SO WE GET BACK to where it all began, back to the beach, to what the Miami Herald called Florida’s “signature attraction.” Even if there were no golf, no amusements, no recreational eating or shopping, no fishing, no Flora-Bamas, no Seasides or Sandestins, folks would still come to Florida for the beach. And if tourist industry figures are to be believed, the beach is also why they come to south Alabama.

However, as we have seen more than once, some folks figured that they had the right to keep people off the part of the “attraction” they claimed was theirs. Others contended that they couldn’t, not legally anyway. So it followed that late in 2009, a case was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court that promised to determine, once and for all, whether or not an individual could “own” the beach and, by owning it could bar others from it. If the Court decided such private ownership was not permitted, then the state’s “signature attraction” belonged to the public, and the state could maintain it for public use.

The whole thing focused on “nourishment”—the rebuilding of eroded beaches by the state. The process was not new. Back in 1922, New York’s Coney Island was washing away so officials pumped in sand to enhance the shore. Since that time there had been over three hundred major beach nourishments around the country. Not surprisingly, Florida, with its 825 miles of coastline, had the most of these projects—140. Thirty-five of Florida’s sixty-seven counties used taxpayer money to build up their beaches. And under Florida law, a beach created with public money belongs to the public.

Some folks had no problem with this. Down the coast, near St. Petersburg, the city manager of Belleair Beach told the St. Petersburg Times that residents there “love beach renourishment.” Living near some of the most heavily eroded and frequently nourished beaches in the country, residents of Belleair and their neighbors agreed with local realtors that beaches not only protected beachfront property, they increased its value. Better to have “a big, wide beach behind you, instead of having water coming right up to the seawall,” one real estate agent noted. However, there was a catch. According to state senator Dennis Jones, who represented the stretch of the coast where Bellaire Beach was located, “if the public pays to restore a beach, they should have the right to access it.” Jones, who got the nickname “Mr. Sandman” for his ongoing efforts to nourish the beaches in his district, saw it as a quid pro quo arrangement. The state enhances and protects beachfront property at public expense, and in return beachfront property owners allow the public access to the state-created beach.

However, there were some beachfront property owners who said they would rather “opt out” of nourishment and have a private beach, even if it was eroded, than have a beach that was broad, wide, and public. But it was not that simple. Beachfront owners received public support in ways that went beyond nourishment. Most had their property insured under state and federal programs that were subsidized by taxpayers. Nourishment supporters accused owners of wanting to reject the very thing that not only protected their property but also kept insurance premiums at least a little lower for the folks subsidizing them. Then there was the matter of state-and federal-built roads and bridges that had allowed developers to develop beaches that homeowners now claimed were private. In other words, it could be argued, and was argued, that the public made it possible for beach-front owners to live on the beach and therefore the public had a right to sit on the sand, nourished or not.

But was opting out even possible? The beach moved and engineers said that if one owner nourished and that owner’s neighbor did not, sand from the rebuilt beach would eventually drift next door. As a result the unnourished owner got public sand from the nourished neighbor. The “opt-out” replied that this was part of the natural process, however the public was quick to point out that nature had been altered by nourishment and the unnourished were benefitting from it.

Seaside’s nourished beach after Hurricane Opal. Initially homeowners were told that there would be no residential construction south of Scenic Highway 30-A, but like so much of Seaside’s initial plan, that changed. Photograph by the author.

Then there was the question of protecting the coast as a whole, which Florida claimed was its responsibility. An opt-out beach leaves an eroded gap in the nourished shoreline, and while that space might be filled in by the natural movement of the sand, it might also accelerate erosion for neighbors. So it would seem that it was the duty of the state to maintain something of a regular shoreline so everyone would be protected, and therefore opting out could not be allowed. But if no one were allowed to opt out, and if the government nourished the beach and declared it public, would beach-front owners be due compensation for what was “taken” from them—their beachfront? Most observers agreed that the state did not have the money to buy up the beaches of Florida, even if taxpayers wanted it to, and many did not. The cost of restoring alone was at times hotly debated—inland politicians argued that their constituents should not have to pay to protect and insure places where people should have never built in the first place—Destin’s Holiday Isle, for example. The state’s buying the beach was not an option.

Then there was the legal principle of “customary use,” which held that beaches that had been customarily, traditionally used by the public long before there were beachfront owners to claim them could be used by the public still. Did Florida beaches fall into this category?

It was, most everyone agreed, a mess. Most everyone also agreed that if it was resolved in favor of the beachfront owners who wanted to opt out, everything from property values to insurance rates to the state’s $65 billion tourist industry would be affected. As Senator Jones summed it up, ending the beach nourishment program would “have a crippling effect on Florida’s economy.” Even so, opt-out beachfront owners and their supporters argued that the very idea that a state could “take” private property for whatever reason, to protect whatever interests, without just compensation for the owners, violated what they felt was one of the most fundamental rights of American citizens—the right to own property, protect that property, and use that property as they saw fit.

With compromise out of the question, a judicial decision appeared the only way to resolve these differences, or to at least declare that one side was “right” and the other “wrong,” that one “wins” and the other “loses.” So the case of six Destin beachfront property owners went before the U.S. Supreme Court, where eight justices listened to attorneys argue that the plaintiffs’ property rights should extend all the way to the water, or at least the mean high-tide line, no matter who pumped sand onto the shore. (Justice John Paul Stevens, who owned a condo in Fort Lauderdale, sat this one out.) Those attorneys contended that back in 2003, when Destin, Walton County, and the state added sand to create a seventy-five-foot-wide public beach, the state took away their clients’ “ability to own, possess and exclude persons” from what they claimed was theirs. As a result “commercial vendors” were setting up on land that their clients should be able to control. As one of the owners put it, the case was about “heavy-handed government actions that eliminated private property rights without either consent or compensation.”

Lawyers for the state argued that the state’s responsibility for protecting the public and its resources justified nourishment, that a nourished beach paid for by the public should be open to the public, and that the principle of “customary usage” allowed people to use the beach whether it was nourished or not. They also pointed out that if the Court ruled for the property owners “we’d be in the position of paying private property owners to put sand back in their yards.” In the questioning that followed, Justice Antonin Scalia raised the point that rather than “taking” from the property owners, the state was actually giving the owners something and wondered if the additional beach and the protection it afforded might be “sufficient compensation” for what the owners claimed was “taken.” Other justices asked the lawyers questions about who owns the sand that accumulates naturally and whether the state could build a beach just to attract students on Spring Break.

And when the day was done, the justices went into their chambers and the two sides waited for a ruling.

Meanwhile, back down on the Gulf, nature was not waiting. Beaches on the western end of Holiday Isle were washing away. For home and condo owners there, nourishment was not an issue. They wanted sand and wanted it so desperately that the strings attached did not matter. Their argument was not with the government or the public it represented. Their argument was with property owners across the pass on Okaloosa Island. At issue was the question of where the sand to nourish the eroded beach should come from and who should pay the bill.

As we have seen, for years the Gulf side of Holiday Isle, across from Destin Harbor, had had problems with erosion. The issue became critical in 2009 when Tropical Storm Claudette took away so much sand that Florida governor Charlie Crist visited Destin, surveyed the damage, and declared, “We’ve got to have some beach reconstruction, that’s very clear to me.” But saying was one thing, acting was another, and before the city could get the necessary permits and approvals, a second tropical storm, Ida, hit. Ida washed away more sand, eroded foundations, and caused some structures to collapse. Conservative estimates set the cost of the damages at $500,000. “This shouldn’t have happened,” a member of a Holiday Isle homeowners association told the press. “We’ve never had any beach restoration down here, and until we do we’ll just keep getting beat up by storm after storm.”

A plan to restore and nourish Destin (including Holiday Isle) and Okaloosa Island beaches was in the works when some Okaloosa Island homeowners who didn’t want to participate filed suit. Their position was much like that of the opt-out beachfront owners in Destin, but they were also upset about the quality and color of the sand being brought in and felt the special assessment levied on beachfront owners to pay a portion of the $20 million project was unfairly calculated. Moreover, as far as the Okaloosa litigants were concerned, their beach did not need nourishing, so they wanted their island to be taken out of the restoration plan.

It was true that Okaloosa Island did not have the erosion problems being experienced by Holiday Isle. According to one homeowner there, Tropical Storm Ida actually added beach to their property. As far as they were concerned, Holiday Isle should solve its own problem. And what a problem it was. According to one estimate it would take a line of dump trucks eighty-five miles long to carry the 200,000 to 300,000 cubic yards of sand needed to restore the island beaches. That was a lot of trucks, which would mean a lot of noise and a lot of congestion—a lot of all the things people came to the beach to avoid. Wasn’t there a better way? many wanted to know.

There was: the sand could be pumped in.

As luck would have it, at that very moment the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was getting ready to dredge the pass between Holiday Isle and Okaloosa Island, the pass that led into Destin’s famous harbor. Since most coastal engineers believed that the beaches migrated from east to west, the sand in the pass had washed in from eroded Holiday Isle. So Holiday Isle folks suggested, why not put the sand back. The pass would be cleared, Holiday Isle would be renourished, and the cost would be considerably less than anticipated. It looked like a win-win situation for everyone.

Of course it wasn’t. Even though those involved weren’t traditional rednecks, the good old boy and girl belief that “what is mine is mine and you’d better not mess with it” still permeated the region. Residents of Okaloosa Island, already upset over the cost and execution of nourishing plans, rose in protest. The sand in the pass might have come from Holiday Isle, they said, but it had been heading for Okaloosa Island before jetties and the pass cut it off. Okaloosa Island may have enough sand now, they argued, but there was nothing to guarantee that it would in the future. Therefore, the dredged sand should be placed on Okaloosa Island, where it was going, instead of Holiday Isle, from whence it came. The Okaloosa point was simple—if Holiday Isle got Okaloosa sand then one day Okaloosa would erode and need nourishment, which they were on record opposing. As one Okaloosa resident put it, “Holiday Isle’s scheme to fix their homes involves destroying ours.”

Meanwhile, there was a pass that needed to be dredged, and unless it was, and soon, shoals would build up and Destin’s fishing boats would not be able to get out into the Gulf. Some saw this as an unfortunate consequence of the controversy. Others understood that it was part of the strategy by Okaloosa homeowners to get the sand put where they wanted it put. Until they got their way the Okaloosa group talked of “holding the harbor hostage” with lawsuit after lawsuit. It was another mess, but for the moment at least it was a local mess. However, if the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of beachfront property owners in the Destin case, the Okaloosa Island–Holiday Isle controversy would become part of the bigger picture.

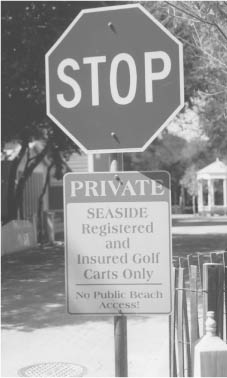

Seaside signs denying neighbors unrestricted access to the town and its beach. This is a much-less-intrusive announcement than the one that first appeared—it does not block the street. Photograph by the author.

Then there was Seaside, where the question of beach ownership and access turned into a controversy uniquely its own. And why not, for Seaside was unique. A gated community without gates, upscale and exclusive, yet welcoming to all. A good neighbor to those next door who came and went in and out of Seaside almost as if they lived there. Folks from Seagrove and WaterColor walked from their beach to Seaside’s beach, then up Seaside’s stairs to Seaside’s shops. They biked or rode golf carts into the town center to attend concerts and eat at the restaurants and cafes. They liked Seaside. Then in the spring of 2007, signs appeared on the beach boundaries between Seaside and Seagrove on the east and between Seaside and WaterColor on the west. PRIVATE they read, NO PUBLIC ACCESS. In smaller print was added, “Pavilion Use and Beach Access Strictly Limited to Homeowners and their Guests.” And at the bottom, in bold letters again, it warned SECURITY ENFORCED. Similar signs appeared at the roadside entries to Seaside’s beach walkovers. The community had cordoned off its beach with signs.

Signs also appeared in the middle of streets leading from Highway 30-A into Seaside’s neighborhoods warning those who came in for wine tastings and such that there was “No Event Parking” there. If they could not find a place in the town center, and there weren’t many, they would need to go somewhere else. So they spilled over next door, into Seagrove’s streets, yards, and driveways. To add insult to injury, Seaside put up signs where the dirt streets of Seagrove met the brick streets of Seaside, telling Seagrove residents that the golf carts they rode about in were not welcome. With that the isolation was complete—or as complete as the sign makers could make it.

Seagrove residents responded with signs of their own. Handmade, colorful, and inviting (Seaside’s were professionally done and threatening), they read: “WELCOME to SEAGROVE, Golf Carts Allowed, Public Beach Access.” It was not so much that Seagrove wanted Seaside’s excess, but rather that Seagrove wanted folks to know which community was friendly “Old Florida” and which wasn’t. There was no mistaking the point.

Some people in Seaside were not happy with their town’s signs, and Susan Vallee, the managing editor of the Seaside Times, was one. The Times, the community’s in-house newspaper, generally avoided controversy. Most of its newsprint was devoted to praising the town and its founder, promoting and reporting events, and providing space for advertisers. In the Times, Seaside was a happy place, a Truman-esque place where nothing could go wrong. So it must have come as a surprise when above the fold of the “Holiday 2007” issue was the headline “Welcome to Seaside . . . or Not.”

Vallee could see how event parking inconvenienced Seaside homeowners and renters (how prohibiting parking in Seaside inconvenienced neighbors was not mentioned) and she could even see a reason for the signs at entries to the beach, though she found them “distracting from the beauty of the walkovers” and thought it was “a shame” that they were there. What really got to her were the signs on the beach, the signs telling neighbors that they were no longer welcome to walk along the shore into Seaside, maybe to have lunch or visit shops. It wasn’t the aesthetics of the signs, it was the message, a message she found “to be downright rude.” Besides, she added, “Seaside is, by its definition, a New Urbanist town, an open and inviting community,” and these signs ran counter to that intent.

But more than that—and here what Seaside had become, indeed what the coast had become, kicked in—it wasn’t good for business. “We depend on tourism to live and to help us maintain the property values of our homes” she wrote. “If the tourists disappear then we are in trouble.” “Calling security on people walking to the beach with their families is a dangerous precedent” because “day-trippers” not only buy from Seaside stores and shops and eat at Seaside cafes, they become renters and homeowners. Excluding people was “not what we’re about here.” She ended by urging “the Town Council and the rest of Seaside’s decision makers” to find a compromise that would “welcome guests and ensure that homeowners and renters” would have a place on the beach. “Seaside,” she reminded readers, “is just too special a place to resort to lowly ‘No Trespassing’ signs.” It was a ringing reaffirmation of the position taken by TDC officials all along the coast. Even where the beach was “private,” and Seaside could make as good a claim as any for the beach “belonging” to the community, even where there had been no nourishment by the state (and Seaside’s beach was not part of the Walton County/Destin nourishment effort), relegating visitors to that small portion of the coast that the state “owned” would not be good for the region’s image. And in the tourist business, image is everything.

Seaside’s “decision makers” got the message—or messages.

They learned that the community was not free to do whatever it wanted without regard to its neighbors or anyone else when the Walton County Fire Marshall removed the “private street” signs located at the entries to the village. It was not that Walton County particularly wanted golf carts and automobiles driving into the neighborhoods, it was that no one, not even the “decision makers” of Seaside, could put “obstructions in the streets” that would hinder emergency and fire vehicles. As for the signs limiting access to the beach, they disappeared as quickly, as quietly, and as unceremoniously as they had appeared. In Seaside the question of “who owns the beach” was settled, and the message to the outside world was clear: Seaside owns it, but you are welcome to use it. Just be nice.

Not much chance of such a compromise happening in Destin. Over there it had gone too far, and the United States Supreme Court was going to have to settle the matter.

Then while the litigants waited, on April 20, 2010, a bubble of methane gas escaped from a British Petroleum oil well off the Louisiana coast, shot up the drill column, expanded rapidly, broke through seals and barriers, and exploded. Eleven people died as the Deepwater Horizon rig burned and sank. Oil began pouring into the Gulf. Local responses were many and varied, and almost all were angry. “Boycott BP” some said. Others wanted to stop all offshore drilling. And there was the uncomfortable reminder that someday, somehow, alternative forms of energy would have to be found, and one day something other than gasoline would fuel the cars carrying vacationers to the Redneck Rivera. Environmentalists and people whose livelihood depended on shrimp and oysters argued that the marshes should be protected first, because if the oil got into the swamp and grass, efforts to get it out would destroy the very thing they were in there to save. The beach, on the other hand, could be cleaned up much more easily. This made perfectly good sense if seafood was your industry, but if your economy depended on tourism, protecting the beaches and cleaning up the water offshore was as important, if not more important, than making sure oyster beds were safe. Tourism and real estate employed more people and brought in more money than the shrimpers, oystermen, and even recreational fishing. If resources became scarce, money ran short, and a choice had to be made between beach and marshes, the debate would get mean and messy.

Deepwater Horizon/BP oil rig ablaze. Courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard.

But in the first weeks after the spill, no one had to choose. BP assured the federal government and the feds assured the coast that the company could plug the well and, according to its CEO, Tony Hayward, the impact would be “very, very modest.” So in mid-May the Hangout Music Festival in Gulf Shores went on as scheduled, with the Zac Brown Band singing “Toes”—“I got my toes in the water, my ass in the sand, not a worry in the world, a cold beer in my hand”—which was fast becoming the latest Redneck Riviera anthem. When it rained the last day the promoters threw the gates open and let everyone in free. And there was no oil on the beach. Meanwhile, people were cutting their hair and shaving their pets, stuffing the clippings into panty hose, and sending the bundles down to soak up the spill. Over in Walton County local officials approved a plan to buy bales of hay to scatter across oil-slick water to stop the plumes before they came ashore. At Calhoun’s Pub and Grub the Fishermen for Christ evangelical group met to discuss options and take things to the Lord in prayer. Everyone wanted to do something. Everyone wanted something done.

BP’s initial efforts failed to stop the leak and as more oil poured into the Gulf, concern mounted. Adding to the anxiety was the growing realization that what had caused the crisis and what it would take to set it right flew in the face of deeply held beliefs common to the coast. Over the years Baldwin County and the Florida Panhandle stood out as some of the most conservative sections of their states, if “conservative” meant believing that lower taxes would limit government and a limited government would leave citizens alone to make money and live well. Now all but the most libertarian had to face the fact that the oil rig disaster might have been prevented if the federal government had enforced drilling regulations and requirements, and if a private company, in this case BP, had not been allowed to put the public at risk for profit. Most unsettling of all was the growing conviction that it would be the taxpayer, the one who voted for limited government to save money, who would ultimately pick up the tab for the cleanup, and it would be the local economy, not BP, that would suffer. So, remaining as true to their core beliefs as the situation allowed, locals demanded that the ones responsible for what had taken place make it right, and do so with little inconvenience or cost to themselves. However, because they all knew that was not going to happen, they vented their populist anger against Big Oil for creating the catastrophe, against the federal government for not preventing it, and against the Obama administration for not making BP stop the flow of oil and clean it up.

What troubled locals most, according to a poll taken by the Destin Log, was that because of the spill the popular “perception” of the region would suffer, and the change in perception would “damage the area’s tourism market.” Which returns us, once again, to the single most important thing for which tourists came to the coast—the beach. Readers of the Log worried about how Destin would be perceived as a tourist destination, but also high on the list of things they feared the oil would do was “mar [the] crystal white beaches for years to come.”

Because “The Beach” was what they were.

Give credit to the consultants hired to come up with a name—a brand—for the product, for they came up with the right one. The region wasn’t the Panhandle, or Florida’s Great North West, or the Emerald Coast, or even the Redneck Riviera. It was The Beach. Even if tourist development councils, county commissioners, and city councils had never passed resolutions and renamed highways, it would have been The Beach. So when it was announced that the first new international airport in the United States in more than a decade, the one built on St. Joe land just north of Panama City, would be named Northwest Florida Beaches International, few were surprised.

Naturally BP tried to calm coastal fears. It also tried to limit its liability, for if it was found that the blowout was caused by company negligence, under the Clean Water Act it could be fined up to $4,300 for every barrel of oil that poured into the Gulf. Shortly after the explosion a spokesman said that only about one thousand gallons a day was going into the water. Then the company upped the estimate to five thousand gallons, and the CEO, who had said the damage would be “modest,” took the statement back and apologized. By Memorial Day, the official beginning of the summer season, scientists were saying that the spill might be ten times that much, though it was hard to tell because the pictures of oil spewing into the Gulf provided by BP were poorly focused and fuzzy. Still, from what scientists could see, enough oil was flowing into the water and drifting toward shore that if it continued the spill might become the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history. It was so bad that they were not even calling it a disaster anymore; it was a catastrophe.

Almost immediately the finger pointing began. Each of the private companies involved with the rig—Transocean, which owned it; British Petroleum, which leased it; and Halliburton, which was supposed to plug the well—blamed the other for the blowout. Democrats blamed the Bush administration for letting members of Minerals Management Service, which was supposed to be regulating offshore drilling, get literally and figuratively in bed with folks from Big Oil. The agency had “a culture of substance abuse and promiscuity” one report read. When it was revealed that offshore drilling facilities had proceeded without the proper permits and were not inspected regularly, the head of mms resigned, not that it made much difference to people whose livelihoods depended on clean water and a clean beach.

The Obama administration did not fare much better. Even the “ragin’ Cajun,” James Carville, the yellowest of Yellow Dog Democrats, gave the president a thumbs-down for his response to the crisis. Although Obama accepted responsibility for what the government did and did not do, most agreed that he should have been less trusting of assurances from oil companies that they knew what to do if there was a blowout.

Days passed, then weeks, and as BP, the EPA, the Coast Guard, and the White House bumbled along with no clear strategy, locals became increasingly frustrated. Those trying to help by sending down hair-filled panty hose to soak up the oil were told to stop because the homemade sponges weren’t effective. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection tested Walton County’s hay-spreading plan and told the county that it would not work either—the hay would not absorb the oil and would create a bigger mess to clean up. The county responded that it would rather have a bigger mess offshore than have the oil come in and spoil their “pristine beaches.” Locals applauded this defiance until the widely believed rumor got out that the hay was being supplied by a relative of a retired county official. Then some had second thoughts.

BP’s plans to stop the leak—Top Hat, Junk Shot, and Top Kill, which columnist Ron Hart said sounded “like rejected titles of Bruce Willis movies”—failed, and by early June the company was down to its last resort. Engineers planned to cut off the pipe, cap it, and draw the oil up to a waiting tanker. This had not been tried before because if it failed, even more oil would be released into the Gulf. It worked to a point. Cutting the pipe and capping it reduced the flow, but did not stop it. That would only happen if relief wells were successfully drilled, and no one would know if such drilling had succeeded until August—over two months into hurricane season.

Meanwhile, as tar balls and oil plumes drifted closer, tourists cancelled reservations and over the usually crowded Memorial Day weekend, rental property sat empty and the lines at restaurants were short. The worry spread. When Alabama governor Bob Riley told the press that if the oil came ashore the 2010 tourist season would be lost, he was talking about a disaster for more than the coast. Thirty-five percent of Alabama’s tourist income came from its beach counties and the recession-battered state would be hard pressed to replace that revenue. Florida’s Panhandle counties were threatened the same way. Tourist taxes and property assessments supported everything from schools to sewers. Property value had fallen dramatically when the housing bubble burst, and if revenue from tourism was also lost, critical services would have to be reduced. It was an environmental crisis with far-reaching economic consequences.

Whose fault was it? Increasingly the evidence pointed to BP. In the decades since the last major oil spill, oil companies such as BP made enormous profits, which they put back into drilling technology instead of developing ways to deal with a blowout. When the CEO of BP acknowledged, “We did not have the tools you want in your tool box,” he admitted the choice they had made. Still, he wasn’t telling coastal folks anything that they did not already know.

As BP struggled with the public relations nightmare created by the spill, a deep gloom settled on the region. Sick jokes like “soon they will be offering specials on preblackened shrimp at the Flora-Bama” fell flat, and when FOX News, usually considered the source of all wisdom down there, did a story that suggested that the oil had already arrived on Gulf beaches when it had not, the Destin Area Chamber of Commerce roared “what the hell” and demanded the reporter apologize. “The national media’s mass hysteria has given us a media crisis, not an oil crisis,” a chamber spokesman said.

Of course, there was an oil crisis and soon even the most positive promoters were hard pressed to deny it. Florida launched a come-on-down “The Coast is Clear” campaign, paid for by BP, for at the time the coast was, but tourists interviewed over the Memorial Day weekend told the press that they had come down because it might be the last time they could see the beach as it should be. Though BP promised to clean up any oil and “restore the shoreline to its original state,” folks there were increasingly skeptical. The Destin Log’s ongoing poll revealed a shift in opinion as residents grew less concerned that the perception of the spill would keep tourists away and more worried about the impact the spill would have on wildlife, the ecosystem, and the beaches. They knew, instinctively, that what made the coast a place where people wanted to live, where tourists wanted to visit, and where investors wanted to invest was in danger.

Following the progress, or lack of it, day after day, local folks could not help but wonder when and if anyone would take charge and get things done. “Discombobulated,” was the way the mayor of Orange Beach described the response to the crisis. People down there wanted to work, they needed to work, and there were plenty of jobs that needed to be done, but BP was not hiring, at least not hiring locals. Governor Bob Riley, visiting the coast, told the press, “Every person I saw tending boom was from the state of Maine.” Those in charge promised to do better but it seemed everyone had to check with someone else before a decision could be made. On June 4, it was reported that there were 1,150 boats available to help protect Alabama and the Panhandle, but only 112 were trained and activated. No skimmers, just promises. There were booms, but no one to put them out. And the bad news kept coming in. When tar balls were found on Pensacola Beach, the executive director of the Santa Rosa Island Authority contacted BP and asked for the cleanup crews that had been promised. Two days later, still no crews. And back at Gulf Shores signs appeared along the tide line: “HEALTH ADVISORY—PUBLIC IS ADVISED NOT TO SWIM THESE WATERS DUE TO THE PRESENCE OF OIL RELATED CHEMICALS.”

Signs warning beachgoers of oil in the sand and the water. Photograph by the author.

Headlines in the Anniston Star announced the “Wrecked Riviera.”

As frustration with BP grew, the Florida attorney general called for a greater federal role in the cleanup, only to discover that Washington’s role was limited by its own rules. Under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 cleanup was supposed to be handled through a Joint Unified Incident Command that included, of course, the oil companies. This put BP in a position to shape the response in its favor, and it did. At the same time it was becoming clear that the company had withheld information on the size of the spill in an effort, it was widely believed, to limit its own liability. Meanwhile, folks along the coast were caught in a bureaucratic tangle. They would have preferred to clean up the oil as it came ashore and submit vouchers for BP to pay. “When it comes to taking care of beaches,” Escambia County Commission chairman Grover Robinson told the press, “That’s something we know how to do.” But the law would not let them just go out, do it, and get reimbursed. They had to go through the Unified Command and BP. Frustrated, some citizens began wishing aloud that FEMA was in charge. And when coastal folk began wanting FEMA back you knew things were bad.

Local opinion of BP, tacked to the wall of a Destin Harbor bar. Photograph by the author.

Response was painfully slow. Never a favorite along the coast, President Obama alienated locals with his measured reaction to the situation and his seeming lack of righteous indignation at what happened. They called him “No Drama Obama” and wondered if anyone in Washington really appreciated their situation. Movie director Spike Lee, dismayed at the president’s cool approach to the crisis, advised Obama, “If there’s any time to go off, this is it,” but “going off” was not this president’s style. Still, some progress was detected. Finally, fifty days after the well blew, “qualified community responders” were being hired from unemployment rolls, trained, and paid eighteen to twenty dollars an hour to clean up the oil when it came ashore. However, because most of the oil was still off the Louisiana coast, that was where most of the effort was concentrated. Alabama and Florida felt slighted, and they were.

As the oil calculator on the Destin Log’s online site rolled over the 35 billion gallon mark—nearly eight hundred times what BP first “estimated” the spill to be—readers learned that “ankle-deep, mousse-like oil” had reached the Alabama-Florida line. That same day, June 10, the Mobile Press-Register reported that the boom laid out to block the oil from coming through Perdido Pass and into the inland bays, bayous, and marshes had failed, and lumps of petroleum were coming in. “There goes my flounder fishing,” observed a resident of Bear Point. He saw the oil about midmorning on June 9 and called the Unified Command in Mobile; four hours later he was still waiting for someone to come check. As he waited, BP announced yet another plan, a mechanical system of sliding screens that would close off the pass. The state would build it, BP would pay for it, and it could be ready in three weeks. But by then it might be too late. “A Chinese fire-drill” the Orange Beach mayor called it. His constituents agreed.

So they cancelled fishing events well into September, while a group organized as Seizebp.org began to demand that the government seize all BP’s assets and place them in a trust to pay for losses along the Gulf. At about the same time, Florida pulled its “Coast Is Clear” ad campaign because the coast wasn’t clear—or at least soon wouldn’t be. TDC organizations along the Redneck Riviera began an effort (paid for by BP) to promote other coastal activities—golf, relaxing by the pool, recreational shopping and eating, and bird watching (no mention of cleaning them first). An impassioned plea from Gulf Shores celebrity and restaurateur Lucy “LuLu” Buffett urged folks not to cancel reservations but come on down for what “might be one of the most memorable vacations you will have.” As she was writing, brother Jimmy was over on Pensacola beach at the opening of his new, 162-room Margaritaville Hotel, built on a site that was cleared by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. Though the timing could not have been worse, what Buffett built reflected a new approach to development that came out of the condo crash a few years earlier. Coastal developers, unable to get financing for more condos when the market was saturated with foreclosures, found investors willing to put money into motels and hotels that would not depend on individual buyers and would not encourage speculation and flipping. Margaritaville Hotel fit neatly into that trend.

“This will pass,” Buffett said as he walked along the beach with Governor Charlie Crist, and there was a belief, or hope, among them all that it would. And when it did, if it did, Buffett’s hotel would be ready. Before the oil started washing ashore, ever-optimistic real estate agents were telling inland folks about great bargains in the condo market and chambers of commerce were touting moderately priced hotels and motels. This shift in customer base suggested, according to one Gulf Shores broker, “the return of more traditional clients, rather than investors.” Adding that “Baldwin’s coastline has always been a blue-collar vacation spot,” he saw evidence that those folks were returning again. Or at least they were until the oil approached. Not even rednecks wanted an oily beach and oily water. If the coast was not clear, they would go somewhere else.

And what would become of the Redneck Riviera?