I’VE ALWAYS FOUND IT more than a little ironic that C. H. McGee chose “where nature did its best” to entice people to come to Seagrove Beach and despoil it. But McGee was no different from the other developers who were attracted to the natural beauty of the Redneck Riviera and, once there, set about erasing as much of it as they could.

When Peter Bos arrived in Destin in 1972, only a few years out of Cornell School of Hotel Administration and “searching for development opportunities,” he looked at the harbor and declared it “the singularly most beautiful piece of property” he had ever seen. For the next thirty years Bos built a career in the area. He took over and expanded Sandestin Golf and Beach Resort, developed marinas, built an upscale shopping mall that he called Destin Commons, and created Legendary Inc., a family of companies that gave him an interest in just about every sort of business on the coast. Among the properties he developed was HarborWalk Village, a collection of shops and restaurants anchored by the Emerald Grande Towers, “Destin’s only full-service resort.” Emerald Grande, in all its buff and burgundy glory, sat at the foot of the Destin Bridge, squarely in the middle of that “singularly most beautiful piece of property” that caught his eye in 1972, dwarfing the docks and dominating everything.

Bos’s Legendary operations may have been what Dewey Destin was referring to when he talked about “what you get when you exchange nature for economic well-being.” However, it must be said that Bos was no worse, and in some cases was better, than most when it came to preserving and protecting natural surroundings, though he did so in that well-established Florida tradition of making nature conform to what developers wanted it to be—whether what they wanted it to be was “natural” or not. The Emerald Grande was just that: grand, and colorful, and gaudy, and well appointed, and opulent (what else could you call a counter-top made of marble that the brochure boasted came from the same quarry that supplied the Paris Opera House?), and overwhelming—so tall that in some seasons it shaded parts of old Destin from dawn to dusk, like a sundial. So it was no surprise that Bos’s creation had more than its share of we-want-our-village-as-it-used-to-be critics. But Destin city manager Greg Kisela would have none of it. “Whether or not you like Emerald Grande,” he told the local press, “it has to be successful, because the harbor is our ticket. It is our past and our future.”

Emerald Grande dominating Destin Harbor, 2009. Photograph by the author.

The harbor was also where old and new Destin collided, and often both sides came out the worse for it. From the harbor the working charter boats went out in the morning and to the harbor they returned with fish on ice and gulls following behind. As the harbor developed, trendy restaurants came in and built decks where patrons could sit and eat and drink and watch the drama of the docks as the day’s catch was displayed and filleted. But some people on the restaurant decks eating and drinking and watching complained of the smell and of the noise, as though they thought fish would not smell fishy and gulls would quietly wait their turn for the heads and tails and backbones the deckhands threw into the water. So to cut down on the smell, clean up the harbor, and attract fewer birds, deckhands were told not to throw out the heads and tails and backbones for the crabs and gulls, but save them till the next day, when the smelly mess could be carried out and thrown into the Gulf to feed the fishes waiting there. One more inconvenience for the captains and crews, one more bit of old Destin that visitors would never know, fewer crabs under the docks, and, if there were a latter-day Rusty McHugh around, fewer backbones for the gumbo.

But nature was known to take revenge on those who pushed her too far. Build where you shouldn’t and a storm will get you, cut down trees or dig up vegetation and the soil will wash away, foul the water and there will be none for drinking or swimming, go into the Gulf when and where you shouldn’t and there could be trouble.

For some folks the Gulf was trouble anyway. Those who came to the beach to play on the sand and in the surf loved it. Others didn’t. Salt water burned their eyes, sand made them itch and chafe, seaweed got into their swimsuits, jellyfish stung them, red tide clogged their sinuses, and there were sharks. Those people sat by the pool and enjoyed the sun, played golf, shopped, ate, and then went home to tell folks how great the “beach” was. In some regards the nonbeachloving beachgoers had a point. At times the beach could be less than what the tourist development councils advertised. Yes the Gulf was salty, the sand was sandy, and the water wasn’t always clear, especially in early summer if there was a June grass invasion. The slimy stuff would appear offshore one morning, a dark patch that slowly drifted in to foul swimming areas and turned the surf into a green soup, until it washed up on shore to rot and stink. Year-round and summer-long residents complained like everyone else, but they knew that what collected on the coast would anchor the sand that eventually covered it and help the beach withstand future storms. They laughed when Seaside, to keep its beach clean for its homeowners and guests, scraped up the grass, for they knew that when September gales battered the shore, Seaside’s beach would erode more than its neighbors—and they were right. But if you were down for the one week that you had saved for, planned for, longed for, green slimy water and stinky beaches were not part of the package you ordered.

Then there were sea creatures, such as jellyfish that appeared in the water to sting tourists and convince little children that the pool was where they should play. No telling how many of the people who like the coast but don’t like the beach feel the way they do because at an early age they were stung and never forgot it.

And there were sharks.

Everyone knew, or should have known, that sharks were out there. The Gulf was their home. A tourist could, and often did, stand on the balcony of their upper-floor condo, look out at the clear, emerald green water and see the long, slim cylinders, lined up like submerged logs, between the first and second sandbar, about one hundred or so yards out. They could watch swimmers unknowingly approach and could see the cylinders, alive now, with a gentle motion of the tail, ease away, for most of the time sharks were no more interested in swimmers than swimmers were in sharks. However, over the years, as more people came to the beach, more people invaded the sharks’ habitat, and the chance of an encounter increased.

Then, in the summer of 2005, a shark attacked and killed a fourteen-year-old girl off Miramar Beach in Walton County, just east of Destin. Two days later a sixteen-year-old boy was attacked and badly bitten when he was fishing in waist-deep water off Cape San Blas down the coast from Panama City. In both cases there were extenuating circumstances—the girl was around two hundred yards off shore and the shiny jewelry she was wearing may have attracted her attacker. The boy was reeling in a fish and the struggling catch may have drawn the shark to him. But for the families of the children, extenuating circumstances did not matter. After those incidents helicopters began flying along the coast looking for sharks and when they saw them, the pilot circled round to let folks along the beach know. The precaution worked. Reports of shark attacks declined, and when they did, flights were cut back until they were needed again—which for someone might be too late.

Then there were the mice.

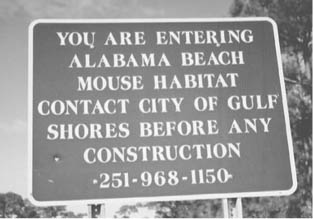

As early as 1984, the Mobile Press-Register reported that down on the coast some “condo developers had to deal with controversies over construction on the sand dune line and the plight of the nearly extinct beach mouse.” At that point it is unlikely that many people knew there was such a thing as a beach mouse, much less that it was “nearly extinct.” So when “federal officials moved in to rescue the mouse from the bulldozers and managed to remove a few of the nocturnal creatures” before site preparation began, most folks thought that was a reasonable solution. However, the next year the Alabama Beach Mouse was put on the federal endangered species list. Soon after that it was joined by the Perdido Beach Mouse, and the stage was set for future conflicts. No longer would it be acceptable to simply rescue the beach mice from the bulldozers—if you could catch them. The rodent was federally protected, which meant its habitat, the place where builders wanted to build, was protected as well.

Although some who had seen the mice described them as “precious little animals,” scientists considered beach mice important for more than their aesthetic appeal. Researchers pointed to the mouse’s “dwindling population as a signal of the decline of the Gulf coast’s natural environment.” As long as there were mice around to “emerge from the sand dunes at night to munch on sea oats” and scatter the seeds, it meant that the coastal ecosystem was healthy and the natural balance was in place. The loss of the beach mouse habitat and the subsequent loss of the beach mice meant “the entire coastal ecosystem has moved closer to death.”

So the battle line was drawn. On one side were environmentalists who wanted to save the mouse and with it the natural beach. On the other side were developers who either couldn’t have cared less about the mouse or felt they had done all that could be reasonably expected to protect the rodent and its habitat and intended to do no more.

In the late 1990s the environmentalists got an ally. Out on Fort Morgan Road residents and vacation cottage owners rose in protest when they learned of plans for the Beach Club, a “massive” development that, according to the Mobile Press-Register, was “being built untouched by local zoning.” These folks joined with the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth and together they sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Department of the Interior on the grounds that the permit granted to developers violated the Endangered Species Act and threatened the habitat of the beach mouse. “Condominiums are not in short supply on the Alabama coast,” environmentalists and their supporters argued, “but native species are.” To the dismay of developers, a federal judge agreed, more or less. In June 2002, the judge ruled that the permit to build had been granted without a full assessment of the impact the development would have on the beach mouse habitat. Though there were appeals, the immediate effect was that at least one developer stopped developing.

Down on the other end of Pleasure Island another controversy was brewing, and the mouse was about to find itself at the center of this one as well. Now there are few things that the folks who put the “redneck” in the Redneck Riviera valued more than their boats. Whether built for speed or fishing or both, whether used on the Intracoastal Waterway, taken back into the creeks and marshes, or powered out into the Gulf, the boats were lovingly maintained and treated with respect. But boats need water, and since most owners did not have a dock of their own, they depended on public ramps—the common man’s marina.

Beach Mouse habitat sign, Fort Morgan Road, Alabama. Photograph by the author.

The Orange Beach public ramp was especially popular. However, parking was limited, so when the weather warmed and boaters arrived, trucks and trailers spilled out of the lot and onto the shoulders of the road. Neighbors complained about the noise and the traffic. Boaters complained about the inconvenience. But the city had a solution: at the east end of the town Orange Beach owned a vacant plot of waterfront land with access to the pass that led into the Gulf. It was just big enough for a ramp, a parking lot, and restroom facilities. So the city decided to build a second ramp there, and in the summer of 2007, officials unveiled their plans.

It seemed a perfect solution. Only it wasn’t—at least not to owners of upscale condos nearby and to the folks with homes on Ono Island, which was right across from the proposed ramp. They protested to the city council that the noise from the rednecks and their boats would take away from their peace and tranquility and spoil their quality of life. The city council was aware that most condo and Ono owners were not residents (and therefore did not vote), whereas many of the boaters lived in town, so plans for the ramp went ahead.

Opponents tried another tactic—stop the ramp to save the beach mouse. If a mouse could halt work on the Fort Morgan development, the opposition reasoned, it could stop the Orange Beach ramp.

Although the folks on Ono and in the condos had previously shown little if any interest in saving the beach mouse, overnight they became advocates for the endangered rodent. To help them in their crusade they brought in environmentalists who they were sure would be their allies. Only they weren’t. When environmentalists appeared before the city council they testified that while the property was prime beach mouse habitat, building a ramp wouldn’t endanger any mice because there were no beach mice where the ramp was to be built. Surprised but undeterred, the condo/Ono alliance announced that since the place was so perfect for a mouse colony, they would catch some mice at another location and turn them loose on the proposed site. This had been done in the past, when beach mice were taken from Gulf State Park and used to repopulate public lands over the line in Florida. Why not do it again?

Because, said the environmentalists, the feral cats would eat them, just as feral cats had eaten the mice that once were there. The mice couldn’t be restored until the cats were gone.

Feral cats had been a problem for native species for some time, but this particular cat population had a specific origin. A while back someone had pointed out to the person planning a condo nearby that he might have trouble getting the necessary permits because there were beach mice on the property. Not to worry, said the developer. He went down to the local animal shelter, adopted some cats, and turned them loose. That solved the beach mouse problem and put a cat problem in its place.

In time some local women started feeding the cats (being out of mice to eat, they were hungry). These women were as determined to protect the cats as environmentalists were determined to protect the mice. Hoping to satisfy the cat feeders, the condo/Ono coalition hired a professional trapper to humanely trap the cats, move them to another location, and open the land for the mice. But when the trapper trapped a cat that was not feral, the owner was outraged, and the controversy continued.

It continues still. As yet, no ramp has been built.

Meanwhile, off to the east, along the “Beaches of South Walton” another clash between environmentalists and beachgoers was brewing, this one over toys, tents, and turtles.

Sea turtles of various types—green turtles, leatherbacks, and logger-heads—had been coming ashore since forever, from late spring through summer, to lay their eggs. Not many people ever saw them. They came ashore at night, struggled across the sand to the selected spot, dug their nests, deposited their burden, covered it over, and returned to the Gulf. The next day you could see the trails they had left, and if you knew where to look you could find the eggs, soft and rubbery and just the right size for a rolling-race down the dunes, a game beach children played years ago, before they knew any better. The turtles faced other dangers as well. Residents recall being on the beach at night and occasionally seeing a nesting turtle. Then, hearing a rustling among the sea oats in the dunes, they shined their flashlight toward the sound and saw the glow of eyes—raccoons, lined up waiting for their feast.

And there were the toys, tents, and chairs. If a turtle came on shore and bumped into an obstruction while seeking a place to nest, she might get discouraged, turn around, and go back into the Gulf where she would deposit her eggs to be eaten or to rot. And there were lights. As the coast developed and added brightly lit motels and amusements, people began seeing tiny, perfectly formed turtle hatchlings, smashed flat on the highway, run over as they crawled toward the glow they thought was the moon over the Gulf, which instinct said would guide them to the water. Heading into the Gulf could be dangerous as well. Between nest and water there were ghost crabs and birds, while waiting in the waves were all sorts of creatures who just loved to eat little turtles.

So the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service recommended that sea turtles be put on the endangered species list. But even before the listing, there were folks along the Gulf who wanted to protect the turtles, and they settled on a two-part mission. First, something needed to be done to give the nesting turtles an unobstructed beach, and second, the lights that attracted hatchlings inland needed to be dimmed or extinguished. Both proposals ran directly counter to long-standing beach traditions.

First, the unobstructed beach.

Turtle nesting season and the summer tourist season were the same. For years it had been customary for beachgoers to carry a lot of “stuff” to the beach and leave it there overnight to be used the next day. They would put up a tent or umbrella and surround it with chairs, toys, and coolers, creating a kind of outdoor rumpus room. At the end of the day, rather than take their stuff back up the stairs and over the dunes to the place where they would spend the night, they left it. No one ever stole it. The worst that might happen would be that someone would borrow a chair to watch the moon rise, and those folks would usually put it back where they found it. It was an honor system and generally it worked. At the end of the day some folks would take down the tent in case a storm came up and pile the stuff neatly inside the frame, but others would just leave everything scattered about. Why worry? There wasn’t much happening on the beach at night. Unless you were a turtle.

For turtles, night was a busy time. As early as 1995, environmentalists along the Redneck Riviera were telling anyone who would listen that the stuff left on the beach was getting in the way of turtle nesting and threatening the survival of the species. So naturally talk began about requiring people who brought stuff to the beach to take it off the beach at night.

Some people didn’t like that. Taking stuff away was difficult, inconvenient, and just not the way things had been done all these years. One local noted that maybe it would be best for the breed if the turtles that were too dumb to find a way around a tent pole or chair were weeded out, while the turtles that could figure out the problem survived—survival of the fittest would make the species stronger. But “turtle people,” as the less zealous called the more zealous, would have none of that. The debate raged, more or less, until 2007, when the “turtle people,” who were by then organized as TurtleWatch, got the Walton County Tourist Development Council to begin a campaign called “remove it or lose it.” This tactic seemed to satisfy federal requirements to protect an endangered species, but the effort upset folks who did not want to leave their stuff on the beach at sunset and come down the next morning to find it gone.

Now to be fair, sheriff’s deputies who were sent out to enforce the new code did not take the stuff away at first. Instead they tagged it with a warning telling owners that if anything interfering with “beach maintenance, nesting turtles, or emergency vehicles” was left on the beach another night, code enforcers would take the stuff away the next day. Many folks, not believing this could happen, tore up the tag and left their stuff. When they returned in the morning, the beach was clean. According to David Sell, TDC beach management director, “the first year (2007), it was unbelievable. We were removing a dumpster a day.” Word got out and the next year “it was about a dumpster every three or four days.” But with no way to recover what was lost, tourists and those who rented to them were angry and ready to go to court.

Meanwhile, the county commission got into the act and passed an ordinance that was supposed to fill a legal loophole and put more authority behind enforcement. The ordinance said, in effect, that you had to have a permit to leave things on the beach overnight, but even with a permit if what you left would “obstruct, hinder, or otherwise impede” evening activities by government employees or turtles, your stuff would be removed. The county commissioners were convinced that this revision addressed all objections.

The county commissioners were wrong.

When code enforcers came onto the beach that was claimed by Edgewater Condominiums and took away some items there, the condo filed suit. As far as Edgewater’s condo association president was concerned the code was “part of a growing trend toward over regulation by the county” and she and the association’s attorney complained of the “growing encroachment” of the county on private land. The condo argued that requiring a permit to keep items on what it claimed was condo property was “unconstitutional” and wondered why the county required permits when the EPA and the Corps of Engineers did not. Meanwhile, regular folks who did not want to lug their stuff home every night began pulling it back and putting it under the county maintained stairs leading down to the beach. They figured that if the stairs did not obstruct the turtles or vehicles on official business, the stuff under the stairs wouldn’t obstruct them either. The signs that appeared at access points to the beach told beachgoers how to get to the beach, where to throw their trash, the dangers they faced in the water, the things they could not do on the beach, and whom to thank for all this information. What the signs did not tell beachgoers was that they could not store their stuff under the stairs, so beachgoers figured that they could.

Turned out they couldn’t. Enforcers carted it off anyway.

As the controversy swirled around them the county commissioners voted to change the in-your-face “Remove It or Lose It” slogan to the kinder, gentler “Leave No Trace.” However the friendlier name did not change the enforcement and those who got their stuff taken away by the dawn’s early light were not happy.

In the summer of 2008, all this came to a head, when what seemed like half of the town of Puckett, Mississippi—“home of three hundred wonderful people and a few old grouches”—made their annual trek to the beach. They rented houses and condos and settled in for a week of fun in the sun. In class and character Puckettians were direct descendents of the people who came to the coast after the Second World War and for whom, rightly or not, the Redneck Riviera was named. As they had in years past, they covered the sand with all manner of obstructions—tents and coolers and chairs and toys—and left them overnight. The county enforcement folks came, picked up the Puckett stuff and carried it away. Irate phone calls followed and as the threats never to return cascaded upon the folks who were just doing their jobs and the officials who told them to do it, county commissioners and TDC planners began to wonder how they could get out of the mess they were in.

Beachgoers from Puckett, Mississippi, with assorted friends, summer 2009. Photograph by Walter Lydick.

The mess got worse. A new sheriff took office and announced that “he did not see enforcement of county ordinances as a proper role for sheriff’s office personnel” who had their hands full with the crimes that he felt were more important than tagging tents. Then word spread that if you had some old busted coolers and broken chairs, just pile them on the beach and the county would take them away for free. In the midst of all of this, someone went down after the enforcers completed their morning rounds and took pictures of the ruts made by the vehicles they drove along the beach to pick up the stuff. The pictures were published in the local newspaper, with a caption pointing out that the ruts were so deep that they were a bigger obstruction to nesting turtles than tents and toys.

Critics had a field day. They gleefully noted that in an effort to kowtow to the federal government (a major sin in some coastal quarters) and make the “turtle people” happy, county commissioners had passed an ordinance that made matters worse for everyone and everything. The Walton County regulations told folks that they could not leave their stuff on the beach overnight because it would obstruct emergency vehicles that seldom came to the beach at night. The rules said folks could not leave their stuff on the beach overnight because it might hinder beach maintenance even though no one came out to maintain the beach in the dark. The county sent out enforcement vehicles that made ruts that were bigger hazards to turtles than they stuff they came to carry away. It was ridiculous. Everyone lost. Even the turtles.

Now no one was for killing turtles. (Even my friend who volunteered to eat at any restaurant that would serve turtle soup was kidding—I think.) However, to opponents of the ordinances this was just one more case of government trying to prevent people from enjoying the sand and the water the way they always had. These dissenters held to a fundamental belief, nurtured by years of uninterrupted activity, that the beach belonged to everyone, which meant that it belonged to no one—not turtles, not mice, not condos or hotels, not the guy who claims to own beachfront property, and most of all, not to the government. To these folks, they themselves were as much a part of the natural environment as sea oats and dunes, so to limit their activities or cause them inconvenience just for the sake of a turtle or two—well, it wasn’t right. And when a condo successfully sued the county for coming on its “private” beach and confiscating a volleyball net, and was allowed to keep the net up, longtime beachgoers wondered who would sue the county on their behalf.

The answer, of course, was “no one,” so while the sheriff’s department and the TDC’s beach maintenance crews argued over whose responsibility it was to tag and confiscate the stuff, beachgoers adapted to the new rules. Seeing that at the end of the day the businesses that rented out umbrellas and chairs to the more affluent tourists folded up their stuff and took it back to the foot of the dunes and away from the county stairs, the not-so-affluent who brought their own chairs and umbrellas concluded that if they did the same whoever was sent out to make ruts and confiscate would leave their stuff alone. And it worked. The beach maintenance folks who greeted the dawn doing what they were told to do must have thought that it was a logical compromise. Besides, the enforcers and the enforced are cut pretty much from the same cloth. Just a bunch of hardworking, decent folks, some trying to have some fun, some trying to make a living, neither wanting to cause the other any trouble.

As for the turtle people, they pointed out, with some logic, that “it does not make a difference to a sea turtle whether it is private or public property, it is their sea turtle nesting habitat” and they will try to use it. As for the “pull it back” compromise, they pointed out that sea turtles nest “anywhere on the beach—not just to the toe of the dune,” so even leaving stuff that far back “seemed like a bad practice.”

Maybe it was, but before long the argument shifted once again and protecting the turtles became more than a matter of toys and tents on the beach.

In July 2008, the Panama City News Herald reported that the “Bay County Tourist Development Council adopted a draft ordinance restricting manmade lighting along the beach to protect endangered turtle hatchlings.”

As has already been pointed out, for years anyone paying attention knew that turtle hatchlings emerged from eggs and sand, saw the city lights, and headed inland, where they were flattened as they tried to cross the road. But now the federal government, with the Endangered Species Act in hand, was telling counties and communities that if local governments wouldn’t adopt appropriate lighting standards then the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would stop helping rebuild storm-damaged beaches. This caught the officials between a rock and a hard place. The beach was their moneymaker. It was what drew most tourists to the coast. After the storms of 2004 and 2005, they needed the Corps to keep the strand wide and pretty. Although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service assured beachfront residents that while “lighting is one of the greatest threats to sea turtles on land [it] is the easiest and most affordable to correct,” folks living and working on the coast were not so sure. Retrofitting or removing the hotel, motel, condo, and parking lot lights for the sake of turtles promised to be troublesome, expensive, and an enforcement nightmare. But it had to be done.

So the Bay County TDC drew up an ordinance—eleven pages of rules, regulations, suggestions, and exceptions. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service made changes, and when those were accepted, the federal agency endorsed it. Then it went to the Panama City Beach City Council and the county commission, where it was debated as “a work in progress” and finally passed. But even though TurtleWatch got a government grant to purchase “sea turtle lights” and distribute them free to beachfront property owners, replacing prohibited lights was slow going. That too was a work in progress.

The debate over turtles, tents, toys, and lights was yet another example of what was becoming an increasingly common complaint along the coast—that the overregulation of individuals and institutions was spoiling the beach for everyone. It was what citizens who opposed the incorporation of Gulf Shores, Destin, Panama City Beach, and points in between had predicted would happen, and now they were saying “we told you so.” But it was the price those who favored incorporation were willing to pay for police protection, street maintenance, water, sewers, and schools—all those things that attracted businesses and buyers, tourists and investors. The line between the two positions was becoming clear, and both sides were spoiling for a fight.