FEATURED GARDENS & GROWING STYLES

Dennis Peron’s Revolutionary Balcony Garden

by Ed Rosenthal

In 1969 Dennis Peron disembarked from a troop carrier from Vietnam to San Francisco. He decided to stay, found housing, and opened his duffel bag to start dealing the kilo of Southeast Asian cannabis he brought with him. From those beginnings, Peron became the founder of the first medical cannabis dispensary in the United States, offering a revolutionary model of compassionate care that included providing free cannabis to those who could not afford it. He was a leader in the cannabis reform movement, and he also was a friend of mine. Dennis died on January 27, 2018. His loss is felt greatly, and this edition of the Cannabis Grower’s Handbook is dedicated in his memory.

Dennis was one of the first medical cannabis activists in the United States. The medical community and cannabis industry worldwide owe a debt of eternal gratitude to Dennis, who saw the unfairness of making sick people endure pain when there was medicine to relieve their suffering, and who did something about it.

Originally from the Bronx, Dennis grew up in Long Island and served in the US Air Force during the Viet Cong’s Tet Offensive in 1968. Dennis chose to move to San Francisco because of the freedom he found there. At that time, homosexuality was widely discriminated against all over the country, and San Francisco had a large gay population that has had a profound effect on the area’s attitudes, politics, and culture.

Within a few years he opened a café, The Island, downstairs from his cannabis shop, located on the second floor. The Island had a cozy atmosphere, and cannabis use was policy. In 1973, I signed the contract for my first book, Marijuana Grower’s Guide, on the premises.

In 1978, Dennis wrote San Francisco’s Proposition W, gathered signatures to get it on the ballot, and 63% of the voters agreed, approving the demand for a ceasefire in the war on cannabis and making San Francisco the first city in the nation with a “lowest priority” enforcement law. It read, “We the people of San Francisco demand the chief of police and the district attorney stop the arrest and prosecution of people for possessing, transferring, or growing marijuana.”

Harvey Milk, the first openly-gay elected official in California, was a good friend to Dennis. He started his political career collecting signatures for the initiative. He would continue as a San Francisco supervisor before he was shot dead by another supervisor who was a crazed right-wing, antigay terrorist.

In 1993, Dennis’s life partner, Jonathan West, died of AIDS. Dennis had seen the relief that cannabis provided Jonathan as the virus ravaged his body. It helped with the nausea, the anorexia, and the pain in his joints and nerves.

After seeing how much cannabis had helped Jonathon as he was dying, Dennis opened the first medical dispensary in the United States, the Cannabis Buyers Club. It was located on Church Street in the heart of the Castro District, the most ostentatiously gay area of the city.

Dennis knew he was taking a risk, but the establishment was an immediate success, and within a few months over 5,000 medical patients had joined the club. Dennis was considered an angel by many of the patients he served, providing respite and comfort to the sick and needy.

Not only did the Cannabis Buyers Club provide patients with cannabis, it also served as a community center and living room for many of the patients who lived in SROs and had lost their jobs, and often their friends, when they became ill.

Tom Ammiano, then on the San Francisco Board of Education, cut the ribbon at the opening of Dennis’s club. He went on to become a California assembly member and remained an advocate of legalizing cannabis.

In 1996, Dennis coauthored Proposition 215, California’s medical cannabis initiative that, for the first time in the nation, allowed patients with a written recommendation from their doctor to possess and grow cannabis.

Clients socializing at The Cannabis Buyers Club, San Francisco, California, 1994

The Cannabis Buyers Club was closed in 1996 by then California attorney general Dan Lundgren. Lundgren was another ultra-right-wing zealot; however, the dam had broken, and dozens of new medical dispensaries were opened by former workers who were trained at Dennis’s dispensary. Now, there are tens of thousands of dispensaries in countries all over the world.

Dennis never reopened his dispensary. He was more of a social worker and social innovator and just didn’t have the ambition to be a merchant.

He lived in the Castro District of San Francisco in the house that came to be known as the Castro Castle. He converted the space to an oasis of greenery, comfort, and hospitality.

Dennis was always a big supporter of homegrown cannabis and of letting patients grow their own medicine.

One would think that Dennis would depend on the largesse of medical dispensaries and growers for his medicine, but that wasn’t the case. He grew his own.

Dennis’s garden was one of my favorite gardens to visit even though it was not the most efficient or productive. I enjoyed it because of the diversity of the plants. Dennis would often get clones from friends, and he chose to grow small plants in a constant rotation.

Dennis started his clones in rockwool in a small room to the side of the house. Once they got large enough, he transplanted them into containers that range in size from about 1.5 gallons to 5 gallons (6-20 l).

He liked to grow in containers that could be moved around so that he could manipulate their flowering cycle by moving them into darkness, and also because they were easy to move into sunny areas of the deck. The sun’s angle, and thus the sunny areas, changed with the season and the time of day.

When I visited Dennis in 1994, the plants were basking in the early afternoon sun. One group was on a specially constructed shelf along the deck fence and another group was sitting on a table on a sunny deck.

Each evening he placed his plants in a small room or in an outdoor shelter covered with opaque plastic to protect against both stray light and the cold night air of San Francisco, which can drop from a daytime temperature in the high 70s (~25°C) down into the low 50s (~11°C) or even 40s (~6°C) at night.

All the plants were forced to flower when they were small so that they remained manageable, under two feet (2.4 m) tall. The fertilizer and soil brands varied because friends often donated material.

San Francisco is cool during the summer because the cold air from the sea meets the warm inland air there, creating fog. The winds change around Labor Day, which means that the sun can penetrate. September is the warmest month of the year in the city, with warm, clear weather. The cool summer weather delays growth and maturity, so varieties take 20-30% longer to grow and mature there.

The cool weather does have its advantages. The mild conditions make it much less likely to suffer environmental damage. There are few problems with insects. Also, the plants don’t suffer from container burn (containers getting hot from strong sunlight and harming roots), and their water needs are much lower than plants growing in hot conditions.

Dennis Peron Garden, San Francisco, California, 1994.

When I visited, Dennis’s plants were in all stages of growth, from close to harvest to clones growing into young plants, attributable to San Francisco’s mild climate.

Throughout the year the daytime temperature rarely dips below 40°F (4.5°C), and even in winter the temperature can rise into the mid-70s F (mid-20s C). Plants can be grown year round, especially in this situation, where plants get sunlight during the day and protection from the cold air at night.

In late September, plants would start flowering immediately unless they were given supplemental light to break up the long dark period. Then, once they were tall enough, they were moved outside to flower under the long night regimen of uninterrupted darkness.

Dennis’s garden was not only full of healthy plants; it was rich with historical meaning and a small reflection of Dennis’s significance in the fight to end marijuana prohibition.

I miss him.

KISS Garden (Keep It Simple System)

By Dan Vinkovetsky, formerly Danny Danko of High Times

If a grower is seeking an affordable and easy way to procure a pound (~0.5 kg) or more of pristine cannabis flowers every three months, look no further than this uncomplicated and manageable system for less than a $1,000 initial investment.

Grow Tent

Get a light-tight unit that’s easy for one person to set up and take down. Choose a tent sized appropriately for the available space. This one is a 5 x 3 x 6.7 feet (1.5 x 0.9 x 2 m) UltraGrow tent unit, but there are plenty of similar options available. Make sure it comes with sturdy metal supports for the lighting and has holes for intake and outtake fans as well as flood protection. Many tents come as grow kits with lighting and fans included, but it is not necessary to pay extra for a complicated hydroponic system when it is far more simple to just hand-water the plants in containers. Once the tent is set up, go inside it with the door closed and the lights off to check for any possible light leaking in from outside.

Buckets

I recommend the cheap 5 gallon (19 l) buckets that are readily available. Be sure to drill holes in the bottom for drainage and use trays underneath them to contain overflow. Never allow plants to sit in stagnant water. Remove any overflow to prevent complications. Buy a 1-2 gallon (3.75-7.5 l) watering can and a spray bottle from the hardware store. Start with 1 gallon (~4 l) containers, which are about 8 inches (20 cm) in diameter at the top, and transplant into the 5 gallon (~29 l) containers before the flowering stage.

Soilless Mix

I fill the buckets with a soilless mix that already contains coco coir or mini-sized LECA and other amendments. I recommend Pro-Mix BX as a base and then add dry supplements. These include additional perlite, bat, or seabird guanos, greensand, beneficial microbes, bacteria, and more. I use a quarter to a half cup (34-68 g) of each supplement per 5 gallon (19 l) bucket. Different supplements are concentrated at different levels, so this is just a basic guideline. The important thing is that it’s light and airy.

Lighting

I try not to overwhelm myself with too much light for the space. The one in this tent is a 1000-watt Plantmax high pressure sodium lamp driven by a Quantum Blitz digital ballast. The six inch (15 cm) reflector by Sun System spreads all available light efficiently to the canopy below. The light raises the temperature dramatically, so I have to set up an air conditioner in the room outside the tent and use a strong window fan to exhaust the air. Next time, I’ll install an efficient LED lighting system. It uses much less electricity and produces much less heat.

Nutrients

The plant food that the grower chooses will determine how often to fertilize and how much to add to the nutrient solution. I love the line from Suite Leaf because it’s clean, straightforward, and almost 100% vegan. Whatever feeding system is chosen, be sure to feed lightly at first and bump up the nutrients as the plants grow larger.

Fans & Filters

It’s important to move cool fresh air in and hot spent air out at the proper rates, so be sure to use an outtake fan that can clear out the tent in less than five minutes. The one for this tent is rated at 435 cfm. It’s attached to a six inch (15 cm) in-line duct fan by Grow1 attached to a six inch DL light-proof ducting exiting the tent. The intake fan uses an eight inch (20 cm) UltraGrow light-proof ducting inside the tent. Always keep at least one oscillating fan inside the tent to move air around as well. Ours is a Monkey Fan from Secret Jardin.

Monitors

There are a few items it would be foolish to do without. A digital thermometer with a built-in hygrometer keeps track of the temperature and humidity inside the tent, even when I am not there.

I use the Wireless Weather Station by Grow1 unit. It alerts me the moment that the tent environment strays from preset limits. I also measure the pH of the nutrient solution after I’ve mixed in the plant food before watering. The inexpensive chemical test kits for aquarium water provide a rough idea of pH, but there are inexpensive electronic meters that indicate more precisely. A timer keeps the light schedule whether I’m home or not.

CO2 Supplementation

I use different cheap and effective ways to increase carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and thus plant yields. I’ve used mushroom buckets and CO2 production bags. These units produce CO2 gas as a result of natural biological processes. They continue producing gas for the entire 65 days of the flowering stage. In this tent, I used Green Pad CO2 generators that are doped cloth pads activated by simply hanging them up and occasionally misting with water.

Harvesting Materials

I use a clean table and a comfortable chair in a cool room with decent lighting for proper trimming. I also use a magnifying glass to closely examine the flowers to determine ripeness. For trimming, I use small clipping scissors or snips, rubbing alcohol (for cleaning scissors), string or coat hangers for drying branches to hang from, and a fan to move the air around in the drying area (not pointed directly at drying branches). Finally, I use glass jars for curing and storing buds.

Other Useful Items

I use a step stool to sit on while I’m working in the tent, a notebook pad and pen to keep track of everything, and a calendar to keep track of and dial in the timing of every grow. Once my tent is set up and my plants are growing, I hand-water them as needed, alternating between using nutrient solution and plain water. Once they have three or more sets of leaves, it’s time to start training them in order to increase their yields. In this tent, I’m using the Screen of Green system (ScrOG), Trellis Netting from Grow1.

I also employ strategic defoliation of some fan leaves and lower branches during the vegetative stage to stimulate growth and aid in the circulation of air below the canopy. This keeps fresh air moving throughout the tent and helps avoid mildew, mold, and bud rot from stagnant air pockets.

I lower the light to the proper distance from the canopy level and raise the light as the plants grow taller. This keeps them from stretching for the light and growing long and lanky instead of short and stocky.

Danny is the author of Cannabis: A Beginner’s Guide to Growing Marijuana, host of the Grow Bud Yourself podcast, and editor at Northeast Leaf Magazine.

Danny uses Suite Bloom nutrients and Ed Rosenthal’s Zero Tolerance to prevent and manage pests. Photo: Dan Vinkovetsky

Big Floating Buds: Tyler’s Aquaponic Garden

By Felisa Rogers

“I’m in the room. You wanna see the girls?” asks Tyler Leblanc. He’s standing above a uniform forest of giant buds. Each plant consists of one stem that’s grown up into a spiral. The tightly packed flower is the shape of the club a cartoon caveman might carry. “See how it just grows one bud straight up?” he asks. “These buds gotta be about 30 grams.” To demonstrate the size of the clusters, Tyler holds up a wine bottle, which is dwarfed by the cola. “They’re just rock hard,” he says happily.

The key feature of this unusual garden is difficult to see at first. But the two foot (60 cm) tall plants are floating in a single pond, stabilized by styrofoam rafts. Tyler says it’s possible to grow between two and four plants per square foot (0.09 m2). By putting small plants immediately into flower, he saves a month’s worth of energy.

The obsession with growing giant plants was of course spawned by maximum plant counts for medical grows, but giant plants aren’t energy efficient. “You only harvest the top foot or two [30-60 cm] of the plant, right?” Tyler points out. “With these tiny plants, you save a month of vegging, and the pruning, the labor, everything is less because it just grows so quickly,” he explains. “Even trimming—it’s just one big rock solid bud. The dream, right? You can just push these floats down the pond like they do with lettuce and that’s your automation.”

This floating garden of dwarf plants was inspired by Ed Rosenthal’s theories on best practices for minimizing labor and maximizing energy efficiency. The arrangement is a fraction of the hassle of a traditional hydroponic grow. Filling the pond with water requires little effort, and the waterway makes it easy to move the plants around. There’s no hauling of buckets, no solid grow media, and no drip lines. By simplifying the process, he’s created a method with fewer potential breaking points.

This is only Tyler’s second time growing using this technique. Once he tweaks it a bit, he envisions a larger operation. “The idea of using this on a commercial scale is that it is easily automated so we wouldn’t touch anything and the plants would just float down the pond while growing into massive buds.”

For now the pond is only nine by four feet (2.7 x 1.2 m). Four floats measuring two by four feet (0.6 x 1.2 m) are home to 108 plants. To prevent algae growth and protect the roots from light, Tyler uses garbage bags to cover the narrow channels between the edge of the floats and the side of the pond. This floating forest requires minimal intervention. In fact, Tyler says that it can go unattended for a week at a time.

The garden requires no unusual strategies for lighting, water, or nutrients. The water is from the well. Tyler uses an $18 Venturi adapter meant for a dishwasher hooked in-line for the water chiller output in addition to an air pump with tubing to 10 air stones that he places around the pond.

The lights are high pressure sodium. Tyler feeds the plants every day with a diet of Current Culture nutrients: Veg A&B, Cal Roots, and UC Roots, an optimization and sterilization agent. He thinks that UC Roots is a vital component to his success.

It might be possible to use a little rooting gel and put the clones directly into the raft, but this time around Tyler started out with aeroponic cloners. “When they get a nice white root, I take them out of that and put them in the pond,” he says. Using this method, he cuts out the vegetative stage almost entirely. Once they are planted, he keeps indica-looking plants in vegetative growth for 3 to 10 days, but starts forcing the sativas to flower immediately.

The pond garden is an experiment using two cultivars. The Moby Dick looks a little leggy, but the OG Mendo Grape is stout and sturdy. Indicas are likely the better choice for this style of growing because they stay fairly short and stout. Tyler occasionally had to prune to prevent branching, but if the plants had been placed a bit closer to each other, it is possible to create an even canopy that would naturally stop a tendency toward branching. “With the right cultivar you can leave it untouched and it’d grow straight up,” Tyler says.

Like any garden, there have been some problems to solve. Tyler relies on help from his uncle, a talented local gardener. “I couldn’t have implemented this without the dedicated support of Uncle Ribinski,” Tyler says.

Originally he started the water at a pH of 5.8. “The plants had explosive root growth but the tops shriveled and died,” he says. He upped the pH to 6.2 and got happy plants. At another point in the grow, he realized that the roots were getting too much CO2 from the air pump. He moved the pump out of the grow room so that it wasn’t sucking air enriched with CO2. The problem disappeared.

Calibrating water temperature and pH is essential to this style of growing. Both need to drop as the plants grow. “When you put them in the water it should be between 70 and 72°F (21 and 22°C). The target pH until they acclimate should be 6.2,” he says. “As soon as it takes and you get a little new growth you can drop the water to 70°F (21°C) and the pH to 6.1,” he instructs. “Once you trigger flowering, you drop the temperature to 68°F (20°C) and the pH to 6 and keep it that way for two weeks. By the third week, the pH is reduced to 5.9, while keeping the water at 68°F (20°C). Maintain for three weeks. For the last three weeks of the flower cycle, the pH should be 5.8.

The current crop was in flower for 56 days. He estimates that the typical cycle for this type of garden is about seven or eight weeks, maybe a little more for some cultivars. He expected about 30 grams per plant, though the plants yielded a fraction more, averaging 31 or more. His biggest plant from the grow yielded 42.5 grams. “It was one bud, straight up!” he says, adding that the flowers were aromatic, covered in trichomes. “Smokes smooth and hits hard,” he says with a smile. The total yield was 3,240 grams, or 7.1 pounds (3.24 kg).

Processing is simple. He just picks off the bigger leaves and hangs the entire plants, using traditional good practices for curing. There are no larfy branches, so the final product requires very little trimming. Starting over is also simple and waste free; he just drains and refills the pond and reuses the rafts. He estimates he can do five or six gardens a year.

Clones are installed to float over the reservoir. Photo: Courtesy of Tyler LeBlanc

Plants grown in this aquaponics system grow long, dense colas. Photo: Courtesy of Tyler LeBlanc

Oklahoma Sungrown: Localized Breeding with Fungi & Hügelkultur

In 2018 Oklahoma voters passed State Question 788, which legalized medical cannabis use and possession, solidified the right of patients to maintain home gardens, and created a free market for commercial cultivation with low barriers to entry. The result has been a robust industry full of locally owned and operated businesses that thrives off constant innovation and community breeding.

Friends and farmers Jeremy Babbit and Andy Unruh are both licensed growers under the Oklahoma Medical Marijuana Authority (OMMA) and work together to explore and improve on permaculture practices adapted to the unique microclimates they live and garden in. Through a combination of regenerative agriculture techniques, including hügelkultur, and cultivating several strains of carbon-dioxide-producing mushrooms, they are producing localized varieties of high-quality sungrown flowers for premium single-source ice hash rosin.

Hügelkultur translated from German means “hill culture.” It refers to a method of permaculture that involves burying wood in mounds or raised beds. As the wood rots, it becomes a sponge that retains moisture, thus reducing or eliminating the need for irrigation. While compost is typically broken down by bacteria, wood is digested by fungi. The use of both the rotting wood and compost creates a thriving living soil ecosystem filled with earthworms that reduces or eliminates the need for fertilizers.

Andy says that he decided to use hügelkultur because the soil on his farm was really compacted and full of clay. He had cut down oak trees six months prior, and the logs and sticks were in varying states of decay. He created a circular pattern around a post hole to create mounds as well as a traditional hügelkultur trench.

Andy and Jeremy have combined the use of the wood with helpful fungi that thrive in it as it rots: mushrooms. While some of the mushrooms grown in the gardens arrived on their own, others have been brought in by adding spores to compost tea to encourage the soil diversity and provide an ongoing source of carbon dioxide directly underneath the cannabis plants.

Andy says the wild mushroom strains in his garden include bird’s nest, ink head, puff balls, and rose guild mushrooms, which seem to thrive in the iron-rich native “red dirt” soil in his garden that Oklahoma is famous for. As he forages in the woods around his farm, he picks mushrooms and places the fresh caps in the compost tea he feeds the plants.

“By placing the spores, caps, and mycelium into the compost tea before feeding, I am able to introduce local native fungi directly to my plants. My best results so far have been with Stubble Rosegill (Volvopluteus gloiocephalus) and Bird’s Nest Fungi (Nidulariaceae). I have begun introducing porcini (Boletus Edulis) mushrooms, which form mycorrhizal partnerships with plants, but I have not seen any fruiting bodies to date.”

To encourage the growth of bolete mushrooms near the cannabis plants’ roots, he has thrown spores into the compost heap.

“I knew I had to get my soil mixed with more fungi because it is clay, dense, and anaerobic, and I want it to become aerobic. Fungi is one of the ways to loosen up the soil without tilling. The hyphae build pathways for oxygen, develop soil structure, decompose organic matter, and extract and hold nutrients,” Andy says.

Andy warns that not all the mushrooms are edible, and many are dangerous if consumed, but his work with the fungus has inspired him to cultivate beneficial mushrooms that are also edible, such as reishis and shiitakes, which he plans to add to the hügelkultur beds under his cannabis plants by first inoculating the logs with the spore plugs and then burying them in the beds.

Together Andy and Jeremy focus on permaculture methods and localized breeding programs with two end goals: creating thriving sungrown varieties acclimatized to the microclimates of eastern Oklahoma, and especially those that produce high-quality resin-rich flowers for Jeremy to process into single-sourced ice water hash, for both their farms as well as others using similar methods.

“I need the right resin, the right trichome heads. That is what I am growing for,” Jeremy says. Unlike Andy’s farm, Jeremy’s property doesn’t have the famous “red dirt” Oklahoma is known for, but instead clay and sandstone. Jeremy uses traditional hügelkultur beds amended with compost, coco coir, worm castings, and spore-rich wood chips produced from trees cut down on his own property.

Andy’s and Jeremy’s farms are about an hour away from each other in the greater Tulsa area. Jeremy’s farm, 918 Oklahoma Grown, is just northeast of the city in Collinsville; Andy’s is Sticky Flower Farm, to the southwest outside Depew. They are quick to point out that the State of Oklahoma has many diverse microclimates, from the wetter and greener rolling hills in the east to the dry, arid land in the western panhandle sandwiched between Texas to the south and Kansas and Colorado to the north.

Andy Unruh next to the beginnings of a hügelkultur mound. Photo: Jeff Hooten

While the goal of Jeremy’s garden is to produce high-quality solventless concentrates with locally bred varieties, Andy says the goal of his garden is to work with farmers and breeders throughout the state to create a community around producing genetics specialized to the region.

“The community here in Oklahoma is really good, State Question 788 has given everyone the opportunity that wants to put in the effort, do it legit, do it right, and not put out a half-assed product,” says Jeremy. “I want to find genetics that grow well outdoors and produce the best hash rosin I can make.”

Most commercial cannabis varieties available in Oklahoma and other states in the East, Midwest, and South were the result of breeding programs and alliances that originated on the West Coast. While most states east of the Rockies have strictly limited the amount of grow licenses and the qualifications to grow, Oklahoma’s free market approach has resulted in thousands of small farmers like Andy and Jeremy, with the ability to breed and grow new plants that are more appropriate to the region.

Andy says, “Oklahoma is absolutely incredible for having a local breeder community. If we work together as a community on cultivars and methods that work best in our state, we will find cultivars that Californians wish they could grow as well as we do, just like we wished we could grow specific cultivars as well as they do.”

Neither Jeremy or Andy refers to himself as a “master grower,” but as farmers. Both seek to transform the region’s current farming practices and have integrated permaculture and regenerative techniques into their gardens.

“I am just a farmer. I don’t know anyone on my dad or mom’s side of the family who wasn’t a farmer. I am just going back to my roots. I saw too many people using ‘traditional’ commercial agriculture practices but always struggling and always fighting something,” Andy says about the decision to transition to using natural techniques.

Both farms produce one yearly annual harvest under natural light. Although neither plans to use light deprivation, they have gotten creative with planting seasons and using autoflower varieties.

Jeremy’s garden is 40 by 72 feet (12 by 22 m) and enclosed in a state-mandated 8 foot (2.5 m) fence. It contains 100 plants of 12 varieties. He is growing some for the first time and others that are reliable hash plants. He started some from seeds and others from clones obtained from local breeders. He has a preference for sativa varieties but tends to grow more hybrid and indica-dominant plants because they are better hash producers, as are most Diesel varieties. Currently he’s growing Killer Cupcakes, Sundae Supreme, Watermelon Zum Zum, Glue Ball, Thunder Diesel, Durban Kush, Orange Mac, MorningWood, Strawberry Diesel, Cornbread, and Island Mimosa.

Andy’s garden is smaller than Jeremy’s and includes a personal home garden where Andy does most of the breeding and experimentation. Unlike Jeremy’s, Andy’s is a seed garden. Its purpose is breeding and storing local-specific varieties.

He has propagated feminized seeds from Morning Wood, a cross of Sour Diesel and Alaskan Thunderfuck produced by local breeder Pac-a-Punch. Both he and Jeremy say it produces great hash. Morning Wood was crossed with Green Crack, which will eventually be released as “Pepe Depew.” Local breeder Oklahoma Kush Collective has provided an Athena’s Wisdom that he is experimenting with. He has crossed two of these plants with Thunder Cheese from another local breeder, Shaggy Roots, which was crossed with Purple Urkle. There is also a cross of Green Crack and Purple Urkle and a new unique variety from out west: Freak Show, which looks more like a fern than a traditional cannabis plant.

Jeremy Babbit’s outdoor farm contains 100 plants of 12 different varieties. Photo: Jeremy Babbit

Jeremy must contend with all four seasons. It gets hot and humid in the summers. He irrigates the plants with just enough water to keep them from wilting. They are supported using netting and cages when the plants grow large. Beyond the heat, the biggest challenge is dealing with grasshoppers and caterpillars, which like to burrow into nugs and destroy them from the inside.

Andy’s farm is a lot wetter, so he breeds for mold resistance and, when necessary, uses an indigenous microorganism (IMO) spray to keep mold at bay.

Andy’s gardens are irrigated using a drip system. Jeremy uses several methods, including soaker hoses and gravity beds.

Both farmers seek natural methods of pest and fungal control. Jeremy has attempted to rely on his turkeys and guineas to eat up grasshoppers and caterpillars, but they haven’t been too reliable. Both use natural foliar sprays to control pests and fungus including Dr. Zymes and IMOs. Both gardens are abundant with beneficial predators including ladybugs, praying mantis, assassin bugs, and spiders.

When it is time to harvest, Jeremy is focused on preserving the high-quality trichomes that he will make into hash. He takes the plants into a freezer room immediately after harvest, chops off the nugs and prepares them to become ice water hash.

Both use traditional drying and curing methods to harvest flowers: hanging the branches to dry in a temperature- and humidity-controlled space before burping in jars as they cure.

Mushrooms are encouraged to grow in the dirt as both a source of CO2 and below-the-surface fungal life. Photo: Andy Unruh

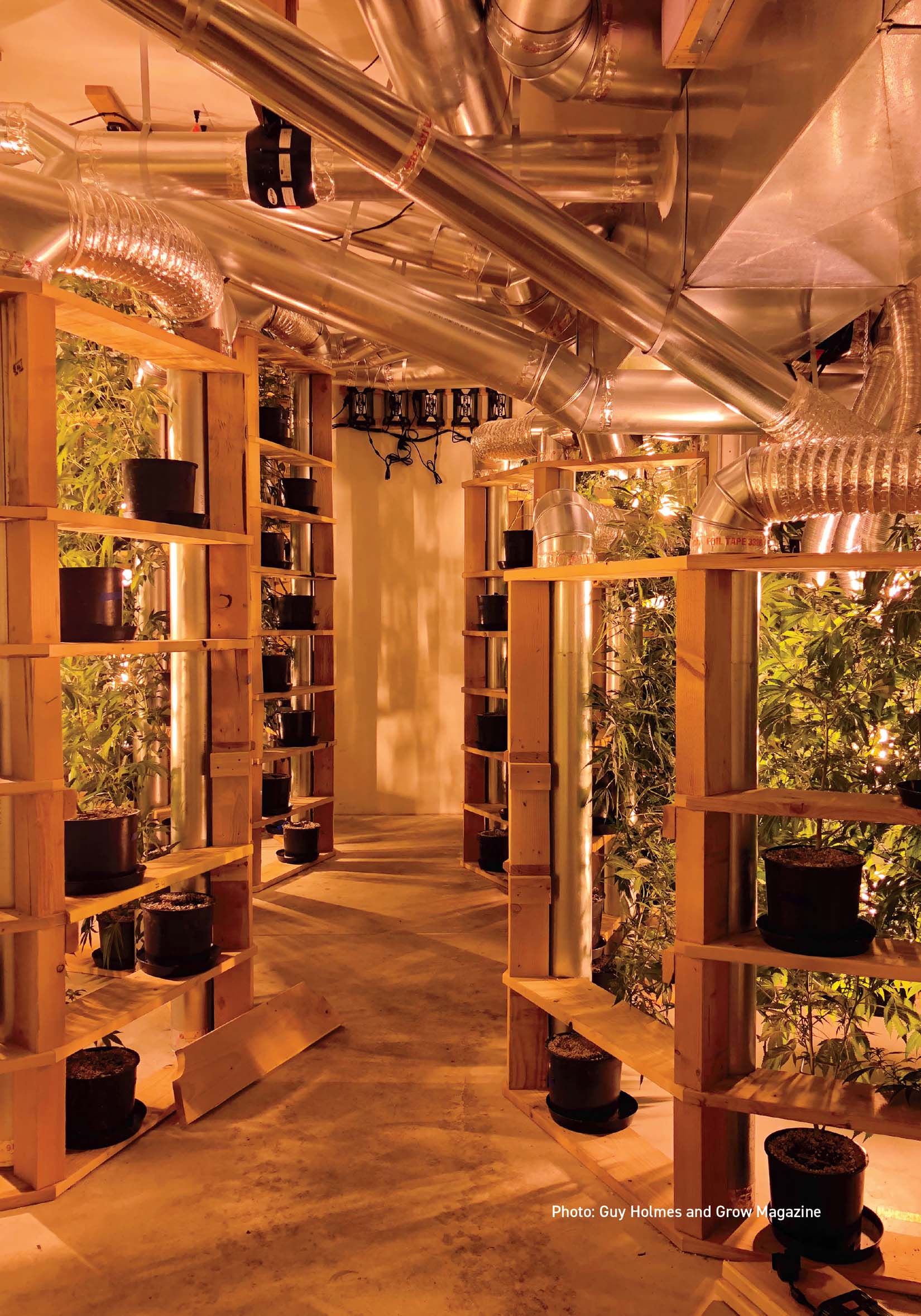

Creswell Oreganics Octagon Gardens

Growing vertically has several advantages, but the reason why this grow method is so efficient is it maximizes all the energy produced by the HPS lamp and minimizes the space and power needed for rooms dedicated to vegetative growth. Rather than lighting a horizontal garden with overhead lights and reflectors, the canopy is literally wrapped around the bulb, absorbing all the output produced by the lamp and doubling the canopy space that the lights are covering.

Trent Hancock of Creswell Oreganics designed two “octagons” for vegetative growth and flowering. The octagon for vegetative growth has six shelves evenly spaced, with three containers per shelf. It is capable of holding 128 plants and supplying four flowering octagons.

The flowering octagon is 12 feet (3.65 m) in diameter and has eight sides with four levels of shelves that each hold two plants around four vertical HPS lights. Each level is spaced evenly, with the top shelf at 6 feet (15.25 cm). Each shelf holds two containers.

As the plants grow up and out toward the lights at a 45° angle, they cover the containers on the shelf above them. The flowering octagon holds 64 plants that produce up to four ounces (113 g) of flower each. Although the plants stay relatively small, between 3 and 3.5 feet (0.9-1 m), the yield is higher and the density is spread throughout the entire stalk, not just the top cola.

The goal of Creswell Oreganics is to produce connoisseur-quality flowers in the most cost-effective and natural ways possible: to have “all the quality of indoor with the efficiency of outdoor” growing. Creswell has focused on vertical efficiency and using rapid-fresh air exchange as a method to control pests.

The air inside the octagons is rapidly exchanged. This creates a hostile climate for bugs; they are blown off by wind gusts and cannot move or reproduce in cooler climates. Hancock designed the garden so that the air could be fully replaced every 20 seconds in order to simulate a high-altitude climate that is inhospitable to pests. The gusts and warm air in the daytime prevent the proliferation of mold and mildew spores, and cool temperatures in the night cycle prevent proliferation of pests. Air is exchanged rapidly using three air plenums that interact with each other. Temperatures are kept at 75°F (24°C) during the day cycle and lowered to 48°F (9°C) during the night cycle. The heat bursts during the last five minutes of the day cycle at 94°F (35°C).

The company grows with one solid philosophy: they won’t grow it if they wouldn’t smoke it. This means dedication to pest-free climates and never using sprays of any kind, even certified organic pesticides.

Creswell produces a regular supply of cannabis flowers for dispensaries in the Portland and Eugene, Oregon areas. Trent got his start as a teenager in the 1990s working on small indoor gardens in Oregon. He relocated to Montana, where he ended up with a felony cannabis charge in 2004. While he was on probation, he studied political science and started consulting. When Montana legalized medical cannabis by ballot initiative, also in 2004, as a felon Trent was barred from being a provider in the industry but became a consultant to legal medical gardens and helped design many that reached commercial success.

Trent produced well-known cultivars in Montana including Big Sky Kush and Blueberry Silvertip. After a ruling in the Montana Supreme Court shut down legal cultivations in 2016, Trent and head grower Shayney Norick relocated back to Trent’s home state of Oregon and founded Creswell Oreganics.

Photo: Guy Holmes and Grow Magazine

Creswell usually grows about seven varieties at once. They specialize in their own cultivars, Grapefruit Crater and Crater Kush (White Widow x Obama Kush), but grow other regional favorites like Purple Punch, Kashmir Kush, and White Tahoe Cookies.

When Shayney and Trent are pheno-hunting, they start with up to 5,000 non feminized seeds and whittle them away through a series of stress tests. The 300 best structured plants with the best immune systems are cloned and numbered. They go in the flower room in a soilcoir mix. After the seedlings flower, the best three versions of the cross are saved in the clone room and the other clones destroyed. The final phenos are determined by aroma, effect when smoked, aroma after smoking, trichome production, immunity to mold and disease, structure, root structure, and speed of vegetative growth and flower ripening.

The plants are fed just enough liquid nutrients to not be deficient, customized to each variety’s preferences. Water is mixed in tanks and plants are watered by hand.

“We never have to spray, so it’s the only time we have interaction with the plants. I use it as time to check on them,” Trent says. “The best crops I ever had was when I was a small grower. Shayney and I try to do as much as we can to repeat that high quality on a commercial level.”

After harvest, plants are dried using a negative air pressure dry rack that pulls air from the center; the shelves each have their own intake drawing evenly at the edges. Once buds dry to the touch, it is sealed up and opened every day until the stems snap.

Autumn Brands: Dutch-Style Flower Farming

Courtesy of Autumn Brands

Autumn Brands provides hundreds of dispensaries in California with a variety of pesticide-free cannabis flowers and pre-rolls grown using a unique integrated pest management program and the wisdom of six generations of Dutch-style cut-flower farming.

“We don’t spray anything, not even organic pesticides,” says Hans Brand, who oversees the greenhouses with his son Johnny.

The goal at the garden is to meet market demand while also being sustainable, contaminant free, and cost efficient. To control pests, for the last three years the farm has relied on a sparkling clean facility and local beneficial insects that have moved in and made the greenhouses their breeding grounds.

As no-spray cannabis farmers, they search for and develop resistant varieties that thrive in the “sun grown indoor” climate provided in their greenhouses in Carpinteria, California. Year-round high temperatures in this coastal southwestern town range between 70-88°F (21-31°C), with 280 days of sunshine annually and 60-65% relative humidity.

Once Johnny determines that a variety is not hypersensitive to the humid climate, he tests 10 plants, observing each one’s unique growth patterns through three distinct stages. First, he observes how quickly and easily cuttings grow roots. Next, he observes how fast they grow and mature. Finally, he looks for plants that swell quickly and finish with strong and dense trichomes.

The full process takes around six months, and Johnny is constantly searching for new varieties to test and grow. The family has grown in the same greenhouses for more than 27 years, using techniques and knowledge accumulated by his father and grandfather that were passed down to him.

“Growing quality flowers is more than the right [genetics], plants, and technology. It’s a feeling for the flowers. You can’t get it from a book or from a school. It’s in your fingers … it’s in your blood,” says Hans.

The Brand family began farming flowers in Holland more than a century ago, and today Johnny carries on the family’s flower-growing tradition as a sixth-generation flower farmer, although he is the first to specialize in cannabis.

Johnny grew up in his father’s greenhouses when they were still producing tulips and gerber daisies. Like other cut-flower farmers in the region, the Brands’ business started declining in the late 1990s after Congress enacted the Andean Trade Preference Act (ATPA), which encouraged South American countries like Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador to transition coca production to cut flowers.

California flower farmers couldn’t compete, and a steady decline in the business continued through the early 2000s, with nearly half the state’s cut-flower farmers out of business by 2012. That’s when the region’s farmers increasingly started to look to producing another kind of flower.

The Brand family began that transition in 2015 under California’s medical cannabis law. At first, Hans was not a cannabis proponent and was skeptical when a cannabis grower asked to rent space in one of his greenhouses.

It didn’t take long for Hans to recognize the financial opportunity in growing cannabis flowers, and so in partnership with Johnny, daughter Hanna, and partner Autumn Shelton, who had worked with the farm when it was still producing flowers, Autumn Brands was born.

The greenhouses deliver a steady stream of pre-rolled joints and flowers to popular dispensaries in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and other parts of the state where adult-use retail sales are legal. In order to maintain the quality and product integrity, the garden was designed with the same efficiency as when it produced cut flowers.

“We have developed our systems to be lean and mean. I used to battle over pennies in the flower business, and I am taking the same approach in this business. We don’t throw around hundred dollar bills. We try to be frugal and smart and to keep the overhead low at all times,” Hans says.

Each greenhouse produces six harvests a year of a dozen “mainstay” varieties, including Chocolate Hashberry, Dream Walker, GG #4, Orange Crush, OG Kush, Purple Punch, Shark Shock, Sour Diesel, and Strawberry Banana. The Brands often experiment with other varieties as well, including CBD cultivars such as Blue Dream CBD.

Courtesy of Autumn Brands

Plants are started as clones and grown hydroponically using a coco coir medium. They are constantly watered through a closed loop system that irrigates 12 times a day with nutrient-adjusted water that is looped and blended with fresh water for the next watering.

Once plants have rooted, they are placed on rolling trays for efficiency. Each tray contains 128 plants that move together on the rollers as needed throughout the greenhouse. Two layers of trellising are placed to support the plants, once in vegetative and the second time as the plants enter flowering and the buds become heavy.

Autumn Brands does not use supplemental lighting, since it’s so sunny year-round. The greenhouses’ climate is controlled using software, but generally the overnight low in the rooms is 59°F (15°C) and daytime highs are between 80-86°F (27-30°C). Occasionally in the winter, heating is used to keep the rooms from freezing, but the biggest concern is humidity control.

Humidity is maintained in the low 80s at night using climate controllers that measure and adjust the climate based on the current dew point, relative humidity, humidity deficit, temperature, and available light.

Plants are harvested by hand and dried in a large temperature- and humidity-controlled cooler. After drying, the harvest team begins the bucking and trimming process, removing flowers from their stems by hand with extreme care. Next, plants enter the twoweek curing phase, in which they are kept at a low temperature and medium humidity level to help preserve their unique potency and ensure a smooth, flavorful toke. Then, they are placed in eco-friendly glass jars or rolled into joints.

Plants are moved around the facility using electric go-karts. Courtesy of Autumn Brands

The California Appellation of Origin Garden

by Kristin Nevedal

Geographical indications (GIs) and appellations of origin (AO) are internationally recognized intellectual property systems that offer significant opportunity to protect valuable traditions and genetic resources for peoples throughout the world.

A GI is a sign used on products that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation that is due to that origin. Appellations of origin are a special type, or subset, of a GI in that the qualitative links between product and place must be stronger than that of GIs.

In the case of an appellation of origin, the distinctive quality or characteristics of the product must result essentially or exclusively from its geographical origin. Terroir, a French term, is commonly used to describe the combination of factors including soil, climate, and sunlight that gives the product its distinctive character.

Happy Day Farms grow both commercial cannabis and vegetables according to California’s appellation program in the Bell Springs Appellation of Northern Mendocino County. Photo: Amber O’Neill at Happy-Day Farms

These standards-based regulatory systems act to codify traditional knowledge and traditional agricultural practices, as well as protect valuable genetic resources, resulting in the harmonization of respective intellectual property standards, values, and technologies between countries engaging in the trade of AO products.

How Might These Systems Be Applied to Cannabis?

Recognized by farmers as a highly adaptable plant, cannabis is heavily influenced by the environment in which it is grown. As cannabis seeds spread throughout the world, the plant was bred for different uses and adapted to a multitude of natural environments, resulting in the development of countless cultivars with distinctive variations.

There are many regions known for unique cultivars that produce high-quality inflorescence with distinctive characteristics attributed partly to the original environment where the cannabis was grown and bred. This includes geographical regions known for modern breeding such as California’s Emerald Triangle and regions of Spain, but especially the many regions in Central and Southeast Asia where the plant evolved. This includes countries such as Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Thailand, and Vietnam as well as many areas in Central and South America and the Caribbean.

Despite decades of international cannabis prohibition, the most well known of these regions established global brand-name recognition among patients, consumers, and the public. As regional recognition increased, so has the demand for cannabis products from these regions.

However, as regional fame grew and product value increased, so did the number of products branded with regional names grown or manufactured outside the named region.

Developing the World’s First GI & AO Programs for Cannabis

In 2015, nearly 20 years after the passage of the Compassionate Use Act, the California Legislature established the Medical Cannabis Regulation and Safety Act (MCRSA). MCRSA created a statewide framework to regulate medicinal cannabis and established two very important geographical indication programs for cannabis: County of Origin and Appellation of Origin. Subsequent legislation was passed in 2019 that strengthened the appellation of origin statute.

In 2020, the California Legislature passed Senate Bill 67, which expanded the County of Origin program to also include city and county of origin indications based on political boundaries. It allows cannabis and cannabis goods produced 100% within the boundaries to bear the name of the county, city, or city and county.

Additionally, and maybe even more important, Senate Bill 67 established terroir-driven baseline standards for California’s Appellation Program (CAP), which requires that for cannabis to qualify for an appellation of origin seal, it must be grown in the ground, without the use of a structure, and without the use of artificial or supplemental lighting in the flower stage.

Pathway to Establishing a Cannabis Appellation of Origin in California

To establish an appellation of origin, a group of licensed cultivators, located within the proposed appellation region, must prepare and submit a petition to the California Department of Food and Agriculture for review and approval. Consistent with appellations of origin for products such as wine, Champagne, and cheese, California’s cannabis Appellation of Origin program requires the petitioner to, among other things:

- Show evidence of historical name use;

- Describe each geographical feature affecting the cannabis produced in the geographical area of the proposed appellation of origin, including:

a. Climate information, which may include temperature, precipitation, wind, fog, solar orientation, and radiation;

b. Geological information, which may include underlying formations, landforms, and such geophysical events as earthquakes, eruptions, and major floods;

c. Soil features, which may include microbiology and soil series or phases of a soil series;

d. Physical features, which may include flat, hilly, or mountainous topography, geographical formations, bodies of water, watersheds, and irrigation resources;

e. Cultural features, which may include political boundaries associated with a history or reputation of cannabis cultivation, the distribution of a specific set of cultivation practices, and anthropogenic features; and

f. Minimum and maximum elevations.

- Provide substantial evidence that the geographical area is distinctive when compared to areas outside the proposed boundary and to other relevant areas that produce cannabis for sale in the marketplace;

- Provide an explanation of how the geographical feature is considered intrinsic to the identity or character of the area by means other than being required by local or state law, regulation, or ordinance;

- Provide a description of the quality, characteristic, or reputation of the cannabis that is essentially or exclusively caused by the geographical feature, including an explanation of how the geographical feature causes the cannabis to have that quality, characteristic, or reputation; and

- Identify at least one specific standard, practice, or cultivar requirement that acts to preserve the distinctiveness of the geographical feature and maintain its relevance to the cannabis produced within the appellation region.

Planning for and Setting up an Appellation of Origin Cultivation Site

The Cannabis Must Be Planted in the Ground.

Planting the cannabis in the ground ensures that it is produced within the appellation region and is influenced by the native soil and microbiology unique to each appellation region. Various methods of planting in the ground may be used, including tilling, or turning the native soil, sheet mulching, and mounded beds. The type of amendments, or soil additives allowed, as well as the method(s) allowed for planting in the ground, must be in accordance with any relevant standards and/or practices established by the appellation.

The Cannabis Must Be Grown without the Use of a Structure.

Cannabis produced within the appellation region must be grown in an open-air setting without the use of a greenhouse, hoop house, shade house, or other structure that might alter the natural temporal environment of the appellation region. The use of light-deprivation techniques is also prohibited, as this technique not only manipulates the temporal setting where the cannabis is produced but also alters the natural sunlight hours the plant would otherwise receive.

Producing cannabis without the use of a structure additionally prohibits the use of coverings temporarily to protect from natural conditions such as early frost, rain, and/or smoke particulate from nearby wildfires.

Cannabis Must Be Grown without the Use of Artificial or Supplemental Lighting.

While artificial or supplemental lighting may be used for supporting the growth of mother plants and for other propagation activities, artificial or supplemental lighting shall not be used once the plants are taller or wider than 18 inches (46 cm). This baseline standard ensures that the cannabis is grown utilizing natural sunlight, subjecting it to the appellation region’s natural daylight hours and sunlight intensity.

Irrigation Water and Water Sources

In addition to the terroir-driven baseline standards established for California’s Cannabis Appellation Program, the water used to irrigate the cannabis must be sourced from within the appellation region and in its source form, or otherwise “untreated.” Such water sources could include permitted surface water such as streams, creeks, rivers, and springs, or groundwater sourced from a well or aquifer, as well as rainwater captured and stored within the appellation region.

In some appellation regions, natural environmental conditions eliminate the need for irrigation altogether, allowing farmers to utilize dry-farming techniques. Rich alluvial floodplains such as the Holmes Flat area in the Eel River Valley in Northern California, where historic flood cycles have deposited layers of silt and forest mulch on the valley floor, and the water table is naturally high, are perfect for dry-farming a multitude of agricultural crops, cannabis included.

The Benefits of GI and AO Programs for Consumers

Both geographical indication and appellation of origin programs offer consumers an opportunity to verify the origin of the products they purchase and to directly support the economy of the originating community.

Appellation of origin products offer consumers additional opportunities including the ability to verify the standards by which the products were produced, as well as the unique ability to experience the taste of a place and the subtle differences between a cultivar produced in different appellation regions.

Planting by the Moon: The Martyjuana™ Garden

The Martyjuana garden goal is to provide organic sun-grown, small-batch cannabis using the natural methods used to produce the best organic foods.

Each annual crop is cultivated using biodynamic methods, although the farm is not Demeter-certified biodynamic. Planting and harvesting are done by sun and moon cycles using systems that are sustainable from start to finish and work with seasonal rhythmic flows. Martyjuana plants seeds in spring and picks the flowers around the autumn’s harvest moon.

Batches of seeds are planted at every new moon during the spring, starting in March and ending in May or June. The dates fluctuate from year to year depending on when the new moons fall in relation to the spring equinox.

The plants declare their sex around the summer solstice and mature in time to harvest on or around the full moon in September or October. Martyjuana believes these are the elements that cannot ever be exactly re-created with indoor cultivation, which mimics sunlight but not the moon phases that change nightly. Martyjuana operates under the theory that the full spectrum of effects are more diverse when grown in the full sun and under the moon and stars for the entire life cycle of the plant. There is a natural magic in allowing the seeds to start growing along with the waxing moon as well as harvesting at the full to waning moon.

Martyjuana methods have earned awards and accolades in California’s cannabis industry. Martyjuana was the winner of the 2012 Sonoma County cannabis cup for solvent-free concentrate (hash) and featured in the mainstream Sonoma Magazine. Marty Clein, Byron Kohler, and the team at Martyjuana are longtime advocates for cannabis law reform. Marty and Byron emerged from the early medical markets of Northern California in 2004 as Big B’s Martyjuana Farm, one of the first commercial medical cannabis farms to become regionally legal and regulated. Since California legalized cannabis for adult use in 2016, these traditional methods have made them a standout craft cannabis farm in the region.

The farm is located on a pristine mountaintop in Covelo, California, a remote community in the Round Valley region of Mendocino County, the heart of the Emerald Triangle. The garden is 10,000 square feet (930 m2). Finished dried buds are distributed throughout the state in branded jars. The trim is white labeled and used by other regional brands for pre-rolls, concentrates, edibles, and other extracted products.

Plants are grown in living soil in recycled redwood planter boxes and provided nutrients only through certified organic amendments. They are watered with artesian well water sourced on-site.

The integrated pest management plan precludes the use of pesticides or any sort of spray or foreign chemicals. Instead, companion planting creates an insectary of food and flowers. California poppies, roses, lavender, chrysanthemums, tomatoes, zucchini, pumpkins, squash, and other bee- and pollinator-friendly plants are grown around the cannabis garden. Beneficial predatory insects including ladybugs, praying mantis, green lacewings, and nematodes are released to combat pests like aphids and mites.

Plants are grown from seed and bred on the farm or from neighboring farms. The original Supreme, Northern Lights #4, and Super Skunk #1 seedstock was sourced through Canada’s Cannabis Culture Magazine around 2000. Over the years, Martyjuana has crossbred a variety of cultivars by trading seeds with other farmers in the community. Preferred cultivars include old school kushes and OGs as well new cultivars like Skittles, Jelly Roll, and Gelato.

Almost all the processing is done on-site. Plants are harvested branch by branch as they ripen and hung to dry and cure in the barn to make them ready for long-term preservation and storage that protects the integrity of each flower.

Photo: Martyjuana Farms

Dry Farming with Sunboldt Grown

“Dry farming is not for the faint of heart,” says Sunshine Cereceda of Sunboldt Grown Farms.

Dry-farmed plants receive no irrigation and instead pull what they need from the soil or the atmosphere. Sunshine says that she switched to dry farming cannabis and other crops because the buds and other produce have stronger, more pronounced flavors and a clean long finish. Just as important, it’s more sustainable.

At first it is nerve-wracking for a grower to watch the plants suffer the stress of being transplanted into a dry environment, but they do adapt. Many other cultivated crops are dry farmed. Dry-farmed grapes and tomatoes, in particular, are prized for their flavor, which is thought to be richer and more concentrated in the absence of water dilution. “Natural wines” or “low-intervention wines” are dry farmed in native soil and are thought to be a truer expression of terroir, the unique location where the grapes were grown, from its soils to all the elements of its microclimate. What Sunboldt produces is “low intervention cannabis.”

Sunshine was introduced to dry farming by a neighbor farmer in Shively, California, a community on the banks of Humboldt County’s Eel River. It winds through the Avenue of the Giants, a road tour through the largest and oldest redwood trees the region is known for. Many other gardeners in the community are dry farming in the rich alluvial soil. One by one, they found that dry farming produces high-quality cannabis flowers that are dense, pungent, and flavorful. Cannabis is likely to express more of that terroir when grown “naturally.”

When the soil is tilled, the roots do not need to reach down into it to get to the water, because the water actually works its way up to the roots using capillary action. At Sunshine’s farm, the native soil is clay loam that has some of the holding capacity of clay but also allows the water to drain easily.

“Plants prefer less water and fertilizer. They prefer to be on their own. The growth is better overall. Water is an addiction for the plants,” she says.

Traditionally, dry farming relies on tilling the soil to loosen it a bit for better percolation. Instead, she uses a rotary spade that mixes her cover crop into the upper four inches (10 cm) of soil. She adds some amendments: aged redwood sawdust, biochar, and soluble calcium.

The practice of dry farming is a return to ancient traditional farming methods. Native Americans have been dry farming the deserts of the Southwestern United States for thousands of years, as have other communities around the world. These practices are still used today, which include tilling the soil to aerate it and planting seeds deeper beneath the topsoil.

Sunshine observed dry-farmed crops on the Navajo Reservation when she traveled there as a child with her mother to protest the Peabody Western Coal Company from mining on Navajo land.

“As a goal for my garden I wanted spiritual healing for people, and to grow the plant to its fullest so that I can experience everything it has to offer. I want to taste the land where my bud was grown.”

Photo: Phil Emerson

Sunshine’s garden is in a coastal climate, and the ocean has a profound moderating influence on the weather, keeping the temperature in the 80s Fahrenheit (approx. 26-31°C) during the summer and experiencing few frost days in the winter. Because it never gets too hot, the plant’s metabolism is never stressed. Nights are cool and humid, with dew drop providing moisture to the dry-farmed crops.

Sunshine R&D’s new crosses and maintains a library of cuttings in a mixed-light greenhouse in her personal noncommercial garden. After harvesting the light-deprivation greenhouse in May, the plants are moved outdoors and planted in the ground. They go back to vegetative growth because of the lengthening days and are harvested in the fall.

Clones for the commercial garden are planted in a cold frame either directly in a rockwool cube or sometimes with soil in a 3 inch (7.6 cm) pot. Once the plants have rooted in the cold frame, they are planted directly into the field in the rockwool cube or from the 3 inch (7.6 cm) pots. They will be planted in waves between May and June.

The plants may be watered once, after transplanting into the soil to encourage the roots to search for water. She dips the root ball of large plants in a bucket of water to give them a good soak before putting them in a hole deep enough to bury the stem below the topsoil, closer to the moisture.

“It was initially hard to watch the plants suffer when they were first transplanted into the ground. When new growth appeared, I was confident the roots had found water beneath the soil surface. By the third week, the plants were no longer in a stress state, but one of rapid growth.”

For the most part, the rest of the gardening process is hands off, other than monitoring for pests. As part of an integrated pest management (IPM) plan, many varieties of flowers and herbs are used as companion plants to attract beneficial insects.

Buds ripen in the field and are harvested in small batches and handled gently, just like high-end wine grapes, which are never stacked or compressed during harvest.

They are put into a room that is heated to 90°F (32°C) for the first 24 hours to release moisture into the air, which is collected by a dehumidifier to keep the RH low.

After 24 to 36 hours, the drying is slowed by increasing humidity to about 75-80% for a minimum of seven days. The climate is controlled to 60% RH and 65°F (18°C) or cooler. After the stems and leaves are evenly dried, the buds are ready for a six-month cure. Both buds and branches go into the cure; the buds go into unsealed but partly closed paper bags, and the branches are placed in cardboard boxes.

After six months, the buds are vacuum-sealed in jars and released to the market.

Growing Giant Terpy Emerald Triangle Plants with Mendo Dope & Greenshock Farms

Greenshock Farms and Mendo Dope grow the massive tree-sized cannabis plants the West Coast has become famous for. Their award-winning flowers have rich scents and high terpene content, which they attribute to their back-to-nature volcano-mound soil method and diligent work in breeding cultivars that thrive in the garden’s microclimate.

Greenshock produces one sun-grown harvest a year. Clones and seeds for the pheno hunt are started indoors in January and February under basic fluorescent fixtures. The plants root and grow vegetatively indoors in the winter and are then transplanted to one to two gallon (4-7.5 l) pots before being placed in a greenhouse in the early spring. By April they are planted directly in the ground and have grown 2 to 3 feet (0.6-1 m) high. When they are harvested in October, they will be up to 12 to 14 feet (3.6-4.25 m) tall and wide, producing an average of 8 to 10 pounds (3.6-4.5 kg) of finished dried buds each.

Each root system is planted in a volcano-shaped mound that rises about three feet (1 m) from the soil’s surface. Without the mounds, the plants would not grow as healthy or large. Mark Greyshock of Greenshock Farms says the practice is common with giant pumpkin farmers because it secures the roots in the ground, manages moisture, and increases oxygen at the root level while preventing root rot and providing the plant nutrients through layers of natural amendments to the native soil ecosystem.

The mounds are formed, amended, and replanted each year and throughout the plant’s growth and flowering through top dressing of dry amendments, including alfalfa straw, compost, manures, kelp, guanos, lava rocks, and trace mineral sand. Once planted, the soil will not be disturbed again. The goal is to provide a healthy root environment thriving with microlife to fuel the massive growth and flowering of the giant plants.

Cover crop seeds such as red clover and Dutch white clover are tossed into the top layers of the mounds early in the planting season. The rows of plants are interspersed with native plants, a technique Mark Greyshock learned in the 1990s while tending clandestine gardens in Southern California’s Santa Ana mountains.

At the time, blending the native plants in the garden was a technique used to help evade law enforcement, but Mark fell in love with the native plants and the bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds they attracted to the garden. He attributes the quality of the finished product to the garden’s healthy soil ecosystem.

Growing in Mendocino, they use regenerative farming practices that do not disturb the native redwood forest or damage the local native soils. Alongside every year’s “Avenue of the Giants,” or the massive plants grown from clones to harvest their flower, is a “pheno patch,” where more mounds are utilized to test the seed-plant variations of new cultivars they are experimenting with.

The Greenshock Mendocino farm is a partnership between longtime grower Mark Greyshock and brothers Daniel and Bryan Eatmon, aka Old E and Bleezy of Mendo Dope. Mendo Dope is known for its music and YouTube videos that celebrate the culture and communities of California’s Emerald Triangle.

Old E and Bleezy started working as cannabis trimmers in 2007. Gradually their home garden grew larger, which culminated in a raid by the Mendocino County Sheriff’s Office in 2013. Although the garden was within the legal plant count limit of 25, they were very large, which the sheriff claimed meant they were no longer legal. The garden was destroyed.

Photo: Mendo Dope

Shortly after California legalized cannabis, they paired up with Mark Greyshock to produce a range of new cultivars that could grow as giants through Greenshock farms using the Mendo Dope brand. The most popular cultivar of the moment is the Tropical Sleigh Ride, a winner of the highest-terpene flower and most interesting terpene-cannabinoid combination at the 2019 Emerald Cup. Their Passion Orange Guava “POG” took second place.

Other favorites in the garden include The Mendo Dope, a collaboration between Mendo Dope and legendary breeder Subcool, who passed away in February 2020. The Mendo Dope is a cross between Subcool’s Querkle and Locomotion. They have also produced several Tropical Sleigh Ride crosses: Peppermint Sleigh Ride, Trifle (Tropical Truffle x Tropical Sleigh Ride), and Spumoni Kush, a cross of Tropical Sleigh Ride and a legacy version of Barney’s Farm’s Vanilla Kush that Mendo Dope has nurtured for nearly a decade.

They have recently started breeding with CBD flowers. Results include two cultivars, Dr. Greenshock, described as a “perfect 1:1 ratio” of THC to CBD, each testing about 10%, with a high terpene content of 3.8%, and the flavorful G Lime Burst, testing at about 5% THC to 18% CBD. They hope the high-CBD sun-grown flowers will be a gentle introduction to cannabis for new users.

Pollen is collected and stored to pollinate selected plants in the pheno patch in late summer. The phenos must be able to adjust to the specific microclimate about 2,000 feet (610 m) above sea level near Willits, California. Just 20 miles (32 km) from the Pacific Ocean, the region is a coastal mountain range covered in redwood forest full of microclimates that range from hot and dry to moist and cool. In the Greenshock garden, summers are hot and sunny, but sometimes rain and even snow come early in fall, making it a challenge to harvest before the buds are damaged. This is why the pheno hunt focuses heavily on mold-resistant cultivars and why mold problems are rare outside the pheno patch.

At the start of the grow cycle, the plants are hand-watered. Once transplanted to the mound, they are watered using a drip system that rings around the top of the mounds and guides water away from the plant stems, keeping them dry to prevent mold as they grow as thick as tree trunks.

The growth of native plants between the mounds is encouraged. Photo: Mendo Dope

Wire cages are buried around the root ball to protect it from gophers and voles. Photo: Mendo Dope

Before the plants are placed in the ground, the hole is lined with wire cages to prevent gophers and voles from destroying the heart of the root ball. Another advantage of using wire cages is that they help the root system support the top-heavy plants from wind. Wire cages are placed around the plant to support the branches and spread them out so that they capture more light. As the plants grow larger, the supports are adjusted.

To control pests in the garden, they utilize integrated pest management (IPM) techniques like predators and traps. Dyna Traps are used to control caterpillars by capturing moths that lay eggs on the plants. The Dyna Trap has a small light and a fan that attracts and catches moths and little bugs.

The crop begins to mature around October, and colas and branches are cut from the plants as they ripen. The plants are dried in a dark room with dehumidifiers and fans to regulate the climate. After drying for one to two weeks, they are broken down into buds and put in a temperature-controlled room to cure.

Remo’s High-Tech, High-Yield & High-Efficiency Indoor Garden

Remo has been growing indoors since the late 1980s and likes to experiment with the newest technology in indoor cultivation. He documents his garden and postharvest processing on his popular YouTube channel UrbanRemo, where viewers get an inside look at the experiments he conducts in the personal medical garden he uses to explore and promote his Remo Nutrients line. Manufacturers send him new products to play with—sometimes even before they hit the market. The result is a high-efficiency, high-yield, high-tech personal indoor garden with a wealth of bud, hash, and other fun DIY by-products.

The Garden Space

Remo is permitted to grow up to 98 plants for personal use under Canada’s medical cannabis regulations. The entire garden is approximately 534 square feet (50 m2). The grow area is divided in two separate spaces; one space for propagation and vegetive growth and the other for flowering. The height of both rooms is 12 feet (3.6 m). The vegetative room is 8 by 20 feet (2.4 by 6 m), and the flowering room is 17 by 22 feet (5.1 by 6.7 m).

Lighting

Overall, Remo has experienced a 21% savings and a 50% increase in overall yield by switching to high-efficiency LED lights.

Both the vegetative and the flower room are exclusively lit by the latest technology in LED lighting. The vegetative room is lit with 8 Aelius Matrix 420 LED lights. The flowering space is lit by 20 Aelius REDDs. These lights are dimmable from 0 to 100. By replacing 7800 watts of mixed traditional lighting with 3360 watts of high-efficiency LED light, power usage has been cut by more than half.

Opposite: Remo eliminates pest and disease problems before they start using a combination of preventative measures and the Air Sniper. The Air Sniper effectively kills airborne pathogens using UVC light. Air Sniper equipment is easily integrated into indoor cultivation spaces of all sizes, from a personal garden like Remo’s to a large-scale industrial facility. A combination of stand-alone, in-line (integrated with HVAC systems), and hybrid units means Air Sniper has the right solution for the needs of any space.

The lights are affixed to automatic lifters controlled through the Stratus Control Unit and can be quickly and easily adjusted up and down with a touch of a button to adjust to plant growth.

Climate Controls

Closed Spaces

Remo practices closed environment agriculture. His gardening space is completely sealed, and there are no intake or ventilation fans of any sort. A good-quality charcoal filter is used to help control smell.

The air in the room is treated and sterilized by a UVC-light unit called the Air Sniper. The UVC light kills any airborne pathogens.

Stratus Controller

The Stratus Controller controls the entire grow room. All electrical equipment including lights, air-conditioning, dehumidifier, and CO2 system are powered through the controller and managed through a mobile application and sensors placed around the garden. The controller has sunrise and sunset capabilities, which prevent the spike of humidity and temperatures that can happen with regular on/off timers. In this way it better mimics nature.

Remo Nutrients provides a complete nutrient system with a total combined 52 ingredients that provide macro and micronutrients plants require for growth.

Vapor Pressure Deficit (VPD)

Remo follows a VPD chart to keep the space similar to hothouse conditions, which he says has also contributed to the increased yield from his rooms. Since he began using these techniques, Remo says he doesn’t have mold or mildew problems. Remo stresses that understanding VPD is critical to increasing yields. He averages over four pounds (1.8 kg) per light. (See Air, Temperature, Humidity & Qualities.)

The vegetative space is set to 85°F (29.5°C) with 70% RH. The flowering space starts out at 84°F (29°C) and about 65% RH. Each week the temperature is lowered by 1°F (about 0.5°C). By the end of week eight the temperature is reduced to 76°F (25°C). Each temperature adjustment is accompanied by an adjustment in RH as well as adjustments for the three different rates of transpiration the plant will experience between the beginning and early flowering to midflowering and late flowering.

Closed Loop Air-Conditioning, Dehumidifier & Water Purification System

Both the air conditioning and the 310-pint Anden Dehumidifier recapture moisture from the air and transfer it to a water purification system attached to the wall in the flowering space. Here the water is purified using UVC lighting and fed back to the plants. Although a little additional water is used in the beginning and sometimes in the middle, the garden otherwise operates on 100% recycled water. Remo has been using this process for so long that he has used the same water for years at a time.

CO2 Supplementation

Sensors on the wall trigger the release of CO2 over the canopy. Remo sets the levels to 800 ppm over ambient levels or about 1100 to 1200 ppm. A 20 pound (9 kg) tank supplies the flowering space with ample CO2 for about 7 to 10 days.

Media, Nutrients & Fertilizer

Remo uses coco coir and Proterra growing media in six gallon (22 l) square pots. Plants are fed exclusively by Remo Nutrients, as the garden is designed for experimenting with new popular varieties and Remo’s line.

Remo saw a need in the marketplace to create a more efficient line by “stacking” ingredients to create fewer bottles for the whole grow cycle. Remo Nutrients are easy-to-use blends of premium synthetics and high-quality organics that are designed to work with probiotic systems. Remo Nutrients is a vegan line, with no animal by-products.

Remo Nutrients provides a complete nutrient system. In addition to the two-part micro and macronutrient base provided in the Grow and Bloom formulas are four other additives with a total combined 52 ingredients: Velokelp, Magnifical, Astroflower, and Nature’s Candy.

Velokelp combines two types of cold-pressed extracted kelp, B vitamins, humic acid, fulvic acid for mineral uptake, and 0.6% orthosilicate. Magnifical is a Cal-Mag supplement with an N-P-K ratio of 3-0-0. Astroflower is a phosphorus-potassium booster that helps develop bigger, denser buds.

Nature’s Candy is a carbohydrate-loading product full of sugar, specifically inverted cane sugar and blackstrap molasses for terpy pungent flowers, along with 14 amino acids that are natural building blocks of life.

Visit RemoNutrients.com/Calculator for customizable feeding schedules. Photo: Remo

Cultivars

Remo has a genetic collection of over 500 cultivars, mostly seeds. Most genetics were acquired from other growers and breeders he met at cannabis events over the last 15 years. Some viewers of his YouTube channel have even sent branches in the mail, which is how he started growing one of his favorites: Frosted Fruitcakes. He tends to grow current popular varieties to experiment with the nutrient line. This garden features Zombie Kush, Girl Scout Cookies, Fruity Pebbles OG, Sin Mint Sorbet, Wedding Cake, Oreoz 1 and 2, GMO, Sour Tangie, Strawberry Banana (both from DNA Genetics), Lemon Kush, Blue Jelly, and Island Pink.

Pest & Disease Management

Pest and disease problems are eliminated from the start by using the Air Sniper in the sealed environment combined with preventive measures. Remo doesn’t like to use sprays on the plants and instead will use sticky cards and predator bugs such as cucumeris, persimilis, and/or nematodes as a regular preventative program every six weeks.

He doesn’t spray for powdery mildew; instead, he uses high heat to kill the mildew. Temperatures above 77°F (25°C) with matching humidity set according to the VPD chart will eliminate the problem.

Harvest & Processing