In the basement of the British Museum sits a small ivory plaque from fourteenth-century France. The piece is tiny, only 5 centimetres by 8, small enough to fit neatly into the palm of the hand. It would probably have originally been used as a writing tablet. Paired with another small plaque of identical size, the two halves would have hinged together in the manner of a miniature book, its sculpted surface acting as a cover while recessed spaces in its back were filled with a thin coating of wax. Short notes or calculations could be inscribed into this hardened layer with a sharp stylus by its owner to record their thoughts or figure sums, before the piece was then run over a candle to melt and reset the wax page, clearing it of writing in a single swoop like a medieval Etch-a-Sketch.

The carved image on its decorated front was more permanent. It depicts a gathered collection of men and women tightly framed within three architectural niches. These courtly figures – some standing, one seated, another two on the floor – are playing a game known in the Middle Ages as Haute Coquille, ‘Hot Cockles’, or sometimes La Main Chaude, ‘The Hot Hand’, a jaunty name that masks a rather more sexualised pastime. To play, someone is blindfolded and then spanked.

In the British Museum ivory it is a young man who finds himself kneeling at the centre of the action, his head placed inside the folds of a seated woman’s skirt so he cannot see. Despite the small size of the piece his outline is delicately rendered, ghostly beneath the cloth, and we get a sense of the game’s erotic potential in the silhouette of his hand, creeping up the woman’s left thigh. The act of spanking itself is prefigured in the raised right arms of the two women behind, their exaggerated hands poised to strike him in a pair of flat, slapping swings. The game finished with the blindfolded figure guessing the identity of his or her slapper by the sting of their spank alone. If they were correct, they would be rewarded with a kiss, as shown at the ivory’s upper-right, where a victorious couple quietly smooch among the arches.

Hands are conspicuous in this piece. They touch, slap, pat, hitch, point, grope, caress, spank. The more we look, the more of them we see. The woman whose skirt the man is under rests her left hand on his head, her right at the same time pointing with a strangely elongated finger upward to the assembled crowd. The pair of spankers hitch up their skirts with grabbing motions. The bearded figure in the lower left, who presumably is up – or should that be under – next seems to be using his hands to part the crowd, edging his way between the women with flattened palms. Even the woman at the far left of the composition, a figure so peripheral as to not be granted a whole body within the bounds of the plaque, is still given a large flapping hand, tucked centrally inside the ivory’s frame. Placed in the palm of the hand, as this writing tablet often was, these details would have resonated: the ivory conveys not just the tactile extremities of the body but the sense of touch itself in action.

Medieval concepts of touch are difficult to get to grips with, full of inherent problems and contradictions. When compared with the more mystical, ethereal sensations of vision and sound, which travelled via diaphanous rays and vibrating air, or even the more tangible senses of taste and smell, touch was found right at the bottom of the sensory pile, the very basest of the five senses in the Middle Ages. Perhaps this was because it is a confusingly simultaneous sense, neither totally active nor totally receptive: in reaching out to touch something, that thing is inevitably touching you at the same time. What is happening there? Are you touching or being touched? Or both? This haptic inelegance seemed clearly ignoble in comparison to the illusive magic of sweetening song, the soft waft of a heavenly scent or the subtle gradations of vision.

On the other hand, however, the undeniable sensual immediacy that comes with touch meant that at times it could also be presented as one of the more vital of medieval sensations. Like scent, taste, sound and sight, touch was thought to function through the animating spiritus flowing through the medieval body, transferring sensory information from the surface of the skin back to the brain for cognition. But unlike these other senses, touch was sturdy, hard-headed and definitive. It could give direct and tangible presence to the world around you. The fact that touch is, of course, impossible at a distance – compared with hearing far-off sounds or seeing images on the horizon – suggested a certain thrilling proximity. It could even be viewed as the most crucial sense of all. Scholars continued to acknowledge the claim made by philosophers like Aristotle that touch was the one sense absolutely necessary for life. That is to say, an organism might exist without its other senses – might be deaf, blind, anosmic or ageusic – but without any sense of touch a being must be thought of as fundamentally lifeless, must be dead. In this way touch was used as a fundamental measure of vitality and was thought of as a diagnostic tenet in its own right in the Middle Ages. Manipulating the patient’s body to different degrees could ascertain their levels of pain, while tapping them at particular points was advised while listening for certain echoes or sounds, something still done by doctors today to gauge the health of the chest. Hands were described by medical authorities as the body’s workmen, and employing them to test the firmness of a particular body part – its swelling, texture or moisture – was all of interest in understanding the nature of a patient’s particular condition. Sickness could be keenly sensed through a doctor’s fingers.

Touching Tools

A problem emerged from the importance placed on this curative touch in the medieval medical encounter. What if a medic needed to carry out their work not with their hands but with tools? What if they needed to cut, to suture, to stitch? If touch was prized for its directness in diagnos is, was it not a problem to attend to the patient at such a state of tactile remove?

To combat this, medieval surgeons began to develop a way of thinking about their tools which conceptually merged their instruments with their own bodies. In particular, authors discussed probes, scissors, knives and other tools as direct extensions of their operator’s hands. Both Greek and Latin terminology preserve something of this inextric able bond in the very etymology of the word ‘surgery’, inherited from the Greek, kheirourgos ( ), or Latin, chirurgia, both combinations of the terms for ‘hand’ and ‘work’. In early medieval Old English texts direct conflations were made of medical tools with the people who wielded them, the terms for surgeon and surgical instrument often interchangeable with one another. And in later Middle English writings too the language of the medical professional was caught up in everyday bodily terminology. The ring finger was often also dubbed the leche fingir – from the Old English for doctor, læce – both because it was commonly used to mix and apply medicines and because its veins were thought to lead directly to the heart. Henri de Mondeville, the French surgeon whose writings on skin we have already seen vividly illustrated by the figure of a flayed man, even went so far as to describe the iron joints and blades of his surgical knives as being like a surgeon’s very own fingernails and digits. This linguistic idea could also work backwards, with surgeons writing that they themselves needed to be delicately formed in the manner of their exquisite surgical tools. The Italian medic Lanfranc of Milan (c.1245–1306) stressed the importance of a surgeon’s well-shaped hands with long small fingers, while his contemporary the Flemish author Jan Yperman (c.1260–1330), spoke of surgeons needing ‘vingheren ende lanc sterc van lichame, niet bevende’, ‘fingers extending long from the body and which do not tremble’.

), or Latin, chirurgia, both combinations of the terms for ‘hand’ and ‘work’. In early medieval Old English texts direct conflations were made of medical tools with the people who wielded them, the terms for surgeon and surgical instrument often interchangeable with one another. And in later Middle English writings too the language of the medical professional was caught up in everyday bodily terminology. The ring finger was often also dubbed the leche fingir – from the Old English for doctor, læce – both because it was commonly used to mix and apply medicines and because its veins were thought to lead directly to the heart. Henri de Mondeville, the French surgeon whose writings on skin we have already seen vividly illustrated by the figure of a flayed man, even went so far as to describe the iron joints and blades of his surgical knives as being like a surgeon’s very own fingernails and digits. This linguistic idea could also work backwards, with surgeons writing that they themselves needed to be delicately formed in the manner of their exquisite surgical tools. The Italian medic Lanfranc of Milan (c.1245–1306) stressed the importance of a surgeon’s well-shaped hands with long small fingers, while his contemporary the Flemish author Jan Yperman (c.1260–1330), spoke of surgeons needing ‘vingheren ende lanc sterc van lichame, niet bevende’, ‘fingers extending long from the body and which do not tremble’.

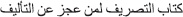

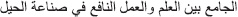

We can begin to see what these surgeons meant when we look more closely at the complicated tools that would have been used in their surgeries. Surviving instruments from the Middle Ages are exceptionally rare, not often preserved among the precious collections of objects passed down to the modern day. Even so, elaborate images in manuscripts do exist and these give at least some sense of medieval surgical instrumentation. Perhaps the most prominent of these is an influential series of treatises by al-Zahrawi, who addressed surgery in the last volume of his thirty-part book the Kitab at-Tasrif ( , known in English as The Method of Medicine). It preserves around 200 depictions of surgical tools, elongated forms slotted between passages of explanatory text. Like the illustrated skeleton of the Persian physician Mansur, whose bones are presented diagrammatically rather than realistically on the page, these images of tools are not intended to convey precise shapes and dimensions to the reader. Whether in original Arabic manuscripts, Latin translations or even later printed editions, al-Zahrawi’s instruments appear for the most part rather thin, wildly coloured and with toothed blades of exaggerated size or strange, feather-like softness. Nevertheless, such luxurious images still make clear just how important these objects were to the surgeons who wrote and arranged these books: careful time and attention have been taken to convey the ornate detailing of their grips and the subtle decoration of their ends, showcasing them as expensive, professionally crafted items.

, known in English as The Method of Medicine). It preserves around 200 depictions of surgical tools, elongated forms slotted between passages of explanatory text. Like the illustrated skeleton of the Persian physician Mansur, whose bones are presented diagrammatically rather than realistically on the page, these images of tools are not intended to convey precise shapes and dimensions to the reader. Whether in original Arabic manuscripts, Latin translations or even later printed editions, al-Zahrawi’s instruments appear for the most part rather thin, wildly coloured and with toothed blades of exaggerated size or strange, feather-like softness. Nevertheless, such luxurious images still make clear just how important these objects were to the surgeons who wrote and arranged these books: careful time and attention have been taken to convey the ornate detailing of their grips and the subtle decoration of their ends, showcasing them as expensive, professionally crafted items.

56. Surgical instruments, from a thirteenth-century copy of al-Zahrawi’s Kitab at-Tasrif.

Presenting instruments like this was also an acknowledgement that the tools of their trade formed an important part of surgery’s public face. Possession of the right equipment for the job communicated both competence and expertise, just as today the set-up of a doctor’s surgery or their impressive new diagnostic technologies might seek to tell a patient that they are in the hands of a well-trained and successful professional. Good-quality tools were so important to medieval surgeons that we frequently find them mentioned as star objects in their wills. The final testament of one Antony Copage, a surgeon in late medieval London, requested that all his steel instruments be left to his servant George on the condition that ‘he be of the same craft’. Listed alongside Copage’s valuable books, his finest clothes and even some personal keepsakes left to his wife, his surgical kit was clearly among his most prized possessions. Tools also allowed surgical guilds to regulate the field by sanctioning certain individuals to practise. These communal institutions could grow to substantial size and renown. In late medieval York, for instance, the barber-surgeons’ guild was a preeminent medical force, responsible for activities as diverse as organising annual religious plays and enfranchising newly trained members. Some amateur workers seem on occasion to have slipped through the cracks: records of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London list a carpenter by the name of Galop being called to ‘practyse surgery’ on a patient whose limb needed amputating with a saw, obviously not for his anatomical expertise but because he simply had something resembling the right equipment. Nonetheless, for approved professionals, being allowed by their community to wield their tools conferred both masterful status and social standing. Indeed, the guild’s consent could be withdrawn just as momentously as it was granted. If found transgressing the rules – failing to keep up payment of dues or dropping below certain professional standards or moral benchmarks – a member might be forbidden to practise and have their tools confiscated. To strip them of their instruments was to strip them of their very hands to work with.

Surgical instruments from the Middle Ages were even sometimes thought to possess a kind of inherent agency in their own right. For strict followers of Aristotle, for whom the ability to touch marked the difference between the living and the dead, this made little sense: a scalpel or a saw formed of cold, hard metal should have no vitality to it at all. But in the hands of the medieval creative imagination these heavy, inert tools could come alive. The designs of surviving instruments are almost always organic and extremely animated. Patterns gravitate towards foliage, with shimmering petal-shaped gilding and vine-scroll, damascened inlay. Others sport active animal features, hawk-headed handles or frilled elephantine trunks that spiral out from the main body of the design, energising their forms. Human faces and mouths also abound, sprouting from handles and joints. Such orally fixated animation is especially fitting, given that contemporary medical treatises often rhetorically referred to surgery as a biting craft, with writers returning repeatedly to the actions of ‘chewing’, ‘munching’ or ‘gnawing’ in their texts to describe both the spread of diseases and the movement of tools as they worked through the body.

These active designs align too with descriptions of instruments in contemporary literature, a fictional realm where instruments could come to life even more evocatively. In Middle English poetry, a tool like a saw – used by a number of different professionals, butchers or foresters as well as surgeons – could not only look on from its animal ends and gnaw whatever its serrated teeth cut into but could also be made to speak. A fifteenth-century manuscript from Leicestershire preserves a short poem entitled ‘The Debate of the Carpenter’s Tools’, in which a gaggle of animated objects from a woodworker’s bench debate the best way for their master to achieve prosperity and, more urgently, how their furious work might keep up with his rapacious habit for drink. After disputations from the axe, the brace and others, the saw eagerly joins the chorus, reprimanding the previous speaker, the compass, as an apologist for his inebriated master:

57. An early sixteenth-century surgical saw, probably made in western Europe, that preserves many earlier medieval features.

It is bote bost þat þou doyst blow

For thofe þou wyrke bothe dey and nyght

He wyll not the I sey þe ryght

He wones to nyghe þe alewyffe

It is but boast that you do blow

For though you work both day and night,

I say he will not prosper.

He lives too near the landlady.

The carpenter’s saw, just like the surgeon’s saws and knives, stood for hard toil and committed craft, embodying animated loyalty and artisanal common sense. As sentient speaking beings, touching the patient all over, they morphed into eloquent commentators on the surgical world they actively witnessed. One later German surgical saw, now in Vienna, offers a short poetic verse etched onto its bow. Punning on the double meaning of the German word spruch, translatable both as a ‘saw’ and as a ‘motto’, it reminds readers of the simultaneous fear and hope such tools could inspire:

Spruch:

Grausam sieht mein Gestalt herein,

Mit Angst, Schwäche und großer Pein,

Wann das Werk nun ist vollendt

Mein Schmerzen sich in Freide wendt.

Saw/Motto:

Cruel looks are in my shape here laid,

With fear, weakness and great pain,

But when the work is then all ended,

My hurting into joy is rendered.

Handy Devices

Depictions of hands appear extremely frequently in the margins of all types of medieval manuscripts, medical, fictional and poetical. In fact, they feature more than any other body part. These manicules, as they are now known, consist of slender palms that sprout sets of extremely elongated fingers, one of which will point to a particular section of text. These little hands are the remnants of medieval readers, designed deliberately to draw the eye to an important phrase, the start of an especially consequential chapter or even just a place in the text to which, for reasons now forgotten, a book’s owner wished to return at some point in the future. As markers, they are often appended to personalised notes also made in the margins and might have been added by multiple people at multiple moments in the history of a manuscript, building up a layered sense of a book’s pattern of use.

These marginal hands are just one of several tantalising palimpsests of the medieval act of reading, many of which suggest that the experience could have been a quite different one from our own. Letters and other correspondence are recurrently described in the Middle Ages as being read out loud by messengers to whoever was present, rather than being absorbed alone by their addressee. And the debate as to whether most everyday reading happened silently in a person’s head or was actually vocalised audibly as they made their way through a book is still a live one. But more than anything, these surviving manicules affirm just how tactile an operation medieval reading could be. With readers trawling across lines of text with their fingers and thumbing back the corners of pages to turn them, some parchment books have become almost blackened through repeated handling, so much so that modern conservators’ machines, known as densitometers, can be used to measure the comparative scruffiness of pages and isolate the most dirty – and therefore likely most popular – passages of a particular text, the ones to which a certain owner turned time and time again. Not that readers went unwarned against such tough treatment of these expensive objects. Florentius de Valeranica, a tenth-century Spanish scribe, reminded his readers of the pain and difficulty of writing:

si uelis scire singulatim nuntio tibi quam grabe est scribturae pondus. oculis caliginem facit. dorsum incurbat. costas et uentrem frangit. renibus dolorem inmittit et omne corpus fastidium nutrit. ideo tu lector lente folias uersa. longe a litteris digitos tene quia sicut grando fecunditatem telluris tollit sic lector inutilis scribturam et librum euertit. nam quam suauis est nauigantibus portum extremum ita et scribtori nobissimus uersus.

If you want to know how great the burden of writing is: it mists the eyes, it curves the back, it breaks the belly and the ribs, it fills the kidneys with pain, and the body with all kinds of suffering. Therefore, turn the pages slowly, reader, and keep your fingers well away from the pages, for just as a hailstorm ruins crops, so the sloppy reader destroys both the book and the writing. As a port is sweet to the sailor, so the final line is sweet to the writer.

Some readers, however, could not help themselves. Touching while reading was not just a quotidian action, the pages naturally accruing everyday grime: it could also mark moments of emotional pique. The names or accompanying images of wrong-doers or devils are found scraped and scratched at, stabbed and smudged out. Other images have been loved into oblivion, particularly holy figures, who are often rubbed away to a blank nothingness through repeated caresses. To avoid such accidental desecration of holy text, when reading from the Torah, Jews used a yad ( , literally ‘hand’), a short metallic pointer often tipped with an actual miniature sculpture of a hand to follow the text at a respectful distance.

, literally ‘hand’), a short metallic pointer often tipped with an actual miniature sculpture of a hand to follow the text at a respectful distance.

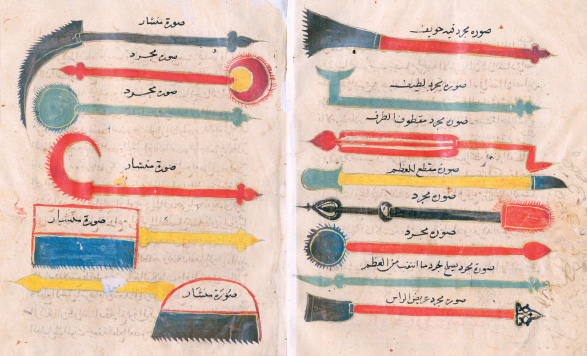

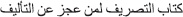

As well as scuffing and dirtying them, the fingers were also useful tools for memorising information from the pages of manuscripts. The Italian music theorist Guido of Arezzo (c.991–1033) used the hand to outline his innovative techniques for learning song. Codifying a hexacord, or six-part, system of musical notation that had developed through various Greek, Roman and early medieval iterations, Guido assigned each note within this sextupled system a name: ut, re, mi, fa, sol and la, still alive today in the modern solfège method. He then positioned each of these notes at one of nineteen points spread around the joints of the fingers. An Italian diagram of Guido’s arrangement, found in a manuscript still held at its original home in the medieval abbey of Montecassino in Italy, shows the notes spread about the hand, moving in a spiral pattern from G at the tip of the thumb, down via the notes A and B to the palm, before then moving through C, D, E and F across the base of the fingers, up the little finger repeating G, A, B, and then spiralling across the top of the fingers back into the centre. Such a system could help an individual in the complicated memorisation of particular tunes in relation to their respective scales, and it may also have allowed for teachers to sign notes at their pupils across space, correcting their notation by sight as they rehearsed new hymns.

58. A Guidonian hand from a musical miscellany made towards the end of the eleventh century in Italy.

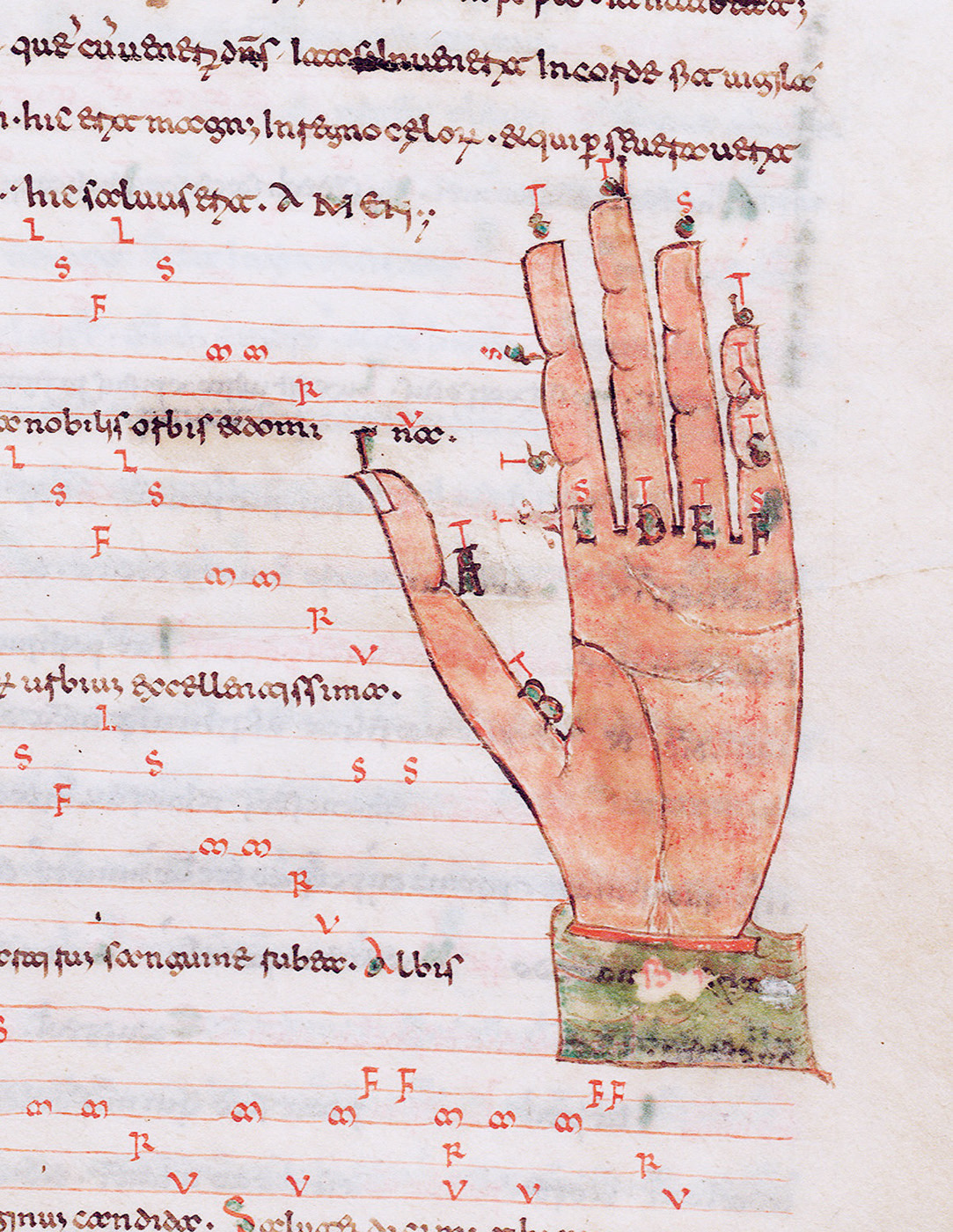

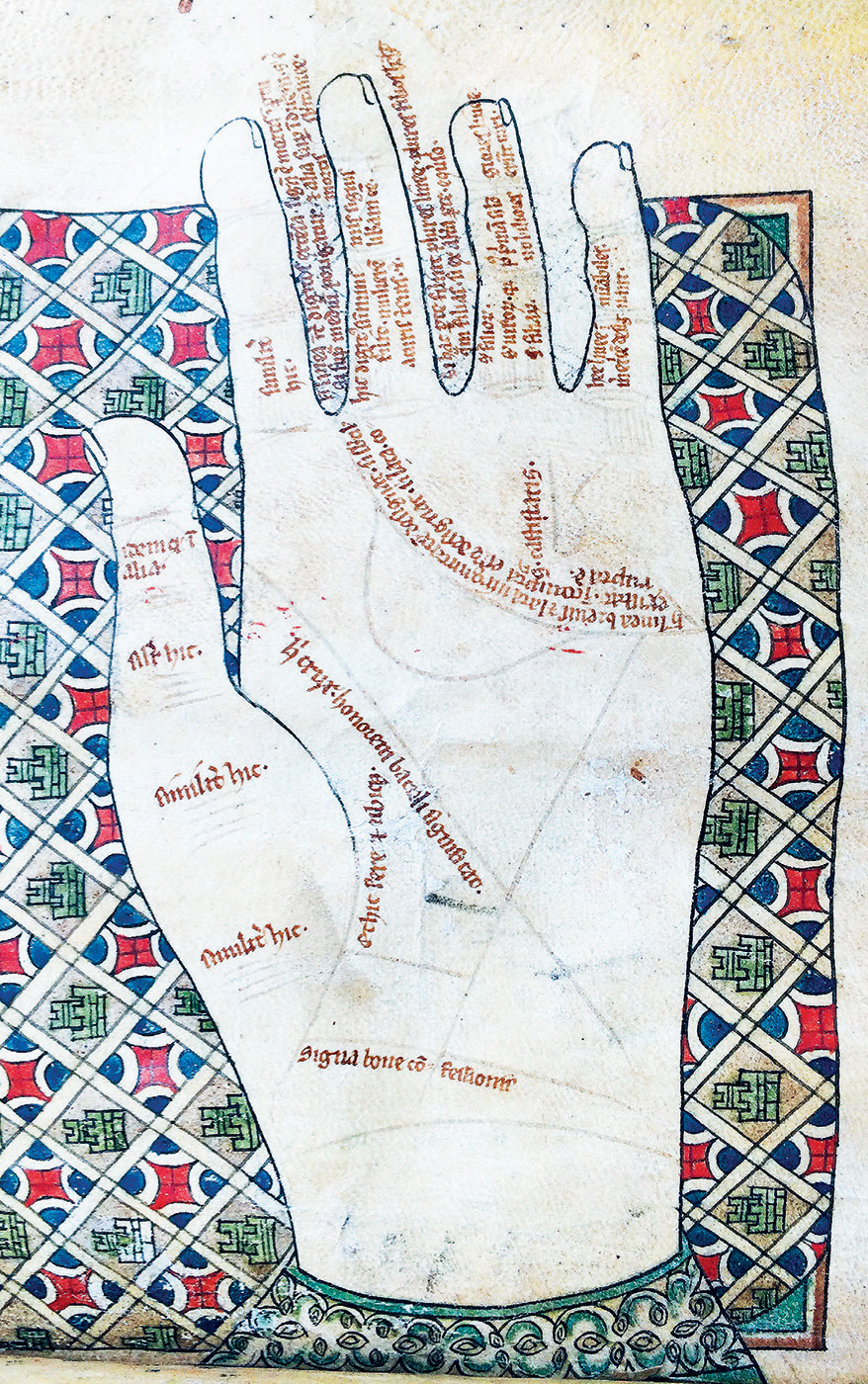

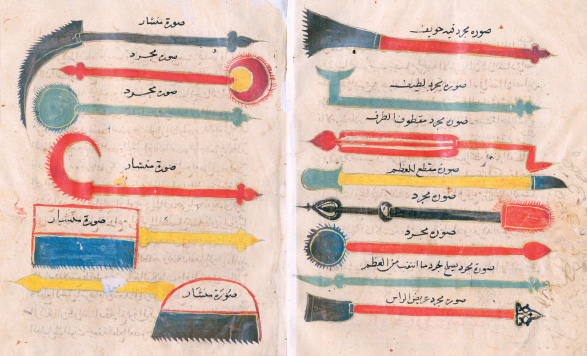

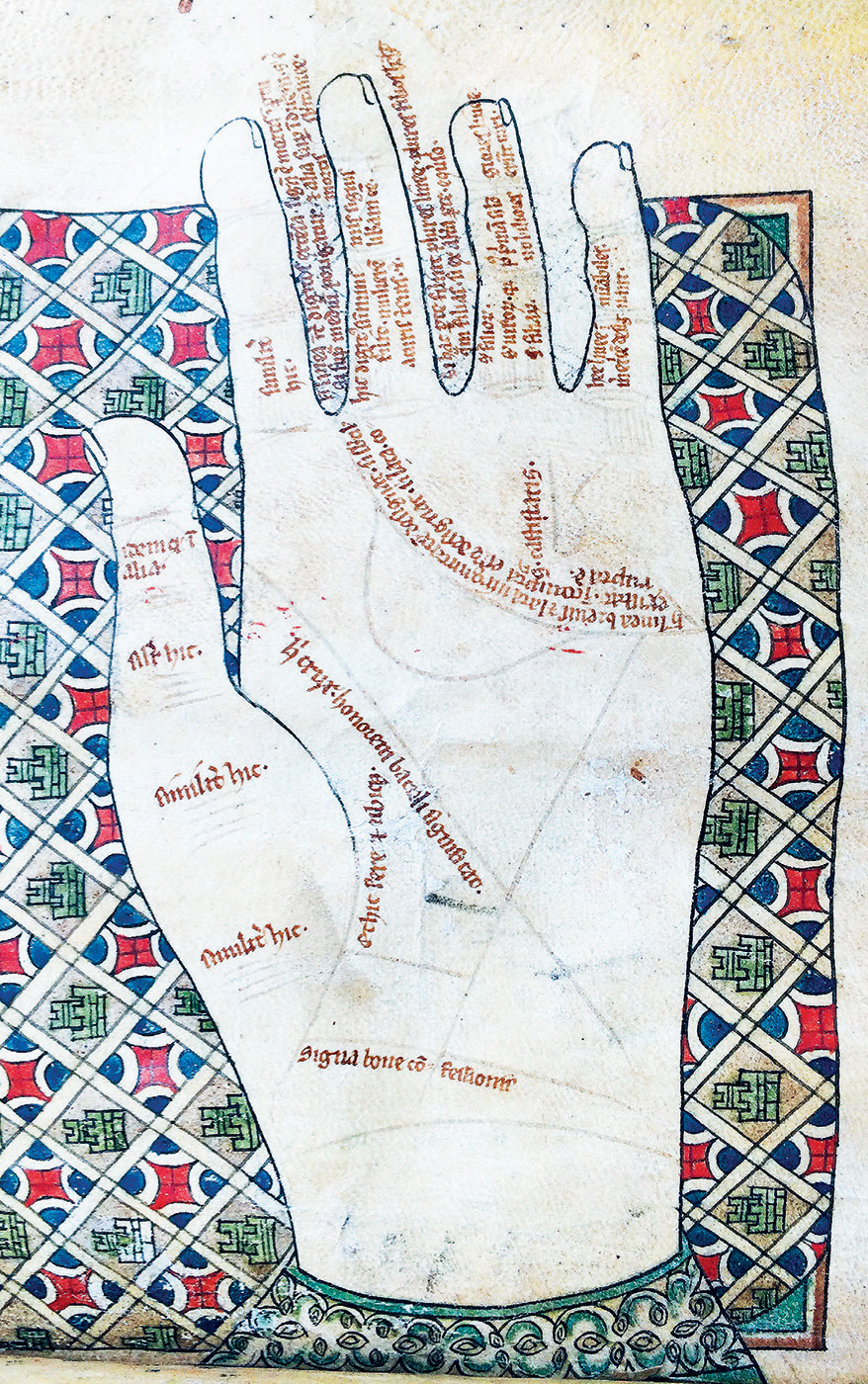

If Guidonian hands helped singers retrieve a past tune or chant from their memory or to notate it in the present, similar hands were also used to intuit future events. Chiromancy, the act of divining things to come from someone’s hands, was a prominent magical practice in the ancient world and was adopted in the medieval West through translations of detailed Arabic sources, much the same route as many important medical texts. Unlike works on health, however, which advocated understanding broad humoral dispositions and the spread of diseases across the body, chiromancers drew attention only to the minutiae, tiny differences in the lines and markings on different parts of the palm and fingers. One thirteenth-century English manuscript illustrates a magical hand covered all over with text to help find the primary points of a chiromantic reading. At the palm the three main lines or creases which form something of a triangle at the centre of the hand could be read for indications of life and death, whether the hand’s owner would be honourable or cowardly in battle, or if they would die by water or fire. The propensity of small mounds of flesh elsewhere on the joints of the fingers intimated that the person would have multiple children and escape illness with ease. And the length of fingers or the curved appearance of nails could be clues as to a number of other characteristics, from a susceptibility to leg wounds and a budding intelligence to copious income and a murderous temperament.

A whole system of elaborate miniature signs flourished across these hands. The appearance of cross shapes at the base of the fingers spelled unexpected doom. A symbol like a crossed-out letter  prognosticated that a man would rise to become a bishop, while a doubled ‘oo’ sign suggested an imminent loss of testicles for the bearer or their younger brother. How seriously medieval people took these supposed divinations was surely, as today, a matter of great variation. Some sources describe the practice simply as a silly game and misleading witchcraft, but the inclusion of palmistry points that evaluated the honour of one’s advisers or the faithfulness and virginity of a future wife hint that the readings could carry with them a degree of seriousness, should they be so interpreted. If inclined to look more closely, men and women would see that at the end of their arms they were carrying around tools for reading, singing and even a road map for their entire life to come plotted out on their own bodies.

prognosticated that a man would rise to become a bishop, while a doubled ‘oo’ sign suggested an imminent loss of testicles for the bearer or their younger brother. How seriously medieval people took these supposed divinations was surely, as today, a matter of great variation. Some sources describe the practice simply as a silly game and misleading witchcraft, but the inclusion of palmistry points that evaluated the honour of one’s advisers or the faithfulness and virginity of a future wife hint that the readings could carry with them a degree of seriousness, should they be so interpreted. If inclined to look more closely, men and women would see that at the end of their arms they were carrying around tools for reading, singing and even a road map for their entire life to come plotted out on their own bodies.

59. A hand inscribed with chiromantic readings, from a medical miscellany made in England in the 1290s.

Signing and Clasping

Although Guidonian singing spirals or chiromancy diagrams are valuable to us because they preserve intricate medieval systems of thought, the existence of such frameworks is bittersweet. For they remind us that there must have been countless social customs of signs and symbols once alive in the Middle Ages, entire sophisticated gestural dialects that have since completely vanished.

Some of these lost affectations are opaquely hinted at through fragments of written description. The influential Northumbrian author Bede (c.673–735), for instance, wrote in the 720s of a sophisticated method of numerating digits on the fingers which allowed different combinations of folding, closing and bending of two hands to sign individual numbers all the way from 0 to 9,999. We can imagine craftsmen or traders gesturing prices in this way across busy markets, or sailors signalling at sea across the deck. And it is not surprising either that Bede, a monk, was aware of such arrangements. Given the strict regulations placed on speech in some monastic settings, systems of gesture were integral to the smooth running of a religious institution like a monastery. Take the tenth-century monks of the Abbey of Cluny, an influential foundation in eastern France from which the hotel of Alexandre du Sommerard, later the Musée de Cluny, took its name. These men put particular weight on the self-abnegation of religious life, advocating a new and focused form of monasticism which preferenced prayer over much other normal human behaviour. Fasting, celibacy and extremely long periods of sung devotion characterised this French tradition, as did a strictly maintained silence thereafter. Not speaking was designed to avoid sins of the tongue, as well as to channel the monks’ prayers more thoroughly in imitation of the angels, who were thought by the Cluniacs only to sing. This was easier said than done, however. Cooking, writing, tending the land, these were all things that could not stop simply because a foundation’s inhabitants refused to engage in the un-angelic act of conversation. Almost as soon as the silent practice took root, a process of signalling sprang up that helped the monks go about the necessities of daily life. How this monastic finger-chatter might have worked in reality is hard to re-piece, but a rare sign lexicon preserved in a handful of contemporary manuscripts describes around 118 symbols for places, people and things that monks would have needed to know. Among others, we learn that:

For the sign of a dish of vegetables, drag one finger over another finger, like someone cutting vegetables that he is about to cook.

For the sign of a squid, divide all of the fingers from each other and then move them together, because squid are made up of many parts.

For the sign of a needle, strike your fists together, because this signifies metal, and after that pretend that you are holding a piece of threat in one hand and a needle in the other and that you want to send the thread through the eye of a needle.

For the sign of the Holy Virgin, draw your finger along the forehead from eyebrow to eyebrow, because that is the sign for a woman.

For the sign of something good, whatever it is that you say is good, place your thumb on one side of your jaw and your other fingers on the other side and then draw them down gently to the end of the chin.

For the sign of something bad, place your fingers spread out on your face and pretend that it is the claw of a bird grasping and tearing at something.

The more of this kind of distant descriptive evidence we discover, the more we see that gesticulations and hand gestures were a fundamental aspect of medieval religious life, even for those not part of communities vowed to perpetual silence. Islamic scholars of the period discuss the clarity that moving the hands could bring to the words of clerics when preaching, and during the observance of the Christian Mass priests were taught to raise their arms high and apart in a gesture that deliberately echoed the arms of Christ, stretched wide at the crucifixion. Folding one’s hands closed in front of one’s chest was an equally respected and potent movement in many religious settings, designed to accompany thoughts and prayers, and to encourage the faithful to at once rend their souls and embrace God close to their hearts.

Such symbols surface, too, in objects of popular religious culture. Touching a reliquary was a sure-fire way to mark one’s presence at a shrine, as well as to physically absorb the spiritual and bodily benefits of a relic’s immediate presence. But reliquaries could, in a sense, touch back. Some were formed not just as elaborately decorated boxes but in the shape of fully realised forearms, complete with hands frozen in signs of benediction. This is not necessarily because they contained within them a piece of sacred finger or arm, humerus or ulna. They could hold any holy remnant. Instead, it was their gestural potential that was prized, allowing them to be waved over the congregation as if they were the actual blessing hand of the saint themselves, spreading the holiness contained in the object’s core across banks of the assembled faithful. Hand gestures could bind secular communities together in much the same way. In the legal world the raising of both hands or resting them on holy scripture to testify was, as in some courtrooms today, of equal importance to any verbal authentication that could be offered when giving testimony. Marriage contracts also hinged on the ‘handfasting’ of a couple, their betrothal signified by the clasping of their hands together. So popular was this gesture as a symbol of love that pairs of conjoined hands, just like hearts, became a popular feature of amorous tokens, keepsakes and rings. A late medieval brooch excavated in 2006 in the grounds of St Oswald’s Church in Winwick, Cheshire, is so well preserved that we can make out a pair of cuffed hands grasping each other in the piece’s circular swoop. Engraved with small flowers on its back – perhaps, poignantly, forget-me-nots – the brooch’s intention is made clear by an inscription on its front in Anglicised French, running around its rim as if along the lovers’ sleeves: pensez de moy, ‘think of me’.

60. The Winwick Brooch, a tiny fifteenth-century gold love token in the shape of a circular pin with a pair of clasping hands.

Touch also played a role in less amorous ceremonies of fealty. A person might swear allegiance to their king or caliph by intoning an oath of obedience, but this was only officially cemented in the conjoining of hands between the two parties. Gestures of this sort seem to have played a particularly prominent part in many royal customs, continuing into the Middle Ages from earlier classical traditions. As God’s representatives on earth, rulers went through elaborate ceremonies that involved both being touched and touching others. A third-century sculpted relief at Naqsh-e Rostam ( ), a necropolis near the ancient city of Persepolis in Iran, shows an enormous image of the Sasanian King Ardashir I grasping a symbolic ring of rule handed to him by the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda. Later Arabian investitures of the Mamluk sultans and Abbasid caliphs would see the ruler hold or be girded with a curved, Bedouin-style sword. European monarchs too were anointed on the forehead with holy oil by archbishops or other senior clergymen during their coronations, recalling the biblical model of the much-revered warrior-king David by the prophet Samuel in the Old Testament. And by the later Middle Ages the touch of a monarch themselves, especially immediately after such coronation rites, had reciprocally transformed into a much-prized thing. So charismatic was this touch that in certain cases it was even thought to have the ability to heal various illnesses through royal caress. Scrofula, a form of tuberculosis of the lymph glands causing large sores and swellings around the neck, was a disease that became so associated with this type of monarchical healing that it took the Latin name morbus regius, the ‘regal disease’ or, sometimes, the ‘king’s evil’. From the eleventh century onwards its French and English victims were granted special audiences with their respective monarchs to receive this miraculous cure. Records are hazy as to how precisely such healing touches were given: some royals may have employed a lingering stroke of the face and neck, while others may have made do with a simple pat on the head. Either way, the hands of the king carried an intense power to cleanse severe sickness.

), a necropolis near the ancient city of Persepolis in Iran, shows an enormous image of the Sasanian King Ardashir I grasping a symbolic ring of rule handed to him by the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda. Later Arabian investitures of the Mamluk sultans and Abbasid caliphs would see the ruler hold or be girded with a curved, Bedouin-style sword. European monarchs too were anointed on the forehead with holy oil by archbishops or other senior clergymen during their coronations, recalling the biblical model of the much-revered warrior-king David by the prophet Samuel in the Old Testament. And by the later Middle Ages the touch of a monarch themselves, especially immediately after such coronation rites, had reciprocally transformed into a much-prized thing. So charismatic was this touch that in certain cases it was even thought to have the ability to heal various illnesses through royal caress. Scrofula, a form of tuberculosis of the lymph glands causing large sores and swellings around the neck, was a disease that became so associated with this type of monarchical healing that it took the Latin name morbus regius, the ‘regal disease’ or, sometimes, the ‘king’s evil’. From the eleventh century onwards its French and English victims were granted special audiences with their respective monarchs to receive this miraculous cure. Records are hazy as to how precisely such healing touches were given: some royals may have employed a lingering stroke of the face and neck, while others may have made do with a simple pat on the head. Either way, the hands of the king carried an intense power to cleanse severe sickness.

61. A third-century sculpted relief of the Sasanian King Ardashir I grasping a symbolic ring of kingship, preserved at the ancient necropolis at Naqsh-e Rostam ( ), Iran.

), Iran.

Cleaning these royal hands themselves could be even more complicated. A link between hands and health had long held strong currency in the medieval Muslim world. The Qur’anic dictum that the body should be purified before prayer gave rise to regular ritual ablutions, involving the washing of the hands, feet, face and sometimes the whole body. For some this may have been a trivial point of spiritual etiquette, but for others the washing of the hands could be a site for real creativity. In around 1206 the Arabic scholar and engineer Ismail al-Jazari (1136–1206) completed his Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices ( ), the most elaborate in a series of technical manuals stretching back to ninth-century Baghdad, which outlined how to build a range of mechanical automata, functional machines often featuring moving beasts and figures. Some illustrated copies of the Book of Knowledge accompany al-Jazari’s detailed text with colourful diagrams that bring these creations to life, labelled to correspond with his extensive notes on construction. Alongside an elephant clock, a floating four-piece musical band, an automatically locking castle gate, a model for mechanised blood-letting and many other pieces, one of these manuscripts’ folios shows a machine that alJazari was commissioned to build by his patron, the Artuqid king Salih. The King, al-Jazari writes, ‘disliked a servant or slave girl pouring water onto his hands for him to perform his ritual ablutions’. To help, the inventor created an elaborate contraption in the shape of a large canopy. When the King pulled a lever, the hydraulic power of the water stored in its hidden upper tank made a bird at the top of the device sing. Water then poured steadily into a basin from a jug supported by a hollow mechanical copper servant who also held a mirror and a comb for him to use as he washed. Another bird then drained the finished water away, before, finally, the servant automatically lowered her left hand in a finishing flourish to offer the King a towel to dry himself.

), the most elaborate in a series of technical manuals stretching back to ninth-century Baghdad, which outlined how to build a range of mechanical automata, functional machines often featuring moving beasts and figures. Some illustrated copies of the Book of Knowledge accompany al-Jazari’s detailed text with colourful diagrams that bring these creations to life, labelled to correspond with his extensive notes on construction. Alongside an elephant clock, a floating four-piece musical band, an automatically locking castle gate, a model for mechanised blood-letting and many other pieces, one of these manuscripts’ folios shows a machine that alJazari was commissioned to build by his patron, the Artuqid king Salih. The King, al-Jazari writes, ‘disliked a servant or slave girl pouring water onto his hands for him to perform his ritual ablutions’. To help, the inventor created an elaborate contraption in the shape of a large canopy. When the King pulled a lever, the hydraulic power of the water stored in its hidden upper tank made a bird at the top of the device sing. Water then poured steadily into a basin from a jug supported by a hollow mechanical copper servant who also held a mirror and a comb for him to use as he washed. Another bird then drained the finished water away, before, finally, the servant automatically lowered her left hand in a finishing flourish to offer the King a towel to dry himself.

Lavishing such meticulous attention on these sovereign hands made sense. Alongside the officiating priest giving wide-armed blessing to his congregation and the surgeon feeling his way across the body of a patient with his finger-like tools, the king was among only a few medieval individuals whose appendages were invested with the awesome power to transform. Hands in the Middle Ages let the world in. Their touch gave shape to experiences and objects, people and places, enacting everything from the playful spank in a game of Hot Cockles to the momentous binding grasp of marriage. Writing in the fifth century, Saint Augustine theorised that the hands of men and women functioned in their own right as what he called verba visibilia, ‘visible words’. Although no medieval hands survive today to speak this gestural language to us, we are lucky that it still lingers in artistic objects and the traces of customs: sealing contracts, scratching devils, teaching music or commanding life and death.

62. A folio from a version of Ismail al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices copied by the calligrapher Farruq ibn Abd al-Latif in 1315, probably in Syria. It shows a mechanical device for washing the king’s hands, complete with a singing bird and automatous servant who hands the user a towel on finishing.

), or Latin, chirurgia, both combinations of the terms for ‘hand’ and ‘work’. In early medieval Old English texts direct conflations were made of medical tools with the people who wielded them, the terms for surgeon and surgical instrument often interchangeable with one another. And in later Middle English writings too the language of the medical professional was caught up in everyday bodily terminology. The ring finger was often also dubbed the leche fingir – from the Old English for doctor, læce – both because it was commonly used to mix and apply medicines and because its veins were thought to lead directly to the heart. Henri de Mondeville, the French surgeon whose writings on skin we have already seen vividly illustrated by the figure of a flayed man, even went so far as to describe the iron joints and blades of his surgical knives as being like a surgeon’s very own fingernails and digits. This linguistic idea could also work backwards, with surgeons writing that they themselves needed to be delicately formed in the manner of their exquisite surgical tools. The Italian medic Lanfranc of Milan (c.1245–1306) stressed the importance of a surgeon’s well-shaped hands with long small fingers, while his contemporary the Flemish author Jan Yperman (c.1260–1330), spoke of surgeons needing ‘vingheren ende lanc sterc van lichame, niet bevende’, ‘fingers extending long from the body and which do not tremble’.

), or Latin, chirurgia, both combinations of the terms for ‘hand’ and ‘work’. In early medieval Old English texts direct conflations were made of medical tools with the people who wielded them, the terms for surgeon and surgical instrument often interchangeable with one another. And in later Middle English writings too the language of the medical professional was caught up in everyday bodily terminology. The ring finger was often also dubbed the leche fingir – from the Old English for doctor, læce – both because it was commonly used to mix and apply medicines and because its veins were thought to lead directly to the heart. Henri de Mondeville, the French surgeon whose writings on skin we have already seen vividly illustrated by the figure of a flayed man, even went so far as to describe the iron joints and blades of his surgical knives as being like a surgeon’s very own fingernails and digits. This linguistic idea could also work backwards, with surgeons writing that they themselves needed to be delicately formed in the manner of their exquisite surgical tools. The Italian medic Lanfranc of Milan (c.1245–1306) stressed the importance of a surgeon’s well-shaped hands with long small fingers, while his contemporary the Flemish author Jan Yperman (c.1260–1330), spoke of surgeons needing ‘vingheren ende lanc sterc van lichame, niet bevende’, ‘fingers extending long from the body and which do not tremble’. , known in English as The Method of Medicine). It preserves around 200 depictions of surgical tools, elongated forms slotted between passages of explanatory text. Like the illustrated skeleton of the Persian physician Mansur, whose bones are presented

, known in English as The Method of Medicine). It preserves around 200 depictions of surgical tools, elongated forms slotted between passages of explanatory text. Like the illustrated skeleton of the Persian physician Mansur, whose bones are presented

, literally ‘hand’), a short metallic pointer often tipped with an actual miniature sculpture of a hand to follow the text at a respectful distance.

, literally ‘hand’), a short metallic pointer often tipped with an actual miniature sculpture of a hand to follow the text at a respectful distance.

prognosticated that a man would rise to become a bishop, while a doubled ‘oo’ sign suggested an imminent loss of testicles for the bearer or their younger brother. How seriously medieval people took these supposed divinations was surely, as today, a matter of great variation. Some sources describe the practice simply as a silly game and misleading witchcraft, but the inclusion of palmistry points that evaluated the honour of one’s advisers or the faithfulness and virginity of a future wife hint that the readings could carry with them a degree of seriousness, should they

prognosticated that a man would rise to become a bishop, while a doubled ‘oo’ sign suggested an imminent loss of testicles for the bearer or their younger brother. How seriously medieval people took these supposed divinations was surely, as today, a matter of great variation. Some sources describe the practice simply as a silly game and misleading witchcraft, but the inclusion of palmistry points that evaluated the honour of one’s advisers or the faithfulness and virginity of a future wife hint that the readings could carry with them a degree of seriousness, should they

), a necropolis near the ancient city of Persepolis in Iran, shows an enormous image of the Sasanian King Ardashir I grasping a symbolic ring of rule handed to him by the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda. Later Arabian investitures of the Mamluk sultans and Abbasid caliphs would see the ruler hold or be girded with a curved, Bedouin-style sword. European monarchs too were anointed on the forehead with holy oil by archbishops or other senior clergymen during their

), a necropolis near the ancient city of Persepolis in Iran, shows an enormous image of the Sasanian King Ardashir I grasping a symbolic ring of rule handed to him by the Zoroastrian god, Ahura Mazda. Later Arabian investitures of the Mamluk sultans and Abbasid caliphs would see the ruler hold or be girded with a curved, Bedouin-style sword. European monarchs too were anointed on the forehead with holy oil by archbishops or other senior clergymen during their

), Iran.

), Iran. ), the most elaborate in a series of technical manuals stretching back to ninth-century Baghdad, which outlined how to build a range of mechanical automata, functional machines often featuring moving beasts and figures. Some illustrated copies of the Book of Knowledge accompany al-Jazari’s detailed text with colourful diagrams that bring these creations to life, labelled to correspond with his extensive notes on construction. Alongside an elephant clock, a floating four-piece musical band, an automatically locking castle gate, a model for mechanised blood-letting and many other pieces, one of these manuscripts’ folios shows a machine that alJazari was commissioned to build by his patron, the Artuqid king Salih. The King, al-Jazari writes, ‘disliked a servant or slave girl pouring water onto his hands for him to perform his ritual ablutions’. To help, the inventor created an elaborate contraption in the shape of a large canopy. When the King pulled a lever, the hydraulic power of the water stored in its hidden upper tank made a bird at the top of the device sing. Water then poured steadily into a basin from a jug supported by a hollow mechanical copper servant who also held a mirror and a comb for him to use as he washed. Another bird then drained the finished water away, before, finally, the servant automatically lowered her left hand in a finishing flourish to offer the King a towel to dry himself.

), the most elaborate in a series of technical manuals stretching back to ninth-century Baghdad, which outlined how to build a range of mechanical automata, functional machines often featuring moving beasts and figures. Some illustrated copies of the Book of Knowledge accompany al-Jazari’s detailed text with colourful diagrams that bring these creations to life, labelled to correspond with his extensive notes on construction. Alongside an elephant clock, a floating four-piece musical band, an automatically locking castle gate, a model for mechanised blood-letting and many other pieces, one of these manuscripts’ folios shows a machine that alJazari was commissioned to build by his patron, the Artuqid king Salih. The King, al-Jazari writes, ‘disliked a servant or slave girl pouring water onto his hands for him to perform his ritual ablutions’. To help, the inventor created an elaborate contraption in the shape of a large canopy. When the King pulled a lever, the hydraulic power of the water stored in its hidden upper tank made a bird at the top of the device sing. Water then poured steadily into a basin from a jug supported by a hollow mechanical copper servant who also held a mirror and a comb for him to use as he washed. Another bird then drained the finished water away, before, finally, the servant automatically lowered her left hand in a finishing flourish to offer the King a towel to dry himself.