On the surface this sculpture of the Virgin and Child seems no more remarkable than any other small-scale object to survive from the Middle Ages. Mary’s pose is tranquil and iconic, staring impassively into the distance with her painted grey-blue eyes as she feeds the infant Christ. If anything, it is a rather static portrayal of a deeply symbolic maternal embrace. The small child feels almost like an afterthought, welded to her left arm beside a rather awkwardly positioned breast. The piece is also not in the best condition. Despite the odd moment of subtle shading that still lingers around Mary’s rosy red cheeks, the sculpture’s paint and gold have in many places fallen away. Once vivid details like the crown on the Virgin’s head or her outstretched right hand have been snapped off, reduced to brownish stumps, exposing the grain of the untreated wood beneath.

There is, though, something more interesting afoot. A thick line ruptures the scene, a black gap running from the bottom of Mary’s neck straight down her chest, right to the bottom of her skirt. Unusua lly, a series of small hinges subtly concealed within the side panels of her throne allow the sculpture’s front to be thrown open in two, revealing a more opulent world within. Like a medieval matryoshka doll, the Virgin’s previous picture of still calm in fact contains a complex visual scheme. Her body is the busy stage for multiple animated figures, including a central carving of God the Father and painted scenes from the lives of both Christ and Mary on its newly formed wings. With the flip of a hand the sculpture’s skeleton bisects to expose a set of unexpected holy interiors.

This type of opening figurine from the Middle Ages is known as a Shrine Madonna. Few of these novel sculptures survive today, but we can tell from the visual splendour and elaborate detailing of those which do that they were important objects for the communities who commissioned them. First and foremost, they were tools for individual and communal prayer, acting as anthropomorphic altarpieces around which people could gather. Accounts of one religious foundation in northern France record an even larger, life-size Shrine Madonna, sadly now lost, which was placed on the high altar of its church to form the primary focus of daily devotions. A nun from this same community, one Sister Candide, noted in her diary that the sculpture would be opened up during times of crisis, especially in moments of drought, when the revelation of the Madonna’s internal panoply of scenes was thought to amplify the pleas of the faithful and bring rain to feed their crops. Such an opening was a truly wondrous event for people like Candide. As she wrote:

Quand’elle estoit ainsi ouverte, ce n’estoit une Vierge, mais un monde et plus qu’un monde … petits mondes enfermez dans le corps de cette monstrueuse figure.

When she was open she was not a Virgin but a world and more than a world … little worlds enclosed inside the body of this monstrous figure.

This image of Mary as a series of self-contained worlds was a common refrain of theologians. In extolling the virtues of the Virgin Birth they often turned to elaborate metaphors of enclosure when describing the holy womb. It was a saintly oven in which Christ had been incubated, a treasured ark protecting precious cargo or a doorway through which Christ entered the world. By hinging apart the wings of the Shrine Madonna, its communities were daily re-enacting a fundamental moment of Christian salvation, opening the Virgin’s heavenly body to see Christ, their saviour, growing inside at the miraculous behest of God.

Mary was, of course, unique in conceiving through such complex heavenly means. Yet even ordinary medieval pregnancies were still thought to follow a highly complicated anatomical process. Competing and sometimes clashing notions of birth were put forward by different medical authorities, but they all agreed that the womb formed a central part of a larger sexual system working within a woman’s body. This included the cervix, vagina, ovaries and clitoris, although the last of these was an organ seldom mentioned in medieval accounts. Following classical thinkers, the male and female sex organs were presented as something of a mirror to one another, each inverted versions of similar genitals that on the surface suggested a certain similarity between the sexes, at least in terminology: the ovaries were discussed as a pair of female testicles and their emissions were seen as equally vital to conception as the male sperm. But for virtually all medical authorities, inevitably themselves men, this mirroring also served to emphasise the difference between the conspicuously external nature of the penis and testes and what they saw as the vacant interiority of the vagina and uterus, masculine presence contrasted with feminine absence. Of the two types, it was still the female body that received by some distance the greater attention in such theorising, made so intriguing to this male audience through its ability to menstruate and bear children. Even so, their writings all still espoused distinctly male-oriented notions of reproduction, where women served as a receptacle for an all-singing-all-dancing masculine seed.

The specifics of this union were relatively well plotted out. The ancients had conceived that male ejaculate was the product of the brain via the spinal column, but by medieval times most theorists recognised this to be the role of the testicles, their winding veins thought to form spermatic substance from the concoction or cooking of blood. During sex this male sperm made its way via the vagina to the womb, where it combined with female sperm that had been released from the ovaries and drawn to the uterus through two thin cords. The two sperms together formed a mass, which through the womb’s actions of heat and compression slowly solidified into the beginnings of an embryo. Some leftover transmuted essence conjoined to the uterus to become the placenta, a network of veins and arteries whose ligaments suspended the foetus and nourished it with vital spirits drawn from the mother. This child first developed a liver to create its own blood flow and was then imbued with a soul, specified by medieval churchmen as happening after forty days for a male and eighty days for a female. Once the baby was born, growth continued through the nourishment of its mother’s milk, a substance thought to be concocted in the breast from the same maternal blood that had once fed the foetus in utero.

Contemporary medical authors were quick to explain the entire process of conception in terms of metaphor, although they were rather less imaginative than theologians describing the Virgin Birth. The thirteenth-century Italian author Giles of Rome chose a rather unceremonious workaday comparison, writing that the sperm might be seen as a carpenter acting on the wood of menstrual blood to create a foetus. In his Canon of Medicine Ibn Sina wrote even less romantically that generation might be compared to the manufacture of cheese, with the clotting agent of the male sperm acting on the milk of the female sperm to coagulate together into a child. More eloquent, perhaps, is the interior of the sculpted Shrine Madonna, which also conveys something of the contemporary understanding of female anatomy. Its internal system is split into seven sections which appear to echo the common medieval description of the uterus as divided internally into seven cells, each of which could nurture a child. A foetus generated in three of these cells would birth a boy, three more would birth a girl, and a single final cell would birth a hermaphroditic child. Subtly mirroring a real body within its sculpted wooden forms, this Shrine Madonna co-opted the detail of contemporary gynaecological medicine to signal just how exceptional the birth of Christ had been: Mary had supposedly circumvented this entire complex sexual system with nothing more than the miraculous words of an angel.

Written into these medieval concepts of sexual medicine was an unapologetic imbalance between the genders that was to have dramatic impact on both the nature and quality of women’s lives throughout the Middle Ages and beyond. On a fundamental level, the female body was believed to be biologically subordinate to the male. This was in part due to a basic humoral distinction between the sexes. It was men who formed the true ideal for mankind, especially in terms of the much-vaunted bodily heat at the heart of anatomical understanding. Men’s bodies were thought to produce this vital nourishing warmth with ease and in abundance, meaning that they grew larger and produced more hair, as well as having no trouble dispersing any humoral excesses naturally built up within the hot body through the production of sperm or sweat. Women, on the other hand, inhabited bodies that were far colder, and in some cases were even described as closer in type to the bodies of children than those of fiery, fully grown males. Following this logic, female growth was inevitably slower and they were on the whole thought to be smaller and smoother, tending towards physical weakness and a sedentary fragility. For these inferior bodies, too frigid to evacuate the humours through sweat or concoction, the only option for purging accumulated excess was menstruation.

It was to this unique function of women’s bodies that the male medical academy repeatedly returned in order to decipher both women’s physiology and their psyche. The texture, colour and frequency of a woman’s menstrual blood might all be used to make various judgements as to her constitution, casting her as either careful or irrational, hardy or contrarian. As with any other manifestations of humoral effects on the body – hair colour, skin colour, the size and shape of the nose or forehead or chin or ears – medical frameworks were set up to suggest that these details revealed certain inner truths of character or temperament. And the divining of mentality or morality from blood flow was so ingrained and apparently logical that it was even espoused by female authors themselves, when given the rare opportunity to write about their own bodies. In her twelfth-century treatise Causae et curae, ‘Causes and Cures’, Hildegard of Bingen outlined four general types into which the various constitutions of men and women fell. Men are arranged by her in order of vitality, fertility and character, from a hardy ideal with reddish skin and fiery blood through to more vapid and infertile types with weak veins and a pale complexion. Her four types of women, by contrast, are defined by their menstrual flow. A large woman with heavy, reddish menses would prove prudent and chaste, a woman with a heavy flow of bluer blood tended towards inconsistency and would be happier without a husband, while other types with different patterns of menstruation might have either a good memory or an inactive, sluggish mind.

It is hardly comforting that these formal medical stereotypes were consistent with biological ideas about the humours, but there was at least some internal logic to them. In other areas, however, little need was felt for such deduction, and thinkers brandished these accepted humoral inferiorities and patterns of menstruation as a blunt tool for an unbridled and blatant misogyny. Catholic theology, for instance, viewed childbirth as womankind’s share of the punishment for Original Sin, and religious discourses equating blood with uncleanliness in both Judaism and Islam also provided complicated superstitious grounds for the demonisation of menstruating women. Among other ideas, even supposedly learned treatises circulated the notion that menstrual blood could turn bronze objects black, perish crops or drive animals mad, and that menstruating women might be able to transmit their problematic feminine temperaments onto innocent men through an evil, witch-like, sideways glance. One thirteenth-century Latin text, De secretis mulierum, ‘On the Secrets of Women’ – originally a manual for teaching clergy about reproduction but soon popularised as a foundational philo sophical argument for medieval and early modern misogyny – even suggested that one could:

Capiantur capilli mulieres menstruosae et ponantur sub terra pingui ubi iacuit simus tempore hyemali tunc in vere sive aestate quando calescent calore solis generabitur serpens longus et fortis

Take the hairs of a menstruating woman and place them in the fertile earth under manure during the winter, then in spring or summer when they are heated by the sun, a long, stout serpent will be generated.

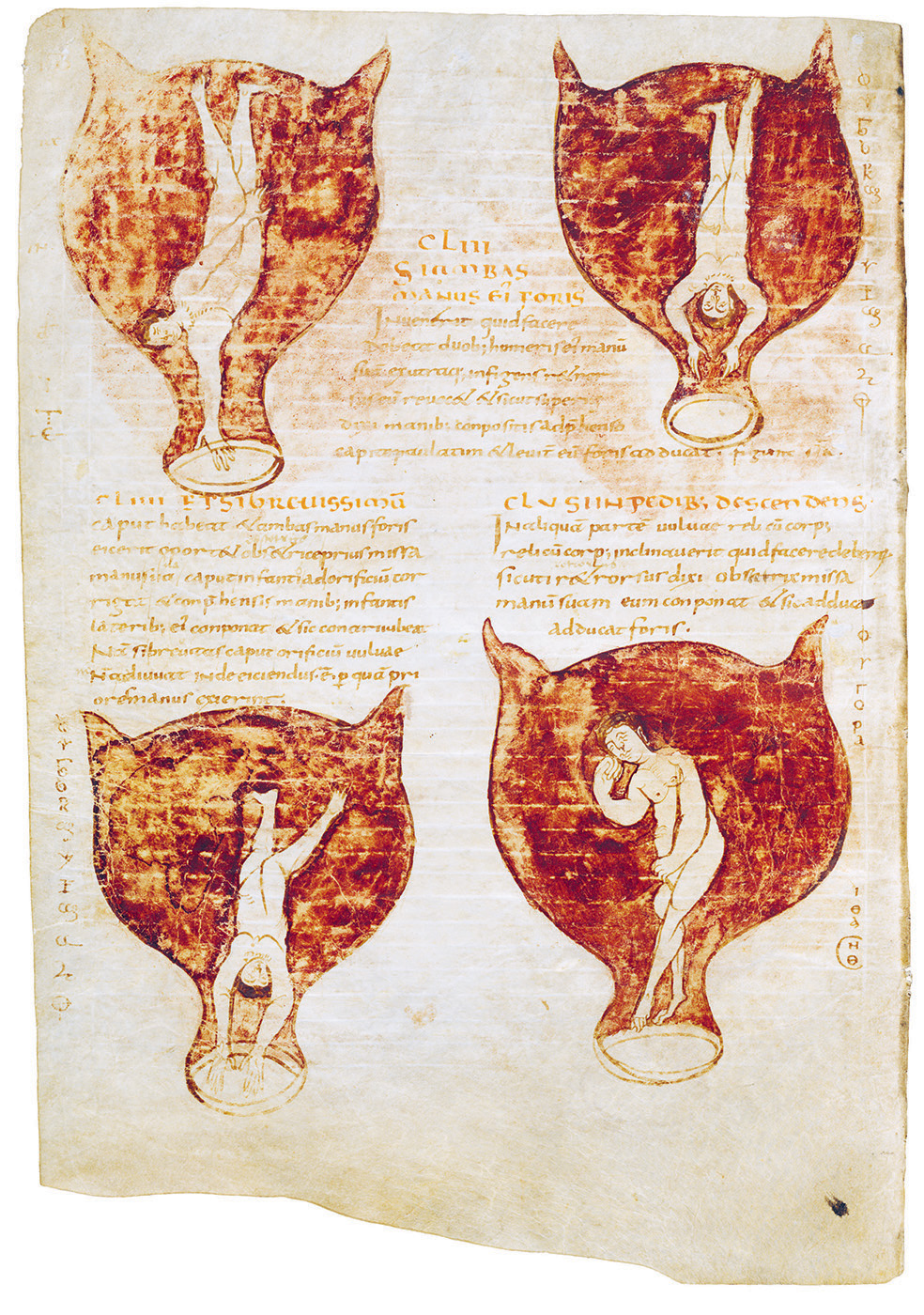

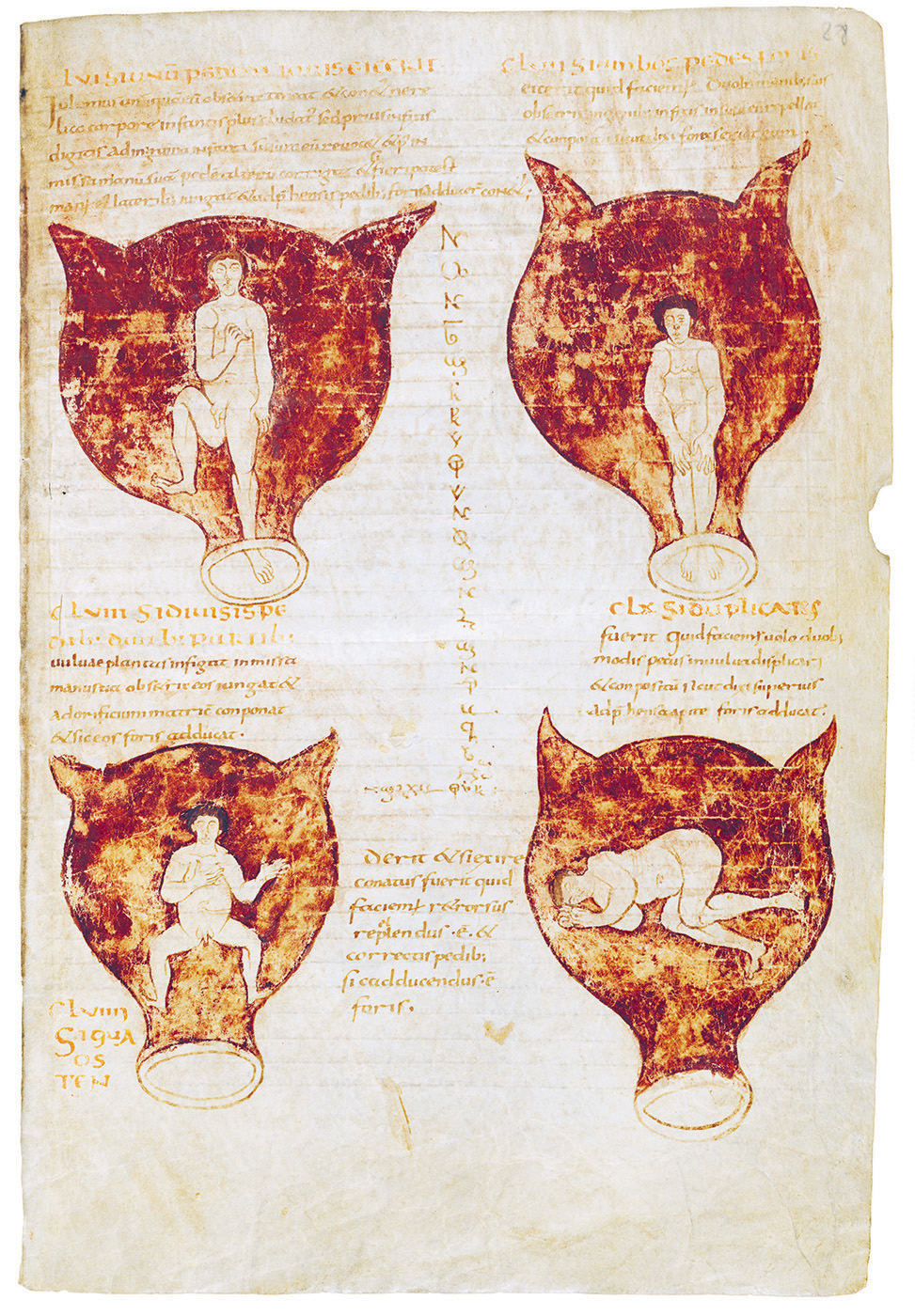

Another clear sign of these male thinkers’ fascination with menstruation and birth is that many more medieval images of wombs survive than of penises. Most that do occur feature as part of a longstanding illustrative tradition accompanying treatises on gynaecology and obstetrics, especially an influential text known as the Gynaikeia. Based on the first- or second-century texts of the Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus, the treatise was known in Europe through a Latin translation made three or four centuries later by an author known only as Muscio, a writer perhaps from north Africa about whom we know little. Copies of this text can depict up to seventeen presentations of unborn foetuses in the womb alongside instructions as to their best methods of delivery. In pictures like this a tiny, perfectly proportioned figure symbolises the unborn foetus, normally floating within a stylised circular outline representing the womb. The earliest-known such series is found in a ninth-century manuscript in the Royal Library in Brussels, where foetuses are shown in a variety of combinations and positions: twins, triplets, quadruplets, more complicated breach and compound births, and even a monstrous womb containing eleven children. Throughout, the organ is clearly rendered with a circular funnelled opening to the bottom and two horns to the top, presumably intimating the direction of the ovaries, the whole affair rendered with a light red, semi-transparent wash as if it were blown from fragile glass.

71. Eight presentations of the foetus in the womb, from a ninth-century gynaecological manuscript.

Like other luxurious illustrated medical books – lavish herbals or surgical manuals – it is doubtful that expensive tomes such as this would actually have been used by medieval healers, at least not in the sense that they were casually browsed for solutions at the bedside of a woman going into labour. Leaving aside the unhelpful distortions of its diagrammatic images, the strips of text offer only cursory advice to the practitioner in short phrases: Si ambos pedes foris eiecerit (‘If both of the feet are extending out’), Si genua ostenderit (‘If the knees present first’), Si plures ab uno fuerint (‘If there is more than one child’) and so on. Other texts, though, offered more directly helpful guidance, advising that women close to birth be bathed often, their bellies anointed with various oils, and that they eat only easily digestible foods. Some followed humoral logic to suggest a more specific diet in the lead-up to the birth. Michele Savonarola (c.1385–1468), an Italian humanist and physician, wrote in his De regimine pregnantium, ‘On the Regimen of Pregnant Women’, that the patient should avoid fried fish and cold water, sticking instead to bran bread, fruit and (worryingly, from a modern perspective) red wine. As was common elsewhere in healing, theoretically sound academic treatments intermingled in gynaecological treatises with far more folkloric medicines, especially when it came to advice for women who did not wish to get pregnant in the first place. Contraceptives tended towards the superstitious, like these four examples included in the Salernitan text the Trotula:

If a woman does not wish to conceive, let her carry against her nude flesh the womb of a goat which has never had offspring.

Or there is found a certain stone, named gagates, which if it is held by the woman or even tasted prohibits conception.

Otherwise, take a male weasel and let its testicles be removed and let it be released alive. Let the woman carry these testicles with her in her bosom and let her tie them in goose skin or in another skin, and she will not conceive.

If she has been badly torn in birth and afterward for fear of death does not wish to conceive any more, let her put into the after-birth as many grains of caper spurge or barley as the number of years she wishes to remain barren. And if she wishes to remain barren for ever, let her put in a handful.

The Trotula also offers advice on dealing with the uterus. A highly sensitive organ, if it was not regularly purged through either sex or menstruation then most medical authorities agreed with ancient theorists like Hippocrates that it might either begin to give off deadly fumes or could itself rise up within the body towards the chest and head. This condition, known as uterine suffocation, was thought to cause the patient to swoon or faint, feel choked by the fumes, swell in the neck and throat, and in extreme cases even die. It was up to practitioners to attempt to wrangle the womb back to its original position. More pragmatic healers turned to practical medicines, including making foul smells under the nose by burning feathers, wool and linen in order to drive the womb from the head, or correspondingly sweet-smelling spices and herbs to suffumigate the vagina, tempting the womb back downwards to its correct position. Healers also turned to more superstitious means to address the malady, which some believed to be caused by demonic possession. Charms were designed to be intoned over the sick woman as a form of exorcism, like this tenth-century example, now in Switzerland, addressed to help a maid known only by the initial N:

To the pain in the womb … O womb womb womb, cylindrical womb, red womb, white womb, fleshy womb, bleeding womb, large womb, nervous womb, floated womb, O demoniacal one! …

In the name of God the Father … Stop the womb of Thy maid N. and heal its affliction, for it is moving violently … I conjure thee, O womb, by our Lord Jesus Christ … not to occupy her head, throat, neck, chest, ears, teeth, eyes, nostrils, shoulder blades, arms, hands, heart, stomach, spleen, kidneys, back, sides, joints, navel, intestines, bladder, thighs, shins, heels nails, but to lie down quietly in the place which God chose for thee, so that this maid of God, N., be restored to health.

That we might find such theories nonsense today is fair, although a formal diagnosis of ‘hysteria’ – a uniquely feminine illness deriving from the term hystera ( ), the word used for ‘uterus’ in the very same ancient Greek medicine that spawned the wandering womb – was only excised from some modern professional psychiatric guidelines as late as the 1950s.

), the word used for ‘uterus’ in the very same ancient Greek medicine that spawned the wandering womb – was only excised from some modern professional psychiatric guidelines as late as the 1950s.

For guidance in understanding these wildly diverse layers of medieval advice on birth, some pregnant women would have turned to a midwife. This is a complicated group of practitioners to pin down, not least because beyond the sparse collections of academic treatises and magical fragments the act of birth was rarely documented in detail in a formal sense. At the beginning of the period the number of professional midwives seems to have declined significantly from their once prominent position in the late Roman world, where they would have attended pregnant women and helped with delivery, inspecting the genitals and offering massage to the stomach or advice on breathing. By the early Middle Ages we get only a fleeting mention of their work in occasional legal proceedings or fictional narratives. Births at this point were mostly overseen by local healers and older female family members, whose expertise was grounded in practical experience rather than academic knowledge. But by the twelfth century midwifery as a profession appears to have been on the up once more. Islamic commentators began to write of the intense pains and difficulties of birth and mention a number of areas of obstetrical specialism, both in methods of delivery and the complicated aftercare of mother and child. And in Europe the rise in midwives was met by attempts from university doctors, the state and the Church to take increased control over the practice. For the academy, writing theoretically about women’s medicine was designed, at least in part, to bring a previously largely female profession to heel, subsuming midwives’ work within what they saw as their own superior intellectual understanding of the body. Local governments, on the other hand, were more concerned with a broader development of public health, enforcing certain legal frameworks that eventually included some sensible egalitarian measures: for example, that midwives, once licensed by local regulating bodies, should be mandated to treat the poor as well as the wealthy.

The Church’s interest in the matter was less bureaucratic. It addressed instead a serious concern for the spiritual health of the many children that did not survive birth. Accurate maternal mortality figures are difficult, if not impossible, to come by, certainly when generalising across the whole of the Mediterranean. But if, from existing records, we can estimate that around one in five medieval women died from complications either during or after birth, and also that they might have given birth to an average of five or six children, we can imagine how genuinely dangerous and fraught an experience pregnancy must have been for many. One poem, gathered in the thirteenth-century German anthology Carmina Burana, evocatively describes the whispers a pregnant woman might perceive around her as she walked down the street: ‘Cum vident hunc uterum / alter pulsat alterum, silent dum transierim’ (‘when they see this womb / they tap each other and pass by, silent’). Churchmen were clear that a midwife would be needed if these fears were ever realised, intervening to perform the medieval equivalent of a Caesarean section. In the pre-modern era these were procedures undertaken only after the death of a woman in labour, described as sectio in mortua, the ‘cutting open of the dead woman’. They were not intended to save the life of a child, rather to allow for an emergency baptism of its soul before it too passed away.

Perhaps because of this extreme danger, the successful birth of a child was something to be celebrated with real gusto. This was often marked through a variety of elaborate gifts to new mothers, a host of hopeful objects wishing both her and her baby good health: painted ceramics, cutlery, sweets or expensive clothing. In Italy, from around 1300 onwards, traditional offerings began to include elaborate birthing trays given to women either just before or just after birth and presented laden with carefully chosen things for her to eat. These deschi da parto, as they were known, are particularly interesting for the actual images they present of the birthing scene itself, often illustrated in painted vignettes on their top or bottom. In a tray from 1428, decorated by the Florentine artist Bartolomeo di Fruosino (c.1366–1441), we see a detailed depiction of a new mother sitting up in bed, perhaps during what was known as the ‘lying-in’ period, a term of around four to six weeks where post-partum women were kept relatively secluded for recovery. Dressed in a cap and red cloak, likely special birthing wear, she is attended by a variety of women. Some sit beside the bed washing and tending to the newborn child, one of whom might be a balia, a wet nurse, and outside, to the left, small figures queue to enter the room, birth gifts in their hands. The mother herself is turning to another woman, who, fittingly, is presenting her with a birthing tray just like the one on which this entire scene is painted.

On the reverse of Fruosino’s tray, an inscription confirms its good intent: ‘May God give health to every woman who gives birth … May the child be born without fatigue or danger.’ Perhaps to lighten the mood further, he also includes the image of a playful young boy, who proudly boasts: ‘I am a baby who lives on a rock, and I urinate silver and gold!’ The birthing scenes on such trays are clearly an idealised picture of an elite event, set in a grand house full of expensive gifts and multiple helpers, some distance from the everyday realities of childbirth for the vast majority of medieval women. Still, they give us a glimpse into an almost totally unrecorded world. Notably, no male physician is present. This is an all-female sphere, the women exchanging gifts, playing music and gesturing to and fro in animated conversation.

72. A desco da parto, or birthing tray, made in Florence in 1428, painted by the artist Bartolomeo di Fruosino.

What impact did all these ideas about pregnancy and birth, menstruation and inferior humours have on the actual lives of medieval women? Certainly the outlook was in many ways bleak. Women’s secondary status carried through into almost every institutional context possible, all of which were fundamentally geared towards the men who had dominated such arenas for centuries. Religious hierarchies, at least those incorporating major positions of political control, were run exclusively by men. The universities in which women’s theology, philosophy and, of course, biology were discussed were male-only domains. And most surviving medieval laws use male pronouns with such frequency as to suggest that the female sex held virtually no autonomous status within certain legal frameworks: court records mostly invoke women via their husbands and fathers in an unpleasant and proprietary fashion. In many ways the Middle Ages can be seen as a deeply troubling time, where anatomy cast half of the population almost as a lower form of human being.

All this is patently true. Yet, as always, the detail of these situations was far more nuanced. The boundaries of medieval women’s lives were, for instance, just as often conditioned by geography as by biology. Compare statistics for marriage at the opposite ends of Europe. From the fragmentary evidence we have, it seems that in the south – Italy, Spain or southern France – most women would have been married by a pretty young age. Many were in their later teens at the time, taking husbands on average a decade or so older than them, and in the rare case of high-status diplomatic brides it could be even younger than this: Blanche of Castile, founder of Maubuisson Abbey and its entrail necropolis, was only twelve when she was made to marry the soon-to-be King Louis VIII of France, himself also twelve at the time. In Europe’s north, however, in London or the Flemish cities of Ghent or Bruges, women appear to have married somewhat later in life. Most only took husbands once in their early twenties, perhaps after a period of employment earning their own wage. Likewise, in both north and south a minority of women married only in their forties and fifties, entering into unions of companionship based on shared comfort, not on the speedy bearing of children. What emerges is a range of marriage models across different cultures, each of which would have impacted on a woman’s quality of life in quite different ways. Some were quickly co-opted without choice into union with a man and the potentially dangerous process of motherhood, while others were able to live out very different existences, entering into the world of work and forging a more independent path. Even the apparently fixed universals of married status could themselves change quickly. A widowed woman might, after the death of her husband, enjoy substantial financial prosperity and independence compared with her younger, married daughter. Partial records found in the storeroom of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo – the largest trove of information we have on medieval Jews, housing more than 300,000 fragmentary texts – suggest that divorce was far more common in Jewish communities than in Christian ones, where the Church had made it almost impossible to dissolve a marriage. Jewish women, on the contrary, could instigate divorce proceedings themselves without their husbands’ permission, and were also allowed afterwards to remarry into more personally or socially advantageous partnerships should they wish.

In the Muslim Middle East and north Africa the situation was different again. The familiar caricature of the medieval harem, in which groups of women might be coupled to a single man through marriage, gives way to more complicated readings in reality. Under Islamic law men could in theory take more than one wife, but this seems not to have happened particularly often. And likewise, while social structures of Muslim marriages were, like their European counterparts, often highly restrictive – wives were described as ideally submissive and demure, and were generally kept to particular parts of the home, with their bodies always fully covered when out in public – these conditions, while overwhelmingly stifling, could also, contrarily, enable certain unique opportunities. Muslim women were able to partake of female-only spaces in a way almost entirely denied their European counterparts. We get a sense of this in an image from a thirteenth-century manuscript showing a gathering of people listening enraptured to a speech by Abu Zayd of Saruj, the main character in a literary work of the Iraqi author Muhammad al-Hariri (c.1054–1122). Here a group of women are present at the top of the scene, perhaps on a balcony overlooking the action. They are shown wrapped in colourful clothes, swirling textures of multi-patterned textile enveloping their bodies. True, they all wear veils, exposing virtually none of themselves save the upper or lower portions of the face. But, separated from the men, they turn and gesture to each other as if in far more engaged conversation than their silent, static male counterparts. Their world is reminiscent of the busy atmosphere depicted in Fruosino’s birthing tray, except that, rather than being a rare moment of exclusively feminine celebration, for these Muslim women speaking with one another outside of male earshot is presented as a typical daily experience.

73. The trickster Abu Zayd of Saruj speaking to an assembled group of men and women, from the Maqamat ( ), or compendium of tales, by the Iraqi author Muhammad al-Hariri. This version of the book was illustrated by a scribe named Yahya al-Wasiti in 1237.

), or compendium of tales, by the Iraqi author Muhammad al-Hariri. This version of the book was illustrated by a scribe named Yahya al-Wasiti in 1237.

Like geography, matters of class could also serve either to exacerbate or to mitigate biological preconceptions of gender. The arranged, socially advantageous marriages of the rich would have seen many wealthy women pressured into a destiny they had not chosen for themselves, something felt far less acutely the lower one got down the social ladder. Yet, unlike the poor, such women were often still able to use family money in the service of personal or social good in the same way as their husbands, free to spend on whatever they wished, from the commissioning of specialised artisans to the foundation of religious or civic institutions. In these upper echelons women could even rise through familial connections to the most serious positions of power possible. One can imagine that Arwa al-Sulayhi (c.1048–1138), the eleventh-century queen of Yemen, would not have been nearly as restricted by her gender as an ordinary Yemeni woman when conducting various important diplomatic missions and making political peace on behalf of her country. Nor do we suppose that the earlier, eighth-century Byzantine empress Irene (752–803) felt quite as oppressed as the women she would rule over from Constantinople after seizing the throne from her twenty-six-year-old son Constantine VI, whom she promptly had arrested and violently blinded, to ensure that he could never retake power. A formidable tactician, Irene’s reign saw her crush theological heresies, found an elite personal guard, and pay for the building of enormous churches that were decorated with lavish schemes in just the same manner as those of male rulers past. Indeed, she sometimes went so far as to take the title Baslieus ( ): ‘Emperor’, not Empress.

): ‘Emperor’, not Empress.

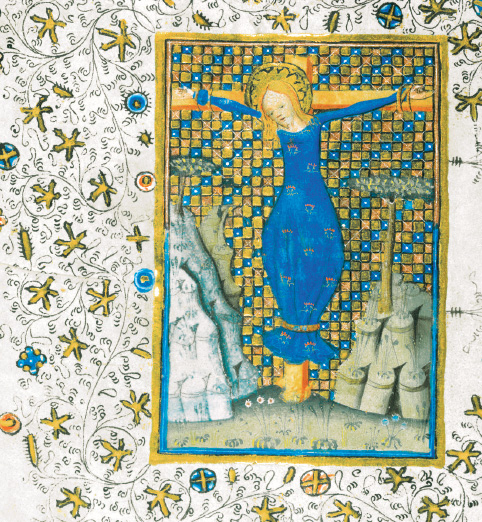

Opportunities for medieval women wishing to side-step altogether the seemingly tough shackles of their patriarchal societies were few, although for some in Europe one option was to enter into a marriage not with a man but with Christ. Becoming a cloistered nun within a church and devoting oneself to an exclusively holy existence hardly feels like a substantial emancipation. But its celibate nature would have at least appealed to women in search of a life without the dangers of childbirth. Just how passionately some desired the protection of the Church comes across forcefully in the vita of an unusual saint named Wilgefortis, who was much venerated in northern Europe from the ninth century onwards. Her name is a corruption of the Latin virgo fortis, ‘strong virgin’, although she was sometimes known by several other remarkable names: Uncumber, Kümmernis, Liberdade and Eutropia. She was, so the story goes, the daughter of a pagan king due to be married off to a neighbouring ruler as part of a peace treaty. Wilgefortis, however, firmly rejected the idea. In her mind she owed spousal devotion only to the crucified Christ, and no amount of coercion would convince her otherwise. For this refusal Wilgefortis was swiftly imprisoned, where she prayed that her appearance might be transformed so as to be found repulsive by all men, leaving her in peace to live out her days chastely in a convent in the service of God. Sure enough, when she was later fetched from her cell, in the words of one source: ‘They found that all her beauty was gone, and her face overgrown with long hair like a man’s beard.’ She was now doubly estranged from her father – both an evangelised Christian and a miraculous hermaphrodite – and in an enraged state he had her tortured and crucified. A horrible death like this was unlikely to have been preferable to marriage for most women, yet the pious example of such saints showcases how seriously many took the alternative religious life of a nun. These were holy women who pushed back against a masculine status quo, their model of pious liberation sanctioned by divine intervention.

74. St Wilgefortis on the cross, from a Book of Hours made in Ghent around 1420.

Tales like that of Wilgefortis make clear too that it is not quite right to see the Middle Ages as a time in which gender was conceived of only as a binary, with powerful men set against weak women. Her image is found sculpted and painted with frequency in the period, and it suggests that the apparently fixed attributes of the sexes could on occasion become blurred: she wears a woman’s dress yet has a man’s bearded face, she was seen as somehow strange through her ‘unnatural’ doubled gender and yet when crucified was venerated as a perfect archetype of holiness. It is almost as if somewhere along the way Wilgefortis’s femininity was suddenly weaponised, an idea we see expressed in the works of several other late medieval women. The fifteenth-century Welsh poet Gwerful Mechain, for example, clearly felt empowered enough to write witheringly of her counterpart male authors, whom she felt shied away from gender as a subject for high art. For her a woman’s body was no site of shame, it was aggressive poetic fuel. As she wrote in one poem, I’r cedor, ‘To the vagina’:

Gerddau cedor i gerdded.

Sawden awdl, sidan ydiw,

Sêm fach, len ar gont wen wiw,

Lleiniau mewn man ymannerch,

Y llwyn sur, llawn yw o serch,

Fforest falch iawn, ddawn ddifreg,

Ffris ffraill, ffwrwr dwygaill deg,

Pant yw hwy no llwy yn llaw,

Clawdd i ddal cal ddwy ddwylaw.

Trwsglwyn merch, drud annerch dro,

Berth addwyn, Duw’n borth iddo.

All you proud male poets, you dare not scoff.

Let songs to the quim grow and thrive

Find their due reward and survive.

For it is silky soft, the sultan of an ode,

A little seam, a curtain on a hole bestowed,

Neat flaps in a place of meeting,

The sour grove, circle of greeting,

Superb forest, faultless gift to squeeze,

Fur for a fine pair of balls, tender frieze.

A girl’s thick glade, it is full of love,

Lovely bush, blessed be it by God above.

In the darker moments of medieval life women were overwhelmingly the victims of men. It is hard to say precisely whether sexual crimes were committed more or less frequently in the Middle Ages than the present, but structures of accountability were certainly far less reliable. Legal records and civic accounts record rape as not an infrequent occurrence, especially in large cities, and we get a sense that punishment for such crimes, enforced by an entirely male legal system, were rarely enacted to their fullest extent. Even when they were, prosecution was typically based on the degree to which a crime had transgressed shared male codes of honour and the limitations they placed on a woman’s social appeal to other men. If a man raped a virgin, despoiling her for potential future unions, he might be forced to marry her himself or at least continue to support her financially as he would a wife. If the victim was already married, the punishment could be significantly more severe, depending on the specifics of the crime and her husband’s background, from a hefty fine through to hanging. A concern for the physical and psychological well-being of the women involved is largely absent.

In the world of fiction and folklore, by contrast, the responsibility for sexual aggression was just as often reversed. One of the many contradictions at the heart of contemporary attitudes towards women was that the womb – and by extension a woman herself – was viewed both as extremely placid, a simplistic vessel waiting to be filled, and at the same time dangerously aggressive, a siren-like, greedy void. The latter prompted severe castration anxiety among medieval men, something frequently brought to the fore in romance narratives. Here male authors voiced fears that mischievous women might wish to do violent harm to their suitor’s penis by various means, inserting sharp iron into the vagina in order to ensnare his member or simply slicing off the penis cleanly from his skin. Stories like this range from genuinely fearful tales to more playful visualisations seen on love tokens, cast into fertility badges, carved evocatively into the lids of small treasure boxes and painted in the margins of medieval manuscripts. One such illustration decorates a famous thirteenth-century French epic poem, the Roman de la Rose, with a pair of nuns comically stuffing their pockets with large penises plucked from a sprouting tree, a masculine equivalent to the kind of floral metaphors used by Gwerful Mechain. This is a simple enough comedic device, found in a number of medieval stories: the cloistered celibate life of a nun was, in theory, as far away from this kind of libidinous plucking as it got. Yet there might be a more reactionary message at work here too. Unusually, this manuscript was not the product of a typical, exclusively male illustrator’s workshop. It was made by the much-esteemed husband-and-wife team Richard and Jeanne de Montbaston, whose atelier in fourteenth-century Paris produced a number of these luxury books. It is even possible that this particular image is the work of Jeanne alone, who continued to write and illustrate independently after Richard’s death in the 1350s. We are left to wonder whether these nuns are painted conforming to masculine stereotypes of female sexual aggression, pocketing penises left, right and centre, or are instead shown being more genuinely rebellious, trying to overturn a phallocentric world in an almost proto-feminist mould.

75. A pair of nuns plucking penises from a tree in the margins of a manuscript of the Roman de la Rose made in Paris in the mid-fourteenth century.

For its part, the penis could end up serving as an important organ of identity for medieval men. We find, for instance, a familiar bragging equation of codpiece size with manliness laced throughout masculine self-image in the Middle Ages. That a man might be openly mocked for the smallness of his penis is shown in a passage from a thirteenth-century Icelandic saga, where a maid comes across the story’s romanticised outlaw hero, Grettir Ásmundarson, naked. Although Grettir was known as a fearsome presence, the maid exclaims to her sister rather disappointedly:

Svá vil ek heil, systir, hér er kominn Grettir Ásmundarson, ok þykki mér raunar skammrifjamikill vera, og liggr berr. En þat þykki mér fádœmi, hversu lítt hann er vaxinn niðr, ok ferr þetta eigi eptir gildleika hans Qðrum.

Bless me, sister, Grettir Ásmundarson is here, and he seems to me well built indeed, and lying here naked. But it seems to me extraordinary how small he is down below. It doesn’t go with his bigness in other respects.

Alternatively, for medieval Jews and Muslims, rituals of circumcision – the brit milah ( ) or khitan (

) or khitan ( ) – elevated the penis as a marker of belonging. While Islamic scholars debated whether the practice was obligatory or simply traditional, for Jews it followed directly in the model of Abraham, a marker of the covenant of the Jewish people with God and an important moment of initiation. This was a time when a young boy might be named, and, unlike the ‘uncontrolled’ blood of menstruation, the officially sanctioned blood of circumcision was theorised by rabbis as having spiritually potent properties, sometimes poured during the ritual onto the ground in front of a synagogue’s Ark. Given that Christ had been born to a Jewish family, some Christians too noted it was technically possible that, although his body had been assumed miraculously to heaven, his foreskin may have remained on earth as a holy relic. This was a controversial claim rebutted by theological critics but was nonetheless embraced by some: the holy woman Catherine of Siena even spoke of a wedding ring for her spiritual marriage to Christ that was formed from the holy prepuce itself. Several Holy Foreskin relics appear in the medieval record, with suspicious frequency given there should have been only a single one to go round. One was venerated in the city of Antwerp, another was displayed in the Spanish pilgrimage capital of Santiago de Compostela, a third was in the eastern French city of Metz, and yet another was in the possession of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne. This last foreskin even claimed a complicated ancestry from the Virgin herself, who had kept it in a small bag after the circumcision before giving it to Saint John. The pouch had then apparently been passed to an angel, who had conveniently deposited it in the imperial court at Aachen, where it was proudly displayed.

) – elevated the penis as a marker of belonging. While Islamic scholars debated whether the practice was obligatory or simply traditional, for Jews it followed directly in the model of Abraham, a marker of the covenant of the Jewish people with God and an important moment of initiation. This was a time when a young boy might be named, and, unlike the ‘uncontrolled’ blood of menstruation, the officially sanctioned blood of circumcision was theorised by rabbis as having spiritually potent properties, sometimes poured during the ritual onto the ground in front of a synagogue’s Ark. Given that Christ had been born to a Jewish family, some Christians too noted it was technically possible that, although his body had been assumed miraculously to heaven, his foreskin may have remained on earth as a holy relic. This was a controversial claim rebutted by theological critics but was nonetheless embraced by some: the holy woman Catherine of Siena even spoke of a wedding ring for her spiritual marriage to Christ that was formed from the holy prepuce itself. Several Holy Foreskin relics appear in the medieval record, with suspicious frequency given there should have been only a single one to go round. One was venerated in the city of Antwerp, another was displayed in the Spanish pilgrimage capital of Santiago de Compostela, a third was in the eastern French city of Metz, and yet another was in the possession of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne. This last foreskin even claimed a complicated ancestry from the Virgin herself, who had kept it in a small bag after the circumcision before giving it to Saint John. The pouch had then apparently been passed to an angel, who had conveniently deposited it in the imperial court at Aachen, where it was proudly displayed.

76. Abraham circumcising himself, from a richly illustrated Bible made in France around 1355.

These medieval religious traditions of the penis managed to take what was fundamentally a sex organ and turn it into a public and distinctly de-sexualised object of brotherhood or sacred veneration. Other groups, however, were pressed into doing the reverse: hiding overtly eroticised male subject matter from society in a far more coded way. Sexual love between two men was viewed within the conservative bounds of the Middle Ages as a corruption of God-given gender norms. Male homosexuals were framed as sodomites, after the inhabitants of the supposedly depraved and promptly destroyed biblical city of Sodom, and we find their existence largely absent from official accounts apart from records of their punishment. Depending on where and when one lived, sentences for sodomitical crimes varied dramatically, from those of the German Empire, whose law codes barely mention such perceived misconduct, through to those of the Venetian Republic, whose fourteenth-century Signori dei Notti, or ‘Night Watch’, would sentence gay men to death by burning at the stake. Some small homosexual communities do seem to have existed during the Middle Ages, although even these remain recorded in only the most derogatory of ways. Richard of Devizes’ twelfth-century chronicle of life in England during the reign of Richard I mentions a number of what he saw as sexually deviant characters amid London’s medieval nightlife: alongside farmacopolae (‘drug pedlars’) and crissariae (‘prostitutes’), he lists glabriones (‘effeminate boys’), pusiones (‘rent boys’), vultuariae (‘witches’) and mascularii (‘man-lovers’).

Leniency for such sodomitic crimes might in fact depend on the degree to which a gay man strayed outside regular sexual roles. The most unpleasant homophobic rhetoric was reserved for the passive homosexual, whose penetration meant his experience of sex was transformed into an unacceptably feminine mode. By comparison, the active penetrator was thought at least to be dispensing something of the typical male sexual responsibility, albeit with a moral wrong-headedness. Following a similar gendered logic, gay women were recorded even less frequently in the Middle Ages than gay men. Lesbians were members of society who were by definition twice as inferior, both by their homosexual orientation and their secondary female gender. They only very rarely feature in literary stories of the era, and even then they tend to exchange mostly non-physical affection. A tale found in the tenth-century Jawami’ alladhdha (‘Encyclopedia of Pleasure’), by the little-known author Ali ibn Nasr al-Katib, tells of two princesses named Hind and al-Zarqa who fall in love and found a monastery together. But theirs is an amorousness of a particularly chaste variety, presented as a model of female loyalty and certainly not praise for open sapphic love itself.

One aspect of the genitals united all people, female and male, Jewish and Christian, homosexual and heterosexual alike: eventually, everyone needs to urinate. Within the modes of humoral medicine everything that was expelled from the body – sweat, vomit, saliva, faeces – could be pored over for its quality and quantity by a knowledgeable healer for signs of underlying internal imbalance, and urine was no exception.

Texts from as early as the seventh century offered detailed guidance for physicians in uroscopic readings. We agree today that urine colour can be an indicator of levels of hydration within the body as well as various other measures of health, but this earlier medicine took urological divining to extremes. So focused were some physicians on reading urine that the round-bottomed flasks in which patients’ samples were presented to them quickly became a prominent part of their visual culture. Much like a modern white coat, a person in a medieval manuscript depicted peering at such a flask instantly identified himself as a physician, although this was not necessarily a reifying gesture of respect. In the fifteenth-century stained-glass windows of York Minster, monkeys rather than men inspect urine bottles, a bawdy pastiche of the active medical scene in the city. In theatrical plays, too, bungling doctors also offered light comic relief through the bladder. In the so-called Croxton Play of the Sacrament, a rare surviving piece of English religious theatre, a character called Master Brownditch of Brabant – whose name already suggests a certain coprological obsession – is described in particularly urine-laden terms:

The most famous phesycyan

That ever sawe uryne!

He seeth as wele at noone as at nyght,

And sumtyme by a candelleyt

Can gyf a judgyment aryght

As he that hathe noon eyn.

The most famous physician That ever saw urine! He sees as well at noon as at night, And sometimes by a candlelight Can give a judgement just as well As one that has no eyes at all.

Urine is both Brownditch’s badge of honour and his failing, the proud marker of his trade and the basis for a backhanded compliment that his urological pronouncements are no better than those of a blind man.

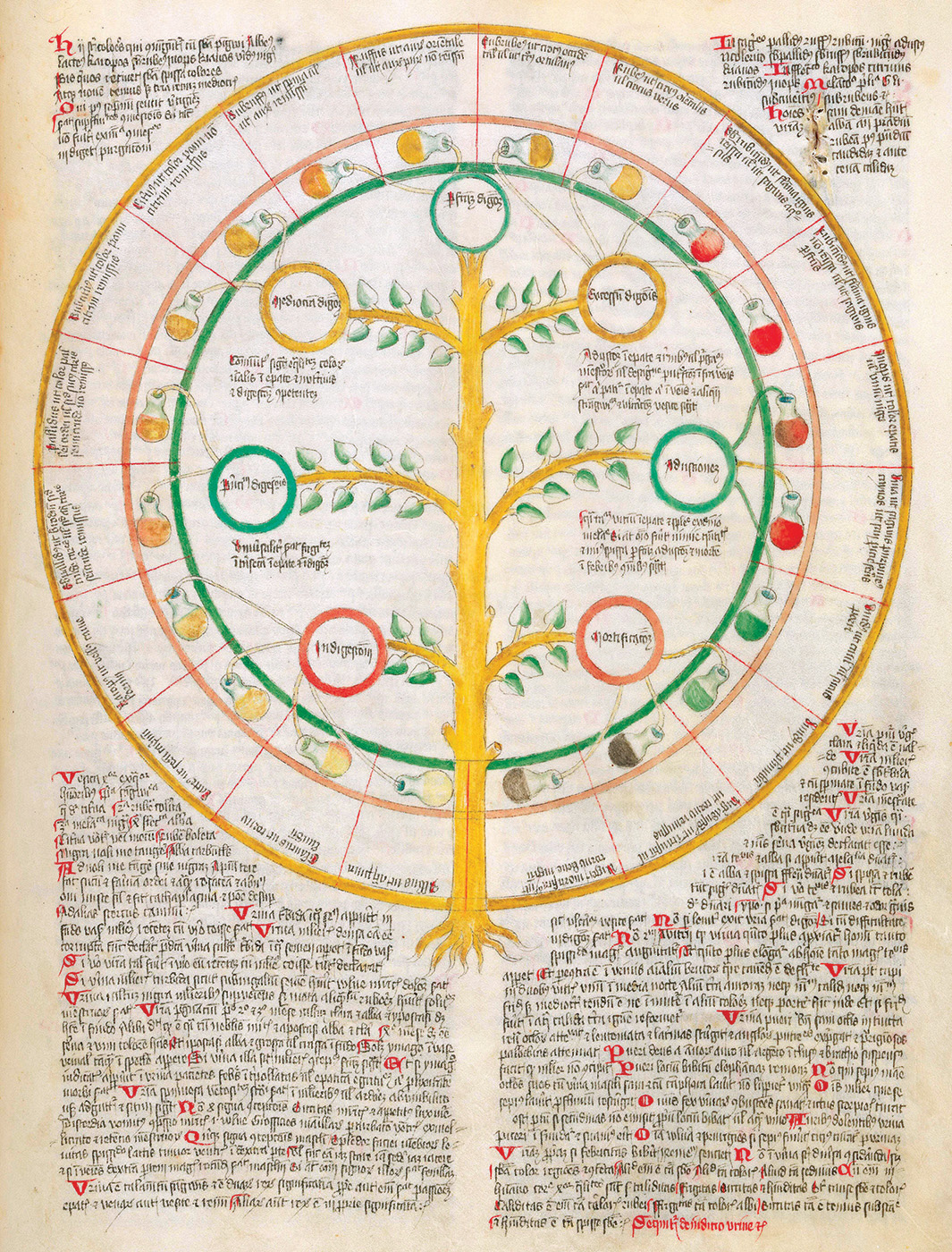

These colourful characters of the stage could be matched medically with equally colourful images. A beautiful tree complete with flowering roundels of piss sounds like something of a paradox, and yet this is how several medieval texts on uroscopy chose to frame their contents. A wheel of samples from a manuscript made around 1420 in Germany shows the detail that went into such prognoses, the culmination of many different theories on micturition. A circle of flasks are shown graded by colour around a flourishing, seven-branched tree, a style of illustration that simultaneously echoes contemporary philosophical diagrams of virtues and vices, religious family trees mapping the genealogy of Christ and, in a way, the penis tree of the Roman de la Rose. Each branch suggests a different broad diagnosis, ranging from indigestion to imminent death, while an outer layer offers abstract colorific descriptions picked up by the corresponding sample’s shade. Lowest on the scale we find albus (‘white’), with the explanation that such urine is ‘as clear as well-water’. The circles then move through various grades of yellow – karopos (likened to camel’s hair or skin), subpallidus (like unreduced meat juice), rufus (like a fine gold or saffron) – before turning to different reds – rubicundus (like a low flame), inops (like an animal’s liver) and kyanos (like a darkened wine). Finally, after covering ever deeper greens – plumbeus (like the colour of lead) and viridis (like a cabbage) – the wheel finishes with two ominous shades of black, one described as being like ink and the other the colour of a darkened animal horn.

77. A wheel of urine sprouting from a tree, from a German medical manuscript made around 1420.

These vivid descriptions of urine show just how sensory a task physicians were undertaking when inspecting patients’ samples, with uroscopy texts encouraging all sorts of behaviour at the bedside: testing the viscosity of the urine and any particles suspended within, grading its smell or evaluating its sweetness or bitterness. Shaken, stirred, sniffed, even tasted, urine was reified in such flourishing trees, turned from effluvia to a careful diagnostic tool. In fact, just like the topsy-turvy medieval ideas of the anus, the notion of elevating something base to something extremely sensitive is a good model for how the Middle Ages seem to have viewed the genitals in general. We are often encouraged to look back on their views of gender and sexuality as rather blunt, switching robotically between only two modes. On the one hand, there is the coyness of courtly love or religious celibacy, a chastity that separated the genders and saw sex as sin, something best avoided or at least uncomfortably repressed. On the other, there is the overstimulated titillation of something like Jeanne’s penis tree, a raw eroticism that could demonise both genders and tip all too easily into sexual danger and violence. Yet the work of authors and makers at the time shows that neither stereotype was strictly uniform. Medieval sex organs do not seem to have been discussed all that much more or less than in our own sexual lives today. But their genitals were certainly more momentous: no other part of the medieval body played such a defining role as the womb or the penis in plotting the bounds of how a person’s life might unfold.

78. A watercolour showing the amputation of the foot of Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich III, with eight attendant physicians and surgeons, painted around 1493.