Class: Reptile

Order: Squamata

Family: Agamidae

Conservation status: Not listed

There’s no point in walking back. The only life I saw for the last million miles were the hypnotized bunnies and most of them are now wedged in the tyres.

Priscilla, Queen of the Desert

When I was eight I pinned a big map of Australia on the wall of my room. I decided that when I grew up I would live on a ranch half the size of England way out in the bush. Several decades have gone by since then and I still have not even visited the island continent. For all that I have actually seen with my own eyes Australia could be an elaborate fiction put together on a film set from pieces of Essex, southern California and New Guinea. But then there are the animals – creatures more fantastic than any found in bestiary or fairy tales. Nobody could have dreamt up the platypus or the kangaroo, still less the frill-necked lizard or the leafy sea dragon.

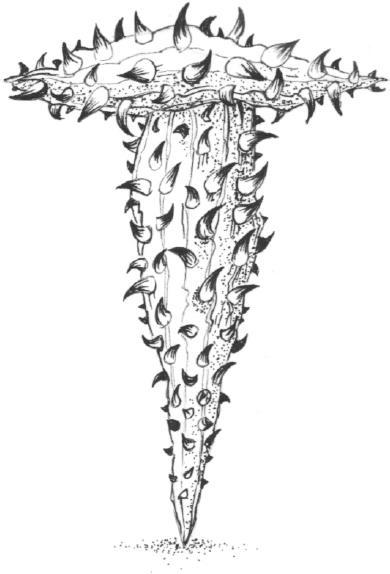

Adding to the fascination is the fact that such diverse and odd forms evolved in and around one of the harshest and most remote places on Earth where even non-indigenous species such as rabbits sometimes find it hard to get by. The Thorny Devil is a good example. This spiky lizard is one of the most remarkable Australian natives, although not in the way that its imported Latin name, Moloch horridus, suggests. (Moloch was a Canaanite god who in John Milton’s account was smeared with the blood of human sacrifice.) A typical full-grown Devil will fit on the palm on your hand and its densely packed spikes are no bigger than the thorns of a rose, albeit a particularly ferocious one. Picayune pricklius would be more like it. Not so much John Milton meets Ed Wood as Mark Twain meets Monty Python.

No, the Thorny Devil will not hurt a fly. Living as it does in the rough grass, bush and sandy desert that swathes much of Australia, it makes do with what there is, which happens to be ants. And this lizard is most partial to ants. It munches them as steadily as a moviegoer munches popcorn. (It would be nice to wander off here and celebrate the wonders of ants, a family of insects that have adapted to the most diverse and harsh environments on Earth. I’ll resist the temptation but not before mentioning one of my favourite ant-facts: some species are so small, and others so big, that the small ones could walk around inside the heads of the big ones.)

Ants may be delicious but you need something to wash them down with and the Thorny Devil has a neat trick for trapping water. Its body has ‘hygroscopic’ (moisture-attracting) grooves between the thorns on its skin, and such dew (and rare rain) as falls onto the animal or onto the grass through which it walks is taken by capillary action into these grooves. The Devil then works its jaw steadily to move water along the grooves which lead eventually to its mouth. Thorny Devils thus concentrate and drink dew. Analogous systems have evolved in other arid places. There is a kind of rhubarb that thrives, where little else does, in the Negev Desert, al Naqab, by similar means, and a Namib Desert beetle which captures tiny droplets in the rear legs that it waves in the air. Real-world adaptations are more ingenious than imaginary ones such as those sported by the Monopods, legendary dwarfish men whose likeness may be found on medieval world maps and who supposedly shaded themselves from the heat of the sun with a giant single foot.

The Thorny Devil itself is a tempting meal to those few larger animals eking out a living in this hot land, such as the occasional snake, goanna, buzzard or human. In its defence, the Devil has its thorns of course, and it may also tuck its head between its legs to present a potential predator with a false second head that usually rides on the back of its neck (making it, perhaps, lizard-kin to Denis Dimbleby Bagley in the 1989 film How to Get Ahead in Advertising). This false head can be bitten off without substantial harm to its bearer, and may eventually grow back. The Thorny Devil can also inflate its chest with air, like a Pufferfish of the desert: a harder prospect to swallow. But its best hope is to remain unseen in the first place and to this end the Devil, which is camouflaged in shades of brown and yellow, walks slowly and stops often, like a chameleon or a participant in a neverending game of grandmother’s footsteps.

There was a time when the Thorny Devil lived in a busier land. Until just a few tens of thousands of years ago Australia teemed with large creatures even stranger than the ones that so struck eighteenth-century Europeans. Isolated from other continents for millions of years, animal diversity here had taken its own course. Marsupials evolved to fill niches that elsewhere were taken by large placental mammals. One species of wombat grew as large as a hippopotamus. There was a tapir-like animal the size of a horse, and a kangaroo that grew to be three metres, or ten foot, tall. Some of the monotremes (egg-laying mammals) also ballooned: there was a platypus as big as a Labrador and an echidna as big as a sheep. And there were lizards of tremendous size and strength: Megalania was at least 3.5 m (12 ft) long and possibly as much as twice that. A 5 m (16 ft) land crocodile called Quinkana evolved long legs on which it could trot briskly after its prey, and hundreds of teeth that combined the properties of steak knives and meat hooks to tear them apart. A python 10 m (33 ft) long – perhaps the longest snake ever to have lived – preyed on all manner of animals but not, presumably, on a two-horned tortoise as big as a car. Giant flightless birds also stalked the land – real-world equivalents of creatures morphed by radiation to huge dimensions in B movies from the 1950s. At three metres tall and about half a tonne (1,100 lb), Stirton’s Thunder Bird was probably the largest bird ever to have lived. Bullockornis was a mere 2.5 m (8 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb), but it was a rapacious carnivore and has been nicknamed the Demon Duck of Doom.

Most of these beasts, along with others including another fifty or so species of giant marsupials, thrived until, between about 50,000 and 20,000 years ago, about 95 per cent of them went extinct. Exactly why this happened is debated. There may have been several factors at work, including natural climatic changes leading to drier conditions. But it is hard to avoid the conclusion that humans, spreading across Australia at just about that time, played a decisive role, and that they did so by causing great fires. The tough little Thorny Devil was among the 5 per cent that survived.

We are all familiar with fire’s potential to destroy but we are also accustomed to seeing it as an elemental and creative force. The Sun, which seems like fire, has long been treated in myths and religions as a cause or origin of life. In an Australian aboriginal story, for example, the Sun goddess Yhi first awakens plants and creatures into a silent world. And, of course, such stories have some relation to reality: all living things depend on a constant flow of energy from outside, and on Earth that flow derives overwhelmingly from the Sun (with a much smaller part from volcanic activity). Since ancient times, too, people have seen a kinship between Earthly fire and life. Thomas Browne, writing at the dawn of the scientific age in the 1650s, linked all three: ‘life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible sun within us’. Research over the following century showed that fire and life really were equivalent at the level of what could now be described as a chemical reaction. By the 1780s Antoine Lavoisier could write that fire is ‘a faithful picture of the operations of nature, at least for animals that breathe: one may therefore say with the ancients, that the torch of life is lighted at the moment the infant breathes for the first time, and is extinguished only on his death’. The contemporary science writer Oliver Morton summarizes some of the advances in understanding made in the twentieth century: ‘life is a flame with a memory’.

One of the surprising truths about actual rather than metaphorical fire on Earth is that it is a child of life, not the other way around. As was noted in Chapter 5, as far as we can tell, wildfires did not occur until about nine-tenths of the way into life’s existence on Earth to date when, some 420 million years ago during the Silurian, suitable terrestrial plant material was present under atmosphere concentrations of oxygen rich enough to create the right conditions for combustion. If, as has often been said, fire is like an animal, that is because, like animals, it feeds off life (specifically, plant material). Over the hundreds of millions of years since it first appeared, wildfire has become integrated into successive and different ecosystems. Huge fires raged in the great lycopod and tree fern forests that covered much of the land during the Carboniferous (359 to 299 million years ago), but these did not prevent the deposition over millions of years of vast amounts of unburned plant material, much of which turned into coal. In later ages, shrubs and trees and, in the last eight million years or so, grasses evolved to benefit from the release of nutrients occasioned by frequent but for the most part low-intensity fires. In Fire: A Brief History, the biologist Stephen Pyne refers to this grand sweep of pre-human history as ‘first fire’.

We may never discover exactly when man began to manipulate fire. One hypothesis says that our ancestors began to use it to cook food and protect themselves from night predators as long as 1.8 million years ago. Uncontested evidence, however, is no more than a few hundred thousand years old. But whenever it began, the human use of fire began our transformation into the dominant animal. And if man is ‘the cooking ape’ then it is more than food we cook. At some point, perhaps very early in the partnership with fire, our ancestors learned to start, and stop, bush fires in order to drive game and to produce succulent new growth. In doing so, they began to alter the ecology of entire landscapes. ‘In effect’, writes Pyne, ‘humans began to cook the earth. They reworked landscapes in their ecological forges.’ Later, perhaps, they harnessed fire to make new kinds of tools. From the fire-hardened spear-point to metalwork, from the combustion engine to the microchip: a hop, a skip and a jump. Taken together, these new uses of fire began to transform life on Earth as profoundly as did its original emergence. This is ‘second fire’.

The majority of the ancestors of the humans that we now think of as indigenous to other continents probably began to migrate out of Africa around 60,000 years ago. They were armed with ‘second fire’ and it is reasonable to suppose that successive generations burned large swathes of vegetation as they opened up new territories. By 40,000 years ago – some 800–1,000 generations later – people were living deep in the Australian interior. It may be that these early Australians burned the bush as enthusiastically and thoroughly as any landscape that humans had previously colonized or were to colonize later, but that, on this formerly isolated and exceptionally dry continent, the fires became more intense and widespread than almost anywhere else. As a result, most large herbivores rapidly lost their food supply and were driven to extinction along with the animals that preyed on them. Another possibility is that early Australians focused on hunting the big animals first and, with fewer herbivores to graze it, vegetation accumulated and became vulnerable to larger and more intense fires than those to which it was adapted. Whatever the precise causes were, the consequence was a sharp drop in the ecological productivity of the ecosystem: it probably diminished between ten and a hundredfold as many of its most efficient recyclers of nutrients were exterminated. Evidently, this was not sufficient to exterminate the Thorny Devil.

After the disappearance of most of the continent’s large animals, aboriginal Australians developed a practice known today as ‘fire-stick farming’. This involved burning relatively small areas of bush in low-intensity fires in such a way that kangaroos and other game were driven towards the hunters while, in the aftermath, nutrients released from the burned plant material fertilized the regrowth of edible plant species and attracted more game. Certainly, fire-stick farming was widespread on the continent at the time of European contact. ‘The natives were about, burning, burning, ever burning; one would think they were of the fabled salamander race, and lived on fire instead of water,’ wrote the nineteenth-century explorer Ernest Giles. Aboriginal Australians also set larger fires as a weapon against their enemies, as Native North Americans were also observed to do.

The climate in the parts of Australia where the Thorny Devil lives, characterized by great heat and drought and occasional heavy rains, is among of the most extreme on Earth. If humanity continues to burn fossil fuels as we do at present, the atmosphere is likely to heat by 4°C or more by 2070. As a result the climate in some regions of the world may be as hot and arid as those in Australia today. Others are likely to become wetter than they are now, as well as hotter. By the twenty-second and twenty-third century human life as we know it could become impossible in many parts of the tropics that are at present densely populated. Australia itself will face near stupendous challenges. Perhaps the Thorny Devil – unbelievably tough and adaptable, superbly engineered by nature to manage its most precious resource, water, effectively – can teach us a lesson or two.

There’s an old joke in which two Australians are marooned at sea in a small boat under a hot sun with nothing to drink. One of them finds a magic lamp in a locker and rubs it. A genie appears and says he will grant one wish. Without stopping to think the first Australian says, ‘turn the sea into beer’. Hey presto, the seawater turns into sparkling, cold beer. The genie vanishes. The two Australians look around, dumbfounded. Eventually, the second one speaks. ‘Well done, mate,’ he says; ‘now we’ll have to piss in the boat.’ Humanity’s job is to learn to see beyond a quick fix – to manage resources and environment so that we don’t sink under the weight of the mess we create. We need to not piss in the boat.