USIC MAY BE A VERY INTIMATE EXPRESSION OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE “human,” yet it is also something we share with many other animals, especially with birds and insects. While there is still some debate about to what extent the call of a thrush should be considered “music,” the designation goes far beyond being just a metaphor. The academic field of biomusicology centers on comparisons between human music and the sounds of animals. Both have similar structures, patterns, and rhythms. But these, in turn, have analogs elsewhere in the natural world such as the patterns in sedimentary rocks or the rings of trees trunks, which show a comparable blend of repetition and variation. Composers have transcribed patterns of DNA with musical notes, and found that it sounds rather like music of the Baroque period. There seems, in summary, to be something universal in music, an appeal that transcends the boundaries of species. The taste in music by other creatures varies, however, with culture. The Greeks, for example, preferred the sound of cicadas and other insects, while the British of the nineteenth century especially loved songbirds.

USIC MAY BE A VERY INTIMATE EXPRESSION OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE “human,” yet it is also something we share with many other animals, especially with birds and insects. While there is still some debate about to what extent the call of a thrush should be considered “music,” the designation goes far beyond being just a metaphor. The academic field of biomusicology centers on comparisons between human music and the sounds of animals. Both have similar structures, patterns, and rhythms. But these, in turn, have analogs elsewhere in the natural world such as the patterns in sedimentary rocks or the rings of trees trunks, which show a comparable blend of repetition and variation. Composers have transcribed patterns of DNA with musical notes, and found that it sounds rather like music of the Baroque period. There seems, in summary, to be something universal in music, an appeal that transcends the boundaries of species. The taste in music by other creatures varies, however, with culture. The Greeks, for example, preferred the sound of cicadas and other insects, while the British of the nineteenth century especially loved songbirds.

The music of whales became especially popular in the late twentieth century, but they have not been included in this chapter. Instead, they may be found in Chapter 17, “Behemoths and Leviathans,” which seemed even more appropriate.

CICADA, GRASSHOPPER, AND CRICKET

The poetry of earth is ceasing never:

On a lone winter evening, when the frost

Has wrought a silence, from the stove there shrills

The cricket’s song, in warmth unceasing ever,

And seems to one in drousiness half lost,

The grasshopper’s among some grassy hills.

—JOHN KEATS, “On the Grasshopper and the Cricket”

Entomologists place grasshoppers, locusts, mantises, and crickets in a single order, the orthoptera, while cicadas belong to the order homoptera. But modern taxonomies do not necessarily reflect popular perceptions of animals today, much less the ways in which creatures have been regarded over centuries. For the ancient Greeks, grasshoppers, locusts, crickets, and (sometimes) mantises went under the single name of “akris,” and modern translators of their works have to determine which insect seems most appropriate from the context. All of these insects were often difficult to see and were known to people primarily through their sounds in open fields. These noises, created by rubbing parts of their bodies together, are often amazingly loud for the tiny creatures that produced them, and they are often synchronized as well. They are mating calls, produced almost exclusively by males, and some ancient myths suggest a surprising awareness of this fact. In the case of orthoptera, people also knew them through the enormous damage they often did to crops, only partially compensated for by the favor these insects themselves enjoyed in culinary traditions.

The sound of the grasshopper is not particularly melodic, but it is very steady. The grasshopper provides a regular beat to accompany the singing of birds and other creatures of the field. Even today, when we have almost entirely ceased to mark dates by the behavior of wildlife, the incantation of the grasshopper still marks the beginning of autumn for many people, and the cessation of it signals the coming of winter, at which time we begin to see the bodies of perished grasshoppers along country roads. One of the most famous fables is “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” colorfully retold by the British folklorist Joseph Jacobs in The Fables of Aesop:

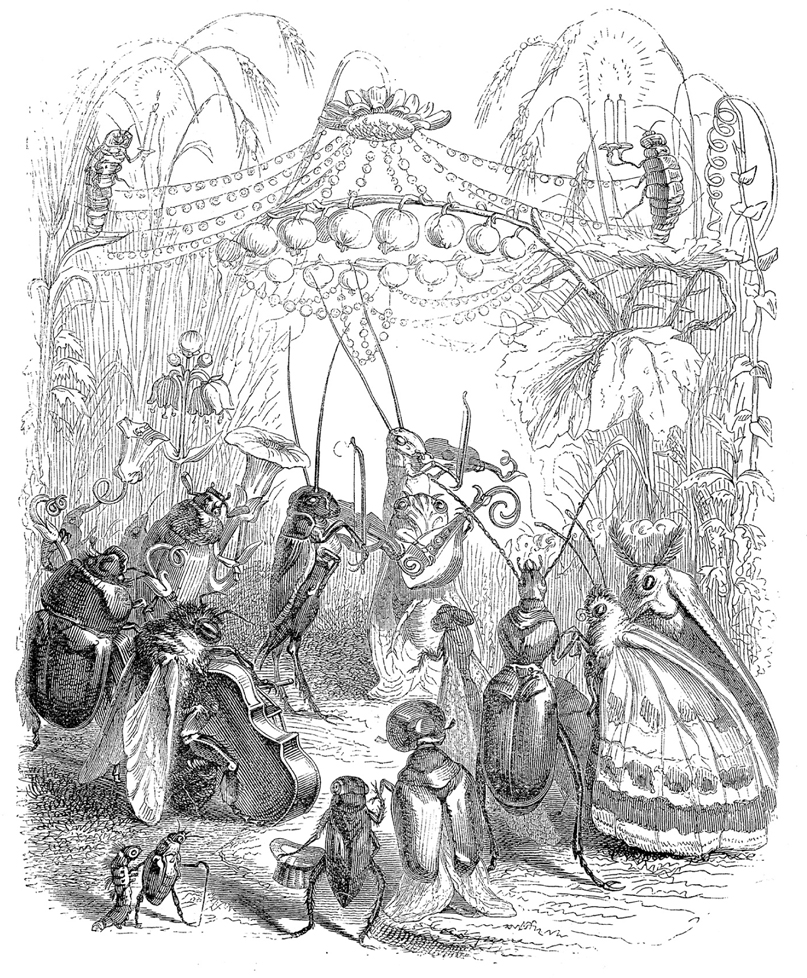

A concert of insects at a wedding party.

(J. J. Grandville, from Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux, 1842)

In a field one summer’s day, a Grasshopper was hopping about, chirping and singing to its heart’s content. An Ant passed by, bearing along with great toil an ear of corn he was taking to the nest.

“Why not come and chat with me,” said the Grasshopper, “instead of toiling and moiling in that way?”

“I am helping to lay up food for the winter,” said the Ant, “and recommend you do the same.”

“Why bother about winter?” said the Grasshopper; “we have got plenty of food at present.” But the Ant went on its way and continued its toil. When the winter came the Grasshopper had no food, and found itself dying of hunger, while it saw the ants distributing every day corn and grain from the stores they had collected in the Summer. Then the Grasshopper knew …

It is best to prepare for the days of necessity.

The contrast between the two insects is essentially that between an artist and a laborer, settled this time to the latter’s advantage.

The locust is the Mr. Hyde to the grasshopper’s Dr. Jekyll. Desert locusts usually look and behave much like grasshoppers, but in conditions of crowding and scarcity of food, they undergo a metamorphosis, changing their body color and growing larger. They also begin to reproduce more quickly and to swarm, laying waste to the surrounding countryside with incredible speed. The Bible tells us that when the Pharaoh refused to let the people of Israel leave Egypt, locusts were the eighth plague sent by Yahweh in punishment:

The locusts invaded the whole land of Egypt. On the whole territory of Egypt they fell, in numbers so great that such swarms had never been seen before, nor would be again. They covered the surface of the soil till the ground was black with them. They devoured all the green stuff in the land and all the fruit of the trees

(Exodus 10:14-15).

In North Africa and the Near East, plagues of locusts have continued to occur into the twentieth-first century, sometimes darkening the sky and confirming the general accuracy of the Biblical descriptions. In similarly vivid terms, the prophet Joel compared locusts in their vast numbers and their destructiveness to an invading army. The same imagery was used by the Egyptians themselves, and in an inscription commemorating the deeds of Ramesses II— according to some traditions the very Pharaoh who was confronted by Moses— at the battle of Kadesh; it reports that the armies of the Hittites covered the mountains like locusts. For all the trouble they caused, however, the Egyptians do not seem to have hated or despised such insects, and one text from the Old Kingdom speaks of a ruler ascending to heaven in the form of a grasshopper.

In an Islamic folktale from Algeria, the Devil looked scornfully on the newly created world and said, “I can do better than God.” “Very well,” replied God, “I will give you the power to bring to life whatever creature you create. Stroll about the world and return in a hundred years.” The Devil took up the challenge and put together a creature with the head of a horse, the breast of a lion, the horns of an antelope, the neck of a steer, and parts from several other animals. Since the parts did not fit properly, he began to whittle away at the creature, until only a tiny locust was left. The Lord says, “Oh, Satan … What is this! To show your impotence and my power I will send swarms of this creature around the earth, and thus I will teach people that there is only one God.”

Perhaps because locusts in the Bible were always a scourge of God, the insects themselves have usually not been heavily stigmatized. People will hardly ever eat creatures that they find repugnant, except in times of severe hunger, but locusts and grasshoppers are eaten in much of Africa. They are also mentioned as a possible food in the Bible (Leviticus 11:20-23).

In ancient Egypt, the grasshopper was a popular motif, often depicted on festive items cosmetic boxes or jewelry. The prophet Isaiah said of Yahweh, “He lives above the circle of the earth; its inhabitants look like grasshoppers” (Isaiah 11:24). These insects have continued to be used as symbols of insignificance, in ways that may be either endearing or contemptuous. It is possible to see a bit of each response in the Greek myth of Tithonus, a prince of Troy, who was loved by Eos, goddess of dawn. The deity asked Zeus to grant her lover immortality, but she forgot to ask for eternal youth for him as well. As he grew old, she left him, and eventually he withered away and became a grasshopper.

The repeated sounds of crickets have not always impressed Westerners as unequivocally beautiful or cheerful. In Germany, somebody with a neurotic obsession is said to have crickets in his head. On the other hand, repetitions can represent the sometimes irritating yet essential lessons of conscience. One variety is known as the “house cricket” for its habit of frequently entering homes. Because these crickets are drawn to warmth, they are symbols of the hearth. To have such a visitor is traditionally considered good luck throughout Europe, and killing it can bring ill fortune. The Chinese, however, value crickets for their martial spirit, and gladiatorial combats between crickets have been a popular sport in China since ancient times.

In Carlo Collodi’s classic for children Pinocchio (1883), the hero, a wooden puppet that has come to life, smashes a cricket named Jiminy with a mallet but, after many misfortunes, regrets his evil deed. Disney Studios later made Jiminy Cricket into one of their most popular animated characters, and even had him introduce the television show Walt Disney Presents.

Cicadas, especially, are generally known only through their sound, since they dwell in trees and are usually not seen until they die and fall to the ground. For the Greeks, they seemed to be incorporeal beings and symbolized immortality. In Plato’s dialogue “Phaedrus,” Socrates and the young man Phaedrus had been engaged in a passionate discussion of philosophy, and the former remarked that the cicadas, while singing and conversing among each other, must surely also be observing their dialogue. He went on to explain that these insects were once human beings. When the Muses first came to earth, bringing with them music and the other arts, a few people were so thrilled with their new gifts that they would do nothing except sing, quite forgetting to eat and drink. After a while, they died happily, thinking only of their art. They returned to life as cicadas, creatures to which the Muses have granted the boon of never needing any earthly sustenance. They sing from their moment of birth onwards, without food or drink, until the day of their death, after which they go and report about human beings to the Muses, telling who has honored the arts and their divine patrons. Socrates assured his young pupil that the two of them might expect a good report from the cicadas, since they had been discoursing on the theme of love.

These insects have traditionally had a similar meaning among the Chinese, who also believed that cicadas lived only on dew. From the late Chou through the Han dynasties (ca. 200 BCE through ca. 220 CE), the Chinese would place jade cicadas in the mouths of their dead to insure immortality. For cultures of the Far East, the songs of insects such as cicadas and crickets also represent the chanting of Buddhist priests. They are sometimes kept in cages, and their songs are often considered more beautiful than those of birds.

CUCKOO, LARK, NIGHTINGALE, AND WOODPECKER

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon a midnight with no pain,

While thou are pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain—

To thy high requiem become a sod.

—JOHN KEATS, “Ode to a Nightingale”

Before the modern era, the sounds of nature were everywhere, day and night. Buildings, even Medieval castles with walls thick enough to resist sieges, were not built to keep them out. The sounds of birds, most especially, were used to mark both the hours of the day and the seasons. The cuckoo is the bird of spring, while the lark sings at early morning, and the nightingale during the night. This gave them significance at once practical and poetic, as is illustrated by this exchange from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, taking place after a night of love:

JULIET:

Wilt thou be gone? it is not yet near day;

It was the nightingale, and not the lark,

That pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear;

Nightly she sings on yon pomegranate tree:

Believe me, love, it was the nightingale.

ROMEO:

It was the lark, herald of the morn,

No nightingale.

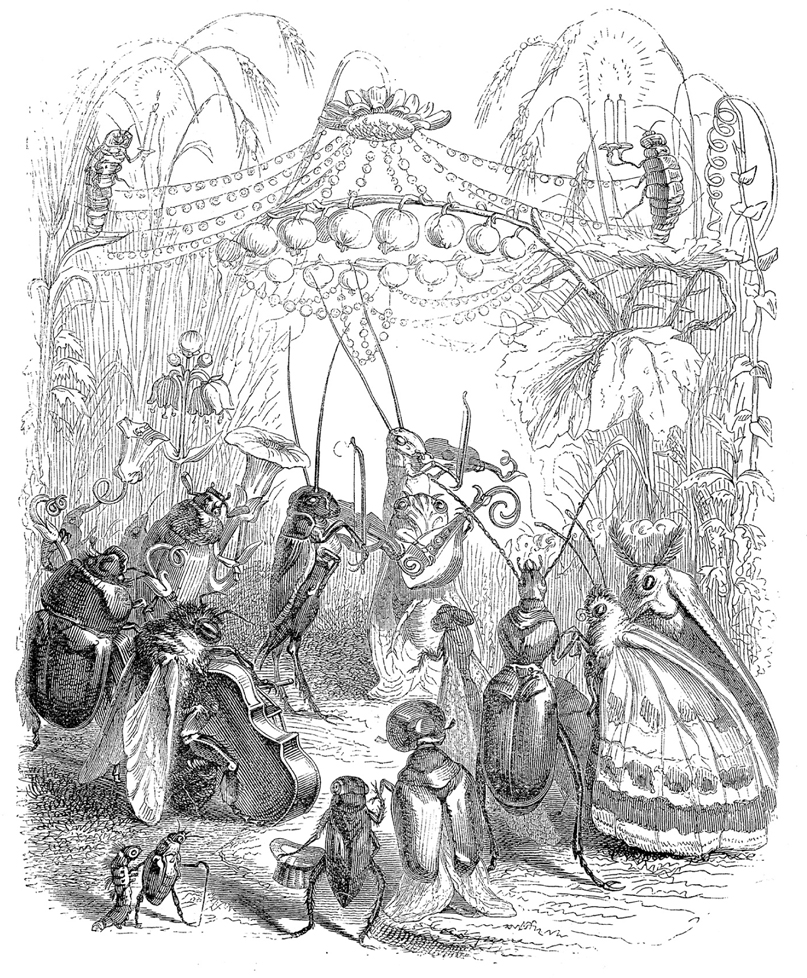

While the nightingale proclaims his love, the rose cavorts with a dirty beetle.

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville, from Les Animaux, 1868)

These two birds were constantly used to signal the time of day and night. The association of birdsong with hours is why many of the first affordable clocks used a mechanical cuckoo to announce the time.

The song of the cuckoo traditionally announces the beginning of summer with an outpouring of exuberant energy. Farmers understood it as a signal to begin planting, but spring is above all the season of love. Through most of history, apart from the High Middle Ages and the nineteenth century, amorous passion has been regarded with suspicion, and that may also be said of the cuckoo. Its song has been traditionally a good omen to those who planned to marry, but also a warning of possible adultery to those already wedded.

Pliny the Elder suggested that hawks transformed themselves into cuckoos, since the hawks seemed to vanish at about the same time cuckoos became numerous. He observed, however, that hawks would eat cuckoos if they did meet. The idea reflected the cuckoo’s reputation for treachery, since, as Pliny put it, “the cuckoo is the only one of all the birds that is killed by its own kind.” This superstition continued into the twentieth century in parts of Europe.

According to one myth, Zeus first made love to Hera after he had moved her to pity by appearing in the form of a disheveled little cuckoo. The bird was an attribute of Hera and adorned her scepter. Indian poets knew the cuckoo as the “ravisher of the heart,” and the god Indra also assumed the form of a cuckoo for the purpose of seduction.

The idea that the cuckoo is an adulterer has at least some distorted basis in observation, since the European cuckoo will lay its eggs in the nest of another bird. The egg containing the young cuckoo will generally hatch first, and the fledgling will push the other eggs from the nest. Pliny explained this by saying that all other birds so hated the cuckoo that they dared not make nests, for then they would be vulnerable to attack. The only way the cuckoo can procreate is by concealing the identity of its offspring.

The use of the word “cuckold”—derived from the Old French “cocu,” meaning “cuckoo”—for a man whose wife is unfaithful goes back at least to the late Middle Ages. Shakespeare wrote in his play Love’s Labor’s Lost:

When daisies pied, and violets blue,

And lady-smocks all silver hue,

Do paint the meadows with delight,

The cuckoo then on every tree

Mocks married men; for thus sings he,

“Cuckoo;

Cuckoo, cuckoo” O word of fear,

Unpleasing to the married ear!

In an era when marriage for love was still a somewhat revolutionary idea, the cuckoo increasingly came to represent sexual desire, while the nightingale signified romantic love.

While the cuckoo of literature is masculine, the nightingale is usually female in Western culture, and people have found her song less exuberant than sweet or sad. Her tragedy, as told by Apollodorus, began when Procne, a princess of Athens, married King Tereus of Thrace, and they had a son named Itys. Tereus raped Philomela, Procne’s sister, and then cut out the tongue of the victim so she would not reveal his crime. Philomela wove a tapestry depicting the deed, made the cloth into a robe, and gave it to Procne, who then killed Itys, boiled him, and served his son up to Tereus in revenge. When the King realized what had happened, he set out in pursuit of the two sisters. The women prayed to the gods, who then turned Procne into a nightingale, Philomela into a swallow, and Tereus into a hoopoe. Later Latin authors, however, confused the two sisters and called the nightingale “Philomela,” a name afterwards used by poets throughout Europe, perhaps because the song of a nightingale seemed less that of a killer than that of an innocent victim. According to Pliny the Elder, their song was so beloved in Rome that caged nightingales in Rome commanded the sort of prices usually paid for slaves.

In traditions of the Near East, the nightingale is masculine and in love with the rose, a tragic passion incapable of consummation, but the Islamic world shared Western ambivalence about romantic passions. In The Conference of Birds, written by Sufi poet Farid Ud-Din Attar in Persia around the end of the twelfth century, the hoopoe summoned the birds to a pilgrimage to their king, the simorgh. The nightingale answered that roses flowered only for him, and so he could not leave even for a single day. The hoopoe replied that the love of the rose was a superficial illusion, and that the rose really mocked the nightingale by fading in a day.

In the tenth-century Arabic fable The Island of Animals, however, the nightingale proved to be the most eloquent and sensible of the animals. He surpassed even such fine speakers as the jackal and the bee, as the beasts brought suit for mistreatment against people before the King of the Jinni. When a man from Mecca and Modena argued that human beings were especially favored by God, the nightingale carried the day by replying that human beings therefore had a special responsibility not to abuse other creatures.

In Russia, by contrast, nightingales were often associated with witchcraft. There was a great demand for caged nightingales to sing in the homes of aristocrats and wealthy merchants. Peasants hired to capture the birds would have to wander about the woods at night following the sound, and they often feared becoming victims of enchantment. In Russian folklore, “Nightingale” was a monstrous bird-man who was half bird, nested in oak trees, lay in wait for travelers on the road to Kiev, and could whistle up a wind strong enough to kill human beings.

The lark begins to sing at early morning before the sun has even risen, and so it has been associated with beginnings. In “The Birds” by the Greek comic playwright Aristophanes, the lark boasts that it is not only older than the gods but the very earth itself, an idea perhaps inspired by the ability of the lark to sing in flight. When its father died, there was no ground, so the lark had to bury him in its own head.

As with so many other things, people tend not to appreciate animals until they begin to disappear. As Europe industrialized and many birds became less common, romantic poets of the nineteenth century celebrated their songs with perhaps unprecedented intensity. The singing of birds represented a sort of poetic inspiration that was utterly natural and spontaneous. Among the most famous lyrics of the period were “Ode to a Nightingale” by Keats and “To a Skylark” by Shelley, in which the poets long to enter the world of joy that could inspire the songs of a bird. Hans Christian Andersen celebrated the beauty of nature over the creations of humankind in “The Emperor’s Nightingale,” which tells of a mechanical bird that fails to sing as sweetly as one in the wild.

An elegiac poem, which perhaps marks the end of this tradition, is “the Darkling Thrush” by Thomas Hardy, published in the first years of the twentieth century, which ends:

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the glowing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed hope whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

As the twentieth century progressed, writers increasingly understood references to nightingales or larks as part of outmoded poetic diction.

The woodpecker is not a singer so much as a musician, but its sound announces the start of the rainy season in many cultures. The sound of a woodpecker knocking its beak against a tree is like a martial drum and resonates loudly through the forest. The woodpecker was sacred to Ares, Greek god of war. Romulus and Remus, the legendary twins who founded Rome, were suckled by a wolf and fed by a woodpecker. Ovid wrote in Metamorphoses that the witch Circe changed a young man named Picus, son of the Roman god Saturn, into a woodpecker after he had refused her advances.

As more of a fighter than a lover, the woodpecker has never been terribly popular, yet it may do better than songbirds in fitting the raucous popular culture of the latter twentieth century. One of the most popular cartoon characters of the mid-twentieth century was the violent, and frequently amoral, trickster Woody Woodpecker.

In recent decades, the ivory-billed woodpecker, which was once common in the forests and swamps of the Southeastern United States, has attained an iconic status. Due primarily to loss of habitat, it probably became extinct in the latter twentieth century, yet there are still occasional reports of possible sightings, and some birders have made finding it into almost a mystic quest.

USIC MAY BE A VERY INTIMATE EXPRESSION OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE “human,” yet it is also something we share with many other animals, especially with birds and insects. While there is still some debate about to what extent the call of a thrush should be considered “music,” the designation goes far beyond being just a metaphor. The academic field of biomusicology centers on comparisons between human music and the sounds of animals. Both have similar structures, patterns, and rhythms. But these, in turn, have analogs elsewhere in the natural world such as the patterns in sedimentary rocks or the rings of trees trunks, which show a comparable blend of repetition and variation. Composers have transcribed patterns of DNA with musical notes, and found that it sounds rather like music of the Baroque period. There seems, in summary, to be something universal in music, an appeal that transcends the boundaries of species. The taste in music by other creatures varies, however, with culture. The Greeks, for example, preferred the sound of cicadas and other insects, while the British of the nineteenth century especially loved songbirds.

USIC MAY BE A VERY INTIMATE EXPRESSION OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE “human,” yet it is also something we share with many other animals, especially with birds and insects. While there is still some debate about to what extent the call of a thrush should be considered “music,” the designation goes far beyond being just a metaphor. The academic field of biomusicology centers on comparisons between human music and the sounds of animals. Both have similar structures, patterns, and rhythms. But these, in turn, have analogs elsewhere in the natural world such as the patterns in sedimentary rocks or the rings of trees trunks, which show a comparable blend of repetition and variation. Composers have transcribed patterns of DNA with musical notes, and found that it sounds rather like music of the Baroque period. There seems, in summary, to be something universal in music, an appeal that transcends the boundaries of species. The taste in music by other creatures varies, however, with culture. The Greeks, for example, preferred the sound of cicadas and other insects, while the British of the nineteenth century especially loved songbirds.