Thousand Wells, Arizona-Utah

September

AN ACCOUNT OF WATER WAS ONCE BROUGHT BACK FROM a region of sand dunes in the Gobi Desert. In the first decade of the twentieth century a woman had gone in search of an extensive lake, called the Lake of the Crescent Moon, rumored to be deep within the dunes. Working as a missionary, she spent time traveling the region, inquiring into the lake as she went about. She was told that it was in the Desert of Lob, beyond many crests of dunes. The directions became more specific as she came closer, until she left the town of Tunhwang and walked four miles into the dunes to find this exiled body of water. She described her feet slipping in the sand and how, exhausted, she scaled the last dune to peer over the top to see water below.

Swales and crests of sand loomed five hundred feet above the lake, casting shadows across its untroubled water. She had no explanation for this anomaly. It was perhaps thousands of years of rainwater gathered on a buried hardpan of rock. Or it was the one spring where dunes fed their sparsely gathered precipitation. She wrote, “Small, crescent-shaped and sapphire blue, it lay in the narrow space dividing us from the next range like a jewel in folds of warm-tinted sand.” The image haunted me; I have always thought it to be true—an enigmatic, ultimate source of water. There are such places.

The ulterior store of water—not just a place to drink, but a jewel like the lake in the sand dunes—was an elusive image, formed in my mind but extremely difficult to locate. Some people had suggested to me that if such a lake was out there, it was already known, cordoned off, confined to a national monument or a state park. But I had been out searching for water for so many years in places unknown, finding bits and pieces, that I came to believe it would be there. I tried not to be a clown about my belief in some great, unaccounted water source. I traveled efficiently, keeping tidy camps, walking at night when necessary, and looking for water only because I had to. Always in hopes.

In this place, west of the Four Corners and Navajo Mountain, along the Arizona-Utah border where the Great Basin Desert comes south, I had found no water at all. The heels of my boots dug into the peach-colored sand of Navajo sandstone. I sat with my back pressed against a rock wall, my body seeking shade, scooting another inch tighter as the sun moved in. Every once in a while I stuck my hand forward to feel sunlight playing down like a clean, odorless poison. The September sky was as curved and blue as a robin's egg, a color and shape that implied scant moisture in the air and a far walk to the horizon. My partner, a broad-shouldered man named Tom Vimont, breathed heavily in the shade ten feet away. His eyes were closed, his jaw slack against the sand. Morning. We had already walked as far as we could in the last cool between darkness and 10 A.M. Now the day had begun. Heat was everywhere. When the sun crawled onto my boots I could feel it through the leather. In my toes. I stood and hoisted my backpack. Tom opened one of his eyes.

“I'm going,” I said.

“Okay.”

“I'll be at the next ridge. The white one with those boulders fallen on the west side.” I pointed out there. He did not look. I told him I would wait for him in that next shade.

“Whatever,” he said. “You go get lost in the heat. I'll find your bones when it cools off.” He closed the one eye.

When not alone, I usually travel with one other person and we share few words during the day. I carefully choose the people I join for these walks, making certain they are not too abrasive or loud, or they carefully choose me. Tom is of a different quality, vocal and prankish. I travel with him because he rousts me from my quietness. He dances naked on rocks shouting obscenities to the sky, not caring if God hates him. He was once a mountaineering instructor. He sang in a punk rock band, was hired as an exotic dancer. When he was fifteen, as he so often enjoys saying, he got his girlfriend pregnant and stole a car, drove off with her to get married on the other side of the continent. I travel with him because when I say I'm heading into a piece of desert I know nothing about on the off chance of finding water, he grins and asks When do we leave?

Leaving Tom half asleep in the shade, I walked into the heat. From a distance, this is an inconspicuous land. It is a tilt rising gently to a high ridge at the roof of the formation called Navajo sandstone. It looks barren, uneventful. I had seen it a number of times from twenty or thirty miles away and never considered walking in this direction, always having been bound for more spectacular country. But on the voluptuous stone of the Colorado Plateau nothing is ever as it appears. There is constant potential. The desert is not dried up and empty as if it might blow away like the seeds of brittle grass. It is the bones of the earth brought to daylight, half stuck out of the ground so that winds and flash floods constantly reveal more. Just as it is beneath our own flesh, the bones are the sturdiest, most lasting parts. With their hollowed sockets and deliberate lines, they set a foundation upon which the flesh of forests, mountains, and oceans might accumulate. Only here, the flesh is gone, the last of it turned to dune sand.

Waterpocket at sunset

The convolutions grew as I walked. Forms of carved rock rose above me. Colors shifted between the red of salmon and a cream white, highlighting changes in the shapes of rocks. Navajo sandstone in particular wears into the most sensuous of shapes. It erodes into moons and the backs of whales across which I walked. I had studied a master's thesis by a man who did his field research somewhere in this area, a man who had spent time searching the rounded top of the Navajo. I was told he was ambitious with his travels in the desert, and that his skin had hardened against the sun. He had been studying habits of the crustacean species Triops, a creature an inch or so long, looking like a cross between a horseshoe crab, a trilobite, and a catfish. It is the oldest living animal on the planet, perfectly matching fossils from 180 million years ago, each part of its anatomy unchanged since then. It is an aquatic species, unable to survive on dry ground or even mildly damp ground. It must have some deep pocket of gathered rainwater that lasts weeks or months. I figured that there had to be a fair number of these pockets to support enough Triops for a master's thesis. Between the woman who found the clear lake in the sand dunes and this man who had found Triops on blistering sandstone, the place with water must exist.

Tom and I were both carrying whatever amount of water seemed prudent. I don't like to haul more than a couple of quarts at a time. A gallon is enough for one day of drinking, but that is too much weight, eight and a third pounds. Water would need to be found by nightfall. I flooded the air ahead of me with faith that radiated away, then disappeared in the dryness like a hot afternoon breeze that cannot stir a leaf.

Water created life the way it creates creeks or springs. It did this, I think, so it could get into places it could not otherwise reach, so that I would act as a vehicle carrying it into the desert. As living beings, we consider ourselves to be independent with our fingers, arms, and voices. Unlike alpine creeks, we are not all tied together, so we imagine that we each behave with free will. We can tie our own shoelaces and write poetry. But especially as I drink the last of my water, I believe that we are subjects of the planet's hydro-logic process, too proud to write ourselves into textbooks along with clouds, rivers, and morning dew. When I walk cross-country, I am nothing but the beast carrying water to its next stop.

Sit in a car on a cold night and you will fog the windows with the water you carry. Touch your tongue or the surface of your eye and you will find water. Stop drinking liquids and see how difficult it is to maintain a coherent thought, and then, days later, how difficult it is to remain among the living. Specialized equipment has been designed to find a person behind a cement wall by bouncing 900-megahertz waves through the wall and off the liquid in the human body, as if we were all water-filled balloons unable to hide our cargo.

We are not as ephemeral as clouds. We cannot dissipate at the first downtrend in humidity, then expect to re-form elsewhere, so we have developed legs to walk us to the shade and hands with which we can construct faucets and swimming pools. Like any stage of the hydrologic process, we have our own peculiarities, our organs making us nothing more than water pools or springs of bizarre shape, filled with pulsing tubes and chambers.

Within my body I escorted well over a hundred pounds of water into the sand and rock on this day. Another four pounds were in my pack, for drinking. I carried this water across the supple shapes of small dunes and along the better footing of stone slabs. Whenever I scraped against a rock too hard, out leaked blood, nothing but glorified water. Tipped saucers of rock leaned upward and I dropped off their backsides, walking around clusters of shoulder-height juniper trees screwing out of cracks in the rock. Two ravens crossed. Their wings sounded like cardboard whooshed through the air.

I removed my pack and turned up through the boulders at the far ridge. At the top I pulled out binoculars and could see Tom, who had begun to move, groping through his gear a mile away. I watched his candid gestures, how he threw his head back to drink. Ahead I saw farther ridges, and beyond them a massive dune of sand rising five hundred feet to where it slept against a higher ridge.

About a hundred yards east of where I had just walked, freckles of water-filled pockets extended over a sandstone plain. I squinted, then started counting. They looked like fallen pieces of sky, so delicious that dry seeds would split open just to know of their presence. Each sat in the open as if lounging, unaware of the aridity surrounding it, mocking the sun. They had been beached here by thunderstorms, slowly hissing into nothing beneath the sky. I counted twenty. Maybe twenty-five when I included glints of reflected light from behind rock swells. These were sizable rainwater depressions, some of them the largest pockets I had ever seen in sandstone, thirty feet across.

In the Sonoran Desert they are called tinajas. Here on the Colorado Plateau they are waterpockets, generally different in structure than a tinaja, usually pocked across open plains of sandstone instead of in the line of a drainage. As it sits for different seasons over thousands of years, gathered water carves its own hole in the easily eroded sandstone. The longer the hole has been there, the deeper it becomes, the more water it holds. Hydrogen bonds in the rainwater pry sand grains from the rock, deepening the hole.

I jumped down from the ridge, grabbed my pack, and stumbled along the slope to intercept Tom. I shouted once, shouted the word water, and pointed east. My voice came back from every direction.

Tom motioned to his ears. Couldn't understand.

We met at a ravine and he waited in the shade of a piñon for me to catch my breath. I told him that there were at least twenty-five of them. We would have walked right past them. I'll show you, follow me. Down into the white sandstone, where it mingled slightly with red, we followed sand, then exposed rock. This opened to a rolling dance floor. On the floor was water. It had gathered from rain, but was substantial and would stay for some time. At a quick guess, I figured about fourteen thousand gallons rested in the rock before us. If water had created life in order to reach odd places, it created waterpockets in order to stay there.

I walked among the pools forgetting Tom was with me, letting me stride ahead. I did not watch each pool. I let them pass, feeling the prosperity of not having to bow and drink at each one. Some were thin and snakelike, others shaped like a woman sleeping on her side. There were crescents and deep envelopes, none of them feeding plants. They were all in bare rock, each one supporting Triops shrimp as well as a flood of clam shrimp and fairy shrimp. I swallowed my saliva, my throat dry. I stopped at one of the deeper pools. It sat twenty-five feet wide.

Tom stepped beside me. He did not wait. He stripped off his clothes quickly. Naked at the edge of the water, he posed theatrically with his hands praying to the sky. He is a big man, looks like he could crush rocks with his fingers. He glanced at me, grinned, and entered the water.

I stripped and followed. There could have been discussion about us damaging the ecology of the hole. There was not. Even though filter-feeding organisms might profit from our flailing and stirring of sediment, I would never profess our presence to be a benefit. But it was hot outside, and there was water.

When I entered, I did not jump. I slipped in at one end until only my face remained above the surface, my body seizing for a moment and then relaxing. It was not the coldness of the water that brought the quick seizure, but the absoluteness of the transition between desert and here. The shift was not slow or buffered. The only boundary was this perfect lens of blue, matching the cloudless sky for every value of color. The water turned smooth after a minute. My arms and legs hovered half-cocked, the way they do for sleeping astronauts. My face floated on this liquid mirror, surrounded on all sides by hot plates of sandstone tilted at the sky. I lifted a toe to penetrate the surface, watching rings drift outward, their movement opening a passageway from an inconceivable world.

Tom crawled onto the rock, his body doused, draining water back to the pocket. Water ran the depression of his spine, off his face, from between his fingers and toes. He rolled onto his back and the heat worked into his skin from both the rock below and the sun above. He closed his eyes. His mouth opened. In a groan, he said Yes.

Leaving Tom half-asleep on the rocks, his body surrounded by a thin, evaporating sheet of water, I took a notebook and skirted the pools barefoot, counting them, figuring which had what combination of crustaceans. Each seethed with life. The shrimp grazed on smaller organisms from the floors or from the open water, undulating their appendages so that every liter was guaranteed a good going-over. The deepest pocket, its floor hidden from daylight, belched Triops from the darkness below. Some had only fairy shrimp, which patrolled the water like schools of squid, trailing their teeming shadows over the round floors. These were slender and transparent of body, showing rhythmic sways of feathered appendages, which both propelled them and gathered oxygen. Other pools specialized in clam shrimp, with bodies similar to those of fairy shrimp, but seated in a bivalve shell thin as onion skin.

The Triops were by far the largest and most aggressive compared to the milquetoast fairy and clam shrimp. Their undersides, decorated with appendages of a slightly blue tint, gave them the appearance of crafted Japanese fans. They quarreled like cats whenever encountering one another, sometimes killing and consuming neighbors, hauling their bodies away. They scraped the floor with urgency, tracing the shapes of question marks as they arced through the water.

The species looks ominous with its shield for a carapace and two poppy-seed eyes seated next to each other, a fleshy, pronged tail ringed like that of a rat, and wired sensory organs splayed off the front. In my palm they slung their bodies with electrified twitches, trying to return to the water. Once returned, they got back about their business without pause, showing a distinct lack of memory. Still, I was hesitant to touch them, fearing whatever mechanism they had developed to defend themselves against seafaring dinosaurs. Creatures like sharks or scorpions or dragonflies are often considered to be some of the oldest on the planet, but they represent only an old style, an old type of organism. Their bodies have changed in the hundreds of millions of years while Triops has not. It is the same now as when it left fossils of itself.

Theoretically, the one thing that placed Triops into these holes was the evolution of predatory, suction-feeding fish about 300 million years ago. The only defense these crustaceans had was to move out of the oceans and into these loose affiliations of water holes, surviving by following the rise and fall of various climates, moving from one temporary water hole to the next across the planet, waiting out dry times in the form of eggs parched as dust.

Desert water holes produce the oddest of non sequiturs. In Cabeza Prieta, at the Mexican border, the eight-inch-long Colorado River toad, Bufo alvarius, has been found in a number of tinajas. Some of these toads, so large that their skin is folded, robelike, were found in tinajas 140 miles from the Colorado River. Along that straight line happens to be the driest land of North America.

How does the toad or a Triops make the trek to some small pool of water? A list was once compiled recording items known to have been unexpectedly delivered by the sky, mentioning spores, pollen grains, algae, diatoms, various microscopic single- and multiple-celled organisms, rotifers, living mites, pieces of dried algal mat, mussels weighing up to two ounces, fish, salamanders, frogs, turtles, and rats. If it seems unlikely that aquatic animals can be regularly transported to their water holes by wind, keep in mind that among these falling turtles and rats, there have been nearly a hundred accounts of fish raining from the skies.

Just before eight o'clock on the morning of October 23, 1947, fish numbering in the hundreds fell upon the streets, houses, and walking commuters of Marksville, Louisiana. Several people were struck directly by falling fish, most of which were either frozen or at least very cold. Their temperature suggested a recent ride through high clouds, meaning they were probably sucked out of a lake by an atmospheric disturbance, something that in the desert is commonly called a dust devil.

A biological investigator from the Department of Wildlife happened to be eating breakfast in a Marksville restaurant when the waitress told him about the thudding sounds outside. He immediately moved to the streets, where he collected samples of largemouth bass (one of them being nine and a quarter inches long) and various species of sunfish, pronouncing them to be “absolutely fresh, and…fit for human consumption.”

More than likely, however, organisms deposited in waterpockets by wind would be smaller than fish or Triops. They would be algae and microscopic diatoms the size of ground glass. Desert rains are particularly rich with minuscule aquatic organisms, richer than mountain rains even, pulling down a dusty atmosphere of creatures, then directing them to waterpockets as they flow over the ground.

Still, wind and rain are not particularly efficient at relocating animals. The fish of Marksville did not benefit from the random rolling of atmospheric dice. They were, instead, ready for eating.

Hitching a ride with an animal heading to water offers far better chances. In 1930 a researcher sent a letter to an associate, mentioning, “When examining the contents of a frog's rectum yesterday in the course of our lab work I noticed several living ostracods.” An ostracod, commonly called a seed shrimp, is a water-hole crustacean much smaller than Triops. The creatures either had been living permanently in the frog's rectum or, more likely, were passing through.

Although a Triops or a Colorado River toad the size of a soft-ball cannot be comfortably passed by most rectums, their eggs can. When domestic mallards were fed dust from a desert playa bed that had been dry for several months, the ducks defecated the eggs of fourteen crustacean species including Triops. Some of these were brought to hatching within twelve hours.

As a more seemly way of travel, these same species also gather on the outsides of animals. A single dragonfly was once meticulously cleaned and found to be carrying twelve viable samples of unicellular algae, eight samples of filamentous blue-green algae, a rotifer (a microscopic aquatic organism), and fourteen other small aquatic creatures. One wasp produced nineteen species of animals and plants from around its wings and legs.

None of these dispersal methods are especially quick or predictable. The result is that species in water holes, the ones that can't get up and fly away, do not move around very often. They become genetically isolated over thousands, and then millions, of years. In 1992, after nearly all of the temporary vernal pools of California were destroyed by human development, researchers went out to catalog those still intact. Of the sixty-seven species of crustaceans found in the remaining pools, thirty had never been documented anywhere on the planet. People had to suddenly set about inventing names. A quarter of these newly found species were each found in its own pool among the fifty-eight pools studied, meaning there is not much motion between one pool and the next. What was lost in the hundreds of destroyed pools is unknown. Extinctions from ephemeral pools have probably been occurring at massive levels, banishing numerous species that have never been seen or even imagined by humans.

A study of such magnitude has not been performed on these Navajo waterpockets, so diversity between each pool is contained in the genes of these creatures and not in our papers and studies. Already I had noticed a number of different species among both fairy and clam shrimp. Walking barefoot, I had recorded twenty-eight waterpockets in the white sandstone. Some had floors of clean rock, some mud. There were floors dotted with swollen cacti that had blown in, floors of juniper berries, and floors of sand. Some of the water had the faint red-wine color of tannic acid from nearby junipers, while some were olive green and others absolutely clear.

These pockets led me farther east, where the dance floor ended, rising into a series of tall, narrow fins. Once I reached the fins, the skin of my feet growing sore against the heat and the kernels of rock, everything changed. I stepped up one of the backbones and looked down into a sea of waterpockets. I stood for a second. Then I crouched. There were over a hundred waterpockets below me.

This I had never seen. Nothing like this. The rock formations themselves were remarkable, having the configuration of egg crates with round water holes seated in the pits. I walked across the connected high points, looking down thirty or forty feet into smooth white craters on all sides where water had gathered. Each depression was entirely sealed from those around. I had to go back and get my boots. From there I kept counting, but I soon had trouble remembering where I had gone and where I had not. The fins and their cauldrons were beyond measurement. I put away my notebook at 138 waterpockets.

The only thing that could have adequately prepared me for this was to have walked in Cabeza Prieta. Following bighorn sheep off the Mexican border, my first discovery had been a bee-infested crack with twenty-two and a half gallons of water, my fingers trembling just to touch it, which allowed me to now see the garishness of this fortune on the roof of Navajo sandstone. Within a few hours today I had seen over seventy thousand gallons in water holes. This would have been unthinkable in Cabeza Prieta.

Tom joined me at the cauldrons before sunset. We left our clothes at a lip near one of the deeper holes. There we climbed in and sank our bodies. The sky became a confined circle. We spread our palms on the smooth stone as Triops bumped into our backs and burrowed beneath our feet.

We climbed out and, naked in the copper light, walked the narrow bridges, casting shadows of our bodies on the next fins over. The land, with all of its turns and holes and cryptic back rooms, rose up and swallowed us.

We returned at night and I lingered at the dance-floor pockets, near our small camp. Stars of a moonless sky reflected from the water so that the sky looked as if it had shattered and fallen messy across the earth. I was able to map the Milky Way by walking a circle around one of the pockets. A few hours before sunrise, a thunderstorm took the sky, rumbling and churning to the south. I woke and moved to the water, where I sat with knees against my chest. The pockets threw back the electric-white flare of lightning, the desert thumping with thunder. I waited for rain, to watch water run into the holes. Instead the storm broke in two, swerving to the east and west, offering only drizzle here. As the storm moved north I watched lightning crack the water's surface.

Eventually I returned to my own camp, which consisted of a sheet and a ground pad. Crickets got back to their Morse code after the passing storm. I lay on top of the sheet and fell asleep, my body peppered with light rain.

In the morning we packed and left, walking east. I had originally wanted to stay for days at these waterpockets, but the territory was vast. We had food for only four days and neither of us knew anything about the territory. First we crossed the cauldrons, stopping to stare into the pits. Then we descended a narrow canyon, pushing through crowded junipers and the prodding limbs of rabbitbrush into a broad wash that separated the last region from a taller cluster of fins ahead. In the wash were sand dunes fortified with bunches of Indian ricegrass that kept the valley bottom from blowing down to bedrock. Our footprints sank and caved in on themselves as we plodded to the next escarpment of sandstone, the canyon shaping around us as if we were being swirled up into a dust devil.

This took us several hundred feet above the floor of the wash, leading to the tallest of fins. From there we looked down into numerous vaults of water. Our packs hit the ground. We scattered, walking lines of stone that laced over these new pockets, even deeper than those before. There were more at this location, many inset by fifty and sixty feet, leading into tiered holes stacked one above the next. Some were so deeply inset that rims heaped up like excess clay on a potter's wheel. In the few pockets that held no water, sand had collected. On the sand grew juniper, ricegrass, foxtail, purple asters, yellow spiny daisies, scrub oak, broom snakeweed, and prickly pear, each garden its own particular arrangement. The rest had water. Cones and bowls and tubs of water.

I kept shouting over to Tom that this was beyond the realm of reason. He shouted back words of disbelief, then disappeared into one of the holes, his voice coming out as if from a barrel.

One of the early government surveyors of the canyon Southwest, Major John Wesley Powell, told of water like this. Giving vague directions, he wrote that one day in September 1870, he was traveling along the foot of the Vermilion Cliffs, having found little water other than briny springs. The next day he climbed a cliff to a “billowy sea of sand-dunes” where he found canyons wrestling into a tilted mesa top. “On the slope of this ridge,” he wrote, “facing the mesa, there is a massive homogeneous sandstone, and the waters, gathering on the brink of the ridge and rolling down this slope, have carried innumerable channels; and, as they tumble down precipitously in many places, they dig out deep pot-holes, many of them holding a hundred or a thousand barrels of water. Among these holes we camped, finding a little bunch grass among the sand-dunes for our animals. We called this spot Thousand Wells.”

An etching by Thomas Moran and W. J. Linton accompanied Powell's description. The etching showed two Indians, one on hands and knees to drink from the largest of a series of oval pools.

This spot Tom and I had reached was Powell's Thousand Wells. It could be no other place. Even with the vagueness of Powell's directions, it matched. We decided to stay on task. We turned to the southeast, which took us from the waterpockets and sent us to lifting tables of sandstone. Quickly, I entered the mode of desert walking as my breathing became metered, my thoughts simplifying into bare bones. A straight-faced walk. Hot. Still air. I picked up small rocks or the bones of animals, then set them back without having formulated a thought more profound than bone or rock. I could hear the crunch of Tom's boots on the ground a quarter mile behind. I saw the way he moved, how he had accepted the desert, how his thoughts had centered as he sought routes over bulges and boulders.

As soon as I felt at ease, taking on the rhythm of walking in heat, I came to water again. This was in slanted, loose shelves of red sandstone where I would never look for water. Deep red sandstone is not as pure or as tightly packed as white sandstone, and never seems to hold water as well. The position of the rock, the angle of the bedding planes, was all wrong. I could not even find a drainage that would have filled it. The only way to get in was from the sky. My comments of impossibility became instantly hysterical as I waved my hands in the air before this pool, forty feet across, the largest we had seen. This whole region was absurd.

We removed clothing in a fashion that was becoming routine, leaving our own brand of piles: socks stuffed in boots, my notebook out of reach of wet hands, his clothes in more of a pile and mine more in a line. We sank into water the depth of our shoulders. Instantly we became playful, embarrassingly so as we made the water slosh back and forth unnecessarily until it tipped out one end. Then we walked, drenched, on the surrounding rocks. The sound of slapping water, the deep swallows made only by large masses of liquid, was almost too much to bear. I stood at the edge of the waterpocket, where much of the desert dropped off below, showing pockets of even greater size, and lifted my arms straight into the sky. Beads came down my body. This was abundance.

We walked to higher country, spending hours working toward a stretched dome of red sandstone. The tables steepened in the last mile to this highest point where the uplift broke its back, falling twelve hundred feet to a chasm below. The cliff was as smooth as lake ice. A rock could be dropped and it would not once touch the wall. Just beside the edge, as if lifted onto a pedestal, was a waterpocket. I told Tom that what we were witnessing here made everything I had ever seen inadequate. Tom laughed at me, said that I always say that. We go to places for particular reasons, he said. We came here for opulence.

I had not been counting religiously, but we had now passed between four and five hundred waterpockets. Maybe 300,000 gallons of rainwater. My careful counting of waterpockets the day before felt like a prank on myself.

As we slipped into the hole, our arms draping across its rims as if over the back of a couch, I said to Tom, “This has been years. I knew it would be here. If I looked long enough I would find it. I've been trying for years. Years.”

Skirting a pool that measured about one hundred feet in length, we could see a prickly pear cactus lurking in the depths. It was surrounded by Triops and a cloud of fairy shrimp. The cactus had not fallen in. It had grown there prior to the water, indicating that years of drought must have preceded this water. When this pool is dust, it must retain the seeds of aquatic life for however long it takes a cactus to grow.

To survive, these aquatic-desert organisms have taken an evolutionary course that rejects mechanisms of survival used by most everything else. Bypassing all accepted notions of life, they cope with extremely long periods of drought that would kill every jackrabbit and human out here. They shrivel up until they are dry as cotton balls, releasing all of their water, entering a state known as anhydrobiosis. Life without water. Basically, they die, but with the loophole of being able to come back to life.

Anhydrobiosis is dehydrated life—life shrunk down to its most primary aspects. No energy is spent on what would normally be considered to be living. The participants become sealed containers against the world, cells turning from living structures into reinforcement material. Sensitive organs are tucked away into specialized membranes, like wine glasses wrapped in newspaper for a move. Molecules, mostly a disaccharide called trehalose, are produced to shore up the shriveling internal structures. The organism's insides become crystalline, a material very similar to the liquid crystal in digital watches. A dehydrating roundworm converts a quarter of its body weight into this trehalose material before going completely dry, coiling into a compact circle and reducing its surface area to a hardened bulb about 7 percent of the original size.

If an anhydrobiotic organism regularly lasts for three weeks from egg to death, it does not matter if one hundred years of drought are placed in the middle of the life cycle. It will still live for three weeks, the extra hundred years being nothing but a pause on the biological clock.

Abandoned in dry water holes, these barren animals can be exposed to heavy doses of X-rays, gamma rays, neutrons, proton beams, high-energy electrons, and ultraviolet radiation with no ill effects. Embryonic cysts of an ephemeral pool crustacean were actually dangled outside of the space shuttle, exposed directly to the cold and radiation of outer space, and were later brought back to earth and added to water, where they came to life within minutes. The universe could be accidentally colonized by such creatures. In a sadistic array of experiments, adult tardigrades, known also as water bears, were once kept for eight days in a vacuum, transferred into helium gas at room temperature for three days, and then exposed for several hours to nearly -450 degrees Fahrenheit. Placed in water at room temperature, they returned to life, no questions asked.

Perhaps the most telling experiment is that anhydrobiotic cysts of crustaceans are packaged and sold to children. Often they are sold as “sea monkeys,” presented on packages with the females wearing pink bows in their sensory organs, and families of smiling crustaceans reclining in underwater living rooms (the wife wearing an apron, the husband smoking a pipe). At a toy store I once bought an envelope of Triops eggs (Desert Dan brand); the print on the back informed me that they would live twenty to seventy days, “unless, of course, they are eaten alive by their cannibal siblings.” The packaging read:

TRIOPS

From The Age Of

DINOSAURS

Watch

Their

AMAZING

AQUA-BATICS

They're

ALIVE!

Just Add Water

They Hatch In

24 HOURS

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO GROW INSTANT PETS

I put them in a cup, and within twenty-four hours small objects could be seen scuttling across the bottom. No false advertising. I instantly had pets. And they were, indeed, from the age of the dinosaurs, as Desert Dan had professed. The aquabatics would come later as they began eating one another.

What truly separates these dehydrated organisms from every other living thing is that they have no metabolism. Even scientists who contend that all life requires a metabolism admit that anhydrobiotes must exist at the minutest fraction of the speed of normally metabolizing specimens. If this were a human, the heart would beat three times every year. But there does not appear to be even a slow heartbeat in anhydrobiotes. Using radiochemical assay, researchers have not been able to detect enzyme activity in any “live” organisms below 8 percent water content by body weight. There appear to be no working parts in these organisms: they are as dead as rocks. If a Mars lander were to be given a scoop of dust from a dry water hole and allowed to run all of the spores and shrimp eggs and desiccated adults of various species through its battery of life-finding tests, it would conclude that no life was ever present.

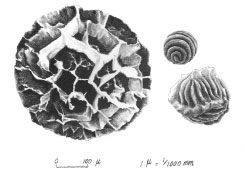

Water hole shrimp eggs

The question then arises as to what actually defines life. The crustaceans in limbo are not dead. Yet a viable egg of a desert toad cannot be differentiated from a nonviable egg until water is added and the egg either hatches or does nothing. Death and life in this case are structurally identical. One scientist, especially preoccupied with this topic, slipped out the words “cosmic metabolism,” but quickly dismissed this as a notion with little meaning in the biological context of metabolism. In the case of these creatures waiting for the next desert rain, he commented, life is more a quality than it is a quantity. It cannot be defined or measured by our tools, but it is there, perhaps more philosophical than detectable. The basic constituents of life are not at all what we had scientifically imagined.

How long can these creatures actually last before the arrival of rain? Shrimp such as Triops last for decades, at the least. They have never been kept longer than thirty years, while evidence suggests that they may survive for centuries. Again, at the least. Because adaptations are similar, they can be compared to seeds awaiting germination. Although data are not firmly proven, a seed of an arctic lupine from the Yukon was viable after 10,000 years. A dormant seed from Danish soil was viable after a proven 850 years. An example that seems most fitting comes from a Canna compacta seed that was recovered from an archaeological site in Argentina. The specimen was found enclosed in a walnut shell, which was part of a rattle necklace excavated from a tomb. After lying dormant in this tomb for 600 years, the dry seed was removed and placed in soil. Unfazed by this long period of quiescence, the plant produced a healthy root system and within ten days presented its first leaves. Reaching a height of six and a half feet, it flowered, finally showing itself to be a particular species belonging to the ginger order, Zingiberales. It fertilized itself and produced seeds that fell from the flower in proper sequence. It came just like that, simple as waking in the morning.

Because the rigors of the dry, almost lifeless period are more taxing than the wet times, the actual shapes of creatures-in-waiting are more visually complex as anhydrobiotes than as productive adults. Animals thought to be of the same species were found to be completely different when the structures of their anhydrobiotic cysts were studied.

There is always an artful construction to these waiting organisms, revealing an interior genius within nature. Seen through an electron microscope, anhydrobiotic cysts are a gallery of architectural styles. The closer the view, the more complex they become, with passageways and pillars and sponge platforms enclosing arrays of spikes and welded orbs, each of these shapes designed for some unknown, peculiar function. In many ways, they are similar to pollen grains or snowflakes, their composition symmetrical, intricate, and enigmatically individual. Sealed against complete drought, a fairy shrimp, Chirocephalus salinus, surrounds itself with pastrylike structures, each raised from the surface and arranged into pentagons. A clam shrimp cyst bears the topography of a rib cage curved into itself to form a sphere. Tanymastix stagnalis is a flying saucer with a pouting equator, its surface as dimpled as that of a basketball. Complicated and unrepeated between species, the shapes are nothing but a response to incredible adversity. Since the anhydrobiotic animal has no moving parts to defend or transport itself, it must make parts that work even when the animal is basically dead.

Biologically these waterpockets are the edge of the earth. To say that periods of drought present the only antagonism to life out here would be untrue. The entire cycle of wetting and drying refuses calendars and predictions, working the inhabitants so hard with instability that adaptations must be honed to the intricacy of fine lace. Pools dry and fill at irregular intervals, relying on mercurial thunderstorms, topping off in the winter, carrying three days of water in the summer, staying full for five months, then dry for two years straight.

Pool water will easily go from 60 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit between sunrise and afternoon. Then, during dry times, the barren surface, with its anhydrobiotic life poised for the next rain, will reach a summer high of 158 degrees. Daytime oxygen levels in the water jump by 88 percent, plummeting at sunset while, in the coming dark, acid levels rise by nearly a third.

An aquatic kingdom that turns its chemistry inside out between day and night, and exists every now and then in a scalding desert, invites not resilience as much as it does ingenuity. One observer visited an Arizona stock tank for each of the nineteen days that it held water after a heavy summer rain. Nearly twenty species of invertebrates and amphibians appeared during this time, and he took note of each. Predaceous beetles, Eretes sticticus, arrived as eggs after adults flew in from unknown water sources to lay them. They hatched into thousands of beetle larvae. Their development seemed to follow in perfect stride the slow vanquishing of the pool. On the nineteenth day, at 10:30 in the morning, the pool came very near to drying. En masse, the beetles, which had only recently reached their adult phase, suddenly produced an intense, high-pitched buzzing. Then, while the man stood watching, the entire group of beetles lifted into flight at once. The swarm set off to the southwest, disappearing at the horizon. Within one hour the pond went dry.

This kind of prophetic knowledge is not uncommon among dwellers of ephemeral waters. The adaptation is called phenotypic plasticity, meaning the ability to alter the body's shape in step with its environment. Toads and fairy shrimp and beetles will shrink and stretch their growth rates in precise cadences with the pool's life span. Development rates in water holes depend not on the original size of the pool but on how fast it is drying. Thus small pools do not necessarily produce small organisms. Rather, pools that dry quickly produce small organisms because the animals must develop rapidly, resulting in dwarfed adults. It is not the actual volume of water that is perceived, but how fast the volume is decreasing.

No one yet knows how this is perceived. After numerous studies, mostly involving mosquitoes, researchers have been left guessing, suggesting that the organisms distinguish the time or effort necessary to move from the top to the bottom of a pool, or that they gain cues from increased crowding. It could even be that they discern a changing volume of air in their tracheal systems during descent to the bottom of the pool. Whatever it is, these organisms know exactly how long their habitat will last. In the case of Eretes sticticus, it was down to the hour.

And once the pool dries, then where to? Like E. sticticus, the predaceous backswimmer Notonecta is able to leave the water and fly with wings it keeps sealed in a protective casing. To find the next water, it seeks polarized ultraviolet light reflected from smooth bodies of water, the same method used by water striders and dragonflies. Ultraviolet sensors are situated in the lower portions of its compound eyes. The backswimmer flies with its body tilted 15 degrees to the horizon, placing these UV sensors at a level that will strike polarized light off a flat surface at an optimum angle, initiating a dive-and-plunge response. Only a certain crossing of angles between its body and a polarized light source will send the backswimmer into a dive. It makes a pinging sound when hitting the flat hood of a darkly painted car mistaken for water.

A researcher in Arizona found that the best way to catch flying aquatic insects was to lay black plastic garbage bags on the ground just as a storm moves in. The insects tend to be out flying around storms, seeking new water, and the bags, like car hoods, reflect polarized ultraviolet light from a flat surface. The insects would plummet straight at the bags, which he had coated with glue. Notonecta did this to me once in Utah. These backswimmers began bombing me at sunset (when reflections from water are their most striking) until five of them had bull's-eyed into a cup of water in my hands. The mouth of the cup was only four inches across.

With life being tied into such knots and going through so much time, my own life had to be measured by completely different standards. Tom and I were lithe, short-lived creatures who would never know how to sleep for an entire hundred years. I kept scooping Triops from the water in cupped hands, holding them upside down, watching their fans run so quickly that, like a car wheel reaching a certain speed, they appeared to move backward. I did not do this to watch them as much as I did it just to touch them. This was a different strand of life from my own.

From the highest waterpockets we found the fast way down, skiing in our boots along the face of a sand dune, sand splashing the air from our soles. This was steep, hundreds of feet to the floor of a wide canyon. My path wrote cursive letters in the face, a clumsy language that would be erased by wind by tomorrow. Our habit was to walk from first light until dark, and tonight we slowed near sunset, coming into a deep well of pockets in the evening. One in particular caught Tom's attention. It was almost a perfect square, like a picture frame with richly wrought edges where water had left small erosional marks. Behind it was a long view, probably fifteen miles of desert seen between symmetrical colonnades of sandstone. He observed this pocket from several different vantages: first from directly above, then from a straight shot across the vista, then from a narrow cleft where he could sit on a ledge, and finally from just beside it.

We were both exhausted from the day, and the coming darkness caused our muscles to go limp. Our skin was burned from the sun. I joined him on the opposite side of the water and we stared at it for fifteen minutes. I rolled onto my back after a time and, seeing the first couple of stars, asked Tom if he wanted to swim.

He looked up, surprised to hear my voice. He spoke as if slowly coming awake. “No,” he said. “No. I think I'm good right here.”

The next day, on a broad shelf midway down a seven-hundred-foot cliff face, we found a long, narrow balcony of pockets hanging just at the edge. One pocket extended along the shelf and Tom stood high on a ledge, performing a headfirst dive into it. His feet plunged under last and he was gone. It was at least eight feet deep. I watched the pale image of his body arc below the surface like a shark. The image stayed in my mind, even after he broke the surface again and inhaled with a loud gasp. We swam in a pool nearly two hundred feet long, our arms tiring as we reached the opposite side. Half a million gallons out here, I figured, enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool. It was all contained within about two square miles of deeply ribbed and finned country, where we had been walking for three days, dawn to dusk. And this was just the water we saw.

We walked out at sunset, stopping once to gather a panful of water from a final pocket, shuttling it back to the shade where we prepared a meal of egg noodles and curry. From there, walking took us away from the water, down a canyon and into a region of sand dunes and blackbrush. There was no racing against the dark to get back to the truck. The night simply moved over us. Headlamps were never brought out. We walked on starlight, becoming groggy tired, talking with animation for thirty minutes, slogging silently for an hour, then exchanging bad jokes. We talked about what we would eat when we got out, how we would drive until finding a town with an all-night store. In our minds we were already gone.

Hours later, at one in the morning, we reached my truck and within three minutes of driving had it foundered oil-pan-deep in loose sand. Tires spun helplessly. When I walked around in this sand I thought of Colorado's April snow, how it sits on the ground like goose down. We got the truck out of one hole with swatches of carpet stuffed under the tires, only to make it three feet farther along the road, burying ourselves again. Eight times this happened. The region had reached out and grabbed us. It had drilled us into the sand, informing us that indeed we were still here. We had left in our minds to some all-night store where we could buy microwave burritos, and the desert said, Do not leave this place quite yet. Remember. Take the sand and sweet memory of water with you. Become thirsty and pained again before you go.

“We should put on our packs and start hiking out now,” Tom offered. I knew he was delirious. He'd been the one pushing the truck from behind, while I wore on the four-wheel drive from the cab. “We should get to the road and find a bigger truck to get us out.”

“No,” I said. “That's crazy. Not tonight. We should sleep. We'll go out tomorrow.”

We did not argue about it. We were too weary, so we went ahead and rocked the truck out of that hole and into another one. Sand sailed into the air. Back tires dug themselves a grave. We stopped for a minute. The darkness made the world empty around us, the headlights vanishing into the sky from our hole in the sand. I shut off the engine and headlights, got out and sat on the ground, Tom standing beside me looking at the stars, praying perhaps. With its hind wheels laid deep, the truck tilted upward like a sinking rowboat in an ocean too big to get out of tonight.

Even as the scent of burning clutch dissipated, the air did not smell of water. The water was ephemeral in the greatest sense. Since we started walking tonight we encountered no sign of it, we did not find its scent. It got farther away, first by miles, then by distances that could not be mentally crossed. Now it was gone.