There will always be more to say about the medieval body. Like bodies today, the more closely we look, the more we realise that all sorts of patterns are appearing before our eyes. This book has only scratched the surface of the different ways in which people of the past saw themselves. Their human forms were at once a place for debating and developing the complicated theories of the ancients, a conduit for sensual engagement with the world around them, a stage for performing a cacophony of different sexual, religious and racial identities, and a canvas for aesthetic ideas, from ugliness and pain to the most ecstatic beauty. The body was everything to everyone.

Throughout the Middle Ages people tried to predict what would happen to their own bodies in the future. Spiritual thinking supplied various solutions to the perilous uncertainty of times to come. Eschatological prophecies both biblical and contemporary promised thunderous revelation, moral judgement and the revival of corpses for either fearsome damnation or salvation in an eternal messianic age. Secular literature similarly dreamed of parallel futures: in the fantastical, almost sci-fitale of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, retold across Europe and the Middle East from the sixth century onwards, a group of men seal themselves in a cave overnight, awaking only to discover that they have somehow slept for three hundred years. Medieval philosophers, too, grappled with abstract questions of the world to come. Can we ever truly know the nature of change? Is the future handed down to us by fate, divine or otherwise? If so, do we ever really have any freedom, any choice in our actions? Or can we somehow bend this ordained true path to point in any direction we want it?

By the beginning of the sixteenth century this medieval world was indeed poised to change significantly. A whole host of ideas that had been unshakable for centuries were on the turn. In 1492 Spanish ships crossed the Atlantic, bringing back news of an entirely new continent. Between 1497 and 1499 Portuguese sailors rounded the southern tip of Africa, reshaping centuries-old maps and forging vital new sea routes to the Far East. And in 1522, some two thousand years after the idea began to be floated by the ancient Greeks, the first maritime circumnavigation of the planet proved for certain that the earth was a sphere. All sorts of other fixities were likewise flipping and tumbling. From 1512 the reigns of Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent saw the Ottoman Empire grow with speed, unifying vast swathes of eastern Europe, Anatolia, the Middle East and north Africa for the first time in centuries. Meanwhile, in western Europe, religious and political allegiances were being completely redrawn after Martin Luther’s publication in 1517 of his ‘Ninety-Five Theses’, effectively kick-starting the Reformation and setting the Catholic Church on the road to schism. Medicine, too, expanded in this era of new horizons. Ingredients available from the New World were combined with novel forms of experimental chemistry espoused by the dynamic and controversial Swiss physician Paracelsus (c.1493–1541), leading to a shift away from the four classical humours towards a broader array of pharmaceutical cures. And a new wave of exploratory anatomists, among them the Italian Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (1466–1530), the Frenchman Charles Estienne (c.1505–1564) and the Netherlander Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), began to open the body with revived interest, intent on observing afresh what they actually saw beneath the skin.

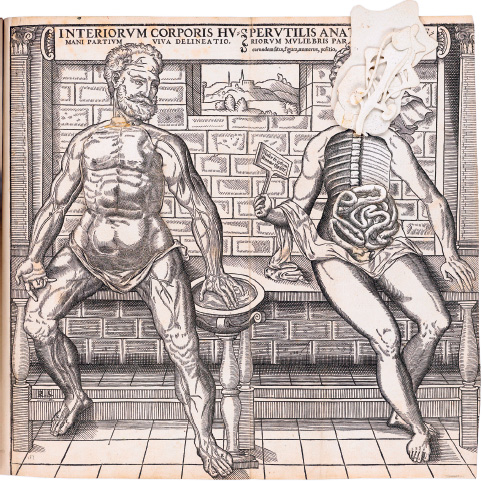

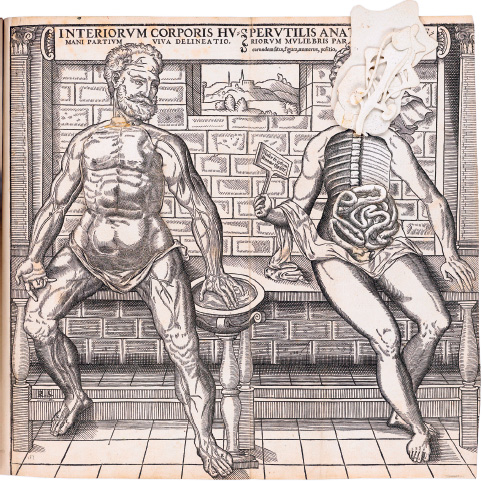

86. An anatomical diagram of a man and a woman, probably printed in London in 1559. The figures are presented with folding flaps of anatomical details that the viewer could peel back layer by layer to uncover the interior beneath. The woman holds a small sign bearing the Latin dictum Nosce te ipsum, ‘Know thyself’.

Few medieval thinkers had divined any of these things in their future, and perhaps as a result they are often swept away in the wake of the sixteenth century’s narrative of dramatic change. I began this book by thinking about how our view of historical moments like the Middle Ages can end up saying as much about the present as it does about the past, but this is equally true of the early modern era that followed it. Just as the term ‘medieval’ tends today to be conflated with a certain muddiness or backward way of thinking, so too have we set the ‘renaissance’ up to be nothing but a success. In its very name it is presented as a rebirth, a period of life following a period of death, in Francesco Petrarca’s words the moment ‘when the darkness has been dispersed’. We admire this generation for their quick turnover of ideas because that is what we, at least for the last century or so, have admired the most in ourselves, in our own change-driven modern society. They seem to be asking the questions we would ask, rolling back boundaries, pushing for the new and the innovative. The argument for the Middle Ages rests on a different set of far less glamorous standards: continuity, consistency, reflection, an ability to keep an idea alive come good times and bad. But we must not forget that looking back and looking forward are complementary things. Without medieval people preserving the classics in their copies and commentaries from Baghdad to Constantinople to Salerno to Paris, early modern people would have been left with little of substance to so dramatically rethink.

What, then, is the future of our understanding of medieval bodies? This, I think, also hinges on looking simultaneously backwards and forwards, keeping one eye on the past and the other on what is coming up ahead. Our world is evolving more quickly than at any time in history, even by the seemingly chaotic pace of the sixteenth century. And we are now able to combine the slow, meticulous process of research into the past – careful readings of art, poetry, religious texts, folk stories, medical cures – with rapidly developing technologies to push our discoveries in all sorts of unforeseen directions.

We also have more and more medieval bodies to hand. The Museum of London’s Centre for Human Bioarchaeology holds the partial skeletons of over 20,000 people from various periods that have been revealed from the capital’s core, and similar finds continue all the time in the most inauspicious of places. In 2015 excavations in the basement of a Paris supermarket turned up some 200 medieval bodies at the site of a former hospital. In 2016 planned extensions to Aberdeen’s Art Gallery revealed at least 92 bodies, probably buried on the site when it was a thirteenth-century friary. In 2017 excavations were completed in Rome on a group of 38 graves, part of a small medieval Jewish cemetery found after renovation work to the new headquarters of an insurance company. And this is more than just an urban phenomenon. After a particularly stormy winter in the Irish town of Collooney, in County Sligo, strong winds toppled a 215-year-old beech tree which dragged with it from the ground the body of an eleventh- or twelfth-century boy whose skeleton had become entangled in its growing roots.

87. The excavation of a medieval plague pit in London. The graves were revealed during digging to install the new Crossrail train line.

If properly catalogued and cleaned, a wealth of information can be found just by looking at these medieval remains. Most obviously, abnormal bones tell a rich tale. Unexpected breaks, fractures and other damage might point to a severe bodily trauma, suggesting particular and often violent causes of death. And more benign deformities of fused or worn bone could indicate that an individual had lived for some time with certain categories of joint problem or congenital issues that warped the bones, telling us something of the conditions that they enjoyed or endured in life. More recently, however, developments in increasingly sophisticated types of technical analysis mean that we can learn even more detail of past medieval lives. Since the 1980s, bioarchaeologists have been getting better and better at searching the densest, best-protected parts of skeletons, like the pulp of the teeth or the temporal bone located in the skull behind the ear, for preserved samples of ancient DNA. This aDNA, as it is known, can be extracted, amplified, sequenced into the correct order and compared with other historical and modern examples to present a unique profile of the skeleton sampled. Even from the most fragmentary of remains we can now tell a person’s sex, their likely geographical or ethnic background and whether or not they suffered from certain genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis or anaemia. Studies can even run similar tests on the aDNA of the microscopic bacteria that once inhabited the fibres of these historical bodies, a process that has revealed a range of historic strains from plague to tuberculosis to leprosy.

Such groundbreaking techniques are not only at work on skeletons either. Methods like this can help us uncover new stories about every type of object mentioned in the chapters of this book. The parchment pages of manuscripts or the leather of historic shoes can be tested to discover what kind of animal they were formed from and where they were bred. The cloth of ancient textiles or the wood of holy relics can be traced by their dyes or plant matter to particular times and individual regions of the medieval world. Sometimes in these researches objects are even treated just like bodies. In 2007 the large thirteenth-century casket reliquary of Saint Amandus, a seventh-century bishop of Maastricht, underwent investigation in the technical department of its current home at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. To find out more about the piece, the gloved hands of conservators cut away small sections of the reliquary’s copper skin from its wooden core with blades and scalpels. Its metal plaques were investigated microscopically, in the manner of skin or blood samples. And the entire work was then transported to the nearby University of Maryland Medical Center, where it was placed inside a Computed Tomography X-ray scanner, a machine normally reserved for living Baltimore citizens. The results were analysed for clues about the reliquary by both the Walters conservation team and a group of diagnostic radiologists from the Medical Center itself, doctors and historians in dialogue.

88. The twelfth-century casket reliquary of Saint Amandus being scanned in a Computed Tomography X-ray scanner at the Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore.

This is the future of medieval bodies. Like centuries-old patients, we examine objects and human remains alike with care. We search out their case histories, trawling through the archives to find fragments of information that help us begin to build up a picture of their past lives. We send their samples to the lab for analysis, using sophisticated processes to help us draw the net tighter. And then, pooling together all of this expertise, we diagnose them: sixth-century, Arabic, female, silver, painted, German, thirteenth-century, male, Egyptian, alabaster and so on. Like the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, these are bodies that have not been roused for centuries. Now they are awake and chattering like never before.