Royal Arch Canyon, Grand Canyon

December

DARK.

Not the simple dark! that cradles you to sleep, but dark hard as stone.

I worked a knot by hand as rainwater shoved into my coat around my neck. I had to close my eyes with the rain poking up in the wind. I couldn't see anyhow. I wore a coat, boxer shorts, and boots without socks, trying to limit what would get wet. The wind came from seven directions at once, then joined and chimed up the cliff face, making a sound that screeched out of range. I finished the knot, checked the line. It was tight. Spare climbing gear had been used to get this tarp up, and the wind strained the moorings until they buzzed. I slipped underneath into shelter, and my partner Mike Morely's headlamp came on. The light was not for finding anything, or for seeing what gear might be left out, but just a reminder that we had light, that we were still in control. Our knees pressed together. Wind came under, sprayed our faces, then went elsewhere.

We were sitting on a ledge inside the Grand Canyon, where half an hour ago the air had been still and the sky, powdered with stars, said nothing of clouds. The ledge traced one of these monolithic cliffs of Redwall limestone, its edge rounded slightly, like a bowl lip, dropping into smooth walls below. We backed against a fifteen-foot boulder, crouching as far in as we could. If the storm had come during the day it might have been different. Our options would have been clear as we scurried around, battening gear down, looking up to see which way the storm moved, where the thickest parts lay. Instead we were blind and terrified for reasons neither of us could understand. It was no longer obvious how far our ledge extended. The storm had its thumb on us, grinding us into the rock. The tarp snapped up, then bunched down on our heads. Whip cracks came from each corner.

When the tarp kept snapping furiously, I shouted, “Jesus Christ!”

“I know,” Mike said.

“I mean Jesus Christ!”

He turned off his headlamp. We pushed closer together to keep as far from the edges of the tarp as possible. The first rock-fall came. It sounded from the north, a series of cracks and rumbles. The rain quickly washed out its echoes. Then something to the south. This one made the sound of a train derailing into the canyon, boulders uncoupling. We could hear each part, each shatter. A section of wall had come down. It bolted down the cliff, and again the rain took away any more details.

The desert is a book of change. Right now, pages fluttered too fast to read. Rocks are always falling in the Grand Canyon. I had become used to the sound, to turning suddenly during the day to see boulders chasing each other off the edge of an outcrop, to hearing the light clatter of small stones or pebbles falling from somewhere. A few Grand Canyon geologists have kept note of rockfalls, one writing that “the weakening process is a long one, and perhaps only a little extra heating on a hot day, or a light shower or a touch of frost may be the critical factor.” Tonight, everything was the critical factor. On a calm day, one of these geologists recorded thirty tons of Redwall limestone that he saw caving into the Colorado River west of here.

Boulders crumble to sand at the bottom of canyons. Intense rains wash the debris into even lower canyons. Everything is in motion. Sediment coming down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon was once, before Glen Canyon Dam, estimated to be 27 million tons passing a single point in one day.

All of this movement began here, on this night. Hard rain wedged itself into the cracks, pouring through holes and fissures, sending mud sailing over ledges. Events known as debris flows occur here, events now heavy on my mind. Of any place on this continent, the Grand Canyon has the greatest focus of debris flows, of monumental, sudden floods that dramatically alter the landscape. I did not mention to Mike how much I was thinking of them. Weak slopes in the canyon will fail, collapsing into floods below, which turn into a boiling mess of boulders and crushed shale. Rarely do large, stable cliffs like those of the Redwall fail. Debris flows generally come from the weaker formations, but the Redwall has certainly been known to collapse. We were hearing it clearly from beneath our whipping tarp. Canyons governed by debris flows are open toward the dominant paths of weather systems, which describes our canyon. They act as precipitation traps, gathering the confined, more intense storms.

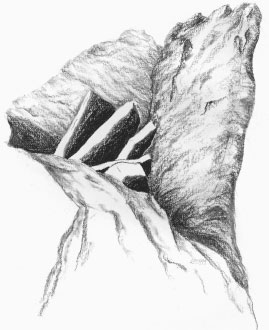

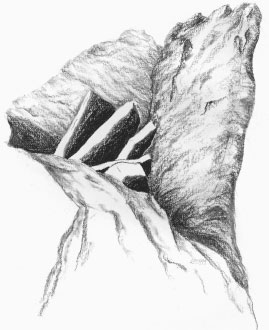

Not only is the direction of the canyons conducive to debris flows, but the actual constituents within the rock are primed to run. The sequence of formations in the Grand Canyon tends to be hard, sheer cliffs on top of weak shales on top of cliffs on top of shales. It is the shale of ancient oceans, as opposed to shale of prehistoric streams or estuaries, that best mobilizes debris flows. The shale crumbles, weakening the foundations beneath overlying walls, pulling down entire sections of cliff. The marine shales are heavy in the minerals illite and koalinite, which are basically lubricants, turning the contents of a debris flow into an oiled slurry, at the same time electrochemically bonding to increase the density of the mixture, allowing larger pieces of debris to remain afloat. Boulders become buoyant in this soup, traveling farther, quicker. Wherever these shales are exposed, debris flows are compounded. The Redwall limestone and its tiers of cliffs sit atop the Bright Angel shale, one of the heaviest in illite and koalinite. Directly overhead, barely breaching the rim of the Redwall, is the Supai Formation, a major source of boulders and weak ledges that supply the bulk in debris flows. Above that is the Hermit shale, the primary producer of lubricant minerals for these semi-liquid floods. Above that, Coconino sandstone cliffs lean over the weak Hermit shale, ready to fall. In between, we crouched on a ledge, listening to the collapse.

I have spent much time in places where if I wished to find water, I had to restrict myself to nothing but thoughts of water—not planning my life, not thinking of a job, a relationship, or a destination. I have walked between water holes not letting my mind slip once, remaining vigilant to any clue that might lead to water. And now, here, all I could think about again was water, but in a different way. I could not escape it. No other thought could possibly enter my mind. I backed to the boulder in fear of water bringing down the entire cliff, turning our bodies into debris.

Water-piled stones

Most historic debris flows in the Grand Canyon are associated with the hard precipitation of convective summer thunderstorms, which tend to be isolated and influence only one or two drainages at a time. In July 1984 a debris flow descended Monument Creek, west of here. The entire side of a canyon crashed down at about 160 feet per second. When it hit the floor, debris exploded 300 feet up the opposite wall. Boulders nine feet in diameter were washed to the river, several miles away.

Mike and I were now in a December storm, not the key time for debris flows, yet in December 1966 a forty-four-foot-tall wave of boulders and slurry descended Crystal Creek, on its way into the Colorado River. Cliffs had failed in numerous places, slumping into the flood. Fifty-ton boulders bounded for miles, finally wedging into the very bottom of the Grand Canyon. On that December day in 1966 they formed one of the largest rapids along the entire length of the Colorado River. It is now called Crystal Rapids, a Class X rapids, the most difficult rating that can be given in the Grand Canyon. Before this December flood, there was hardly a riffle in the same location.

I once talked with a geologist named Bob Webb, one of the principal researchers of desert debris flows. He had encountered one in the middle of the night where Prospect Canyon opens to the Colorado River. I asked what it sounded like. “Freight train,” he said. In a closet at his home he found a chart from that night's storm. He shuffled it out of its folder and pointed to a peak in a graph of rainfall. “You see that burst at the end? That's what you need to create a debris flow. And we felt that burst at camp because right around midnight our camp got blown to pieces by a high wind. Before I could get to sleep again I heard this big roaring sound.” The debris flow missed the camp and the twelve members of his research team by a couple hundred feet, rumbling down the floor of the canyon into the river. In the morning he walked to the river and stared aghast at the remains of the debris flow that created a massive new waterfall in Prospect Canyon and buried in boulders the left side of a rapids called Lava Falls.

I asked him if there had been any smell to it and he tapped the side of his head with his finger, his eyes sharpening as he remembered something in vivid detail. “It was kind of a salty, musky smell that comes from those kinds of flash floods…. I used to go out and measure flash floods on the Santa Cruz River [in southern Arizona] and it was the same kind of decaying vegetation, muddy water smell that you get.”

Mike and I were now at the source of such an event, should it come. We would be delivered to the river along with our camp and every surrounding stone. From beneath the tarp I listened to bursts of wind. They peaked and fell and peaked higher. The storm only grew. Mike told a story about an ocean voyage, then stopped talking. I prompted him to go on. He said that was all. So I asked him about climbing and about Yosemite, where he liked to travel. He started another story. This one elicited a monotone, each word given proper weight. Two summers ago he had finished a technical ascent of one of the big walls in Yosemite. Walking back with his climbing partner along a popular trail, he heard a crack and then a sound like a jet buzzing the valley. He looked up to see 170,000 tons of granite separating and falling from a cliff. I asked about the size of these pieces of cliff. He described them as a fleet of semitrailer trucks falling through the air, gently rotating as they descended.

When the boulders impacted the earth, the entire forest of pines catapulted, hurtling end over end. Mike hit the ground, held onto something. He was afraid he might asphyxiate in the blizzard of wind and granite dust that followed. He breathed through his clothes. When motion stopped, he crawled out of the dust. He and his partner were the first to arrive at the victims. One person was killed without question. Two young women were pinned beneath trees, partially crushed. He stayed with one woman, cleaning the blood, helping her with slow, calm words.

Then his story was over. He said he did not like times like this. He said that later this would make sense, in the telling of the story. But now, the earth was coming down around him. The basic footing of the planet was coming loose.

We talked our way through the storm, bolstering each other. We talked about fear and about how these things strengthen us. As we listened to rocks come down we talked about how we wished it would end, how the sun would rise and we would find ourselves alive. Eventually, amidst our talking and our silences, the wind slowed. The rain stopped abruptly, as it does when these storms suddenly change course or pass on. We both tentatively lifted our corners of the tarp and stepped into the night. Water could be heard washing down the cliffs.

We disassembled the shelter, shaking things out. Clouds left the sky as we reset our camp on the ledge. We were now gifted with a startlingly clear and calm night. I spread my bag on the flat ledge of limestone and crawled in. The night's element of consequence had been darkness. Now it was quietness. Water stopped running.

I waited with my eyes open, but there was nothing to wait for. How could I sleep? A clack of a single falling rock came from the north. I imagined it was no bigger than a drinking cup. But it was the only sound. I listened to it all the way down, each scrape and clip standing out as if speaking to me directly. It did not seem to fade as it fell hundreds of feet into the canyon.

Then silence.

Well into the 1930s it was believed that most erosion in the desert had little to do with water. Geologists cited extreme day and night temperature ranges and constant dryness, reporting that rocks must explode during the night from the pressures. They believed that it was the absence of water that caused desert erosion. In laboratory experiments, researchers tried to force rocks into cracking and exploding, assaulting them with temperatures and dryness far beyond what a desert could produce. The rocks did not budge. So they said that it was wind that had left deserts so chopped up with canyons and clefts. But when they hammered open these desert stones, ones gathered from the Mojave Desert in particular, they found hidden inside traces of moisture. Eventually they examined the shape of the land with increasing scrutiny. They walked the canyons. They witnessed floods and watched boulders roll away in the seething froth. Then they understood.

Desert floods come from rain. Most rain falling anywhere but in the desert comes slow enough that it is swallowed by the soil without comment. Desert rains, sporadic and powerful, tend to hit the ground, gather into floods, and disappear before the water can sink five inches into the ground. I have devised a simple experiment to explain this process. Find a curled, dried sponge under the sink and set it on the floor. Fill a glass with water and toss it, all at once, at the sponge. What you will get is water all over the kitchen floor. Now find another dry sponge. Fill the same glass with water and this time pour it slowly. The result will be obvious. The sponge is soaked, your floor relatively dry. Because of the intense nature of its storms, a desert receives rain most often as if from a tossed glass. The rain from the other night was not subtle and did not soak in. Water splashed off the desert and ran all over the surface, looking for the quickest way down. It was too swift for the ground to absorb. When water flows like this, it will not be clean tap water. It will be a gravy of debris, snatching everything it finds.

Walking alone along the canyon rim the next day, I picked through the results of these gravy flows from the night before. Agaves had been half-buried, muffled by six inches of smooth sand, while their blades poked up like birthday candles. Prickly pear cactus pads had the appearance of catcher's mitts, fielding the movement of rocks and sloughs of organic debris, straining oak leaves through their spines. Some were buried by small, square pieces of rock, remnants of Hermit shale and supai formation from above.

I gingerly lifted one of these remnant stones from a cactus pad. The rock stood white against all of the local red and maroon formations. It was Coconino sandstone, carried from several miles away. The cliffs up there are falling over each other, adding more and more material to these slopes, more sand to the river. Under certain rock formations you will sleep to the constant plucking of small rocks, pieces that whistle down and crack near your camp. The Coconino sandstone is particularly good at letting fly fractured arcs of rock, large enough to disturb you from your camp and send you elsewhere for the night.

Nearby I found in the sediment a single grayish black arrowhead. To its left, six feet away, was a small piece of broken pottery. I wheeled the potsherd between my fingers. It was not curved enough for a bowl or an actual pot. Maybe a dish, tan and glazed, seven hundred years old or so. I began counting pieces of pottery as I came to ten and then thirty of them.

A slight drainage another twenty feet away had dislodged—along with its usual fare of seeds, rock, and sand—numerous Anasazi potsherds. They gathered with debris of like size, caught in the feathered, sandy eddies, buried to their tips, or pushed sideways against a narrowleaf yucca. These were bluish corrugated pieces, the lips of jars, painted redware, bowl concavities, sherds with angular black-on-white paintings, smooth beige pieces, gray sherds with hand-drawn burnish marks, and the handle of a mug or of a water carrier.

In this exhibition of potsherds I found some that had been broken by mule deer hooves only days ago. The trail of water-driven pottery led to the remains of a round building, eighteen feet across. Pieces of pottery had fled from the structure in every downstream direction. It was an exodus. The potsherds were steadily on their way to the interior canyons, pushed by runoff.

I crouched and set one of these painted black-on-white pieces on my left knee. Typical of this culture's attention to detail, the lines of paint were as fine as shadows of grass blades. It occurred to me that a measure of a civilization should not be how well it stands, but how well it falls. In some places the water had stacked pieces on top of each other. They could have easily been mistaken for coin-size stones, gracefully blending with every other natural object being carried away.

I held the piece up so that it cut a shape against the sky. Behind it could be seen layers upon layers of cliffs leading into canyons, dropping then to innermost chasms, eventually to the river. The thread between these landforms was water, the downhill flow, the shape that scientists could not originally understand because, they asked themselves, how could a place defined by the absence of water be defined by the presence of it? Each object here at the rim was fodder. We were all being fed to the passage of water.