It was known long before the Middle Ages that bones formed the body’s foundation, a structural framework around which everything from muscles and nerves to veins and flesh was wrapped. Early medieval authors described most sections of the skeleton relatively thoroughly in their treatises, individuating the bones and their different functions: the ribs fortified the chest, the skull protected the soft brain beneath, the clavicle – from the Latin clavicula, meaning ‘little key’ – locked the arms to the chest at the shoulder. Still, there was not always certainty as to the tally of bones the body contained. A few writers stumped for a total of 229, while some maintained that males had 228 bones, two more than females, who had 226. Others thought specifically that men had one rib fewer than women, a single bone missing in an echo of Genesis, which told of God creating Eve from Adam’s side.

The confusion was the result of a practical problem. To see bones as a clean, white and easy-to-count skeleton first required the removal of the tough tendons and ligaments that bind the muscles to them. This was, and still is, a time-consuming business. Limbs and other body parts have to be carefully boiled to loosen the fibres of these fleshy elements and encourage the core to slip out like a freed lamb bone from a stewed shank. In the medieval period, opening up the body was fraught enough without brewing up such controversial casseroles. Besides, getting to the bones by boiling also had the obvious drawback of destroying most of the cadaver in the process, rendering the corpse unacceptably despoiled and, ultimately, unobservable. It was only later, in the early modern period, that the construction of anatomical teaching skeletons rose to prominence, and even then the bones of a dissected corpse tended to have its flesh not boiled but slicked away, using aggressive corrosives such as quicklime.

Bones, then, were somewhat frustrating things, clearly important but unattainable and interior beneath the skin. This also had the effect of limiting their appearance in medical images of the time. When they do feature, they feel familiar but slightly skew-whiff. The skull is there, but with only some of the jagged suture lines that run outwards from its centre. The squared-off jawbone is sometimes shown correctly as an independent piece, but more often is fused with the cranium to form one strange giant bone-head. The pelvis, too, has a tendency to be shown warped and curvy, as if combined with the sacrum into a single semicircular unit. And piano-key spines extend from the neck to the coccyx with the ribs flourishing outwards, but often without individual vertebrae, appearing just as a single wobbly line running down the back. Sometimes an effort is made to echo the interiority of the skeleton, so hard to see in reality, by displaying the bones as an interconnected framework sitting verifiably within the body. Layers of painted muscle and flesh are built up around the skeleton in recessing bands of deep marbled purple and lighter red. But more often depictions dispense with any sense of realism altogether.

An image from 1488 copied alongside the writing of the Persian author Mansur ibn Ilyas (c.1380–1422) shows just such a schematic view of the bones. The figure is strangely warped, with a flat, seemingly reversed, heart-shaped head, in which the eyes and nose face upwards towards the top of the page. Those in search of an ignorant Middle Ages might quickly write this off as an error, the work of an illustrator who had no idea what a skeleton really looked like. Yet if we look a little more closely, we realise that this is in fact a dorsal view. Like its western counterparts, this image pictured the skeleton from behind: the elbows and the palms face the viewer, laid on their front, and the head is tipped backwards at an extreme angle so that the upper vertebrae of the spine can be seen in their entirety. The interest for those reading Mansur was clearly not in seeing a skeleton presented with perfect accuracy. After all, any healer experienced enough to be reading a dense and theoretical book like this would be more than familiar with the detail of real human bodies. Rather, what they wanted from such an image was a different kind of knowledge. Littered around the stylised outlines of the bones are tiny sections of explanatory text, listing their names and differentiating their functions. This is the skeleton as a presentation device, designed to make the detail of the bones more memorable. It conveyed terminology, an intellectual framework for medical understanding, built up around the body’s bones.

33. A diagrammatic skeleton explaining the detail of the bones in the body, from a copy of the Tashrih-i badan-i insan ( , ‘The Anatomy of the Human Body’), by the Persian author Mansur ibn Ilyas, completed in December 1488.

, ‘The Anatomy of the Human Body’), by the Persian author Mansur ibn Ilyas, completed in December 1488.

More practical medicine took a different approach to the bones. Medieval osteological health had a well-established repertoire, particularly the work of surgeons who could offer practical expertise in the case of bruises and breaks. Dislocations and their healing – what the influential Italian surgeon Teodorico Borgognoni (c.1205–1298) referred to as ‘the joining of the disjointed’ – were thought to be best addressed by the firm manipulation of the affected limb under traction, with stretching force applied to the area, either by hand or using a number of innovative devices. For hip dislocations the lower legs would be bound together at the shins and a small animal-skin bag inflated between the thighs, popping pelvic joints back into place. For the spine, elaborate wooden racks would be used in conjunction with the surgeon’s body weight to palpate or stretch the patient. Such stretching alone would probably have provided little long-term help but may well have lessened the pressure on crushed nerves and reduced the spasming of over-extended muscles, giving the patient some genuine relief.

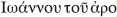

Even more successful was the resetting of fractured or fully broken bones using braces and tight bandaging to immobilise and realign limbs, followed by the application of various salves and medicaments to help the bones heal. We get a good sense of these methods in an assorted book of medical, religious and magical texts written in Greek around the year 1440 by a little-known practitioner named John of Aron ( ). The parchment of the manuscript has not survived particularly well, scuffed and stained across its surface, perhaps suggesting frequent consultation. Nevertheless, one of the pages still clearly shows a series of nine faces diagrammed side by side, each wrapped in different snaking webs of brown bandage. Their different configurations are designed to secure a range of damaged bones, each named by shape and style:

). The parchment of the manuscript has not survived particularly well, scuffed and stained across its surface, perhaps suggesting frequent consultation. Nevertheless, one of the pages still clearly shows a series of nine faces diagrammed side by side, each wrapped in different snaking webs of brown bandage. Their different configurations are designed to secure a range of damaged bones, each named by shape and style:  (‘around the head like a helmet’),

(‘around the head like a helmet’),  (‘entangled, around the face’),

(‘entangled, around the face’),  (‘rhombus-shaped’). Another illustration from the same book shows a more elaborate bone-setting scene in action. The patient is stretched out face down on a traction machine, while two assistants tighten the rack at either side. The whole affair seems rather grand, taking place beneath an ornate canopied archway, its hanging lamps and patterned dome invoking the mosaic decoration of a luxurious bathhouse. It must be warm, for the assistants are naked and the attendant physician wears only a towel around his waist as he manipulates the patient’s back with a plank.

(‘rhombus-shaped’). Another illustration from the same book shows a more elaborate bone-setting scene in action. The patient is stretched out face down on a traction machine, while two assistants tighten the rack at either side. The whole affair seems rather grand, taking place beneath an ornate canopied archway, its hanging lamps and patterned dome invoking the mosaic decoration of a luxurious bathhouse. It must be warm, for the assistants are naked and the attendant physician wears only a towel around his waist as he manipulates the patient’s back with a plank.

34. Two pages from different parts of a medical book written in Greek around 1440 by the healer John of Aron. On the left are different positions of bandaging on the face, and on the right is the torsion of the body to relieve pressure on the joints.

Healing techniques like this were not restricted to human bones. The fourteenth-century veterinarian Abu Bakr al-Baytar, a specialist working in the royal court of Mamluk Egypt, developed detailed processes for the construction of large-scale splints that could be administered to horses or cattle with broken bones, as well as ingredients for curative remedies and painkillers to be given in far stronger doses than to men and women. Animal medicine like this was not often recorded. Farmers, almost all of whom would have been unable to read and write, had little need to document in long-winded detail the husbandry that they had already been practising for generations, passed on by observation and oral tradition. Instead, such veterinary writings were normally the preserve of the keepers of high-end beasts like alBaytar. Healthy stable and working animals were of vital importance to the smooth running of various matters of state, from processions and festivities to diplomatic travel and war. Instructions for complex surgeries on animals were therefore valuable things, laden with intriguing details that tell of surgical incisions for accessing the bone, as well as injections of immobilising substances to stop animals struggling and techniques for cauterising openings after surgery. Other books list recipes for extremely viscous pastes that could be used to still, stiffen and protect more subtle fractures, even in the difficult case of a broken wing sometimes sustained by the large, hawks used by the aristocratic elites for hunting. Given the immense popularity of the sport in wealthy circles across the Mediterranean, knowledge of how to heal the bones of birds could be just as important, and just as lucrative, as operations on human patients.

35. A bowl probably made in twelfth-century Iran by a Seljuk ceramicist, showing a prince hunting on horseback with birds. Such creatures were just the type of high-status animals that the Mamluk veterinarian Abu Bakr al-Baytar would have treated.

Set diametrically against these more hopeful concerns of healers, who thought they could tend to and revive the living skeletons of both man and beast, was the near-constant presence of the bones in medieval cultures of death. This was their most blunt and by far their most prominent role in the Middle Ages, a marker of people’s intimate and public relationship to the realities of living and dying. Where the bones finally came to rest could be extremely important, a site of sadness, joy, memory and spiritual exchange between the dead and the living.

For most in the period, designating where one wished to be buried was something undertaken while still alive, sometimes long before reaching old age or sickness. Honouring such wishes was thought particularly crucial. We can see this most easily in the cases of several high-status individuals. Given their extreme wealth and their ability to travel, it was not uncommon for a king or queen, sultan or emperor, to die some distance from the pivotal political centre of their realm. And as their bodies could hold substantial dynastic currency for both their followers and their nation, a royal’s successor could find themselves with the difficult job of transporting posthumous remains some distance to a place appropriate for a sufficiently momentous burial. Moving corpses across continents, though, was not easy. After the death of the Carolingian King Charles the Bald in the Alpine town of Avrieux in 877, his body was gutted and stuffed with aromatic preservatives, salt and wine to facilitate its intact return to the Cathedral of St Denis, some 600 kilometres away on the outskirts of Paris. Alas, so strong was the body’s nauseating stench that the King’s party could only take him as far as nearby Nantua. It was only seven years later that what remained of his body was disinterred and returned to the capital by a particularly devout and adventurous monk. While such removal was streamlined somewhat over the centuries, it still remained a momentous undertaking. When King Louis VIII died in the Auvergne in 1266, his followers were presented with a journey of similar complexity and distance. This time the corpse was salted, wrapped in waxed cloth and sealed into a stitched-up cowhide to save the noses of those who bore his bones.

This dedication to the place of death was particularly integral to all three of the predominant faiths of the Middle Ages. In religious terms death was seen not as a finite end, but rather as an important crossing point into another realm, from one earthly stage of life to another less tangible one. This was most discussed in Christianity. Earlier Greco-Roman practice from which the religion stemmed tended to emphasise individual biographies of the deceased through familial ancestries: men and women might have died, but their links to kin and clan remained. The New Testament reframed this as more of a spiritual persistence. The powerful animating soul, medieval theologians agreed, lived only temporarily within the body, and while death marked the cessation of a person’s perishable earthly form, this was but a single moment in the soul’s longer journey. This continuity would only end upon its very final reckoning at the moment of an imminent and apocalyptic Last Judgement. There were two exceptions. If in life you had committed an unforgivable level of mortal sin, your soul would be condemned immediately to hell on departure from the body. Likewise, if you had been astoundingly saintly, through good deeds or holy martyrdom, your soul would leave the dead body to rise directly to heaven. For most normal folk, however, death marked the soul’s shift into a rather more complicated state of limbo, awaiting its ultimate sentencing until the End of Days, whenever that might be.

36. Sculpted scenes above the western door of the Cathedral of Conques in southern central France, finished around 1107. It offered a powerful vision of the Last Judgement for the faithful to see every time they entered the church, with a large central image of Christ judging the good on his right-hand side and the bad on his left.

It was only after the influential writings of thirteenth-century theologians such as Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) that this concept of purgatory was fully fleshed out by the medieval Church, and their ideas made clear that earthly bones could have a serious impact on this intermittent realm. While alive, living the life of a good Christian would begin a favourable process of judgement. Living well, spiritually speaking, involved not only faithful prayer and Christian good deeds but also engaging materially in churchly pursuits, pilgrimage, crusade or the patronage of sacred objects and spaces. But, once dead, the continued well-being of your eternal soul was entrusted entirely into the hands of the living. Each time they invoked your name in prayer, your purgatorial sentence was shortened and alleviated. Some wealthy individuals sought to amplify this spiritual support by striking deals for posthumous remembrance. They founded and funded whole religious institutions – monasteries, convents, abbeys, cathedrals – writing into their charters that an entire foundation’s religious inhabitants would, in exchange, pray for their munificent benefactor daily for generations to come. In particular, the existence of miraculous relics had long proven a lingering connection between the body and the soul, even after its departure, and thus this alleviating power of prayer was thought all the more potent at the graveside. For both rich and poor the site of bones acted as a sort of bodily antenna for sending spiritual countenance to the abstracted soul.

Unlike this rather detailed account in Christian scripture, discussions of the appropriate way to treat a body and its burial place after death are not much mentioned in the Qur’an. Medieval Islamic thinkers were forced to build up their own recommendations in a series of advisory manuals on the burial of bones. Especially popular was the tenth-century Afghani author Husayn al-Baghawi’s Masabih al-Sunna ( roughly translating as ‘The Lamps of Prophetic Teaching’), which included, among other details, the commonly held Muslim belief that burial should follow quickly after death, preferably within a day, a practice still upheld. For Islam’s early communities this would have been an important practical measure. A dead body would not stay untroubled for long in the intense desert heat of the Arabian Peninsula or other temperate Islamic lands and so was placed quickly into a grave, dressed only in a simple shroud and leant on its right-hand side so as to orient it towards the qibla (

roughly translating as ‘The Lamps of Prophetic Teaching’), which included, among other details, the commonly held Muslim belief that burial should follow quickly after death, preferably within a day, a practice still upheld. For Islam’s early communities this would have been an important practical measure. A dead body would not stay untroubled for long in the intense desert heat of the Arabian Peninsula or other temperate Islamic lands and so was placed quickly into a grave, dressed only in a simple shroud and leant on its right-hand side so as to orient it towards the qibla ( ), the sacred direction of Mecca. But there was also a spiritual haste. A person’s soul was thought to depart the body with speed upon death, creating a metaphysical divide between material and spiritual worlds that was to be resolved only when the soul was reunited with an idealised version of the body after the Day of Judgement, or Qiyamat (

), the sacred direction of Mecca. But there was also a spiritual haste. A person’s soul was thought to depart the body with speed upon death, creating a metaphysical divide between material and spiritual worlds that was to be resolved only when the soul was reunited with an idealised version of the body after the Day of Judgement, or Qiyamat ( ). Archaeological evidence suggests that such burial traditions were being followed by Muslim populations across the Middle East and even as far west as Nîmes in the south of France, where Islamic Umayyad communities briefly settled in the early eighth century after their armies advanced northwards over the Pyrenees from Muslim Spain. Here, bodies were discovered correctly dressed and oriented, with their hands laid so as to cover their face, a poignant gesture of the bones in perpetual holy deference and grace.

). Archaeological evidence suggests that such burial traditions were being followed by Muslim populations across the Middle East and even as far west as Nîmes in the south of France, where Islamic Umayyad communities briefly settled in the early eighth century after their armies advanced northwards over the Pyrenees from Muslim Spain. Here, bodies were discovered correctly dressed and oriented, with their hands laid so as to cover their face, a poignant gesture of the bones in perpetual holy deference and grace.

The final resting places of medieval Jews can be even more complex to uncover and interpret. Jewish communities lived as minorities across the entirety of the Middle Ages, their lives exclusively taking place under the rule of other faiths. Following the advice of the Old Testament book of Proverbs that ‘the rich and poor meet together in death’ – a reminder that material goods are of use only to the living – they often left little in the way of ostentatious or symbol-laden tombs and grave-markers over the bones. This material sparsity is further compounded by the extensive periods of persecution Jews underwent across Europe at various points in the period. Ostracised from Visigothic Spain in the seventh century, massacred in Germany in the eleventh as an offshoot of the First Crusade, expelled from England altogether in a royal edict of 1290, to name just the more major instances, Jews rarely had the political freedom to bury their dead in the manner they wished. And even when they did, medieval Hebrew texts outlining funerary customs tended to focus on instructions for mourners. They called for a certain juxtaposition, counselling expressive grief in private but deliberately internalised, restrained quiet in public: tearing one’s clothes and garments at the bedside of the deceased, but heralding a death to the world only by hanging a small cloth outside the house and opening all of its windows. Attitudes to the corpse itself were similarly contrasting, at once an object of extreme deference and potential pollution. Touching dead bodies directly was considered irreverent – something especially to be avoided by the kohanim ( ), the priestly class – apart from when ritually washing the deceased for burial, anointing them and enshrouding them in linen sheets and clothes. Once wrapped, the body would be taken to the nearest cemetery that permitted Jews, often a significant distance outside of urban centres, and interred in a coffin or on short wooden planks. The grave was normally marked only by a simple stone slab with the name of the person buried beneath, but preserving the body in good corporeal order like this would have kept in line with Jewish teachings of a conceptual, mystical messianic time known as ha’olam ha’ba (

), the priestly class – apart from when ritually washing the deceased for burial, anointing them and enshrouding them in linen sheets and clothes. Once wrapped, the body would be taken to the nearest cemetery that permitted Jews, often a significant distance outside of urban centres, and interred in a coffin or on short wooden planks. The grave was normally marked only by a simple stone slab with the name of the person buried beneath, but preserving the body in good corporeal order like this would have kept in line with Jewish teachings of a conceptual, mystical messianic time known as ha’olam ha’ba ( ), ‘The World To Come’. At this future moment the dead would rise from their graves for a redemptive return to the Land of Israel, the bones reanimated for an eternity in an age of paradise.

), ‘The World To Come’. At this future moment the dead would rise from their graves for a redemptive return to the Land of Israel, the bones reanimated for an eternity in an age of paradise.

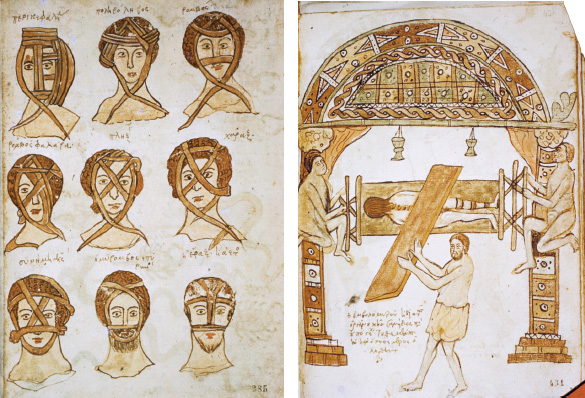

In practice, these three religious frameworks for death and burial varied dramatically between different communities and across the centuries. And there were also many points of exchange between them. Jews passed to Christians the tradition of anointing the corpse, Christian kings could be buried in shrouds of expensive cloth woven by Islamic textile-workers, and Muslim cemeteries could stand side by side with Jewish graveyards at a city’s limits. Rather than something to shy away from, this cross-pollination could be proudly worn as a sign of medieval multicultural sensibilities. In twelfth-century Sicily, a kingdom where the faiths enjoyed comparatively cordial relations, language at the graveside reflected the shifting sands of these religious worlds. A large stone slab discovered in Palermo at the church of San Michele Archangelo records the death of a woman named Anna. It is most likely the end of a sarcophagus commissioned for her by her son Grisanto, a Christian cleric of Sicily’s Norman king. Split into four distinct quarters, arranged around a simple circular mosaic, each bears a section of text that mourns Anna’s passing respectively in a different tongue: Greek, Latin, Arabic and Judeo-Arabic, Arabic words written in Hebrew letters. Calling out in a polyglot chorus from her grave, they prompt the visitor to memorialise Anna’s life and invoke good wishes in her name, all speaking versions of the same refrain, ‘Here lies Anna, mother of Grisanto, buried in this Church in the year 1148’:

37. A quadralingual gravestone made in 1149 to commemorate a woman named Anna who had died the previous year. Prayers to the deceased are written in Latin, Greek, Arabic and Judeo-Arabic.

If these funerary customs and linguistic memorials directed the voices and actions of the bereaved at the site of the grave, what of the dead themselves? Could they be reanimated? How was their presence felt beyond putrefying flesh and emerging bone in the ground below? Medieval craftsmen offered a powerful response to these questions by creating tombs and grave monuments designed to extend an individual's presence long after their mortal demise.

Given that graves were sites for transactional mourning, where the pious actions of visitors could directly affect the quality of the deceased’s eternal salvation, a certain spatial politics began to play out in the placement and embellishing of these sites of death. In small villages and larger cities alike, most people would have been interred in communal burial space within cemeteries dedicated to their respective faith. There were unfortunate exceptions. The poorest might struggle to meet the cost of interment in sacred ground, their burial falling instead to the charity of others, who would, in turn, receive serious spiritual recompense for taking on a pauper’s debt. And those who were thought to have died from particularly contagious sicknesses – plague, for instance, or sometimes leprosy – would normally be removed from the bulk of the population and end up in mass graves mostly outside city walls. At the other end of the social scale, at least in Christian societies, more aspirational citizens like nouveaux riches merchants, local aristocrats or high-ranking clergy could fund particularly prestigious burial inside a church, jostling for the choicest spots in proximity to the sacred space of the high altar. They were, in effect, peacocking for the all-important purgatorial prayers. Indeed, those at the very highest levels of society might side-step such concerns altogether: they commissioned additional wings to buildings or endowed entirely new foundations where their family’s dead might be repeatedly interred. Such elaborated spaces effectively became dynastic necropolises, a corporeal red carpet displaying a family’s unbroken lineage and justifying the continued and undeterred reign of their living relatives. Such substantial monuments – the sculpted tombs of the English royalty in Westminster Abbey, say, or the domed mausolea of Mamluk sultans in Cairo – would have been monumental projects, sustaining the political clout of ancestral bodies well into the future.

As well as prominent placement, the status of the medieval deceased was also conveyed in the material abundance of their tombs. The wealthy in life remained wealthy in death. Gilded metals, jewels or beautifully patterned stones all elevated the body’s immediate surroundings, redirecting onlookers to think more about the glittering legacy of the deceased than their body interred within, slowly turning to dust. Some relied on sheer staggering presence. The princes of various Persian dynasties deliberately ignored contemporary Islamic prohibitions against ostentatious funerary structures by erecting extremely tall and pointy brick mausolea. One such structure still stands in the ruins of the Persian city of Jorjan, now in northern Iran, a towering 53-metre-high turret built in the year 1006 for a Ziyarid emir named Qabus ibn Wushmgir, whose name is commemorated in circular kufic inscriptions that wrap around its circumference. Others turned to intricacy and more emotive imagery to move the viewer. The fifteenth-century French dukes of Burgundy, Philip the Bold and John the Fearless, found final resting places in a pair of elaborate personal monuments whose central sculpted tombs were each supported by a throng of miniature alabaster mourners. Each of these tiny figures is dramatically hooded and strikes a different sensitive pose, frozen in multiple actions of grief that might have been experienced by those beside the grave. Perhaps the most materially minded of all were the emperors of Byzantium, who for nearly seven hundred years followed the example of Constantine the Great and chose to be entombed in large marble sarcophagi within the ancestral necropolis of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. These rulers do not seem to have been particularly interested in complex carvings or affecting decoration. They focused instead on the multitude of different properties to be found in one particular stone’s coloured seams. Their sarcophagi were hulking, impossibly heavy caskets, carved from marbles of all possible hues and shades: rich green Thessalian marble, rosy and speckled Sagarian marble, colourful Hierapolitan and Proconesian stones and, most prominently, a rich purple porphyry. So strong was the signifi-cance of this purple marble as an indicator of imperial status that one emperor even took it as his name, Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (905–959), literally ‘born-in-the-purple’.

Not everyone, however, would have been satisfied with the style of these unembellished Byzantine boxes. Likeness and recognition at the grave were also thought important, especially in western Europe. Those who could afford it commissioned images of themselves to appear somewhere within the ensemble of the tomb, often a highly romanticised vision of their own body. Effigies like this began to be included at burial sites from the very early Middle Ages, starting as relatively simple figures sunken into slabs commemorating the aristocracy or clergy, evoking in front of the mourner the literal presence of the person for whom they might be praying. But these soon grew into ornate likenesses of the dead, recalling their earthly deeds. Sculptures atop royal tombs could be proudly decked in the full regalia of state, complete with golden crowns and enveloped in silken gowns, capturing the trappings of their earthly status in perpetuity. And dynamics of posture and pose, too, could be important in these monuments, used to emphasise both status and personal character. Popes and archbishops, for instance, usually appear poised in the action of blessing or are frozen in time crowning kings, one of their most respected social roles, whereas in the tomb of the warfaring nobleman William Marshal, Second Earl of Pembroke (1190–1231), now in London’s Temple Church, his effigy writhes into a twisted position as if he is poised to jump to his feet, his hand on his hilt, only just stilled at the moment of drawing his sword. The tomb immortalises the earl’s place as a bold leader of men, presenting him in constant vigilance, ready and able to do battle even after death.

38. The towering 53-metre-high mausoleum of the Ziyarid emir Qabus ibn Wushmgir, built in 1006 in the Persian city of Jorjan, now in northern Iran, near the border with Turkmenistan.

Nor did medieval tombs shy away from dealing with the raw ugliness and finitude of the deaths they marked. Skeletons abounded, fleshless skulls and bones picked out in brass monuments or on tomb-stones, suggesting that, whether because of their reassuring belief in an afterlife or an ease born of familiarity with the reality of mortality, medieval people were far less anxious about cohabiting with the visual ephemera of death than we perhaps would be. Some monuments, though, took this to the extreme. The body of Alice Chaucer (1404–1475) lies in the small church of St Mary in Ewelme, a picturesque town nestled in the Oxfordshire hills. Alice was part of a wealthy dynasty, the granddaughter of the famed poet Geoffrey Chaucer, but in her own right was an unshakable and adept political operator. She had taken a series of three husbands, each of them one rung further up the social ladder than the last – a lord, then an earl, then a duke – all of whom predeceased Alice, leaving her with a substantial fortune and expansive landholdings which she managed with rigour. The spoils of this social intelligence are best evidenced in the expensive and unusual tomb she had commissioned for herself shortly before her death. Atop this funerary monument a carved alabaster effigy of Alice lies prone on a sculpted pillow supported by angels. She smiles peacefully, wearing a rich cloak and small coronet that indicates her lofty position as duchess. Around her left forearm is a small band that proudly signifies her acceptance into the Order of the Garter, the highest chivalric honour that could be bestowed by the king and which at the time was almost never granted to a woman. She is laden with the symbols of her living achievements, the frills of finery and office. But beneath this idealised figure astute viewers could peer through a small architectural grille to see a quite different alabaster image of Alice that she also had commissioned. Laid out on an intricately carved funerary shroud is her decaying corpse. The body is grotesquely stiffened, its plump flesh so drained of life as to resemble a thin canvas stretched across a rack of bones, made painfully visible beneath. Her nose is missing, her breasts have withered completely flat and her naked jaw is drawn open in rigor mortis. The only concession to worldly concerns of appearance is her stiffened right hand, which clutches the shroud across her pelvis, covering her modesty.

39. The two effigies from the alabaster tomb of Alice Chaucer (1404–1475) in St Mary’s Church, Ewelme, Oxfordshire.

This seems a surprising image for Alice to have chosen to be presented to the world, especially when set against the idealised figure above. Yet such a comparison was precisely the point of a tomb like this. The lower effigy sets up an elegant contrast, a binary in death between Alice’s two bodies, earthly success set against earthly decay. And in so doing it reminded the viewer of the constantly pivoting status of any such medieval tomb: at that very moment Alice was both a humble, wasting bag of bones and an abstracted soul awaiting heavenly judgement. It was only through a visitor’s presence at her side, revelling in her material legacy and praying by her wasted body, that she might eventually achieve ultimate salvation in heaven.

Alice Chaucer’s grisly tomb was only one of a much larger group of late medieval artworks that sought to seize back some aesthetic potential from the tough realities of life in the Middle Ages. Take the opening stanzas of the Middle English poem The Dance of Death, by John Lydgate, the same author who wrote so eloquently about the cruel spinning of Fortuna’s Wheel. Writing in the early fifteenth century, his work formed a central part of an emerging late medieval interest in the macabre. There was, the poem’s first lines suggest, both a frequency and a universality in the way people saw death:

O ʒee folkes / harde herted as a stone

Which to the world / haue al your aduertence

Like as hit sholde / laste euere in oone

Where ys ʒoure witte / Where ys ʒoure prouidence

To see a forne the sodeyne / vyolence

Of cruel dethe / that ben so wyse and sage

Which sleeth allas / by stroke of pestilence

Both ʒonge and olde / of low and hie parage.

Dethe spareth not / low ne hye degre

Popes kynges / ne worthi Emperowrs

O you people, hard-hearted as a stone

Who to the world devote all your attention

As if it should last forever and anon.

Where is your reason? Where is your wisdom?

To see afore you the sudden violence

Of cruel Death, who is so wise and sage,

Who slays all by stroke of pestilence

Both young and old, of low and high descent.

Death spares not low nor high degree

Popes, Kings, nor worthy Emperors.

But rather than presenting his poem exclusively as a mournful lament of his time, Lydgate goes on to extract broader moral ammunition from this supposedly ghastly situation. The piece continues as a tragi-comic rumination on the power of dying, phrased through a series of unfolding dialogues between people of different social status – from an emperor and king down to a labourer and a child – with a strange, skeletal personification of Death, who beckons them in turn to dance. Nobody can avoid Death’s hand. Mankind is ‘nowght elles but transitorie’ (‘nothing else but transitory’), all eventually turned ‘to dede asshes’ (‘to dead ashes’). But there is a certain frivolity to Lydgate’s touch. While undeniably dark in tone, he laces a subtle social commentary throughout the responses of his high-born and lowly characters, all keen to turn down Death’s worrying invitation to dance – to die – as quickly as possible. When the figure of the Sergeant, for instance, is requested to join, he replies with pastiched pomposity that Death should not dare challenge an officer of such high state to engage in something so shallow. The Astronomer tries to forecast a reason in the stars not to join the deathly revellers. The womanising Squire only agrees to follow death’s lead once he has had the opportunity to bid farewell to his ‘ladyes’. And the King ends up admitting to Death that he actually does not know how to dance at all.

40. A detail from a Dance of Death painted on the walls of the Church of the Holy Trinity in Hrastovlje, Slovenia, by the artist Janez iz Kastva at the end of the fifteenth century.

Lydgate’s poem was based on the most famous and perhaps the earliest example of this genre, a French danse macabre that he had seen in 1426, when visiting Les Innocents, the largest cemetery in medieval Paris. This was no quiet, austere burial ground but a busy and unashamedly communal space, a site for mass graves of the poor and host to larger public events for the people of Paris, from markets to feast-day processions. Lydgate had found the poem there not written in a book but painted as a mural that grandly stretched across several walls of the cloister-shaped charnel houses that flanked the edges of the cemetery. Inside these half-open buildings the rafters were packed with the skeletons and skulls of Les Innocents’ longer-term residents, excavated to clear space for new bodies in the central burial ground itself. But directly below these bones, along the charnel houses’ inner walls, the poem and an elaborate illustration of Death’s dance played out. The late eighteenth-century modernisation of Paris saw Les Innocents destroyed, but we get a good sense of the mural from several others painted around the same time, and which proved especially popular on the walls of churches in central Europe and the Baltic. Frolicking skeletons hop and spin along the brickwork, reaching out their hands to grasp the anxious caricatures of the poem, a continuous band of men and women, arms interlaced, each dragged along in the steps of Death’s final dance.

Some medieval objects went even further than these murals in their playful intertwining of death and skeletal bones. Baldassare degli Embriachi, a fourteenth-century Florentine sculptor, achieved remarkable success crafting a wide range of luxury objects whose outsides were actually formed from decorated animal bone itself. Their trademark styles contrasted inlaid pieces of wood, horn, hippopotamus teeth and cow and horse bone, combined into intricate patterned panels and tessellated figural vignettes. Hundreds of objects survive from the Embriachi workshops, which relocated from Florence to Venice in the 1390s: small crucifixes, rectangular boxes, circular caskets, figural triptychs, a doubled chess and backgammon board, even enormous pinnacled altarpieces, all formed from this same boney style. But the Embriachi were in turn trading off the popularity of other small objects carved from an even more luxurious material, ivory, thought similar in look to bone but far more expensive. It was valued by high-status patrons and artisans alike and represented an obvious luxury. Whether imported from African elephants or the tusks of walruses on the arctic edges of northern Europe, it was the material stuff of the extremes of the known world, only reaching the central Mediterranean after travelling substantial distances. We know, therefore, that macabre imagery fixating on skeletons and skulls in the same deathly manner as Lydgate’s poem was no mere joke when we find it carved from this valuable material. One such sculpture, made towards the end of the fifteenth century, was perhaps designed to sit at the end of a string of rosary beads. At first glance it appears to show a simple scene of young love in miniature, a couple caught kissing, the woman rebuffing or perhaps encouraging the man’s wandering hands at her chest. But upon flipping this little object around in our fingers, we discover a remarkably different type of image. A triumphal skeleton is poised tall as if he has just emerged from the grave itself. His flesh is half gone from his body, the creamy white of the ivory tusk standing in perfectly for the bleached pallor of his human bones, and he holds a banner emblazoned in French, EN VOVS MIRES TES Q IE SUI SERES, ‘recognise in me what you will soon be’. The jarring switch from the follies of youth to galloping death, and back again should you wish to give the bead another spin, brings both a sense of gallows humour and a serious jolt: life is fleeting, live it well.

41. A carved ivory rosary bead showing a kissing couple and a skeleton holding a banner, made at the very end of the fifteenth century, probably in northern France.

To the modern mind such trinkets, like the buildings at Les Innocents, packed with skulls and bedecked with the splayed skeletal remains of cadavers, feel rather graphic and unrelenting. Whether crossing through town or simply looking down at a rosary, the violence and impending doom of medieval bones seem to have met the eye uncomfortably often. But mediated by a firm belief in the afterlife, as well as a far more proximate relationship to the realities of death, these representations would not have had the same shocking impact on their original owners as they have on us. True, there is no doubt that the bones were morbid things, irrevocably associated with death, the pain of grief, the sorrow of mourning. But to see this as a gruesome medieval obsession is wrong. More apparent to medieval men and women would have been the sophisticated range of ways one could approach bones. Fearful yes, but also respectful, hopeful, even playful.