FOREWORD

“The government of Canada only understands the 26 letters of the alphabet.”

– GARRY GOTTFRIEDSON, SECWEPEMC POET AND HORSE BREEDER

When Garry Gottfriedson made his remark in Salmon Arm, he was explaining the integral roles his parents had played as activists in the movement that resulted in the ascendancy of their Shuswap leader George Manuel. I jotted it down without thinking. It had a ring to it.

Now it serves as a succinct explanation as to why this book exists. As Gottfriedson realized, in Canada we fight mostly with words. In that context, the growing English language proficiency of First Nations people—and their ability to persuasively use those “26 letters of the alphabet” on paper—has generated a literary movement of immense importance.

In British Columbia, where the country’s first Aboriginal-owned and -operated publishing company was founded in 1980, the recent proliferation of books for, by and about Aboriginals—the term used in the Canadian constitution to designate “Indians,” Inuit and Métis—merits documentation and celebration.

Aboriginality, volume two of “The Literary Origins of British Columbia,” introduces more than 170 Aboriginal authors (including painters, carvers, illustrators and editors) who have produced three hundred books since 1900.

Garry Gottfriedson

These authors are arranged mainly chronologically, in terms of their first published works, rather than alphabetically or in accordance with tribal origins (often mixed), geography or literary genres (often mixed). This approach allows for easy appreciation of changing themes as well as the surge of literary activity that was spurred by the appearance of a viable B.C. publishing industry in general, and the establishment of Theytus Books, founded by Randy Fred, and the En’owkin Centre, overseen by Jeannette C. Armstrong, in particular.

In our newspapers we frequently learn about the hard-won progress made by Aboriginals through our legal system, and we have recently benefited from a surge of more than one thousand British Columbia-related books pertaining to “Indianology”—the study and marketing of First Nations culture—but the uprising of literature from Aboriginals in B.C. has seldom been celebrated or even cited.

Aboriginality is the first attempt in book format to identify the books by First Nations peoples in B.C. or, for that matter, in any Canadian province. I hope this assembly of biographical, cultural and bibliographical information amounts to cultural news.

I have limited my definition of literature herein to books. Others are welcome to expand their definition to include oral storytelling and petroglyphs (both subjects for many books already.) A separate entry is accorded to each author. As Aboriginality is intended to introduce a wide spectrum of (mostly) hitherto unknown Aboriginal writers, it seemed important not to subdue individual writers and their books to any overarching theme.

As with the first volume in this series, an extensive bibliography is provided. There is also an index of authors. To the alarm of one reviewer, extracts of volume one (and now volume two) can be easily copied (at www.abcbookworld.com). My goal is to disseminate useful information. Most people know precious little about the literary history of British Columbia and I have always preferred to write for most people.

A word on terminology: in a province where the majority of people are from somewhere else, and change is coming quickly to many Aboriginal communities, it is difficult to get everyone on the same page about specific names used to describe First Nations people and places. Haida Gwaii and the Queen Charlotte Islands have become interchangeable terms. Do you prefer Interior Salish, Thompson Indians, Niakapmux or ’Nlaka’pamux? Should we write Gitksan, Gitxsan or Gitxsan?

I am not a schoolteacher whose job it is to change the spelling of others, or a geographer with the power to alter the world atlas. This book was written in English, not Haida or Kwak’wala. Nevertheless, in a place where nearly everyone has learned to pronounce Tsawwassen with a silent T, I hope we can continue to embrace linguistic diversity. I leave the literary policing to others.

It should also be noted that writing in English by Canada’s Aboriginal peoples, who favoured an oral culture for millennia, is a relatively new phenomenon. Less than one hundred years ago, most tribes in British Columbia were dependent on the services of intermediaries such as James Teit, the conciliatory Peter Kelly (who supported the government ban of the potlatch), or white missionaries, to represent their viewpoints in print.

A reluctance by Aboriginal communities to adopt English was understandable. Obviously one way to preserve indigenous culture was not to conform to the dictates of so-called white society. Hence literacy in English was seen as a double-edged sword: it gave individuals greater resources within the mainstream society, but literate Aboriginals were more prone to leave the reserves and thus lose their traditional values and way of life.

As well, those Aboriginals who are willing to credit the deservedly maligned residential school system for teaching them how to read and write the English language tend to do so quietly. Memories of residential schools cut deep. In a nutshell, the learning of English has been connected to cruelty for generations. Hence the advent of published Aboriginal authors in British Columbia as a new “norm” in our society represents a painful triumph of both will and endurance.

To this day, Aboriginals who earn university degrees are sometimes not fully trusted within their own tribes. Arguably, they have “gone over to the side.” In some cases, they are even discriminated against.

For earlier Aboriginals, the English language has been a burden and a curse to be overcome, slowly, and with caution, rather than a system of communication that could be taken for granted. One early example concerning events arising from the so-called Chilcotin War illustrates this fear of the written word.

Once upon a darker time, when the written word was used as a tool of oppression, the Reverend R.C. Lundin Brown, a clergyman at St. Mary’s Parsonage in Lillooet from 1863 to 1865, described his efforts to convert six Tsilhqot’in (Chilcotin) men who were sentenced to hang by Judge Matthew Begbie in the aftermath of violence in April of 1864. While defending their territory near Bute Inlet against the incursion of road builders who had verbally threatened them with the advent of a smallpox epidemic if they did not cooperate, the Tsilhqot’in had killed 14 intruders.

The Reverend Brown wrote: “They have, be it observed, a very special horror of having their names written down. They look upon paper as a very awful thing, they tremble to see the working of a pen. Writing is, they imagine, a dread mystery. By it the mighty whites seem to carry on intercourse with unseen powers.

“When they are writing, there’s no telling what they may be doing. They may be bidding a pestilence come over the land, or ordering the rain to stay in the west, or giving directions for the salmon to remain in the ocean.

“Especially is the Indian appalled when he sees his own name put on paper. To him the name is not distinct from the person who owns it. If his name is written down, he is written down: if his name is passed over to the demons which people his hierarchy, he is sure to be bewitched and given as prey into the teeth of his invisible foes.

“So when those Chilcoatens [sic] saw their names taken down and heard themselves threatened with disease, they were only too ready to believe the threat…. Had not the Shuschwaps [sic] lost many of their warriors? and the Indians who lived away at Lillooet, on the great river, as many as two-thirds of their whole tribe?

“It was only too likely that those awful whites would fulfill their threat, and send the foulest of all diseases which ever came forth from the jaws of hell, to sweep their tribes away into everlasting night.” So in the beginning was the Word—as well as guns, Bibles, booze and disease.

Whereas the literary activity charted in Aboriginality spans approximately a century, the backdrop for Aboriginal storytelling stretches back at least ten thousand years. Some acknowledgement of that expansive cultural legacy, from which a new literary culture has only recently emerged, seems necessary.

The oldest known site of human habitation in British Columbia, the Charlie Lake Cave near Fort St. John, contains tools, bison bones and jewellery, radio carbon-dated to 10,500 years ago. The oldest skeletal remains belong to a young male caught in a mudslide at Gore Creek, east of Kamloops, approximately 8,300 years ago. These bones were recently repatriated for interment in Secwepemc territory.

One of the largest prehistoric village sites in Western Canada is at Keatley Creek, about 20 kilometres upstream from Lillooet, where approximately fifteen hundred people resided in more than one hundred houses between ten and twenty centuries ago.

And then came the newcomers. The first verifiable meeting between Aboriginals and Europeans within what is now B.C. territory occurred near Langara Island, at the north end of the Queen Charlotte Islands, on July 19, 1774. Three canoes approached the Spanish ship Santiago under the command of Juan Pérez at around 4:30 in the afternoon. Captain Pérez, his second-in-command Esteban José Martínez and two Catholic priests recorded the meeting in their journals.

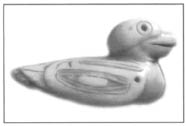

Bird amulet collected by Juan Pérez in 1774

One of the Spanish officers tossed a biscuit, wrapped in a kerchief, into one of the canoes. Eager to barter, and having learned the value of metal from Russians to the north, the tribe (likely Haida) traded fish for beads and returned the following day, about one hundred of them, in more than a dozen canoes.

That day Juan Pérez acquired a painted bird amulet, to be worn around the neck, “with a string of teeth that appeared to be those of a baby alligator.” Made from a whale’s tooth, this carved amulet—one of the oldest artefacts from B.C.—is on display at the Museõ de America in Madrid.

Among the items acquired by Aboriginals during Pérez’s two known anchorages—the other near the entrance to Nootka Sound—were two Spanish spoons. These two eating utensils (“evidently not English make”) resurfaced as significant trade items in 1778 when Captain Cook arrived at Nootka Sound with his subordinates William Bligh and George Vancouver. The purchase of the two spoons by a British seaman aboard the Resolution—as recorded in four British memoirs of the voyage—was later cited by the Spanish to prove the British were not the first Europeans to reach British Columbia.

Eagle mask collected during Captain James Cook’s visit to Nootka Sound in 1778

The complicated relationships between Chief Maquinna’s people at Nootka Sound and the flurry of British, Spanish, French and American mariners in the late eighteenth century have been recalled in First Invaders: The Literary Origins of British Columbia, the predecessor to this volume.

George Clutesi was bequeathed the brushes of Emily Carr.

Since the arrivals of Pérez and Cook in the late eighteenth century, Aboriginals have had minimal impact on the process of formally recording British Columbia history on paper.

For most of the twentieth century, the best-known Aboriginal authors were celebrated as Indians first, writers second. Pauline Johnson was a theatrical recitalist who lived in Vancouver for only four years. Chief Dan George was primarily an actor. George Clutesi was regarded as a painter, actor and broadcaster.

Prior to the 1980s, most books credited to Aboriginal authors were of the “as told to” variety. As Aboriginality reveals, a surge of literary activity began as Aboriginals themselves learned to take control of the means of production. An urbane uprising of self-confidence occurred. This change is reflected in the contents of Aboriginality.

From the early 1980s onward, the literary climate for Aboriginals in British Columbia has been changing rapidly, prompted by Aboriginal publishing and the nurturing of writers at the En’owkin Centre in Penticton. Accordingly, “Voices from the Wilderness,” the opening section of this book, concludes with the establishment of Theytus Books in 1981, leading to “Seeing Red,” marked by the publication of Jeannette Armstrong’s first book. A third section entitled “Artists and Carvers” includes individuals not primarily known for their literary activities, followed by 55 condensed entries for “Also Noteworthy.” The bibliography is restricted to titles written or illustrated by Aboriginals.

My father grew up in West Vancouver with Indian friends, but gradually these family friendships disappeared until a virtual apartheid ensued.

I learned to say a few words of Chinook and I wore Cowichan Indian sweaters to school, but my contact with the Aboriginal community in West Vancouver was restricted to rare soccer games on the Capilano Indian Reserve where their pitch was bumpy, their players were athletic but disorganized, and the games were rough. There was never any fraternization afterwards beyond a grudging handshake.

Since then we have been making some hard-won progress. As a society, we are collectively making some amends; we are slowly getting reacquainted.

Aboriginal people currently comprise approximately 4.4 percent of the B.C. population according to a StatsCan 2001 survey, but their distinct histories and their imaginative universes can have enormous significance for anyone who can look beyond their television set.

As a fifth-generation Vancouverite, I want to understand better how Aboriginal societies are integral to where I live. A follow-up volume is being prepared to address the remarkable range of more than one thousand titles pertaining to B.C.’s First Nations and written by non-Aboriginals, but it struck me as appropriate to present first the emerging field of B.C. Aboriginal writing, a hitherto unmarked literary zone

Most tribes did not sign treaties in B.C. They did not legally relinquish their territories. Therefore all British Columbians are challenged by a morally perplexing history. If we have inherited social problems, they need to be fixed. Cumulatively the pain and poverty, the prejudice and persecutions of the past cannot be expunged, but at least the past can be fully acknowledged.

The notion that the Aboriginal peoples of this province are the original peoples of this province with distinct societies, and that they deserve to be “citizens plus” (to borrow a term from Alan C. Cairns and Harold Cardinal) because they were “citizens minus” for so long, still appears seditious to some people. And yet progress at reconciliation is being made, even among those for whom the “nation-to-nation paradigm” is problematic.

Some 72 percent of British Columbia’s Aboriginals are now living in urban environments, not on Reserves. According to Madeline MacIvor of the First Nations House of Learning at UBC, a significant portion of these are leaders in the struggle to redefine the place of the Aboriginal community in Canada. Within that process, British Columbia leads the way in Aboriginal literature.

In the words of carver and photographer David Neel, “Today we are witnessing the rebirth of our cultures on the Northwest Coast. We can see the end of a period of oppression, and we can see a time of hope for our grandchildren. We are entering into a time in which Aboriginal people have a place in contemporary society. The Native has learned much; it is now time that society learn from the Native.”

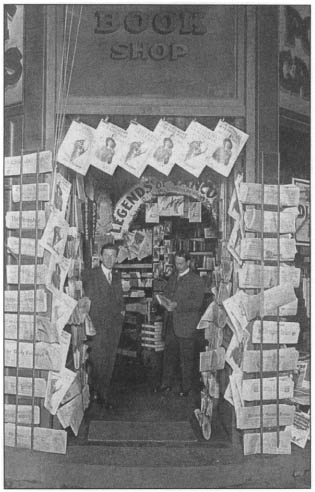

Publisher G.S. Forsythe sold Legends of Vancouver by E. Pauline Johnson from his bookstore at 349 West Hastings (circa 1913).