Building the village of your story

Creating and utilizing your setting

Jane Austen told her niece Anna, an aspiring writer, that ‘three or four families in a country village is the very thing to work on’,1 and there’s something particularly interesting and satisfying about the scale and dynamics of a village. Two hundred years since the publication of Emma, thinking about the ‘village’ of your story can help you with plotting, managing your cast of characters, building tension and creating a sense of place, whether your setting is inner-city or rural, contemporary, historical or futuristic. The exercises in this chapter will help you to lead your readers into a convincing world.

When I got married in my late twenties I was part of a group of friends from university all doing the same thing within the same couple of years. Everybody seemed to have the same number of guests or at least people that they felt they should invite. We joked about how people’s ‘social capacity’ seemed to be identical. Weddings in Jane Austen’s time were smaller affairs and took place in the morning. In Emma (Chapter 55) Mrs Elton criticizes Miss Woodhouse and Mr Knightley’s wedding ‘from the particulars detailed by her husband’ (she didn’t get to go) and thought it all extremely shabby, and very inferior to her own. ‘Very little white satin, very few lace veils; a most pitiful business!’

What I now know is that my own and my friends’ guest lists were about equal to Dunbar’s Number, which is around one hundred and fifty. Anthropologist Robin Dunbar found that this is the ideal size for a community, whether a military unit, an Amish village, a business or a group of friends (the sort who are actual friends and relations) on Facebook.2 Villages in eighteenth-century England were around this size, just as they had been at the time of the Domesday Book.

The idea of building the village of your story occurred to me when I was rereading Emma. It is the quintessential village novel. If you are writing a story about a quest or ‘a voyage and return’ then the village model won’t apply so much to you, but if you are penning something set in a particular community, whether it is a neighbourhood, a school, an office, a Brownie pack or whatever, thinking about the village of your story should help.

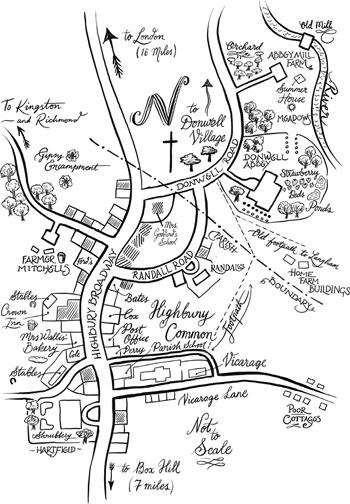

It is easy to map Highbury. Jane Austen may have done this herself and certainly had a functioning map in her head. We are given plenty of information so that readers can picture the village, its layout and position: London is sixteen miles away; Mr Knightley can easily walk the mile from his home to Emma’s; the Westons live only half a mile from Emma’s home, Hartfield; and we are told what Emma sees from the doorway of Ford’s, exactly where the Gypsies are camped, what one passes on the way to the vicarage and much more. Emma rarely leaves Highbury, but other people, particularly men, come and go. Frank Churchill is able to leave on a whim to get his hair cut – and secretly buy a piano. At the end of the novel Emma is at last able to leave the village and go to the seaside.

A map of Highbury

EXERCISE: MAPPING THE VILLAGE OF YOUR STORY

Start a map as soon as you start your story. Keep it in the front of your notebook or pinned above your desk, adding to it and amending it as your story progresses. Readers will be able to tell if your ‘village’ isn’t properly worked out. They will feel jolted out of the story if the geography doesn’t make sense. Interiors of buildings are important too. Draw plans of these. Readers might need to know if a person upstairs can hear what is going on in the kitchen and what a visitor will see when the front door is opened.

PRIVATE SPACES, SHARED SPACES, PUBLIC SPACES3

In Emma we see the characters at church, meeting in and around the village, at balls and at Ford’s, which is ‘the principal woollen-draper, linen-draper, and haberdasher’s shop united; the shop first in size and fashion in the place’ and the site of significant meetings. In Chapter 24 Frank Churchill shows that he understands the importance of Ford’s.

At this moment they were approaching Ford’s, and he hastily exclaimed, ‘Ha! this must be the very shop that every body attends every day of their lives, as my father informs me. He comes to Highbury himself, he says, six days out of the seven, and has always business at Ford’s. If it be not inconvenient to you, pray let us go in, that I may prove myself to belong to the place, to be a true citizen of Highbury. I must buy something at Ford’s. It will be taking out my freedom. – I dare say they sell gloves.’

‘Oh! yes, gloves and every thing. I do admire your patriotism. You will be adored in Highbury. You were very popular before you came, because you were Mr Weston’s son – but lay out half a guinea at Ford’s, and your popularity will stand upon your own virtues.’

How well do you know the spaces in your story?

EXERCISE: MAKE A LIST OF THE DIFFERENT SPACES IN YOUR STORY

This list may grow as the work progresses. A character’s private space may be their bedroom, car, shed or perhaps just a locker if they are at school or in hospital. Shared spaces might be the areas between the beds in a dormitory, shared hallways and drives, communal areas where bins are kept and so on. Public spaces are invaluable for the writer – that’s why there are so many launderettes, cafes, pubs and squares in soap operas and sitcoms. A space may be controlled by an individual such as a pub landlord or be owned by certain people but still function as a public area.

Existing in public and shared space

The picnic at Box Hill in Emma Chapter 43 is an example of characters being let loose in a public space. Jane Austen’s readers might well have been familiar with images of Box Hill, and the outing is much anticipated in the novel: ‘Emma had never been to Box Hill; she wished to see what every body found so well worth seeing.’

They had a very fine day for Box Hill; and all the other outward circumstances of arrangement, accommodation, and punctuality, were in favour of a pleasant party. Mr Weston directed the whole, officiating safely between Hartfield and the Vicarage, and every body was in good time. Emma and Harriet went together; Miss Bates and her niece, with the Eltons; the gentlemen on horseback. Mrs Weston remained with Mr Woodhouse. Nothing was wanting but to be happy when they got there. Seven miles were travelled in expectation of enjoyment, and every body had a burst of admiration on first arriving; but in the general amount of the day there was deficiency. There was a languor, a want of spirits, a want of union, which could not be got over. They separated too much into parties. The Eltons walked together; Mr Knightley took charge of Miss Bates and Jane; and Emma and Harriet belonged to Frank Churchill. And Mr Weston tried, in vain, to make them harmonize better. It seemed at first an accidental division, but it never materially varied. Mr and Mrs Elton, indeed, shewed no unwillingness to mix, and be as agreeable as they could; but during the two whole hours that were spent on the hill, there seemed a principle of separation, between the other parties, too strong for any fine prospects, or any cold collation, or any cheerful Mr Weston, to remove.

It’s significant that Jane Fairfax isn’t mentioned by name in the list of who sets out – she is just ‘Miss Bates’ niece’ – and a person reading the novel for the first time would, like Emma, probably pay little attention to her presence or realize that Frank Churchill’s behaviour is more to do with Jane Fairfax than Emma, the one he flirts with.

At first it was downright dullness to Emma. She had never seen Frank Churchill so silent and stupid. He said nothing worth hearing – looked without seeing – admired without intelligence – listened without knowing what she said. While he was so dull, it was no wonder that Harriet should be dull likewise, and they were both insufferable.

When they all sat down it was better; to her taste a great deal better, for Frank Churchill grew talkative and gay, making her his first object. Every distinguishing attention that could be paid, was paid to her. To amuse her, and be agreeable in her eyes, seemed all that he cared for – and Emma, glad to be enlivened, not sorry to be flattered, was gay and easy too, and gave him all the friendly encouragement, the admission to be gallant, which she had ever given in the first and most animating period of their acquaintance; but which now, in her own estimation, meant nothing, though in the judgment of most people looking on it must have had such an appearance as no English word but flirtation could very well describe. ‘Mr Frank Churchill and Miss Woodhouse flirted together excessively.’ They were laying themselves open to that very phrase – and to having it sent off in a letter to Maple Grove by one lady, to Ireland by another.

The drama of a landscape can enhance a scene. There is also something about letting characters loose in a public space that can lead to them behaving in unanticipated ways. Normal expectations are removed. Characters may have conflicting expectations and feelings about the ownership of spaces and events. How will your public and shared spaces impact on your plot? You can also use them to introduce new characters. Who else might be encountered in these places? Think of the way that in Persuasion, Chapter 12, Anne Elliot and William Elliot see each other in Lyme:

When they came to the steps, leading upwards from the beach, a gentleman, at the same moment preparing to come down, politely drew back, and stopped to give them way. They ascended and passed him; and as they passed, Anne’s face caught his eye, and he looked at her with a degree of earnest admiration which she could not be insensible of. She was looking remarkably well; her very regular, very pretty features, having the bloom and freshness of youth restored by the fine wind which had been blowing on her complexion, and by the animations of eye which it had also produced. It was evident that the gentleman, (completely a gentleman in manner) admired her exceedingly. Captain Wentworth looked round at her instantly in a way which shewed his noticing of it. He gave her a momentary glance, a glance of brightness, which seemed to say, ‘That man is struck with you, and even I, at this moment, see something like Anne Elliot again.’

The seaside, for Jane Austen, is a place for romance, adventure, chance meetings and, in the cases of Lydia Bennet and Georgiana Darcy, misadventure. When characters are removed from their usual spheres, anything might happen.

In another important scene in Emma we see the characters literally negotiating the use of space. Frank Churchill and Emma are determined to have a ball, and when the Westons’ house is deemed not suitable, Frank Churchill has the idea of using the Crown Inn. We see the characters’ reactions to the space and their machinations to ensure that they all get what they want. Mr Woodhouse shows himself to be more astute and a better judge of character than many might give him credit for; he can see that because Frank Churchill is inclined to open windows and leave doors gaping, he is ‘not quite the thing’, something that it takes Emma a lot longer to realize.

Here are the residents of Highbury planning a ball (from Emma, Chapter 29):

It may be possible to do without dancing entirely. Instances have been known of young people passing many, many months successively, without being at any ball of any description, and no material injury accrue either to body or mind; – but when a beginning is made – when the felicities of rapid motion have once been, though slightly, felt – it must be a very heavy set that does not ask for more.

Frank Churchill had danced once at Highbury, and longed to dance again; and the last half-hour of an evening which Mr Woodhouse was persuaded to spend with his daughter at Randalls, was passed by the two young people in schemes on the subject. Frank’s was the first idea; and his the greatest zeal in pursuing it; for the lady was the best judge of the difficulties, and the most solicitous for accommodation and appearance.

They first think of having the ball at Randalls, the Westons’ house.

The doors of the two rooms were just opposite each other. ‘Might not they use both rooms, and dance across the passage?’ It seemed the best scheme; and yet it was not so good but that many of them wanted a better. Emma said it would be awkward; Mrs Weston was in distress about the supper; and Mr Woodhouse opposed it earnestly, on the score of health. It made him so very unhappy, indeed, that it could not be persevered in.

‘Oh! no,’ said he; ‘it would be the extreme of imprudence. I could not bear it for Emma! – Emma is not strong. She would catch a dreadful cold. So would poor little Harriet. So would you all. Mrs Weston, you would be quite laid up; do not let them talk of such a wild thing. Pray do not let them talk of it. That young man (speaking lower) is very thoughtless. Do not tell his father, but that young man is not quite the thing. He has been opening the doors very often this evening, and keeping them open very inconsiderately. He does not think of the draught. I do not mean to set you against him, but indeed he is not quite the thing!’ [. . .]

Before the middle of the next day, he [Frank Churchill] was at Hartfield; and he entered the room with such an agreeable smile as certified the continuance of the scheme. It soon appeared that he came to announce an improvement.

‘Well, Miss Woodhouse,’ he almost immediately began, ‘your inclination for dancing has not been quite frightened away, I hope, by the terrors of my father’s little rooms. I bring a new proposal on the subject: – a thought of my father’s, which waits only your approbation to be acted upon. May I hope for the honour of your hand for the two first dances of this little projected ball, to be given, not at Randalls, but at the Crown Inn?’

‘Yes; if you and Mr Woodhouse see no objection, and I trust you cannot, my father hopes his friends will be so kind as to visit him there. Better accommodations, he can promise them, and not a less grateful welcome than at Randalls. It is his own idea. Mrs Weston sees no objection to it, provided you are satisfied. This is what we all feel. Oh! you were perfectly right! Ten couple, in either of the Randalls rooms, would have been insufferable! – Dreadful! – I felt how right you were the whole time, but was too anxious for securing any thing to like to yield. Is not it a good exchange? – You consent – I hope you consent?’

‘It appears to me a plan that nobody can object to, if Mr and Mrs Weston do not. I think it admirable; and, as far as I can answer for myself, shall be most happy – It seems the only improvement that could be. Papa, do you not think it an excellent improvement?’

She was obliged to repeat and explain it, before it was fully comprehended; and then, being quite new, further representations were necessary to make it acceptable.

‘No; he thought it very far from an improvement – a very bad plan – much worse than the other. A room at an inn was always damp and dangerous; never properly aired, or fit to be inhabited. If they must dance, they had better dance at Randalls. He had never been in the room at the Crown in his life – did not know the people who kept it by sight. – Oh! no – a very bad plan. They would catch worse colds at the Crown than anywhere.’ [. . .]

‘From the very circumstance of its being larger, sir. We shall have no occasion to open the windows at all – not once the whole evening; and it is that dreadful habit of opening the windows, letting in cold air upon heated bodies, which (as you well know, sir) does the mischief.’

‘Open the windows! – but surely, Mr Churchill, nobody would think of opening the windows at Randalls. Nobody could be so imprudent! I never heard of such a thing. Dancing with open windows! – I am sure, neither your father nor Mrs Weston (poor Miss Taylor that was) would suffer it.’

EXERCISE: NEGOTIATING AND USING PUBLIC AND SHARED SPACE

Write a scene which involves characters in public or shared space. What conflicts, feuds, romances or friendships will arise? How will people’s behaviour be judged by others? The space needn’t be outdoors. How does being in public or shared space affect the dialogue and the scene as a whole?

Thinking about your characters in their private space

In Emma, Chapter 42, faced with leaving Highbury to become a governess and unable to be with the man she secretly loves, Jane Fairfax confides a little of how she feels. She has almost no private space and longs for just a few moments by herself.

Jane Fairfax appeared, coming quickly in from the garden, and with a look of escape. – Little expecting to meet Miss Woodhouse so soon, there was a start at first; but Miss Woodhouse was the very person she was in quest of.

‘Will you be so kind,’ said she, ‘when I am missed, as to say that I am gone home? – I am going this moment. My aunt is not aware how late it is, nor how long we have been absent – but I am sure we shall be wanted, and I am determined to go directly. – I have said nothing about it to any body. It would only be giving trouble and distress. Some are gone to the ponds, and some to the lime walk. Till they all come in I shall not be missed; and when they do, will you have the goodness to say that I am gone?’

‘Certainly, if you wish it; – but you are not going to walk to Highbury alone?’

‘Yes – what should hurt me? – I walk fast. I shall be at home in twenty minutes.’

‘But it is too far, indeed it is, to be walking quite alone. Let my father’s servant go with you. – Let me order the carriage. It can be round in five minutes.’

‘Thank you, thank you – but on no account. – I would rather walk. – And for me to be afraid of walking alone! – I, who may so soon have to guard others!’

She spoke with great agitation; and Emma very feelingly replied, ‘That can be no reason for your being exposed to danger now. I must order the carriage. The heat even would be danger. – You are fatigued already.’

‘I am,’ – she answered, – ‘I am fatigued; but it is not the sort of fatigue – quick walking will refresh me. – Miss Woodhouse, we all know at times what it is to be wearied in spirits. Mine, I confess, are exhausted. The greatest kindness you can shew me, will be to let me have my own way, and only say that I am gone when it is necessary.’

Emma had not another word to oppose. She saw it all; and entering into her feelings, promoted her quitting the house immediately, and watched her safely off with the zeal of a friend. Her parting look was grateful – and her parting words, ‘Oh! Miss Woodhouse, the comfort of being sometimes alone!’ – seemed to burst from an overcharged heart, and to describe somewhat of the continual endurance to be practised by her, even towards some of those who loved her best.

In Pride and Prejudice Mr Bennet retreats to his library – sometimes pursued by Mr Collins. In Sense and Sensibility the Dashwood sisters and their mother lose their home, Norland Park. In Mansfield Park (Chapter 19) an invasion of the private space of Lord Bertram’s study is emblematic of the wrongness of the theatricals and the way that the Bertrams, Crawfords and Mr Yates have been moving the normal boundaries of their previously ordered existence. ‘Sir Thomas had been a good deal surprised to find candles burning in his room; and on casting his eye round it, to see other symptoms of recent habitation and a general air of confusion in the furniture. The removal of the bookcase from before the billiard-room door struck him especially.’

Write about a character whose private space is invaded or threatened, or about an attempt to annexe a character’s private space.

Emma is a snob and has a very particular view of Highbury society and her place within it. Readers see how the village functions and how things and attitudes change. At the start of the novel there are people she will not mix with, and she tells Harriet Smith that she will not be able to continue their friendship if Harriet marries Robert Martin. All villages have their spoken and unspoken rules, codes and traditions. These might determine who is in charge of what, who parks where, what sort of present is or isn’t acceptable for a schoolteacher at the end of term, etc.

Think about how the society you are writing about operates. How do different characters feel about the rules, codes and traditions of your village? The fun starts when somebody threatens to break the rules. In one of my favourite films, Serial Mom, which stars Kathleen Turner, wearing white shoes after Labor Day or failing to sort your recycling has fatal consequences.

1.Write the Ten Commandments of your village.

2.Now write a scene in which somebody breaks one or more of the rules; this could be from the point of view of a rule breaker, a rule enforcer or a bystander.

All literature, in an axiom attributed to Tolstoy, is either a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town. This certainly seems true in the work of Jane Austen. In Emma the arrivals of Frank Churchill, Jane Fairfax and Mrs Elton are catalysts for change, comedy, romance and drama. In Austen’s novels readers see many characters setting out on journeys (Catherine Morland and Anne Elliot are prime examples) and strangers coming to town (Mr Bingley, Mr Darcy, Mr Collins, Wickham, the Crawfords).

More on journeys later, but for now think about the way that a stranger coming into the village of your novel can be your inciting incident or move your plot in a new direction. In Jane Austen’s work it is striking how often women wait for news, for things to happen and for people to arrive, a situation that Jane must have known only too well, for example waiting for news of her sailor brothers. Here she is writing to Cassandra in November 1801.

We have at last heard from Frank; a letter from him to you came yesterday, and I mean to send it on as soon as I can . . . En attendant, you must rest satisfied with knowing that on the 8th of July the ‘Petterel,’ with the rest of the Egyptian squadron, was off the Isle of Cyprus, whither they went from Jaffa for provisions, &c., and whence they were to sail in a day or two for Alexandria, there to wait the result of the English proposals for the evacuation of Egypt. The rest of the letter, according to the present fashionable style of composition, is chiefly descriptive. Of his promotion he knows nothing.

Austen’s readers often come across heroines looking out of windows, longing for people to arrive or being surprised by sudden arrivals or communications. This is from Chapter 53 of Pride and Prejudice.

The housekeeper at Netherfield had received orders to prepare for the arrival of her master, who was coming down in a day or two, to shoot there for several weeks. Mrs Bennet was quite in the fidgets. She looked at Jane, and smiled and shook her head by turns.

‘Well, well, and so Mr Bingley is coming down, sister,’ (for Mrs Philips first brought her the news). ‘Well, so much the better. Not that I care about it, though. He is nothing to us, you know, and I am sure I never want to see him again. But, however, he is very welcome to come to Netherfield, if he likes it. And who knows what may happen? But that is nothing to us. You know, sister, we agreed long ago never to mention a word about it. And so, is it quite certain he is coming?’

‘You may depend on it,’ replied the other, ‘for Mrs Nicholls was in Meryton last night; I saw her passing by, and went out myself on purpose to know the truth of it; and she told me that it was certain true. He comes down on Thursday at the latest, very likely on Wednesday. She was going to the butcher’s, she told me, on purpose to order in some meat on Wednesday, and she has got three couple of ducks just fit to be killed.’

Miss Bennet had not been able to hear of his coming without changing colour. It was many months since she had mentioned his name to Elizabeth; but now, as soon as they were alone together, she said,

‘I saw you look at me today, Lizzy, when my aunt told us of the present report; and I know I appeared distressed. But don’t imagine it was from any silly cause. I was only confused for the moment, because I felt that I should be looked at. I do assure you, that the news does not affect me either with pleasure or pain. I am glad of one thing, that he comes alone; because we shall see the less of him. Not that I am afraid of myself, but I dread other people’s remarks.’

Elizabeth did not know what to make of it. Had she not seen him in Derbyshire, she might have supposed him capable of coming there with no other view than what was acknowledged; but she still thought him partial to Jane, and she wavered as to the greater probability of his coming there with his friend’s permission, or being bold enough to come without it.

‘Yet it is hard,’ she sometimes thought, ‘that this poor man cannot come to a house which he has legally hired, without raising all this speculation! I will leave him to himself.’

In spite of what her sister declared, and really believed to be her feelings in the expectation of his arrival, Elizabeth could easily perceive that her spirits were affected by it. They were more disturbed, more unequal, than she had often seen them.

The subject which had been so warmly canvassed between their parents, about a twelvemonth ago, was now brought forward again.

‘As soon as ever Mr Bingley comes, my dear,’ said Mrs Bennet, ‘you will wait on him of course.’

‘No, no. You forced me into visiting him last year, and promised, if I went to see him, he should marry one of my daughters. But it ended in nothing, and I will not be sent on a fool’s errand again.’

His wife represented to him how absolutely necessary such an attention would be from all the neighbouring gentlemen, on his returning to Netherfield.

‘’Tis an etiquette I despise,’ said he. ‘If he wants our society, let him seek it. He knows where we live. I will not spend my hours in running after my neighbours every time they go away and come back again.’

‘Well, all I know is, that it will be abominably rude if you do not wait on him. But, however, that shan’t prevent my asking him to dine here, I am determined. We must have Mrs Long and the Gouldings soon. That will make thirteen with ourselves, so there will be just room at the table for him.’

Consoled by this resolution, she was the better able to bear her husband’s incivility; though it was very mortifying to know that her neighbours might all see Mr Bingley, in consequence of it, before they did. As the day of his arrival drew near,

‘I begin to be sorry that he comes at all,’ said Jane to her sister. ‘It would be nothing: I could see him with perfect indifference, but I can hardly bear to hear it thus perpetually talked of. My mother means well; but she does not know, no one can know, how much I suffer from what she says. Happy shall I be when his stay at Netherfield is over!’

‘I wish I could say anything to comfort you,’ replied Elizabeth; ‘but it is wholly out of my power. You must feel it; and the usual satisfaction of preaching patience to a sufferer is denied me, because you have always so much.’

Mr Bingley arrived. Mrs Bennet, through the assistance of servants, contrived to have the earliest tidings of it, that the period of anxiety and fretfulness on her side might be as long as it could. She counted the days that must intervene before their invitation could be sent; hopeless of seeing him before. But on the third morning after his arrival in Hertfordshire, she saw him, from her dressing-room window, enter the paddock and ride towards the house.

Her daughters were eagerly called to partake of her joy. Jane resolutely kept her place at the table; but Elizabeth, to satisfy her mother, went to the window – she looked, – she saw Mr Darcy with him, and sat down again by her sister.

‘There is a gentleman with him, mamma,’ said Kitty; ‘who can it be?’

‘Some acquaintance or other, my dear, I suppose; I am sure I do not know.’

‘La!’ replied Kitty, ‘it looks just like that man that used to be with him before. Mr what’s-his-name. That tall, proud man.’

EXERCISE

Write a departure or an arrival scene – somebody going on a journey or a stranger coming to town.

Outsiders, outlaws and those who cross boundaries

As well as new arrivals, Jane Austen makes good use of outsiders, outlaws and people who can cross the boundaries of society. There would be many other unnamed characters too, the sort of characters that Jo Baker made such clever and interesting use of in Longbourn, which imagines the lives of those below stairs and behind the scenes in Pride and Prejudice.

In Emma (Chapter 55) we have the Gypsies who frighten Harriet Smith, Mr Perry the apothecary, and the poultry thieves whose return Emma and Mr Knightley use to hasten their nuptials.

Mrs Weston’s poultry-house was robbed one night of all her turkeys – evidently by the ingenuity of man. Other poultry-yards in the neighbourhood also suffered. – Pilfering was housebreaking to Mr Woodhouse’s fears. – He was very uneasy [. . .]

The result of this distress was, that, with a much more voluntary, cheerful consent than his daughter had ever presumed to hope for at the moment, she was able to fix her wedding-day.

Outlaws and boundary crossers may not be human. In Inga Moore’s delightful picture book, Six Dinner Sid, the actions of a boundary-crossing cat bring together the residents of a street, a group of people who have never spoken to each other before. Sid has six different names and behaves in six different ways for his six different ‘owners’4 so that he can have six different dinners every day. All is well until one day he gets a cough. The vet finds it strange that six residents of the same street have identical black cats with the same problem . . .

Think about how outsiders, outlaws and those who cross boundaries will exist in the world of your story. You can use them to deepen our understanding of the other characters and the setting, to heighten tension or to effect change. They might be foxes, cats, rats or people – perhaps somebody who sees into other people’s lives, for example a cleaner, health visitor, doctor, priest or gardener.

Write a scene that centres on the actions of a stranger, outsider, outlaw or somebody who can cross boundaries. How can the actions of a seemingly less significant character influence events in your story? How do different characters feel about and respond to the outsider or boundary-crosser? The whole plot can turn on the actions of one of these people or creatures. Write from any point of view.

Fanny Price sleeps in a little white attic at Mansfield Park. Attic bedrooms were usually occupied by servants, and readers can imagine how much grander her cousins’ bedrooms were. Fanny’s other sanctuary is the East room, a chamber that nobody else uses any more. It is described in Chapter 16.

It had been their school-room; so called till the Miss Bertrams would not allow it to be called so any longer, and inhabited as such to a later period. There Miss Lee had lived, and there they had read and written, and talked and laughed, till within the last three years, when she had quitted them. The room had then become useless, and for some time was quite deserted, except by Fanny, when she visited her plants, or wanted one of the books, which she was still glad to keep there, from the deficiency of space and accommodation in her little chamber above: but gradually, as her value for the comforts of it increased, she had added to her possessions, and spent more of her time there; and having nothing to oppose her, had so naturally and so artlessly worked herself into it, that it was now generally admitted to be hers. The East room, as it had been called ever since Maria Bertram was sixteen, was now considered Fanny’s, almost as decidedly as the white attic: the smallness of the one making the use of the other so evidently reasonable that the Miss Bertrams, with every superiority in their own apartments which their own sense of superiority could demand, were entirely approving it; and Mrs Norris, having stipulated for there never being a fire in it on Fanny’s account, was tolerably resigned to her having the use of what nobody else wanted, though the terms in which she sometimes spoke of the indulgence seemed to imply that it was the best room in the house.

The aspect was so favourable that even without a fire it was habitable in many an early spring and late autumn morning to such a willing mind as Fanny’s; and while there was a gleam of sunshine she hoped not to be driven from it entirely, even when winter came. The comfort of it in her hours of leisure was extreme. She could go there after anything unpleasant below, and find immediate consolation in some pursuit, or some train of thought at hand. Her plants, her books – of which she had been a collector from the first hour of her commanding a shilling – her writing-desk, and her works of charity and ingenuity, were all within her reach; or if indisposed for employment, if nothing but musing would do, she could scarcely see an object in that room which had not an interesting remembrance connected with it. Everything was a friend, or bore her thoughts to a friend; and though there had been sometimes much of suffering to her; though her motives had often been misunderstood, her feelings disregarded, and her comprehension undervalued; though she had known the pains of tyranny, of ridicule, and neglect, yet almost every recurrence of either had led to something consolatory: her aunt Bertram had spoken for her, or Miss Lee had been encouraging, or, what was yet more frequent or more dear, Edmund had been her champion and her friend: he had supported her cause or explained her meaning, he had told her not to cry, or had given her some proof of affection which made her tears delightful; and the whole was now so blended together, so harmonised by distance, that every former affliction had its charm. The room was most dear to her, and she would not have changed its furniture for the handsomest in the house, though what had been originally plain had suffered all the ill-usage of children; and its greatest elegancies and ornaments were a faded footstool of Julia’s work, too ill done for the drawing-room, three transparencies, made in a rage for transparencies, for the three lower panes of one window, where Tintern Abbey held its station between a cave in Italy and a moonlight lake in Cumberland, a collection of family profiles, thought unworthy of being anywhere else, over the mantelpiece, and by their side, and pinned against the wall, a small sketch of a ship sent four years ago from the Mediterranean by William, with H.M.S. Antwerp at the bottom, in letters as tall as the mainmast.

To this nest of comforts Fanny now walked down to try its influence on an agitated, doubting spirit, to see if by looking at Edmund’s profile she could catch any of his counsel, or by giving air to her geraniums she might inhale a breeze of mental strength herself.

By telling readers that it is the East room, Jane Austen ensured that we would know the sort of light and warmth that it had. Mrs Norris makes sure that Fanny doesn’t have a fire, so it would often have been chilly. Later in the novel Fanny’s uncle discovers this and sets things right. This discovery is a small incident but is significant in alerting Sir Thomas to how badly Fanny has been treated by Mrs Norris. Important scenes take place in this room, and when they do, we feel that Fanny is under attack. In Chapter 16 the theatricals which precipitate so much are only just beginning. Jane Austen doesn’t often write about particular objects, so when she does the reader takes notice. The footstool made by Julia that wouldn’t be given space anywhere else and Fanny’s geraniums add a splash of colour to the picture readers are given. We are also told, very concisely, about the objects that Fanny treasures: her books, the picture sent by William and the picture of Edmund. It’s touching that Fanny has the ‘collection of family profiles, thought unworthy of being anywhere else’. Most of these people aren’t even nice to her! I hope there wasn’t one of Mrs Norris. Fanny would probably have been too polite not to have it up with the others although hardly anybody else came into the room.

1. Light your story. Think about how your story is going to be lit. Novelists and short-story writers can learn much from filmmakers, painters and photographers here. How warm/cold/hot, bright/dim/hazy are the different places your characters inhabit? Think about indoors and outdoors. How do the lighting and temperature change during the day and according to the time of year? What will a character be able to see at night? Does light come in from the outside? What colour is it? Do street lamps or lights from other buildings shine through the windows? What are the windows like? Are they dirty or clean? What shape are they? What are the curtains or blinds like? Are there lamps, candles or mirrors? Think about the details you will use to communicate the light to the reader without writing great long passages of description. Avoid telling readers that a character wakes to see dust motes dancing in the sunbeams – editors read that too many times.

Now look back through the scenes you have written so far to see if you have lit them well. Are you consistent and do you show how places change according to the time of day or year? What colours have you told the reader about? What might particular characters coming into a room notice first? What do you want the reader to notice first? What you tell us about will depend on the point of view you are using and what you are trying to set up.

Add or subtract details to light and colour your scenes better.

2. Create rooms or private spaces for your characters. These might be places in the present time of your novel or places that characters remember; they might be bedrooms, offices, kitchens, studies, sheds or the interiors of cars. Some characters might have almost nowhere to call their own or just a locker or rucksack. Look back at the description of the East room and think about the things that each of your characters keeps in their space. Don’t forget heating and lighting but also think about smells, possible dust and grime, sounds and textures and so on. Fanny Price’s room may have smelt of her geraniums. Without a fire it would often have been very cold. What can be seen from the window(s) of your rooms? Are there secret spaces within the spaces? Use carefully chosen details. A character’s space might extend into cyberspace. What apps do they have on their phone? What do they search for on Spotify?

Create rooms or private spaces for each of your characters. These may or may not appear in your finished work, but even if they don’t this exercise will help ensure that you know your characters well.

3. Think about the writers you love and the places they were inspired by. Try to visit these places and follow in your favourite writers’ footsteps. Writers almost always use spaces they know in their work, either in totality or taking aspects of different ones to create the spaces they need. Gather photographs, maps, guidebooks, leaflets, local papers, etc.

For Jane Austen, visit Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton, Hampshire. After visiting the museum walk along the road to Chawton House Library, which was formerly one home of Edward Austen, Jane’s lucky brother, who inherited a fortune. Walking around the gardens here and at the museum will help you understand Jane’s work. Edward Austen’s other grand house, Godmersham Park in Kent, where Jane and Cassandra often stayed, is also well worth visiting, as is The Vyne, a National Trust property near Basingstoke. The Austens were friends of the Chute family, who owned it. One of the Chutes’ cousins (a poor relation) was brought to live with the family. Might this child’s story have inspired Jane? There are dozens of articles about ‘the real Pemberley’ and ‘the real Mansfield Park’, and you might also like to visit the houses they discuss.

Many of Jane’s letters were written from Godmersham. They give us useful insights into the life of the house, and it’s clear that staying there influenced her. Jane included details about particular people – for example, she knew that her father would want to know how Edward’s farming concerns were going. Jane and Cassandra had the same experience at Godmersham – visiting impecunious aunts – and Jane mentions to Cassandra how much she paid for having her hair done before a ball, an amount that shows the hairdresser was likely aware of Jane’s straitened circumstances.

Mr Hall walked off this morning to Ospringe, with no inconsiderable booty. He charged Elizabeth 5s. for every time of dressing her hair, and 5s. for every lesson to Sace, allowing nothing for the pleasures of his visit here, for meat, drink, and lodging, the benefit of country air, and the charms of Mrs Salkeld’s and Mrs Sace’s society. Towards me he was as considerate as I had hoped for from my relationship to you, charging me only 2s. 6d. for cutting my hair, though it was as thoroughly dressed after being cut for Eastwell as it had been for the Ashford assembly. He certainly respects either our youth or our poverty.5

Bath and Lyme Regis are other must-see destinations for Janeites, but don’t have the interiors that we know she inhabited, so will inspire you in different ways. The houses that we know Jane lived in or visited must have influenced her work, but we know that she also did her research, writing to Cassandra and Martha Lloyd when she was writing Mansfield Park, ‘If you could discover whether Northamptonshire is a County of Hedgerows, I should be glad again,’6 and, ‘I am obliged to you for your enquiries about Northamptonshire but do not wish you to renew them, as I am sure of getting the intelligence I want from Henry, to whom I can apply at some convenient moment “sans peur et sans reproche”.’7

Writers have to be resourceful, gleaning information where they can.