Watching the six large tapestries being hauled into place on the walls of the museum’s Grande Galerie in the spring of 1883, Edmond du Sommerard probably stroked his extensive beard and breathed a sigh of relief. It had, by all accounts, been a difficult negotiation.

The wall-hangings, sumptuous, enormous rectangles of colourful wool and silk made in Flanders in the final years of the fifteenth century, had first been discovered forty years earlier, in 1841. The writer and Inspector-General of Historic Monuments, Prosper Mérimée, had found them at the Château de Boussac, an imposing renaissance mansion in France’s central region of Limousin. But it was hardly a grand enough residence for works that, half a century later, would rival the Mona Lisa as one of Paris’s star museum attractions. Mérimée was horrified to discover that several parts of the extremely rare tapestry series had already been cut up by the local administrators of the château and used to cover carts or furnish the house as carpets and doormats.

By 1882 dwindling funds had forced the town of Boussac to put the tapestries up for sale. The remaining pieces were found damp-stained, nibbled at their corners by an undiscerning mouse, but their value was still clear to those in the know. The notorious rumour mill of Paris’s flourishing antiquities market started firing on all cylinders. Hushed conversations over account books spoke of substantial private offers, upwards of 50,000 francs, double the price for which the château itself had recently been purchased. Speculation was mounting, too, that the tapestries had caught the eye of a mega-collector, perhaps the wealthy banking scion Alphonse de Rothschild, and were poised to be vacuumed up into the private market, disappearing from public view for ever.It was only after heated talks and the intervention of the French state that Boussac agreed instead to sell the tapestries to the Musée de Cluny in Paris for a more modest sum of 25,500 francs.

The museum had been the brainchild of Edmond du Sommerard’s father, Alexandre, an influential figure in the revived taste for the medieval among the cultural movers and shakers of the capital. By 1833 his collection of medieval and renaissance objects had become so large that he was forced to move them to bigger premises in the extravagant late medieval mansion known as the Hôtel de Cluny, just a short walk south from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame and the Île de la Cité. But Alexandre made it clear that his pieces should not be cloistered away for ever. Upon his wishes, after his death in 1842 the Hôtel was converted into a public museum, so that Parisians of all classes could be transported back into France’s medieval past. His son Edmond, the museum’s first director, restored and refigured the building, extending it to include a new long salon upon whose walls the tapestries were finally hung.

More than a century later these intricate textiles are still on public display at the museum, now known as the Musée national du Moyen Âge, where they were carefully restored in 2013. Yet although the softly glowing lustre of their rich coloured cloth has been revealed for the first time in over 500 years, people are still puzzling over what precisely they depict. Each tapestry carries an intricate design featuring a young woman, a lion and a unicorn. They vary slightly in size, presumably to match the medieval walls they would have originally decorated and insulated, but across all six pieces the same trio adopt different poses and positions in a fantastical circular green garden. Their surfaces are everywhere puckered with sprouting wild flowers, hiding frolicking miniature creatures and supporting stout trees of crisp, bushy leaves laden with different varieties of blossoms and fruit. This cornucopia would have been quite a showcase for the immense technical skill of their Flemish weavers, who would have painstakingly transformed the designs from painted cartoons into woven cloth. The woman herself, though, is enigmatic. Sometimes standing and sometimes seated, sometimes aided by a younger maid and other times alone with her beasts, she gestures back and forth between tasks in a language of subtle signs, a pointed finger here, a soft caress there. The heraldic flags that feature prominently throughout the series feel like they might offer a clue to who she is, or to the tapestries’ original commissioner, but the specific symbolism of their three crescent moons has been lost over the centuries. We have no immediate access to what this young woman is saying or doing or thinking, or to the scene of the action itself: her island is enclosed, floating in a deep-red vegetal background some distance from any world that the viewer inhabits.

One thing does seem to be clear about the tapestries, however. Across the first five compositions the woman treats the lion and unicorn to the music of her harmonium, feeds her parrot and a monkey from a bowl of berries, sniffs a wild flower, tenderly touches the unicorn’s horn and plays with a mirror: displays of hearing, taste, smell, touch and sight. Classical and early medieval authors had once worked with a much more open understanding of what constituted a sense, including the brain’s faculties such as memory and the imagination, or extreme feelings like anger and divine love. But by the later Middle Ages the traditional ‘Five Senses’ had solidified as the five fundamental forms of sensory interaction that could take place between bodies and their immediate environment. To explain the working of these senses, thinkers of the period sought to understand the base matter behind each and how it moved throughout the world: how a flower’s perfume might be borne on the wind, or how sounds made their way through the air. But, crucially, to get to the heart of sensation they needed to know how these sensory signals were received by the body itself.

Seeing Sight

In one of the largest of the Cluny tapestries the young woman turns a gilded mirror towards the smiling face of her unicorn, casting his image back in miniature towards the viewer. Among her elaborate surroundings, flashing the face of her companion seems a small act for the woman, nothing more than a twist of the wrist. But in inviting the unicorn to see its own reflection in this way, she also asks us to consider the very mechanics of looking itself.

Two contrasting theories of sight jostled for primacy in the Middle Ages, both of which understood the sense to function through the exchange of light. The first took up the notion that the eyes fundamentally functioned as receptors, accepting visual rays that were cast outwards from all objects in the world and conveying this sensory information back to the brain via the optic nerve.Supporters of this theory of intromission, as it was known, ranged from Aristotle to Ibn Sina, who strongly upheld the idea in his Danish-nama-yi ‘Ala’i ( commonly called ‘The Book of Scientific Knowledge’). ‘The eye is like a mirror’, he argued, ‘and the visible object is like the thing reflected in the mirror’. The second, competing idea of vision also developed from classical writings, especially the Greek theoretician Euclid and the Roman writer Ptolemy, but conceived of sight as functioning the other way round. It was not objects that projected light, they argued, but the eye itself that expressed rays outwards until they alighted upon an object. Sight in this mode was an almost tactile process, with invisible emissions from the eyes feeling their way through space to illuminate the world with their diaphanous touch.

commonly called ‘The Book of Scientific Knowledge’). ‘The eye is like a mirror’, he argued, ‘and the visible object is like the thing reflected in the mirror’. The second, competing idea of vision also developed from classical writings, especially the Greek theoretician Euclid and the Roman writer Ptolemy, but conceived of sight as functioning the other way round. It was not objects that projected light, they argued, but the eye itself that expressed rays outwards until they alighted upon an object. Sight in this mode was an almost tactile process, with invisible emissions from the eyes feeling their way through space to illuminate the world with their diaphanous touch.

Medieval writers continued this nearly millennium-long debate about vision’s directionality until the 1260s, when the English theologian and author Roger Bacon (c.1220–1292) intervened to suggest that, in a way, both camps might be right. In a subtle synthesis of the two visual traditions Bacon’s highly influential book on the philosophy of optics, the Perspectiva, argued that the optic nerve did indeed relay sensations of the eye to the cognitive faculties of the brain, but that it could both send and receive information. Sight, therefore, could be based in both objects and bodies, and natural philosophers of all stripes appeared convinced that visual rays moved both into and out from the eyes in two directions, not just one.

14. A diagram of the eye from an Arabic treatise written by the Nestorian Christian scholar Hunayn ibn Ishaq, itself a ninth-century translation of Galen’s even older treatise on ocular remedies.

Medieval opinion was similarly fluid about the physical make-up of the eye. On the one hand, its theoretical anatomy had been relatively consistent for centuries. When physicians described it in their treatises, they spoke of a circular organ with a lens at its centre, a core that was surrounded on either side by different layers of variable viscosity and hardness. Many of these live on, refined and sometimes relocated, in today’s optometrical terminology: the aqueous humour, retina, cornea, sclera, conjunctiva and so on. For the everyday medieval medic, though, ocular anatomy was thought less important than an understanding of how the four bodily humours were constituted within the eyes. A healthy eye was thought to be humorally cold and wet, and if swelling, irritation or bleeding occurred, cures sought to return it to this natural condition. Failing vision or infected eyes required treatment with pharma ceuticals of the appropriate humour, especially recipes that included earthy plants such as fennel, onion or garlic. Other more serious conditions were less well understood by medieval physicians and surgeons, who located them in various parts of the eye and attributed them to different causes. Cataracts, for instance, sometimes described as the unwanted gathering of cloudy vapours, were only considered curable in their early stages if at all, and a patient was normally prescribed herbal eye drops or minor surgery to the cornea with thin needles, which almost certainly did more harm than good.

Given the inevitably mixed success of such interventions, it was not uncommon for people to fall into blindness. In the Middle Ages this term did not necessarily imply a total lack of vision: without glasses or contact lenses many of us today might too have found ourselves in this medieval category. Some help was on hand. By the early 1300s readers in western Europe began to use Arabic-style reading aids, often in the form of polished ‘reading stones’ made of the mineral beryl, whose green lustre was thought particularly efficacious for good vision and whose curved lenses could magnify their texts. But for the more seriously poor-sighted or totally blind the only real recourse was to the charity of their immediate family or, for a lucky few, the religious arms of the state. The thirteenth-century poet Rutebeuf, writing satirically in Old French in around 1260, listed the blind among the regular denizens of Parisian street life:

Li rois a mis en i repaire,

Mais ne sais pas bien pour quoi faire

Trois cens aveugles route a route

Parmi Paris en vat trois paire

Toute jour ne finent de braire

‘Au iii cens qui ne voient goute.’

The King has set in one spot

Although why I know not,

Three hundred blind, road by road

Going though Paris in groups of three,

Everyday not ceasing to bray

‘Give to the Three Hundred who cannot see.’

These ‘Three Hundred’ were the eponymous residents of the Hôpital des Quinze-Vingts – literally the hospital of ‘fifteen twenties’ – a religious institution and charitable living-quarters recently founded to care for three hundred blind people by the French King, Philip Augustus. Making their way conspicuously through the streets in groups of three, sometimes led by sighted guides, the Quinze-Vingts would each day implore people to give alms to support their communal upkeep. Many, however, complained about their presence in the city and continued to view these blind beggars as something of an urban pest, ripe for victimisation. In 1425 an anonymous Parisian chronicler records an ‘entertainment’ in which four blind people were put in a park with a pig, handed clubs and told that if they killed the pig they could eat it. The crowd watched on, apparently in enjoyment, as the blind men nearly beat each other to death.

Such unpleasant harassment of the visually disabled, however, also co-existed alongside overwhelming praise for those who had the patience and faith to endure a lack of sight. The Mamluk Egyptian philologist and historian Khalil al-Safadi (c.1297–1363) dedicated two large treatises to the biographies of more than four hundred famous blind and one-eyed men who had overcome their disability to forge careers as great theologians, scholars, doctors or poets. In spiritual narratives, too, admiration of the blind’s achievements was even more profound. Christians, Jews and Muslims alike all framed a lack of sight as a trial of an individual’s morality. Those who suffered through such a test would be rewarded for their continued faith in the afterlife, and without the fruits of the human world to bother them they were also thought to be endowed with a potential to see deeper, more divine things. Uncluttered by earthly vision, they might instead learn to look with what the English mystic Margery Kempe (c.1373–1438) called the ‘syght of hir sowle’, an ability to glimpse with clarity the transcendent workings of God which lay behind all things.

Sniffing the Past

The exploits of the mysterious woman in the Cluny tapestries, then, are designed to prompt the viewer into both recollection and projection, mapping onto her five sensory games all sorts of ideas which lay behind the senses in the Middle Ages. Even today, when engaging with these pieces we cannot help but begin to imagine that we too are part of the picture, and this is intentional. Like many images of the medieval body, the tapestries deliberately encourage us to coexist with the depicted beholder. Seeing the young woman flashing a mirror to her unicorn companion, we are perhaps reminded of our own good luck in having eyes healthy enough to take in its vibrant scenes. We take her experience as our own and begin to sense what she senses.

At the same time it is, of course, impossible to actually reconstruct these medieval senses with any real precision. Sensory experiences are individual and subjective, making them extremely difficult things to describe or to share. Smell, for instance, is both particularly evocative and particularly personal. You and I, sniffing the same rose, even at exactly the same moment, cannot truly know for certain that our sensations match. And the words to which we might turn in comparing our experiences also fall short. There are various strategies. We might resort to the scientific or biological to elucidate: ‘That wine has a rusty, composty smell to it.’ We might borrow from other senses: ‘That cheese smells sharp and bright.’ Or we might rely on a shared set of undeniably abstract cultural concepts: ‘That perfume is so 1980s.’ But each type of sensory description is beset with a seemingly endless range of subtleties and specifics. In the mêlée of modern language we might talk of a whiff, a scent, a puff, a waft, a stink or a fragrance, all of which denote subtly different things in subtly different contexts, their meanings ever-shifting like the gusts of air on which they arrive and leave. This is the problem of what historians call sensory archaeology, the difficulty of bridging the millennium-long gap between an original medieval description of a sense and our own bodies in the here-andnow. We know that medieval thinkers theorised the action of smelling much like the action of sight, with scents travelling on the air to the nose and from there via the body’s animating spirit backwards to the brain for comprehension. But recapturing these past smells is inevitably an oblique act, sensed only through thick phenomenological clouds.

15. A gilded-copper censer or lamp from the mid-fourteenth century, made in northern Italy.

16. A brass and silver incense-burner made in Mamluk Syria, c.1280–1290.

Thankfully, objects can help with this olfactory conundrum. The two intricate metal items above were made only around eighty years apart on opposite sides of the medieval Mediterranean. Both are delicate pieces designed to contain burning incense and spices to perfume their surroundings. But they give access to two quite different cultural contexts for medieval smell.

The object on the left, the more ornate and larger of the two, was crafted in northern Italy, perhaps in the fourteenth-century Milanese workshop of the much sought-after sculptor and painter Giovannino de’ Grassi. It is a small but extremely detailed gilded-copper lamp, designed to diffuse both the glowing light and the sweet smells of the burning incense inside through six windowed openings. Men in biblical dress stand in front of these niches, with miniature angelic figures interspersed between them, both of which suggest that the piece was designed to be used in a Christian context. Smell was a fundamental part of medieval Church practice, and both the western Catholic and eastern Orthodox liturgy regularly called for incense to be burned in processions or to accompany particular moments of observance. Sweet smells themselves are frequently mentioned in biblical texts as key indicators of sanctity, and holy relics were almost always recorded as giving off a miraculous perfume, echoing Christ’s body, which, according to the Gospels, was anointed with scented oils after being taken down from the cross and prepared for entombment.

Smells were also used to dramatic effect in saintly vitae, with unexpected scents suddenly appearing in the hagiographic narrative to emphasise the theatrical turns of sanctity. In the life of the ninth-century Byzantine saint Irene of Chrysobalanton we read of the terrifying moment the saint is visited by a demon while praying in the room of her convent in Constantinople:

Then the demon stretched out his hand and kindled a stick against the lamp-wick. He dropped it around the neck of the holy woman, and it burned up as if fanned, violently inflaming her whole hood along with the scapular and the shift, and began even to lick her flesh. It went over her, scorching her shoulders, her breast, her spine, her kidneys and her flanks.

Smelling the fire, one of Irene’s fellow nuns soon traces her way to the source of the stench, where she finds a terrifying but wondrous sight: ‘Irene all in flames but standing immobile and unwavering and unconquered, paying no heed whatever to the fire.’ Promptly extinguished, the scorched Irene claimed to have felt little pain from the flames. And as her burns were treated, pulling away the fragments of garment now welded to her skin, the pungent, sickening smell of smoke and scalded flesh suddenly transformed into a gorgeous fragrance emanating from Irene’s holy wounds. Deliberately contrasting a suffocating reek with an angelic perfume, the vita relishes this luscious new saintly aroma, calling it ‘incomparably more fragrant than any perfume and precious scents, filling the whole convent for many days’.

In his lamp Giovannino de’ Grassi would have had similar sanctified smells in mind when he chose to surround its flame, emanating perfumed smoke, with religious figures. A jungle of gilded corkscrew vines, rolled leaves and opening flowers further evoke the abundant scents of nature, weaving their way around a micro-architectural structure that culminates in a series of pinnacled towers and battlements. Atop them all is an open spire, from which the whole ensemble would have hung or been swung by hand in procession from a short chain. These architectural flourishes were in part an allusion to the great churches and cathedrals in which such objects would have been used. But they also refer to the ultimate Christian city, Heavenly Jerusalem, the beautiful realm of the Eternal. More than just a sight to behold, heaven was also the olfactory seat of perfection, a lofty perfumed place full of saints, spirituality and, in the words of the fouth-century theologian Saint Augustine, ‘a fragrance which no breeze can disperse’.

The second incense-burner looks quite different from Giovannino’s. Made by an unknown craftsman in Mamluk Syria, a set of thin sharp tools would have been used to pierce patterns through its delicate brass and silver surface, allowing the smoking incense inside to waft through its small, sieve-like shell. Yet, like the Milanese lamp, its considered form also hints at the bigger ideas caught up with the medieval sense of smell. Christianity and Islam shared a conviction that the afterlife was a sweet-smelling place: the Qur’an calls Muslim paradise jannah ( ), a place most often evoked as an abundant, scented garden. At many moments life in the Middle Ages would have smelt rather pungent. While bathing seems to have been a more popular pastime than in the pre-modern centuries that followed it, people still tended to have only a few sets of clothes, which they washed and changed infrequently. The Garden of Paradise, by contrast, was completely unfettered by malodour, filled instead with gently flowing waterfalls, fruit that never rotted and rivers of honey and milk that always stayed fresh and fragrant. The houris (

), a place most often evoked as an abundant, scented garden. At many moments life in the Middle Ages would have smelt rather pungent. While bathing seems to have been a more popular pastime than in the pre-modern centuries that followed it, people still tended to have only a few sets of clothes, which they washed and changed infrequently. The Garden of Paradise, by contrast, was completely unfettered by malodour, filled instead with gently flowing waterfalls, fruit that never rotted and rivers of honey and milk that always stayed fresh and fragrant. The houris ( ), heavenly maidens who inhabited these gardens, were even said to be somehow formed of perfumed substances like saffron, musk, camphor and ambergris, precisely the sort of spices that would have been burned in the small Syrian lamp.

), heavenly maidens who inhabited these gardens, were even said to be somehow formed of perfumed substances like saffron, musk, camphor and ambergris, precisely the sort of spices that would have been burned in the small Syrian lamp.

The imagery that appears on this little sphere also affirms such heavenly pleasures. The lamp’s surfaces are decorated with seven cross-legged figures seated in seven roundels that represent the seven planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Earth and the Moon, at the time considered a planet in its own right. Above them, a central roundel is filled with the perforated rays of the sun, the whole scheme a reflection of the advanced state of contemporary Muslim astronomical science, which had for some time carefully studied the motions and meanings of these celestial bodies. The internal machinery of pieces like this were even more intricate than their surfaces. It contained a small bowl of lit incense set into a gimbal, a series of rotating rings which gyroscopically allowed their contents to remain upwards regardless of the position of its decorated metallic shell. This meant that the small ball could be rolled playfully back and forth without upsetting its contents. We might imagine it quietly zipping across a table, perhaps passed from guest to guest at dinner, or along the carpeted floor of a travelling tent with the incense’s sweet fragrance underscoring conversation.

Such smells, like their silver container, were a clear symbol of opulence and excess. The spices it was filled with – cloves, cumin, myrrh, jasmine, rose, camomile – were often pricey imports. But such scents were also valued for certain scientific properties that might have been particularly useful while eating or on the move through new lands. Disease was understood in the Middle Ages to be spread and received in part through polluted vapours or miasma. Good smells could counteract this bad air, cleansing as well as scenting their surroundings. Like its Christian counterpart, then, this burner was laden with multiple inferences, from heavenly symbolism to earthly expense, its miniature planets revolving like the heavens as it was passed around, swirling spices softly about the room.

All Ears

Teresa de Cartagena defined her deafness as separating her from the world. She was able to see the richness of things, to smell them, to touch them, but without her ears she still felt disconnected from people:

Ya soy apartada de las bozes humanas, pues mis orejas non las pueden oýr. Ya tiene silençio mi lengua plazera, pues por esta causa non puede fablar.

I am cut off from human voices, for my ears cannot hear them. My gossiping tongue is silenced, for because of my deafness it cannot speak.

She had lost her hearing young while growing up in fifteenth-century Burgos, in northern Spain, and later in life became one of the earliest women to write about her deafness in a short treatise named the Arboleda de los Enfermos, the ‘Grove of the Sick’. Ears in the Middle Ages were described as functioning through a narrow network of thin tubes that protected a small hair-lined well of stationary air that absorbed the resonance of incoming sounds. Following the familiar pattern of the body’s sensory organs, this sound was then conveyed to the brain by the spiritus for comprehension and judgement. For Teresa, lacking the ability to engage with this complex process was bittersweet: sad because it set her at a remove from many aspects of life, yet truly joyful because she felt living in silence opened her up to a series of sounds normally beyond human perception.

In his treatise De institutione musica (‘The Fundamentals of Music’), the sixth-century philosopher Boethius introduced an influential threefold classification of sounds that was to hold strong currency across the period and well into Teresa’s day. First there was musica instrumentalis, the sounds and songs of voice and instrument – string, wind, percussion – which people heard all the time in their normal earthly experience. Then there was musica humana, a more complex form of spiritual music. This was inaudible to men and women, but was constantly playing out as a series of resonant harmonies between the body and the soul. Even more refined was musica mundana, a phrase taken from the Latin mundus, the music of the world. These were sounds that set the medieval understanding of music into permanent dialogue with the study of philosophy and mathematics, the cosmic mellifluence of the spheres. Again, this world-music was beyond the audible grasp of mankind, but it was continuously resounding in the eternal movement of the planets and the changing of the seasons. It was almost theoretical sound: the underlying vibrations of God’s constantly humming universe. In Boethius’ paradigm, it was this trifold music that bound together song, man and the world, held in heavenly unison through polyphonic sympathy, and it was to the more sacred strains of this resonance that Theresa felt she was uniquely attuned. Deafness, like blindness, granted special access to the divine.

Given this conceptual, almost spiritual foundation for sound as at once audible and inaudible, it is unsurprising that the strongly religious culture of the Middle Ages felt able to locate a certain special sanctity in music. This was especially the case in sacred space. Synagogues, mosques and cathedrals, particularly those built at great expense on staggeringly large scales, were exceptional in comparison with most normal dwellings both architecturally, in their large size and vibrant decoration, and also acoustically, in their remarkable capacity for resonance. Average living-quarters would have mostly been uninsulated spaces whose thin timber walls would have left noises from adjacent rooms flat, dull and dampened. Religious architecture, on the other hand, often deliberately amplified and reverberated sound. Walking into the 184-foot-tall domed space of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople’s capacious fifth-century basilica church – later converted into a mosque under the Ottomans – a visitor would have encountered an otherworldly sonic space the likes of which they had probably never heard before, packed with echoing speech, the noise of footsteps bouncing repeatedly off the high walls and, of course, song. The German abbess and composer Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) went so far as to chastise officials who kept music separated from such spaces of spirituality. As she wrote in a letter to her archbishop: ‘Those who, without just cause, impose silence on a church … will lose their place among the chorus of angels.’ In addition to smelling good, Hildegard imagined that heaven had a profoundly holy, choral tenor to it. Whether filled with the well-established melodic lines of unaccompanied Christian plainchant or the Qur’anic verses intoned by imams before their congregation, these earthly spaces could have their vast expanses electrified through sound.

17. The interior of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, originally built as the Byzantine Empire’s first Christian cathedral by Justinian I in 537 and later converted into a mosque under the Ottoman sultan Mehmet II in 1453.

The loudest of these sacred sounds – in fact, probably some of the loudest man-made sounds a person was likely to encounter in the Middle Ages – were the chimes that regularly rang out from medieval belfries. Bells and their ringing were an important part of life, regulating the working day, and they were particularly important for Christianity from its very earliest origins. By the ninth and tenth centuries large cast-bronze bells became more and more common, carrying their sound for miles around and calling people to worship. These were complex objects and required a significant level of technological ability to successfully melt, shape and tune their metal. They were often cast on-site during a building’s construction, sometimes in sunken pits symbolically located at the very centre of a half-completed religious site, and from this auspicious birth an institution’s bell would continue to play a keen role in both promoting its faith and literally protecting its faithful. Loud, cacophonous sounds were thought to have an apotropaic effect, helping to drive away unwelcome spirits. As a result the names of saints were sometimes cast into a church bell’s rim, extending a sonic aura of goodwill and protection from the heavenly individual to anyone who heard its distant peal. One bell from the mid-1200s, donated to a church in the Italian town of Assisi by Pope Gregory IX, proudly proclaimed its multiple purposes in first-person poetic verses cast into its side, its efficacy intoned in repetitious lines like the slow chiming of the bell itself:

SABBATHA PANGO

FUNEREA PLANGO

FULGURA FRANGO

EXCITO LENTOS

DOMO CRUENTOS

DISSIPO VENTOS

I DETERMINE THE SABBATH

I LAMENT FUNERALS

I BREAK LIGHTNING

I ROUSE THE LAZY

I TAME THE CRUEL

I DISPERSE THE WINDS

Even without their resonating holy sound, bells were potent objects. If broken or cracked, they might be interred in holy ground like the dead. And they could be taken prisoner, used as political pawns in larger cultural clashes. In the year 997 the Muslim ruler of the southern Spanish caliphate of Córdoba raided and destroyed the major Christian pilgrimage centre of Santiago de Compostela. But instead of melting down the grand church’s bells for their valuable raw metal, they were held captive, hung as symbolic booty in Córdoba’s own Great Mosque.

The tunes and patterns to which these church bells were played was something their ringers would have learned by ear. Indeed, before the ninth century sacred and secular music alike would not have been recorded in writing but transmitted orally, committed to memory through experience and repetition. It was only in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that an increasingly complex system of notation began to develop that preserved these musical traditions more precisely. Work by the Troubadours, the composers of playful, lyrical love songs in southern France and northern Spain, began to be notated on pages packed with staved lines. And to standardise the emerging church practice of polyphonic prayer, enormous choir-books were transcribed at a size big enough for several clerics to gather around and sing. These earliest written melodies lacked the clearly specified speeds and dynamics of modern sheet music, but they at least conveyed intervals between consecutive notes and the relationship of tunes to their accompanying lyrics. Even so, memory was key, and much of this music’s nuance was still expected to be known in advance by the skilled singers and instrumentalists who performed it.

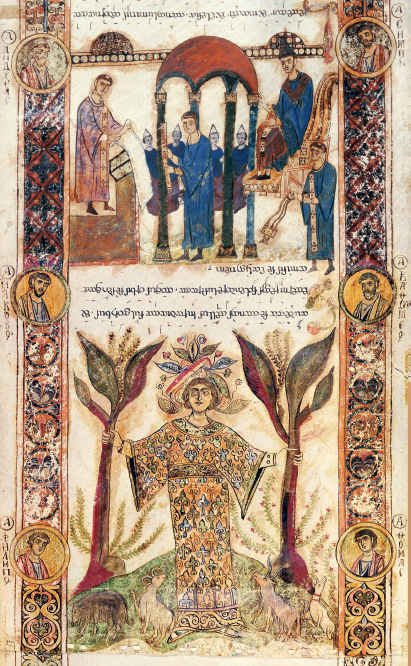

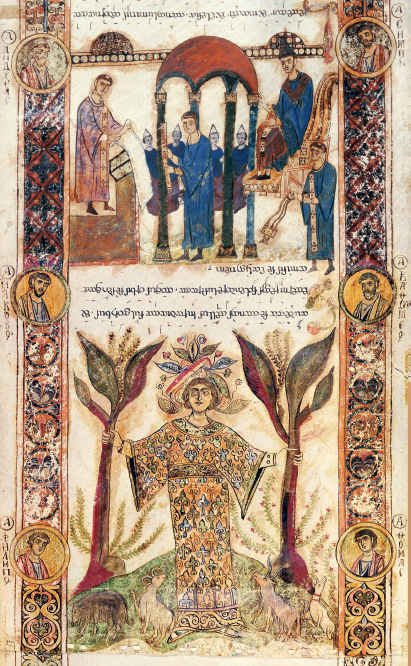

18. An Exultet roll from Bari in southern Italy made around the year 1000. Like all such rolls, this example combines images and text set upside down from each other, to be read by a priest facing in the opposite direction to his audience. In the upper image we see an Exultet roll being used in just this way.

This emerging style of musical notation has left a number of remarkable material remnants, from illustrated manuscripts of song decorated in bright, vivid colours to single stanzas of music etched onto the flat blades of carving knives, intended for singing at the dinner table. One group of Italian songs are particularly unusual in their format, not bound together on pages in the manner of a normal codex book but stitched into long continuous reams of parchment. Known as Exultet rolls, after the sung Easter prayers they contain, these long pieces of parchment – sometimes more than seven metres in total – juxtapose lines of Latin text, musical notation and rectangular images illustrating moralising scenes spoken of in the songs stretched across their width. The orientation of these scrolls seems topsy-turvy: the words and music face in one direction, the images completely in the other. But this was a deliberate flip. As the officiating priest sang the extended prayer from the roll’s text he would allow its end to flow forwards and over the edge of the pulpit on which he stood. While his song rang forth, the reversed images would slowly unfurl, appearing the correct way up for the observing congregation in front of him, giving continuously flowing visual form to the prayer as it unrolled for metres on end. Sound and image here combine to create an amazing multi-sensory performance, reliant on both the keen eyes and ears of the faithful.

Mouth, Tongue, Teeth

Like the eyes, the medieval mouth was considered a two-way street in sensory terms. Medical authors knew that in one direction it absorbed the raw information of taste before sending food onwards down the gullet to the stomach. And in the other, the mouth was outwardly communicative: it spoke, projecting sounds direct to the receptive coiling pathways of others’ ears. It can be hard to guess exactly how this medieval speech sounded. Its precise phonetic patterns have inevitably been lost in the intervening centuries, along with the native speakers of its many historic tongues. But by deconstructing written dialects of different languages from different regions, we can begin to piece together the contrasting cut of syllables, stresses of vowels and other sonorous nuances of their words.

Speakers from some places, we intuit, would have sounded soft and sweetly tongued, others much more precise and guttural in their tone. Medieval sources themselves commonly comment on vocal differences from country to country, setting the pleasant subtleties of certain accents against the incomprehensibility of others. Germans said that eastern languages sounded mangled and harsh. Egyptians thought it was easy to identify non-native Arabic speakers by their flat, European tone of voice. And the pace of language was apparently just as noteworthy. The journal of the Franciscan missionary William of Rubruck, who in the thirteenth century travelled thousands of miles from his native Flanders to Karakorum, the capital of the Mongol Empire, recorded with surprise that the priests of the ‘Saracens’ – a somewhat derogatory catch-all for Muslim Arab peoples – sat ‘all mute in manner’ and he could not ‘provoke them unto speech by any means possible’. In comparison, some European dialects were criticised by contemporaries for their strange and busy noisiness. The historian Ranulph Higden (c.1285–1364) tried in his writings to explain the confusing tripartite heritage of medieval England’s many divergent accents, but even he had to conclude that the language was a corrupted and somewhat ugly one:

Englisch men, they hadde from the begynnynge thre manere speche, northerne, sowtherne, and middel speche in the myddel of the lond, as they come of thre manere peple of Germania, notheles, by commyxtioun and mellynge firste with Danes and afterward with Normans, in meny the contray longage is apayred, and som useth straunge wlafferynge, chyterynge, harrynge and garrynge, grisbayting.

English men, they have from the beginning three manners of speech – northern, southern and middle speech in the middle of the land – as they come from three manners of people from Germany [the Jutes, the Angles and the Saxons]. Nonetheless, by intermingling and mixing, first with the Danes and afterwards with the Normans, in many the country’s language is damaged, and some use strange babbling, chattering, snarling, clicking and grinding of teeth.

Other peoples were praised for the unusually high quality and texture of their speech. Early Muslim travellers, journeying deep into the Arabian desert in the eighth century, came across remote Bedouin communities whose quality of Arabic they described as amazingly uncorrupted, untainted by city life and held up as a purer, more poetic form of the language.

Individual speakers were also admired for their silver tongues and beguiling rhetorical mastery, especially influential teachers and preachers – Muslim, Jewish and Christian alike – who acted as the professional mouthpieces of God. Saint Anthony of Padua (1190–1231) was one such revered speaker, his oratory praised for its clever constructions and musical rhythms as they fell upon the ear. One contemporary biographer claimed that, when Anthony addressed a crowd of pilgrims in Rome who had gathered from different points across the globe, the saint’s speech was so glorious that each member of his multi-ethnic audience miraculously heard his emotional preaching in their own mother tongue. A short time after his death Anthony’s holy jawbone, seen as the anatomical foundation of his impressive oratory, was preserved as a relic, its elaborate precious metal reliquary posthumously reconstructing a head and shoulders of gold and silver around the saintly mandible that had once spoken so mesmerisingly. Many pilgrims seeking spiritual countenance flocked to see the remains on display in Padua Cathedral, and they were certainly impressive to behold. The reliquary, embellished many times over the centuries, includes an enamel base mounted on three seated miniature lions, a gilded halo interspersed with angelic figures, and a sparkling tiara and necklace studded with pearls, jewels and glass cabochons. At its face, the relic itself was mounted within a domed piece of clear rock crystal so as to make it as visible as possible to onlookers.

19. Reliquary of the jawbone of Saint Anthony of Padua, made in 1349 and embellished with many later additions being processed around the city’s streets.

But the interaction of medieval congregations with objects like this often went well beyond mere looking. Visiting a saint’s shrine could be a distinctly oral experience too. Touching and, especially, kissing holy remains were thought to give even more direct access to the divine than simply appearing before them, and following this osculatory logic all sorts of objects became targets for pilgrims’ puckered lips. Byzantine icons had their painted surfaces worn away by over-zealous kisses, exposing their subcutaneous wooden structures. Muslim and Jewish shrines were described by contemporaries as sporting large tomb slabs set into their floors, ideal for kneeling down and kissing. And surviving manuscripts of most religious persuasions exhibit similar signs of wear, their likenesses of holy figures or the ornamented text of holy names now smudged and watermarked, sometimes even completely destroyed by repeated kissing of the parchment. The mouth was a key point of contact for the sacred to flow back and forth.

Unlike the lips, the tasting tongue was less a place to signal the passion of religious experience than an organ through which to read the imminent onset of illness. Like all of the senses, one’s taste could be knocked off-balance by humoral misalignment, indicated perhaps by a constant bitterness, inflamed tongue pores or a suspicious discoloration to its underside. Medical authorities recommended seeing to such maladies by rubbing the tongue with small packages of spices, including iris stems and aniseed. Even when healthy, the tongue could be used as a conduit for healing the rest of the body. For cases of witlessness or muteness one ninth-century English manuscript advises that medicines should be taken into the patient’s mouth and the sign of the cross made under the tongue before swallowing. And if such prescriptions called for particularly bitter or pungent spices, it was no matter: they could always be followed with one of the prominent remedies recommended in later medical compendia for curing bad breath, including drinking perfumed wine or keeping a laurel leaf under the tongue. Were a patient wealthy enough, they might even swallow small pieces of gold and ground jewels, transmitting material expense into medical efficacy on the tongue.

20. A dentist holding a string of teeth, removing the tooth of a patient with a pair of pliers. The image illustrates an entry on dentistry in the Omne Bonum, an encyclopedia written by the English author James le Palmer in London around 1360–1375.

As well as the evidence of these cleansing gargles, archaeological remains from the Middle Ages suggest that levels of oral hygiene were significantly better than we would expect from the stereotype of a blackened medieval mouth, although differing diets meant standards would have varied significantly from place to place and between social classes. With greater amounts of expensive imported sugar in their food, the wealthy might have been prone to problems caused by an excessively sweet diet, whereas it was the coarseness of the cheap flour in a peasant’s loaf of bread that would have caused them longer-term tooth trouble. Dental advice was of some concern for university-trained physicians, but more often it fell to the practically minded surgeons and barber-surgeons or specialised dentists found in most large medieval towns. Providing that one visited a practitioner who had received a sensible training – as opposed to a masquerading charlatan or quack doctor – these healers were likely to offer at least some sound advice. Those with sensitive teeth were told to avoid eating hot and cold food in close succession, and that washing the mouth with appropriate concoctions could help ailing gums. In extreme cases, though, difficult teeth had to be removed and the cavity treated with herbs and spices, especially peppercorns, which were thought particularly efficacious for the mouth. In removing a painful tooth, authoritative texts stretching back as far as antiquity claimed that the goal was to expose and extract the ‘tooth worm’, a tiny creature that they held to be responsible for dental pain. But by the early modern period it was generally agreed that what remained after tooth removal was in fact a stub-like nerve which, devoid of its covering, could sometimes take on a surprisingly worm-like appearance.

A healthy, beaming smile seems not to have been a particularly pivotal aspect of beauty across Europe and the Middle East in the Middle Ages, certainly not as important as it is today, and it is rare to find smiling figures at all in medieval images. Still, the quality of medieval orthodontics meant that, for those who could afford it, removed teeth could be easily replaced to ensure a tooth-filled grin. The surgical author Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936–1013), a prolific and influential writer working in Muslim Spain and well known in the Latin-speaking world by the name Albucasis, offered complex procedures for replacing extracted teeth with prosthetic originals. These were often formed of carved animal bone and tied in place next to their neighbours with thin gold thread. What happened to the original teeth thereafter seems to have been the dentist’s business. An illustration from an encyclopedia assembled by the English author James le Palmer in the mid-fourteenth century shows a dentist at work, bending over the patient with grim concentration and a pair of black pliers, originally painted silver but now tarnished by time. Around his shoulder he seems to clutch a necklace from which hangs a series of enormous exaggerated teeth: at least someone benefited from the nefarious workings of the tooth worm.

21. The sixth and final Cluny tapestry, showing the young woman and her beasts in front of a tent featuring the mysterious phrase: A MON SEUL DESIR. Its meaning is yet to be fully deciphered.

We can only hope for her sake that the woman in the Cluny tapestries who feeds sweet, tooth-rotting berries to her parrot and monkey did not try too many herself. Repeated overindulgence would have been a swift road to visiting a dentist like James le Palmer’s, perhaps even one similarly dressed in the rich bounty of the mouth. Still, this was just the sort of connection that the Cluny tapestries were designed to encourage in their medieval viewers, bouncing back and forth between the young woman’s sensory experiences and their own. The five pieces in effect define and individuate the five different ways in which a single body might perceive information from the world around them through the senses. But at the same time, in having the same set of recurring characters play out the full quintet of human sensations in turn, the tapestries also serve to bring human sensory experience together. These were, after all, objects to be seen not one by one in isolation but as a unified group, enveloping the viewer around the wide walls of a single room. United as a set, they layer the senses one atop the other just as they were layered in everyday medieval life. The sixth and largest of the Cluny tapestries gestures towards just this sort of sensory unison. It remains the most mysterious of the series. The young woman is again centre stage atop her floating island full of trees and plants, this time standing before a tent, in the middle of taking – or perhaps replacing – a golden necklace from a box held by her faithful maid. Across the top of the tent’s entrance an ambiguous motto is emblazoned: A MON SEUL DESIR, ‘to my sole desire’. What this desire was remains only for her to know. But surrounded by beasts drawn from her previous five scenes – the monkey, dogs, rabbits, birds and, of course, her lion and her unicorn – we can presume that, whatever this ultimate pleasure may have been, it was only to be truly reached and enjoyed to the full through the combined perception of the body’s five senses.

commonly called ‘The Book of Scientific Knowledge’). ‘The eye is like a mirror’, he argued, ‘and the visible object is like the thing reflected in the mirror’. The second, competing idea of vision also developed from classical writings, especially the Greek theoretician Euclid and the Roman writer Ptolemy, but conceived of sight as functioning the other way round. It was not objects that projected light, they argued, but the eye itself that expressed rays outwards until they alighted upon an object. Sight in this mode was an almost tactile process, with invisible emissions from the eyes feeling their way through space to illuminate the world with their diaphanous touch.

commonly called ‘The Book of Scientific Knowledge’). ‘The eye is like a mirror’, he argued, ‘and the visible object is like the thing reflected in the mirror’. The second, competing idea of vision also developed from classical writings, especially the Greek theoretician Euclid and the Roman writer Ptolemy, but conceived of sight as functioning the other way round. It was not objects that projected light, they argued, but the eye itself that expressed rays outwards until they alighted upon an object. Sight in this mode was an almost tactile process, with invisible emissions from the eyes feeling their way through space to illuminate the world with their diaphanous touch.

),

),  ), heavenly maidens who inhabited these gardens, were even said to be somehow formed of perfumed substances like saffron, musk, camphor and ambergris, precisely the sort of spices that would have been burned in the small Syrian lamp.

), heavenly maidens who inhabited these gardens, were even said to be somehow formed of perfumed substances like saffron, musk, camphor and ambergris, precisely the sort of spices that would have been burned in the small Syrian lamp.