THE LARAFLYNNBOYLES

Here comes another god-damned taint-chafe of a Florida summer, and The Laraflynnboyles, the band Ronnie Altamont left behind in Orlando, are planning a tour, a fruited-plain circle through the Southeast to the Midwest and back.

Each day, Ronnie would pace the trailer’s filthy kitchen, shifting his weight from one foot to the other on the unstable linoleum flooring, vibrations shaking Squeaky the Gerbil’s cage to the edge of the sticky kitchen counter, corded powder blue phone pressed to Ronnie’s ear (Alvin paid off the phone bill with his first paycheck washing dishes for Otis’s Barbelicious BBQ’s Archer Road location), talking with the bass player—John “Magic” Jensen—about all the wonderful shows they would play, as if the band still existed, as if the tour was as inevitable as Florida summer sunshine. How beautiful the names of the cities sounded in their larynxes, on their tongues, through their teeth, through moving lips! Louisville! Cincinnati! Saint Louis! Columbia!

“Chicago!” Magic says, and, for once, the dude sounds happy, like he’s sincerely excited by something. (And no, it matters nothing to them that the show they’ve booked isn’t in Chicago, per se, but in some basement called the “Drunk Skum House” in the far western suburb of Aurora, Illinois.) Because Magic, he’s like those guys in college who are always one year away from graduating with a philosophy major he knows he’s never going to apply towards much beyond endless sardonic waxings on the human condition between bong swats while slouched in an exhausted blue couch covered in cigarette burns while watching hour after hour of the retarded sexual development of Tony and Angela on Who’s the Boss? or Cousin Balki’s unfortunate mangling of common sayings on Perfect Strangers or the incurable nerdishness of one Steve Urkel on Family Matters. It is no great stretch for Ronnie to imagine Magic down there in the slow hours of this nasty-muggy June afternoon, a cigarette burning in the right hand, a beer can in the left, waiting for the call from whichever X-ed out raver-junkie had the good drugs this week. Only, on the phone, there’s something in the way Magic exclaims (yes, exclaims!) the word “Chicago!” Like it means something. Ronnie can almost imagine the depression that Magic always tries self-medicating away melting on its own. A smile in the eyes behind the black-framed rectangular-lensed glasses, in the normally scowled mouth. Maybe he even straightens up a bit on that blue couch, turns off the sitcoms, combs out the knots in his long black hair, changes out of the t-shirt and cut-off shorts that hang off his skeletal frame, changes out of those clothes he lives in for days, actually looks forward to something beyond the next drug delivery.

“Then we’ll still move up there next year,” Ronnie assures, because it was always the plan to take the band to Chicago, to get out of Florida and move to Chicago.

(And what do you think they possibly imagine about Chicago, about the day-to-day and night-to-night realities of living there? John and Ronnie had traveled to Chicago once—to visit Chris “Chuck” Taylor, The Laraflynnboyle’s original lead singer, an avuncular improvisational actor who lived with six other roommates in a half-built loft space in the South Loop neighborhood filled with the sounds of Orange Line trains taking sullen commuters from downtown through the Southwest Side before stopping at Midway Airport, late nights punctuated by the gang war gunshots, from various exotic firearms, resonating through the streets and alleys. None of that mattered, because it was Not-Florida. It wasn’t Chicago, but merely the idea of an immense city of endless possibility.

They knew nothing of crumbling brick three-flats with water-stained ceilings, of parking tickets given out to feed a corrupt machine. About corner taverns and hipster bars where everyone knows everything about nothing much. Ronnie—In that fluorescent-lit multi-stenched kitchen, yellowed and gerbilly—wearing stained khaki pants, a short-sleeved, sweat stained holey blue t-shirt, unfashionable hiking boots, oversized glasses—has no idea. He idealizes the Midwest as some plainspoken, levelheaded tell-it-like-it-is magic land of pragmatism, and romanticizes Chicago as this city full of big booming life bursting with Roykos, Superfans, Blues Brothers, Ditkas, Albinis—when, really, all it is is Not Florida, USA—some promised land where he could be successful at what he loved.)

“We’ll play out all the time. Make some money at it, maybe even make a living at it,” Ronnie continues, peeling his hiking boots off the floor of the kitchen, looking out the dusty kitchen windows at the trailers up and down the street.

“I’ll make sure Andrew’s on board. No worries,” Magic says, talking about Andrew “Macho Man Randy” Savage, the Laraflynnboyles drummer, an affable stoner with a taste for video games and hanging around doing as little as possible.

“We’ll talk soon,” Ronnie says, and adds the word, “Stoked!” before he hangs up the phone, runs to his room, picks up his guitar, starts plucking frantically strummed barre chords—looking forward to the near-fruition of a long-held ambition, an obsession going back to adolescence, if not earlier.

•

It starts very young—at four or five even—when it’s easy to imagine yourself as the lead singer of a stadium-packing rock and roll band, between gigs as homerun record-setting golden-gloved shortstop, rushing record-breaking all-pro running back, Mars-exploring astronaut, and puppy-rescuing fireman. The rest of childhood to puberty is a potato sack race between vocations. Fireman? It doesn’t sound glamorous enough. Football? Those practices are no fun at all. Astronaut? You don’t get to Mars with a C-average in science. Baseball was the last to go. Ronnie’s eyes went myopic around the time his family moved to Florida, and the new place was too hot to bother with the Pony Leagues, and besides, by that point, music offered some kind of map through adolescence’s chaotically inextricable terrain.

Through a combination of practical elimination of childhood dreams, and emerging passion, Ronnie Altamont finds rock and roll. At first, his only source was MTV—the J. Geils Band, Quiet Riot, Van Halen. From there, he tunes into the “Album-Oriented Rock” stations that would later be relabeled “classic rock,” where bands like Led Zeppelin, Boston, and Pink Floyd—then, as now—played in an eternal loop. Compared to the music of the mid-1980s, classic rock was, indeed, classic. The popular music of 1986-1990, Ronnie’s high school years, slogged through an endless succession of soulless, talentless swill. Ronnie ignores all of this and obsesses on the storm und drang of The Who.

Here’s when the dream (Since this aspires to be The Great Floridian Novel, perhaps it should be called The Dream) really possessed Ronnie, because The Who—and Pete Townshend in particular—were accessible in ways the other so-called “classic rock” bands could never be. While bands like Led Zeppelin and the Stones in particular were often essentially saying “I have a big dick and enjoy sex with lots of women”—Townshend said: “I have no idea what I’m doing or even how to express it.” Here, for Ronnie, was the teenage wasteland of the mind, heart, and glands.

High school. What was that bullshit but one big daydream of drawing band logos all over folders? Putting the head down on the desk and drooling in sleep as the teachers went on and on about topics that weren’t rock and roll and were therefore unimportant? Songs—lyrics, guitar solos, bass lines, drum fills—ricocheted around Ronnie’s skull like dozens of pinballs. Waiting for the final period of the school day—marching band—to go bash a snare drum for an hour. Then, it was home, and straight to the bedroom to brood on some inaccessible girl-crush, as The Who played from the nearby stereo, every night and all weekend. That plea: “Can you see the real me? Can ya? Can ya?” Quadrophenia as the soundtrack to hours staring at the popcorn ceiling required in all those hastily-built Florida suburban homes, thrown up in an attempt to keep pace with the Great Yankee Migration of the 1980s. Textbooks, as uncracked as they were when he got them in August, rarely left the morass of his locker, where pictures of Townshend and Moonie in leaping drumsmashing windmilling glory adorned the locker door’s interior side. High school. It wasn’t glory. It wasn’t disgrace. It was nothing but a daydream. A Bartlebyesque refusal.

All that changed with the drums. Ronnie constantly practiced, and studied Keith Moon in particular. He absorbed everything about The Who—every Townshend leap, Entwistle flurry, Daltrey pose, and especially Moonie’s ability to make the whole kit shout in tumultuous waves. He read every book he could find on The Who, reread those books, owned every Who album (even the bad ones), and, somehow, this led to discovering punk rock (because Townshend liked the Sex Pistols and the punks from that time generally liked The Who). It wasn’t through the punk rockers in his high school (although he would eventually be friends with most of them—William, Neal, and Paul, among others), who seemed at the time like another bland choice in the salad bar of high school cliquedom. It was like this solitary quest to find the songs and the bands that got it—“it” being whatever it was you go through as a teenager—right. By the time 1990 came around, the discovery of bands—old and new—local, American, English, whatever and wherever—was Ronnie’s drug, the thing that got him high and excited to live. At some point during this time, Ronnie switched to guitar, finding it cheaper and easier to carry around than a drumset.

Bands started and ended quickly in that time, with names like The Adjective Nouns, Murderous Kumquats, and Poop, none of them very good. Two weeks before graduating high school, Ronnie meets John “Magic” Jensen through the singer of one of these interchangeable bands. With Magic, Ronnie finds, for the first time, someone who shares his musical obsessions, who has spent similar hours flipping cassette tapes in his bedroom, supine on the bed, staring at the ceiling. For Magic, these obsessions are eclipsed only by his love for marijuana. Ronnie and Magic are inseparable. Magic taught himself to play bass, loves the music of Frank Zappa and Jane’s Addiction the way Ronnie loves the music of The Who and (by that point) The Buzzcocks. Magic turns Ronnie onto the Dead Kennedys, Ronnie turns Magic onto the first two Ramones albums, they both watch the bands in The Decline of Western Civilization, and knew that somewhere—not where they were—but somewhere—was a better world of live music and danger and adventure. Magic rarely left his room. The room had his bong, his bass, his music, his pornos, the TV. He would sit in a red recliner, stoned, watching Star Trek: The Next Generation on mute, studying Natasha Yaar’s tits with the Butthole Surfers providing the soundtrack. There was nowhere else to go and nothing else to do, and the life they saw glimpses of through the music and the TV wasn’t where they were, so they were bored all the time (not knowing that there were far worse things in the world than boredom) and they had no idea how to alleviate it—naïve and generally understimulated—sitting in the darkness of Magic’s bedroom where the aluminum foil covered the windows and blocked the sun of those insufferably hot days. Magic sits in his room where the TV is never off, and mutters perceived truisms like “Life doesn’t suck, it’s just boring,” and “They’re fuckers man, fuck ’em.”

Nothing comes of the bands they start because, well, drummers are drummers. And not only that, good drummers were impossible to find. There were plenty of people with drumsticks—and some of them even had drumsets—and some of them could even keep beats—but none remotely shared Ronnie and Magic’s interests.

Finally, after they’d both started attending the University of Central Florida, they find a drummer in Willie-Joe Scotchgard, who actually plays the viola, but knows how to keep a beat. School lets out, and early summer is always a terrific time to start a band, so Willie-Joe drives home to Lakeland and brings his drums back to the living room of the second floor of some remarkably tolerant apartment complex in UCF’s student ghetto, and it is here, the four of them (“Chuck” Taylor still living in Orlando, an alum from Ronnie and Magic’s high school, old friend and dopesmoking buddy from the drama club Magic dabbled in, Magic’s interest explicable in that the girls were much cooler and better looking than they were in the marching band) buy six-packs of Falstaff Beer (on sale for two dollars at the nearest Publix), and goof off the evenings and nights beered up enough to play the dumb songs Ronnie and Magic had written.

The songs are satirical, silly. Maybe they’re a punk band. Maybe they aren’t. (“Jesus, who cares?!?” Magic yelled after Ronnie voiced his concerns, and that settled it.) Ronnie names the band The Laraflynnboyles, after the actress on Twin Peaks, because Ronnie sees in her what he never could quite see in all those peroxide plasticine Florida women—someone beautiful with an inner vulnerability, and yeah—goddamn right—it’s all projection, but you gotta understand: Ronnie had to find everything alone, the way all kids in exurbs with the guts to think for his/herself must do when slogging through the Great Adolescent American Mindnumb.

The songs: Country-Western odes to their Altamonte Springs hometown (remarkably similar to The Kinks’ “Willesden Green”), songs with one-line lyrics repeated over and over (“Sweaty Hands”—whose only lyric was “Sweaty Hands: Whenever I see you I get sweaty hands,” a tribute of sorts to Flipper’s “Sex Bomb”), the requisite 90s is-this-ironic-or-is-it-not-quite-ironic-but-something-in-between-irony-and-earnestness covers of Kiss (“She”) and .38 Special (“Hold On Loosely,” Chuck Taylor’s star turn, the way he’d point like Elvis and shake his comically avuncular frame at the smattering of ladies in attendance at each show as he sang, “You see it all around you/good lovin’ gone bad.”), songs about this big white 1970 Chevy Impala driven by a girl Ronnie briefly dated, who would pick him up and take him to all the weird little clubs and bars and (true) chili bordellos dotted across Orlando’s landscape as they made the cute little inside jokes boyfriends and girlfriends make while listening to a cassette of Lou Reed on one side and Screaming Trees on the other endlessly flipping back and forth between the two, she politely indulging the “I will always be punk” rants he would veer into from time to time, as was the style of the early-to-mid 1990s), a song Magic wrote called “Chilean Sea Bass” (that being a metaphor invented by Paul to describe cute girls), the entire presentation—when they had shows—layered in a thick Kiss rock and roll swagger, like if Kiss had one too many beers before playing. It was funny to them to act like Kiss—it was funny for Ronnie to howl Paul Stanleyisms like “I know everybody’s hot! Everybody’s got the: ROCK AND ROLL PNEUMON-EE-YAAHHHH!!!” as Magic shook his fist and growled “Ohhhhhhh yeahhh-ahhhhhh!” like Gene Simmons. They were laughing at their childhoods of bad MTV, bad bands, bad music, at being sold a bill of jiveass rock and roll goods.

Unconsciously, they were trying to link (and reconcile) Kiss with The Minutemen, a Promethean-enough endeavor had they actually known how to play, but by falling way short of either mark, they had their own thing going, no matter how sloppy and ill-conceived. It was funny. It was cathartic. And the music, for its time, wasn’t half bad.

They played gigs all over Orlando—living rooms, backyards, coffee house open-mics, any bar or club that would have them. In Gainesville, they played a kitchen where the show ended with Ronnie tackled by all his new/old friends—the kids he never got to know in high school like William, Neal, Paul—as they stole the mic and screamed along to “Sweaty Hands.” Friends, old and new, got into the spirit of the jokes, the spectacle, the seriousness of the joke. As for the rest, as Magic was still fond of saying, “They’re fuckers man, fuck ’em.”

The music and the writing liberated Ronnie. Everything was really coming together—ladies, parties, tons of friends, fan mail about the column he wrote. Quite often, the days and nights spent in that blissfully naïve corner of the world called the University of Central Florida were blissful, languidly blissful. It was around this time when Ronnie met Maggie—who was three years younger, three times more attractive, and three times sweeter than Ronnie—and it was the closest thing you can get to “love” in the emotional immaturity of the late-teens and early twenties. In the middle of winter, Ronnie and Magic visited Chuck Taylor (who moved to Chicago after a year in the band to pursue dreams of improv comedy), and the city felt right, comfortable, even if it was 80-degrees colder than what they were used to. The action and the energy appealed to Ronnie as much as the music scene and his passing familiarity with Touch and Go, Drag City, Thrill Jockey . . . but really, so much of his love for Chicago and his desire to move there was projection, pure and simple, where Ronnie took everything Central Florida did not have—everything Ronnie wanted in a place to live—and tacked it onto Chicago. Besides, in terms of big cities, Chicago at the time felt like the only viable option. Atlanta was too southern for Ronnie. New York never came up. It was in transition from the Snake Plissken nightmare of the past to the Walt Disney nightmare of the future, and no one was moving to Brooklyn in those days. The West Coast was too far away . . . it didn’t seem real. There was something about the Midwest that appealed to Ronnie. Pragmatic. Level-headed. Honest. Direct. Tellin’ it like it is! Surrounded by people who think they’ve cornered the market on sanity and reality. He had heard of Lounge Ax in passing, hadn’t heard of Empty Bottle or even Wicker Park . . . it wasn’t so much about the music scene of that time as it was the idea of a city with so much possibility. Where Orlando felt hopeless, and Florida felt stultifying, Chicago felt and seemed inexhaustible, and Chuck Taylor, through his actions, his talk, his changed demeanor (urban, fast, smart) seemed to confirm all these projections. Drunk on tequila from the bar Chuck worked at, Magic and Ronnie agreed, while sobering instantly from the below-zero windchill on the cab ride back to Chuck Taylor’s half-built loft space, that they would move there when they graduated.

In Orlando, they recorded on 4-tracks in Magic’s apartment, and continued playing shows, and everything leveled off and that was fine even if the band wasn’t really going anywhere. But where was it supposed to go?

Realistically, there were only so many places to play, and only so much you could do in Orlando. Graduation loomed. Willie-Joe Scotchgard graduated first. He moved to Cleveland to study the viola in a conservatory. They found another drummer—high school friend Andrew “Randy Macho Man” Savage—and soldiered on, but there was a decline in effect here, magnified by Orlando’s omnipresent drug culture. Roofies were big that year—1995—and they weren’t used by The Laraflynnboyle’s circle of UCF friends for date rape, no matter what the papers say is its use in the uberculture. They made mean, surly, loudmouthed drunkards out of everyone, no matter how kind and considerate you normally were. Magic found roofies a fine way to numb the empty afternoon and evening hours. They magnified his already profound bitterness. For his part, Ronnie drank more and more, unsure of what to do with himself, especially after graduation, and his newspaper column—this column he had come to rely on so much as his identity—was no more once he graduated and received the diploma he didn’t know how to use. Ronnie washed dishes so he would have time to write The Big Blast for Youth, and continued practicing with The Laraflynnboyles even if too many gigs ended badly from Ronnie’s overindulgence of malt liquor, and Magic’s nasty borderline violent (lots of fights broken up at this stage) roofie glaze. In this cloud of post-college uncertainty, as his behavior grew more and more erratic, as the smile on his face disappeared, as he floundered from job to job, Maggie left.

At some break in the clouds, Ronnie took a good look around. The only girls left were bisexual raver junkies. All the dudes he knew were content to be high all the time. He felt Orlando closing in on him. He was back to sitting around in his room, in the house he lived in with Chris Embowelment, playing Who records all night, trying desperately to avoid the thought that it was time to grow up and get a regular job and spend the rest of his days in comfortable, expected middle class, forever nagged by some variation of the question “What if?”

The only thing Ronnie could think to do was to flee for Gainesville. Ronnie and Magic weren’t exactly best buds by this point—having little to connect over anymore besides what remained of the band—but Ronnie assured Magic the band would continue, somehow. They had always wanted to tour, and now Ronnie would get them more shows in Gainesville because it wasn’t really that far away from Orlando (just far enough), and the music scene seemed better, what with all the punk rock you could shove down your spiky-haired throat and all. A stopgap, anyway, until they could get it together to move to Chicago. But Ronnie needed the change, needed the stimulation of others who weren’t all about shitty drugs anymore, to a place that had more going on. Gainesville was all Ronnie could afford.

All of this swum around in Ronnie’s quixotic brain as he played his unplugged electric guitar in his room after getting off the phone with John “Magic” Jensen. The tour would make things right again. Getting shows in Gainesville would make things right again. And then, soon enough, packing up and leaving for Chicago would make things right again.

It would be a beautiful and triumphant summer, and Ronnie couldn’t wait to jump into it.

RONNIE AND SALLY-ANNE ALTAMONT

Ronnie calls his parents to share the good news.

“A tour,” Sally-Anne Altamont repeats, when presented with said good news.

“Yeah! Definitely!”

“You have no money, Ron. You have no job. You’re not even in the same town anymore as those other guys, who never exactly struck me as hardworking and dedicated musicians. None of this strikes you as, I don’t know, problematic?”

“It’ll be awesome.”

“Awesome.” After a three mile run on the beach, always, a focus, clear candor, often lost in the lazy days of retirement, misplaced in the vagaries of meditation. “It’s like you’ve lost your mind ever since we moved to South Carolina and you went off to college.”

“That was six years ago.”

“Exactly.”

SIOUXSANNA SIOUXSANNE GOES BOWLING

It’s “Rock and Bowl Ain’t Noise Pollution Nite” at the Gainesville Bowl-O-Rama. Siouxsanna Siouxsanne (an unfortunate nickname, lingering from high school during the peak of a Siouxsie and the Banshees obsession) is here tonight, throwing her sixth consecutive empty frame over on Lane 15. She is a terrible bowler. Most gothic bisexuals are.

The Run DMC version of “Walk This Way” pounds over bowling shoes squeaking across the wood. Swirling jade, black, and vermillion AMF boulders spin down the lanes, thundering like tympanis before grand old school showbiz introductions, until the percussive woodblockish rattle of the overturned pins break the tension, as the ball lands with a mechanical plop into the great unknown/unseen of its mysterious journey beneath the lane to be gracefully unfurled from the gaping maw of the retriever. From the game room, spasmodic videogame queefs. Across the lanes, strobe lights flicker. Black lights glow tubesocks and lint. The disc jockey is Sweet Billy Du Pree, legendary 1970s FM DJ back when Gainesville had a hard rock station called BJ 103: The Tongue.

“This one’s goin’ out to all the real rock and bowlers who still remember quality rock and roll,” the venerable Du Pree rasps through the crackling speakers of the public address system, voice worn low and raspy through a life of whiskey and Quaaludes. The elegiac opening strains to “Magic Power” by the Canadian power trio Triumph fade in and set sail across the lanes on a sonic odyssey of magic. And power.

“Shit! Shit! Shit! Turn right, you stupid goddamn dick ball!” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne yells over the din after yet another ball veers left well before having a chance to knock over any pins. She turns, straightens her posture, recomposes, and all inebriated clumsiness and aggression in the toss evaporates. She is tall, in a long black dress and black stockings, a slinky slide in the walk in faded red white and black bowling shoes unaccustomed to supporting this much grace. There’s a relatively austere use of makeup (We can’t look like we did in high school now, can we?) across the cheeks, eyelids, and lips of her art school features, a dyed-black salon cut somewhere between a page boy and a bob. Pale. So pale. It takes effort to get skin like this in Florida.

Siouxsanna Siouxsanne loses her footing, unused to the lack of traction as her right heel skids sideways. She flails to the floor in what seems a comedic pratfall, hurriedly rises, mutters, “I’m too llllllllloaded to be here!” over the not-quite-mocking laughter of friends.

Ronnie Altamont is impressed.

He silently observes the bowling and the good time laughter of this distinctly middle class college crowd in their ironed thrift store tees and unholey back-to-school mall pants. Ronnie leans forward against the bowling ball racks, standing on the unfashionably brown plaid printed carpeting on the three steps above where the bowlers sit changing shoes, keeping score, chugging brews. Here are the easy smiles and burdenless leisure of summer vacation, a jarring change from the dismal poverty Ronnie had grown accustomed to, those long muggy hours in his bedroom in the trailer alone, listening to The Stooges and trying to write. School is over, but only temporarily for them, but for Ronnie, he’s reminded of how he felt like an interloper that first day he and Kelly set foot on the UF campus to score free Krishna food.

After a sweat jam at Paul’s, Ronnie drove William and Neal to the Gainesville Bowl-o-Rama—where some nnnnnnnnugget William was trying to hook up with would be with a few of her friends. They would all be Ronnie’s friends soon enough—all twelve of these amateur summer vacationing bowlers—but only Siouxsanna Siouxsanne stands out to Ronnie, in her mix of post-goth grace and sloppy belligerence. Ronnie, not the grown-ass man he thinks he is, still young enough to treat every crush like he is the first person to ever have these feelings. So charming! Siouxsanna Siouxsanne, stomping up to the line to try yet again to knock over a pin—any pin—falling over the line as she flings the ball “granny style,” long lithe arms pulling and spinning the rest of her forward until she loses her footing, spins, plops backwards while the ball—chipped and yellowed with white streaks like a dusk thunderstorm—bounces over the first lane to her left and continues rolling two lanes over, sabotaging the very serious play of a muffler shop’s weeknight bowling team—where it knocks over four pins. Her friends cheer at this, they clap and congratulate her for finally getting on the scoreboard. The muffler shop’s weeknight bowling team6 has to smile, no matter how jaded they’ve become to the general misbehavior of college students. It helps that the interference in their very serious league play is from a girl who would be real pretty if she didn’t wear so much makeup, if she didn’t dress like she was leaving a funeral, if she laid out in the sun once in awhile and got herself a tan. Not that they would kick her out of bed or nuthin’. They’re just sayin’.

“FUUUUUUCK YEWWWWWWWW!” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne brays to the paneled ceiling’s spinning multi-colored disco lights. She’s on her back, brain floating in and out of booze-fueled, med-soaked half-dreams of car trips with her parents—the only child in the backseat staring out the window from Orlando to St. Pete or Fort Myers or wherever they would go to see family—watching the lakes and swamps and bays and gulfs and oceans—pretending she was some kind of superfast manatee diving in and out of the sharp glittering waters (no matter the color—the pea soup of

the swamps or the worn concrete of the ocean or the choppy blue of the bay) keeping pace with the off-white wood-paneled Country Squire station wagon and flying out of sight above them when the waters ended until another water body appeared to the left or right as Billy Squier sings “my kinda lov-uh/my kinda luv-uh/my kinda luuv-uh . . . ” Two hands wrap around damp armpits and pull Siouxsanna Siouxsanne upright. She tries walking, but her legs are not taking any orders from her brain. Two friends—William and Neal, actually—lift her along on either side like she’s a running back carried off the field after a knee injury to the gracious applause of the audience, only there is no applause, just snack bar stares and beer bar glares. Even the lanes are silent, as these twelve (plus Ronnie—transfixed and fascinated and in love) move en masse toward the exit.

Sweet Billy Du Pree turns down the Billy Squier, announces, “Ladies and gentlemen, you know I used to party hard, but I also used to party safe. Let’s keep it street legal out there at the rock and bowl, yadig? Here’s another song that could never get old: ‘Whole. Lotta. Luuuuuuuuv.’ ”

Siouxsanna Siouxsanne lollygags her head rightward, yells “You suck ass!” to the DJ booth. Friends shrug at Sweet Billy Du Pree, mouth the word, “Sorry.” Ronnie looks to Sweet Billy Du Pree, up in the DJ booth. He wears a red bandana on his upper forehead. A faded black “The Ultimate Ozzy” tourshirt, swollen from the beerbelly. Aviator sunglasses. He nods his head in rhythm to the “du-nuh, du-nuh, nuh” of the “Whole Lotta Love” guitar intro. The rocking and bowling resumes.

Ronnie trails behind this group as Neal and William keep Siouxsanna Siouxsanne from falling to the ground, passed out and dreaming of childhood manatees. In and out of consciousness, she yells expletives, mumbles unintelligible moans between drools. So beautiful, Ronnie thinks. In the parking lot, two more friends join in and hoist her into the back of a Volvo station wagon—one of those relaxed boyfriend and girlfriend couples you know will be married shortly after getting their degrees—and off they go, Ronnie watching the Volvo’s boxy red taillights fade away across the mammoth parking lot. In the midst of the parking lot talk—the shrugs and the “That’s Sioxusanna Siouxsanne for ya’s,” the ride back to William and Neal’s where they will have one more beer while listening to CCR (and still talking about Doug Clifford like it will really happen), Ronnie wants to ask about Siouxsanna Siouxsanne, but he knows no one will tell him what he wants to hear, knows no one will say, “You and her, you’d be great together, Ronnie!,” knows no one will claim that she isn’t as crazy as she was acting at the Gainesville Bowl-O-Rama for “Rock and Bowl Ain’t Noise Pollution Nite.” So he holds it in, “it” being whatever passes for “love” in his heart, mind, and other, less noble, body parts.

QUASIMODO IN THE DISHTANK

Alvin knocks on Ronnie’s bedroom door—three soft, unassertive taps.

“Yeah what?” Ronnie grunts, annoyed, because he’s thinking about maybe doing some writing as he rifles through his compact discs for something to listen to. He’s busy, you understand.

“I got my first paycheck from Otis’s Barbelicious BBQ, and I was wondering if you wanted to go out for Chinese food. My treat, pfffff.”

All thoughts of busyness, of thinking about writing while listening to music, vanished from Ronnie’s mind, replaced by a massive steaming mountain of pork fried rice. Ronnie hops off the mattresses, leaps to the door, opens it. “Let’s go.”

The restaurant—The Ancient Chinese Secret—is a two-minute drive down 34th Street. Alvin drives, narrowly avoids sideswiping two cars, honking blurs in the myopic haze beyond the range of his thick glasses. “Pfff. Guess they didn’t see me,” Alvin says. Ronnie laughs at this, trying not to look at the murderous glares from the narrowly avoided cars, thinking how absurd it would be to die in a car crash simply because he wanted to score a free meal.

They sit in a cool dark dining room in a booth by the window overlooking the broiling blinding plaza parking lot. Alvin talks about his job. And talks. And talks.

“So I wash the dishes, the forks, the knives, the spoons, the spatulas, the bowls, the plates, the storage bins, and whatever they want me to wash, really—pffff!—but that ain’t all I do there. I stir the beans, butter the bread, take the clean plates to the bus boys, take out the dirty linen at the end of the night. It ain’t bad really, pfff.” Yes, Ronnie is aware of the job description here, and not only because he has prior experience in the dishwashing field. Alvin has told him all about the routines of his work several times already. Butter the bread. Stir the beans. Take out the dirty linen. Wash what they take back to me. Pfff. Ronnie is too hungry to listen, to care, to bother with trying to respond to anything Alvin says, because Alvin doesn’t respond to what you say, he simply continues talking about whatever the hell he wants to talk about. As Ronnie waits for his food, Pluto orbits around the sun in one complete rotation, empires rise and fall, Ice Ages come and go and come and go again. Still, no food. Alvin keeps yammering. Pfff. But it’s a free meal, and if Ronnie can eat something, he can go to Gatorroni’s, where he’ll score free beer from William and drink all night. If only this food would get here already.

“. . . So yeah, they call me ‘Quasimodo’ at work, pfff.” Alvin mentions in the middle of this nonstop yak.

Ronnie snaps back in the booth, jarred from his impatient reverie. Ronnie huffs. Ronnie is offended. “They call you ‘Quasimodo?’ ” Ronnie huffs once more. Ronnie is offended. “I can’t believe that, Alvin. That’s so mean.”

“Well, it’s nothing I ain’t used to, pffff.” Today, the “pfff” sounds especially resigned, like a deflated tuba.

“No, man . . . that’s not right,” and Ronnie, he actually tries imagining that there is someone inside Alvin that’s real, someone suffering an endless series of slights, guilty of nothing but being born with Swedish wino pubic hair scalp, acne, buckteeth, that smell. Everything is off about him, and he knows it and has to live with it. Ronnie could look around town, could look at himself and those around him, and at the end of the day, no one was stranger, no one was a bigger nonconformist than Alvin. He didn’t even try. He was born into it. Everyone else magnifies their nonconformity just enough to get laid but not enough to adversely impact the quality of life they are accustomed to. Beyond a heightened sensitivity and artistic inclinations, they didn’t suffer daily the way Alvin suffered daily.

Ronnie manages an “I’m sorry, man.”

“Pfff.”

Finally, the food arrives. Sweet and sour chicken for Alvin, pork fried rice for Ronnie. After subsisting on little besides Little Lady snack cakes and microwave burritos, Ronnie relishes it all—the taste and the chew, the swallow and the downward movement, the warmth and the fullness. All thanks to Alvin. Shit, Alvin’s the entire reason Ronnie’s even here in Gainesville. Who else would let him live this way? Rent-free. Bill-free. And all Ronnie does is make fun of him.

“Well, that was great,” Ronnie says on the drive back to the trailer. “Best meal I’ve had in a long time.”

“I’m thinkin’ about watchin’ a movie tonight, pff,” Alvin says on the drive home. “Ya wanna watch it with me?”

Ronnie thinks it over as Alvin turns right off 34th Street onto the side street leading to the trailer park. After free Gatorroni’s beer, when William gets off work, they’ll show up at peoples’ houses, see what they are doing, or maybe they will end up at the Rotator. Nothing definite. With some food in his belly, it would make drinking that much easier.

“Naw, man,” Ronnie says. “I made plans.” Alvin parks the van. Ronnie immediately opens the door, hops out. Oh yeah. He almost forgets to say, “But thanks for dinner.” Alvin watches Ronnie get into his car and drive away.

“IT’S THE BEGINNING OF THE BEGINNING OF

THE END OF THE BEGINNING,” SEZ ROBBIE

ROBERTSON IN “THE LAST WALTZ” . . .

. . . is the quote I’ve been running around in my head lately after watching that movie at some hippie party at UCF (all the little subcultures hang out together on the fringes, so you end up being around hippies, no matter how, like, fuckin’, punk rock or whatever you are). At first, I scoffed at it, and I don’t remember much of the rest of The Band playing with all their old fart friends—once the roofies kick in alls I remember is a vague steady blunt surly torrent leaving my mouth and the delusion that my brain is finally making some truly wonderful and fearless connections re: my life and shit.

But yeah: What does that mean? I mean, I know it’s probably just some cocaine koan bullshit when Robertson says that, but, ok, let’s break it down:

We know it’s the beginning, but it’s the end of that beginning, but it’s the beginning of the beginning of that end of the beginning.

I‘m starting to think I know what he means by that, as me and Macho Man Randy pull up to what Ronnie tells me is called the “Righteous Freedom House,” one of these large old houses people here live in where bands play every weekend, one of those Gainesville punk rock houses Ronnie busts a nut over in his corny punk rock fantasies.

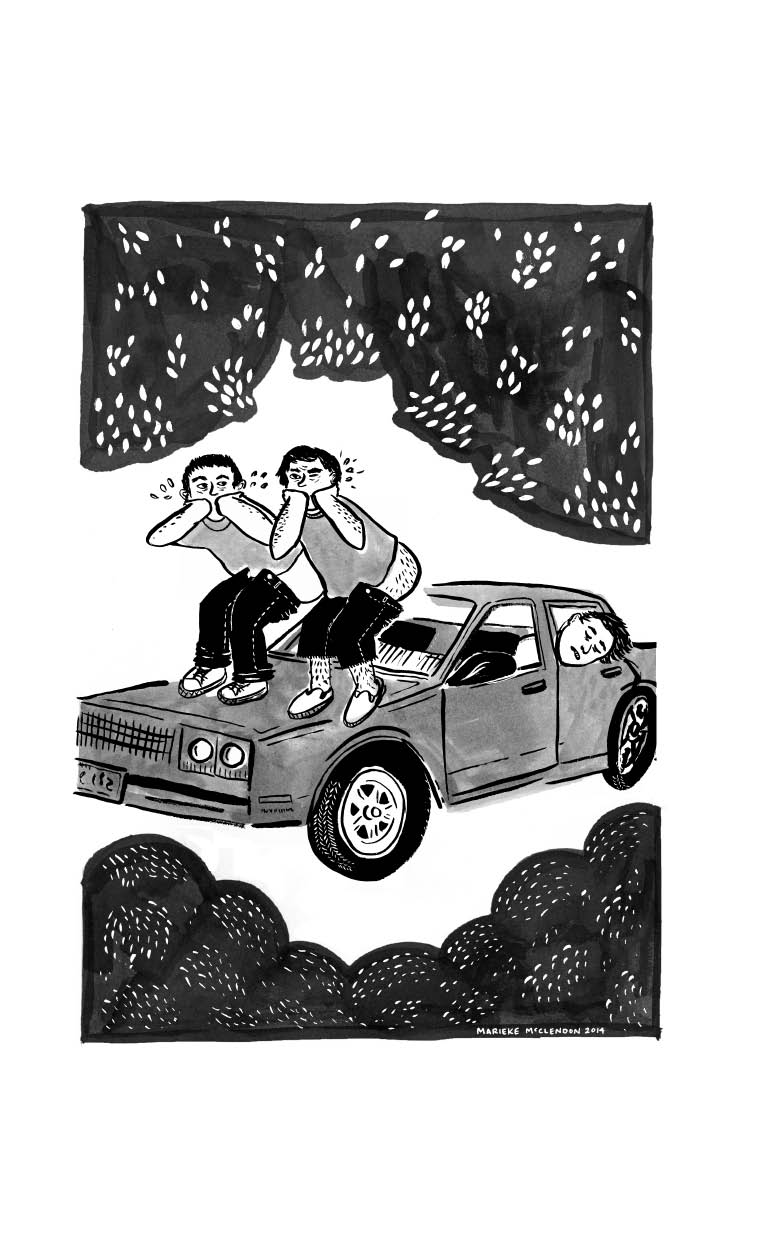

“This better be good,” I say before stepping out of Randy’s brown-exteriored, gold-interiored 1981 Chrysler Cordoba—you know, the car with the “fine Corinthian leather” ol’ what’s-his-name from Fantasy Island promises, only Randy’s car isn’t fine Corinthian anything—cloth seats blackened with dirt and tears from lugging amps and drum gear from one end of Orlando to the next, the paint job worn away by the sun—hood, roof and trunk dented by hailstorms—and somebody (Ronnie, probably) started calling it “The Poop Ship Destroyer” after that Ween song. Randy climbs out, looks across at me, over the pock-marked roof as I continue, “I have five roofies in my pocket, and I’m not afraid to take them if this isn’t.”

Of course, Ronnie couldn’t grace us with his presence to load in the gear, and actually—nobody’s here right now as we’re in that awkward time of after dinner and before the party when you wonder if anyone’s going to bother showing up, so Randy and I trudge back and forth from The Poop Ship Destroyer to the corner of the living room that’s been allocated as the place to plug in and set up by the scenester (the thing about Gainesville that I never understood was how everybody here kinda looks the same . . . it’s like that line in Quadrophenia: “it’s easy to see / that you are one of us / ain’t it funny how we all seem to look the same?” (And now you see why I’m not the singer for The Laraflynnboyles. If you think Ronnie’s singing is bad, and it is . . . )) with his black band t-shirt and hair dyed some bright unnatural color and very short on a frail vegan frame and they’re all nice enough, I guess—these wannabe prodigies of Ian MacKaye, and you can tell in their behavior, they’re always sitting there thinking “What would Fugazi do here?” but we trudge across the small treeless grassless dirt front yard into the large living room covered in (of course) show fliers and (of course) the iconic photographs of like Minor Threat sitting on the front steps of the Dischord House, Jawbreaker sitting on an old couch, some angry singer I don’t know doing that “breaking the fourth wall” thing all these angry desperate singers do when they run up to a crowd of equally angry desperate kids in the audience who gather around the mic to scream along to the words they’ve memorized like solemn Boy Scout oaths of forthrightness to the Den Leader, interspersed with pictures of Kiss and Iron Maiden and Van Halen that somebody here finds funny, and, come to think of it, I find it funny too, meanwhile Scenester dude stands over us as we plug in and set up asking questions like “So how’s the Orlando Scene these days?” and I pshaw and grunt a “Sucks” and Randy shrugs and says, “Yeah,” and Scenester dude presses on and asks us about different bands in Orlando and yeah, we’ve heard of these bands, they all have names like December’s Februrary and Car Bomb on a Sunday Afternoon, and I can’t stand those bands, but I try to be polite so I says, “Yeah, we’re not really into any of that,” and Scenester dude gets the picture.

True to form, Ronnie shows up the moment everything is finally set up. He’s with William, Neal, and Paul, and it’s like some kind of high school reunion with our hearty ha ha has and backslapping embraces. Ronnie seems happier. He looks like hell—disheveled hair, smelly unwashed clothing, an underfed weight loss—but he does seem happier the way he stands around us smiling, looking from me and Randy to the other guys. He always wanted to be a part of something. I think that’s why he wrote that retarded opinion column for the school paper. I really do.

Anyway, Paul, who communicates entirely in inside jokes, volleys about five inside jokes my way in about twenty seconds, and it’s like we’re all seventeen or eighteen years old again having a late night at the Denny’s on State Road 434 back in Orlando, only, instead of ten of us taking up the largest booth in the restaurant, ordering nothing but a basket of fries and ten glasses of water, it’s six years later, and we’re living whatever short-sighted dreams we had back then of playing in bands. It’s really all we ever talked about, aside from girls.

Neal steps up to Randy, rubs his recently emerged beer belly. “Looks like Tara’s keeping you well-fed, heh,” and as he rubs, he pokes Randy’s belly and punctuates it by saying, “Heh! . . . Heh!” until Macho Man Randy shoves him away, laughing (the dude doesn’t have a mean bone in his body) and says, “Fed and fucked, dude. You know how it is . . . ”

“I only know about the second one,” Neal says, and we laugh. It really is great being around these dudes again. It almost makes me want to like Gainesville. Almost.

Anyway, they show up with a case of Old Hamtramck, and they’re already drunk, so it looks like me and Randy have some catching up to do before we start playing. People slowly start showing up, peeking into the empty living room, taking one look at us, realizing they don’t know us, then stepping out to shoot the shit in the front yard. I shotgun three beers in a row, and my friends—oh, my friends!—they circle me and cheer me on in a way that’s sincere in its ironical references to collegiate dude squad bro-ham peer pressure. It’s like we’re making fun of it even though it’s exactly what we’re doing.

“Watch this, fuckers . . . ” I say, feeling what I wanted to be feeling right about now (and those roofies are weighing down my right jeans pocket), and my key pokes a hole in the middle of the Old Hammy can and the beer floods my throat and my brain turns energetic and sluggish all at once as the heaviness of the suds fills my chest and when the can is empty, I crush it against my skull a la Ogre in Revenge of the Nerds, and my five friends cheer me and suddenly we’re all chanting “Nerds! Nerds! Nerds! Nerds!” for no reason, except, if there’s one thing we have in common, it’s that we like to start ironical chants with each other after we’ve been drinking. When the drink takes hold, we love to yell. And now, I’m ready to play, because, honestly, I don’t give a fuck if we sound good or not. Fuck these people. Fuck Gainesville. These smirking phony tattooed up scenester types with their identical hair and identical dress, standing in their little clusters of small town self-important drama. What Ronnie sees in any of this, I will never know. Behind the amp, I pull out the roofies and pop three into my mouth, chase it with the beer. Great. Let’s rock.

The show goes about how I figure it will. I’m drunk, feeling the pills slowly kicking in, forgetting whole songs as the set progresses, weaving in and out of consciousness, weight shifting from one foot to the other. Ronnie ain’t much better, and actually, he might be worse, because he was at some bar for three hours before showing up to play. Macho Man Randy wasn’t the best drummer to begin with, and now, he looks green with beer sickness, like he might throw up on the drums so when he hits them the puke hops and leaps the way glitter does in those glam metal videos of our youths. Only Paul, Neal, and William bother watching us, and all they do is yell the words “Rock! Beats!” (whatever that means) over and over again while throwing their empties at our heads. The scenesters peek in through the front screen door long enough to smirk at our band—this band we’ve been doing for so fucking long now called The Laraflynnboyles—and who even knows what that’s referencing anymore?—who even remembers Twin Peaks?—and no wonder they’re completely indifferent to our stale band with our stale jokes (our Kiss between-song banter of “How’s everybody doin’ tonight! Yeah? Who wants vodka and orange juice?” or whatever the hell we’re saying tonight) pointing out via wornout satire the, this just in, stupidity of the music we call Rock and Roll. And yet, at the same time, it’s like, we’re just having fun here, and isn’t this what it’s ultimately about? See, that’s what pisses me off the most about Gainesville. These doctrinaire fuckin’ . . . Gainesville scenester types. So humorless. So unable to relax and have, you know, f-u-n. Yeah, we suck. So what? I’m up here, trying, no matter how drunk we might be right now. We took the time to try and do this, and do I hope maybe someone will like what we do? Of course. It gets nervous; I get fucked up. But when I bother thinking about these Gainesville scenester types, all I can think is: Fuck them. And fuck Ronnie too, if he thinks this is some paradise of music and art. Motherfucker’s just trying to relive college. Because, really, what else does he have?

Finally, our set ends, culminating in a grand finale that lasts twenty minutes, everything this rock and roll fermata, where we try and sound like The Who, windmills and all, only, this time, I would really like to smash my bass guitar and be done with all of this. It’s an endless volley of beer cans from our friends, and I smile, and I do the math, and I think, yeah, I can afford another bass guitar, so fuck it.

I unplug and keep the fermata going on my bass. I walk out of the living room of the Righteous Freedom House, back into the screen door, somehow navigate the three steps to the dirt yard, and I’m still playing the bass even though it’s no longer plugged into the amp, and everyone stops to look at me. I pluck open strings with my right hand and make the devil horns with my left hand, because I know that joke is old and these jerks will hate that as much as they hate The Laraflynnboyles. This is a red Epiphone bass, the only one I have. Six years ago, I worked all summer, busting my ass delivering pizza, to buy the thing. I’ve spent so many hours playing it, in practice, alone in front of the television, or in front of the stereo while trying to learn a new song, rewinding tapes over and over again to make sure I got it right. But I’m feeling this fermata right now more than I’ve ever felt anything. I can’t stand being ignored like this. My anger and frustration with this audience, with my life, with everything, supersedes my attachments, and I raise the bass with both hands, then my right hand wraps over the left hand at the upper neck and I swing downward. The bass guitar makes a funny sound when you smash it into a dirt front yard. There’s a hollow vibration from the wood, from the metal, from the force. I swing and smash and swing and smash as people clear out, some running out to the street, everyone cheering now (they’re cheering), but try as I might, the fucking thing won’t smash. The dirt is too soft, the neck and the body of the bass are too thick. I can’t stop now. I have to destroy this thing. I hear the guitar in the other room stop playing, then an abrupt stop, even the drums stop, and Ronnie and Macho Man Randy stand in the doorway and I’m too fucked up to care how they’re looking right now, and I hold the bass aloft once more and yell to them “Thank you! Good night! And goodbye!” just like fuckin’ Robbie Robertson in The Last Waltz, turn around, run out to the street, and the solid road is all the bass needs to splinter, crack, break until only the strings connect the neck to the body. I’m under a street light, and it’s like I’m under a spot light, and I hear enough “Woo-hoos!” and “Yeahs!” from these dumbass scenesters in the yard to know I’m doing right here, that this makes up for our lackluster set. Victorious, I toss what’s left of my bass towards a drainage grate across the street, where it almost falls into the hole, but dangles on the edge, a little bit short.

And that’s the last thing I remember before waking up outside of Neal’s coachhouse in some lawnchair with Randy sitting next to me as The Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime plays from inside. I come to, ask Randy, “What time is it?”

“2:30,” he says. He punches me on the arm. “How ya feelin’, Townshend?”

At first, I have no idea what he’s talking about, then I remember. The bass. I groan. My heart sinks. I have a nauseous feeling that throbs from my temples to my balls. I lean forward. Hands on my head. I tally the damage. Shotgunned five beers, drank several more, popped five roofies, smashed the bass.

“Think we can fix it?” I ask, knowing the answer. Randy laughs. Yeah. That’s what I thought. I stand, stretch, feel the vertigo and the spinning—the black sky and the palm trees, sand pines, live oaks, closing in, here in Gainesville again, in the patch of dirt separating this coach house from the front house, our cars parked at haphazard angles, as d. boon sings “as I look out over this beautiful land I can’t help but realize I am alone.” I face the street, over and down the small incline of the driveway, the occasional car rolling by, turn around, look into the coach house, where Neal air-drums, air-guitars, air-basses, one after the other, Ronnie behind him, jumping up and down on the couch, William and Paul passing a whiskey bottle back and forth. Neal sees me, yells, “He’s awake!” runs out to me, carrying by the neck the remnants of my bass—the top half of the neck, strings linking the neck to what remains of the fractured body, some wood, some wires.

“This was the greatest thing I’ve ever seen,” Neal tells me, and he hands me my bass, my baby, the only thing in life I care about. “You’re heroes now. Gainesville won’t shut up about it.”

“Well they didn’t show it.” I say, trying to figure out a way to hold what remains of my bass in one hand, without the rest of it either falling into the dirt or swinging into my shins.

“Aw, dude, you know. Extreme times, extreme measures. It was beautiful. Heroic.”

“Whatever,” I say. “Give me a beer.” I shuffle back to my lawn chair.

“You got it, dude,” Neal says, runs in, runs out, hands me an Old Hamtramck. I open it, take one sip, and as Randy starts talking about how it “Looks like Gainesville finally likes us,” I don’t get a chance to tell him why I don’t care and why it doesn’t matter anyway, because the next thing I remember is waking up, face buried between a musty brown couch pillow and musty couch cushion, the evil morning sun broiling and burning through the blinds.

“IT’S THE BEGINNING OF THE END . . . ,” CONTINUED

“Hungover,” Magic answers when Ronnie asks how he’s feeling as they sit at Denny’s before Magic and Macho Man Randy leave for Orlando. Fresh coffees steam out of bottomless mugs. They look out the window next to their booth. The bicyclists and joggers and power walkers of all ages rule the 13th Street sidewalks. The Laraflynnboyles share a communal hatred for the kinds of people who get up to these activities on Sunday mornings like these. “You should move back, man,” Magic continues.

Ronnie shrugs. He isn’t thinking about the band, or moving back. He’s thinking of last night, of Siouxsanna Siouxsanne, of when they finished the show, and suddenly almost everyone decided the band didn’t completely suck, thanks to Magic smashing his bass.

He found her outside, leaning against the back of a car parked in the driveway, a bottle of wine on the roof. They talked. She seemed impressed by what had just happened—and everything about the way she looked was so arty, so practiced and tidy and neat and beautiful, like English women in the alternative music videos girls like Siouxsanna Siouxsanne studied obsessively . . . and Ronnie Altamont, he is none of these things—he is disheveled, his clothes anti-fashion, his hair unkempt and uncombed, and he stood there in post-gig sweat and stink thinking maybe he had a chance because he just did something worthwhile maybe, so he handed her the haiku he kept in his pocket, written on a now-damp piece of scrap paper, the kind of haiku he wrote for every girl he had liked for the past several years, each haiku a variation of any of the following:

“siouxsanna siouxsanne

stunning, let’s go out sometime

so bee-yew-tee-full.”

Siouxsanna Siouxsanne paused to read it.

“Thanks,” she said. “I like this. It’s funny.”

This should have tipped Ronnie off, he now thinks as they sit at the Denny’s waiting for their food. These Florida girls, the way they say something is funny without laughing or smiling so you don’t know if they actually think it’s funny or not. The haiku is always a litmus test. If they laugh at this, they’ll laugh and put up with everything else about Ronnie.

“Well?” Ronnie had asked, suddenly painfully conscious of how sweaty and gross he was, post-gig.

“What?” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne said, reaching over to raise the wine bottle, tipping it to those full red lips, sipping, swallowing.

“Do you want to go out sometime, like, uh, to the museum or something?” Ronnie. So articulate.

“No,” she said.

“No?”

“I can’t,” she sighed. “Sorry.”

“Oh.” Ronnie stepped back, aware of every drop of sweat, every wrinkle in his clothes, the smells. “Ok. Why?”

“Because,” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne said. She extended the arm not holding the bottle and the haiku, palm-up hand moving from side to side to take in the yard and its little groups of talkers. “You’re just like them. Even if you’re not like them, you’re just like them.”

Before Ronnie could say anything else, she walked away, disappearing into the party, into the Gainesville night, and Ronnie now sits at the booth, brooding on what the hell she meant by that. He feels so out of place in Gainesville, especially amongst these people who are supposed to be so different from everyone else. And Magic’s telling him to go back to Orlando.

“It ended up being a good show,” Ronnie says. “We hadn’t played here in a while. Next time we play, it’ll get even better.”

“When we play in Orlando, people just have fun and don’t take this shit so serious,” Randy Macho Man says.

“I don’t get so disgusted I smash my bass,” Magic says, and the mere mention of his now destroyed bass makes him look down, ashamed. Ronnie looks at Magic. Really looks at him. Everything sags anymore. Self-medicated. Severely depressed. A tremendous sadness in the eyes, hidden behind the glasses. “Just waiting to die” was his typical answer to “How are you doing?”

“That was kinda awesome though,” Macho Man Randy says. He can’t wait to get home, to tell everyone about it.

The discussion is interrupted by the egg-shaped waitress, who brings their order—Grand Slam Breakfast for Randy Macho Man, Deli Dinger for Magic, Moons Over My Hammy for Ronnie.

“Just come back, dude,” Randy Macho Man continues. “Orlando’s not as bad as you think.” Every time he comes to Gainesville, Randy Macho Man has a good-enough time, but the complexity of it all, in the way people are always around to tell you what they think and what they heard, when all you need is some friends, a paycheck, a place to go home to with a bong and some records and the Orlando Magic winning on TV.

“It’s worse than I think, and I’m staying,” Ronnie says. “It’s a stupid place, owned and operated by stupid people.”

“Here we go,” Magic says.

“It’s the worst of LA and Altanta,” Ronnie continues. “Seriously. Orlando wants to be Atlanta and LA rolled into one. What kind of an aspiration is that?”

“You’re always complaining,” Randy Macho Man says.

“Totally,” Magic agrees.

The arrival of the food is a relief for Ronnie. The smells of cigarettes and bottomless coffee are joined by scrambled eggs, butter, syrup, cooked meat. Ronnie doesn’t have to fill the silence. He doesn’t have to fill the air with forced conversations no one wants to have anyway.

When he finishes, Ronnie continues, “Look, it’s cool you want me back, but it ain’t happening. I know I’m broke and all that, but I’m . . . ,” and here, Ronnie surprises himself with the word, “. . . happier.”

Happier. Yeah. Happier. “Yeah, you’re happier,” Magic sneers. “You don’t seem happier.”

“I am.” Through the hazy torpor of the late morning hangover, Ronnie smiles. “We can come back and play again, and it’ll go better. People are talking here. It’ll be better. And then we’ll tour. We’re a good band. Good things are going to happen.”

This is met with a collective shrug from Magic and Macho Man Randy during the final bites of yet another post-show Denny’s breakfast. “I’m still getting the tour going. It’ll be fun to get out of the state for once.” Another collective shrug.

They pay the bill, walk out into the heat, to Macho Man Randy’s car.

“Alright, well, we’ll talk soon,” Magic says, getting into the car.

“Yup,” Ronnie says.

“Later,” Macho Man Randy says, and that’s it.

I.D. 4: THE HOLIDAY (NOT THE MOVIE)

In the early morning hours of the 5th of July, Ronnie, passed out in the backseat of his car, awakens to the sounds of tremendous farting, like stubborn old lawnmowers refusing to kickstart.

Ronnie opens his eyes, disoriented, unsure of where he is, and then he sees—no, it can’t be that—two pairs of hairy white ass cheeks, pressed against the windshield as Neal screams, “Ronnie Altamont! Wake up, dude!” while his brother Paul laughs maniacally on the passenger side of the windshield.

Ronnie sees, hears, and processes what is happening, yells “Oh Gahhhhhhd!,” the bile rising in his chest. He opens the car’s back door and runs to the backyard of the barbeque he had been at since noon yesterday, puking into shrubs two bottles of Strawberry Kiwi Boone’s Farm (Strawberry Kiwi Boone’s Farm? What is he, thirteen?!), vomit like yogurt and power steering fluid. Behind him, laughter, growing closer, louder.

“Altamont!” Neal hollers, rounding the corner of the house. He sees Ronnie, bent over, coughing and drooling. “What are you doing?”

Ronnie rises, stupidly drunk but sober enough to know how stupidly drunk he has been. “I didn’t move here to have the banal college experience of puking at some party,” he announces, an attempt at sounding smart. Only the thing is, he believes it. Because the college aspects of life here, to interact with college people as they do their college things (and not the music things, the art things, the you-know punk rock things) fills Ronnie with a cold desperate desire to leave immediately, and to puke like this reminds him that his time in Gainesville is limited, because this simply cannot go on.

On the other hand, Ronnie isn’t sure if a pair of brothers farting with their naked asses smooshed against a windshield constitutes “banal,” but his cheap-wine-soaked mind isn’t really up for such fine distinctions. He falls to the ground again, retches.

“Seriously!” Neal yells, then repeats, “What are you doing?”

Paul follows his brother, watches Ronnie bent over the shrubs, says, “Alright, Altamont. Get the last bit out. You’re better now. Let’s get back to the party and get you a beer.”

Ronnie stands, wipes his mouth, nods. He looks away from the shrubs, to Paul and Neal. Neal is completely naked. It’s that time of the night for Neal to be completely naked, Ronnie thinks. Paul readjusts his pants. Ronnie wants to throw up again, but merely dry-heaves. That image. Two pairs of asscheeks pressed against the windshield. Oh Gahhhhhd. Half-awake, with the brain ache where the lost inhibitions used to be.

He walks back around the house with Paul and Neal, past his car, to the front yard, as Paul and Neal laugh heartily. From the rest of the party, Ronnie is greeted by tipsy applause from the people who remain—names Ronnie learned and unlearned in a matter of seconds, sitting around the faintest embers of the grill, pulling out fireworks from backpacks.

“Lesser men have died seeing what you just saw,” William says, handing Ronnie an ice cold Dusch Lite. Everyone laughs. Ronnie manages a smile. Ronnie opens the beer. That is the closest he gets to drinking it.

Later he sits in a lawnchair and tries piecing together what happened as almost everyone else runs out onto the street to do battle with bottle rockets. Five to a side, they crouch behind mailboxes, cars, trees, light the wick, the seconds of waiting, the scream, the whiz, the explosion, the laughter, the screams of pain, of triumph, the smoke trails, that acrid firework Independence Day stench. In out-of-sequence images, Ronnie recalls showing up thinking it would be funny to be the guy with two bottles of Strawberry Kiwi Boone’s Farm, drinking them from the bottle, quickly, because he is nervous, surrounded by all these people he does not know, who circle the grill with beer and whiskey and the kind of languid summertime conversation you hear once all small talk and latest news has been exhausted. There was Siouxsanna Siouxsanne, as drunk then as she is now, not at the bottle rocket fight but walking around yelling “We’re not friends anymore, assholes!” to the warriors fighting on the street, no one listening because she says this every weekend and they find it endearing, somehow. In a social scene filled with quirks, kinks, and eccentricities, this is what Siouxsanna Siouxsanne does. Oh, and Ronnie remembers William, at one point, taking Ronnie aside and asking, “You all right? You seem a little quiet today.”

“Uh, yeah,” Ronnie managed, numb, not fully there. The alcohol shut him down, rather than animating him.

“You should eat something, dude,” and William pointed to a blackened paper plate next to the grill, piled with charred soy hot dogs. “Cool,” Ronnie answers, yawns, and shuffles off to the back seat of his car where, on the floor, an old copy of the school newspaper, where Ronnie studies the cartoon from Maux (he tries remembering where he had heard that name) of a pantsless hillbilly straddling the Florida panhandle as the rest of the state dangles between his legs like a limp penis. Inside the state penis are tiny drawings of New Yorkers fighting Cubans fighting tourists fighting surfers fighting rednecks fighting state troopers fighting the elderly. As an added touch, the Florida Keys drip like urine from the bottom. Everyone holds a pointed gun. The caption reads, “Greetings from Florida,” drawn in postcard lettering. “Try not to get killed!” The postcard was tilted sideways to look like it was pinned off-kilter to a bulletin board. Ronnie smiled at it, thinking of how unpleasantly funny—and uncollegiate—such a girl must be who would draw something like this.

This is all Ronnie remembers before waking up to Paul and Neil’s asses and thunderous farts.

“I absolutely hate these people,” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne says, stumbling around the grill. “Farting on windshields? Shooting each other with bottle rockets? I don’t know why I bother trying to be friends with anybody here.”

“Yeah,” Ronnie says, rubbing his temples, thinking of his bed, or the stacked mattresses in the tiny trailer bedroom that passed for his bed.

“Why are you here?” Siouxsane Siouxsanne asks.

Ronnie looks up at her. “You kinda look like Nico. Anybody ever tell you that?’

“Yes,” Sioxusanna Siouxsanne says. “Now answer the question.”

“Aw, man,” Ronnie says, in a weary way, like Dylan in an imagined press conference. “Because it’s the Fourth of July, and . . . ”

“No,” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne stops, stares at him. “Here. Gainesville. You’re not going to school here. So why bother?”

Ronnie looks away, throws up his hands, mumbles, “Aw dude, I don’t know.” He shifts in his chair, drunk enough to throw out, half-serious, to the empty windless air, “To meet girls like you.”

Surely, in this giant world where all possible outcomes have already occurred, there have been plenty of moments of ill-timed vomiting, but Siouxsanna Siouxsanne, not triggered by Ronnie’s words, but by all the drinking, those pills (whatever what’s-his-name gave her), this all-encompassing weariness and wariness with Gainesville and these parties and these people, moans and moves, scurrying to the back of the house to throw up in the very same suffering shrubs covered in Ronnie’s violent earthtoned regurgitations.

“Jesus,” Ronnie mumbles, over the steady din of the unceasing bottle rocket war, “When I tell women I like them, they puke.” He leans forward, regains his footing in that awkward precarious way people do when they rise from lawnchairs, trudges to the backyard, where, thankfully, Siouxsanna Siouxsanne has found shrubs past Ronnie’s defiled shrubs, seemingly free of what Kerouac once called “sentient debouchments.”

“This isn’t about you,” Siouxsanna Siouxsanne says between violent retchings. “You’re ok . . . Just don’t ask me out anymore.” She coughs, spits. “See you later.”

Ronnie needs to leave. He walks back to the side of the house, to his car, to the front seat this time, Siouxsanna Siouxsanne’s puke-cough fading away, the moon and stars spinning, trapped in the eyeache of a cheap wine hangover. Ronnie pulls out into the street, honking, smiling, waving at near-strangers as he weaves through one side of the bottle rocket war. Fireworks bonk the trunk and rear window, faded laughter decrescendos into the silence in the emptiness of the student-ghetto streets, and Ronnie drives home, listening to Gary Numan sing “Me! I Disconnect from You,” and Ronnie wants to feel alive, and he could almost turn around and tell Siouxsanna Siouxsanne that that is the reason he lives in Gainesville now. Not to feel younger, or to extend the first taste of adulthood freedoms via the college lifestyle, but to feel alive. He could turn this car around and tell her this, but Ronnie knows this isn’t a pressing concern for Siouxsanna Siouxsanne right about now, assuming she even remembers the question.

EATING BAKED POTATO WITH A JELL-O STRAW

Mouse stands before Ronnie Altamont and Icy Filet, wearing a tattered brown and green bathrobe, holding a cassette tape, smiling that smile, preparing to speak. Ronnie has just met Icy Filet, having come to Mouse’s to escape that depressing trailer, where maggots collect on the rotting food left in the kitchen before transforming into dozens and dozens of flies, where the summer smells have taken on a humid raunch, where the shade of the Sherwood Forest trailer-trees cool nothing.

“Icy as in, you know, cool, and Filet, as in, you know, our state’s abbreviation?” Icy Filet had explained to Ronnie when she greeted him at the door in an oversized faded green button down long-sleeved shirt, stained and torn and obviously belonging to Mouse, shirt hung low like a miniskirt, exposing squat legs and bare feet tromping through the dirty kitchen to the perpetually cluttered living room, where they sit facing the mammoth speakers ten feet away, with Mouse in between, preparing to speak.

“Welcome, Ronnie. Now, as you know, I’ve been trying to write a hit song, something that will get on the airwaves. Something commercial. Something lucrative.” Between right index finger and thumb, Mouse raises the cassette to his face. “This, my friends—this!—is the song.” He steps to the stereo, left hand holding the cassette outward, right hand behind his back, looking down like a professor reaching the apex of a lecture he knows is brilliant. He dramatically turns to Ronnie and Icy Filet, points to Icy Filet, who sits “Indian-style,” tugging at the shirt she wears. “But with this here lovely lady,” and Mouse steps to her, leans down, kisses her on the barrette holding the frosted highlights of the ruby-dyed left-parted short hair; Icy Filet smiles, a ruby lipstick smile stretching across her face, and looks away, adjusting her cat-eye glasses. Mouse returns to the stereo, bookended by the mammoth speakers, “. . .we have the makings of a hit song, something with what they call in this business of music, crossover appeal. So without further ado, let’s hear our song, and Ronnie, I look forward to seeing you blown away by this, and I look forward to hearing your thoughts.”

Mouse turns, inserts the cassette, presses play. Foreboding tape hiss, then screeching white noise, followed by a slow synthetic 4/4 hip-hop beat—bass drum, snare, closed high hat cymbals opened on the eighth note after three then closed at four—repeated. A simple four note bass line on an endless loop, and then Icy Filet’s voice, an awkward, lurching, talk-speak that doesn’t quite lose the rhythm no matter how hard it tries:

I’m in my room watching Sanford and Son

faking heart attacks, Elizabeth it’s the big one

drunk like Grady workin’ power saws

eatin’ baked potato with a Jell-O straw

we got astrophysicists down the hall

German swimmers and people throwin’ Nerf balls

aphrodisiacs circled on my plate

do I have free will or is everything fate?

As the verses stop, the beat continues—the bass line, the white noise guitar—as Icy Filet interjects “Word” and “Aw yeah” here and there. The next verse:

Floridian Wizard of the rhyming scheme

Icy Filet is everything she seems

sortin’ it out in a laundry bag

chicken fried rice and a can of Black Flag

roaches on the ceiling fishing for the sounds

of Icy Filet, Mouse, and the Get Downs

candy apple bottom with a tig ol’ bittied face

like a Sharpie in your mind that can never be erased

The song soldiers on for five more seconds until the beat stops. The white noise of the guitar fades away into the tape hiss. Mouse stops the tape.

“Well?” Mouse asks, leaning in towards Ronnie, that insistent smile and subtle nod simply begging Ronnie to say it was anything less than completely brilliant.

It is ludicrous, awful, stupid, terrible, cheesy, moronic, sub-par, puerile, painful, insufferable, not-good. Ronnie clears his throat. “Completely brilliant!” he proclaims, smiling. “It sounds a lot like Beck.” (In Gainesville, it is always important to tell everyone what you think everything sounds like. It shows you know what you are talking about.)

“Beck?” Icy Filet leans backwards, lightly pounds Ronnie with her tiny right fist. She pshaws. “That’s bogus, yo. I mean, I like him, but that’s not what I’m going for. I want to be whiter than Beck, if that’s possible.”

Mouse removes the cassette from the stereo, places it back inside its case, tosses the case aside, near a stack of yellowed underwear. “We’ll go back to it. It has potential. Ronnie thinks so. Right, Ronnie?”

Ronnie smiles a charming used-car-salesman smile. “I do.” Yes, Ronnie believes the song is horrible, but he also believes that, in a perfect world, songs as amateurishly strange as these would be the staples of commercial radio and played with the same unceasing regularity as Pink Floyd.

“Good,” Mouse says, readjusting his bathrobe, a wavy flick of the wrist preventing encroaching nudity.

“What do you do, Ronnie?” Icy Filet asks, as they rise to stretch, to step out of the slovenly living room.

“He does nothing!” Mouse says, stepping into the kitchen. “It’s why he has no money!”

“I’m a writer,” Ronnie says. “I’m also a musician.” They follow Mouse into the kitchen, where Mouse opens three green-bottled beers while howling and laughing, “He doesn’t write! His band is a hundred miles away so they never play anymore!”

“That’s not true,” Ronnie says, grabbing one of the cold green beer bottles from Mouse, chugging, mulling the idea that Mouse is probably right. Yes, probably.

“Mouuuuse,” Icy Filet whines a scold to her newish boyfriend of two-and-a-half months, who looks as hangdog as a guy who looks like Charles Manson can look. She turns to Ronnie, puts her arm around him. “It’s ok. I believe you’re a writer. Do you believe I’m a rapper?”

Ronnie smiles. He can’t say “No,” no matter what he really thinks. “Yes. I do.”

“Thank you,” Icy Filet says, hugging Ronnie before grabbing the beer from Mouse’s outstretched arm. “You look hungry, Ronnie. Let me order us some pizza. How does that sound?”

“Of course!” Mouse laughs. “Ronnie doesn’t eat much, and he needs to.”

Ronnie could not disagree. The money is gone. He would be four months behind on rent, if Alvin bothered collecting the rent, to say nothing of the other bills. Ronnie tends to blow the plasma money as soon as he gets it—on beer, on eating out, on enough gas to get to some party and back. He is tired, hungry, exhausted, can’t think of tomorrow, or the day after that, and definitely not next week, and don’t even mention next month. In the Sweat Jam life, you take whatever resources are at your disposal at that immediate moment and use them to your fullest advantage, to suck the most fun you can out of that moment, because, tomorrow? You will be tired, hungry, exhausted.

When the pizza arrives, Ronnie’s hunger pangs temporarily retreat. He finishes the beer and eats his fill, walks into the living room, finds the cassette case dangling at the edge of the dirty underwear pile, removes the tape, places it in the stereo, hits play, then stretches out across the long-unvacuumed floor, falling asleep to the music of his friends, deep in the sleep of one who is exhausted doing absolutely nothing with his life, and having a wonderful time doing so.

WHAT PART OF “DON’T LOOK BACK”

DON’T YOU UNDERSTAND?

Kelly stands in the threshold of the opened front door, watching the sprinkler’s jets slowly rise, prismatic droplets refracting the sun before splattering across his crunchy parched brown lawn. He lives in the back of a 1950s subdivision in a tiny, pastel blue cinderblocked one-story house in a large corner lot. Across the street, a massive water tower hovers over everything like a UFO on the verge of shooting lasers at unsuspecting earthlings in some long-forgotten drive-in movie. High fences topped with barbed wire thick as bass guitar strings cordon off the opposite side of the street, separating the construction workers, plumbers, and mechanics who live in the neighborhood from the University of Central Florida Research Park on the other side.

Under the driveway’s silver awning, a gray Volkswagen Rabbit is parked with its hood opened, perpetually awaiting whatever repair it needs to return to life. Next to the Rabbit is a brown Chevy Celebrity, jack propping up the left front tire side, also perpetually in wait for the repairs that will/might return it to the roads. In front of these on the driveway, Kelly’s still-functioning rusted maroon Nissan truck. A blandy apple green four-door sedan rolls up and stops inches from the truck’s downward angled rear bumper.

Ronnie shuts off the car, steps out, awaits the inevitable “Told ya so” from Kelly.

Instead, without taking his eyes off the withered brown grass, Kelly sighs, announces, “Take what you want to make sandwiches. There’s beer in the fridge too.”

Ronnie nods, fifteen footsteps a brittle crunch across the grass, stepping around Kelly, then entering the house. Over the sprinkler’s spray, Kelly hears the opening of a beer can, the frantic rattling of glass containers, the rustling of wrapped deli meat. Shortly after this, the sounds of The Incredible Shrinking Dickies album on the stereo. Loud.

Kelly continues watering what remains of his lawn, wondering if anything will ever change, or if life will always go on like this, surrounded by friends living a hand-to-mouth existence filled with one or all of the following: beer, dope, acid, Xanax, roofies, mescaline, ecstasy, heroin. Time measured between shows, the once or (if we’re lucky) twice a month wait, filled with work, sleep, then any or all of the preceding. Kelly watches Ronnie step out the door, a beer can in each hand, draining the first, opening the second. He is much thinner. Disheveled hair, not in the fashionable sense, but in the “two weeks in a Greyhound Bus terminal” sense. The pungent, musty smell of unwashed clothing.

“Jesus, Altamont,” Kelly says, stepping back. “What the hell up and died on you in Gainesville?” He takes another step away, scrunching his gaunt face in disgust. “Besides your soul?”