On 17 August 1308, from her bed in the central Italian monastery of Santa Croce in Montefalco, abbess Chiara Vengente breathed her last. The precise cause of her death was not recorded by the nuns who had gathered around her, hoping to ensure the safe passing of a woman who had acted as their spiritual guide for some eighteen years. But one thing was clear to sisters Francesca, Illuminata, Marina, Catherine and Helen as they stood at the dying abbess’s side. Christ was in Chiara’s heart. Of this she had been particularly insistent as her health declined, often pronouncing that she felt him in there, nourishing her. So when, after her death, Chiara’s body seemed miraculously to resist the intense heat of Italy in August, refusing for a full five days to decay, rot or succumb to even the slightest malodorousness, the sisters decided to take their abbess at her word. They cut her open, removed her heart and put it in a box.

The nuns were unlikely to have been able to navigate particularly precisely inside Chiara. Some may have previously embalmed sisters past with apothecary’s herbs and spices. But like most untrained venturers into the body’s innards, they would probably have known little more than an approximation of where Chiara’s heart was and roughly what it might have looked like. We do not know if they even expected to find anything particularly special within their abbess’s uncorrupted body. Rather than a precise anatomical intention, they seem to have been following more other-worldly instincts.

The next day, after evening prayers, Sister Francesca felt compelled to return to the box. For some reason she was not satisfied by the first impromptu post-mortem and, intent on searching ever deeper inside Chiara’s increasingly holy remains, she cut the heart in two with a razor to examine its contents. It was at this moment that Francesca realised that the sisters’ searches were to have deep spiritual reward. Inside the heart she found a tiny sculpted image of Christ on the cross and, alongside it, a whole collection of miniature objects associated with the Passion, from the nails hammered into Christ’s body and the whip of his flagellation to the lance of the soldier Longinus which had pierced deep into the crucified Christ’s side. But these miniatures were not crafted from traditional artists’ materials, from metal, wood, ceramic or ivory. They were wrought from the flesh of Chiara’s heart itself.

The miraculous organ and its contents were immediately brought before Church authorities. Some were sceptical, but a small cult of devotees formed who were certain that Chiara’s heart had been singled out by holy forces, a sign of her exceptional religious steadfastness and foresight. In the decades and centuries that followed, paintings were commissioned to adorn the sisters’ church showing Christ himself planting a life-size cross directly into Chiara’s chest. Prints were made of the heart and its contents, in order that word might spread of the miraculous occurrence. Finally, after several failed attempts, in 1881 Pope Leo XIII confirmed Chiara’s canonisation as a saint of the Catholic Church. Her heart, complete with its muscled crucifix, sits today inside a large, ornate metal reliquary on the church’s high altar at Montefalco. Blackened over time, it is still preserved without rot or decay. Whether this was granted by some heavenly consent or a more natural process of desiccation is a decision for the beholder.

Of all the places where Christ could dwell within Santa Chiara da Montefalco’s body, why did it make sense to the sisters of Santa Croce, indeed to the saint herself, that he might have miraculously materialised within her heart? What was it about the organ that enticed sister Francesca to slice deeper into its chambers? And what else could this central, vital body part prompt in the minds of medieval people?

At the very simplest level, the heart is the internal organ whose presence in the body we can sense most acutely. Beating away inside our chests, it is one of the only things from the inside of ourselves that we can actually feel. Our stomachs might occasionally clench or let out an embarrassing gurgle, but this is nothing compared with the pumping of the heart in the chest, its pulse sounding loudly in our ears after sudden excitement, during intense exercise or in response to overwhelming fear. The insistent nature of this internal animation meant that, even in an age before sophisticated scanning of the interior, medical practitioners still placed remarkable importance on the heart and its functions.

The heritage of the classical Greek and Roman worlds played an influential role when it came to understanding the organ. Particularly pivotal were the writings of Aristotle, who in a treatise titled De anima, ‘On the Soul’, followed Plato in claiming that it was not the spontaneous action of the body’s organs that controlled human movement and intellect but the governing force of the soul. But, unlike Plato, Aristotle did not locate it in the brain, arguing instead that the sentient soul dwelt within the heart. It was from there, not the head, he thought, that all human animation and desire emanated, a producer of both motion and emotion. Apparently following the evidence of dissected early-stage chicken embryos, the ancient Greeks also considered the heart to be the first organ formed during the development of a human foetus in the womb. And later, writers such as Galen and Ibn Sina expanded these theories to argue that it was also the source of the body’s healing power and generative growth. For medieval thinkers in the Aristotelian mould, the heart was considered by some distance to be the body’s principal and most powerful part, its theoretical core, a proxy originator of action and understanding.

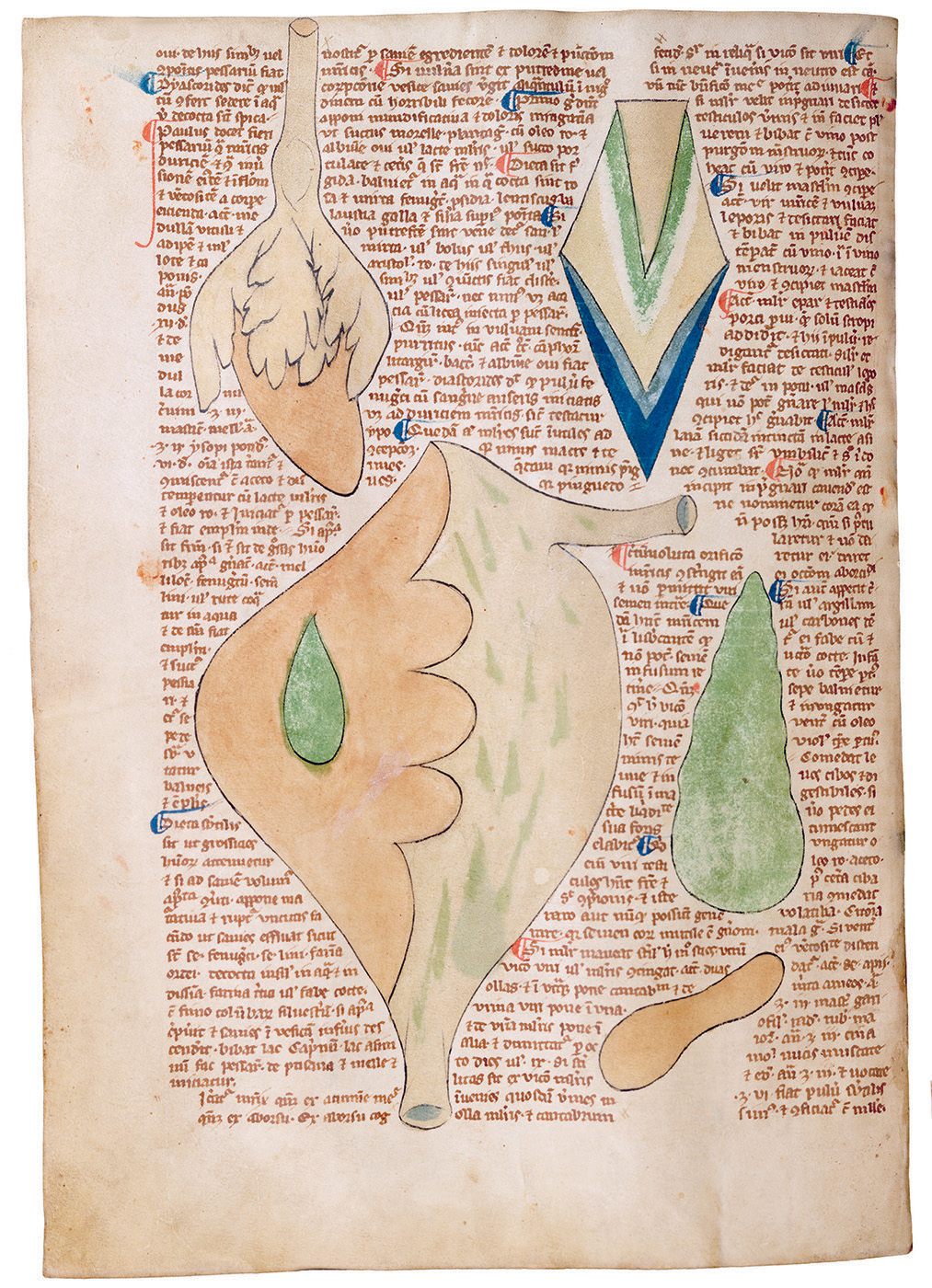

Despite this significant position as the house of the human soul, however, the heart played only a relatively small part in the actualities of medieval medical practice. It was certainly depicted in medical treatises. A thirteenth-century English miscellany shows it nestled among the text of the page alongside various other bundles of internal organs, the red lobes of its lower ventricles contrasted with the feathery whiteness of the upper atria and the long tube of the vena cava. Nonetheless, the heart’s concerns and cures tended to feature in such books only tangentially to treatments that were really focusing on other bodily concerns, like the general functions of the abdomen or the processes of a fever in which the heart was thought to play a small part. Even within these writings the heart’s precise shape, size and function fluctuate: some described it as round, while others conceived of it as more oblong and others still thought it triangular in its features, pointy like a pyramid.

One thing theorists did agree on was that the heart was of great consequence for bodily heat. The fiery core of the body, it was likened to a glowing internal sun from which other organs might receive their nourishing warmth. With warmth and coldness fixed as one of medieval humorism’s key dichotomies, the heart was also hugely significant for the overall humoral equilibrium that the body needed to maintain. If its complexion was to fall into imbalance, the body was at particular risk of dangerous failure. Signs of such impending disaster included both an overly rapid pulse or a deathly weakening of its beat, and heart murmurs and tremors were known to potentially signify an impending cardiac arrest. As well as being heralded by these physical symptoms, attacks of the heart were also conceived of as deeply emotive things, brought on by extreme changes in mood, especially shock or quickening anger. In these instances medics knew there was little that could be done to relieve a patient. Some curative substances from the physician’s toolkit were occasionally recommended to treat an ailing heart, from valuable gold and pearls to more mundane herbs and spices, especially sweet and pungent plants and syrups made from sugar and violets. Yet on the whole these measures were deemed of little use. The doctor was thought extremely lucky if they managed to revive such a stricken victim, and lists of heart cures in medical compendia read in a distinctly melancholic tone, as if to suggest that the patient was already lost.

42. An image of many of the body’s vital organs, from a Latin medical manuscript made in thirteenth-century England. The heart is shown in the upper left, surrounded by text.

This paucity of effective heart medicine was, in essence, down to the now familiar dominance of classical texts such as those of Aristotle, Galen and Ibn Sina. These writings claimed to understand the heart’s semi-spiritual contents in totality and consequently dampened further attempts to search out the detail of its actual inner mechanics. Virtually no systematic explorations of the heart appear to have been undertaken in the period, and little was known of its specific functions: neither the independence of its ventricles nor the doubled pattern of its pumping. It was not until investigations in the seventeenth century by the English anatomist William Harvey (1578–1657) that the heart was even understood to be part of a looping circulatory system in which blood rotated around the body. Prior to this, the obvious bodily sensations of beating and bleeding meant that physicians had quite easily traced blood leaving the heart, transported outwards through the extending arteries and capillaries towards the body’s extremities, but they had not yet rounded the circle and traced the heart’s veinous and arterial tracks back from the limbs to the pump. This one-way thinking prompted a far more open conception of the organ as porous and permeable. It was not shut off neatly in a sealed circuit from the rest of the body or the outside world. Rather, matters of the heart were thought to be equally affected by external influences as concrete as a lance or as conceptual as love, an idea that was to have a profound impact on all sorts of bodily thinking, from the anatomical to the poetic.

Modern language is deeply suffused with the long-standing association of the heart with emotional states. We talk of a heart fit to burst, learn things by heart, engage in heart-to-hearts or have our heart set on something. If we are emotionally committed to an idea, we can be heartfelt in our expression of it. We experience heartache, a form of pain somehow both physical and emotional at once. And when expressing negativity we can be heartless, do things only half-heartedly or express a change of heart altogether. Many of these terms are filtered through Europe’s dialects past. We might take on the emotional posture of ‘courage’, itself from the Old French for heart, coeur. Likewise, the kindly word ‘cordial’ stems from the Latin for heart, cor or cordis, from where we also get the verb ‘record’, our heart literally the inscribed register of our emotions. Even the very concept of something having a ‘core’, evolved from the same Latin roots, suggests the heart to be at the very centre of all things.

This expressive language of the heart, so fruitful and evocative in its variations, was well known and much used by medieval thinkers. Authors in particular agreed that of all the different emotions to which the heart might align, love was its predominant and most forceful domain. The tenth-century Jewish physician and poet Moses Ben Abraham Dar‘i, for instance, revelled in the idea of the heart as not just a passive agent but an alert and active romantic force. Reflecting a much-invoked hierarchy of sensory affection, his Judeo-Arabic verses played with the notion that, although sight was the sense through which one might seek out one’s beloved, it was the heart that ultimately guided love:

To the one who asks me to reveal the name of my beloved,

I cry out: ‘You suffer from a blind heart!’

For when the light in one’s eyes grows dim,

the eyes of the heart will always begin to see.

We can observe this same pairing of hearts and eyes in various poetic movements of the period, especially the Troubadour romance lyrics penned in the Old Occitan language of central and southern France. One such author, Giraut de Bornelh, writing in the 1180s, was clear that he too saw the heart as the true sentinel of feeling:

Tarn cum los oills el cor ama parvenza

Car li oill son del cor drogoman

E ill oill van vezer

Lo cal cor plaz retener

So through the eyes love attains the heart.

For the eyes are the scouts of the heart,

And the eyes go searching

For what would please the heart to possess.

From the late eleventh century onwards, poems and songs in this tradition helped shape an entirely new vision of medieval love. Contrasting with wanton lust or more casual styles of ill-intentioned encounter that easily left lovers spurned and dejected, this model of affection was billed as distinctly honest and wholesome. It has been dubbed ‘courtly love’, a highly conventionalised amorousness which over the course of the later Middle Ages rose to widespread popularity. Whether following the dramatic tales of daring courtiers or the twists and turns of separated, longing lovers, the literature of this chivalrous romance often followed predictably chaste yet ardent patterns: couples spy each other from a distance and long for each other from afar, the man attempts to woo the lady with his dramatic heroism, and she finally consents, consummating their secret tryst. In Europe, the Troubadours and their German counterparts, the Minnesänger – literally ‘courtly love singers’ – found themselves chroniclers of this burgeoning aristocratic culture. It attached great importance to the rituals and niceties of courtship, and above much else it set at its core the different romantic movements of the heart.

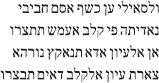

A songbook made in Zürich some time between 1300 and 1340 for the Manesse family, a dynasty of prestigious merchants, shows just how high up the social ladder this poetical interest in matters of love and the heart went. At over 400 pages long, the book represents the most complete and comprehensive collection of ballads in the medieval German dialect of Mittelhochdeutsch, containing almost 6,000 verses from the work of 140 poets. Intriguingly, these texts are not arranged chronologically, or according to a particular poem’s popularity. Instead they follow their authors’ social rank, from the writing of kings, dukes and counts all the way down to minstrels, Jews and mere commoners. At the top of this pecking order is the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Heinrich VI (1165–1197), who in his youth wrote a series of romantic poems that open the book and which marvel for the reader at the sheer heart-rending power of love. No amount of wealth or political might, Heinrich claims, can compare to the sensations aroused in him by his beloved:

43. Three portraits of courtly love poets from the fourteenth-century Codex Manesse: on the left Herr Konrad von Altstetten, in the middle Graf Albrecht von Heigerloch, and on the right Herr Ulrich von Lichtenstein.

Ich mich ir verzige,

Ich verzige mich e der crone … Si hat mich mit ir tugende

gemachet leides vri

Ich kom nie so verre sit ir iugende

Ir enwere min stetes herze ie nahe bi

Before I give her up

I would give up the crown …

She has with her force

Let my sorrow free,

I have never since youth been so far

Without my faithful heart near by.

As well as such dramatic stanzas, the spoils of these many German love songs are visualised across the codex’s decorated pages in the form of miniature author portraits showing each of its romantic poets in turn. Some, such as the chivalrous Herr Konrad von Altstetten, lounge in their lovers’ arms beneath suggestively flowering trees after what we can only presume has been a rather successful poetic recital. Others are shown in the midst of dramatic heroic action. Herr Ulrich von Lichtenstein appears armoured under the crest of Venus, a full-scale figure of the goddess mounted atop his helmet as he rises forth from the froth of the waves above a pair of battling sea monsters. The accompanying poem tells us that, as Herr Ulrich travelled to meet his lady love through northern Italy and Austria towards Bohemia, he battled victoriously no fewer than three hundred times. Knights, kings, even emperors, it seems, found the heart a compelling metaphor for the twin pillars of courtly love: an enduring, softer sense of romance and a more overtly masculine, aggressive performance of passion.

On the other side of the same coin, as an active symbol of the body’s spiritual feelings and emotional states, a heart could also betray its owner by exhibiting moral flaws that might otherwise have escaped notice. A tale from the vita of Saint Anthony of Padua – he of the silver tongue and golden jaw reliquary – records his attendance at the burial of a rich man in Tuscany. All of a sudden, in the middle of the funeral cortège no less, Anthony received divine inspiration that the man on his way to the grave was unfit to be buried in sacred ground. Crying out, calling a halt to the procession of the corpse, the saint proclaimed that the man’s soul was damned and that the body itself, if searched, would be found to hold no heart within it. We know from the historical record that Tuscan funerary rituals like this had long been a part of the social pageantry of local rule and order, holding profound significance among the rich. Unsurprisingly, then, Anthony’s proclamation caused horror and commotion. When called upon to explain himself, the saint turned to scripture, quoting the Gospel of Luke (12:34): ubi enim thesaurus vester est ibi et cor vestrum erit, ‘for where your treasure is, there your heart will also be.’ Taking Anthony’s turn of phrase as literally as Santa Chiara’s fellow nuns, the onlookers promptly called a surgeon to open the dead man’s chest, and, astoundingly, it was found to be totally empty. Only then did Anthony reveal to the assembled officials that they should pay a visit to the rich man’s safe, a chest hidden beneath his bed, where they would find the missing organ nestled comfortably among his piles of gold. Sure enough, it is there that the heart was discovered, and the ungenerous miser was dragged by a cart along a nearby river and buried unceremoniously at its edge, double-crossed by his own body.

Later Italian literature continued to place the heart at the centre of similar gruesome stories of good and evil. The Tuscan author Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), writing in his famous Decameron – a collection of stories told by a group of young men and women sitting out a nearby plague in a Florentine countryside villa – included several hearty twists among his tales of trysting lovers. In one story, that of Ghismonda, daughter of the prince of Salerno, the princess tries to resist the well-bred husbands chosen for her by her father. When she enters into an illicit affair with a lover, her father has him killed and his heart sent to his daughter in a goblet. In true melodramatic style Ghismonda cries enough tears to fill the goblet, mixes them with poison and drinks the entire concoction to end her own life. In another of Boccaccio’s tales a knight discovers that his wife has been unfaithful to him with another man. He promptly kills the lover in a joust and cuts out his heart, but he does not stop there. Giving the organ to his chef, he orders that it be made into a ragout for his unknowing wife:

Il cuoco gli mandò il manicaretto, il quale egli fece porre davanti alla donna, sé mostrando quella sera svogliato, e lodogliele molto. La donna, che svogliata non era, ne cominciò a mangiare e parvele buono, per la qual cosa ella il mangiò tutto.

Come il cavaliere ebbe veduto che la donna tutto l’ebbe mangiato, disse: ‘Donna, chente v’è paruta questa vivanda?’

La donna rispose: ‘Monsignore, in buona fé ella m’è piaciuta molto’.

‘Se m’aiti Iddio’, disse il cavaliere ‘io il vi credo, né me ne maraviglio se morto v’è piaciuto ciò che vivo piú che altra cosa vi piacque’.

La donna, udito questo, alquanto stette, poi disse: ‘Come? che cosa è questa che voi m’avete fatta mangiare?’

Il cavalier rispose: ‘Quello che voi avete mangiato è stato vera-mente il cuore di messer Guiglielmo Guardastagno, il qual voi come disleal femina tanto amavate. E sappiate di certo che egli è stato desso, per ciò che io con queste mani gliele strappai, poco avanti che io tornassi, del petto!’

The cook set the ragout before him but, feigning that he wished to eat no more that evening, he had it passed to the lady and highly commended it. The Lady took some of it and found it so good that she ate the dish whole.

Seeing she had eaten it all, the knight asked, ‘Madam, how did you like the dish?’

The Lady replied, ‘In good faith, my lord, a lot.’

‘I believe it!’, returned the knight. ‘It is no wonder you should enjoy dead that which while living you enjoyed more than anything else.’

For a while the lady was silent, then asked, ‘What do you mean? What is this you have made me to eat?’

The Knight replied, ‘That which you have eaten was truly the heart of Sir Guiglielmo Guardastagno, who you, disloyal woman that you are, loved. And I know for sure: a short while before I came back, I plucked it from his breast with my own hands!’

In the rich literary tricks they played with the heart, medieval authors were harnessing the organ’s vital power through metaphors of love, but also passion, greed and vengeance. Just as beheading was a potent symbol of social control amid the Body Politic, when reaching for a body part to represent both the soaring highs and punishing lows of human existence – at once lovingly kind and viciously cruel – it was difficult to compete with the body’s supreme centre, the heart’s intense emotional valency assured through both medical thought and popular romance.

It is within the visual repertoire that accompanies these courtly tales of love, loss and rejection that the first medieval images of the heart began to appear outside of the therapeutic realm. These literary hearts, however, do not look as we might expect.

One of the earliest is found in a French manuscript of the 1250s containing an epic poem with the peculiar name Le Roman de la Poire, ‘The Romance of the Pear’. As a story, it is relatively simple. The pear is a symbolic and erotically potent fruit given to the author by a lady, his estranged lover. Intoxicated by its taste and full of an unquenchable desire, he searches her out in Paris, conversing en route with human personifications of several emotions and virtues – Beauty, Loyalty, Mercy – before eventually finding his beloved and singing to her his tale. The moment when the two lovers first set eyes on each other is a key juncture in many such courtly narratives, but in the Roman de la Poire this look is not portrayed as a literal glance. It features as yet another personification: a kneeling messenger who, much like the active Troubadour eyes of Giraut de Bornelh, scurries between the lovers. His name is Douz Regart, a punning name literally meaning ‘sweet looks’, and in one illustrated manuscript of the poem an artist has preserved his image within the calligraphic curve of an illuminated capital ‘S’. Douz is shown kneeling before the lady offering the author’s heart, holding it up to her chest as if it were communing directly with her own, the ultimate symbol of shared affection.

44. Douz Regart, a personification of the lover’s gaze, holding a heart in a thirteenth-century French manuscript of the Roman de la Poire.

On closer inspection, though, the heart held by Douz looks more like the story’s eponymous pear than anything we might today recognise as a shape symbolising love. It is no neatly curved, evenly formed, symmetrical ♥, of the likes we are used to seeing on Valentine’s Day cards or bursting forth from the chests of swooning cartoon characters. Partly, this oblong heart was matching medical descriptions such as that of Ibn Sina, who described the organ as ad pineam, ‘like a pine cone’. But this is also because for most of the Middle Ages the ♥ as a shape held no specific link with the organ of the heart. ♥s are certainly found on all sorts of medieval objects, but simply as one decorative motif among many alongside vine scrolls, hatched lines, chequerboard patterns or circular spirals.

It is still unclear precisely how this formalised yet abstract shape actually came to stand for the organ and emotions of the heart as it does now. Perhaps it was an association with the leaves of creeping ivy or other plants thought at the time to be aphrodisiacs. Or perhaps the pre-existing ornamental ♥ shape simply grew quite naturally to fit descriptions of a bicameral organ, more pointed at one end than the other. Either way, the use of this symbol seems to have concretised only towards the very end of the medieval period, when it featured in several early European printed images. The new technology of print meant that from the 1450s onwards images could be created far more easily and spread far more quickly across different regions and audiences. This broad circulation seems to have been the thing to seal common agreement that the ♥ symbol represented the heart, especially its amorous properties. From these novel and newly abundant images, especially printed playing cards, the sign began quickly appearing on all manner of later medieval and early renaissance objects. Tokens of romantic affection like decorated boxes opened to reveal secret symbolic affections in the form of inscribed or embossed hearts. Combs gifted to one’s beloved might place a heart at their centre, ensuring that a suitor would be squarely in the mind of his lady while at her toilette. And in some cases entire artworks were even crafted to fit the symbol, like a series of cordiform books, a speciality of the Netherlands, which contained within their heart-shaped pages all sorts of accumulated images, poems and courtly songs of love and romantic encounter. Few actual love letters or other literary declarations of affection tend to survive from the Middle Ages beyond the grand narratives of courtly love stories, and these heart-shaped trinkets offer us a rare glimpse into what must have been a busy and intimate network of personal affection.

In all of these cases the image of the heart helpfully gave medieval people a way of animating types of otherwise unexpressed inner feeling, the organ acting as sort of bodily spokesperson. Yet just as a heart of stone might give away its miserly owner, so it was well understood that exchanging affections of the heart in this way also left one vulnerable. No matter how freely romantic affection was presented by one party, there had to be a receptive heart to accept it on the other side. Success in these cordial relationships was often represented by two hearts on evenly balanced scales, weighed up as if providing definitive proof of lovers’ good intentions. But inevitably, in some cases, the receiver’s heart was empty, light and unresponsive. In a small circular roundel from a German tapestry made in around 1360, a couple weigh their hearts against each other, but the scales fall lopsided in unrequited affection. Raising a finger weakly in objection, the man does not look best pleased. Pointing to her heart, the lighter of the two, his partner barely seems bothered at all.

45. Six circular details from a German medallion tapestry made in around 1360, showing various scenes of lovers. In the upper centre a lover gives over a winged heart to the personification of courtly love, Frau Minne, who stabs it with an arrow. In the lower right two lovers weigh their imbalanced hearts against each other.

Sadness like this could ripple outwards from the heart to be felt by the whole body, physically as well as emotionally. While feelings like anger and desire were thought to be produced by the heart’s inherent heat spreading rapidly to the ends of the fingers and toes, other passions such as sorrow or envy were met with a chilling vacuum, leaving the heart hard and heavy. As one fourteenth-century Italian author, Jacopo da Milano, asked himself in frustration: ‘O cor plusquam lapideum, o cor non cor, cur non accenderis ex amore’, ‘Oh heart, harder than stone, oh heart which is not a heart, why are you not enflamed with love!’ In such romantic metaphors, the heart itself could be just as vocal, mourning, lamenting, sighing or even taking on fully blown wounds, ensnared and broken under emotional torture. A print from Germany designed in the 1480s by the master Caspar von Regensburg, shows the figure of Frau Minne, ‘Lady Courtly Love’, a Venus-like personification of love to whom German artists often turned when wishing to depict the antics of the beloved. Standing defiantly in the centre of the print, stamping, slashing and piercing, Minne is surrounded by no fewer than nineteen hearts – here fully ♥-shaped – which she is in the process of violently abusing. One is burned at a stake, others pincered, hooked, sawn in two, clapped shut in a bear trap, crushed in a press and shot through by arrows, knives and a lance. There is little that Minne’s helpless, miniaturised lover can do but look on. Kneeling below her with his hands wide open, he beseeches her pathetically to stop with a hopeful rhyming triplet:

O freulein hübsch und fein.

Erloß Mich auß der pein

und schleus mich in die arm dein.

Oh Fräulein, pretty and fine!

Release me from the pain

And take me in your arms!

The plea falls on deaf ears, and at the bottom of the print in a contemporary fifteenth-century hand, perhaps that of its original late medieval owner, a verdict is delivered. ‘Du Narr’, they write: ‘You Fool’.

46. The Venus-like Frau Minne, torturing the hearts of her beloved in nineteen different ways, in a print by Master Casper von Regensburg, made around 1485.

As well as this seam of secular amorousness running through medieval notions of the heart, another type of love, perhaps even stronger, also emerged in the Middle Ages as a powerful force across Europe. This was religious love, an important issue for doctrinarians of all faiths. Jewish thinkers had long seen a love of God as at once a duty and a measure of spiritual mettle. As the Spanish rabbinic authority and philosopher Maimonides (1138–1204) viewed it, it was the main goal of Jewish law to improve the soul through knowledge, and the greater the knowledge, the greater the thirst of the faithful to love God with a burning intensity. Influential for parallel ideas in Christianity were the writings of Saint Augustine, who extended earlier classical conceptions of love and friendship to cover two specific types of Christian love. On the one hand stood cupiditas, a worldly love, a self-important love of other people and a deeply human desire to possess things. Linked to the mischievous classical Cupid – as well as to the covetous word ‘cupidity’ – it indicated a certain frivolousness, a profane and dangerous concern with the material world. Contrasting with this was another concept, caritas. This idea – from which evolved the English word ‘charity’ – connoted an opposite, far more nourishing, type of love, one that good folk should hold for each other and, more importantly, for God.

This theologically sanctioned love became particularly intertwined with the image of the heart. By the twelfth century the French theologian Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) was the first to suggest that prayers might be addressed directly to Christ’s heart itself rather than his person more generally. For Bernard, the deep wound made in Christ’s side by the lance of Saint Longinus during the crucifixion did more than just pierce his chest: it carried on through the ribs to pierce Christ’s very core. It was via such an aperture in Christ’s heart that the secrets of his heavenly soul might be revealed to mere mortals. This focus of devotion came to be known as the Cult of the Sacred Heart and saw prayers and religious sentiment thrust with a real spiritual zeal towards Christ’s inner being. By the thirteenth century the German mystic Meister Eckhart (c.1260–1328) was writing prayers that set the faithful in conversation with the heart, and even more mainstream theologians, such as the Italian author Bonaventura (c.1221–1274), wrote that a good Christian could attempt to actually live within Christ’s heart, devotionally speaking. As a spiritual tool, a concentration on Christ’s core particularly appealed to the focused lives of monks and nuns, many of whom recounted miraculous or visionary experiences that can seem quite shocking to today’s sensibilities. Heinrich Seuse, a thirteenth-century Dominican friar and religious author, wrote of creating what he called an everlasting ‘badge of love’ for God by cutting the letters IHS, a Latin abbreviation for the name of Jesus, directly into his chest above his heart. Another, Saint Catherine of Siena (c.1347–1380), laid claim to a series of miraculous levitations in which she and Christ tore out their hearts and bloodily exchanged them between their bodies.

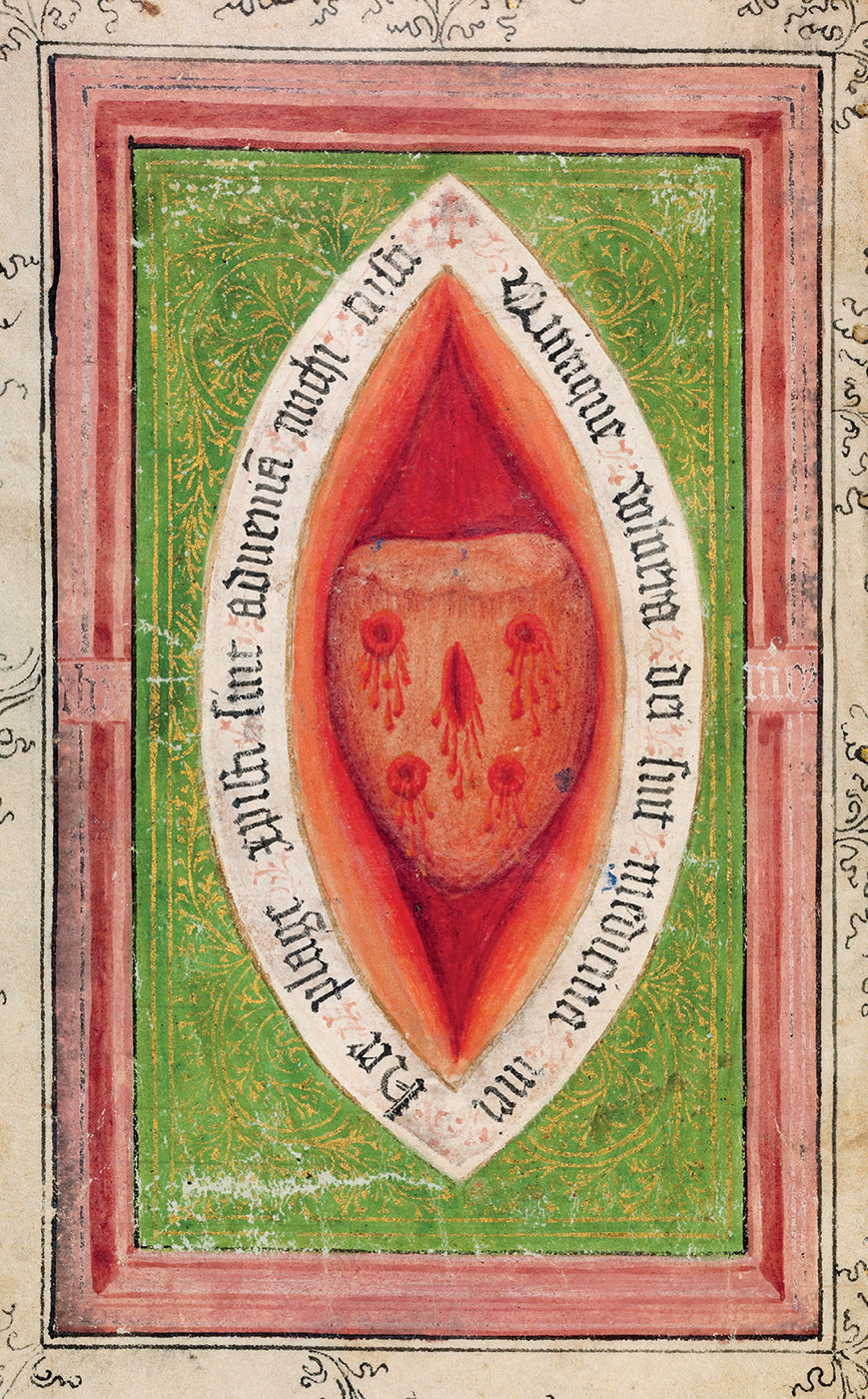

47. The heart of Christ viewed through the wound in his side, illustrated in a Book of Hours made in the Netherlands between 1405 and 1413.

Other religions at times thought just as literally about the heart’s role in loving God. Muslim commentators, such as the eighth-century historian Muhammad ibn Ishaq (c.704–767), occasionally recounted the graphic miraculous tale from the life of the Prophet, when a young Muhammad was received by angels and had his heart removed by them, ritually washed and then replaced in his chest, rendering him theologically purified and open to Qur’anic teaching. But extreme and intimate accounts of this sort were far more common in Christianity, so potent in part because the heart of Christ and the narrative of its piercing found repeated presence in everyday life. In 1424 Sigismund of Luxemburg, then Holy Roman Emperor and ruler over much of central Europe, had his extensive collection of holy relics transferred from the imperial capital of Prague to the city of Nuremberg. Included in this group was the original lance of Saint Longinus with which Christ’s side had been punctured. There were in fact several Holy Lances circulating in western Europe at the time. One was claimed to have been taken by the armies of the First Crusade in 1098 from Antioch in modern-day Turkey to Rome, where it was kept in the Vatican beneath St Peter’s Basilica. Another, or perhaps the same one, had supposedly been seen in Paris. A fourth eventually manifested in seventeenth-century Warsaw. However, the relic that was moved to Nuremberg inspired much more widespread devotion in comparison to its rivals. From the moment it set foot in the city pilgrims flocked to visit the Holy Lance at the Church of the Holy Spirit. Local residents wrote songs and poems commemorating its presence in their town, and it was exhibited publicly every year on the Feast of the Holy Lance, the second Friday after Easter, in the market-place across from the spectacular façade of Nuremberg’s Church of Our Lady, the Frauenkirche.

Perhaps the most poetic witness to the relic’s fame among Nurembergers is a small book of devotional texts gathered together by a historian and physician named Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514). Written in 1465, some forty years after the arrival of the relic in the town, the notebook is particularly interesting for a single sheet stuck into it, a small woodblock print pasted into the binding. It depicts a large heart, rendered in deep red with a thick black line marked through its centre. Above is a short phrase, also printed: Illud cor transfixum est cum lancea domini nostri Iesu Christi, ‘This heart has been pierced through by the lance of our Lord Jesus Christ’. Early prints like these were known as Speerbilder, ‘spear-pictures’, spiritual tokens purchased as souvenirs in and around Nuremberg. Here the dark slash of the image is not just printed but has been literally enacted, the heart actually pierced through. Like all Speerbilder, this was supposedly done not with the printer’s knife but by impaling the paper on the actual relic of the Holy Lance itself. These quickly printed and quickly sanctified images could be quickly sold to the visiting faithful in great numbers, imbued with the associated power of the relic’s touch. Recreated on the pages of Schedel’s book, therefore, is both an image of Christ’s heart and a replication of the actions done unto it, a penetrating reenactment of an intensely revered sacred pain.

Personal, intricate objects like this reveal more than anything that the medieval heart was a deeply intelligent organ, a unique way of linking person to person, or person to holiness. Despite little being known about its actual workings, it was still beating prominently at the centre of a medieval emotional world. And in both writing and imagery alike, it formed a symbol for expressing the very lowest lows and highest highs of religious and romantic life. To return to the case of Santa Chiara, the fervid search through her body for a barely tangible sanctity feels, in fact, like a fair reflection of the heart’s physiological and emotional roots. If the heart was open, penetrable, sensual and spiritual, where else should Christ wish to dwell within the medieval body than in the poignant house of her soul?

48. Hartmann Schedel’s Speerbilde, shown from front and back. It was pasted into his notebook in around 1465.

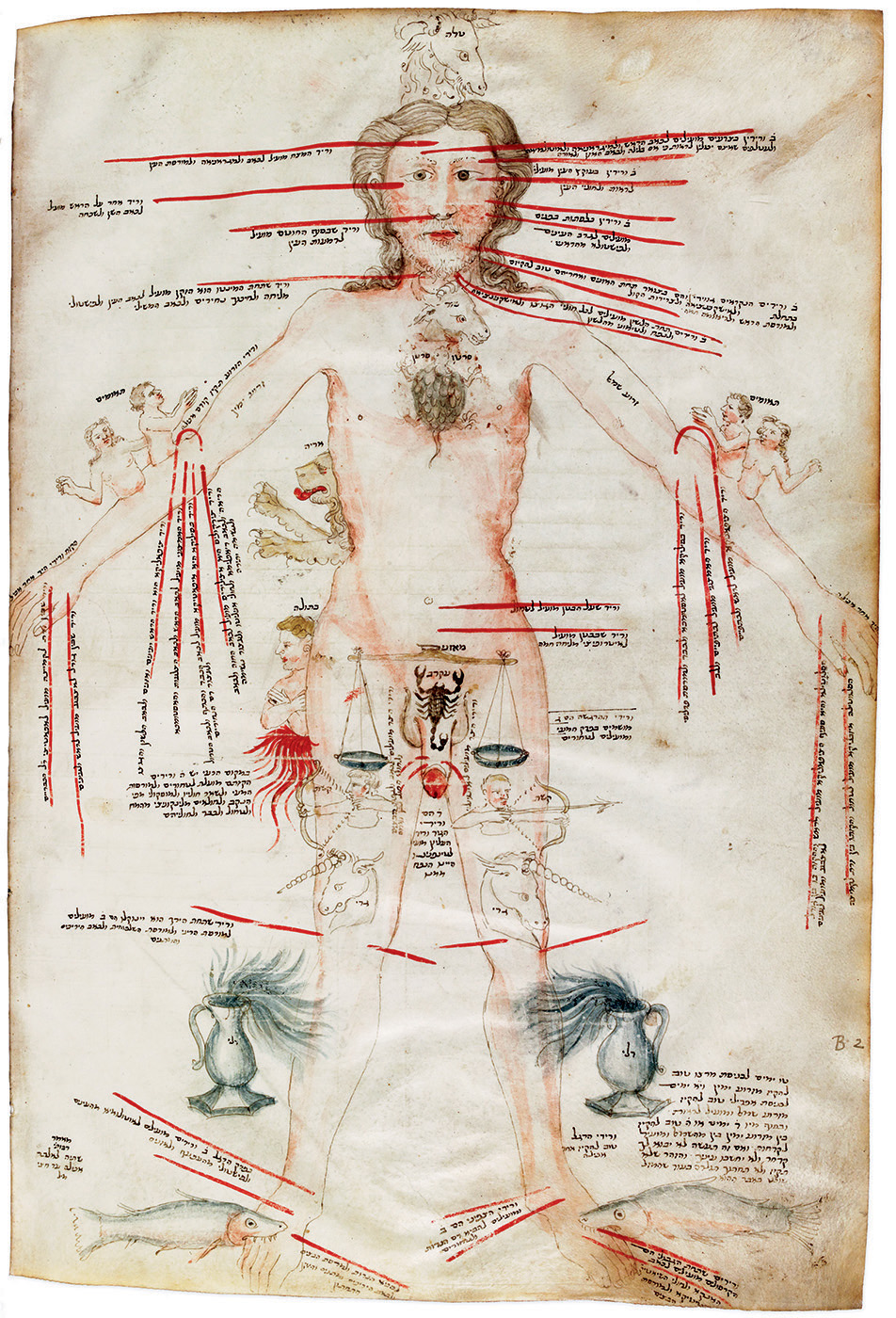

49. A blood-letting figure from a Hebrew medical miscellany, illustrated in southern France or northern Italy in the early fifteenth century.