sun. Under lower light conditions, in temperate climates with lower light intensity and shorter days, or with indoor grows under inadequate artificial lighting, sativa stems are prone to elongating at a faster rate than indicas. This stem elongation causes “larfy” (wispy, fluffy, or airy) buds to form along the stems. The buds run, or are thinner and longer and don’t fill out completely, since the plant has stretched between the bud sites. In areas with short growing seasons, the sativa buds may not fully mature before first frost.

Ruderalis

Ruderalis is a wild or feral variety of autoflowering cannabis native to the Caucasus mountains in Russia. Unlike indicas and sativas, ruderalis is not a photoperiodic plant. A few weeks after the seeds germinate, the plants begin to produce flowers while continuing to grow. They tend to be short, between one and three feet (30-90 cm), and varieties differ in flowering growth. Unfortunately, ruderalis is a less resinous plant than either indica or sativa, producing significantly less cannabinoid and terpene content.

Nevil Schoenmaker’s The Seed Bank, which later merged into Sensi Seeds, tried using a Romanian variety that grew flowers along its new growth in an indeterminate pattern. In the early summer, the flowers were apparent, but they didn’t develop into colas with significant density. In the fall, the plants continued to grow and formed small buds, but the flowers didn’t produce heavy glandular development as they matured. Some varieties that are available commercially are more determinate. They produce flowers as the plants grow larger, and when a critical time period occurs, they quickly stop growing vegetatively and form a denser, more desirable bud.

Ruderalis Skywalker OG Auto by Barney’s Farm

Ruderalis is primarily seen as a way to introduce automatic flowering and genetics that lead to a more compact plant into indica and sativa varieties. Since ruderalis in nature is not as resinous and does not heavily produce flowers, most breeders do not see ruderalis as a valid source of genetics for crop yields or cannabinoid potency. However, developing a new variety with all the floral characteristics of a potent sativa that is shorter and matures sooner is highly desirable. Most cannabis varieties with ruderalis genetics in them are autoflowering versions of their sativa or indica cousins.

Hybrids

If indica and sativa varieties are considered opposite ends of a spectrum, most cannabis plants today fall somewhere in the middle. Because of cannabis’s long symbiotic relationship with humans, whether for potent flowers or strong fibers, seeds have constantly been procured or traded across borders so that virtually all existing plant populations have been hybridized with foreign varieties at one time or another. Since the 1980s, seeds from the Dutch and other seed companies have been introduced in traditional cannabis-growing areas all over the world including Colombia, Mexico, Jamaica, and Thailand. For the most part, the only true landraces existing today are in the hands of collectors.

After 50 years of dedicated prohibition breeding, the cannabis plant has been substantially changed. Breeders began with landraces and then widened the selection. Now thousands of varieties are available from countries all over the world. Hybrids, hybrids of hybrids, stabilized crosses, and remarkable “cuttings-only” varieties propagated only by cloning are all widely available (See Appendix A: Cloning).

50% Sativa 50% Indica Hybrid Ed Rosenthal Super Bud by Sensi Seeds

Hybrid varieties are, simply put, hybridized versions of their indica and sativa ancestors. Indicas and sativas by themselves are described in their unique growing patterns and the types of high they induce. Hybrids tend to be defined more by their associated types of high. For example, the popular variety Blue Dream is a sativa-dominant hybrid. Blue Dream does not necessarily grow the way archetypal sativas do; however, it does induce the typical full-body calming effects from its Blueberry indica heritage in tandem with a more robust, invigorating cerebral effect from its Haze ancestry. Thus, Blue Dream is a sativa-leaning/dominant hybrid variety.

What About Hemp?

The biggest difference between “hemp” and “cannabis” is the name, although that is a gross oversimplification. The word is adapted from the proto-Germanic word “hanapiz,” which was likely derived from the Greek word “kánnabis.” The Old English version of “hanapiz” evolved into “henep,” which later became “hemp.”

Fiber hemp field, Heilongjiang, China, June 2019. Photo: Chris Conrad, TheLeafOnline.com

Hemp is a group of varieties of cannabis that were selected for their fibers and nutritious seeds rather than their medicinal flowers. Hemp fibers have been farmed in China for at least 6,000 years. The Ch’i Min Yao Shu is an agricultural encyclopedia written by Jia Sixie in the 6th century CE. The title translates to “Essential Ways for Living of the Common People.” Jia Sixie was an agronomist and wrote this book to describe important crops in China. Hemp is the only plant mentioned for its fiber quality in the book.

Hemp cultivation in Europe may have started as early as 3,500 years ago and, once again, was primarily used for its fiber content. Researchers see ample evidence of its cultivation in places like Turkey, around 700 BCE. Hemp fabric was found in a Phrygian Kingdom gravesite, near modern-day Ankara.

Ancient breeders selected for cannabis plants with longer stalks to get longer fibers. Eventually those cannabis plants’ morphologies became what is seen in hemp plants today: long, singular stalks.

Hemp seed consumption is also an important part of hemp’s history with humans. Hemp plants provided nutrition to Paleolithic humans but was cultivated for food in China through the Han Dynasty. Hemp seeds are an easily digestible source of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and essential proteins. The seeds can be pressed to create hemp oil, or they can be eaten raw straight from the plant. In some areas of present-day China, farmers will make a porridge of milled hemp seeds. Pressed hemp seeds were more than just a food source; the oil was also used as a fuel source for burning in lamps during ancient times.

There are many uses for hemp fibers and oils, which continue to expand in modern times. Just like indica, sativa, and all the hybridized cannabis varieties were and continue to be bred; however, they were bred for their effects more than anything else. Hemp varieties were and continue to be bred for their fiber and food properties. Modern hemp and cannabis varieties all started from ancient cannabis plants that early humans came across growing in the wild. Those prehistoric humans cultivated and bred the plants to reflect traits that people desired. Modern-day hemp is being used for raw materials such as fiber and food, but new end uses are being developed all the time.

Cannabis has a tremendous number of possible uses. From feeding the stomach to feeding the mind to feeding livestock to creating eco-friendly building materials and plastics that don’t last in nature indefinitely, the future of cannabis is robust; however, that future was greatly influenced by cannabis’ past interactions with humans as they migrated across the globe with hemp seeds in tow.

Above: hemp house constructed by Hempitecture. Photo: Courtesy of Hempitecture

Inset: close-up of hempcrete brick by Hempitecture. Photo: Sofia DeWolfe