RADITIONS RUNNING FROM THE LEGENDARY AESOP TO CHAUCER AND beyond make the barnyard a place of merriment and adventure. At least by comparison with their twenty-first century counterparts, the animals in those barnyards seem a lot more “wild” than “domestic.” Death by human hands remains largely impersonal, since, for the animals, human beings are largely avatars of fate. Until the time for that has come, the denizens of the barnyard must constantly match their wits against foxes and other predators. The fence separating the barnyard from adjacent forests and fields is the final boundary between civilization and the wild, and so farm animals are, in many ways, the first line of defense. Though they will kill and eat the animals in time, farmers are very protective of them; the predations of carnivores can arouse a truly furious human response. Animals of the barnyard are especially stylized to reflect mores of human society. The rooster is a protective head of the household, while the hens are very maternal. As we approach contemporary times, however, the freedom of barnyard animals gradually diminishes. In E. B. White’s novella Charlotte’s Web (1952), they continue to have lively adventures, though these are shadowed by a constant awareness of mortality. In George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), from the same era, however, the barnyard becomes a metaphor for the totalitarian state. In the twenty-first century, people are reviving the practice of raising animals, especially chickens, in suburban and yards and even on urban rooftops.

RADITIONS RUNNING FROM THE LEGENDARY AESOP TO CHAUCER AND beyond make the barnyard a place of merriment and adventure. At least by comparison with their twenty-first century counterparts, the animals in those barnyards seem a lot more “wild” than “domestic.” Death by human hands remains largely impersonal, since, for the animals, human beings are largely avatars of fate. Until the time for that has come, the denizens of the barnyard must constantly match their wits against foxes and other predators. The fence separating the barnyard from adjacent forests and fields is the final boundary between civilization and the wild, and so farm animals are, in many ways, the first line of defense. Though they will kill and eat the animals in time, farmers are very protective of them; the predations of carnivores can arouse a truly furious human response. Animals of the barnyard are especially stylized to reflect mores of human society. The rooster is a protective head of the household, while the hens are very maternal. As we approach contemporary times, however, the freedom of barnyard animals gradually diminishes. In E. B. White’s novella Charlotte’s Web (1952), they continue to have lively adventures, though these are shadowed by a constant awareness of mortality. In George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), from the same era, however, the barnyard becomes a metaphor for the totalitarian state. In the twenty-first century, people are reviving the practice of raising animals, especially chickens, in suburban and yards and even on urban rooftops.

BULL AND COW

Man in his prosperity forfeits intelligence.

He is the one with the cattle doomed to slaughter.

—PSALMS 49:20

Bulls and cows already are prominent in the Paleolithic paintings on the walls of caves in France, Spain, and other parts of Europe. In the main chamber of the cave at Lascaux, five enormous bulls decorate the ceiling. In the homes of Çatal Huyuk (near Jericho, in Turkey), are many shrines to bulls from the middle of the ninth millennium BCE. Large bulls’ heads of modeled in clay extend from the walls. Similar shrines to bulls have been found in much of the Mediterranean area. Only very slowly did people lose their fear of these giants. Cattle were not domesticated until around 3,000 BCE in Europe, long after other animals such as the dog, sheep, and goat.

There is a very intimate association of man and bull in the religion of Zoroaster, where sacred texts tell that Ohrmazd made a lone white bull, “shining like the moon,” as the fifth act of creation. He then made the first man Gayomart, as the sixth. The seed of man and bull were then created from “light and the freshness of sky,” so that both would have abundant progeny. As the world draws to an end, Soshyant, a descendant of Zoroaster, is to sacrifice a great bull named Hadhayans, and its fat will be used to make the elixir of eternal life.

As the largest of domestic animals, the bull was the supreme sacrificial offering throughout almost all of the ancient Mediterranean. The skin, bones, gristle, and a small bit of meat were left on the altar for a god, while people feasted on the rest. Some, however, thought it impious to give the gods such a tiny share. On important occasions, the Hebrews would perform a “holocaust,” a sacrifice in which the entire animal was offered up to God. The Bible gives a very detailed description of the bull sacrifice that accompanied the investiture of priests. Some blood was placed around the bull’s horns by the altar to purify it, and the rest was poured out onto the ground. Every part is of the bull was disposed of according to a precise ritual (Leviticus 8:14-17).

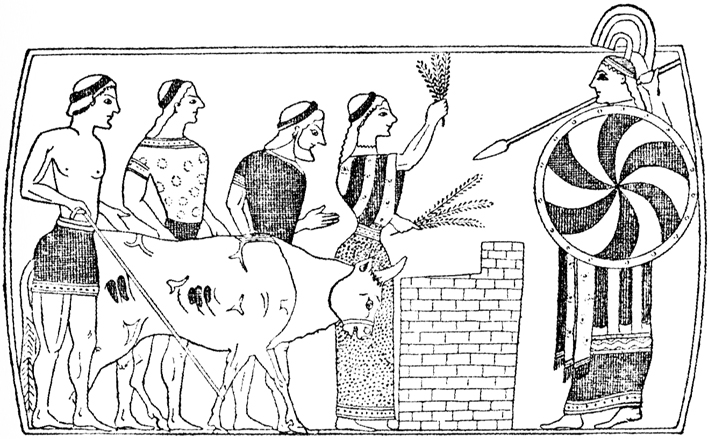

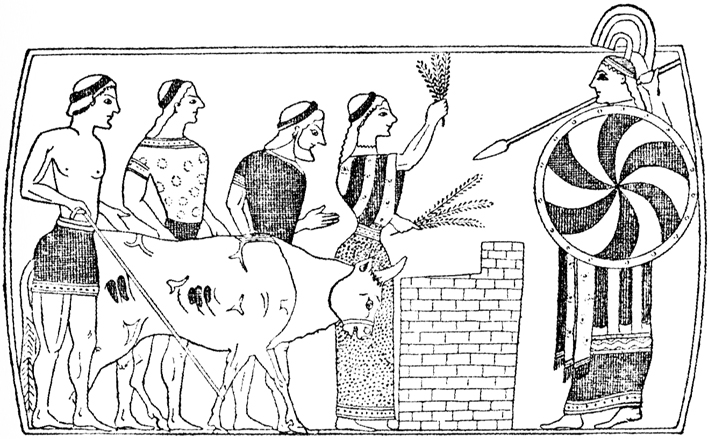

Greek painting of a bull being led to the altar for slaughter.

In Greece the sacrifice of a bull was generally reserved for Zeus, in Rome for his counterpart, Jupiter. The slaying of the bull became the central rite in the religion of Mithras, which rivaled Christianity in popularity during the latter part of the Roman Empire. Mithras, accompanied by a dog and other animals, would plunge his sword into a great bull at the end of the world, so that all things might live again. Artists of the Roman Empire would show grain sprouting from the wounds of the bull as it was slain by Mithras.

In one myth of the Greeks, Poseidon, god of the sea, had given King Minos of Crete an enormous bull, intending that Minos should offer it back as a sacrifice, but Minos kept the bull for himself instead. This act, a possible allusion to the first domestication of animals, began a sequence of events in which great buildings were erected, unnatural acts performed, and people sacrificed. The angry god caused the king’s wife, Pasiphaë, to fall in love with the bull. She ordered Daedalus, the great inventor, to construct a hollow cow of wood, and she crept inside. From there, she made love to the bull and conceived the minotaur, a monster with the head of a bull and the body of a man. Deeply ashamed, Minos ordered Daedalus to construct a labyrinth, an underground series of passageways, to house the minotaur. When his son Androgeos was killed by Athenians, Minos demanded that the Athenians send a tribute of seven youths and seven maidens every year as penance. The young people were placed in the labyrinth, where they wandered until they were either eaten by the monster or else died of hunger themselves. Theseus, a prince of Athens, volunteered to go as one of the youths. Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, fell in love with him. She gave him a ball of yarn to unroll as he wandered through the minotaur, as well as a sword to do battle with the creature. Theseus killed the minotaur, returned to the entrance following the trail of yarn, and escaped Crete with Ariadne.

The tale mocks the rulers and the religion, especially fertility rites, of the Cretans, often adversaries of the Greeks. Minos, a fool and tyrant in Greek mythology, appears to have been an actual ruler in Crete. He claimed the bull as an ancestor, and he did indeed have an elaborate palace with underground chambers at Knossos. The minotaur was a Cretan god, whom the Greeks considered a grotesque, unnatural creature. He anticipated the Christian devil with his horns and his dwelling beneath the ground.

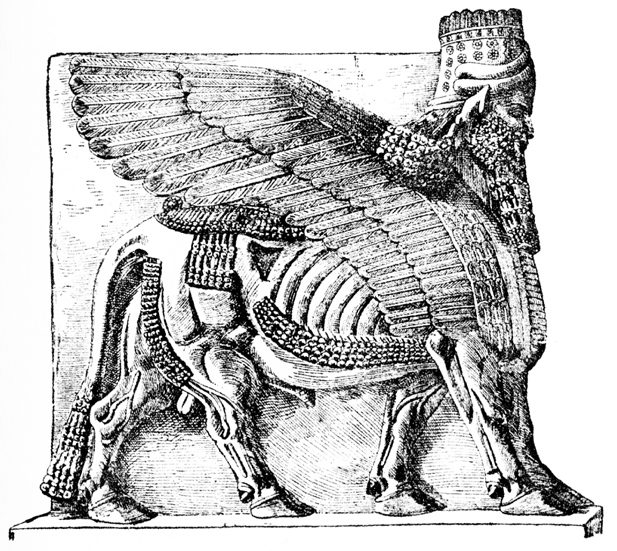

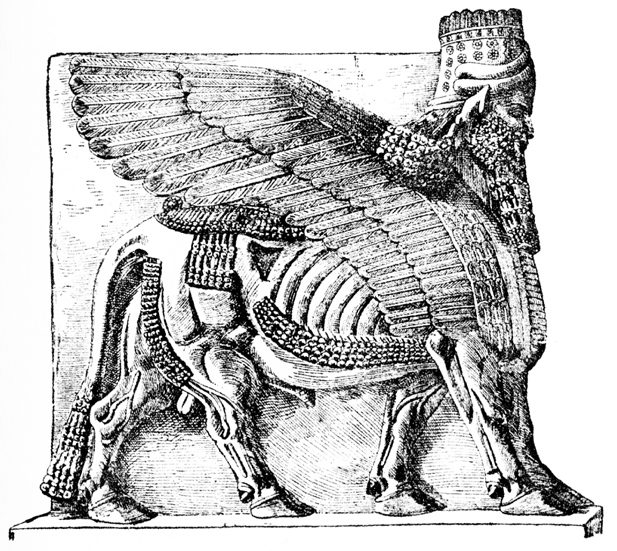

Ancient Cretan wall paintings showed acrobats turning somersaults on the back of a bull. In the Mesopotamian tale of Gilgamesh, our earliest heroic epic, the bull of heaven represents a terrible drought, which came early in the second millennium and may have destroyed the mighty Akkadian Empire. The bull was sent down to earth as a punishment because Gilgamesh and his companion Enkidu had cut down the cedar forests of Lebanon and killed their guardian, Humbaba. The bull of beaven immediately killed hundreds of people. Enkidu grabbed the horns of the bull and leapt aside, and then Gilgamesh killed the bull with his sword. Despite this tale, the worship of the bull persisted in Mesopotamia, where people identified it with Anu, the god of the sky, and Adad, the god of storms. There are a number of depictions of bull-men in Mesopotamian art, and scholars speculate that some may represent Enkidu.

In Egypt, the Apis bull was considered an incarnation of the creator god Ptah, conceived when fire came down from heaven and impregnated a cow. Priests identified this bull by searching among calves for one with very specific markings. He would be black, but with an inverted white triangle on his brow. A mark shaped like the silhouette of a vulture stretched across his shoulders, and there would be a crescent moon on his sides. He would also possess a sign like a beetle on his tongue. Once the Apis bull was found, there would be great rejoicing. He would march in a great procession; women would pray to him for children, and priests would perform sacred rites. Finally, he would be brought to the temple of Ptah, where he would live. When he finally died, the bull would be consecrated to Osiris, god of the dead, and buried in great splendor. Then priests would search for his successor.

Assyrian winged bull from the palace of Sargon

The Greeks and Romans, who had anthropomorphic deities, sometimes thought the animal-gods of Egypt were strange or primitive. Nevertheless, they generally respected the Apis bull. Herodotus told how Cambyses, King of the Persians, committed a sacrilege against Apis. After conquering Egypt, Cambyses arrogantly threw his dagger at the sacred bull, striking the animal in the thigh. Then Cambyses ordered the priests of Apis to be beaten and forbade them to celebrate any festivals under penalty of death. The Apis bull died unattended in the temple and was secretly buried. Shortly afterwards, the gods struck Cambyses with madness. He killed his brother, sister, and many trusted servants in fits of temper. Finally, after he had driven his subjects to revolt, Cambyses accidentally wounded himself in the thigh with his own sword. When he realized that the place of the wound corresponded exactly to that where he had struck the Apis bull, the horrified Cambyses knew that he was doomed. The wounded limb became infected with gangrene and he died shortly afterwards.

Illustration by Albrecht Dürer to Sebastian Brandt’s Ship of Fools (1494), showing worship of the golden calf.

The golden calf, which the Israelites worshipped on the flight from Egypt, is a form of the Apis bull. The Hebrews were constantly struggling with the old animal cults, and Moses put this one down with great ruthlessness, killing about 2,000 people. Today, bullfights reenact the struggle against the ancient cult of the bull. It is remarkable that, with all the power of our technology, we still need such ritual affirmations of human dominance.

The many deities of the ancient world who were depicted in the form of a bull also included the Greek Dionysus, Phoenician Moloch, and the Syrian Attis. Siva, the Hindu god of creativity, rides on a white bull, and so the cow and bull are sacred in much of India. The cow and bull were also important in the culture of the Far East, but there they have been viewed with a bit less awe and more intimacy. The ox is a sign in the Chinese zodiac. The sage Lao Tzu has often been depicted riding on a water buffalo, and so are small boys playing the flute. Cattle in Asia are not only admired but often loved as well.

With many animals such as the cat and dog, worship eventually led to domestication. In a similar way, religious awe can evolve into economic power. The value of coins, initially, was measured according to the animals they might buy, and the earliest coins are stamped with pictures of cattle. In Homeric times, a coin known as “a talent of gold” was the equivalent of an ox. Our word “pecuniary” comes from the Latin “pecus,” meaning “domestic herd animal.” Expressions such as the “growth” of investments also hark back to a time when herds and flocks were the major measure of wealth.

It is strange that English has no common word that can stand for either “bull” or “cow” in the singular. The closest, perhaps, is “bovine” which sounds a bit pedantic. When we speak of a “rabbit” or a “spider,” the subject may be either female or male. For the cow and bull, however, sexuality is such an intimate part of their identity that, apparently, even the word cannot dispense with gender. The same is true in other languages such as Latin. Both bull and cow are extremely important in the religious history of humanity, but their symbolism is so different that they sometimes hardly seem to be of the same species. As we have seen, the bull is generally associated with generative power and energy. The cow is, by contrast, maternal.

The cow has often been worshipped as a provider of milk, and, unlike the bull, she was seldom sacrificed. In Norse mythology, the creation of the world begins when the cow Audhumbla was created from melting frost. She nourished the giant Ymir with rivers of milk. For nourishment, Audhumbla licked salt on ice of the frozen waste, gradually uncovering a human figure—Buri, ancestor of the gods.

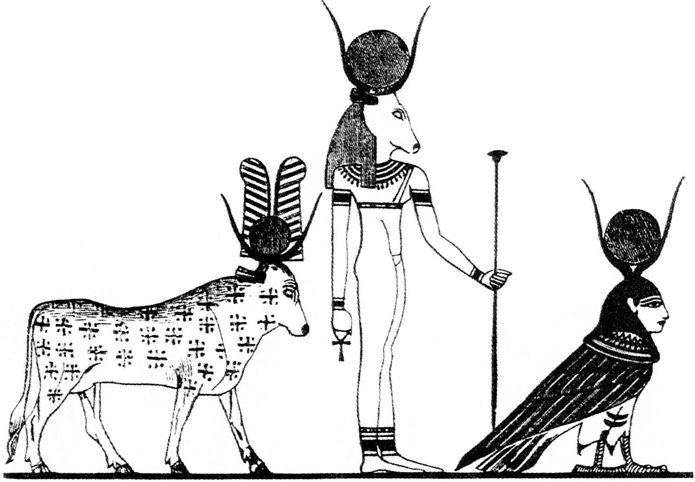

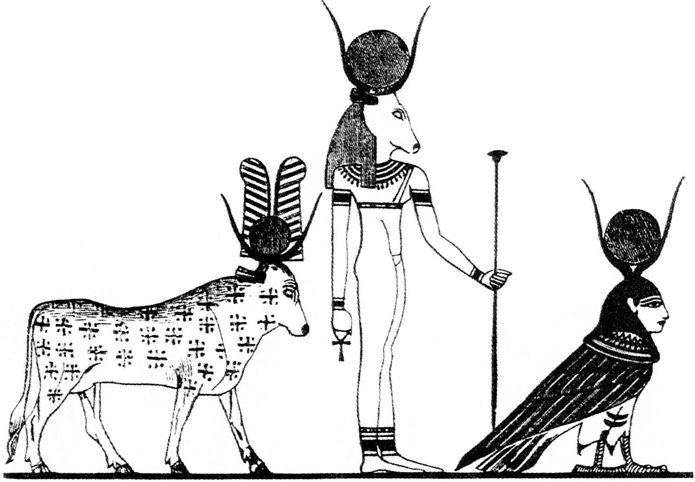

The Egyptian goddess Hathor, mistress of the underworld, was often depicted in the form of a cow. As goddess of love, music, and fertility, she was among the most beloved of deities, though she could become vengeful and extremely dangerous. In Greek mythology, Hera, the wife of Zeus, is referred to as “cow-eyed” by Homer, and may have been a bovine deity in very remote times. Her husband Zeus constantly had affairs with mortals. In one tale, Hera surprised Zeus when he was making love to the maiden Io. Hoping to cover up his transgression, Zeus turned Io into a heifer. Hera saw through the trick, and sent a fly to torment the transformed maiden, driving the poor victim all over the world.

Hollow images of cows inside of which people might be buried were made in Egypt and elsewhere in the ancient world. Herodotus told how the daughter of the pharaoh Mycerinus, in her last moments, asked her father if she might still see the sun once a year. Devastated by her death, Mycerinus ordered a large cow to be made of wood, hollowed out, and covered up with gold. A golden orb representing the sun was then placed between the horns, and the young woman was buried in the cow. Lamps were kept always burning beside the cow, and once a year the cow was raised and exposed to the light of day.

What is greatly valued easily becomes an object of contention. Cattle raids were frequent and might even lead to wars. In Greek mythology, the infant Hermes, who later became messenger of the gods, stole the cattle of the sun god Apollo. He killed two and locked the rest in a cave. After eating them, he strung the guts of the cattle across a tortoise shell to make the first stringed instrument, a lyre. Apollo, who could tell the future, easily found the thief. The mother of Hermes protested that her son was but an infant and certainly not capable of theft, but Apollo demanded that his property be returned. Finally, Apollo exchanged the cattle for the lyre and thus became the patron of music. At the time, wealth was measured far more often in the form of cattle than of money. For the very rich, from ancient Greece to the present, wealth has often been measured by possession of art, and tycoons such as Mellon, Carnegie, Morgan, Rockefeller, and Getty have often been avid collectors. The story of the trade between Hermes and Apollo contrasts these two forms of wealth, the more tangible form of livestock and the more spiritual one of art.

Some of the forms taken by the Egyptian cow-goddess Hathor.

Perhaps the most important epic of the Celtic people is the Tain Bo Cuailnge or “Cattle Raid of Cooley.” As it begins, Queen Maeve and her husband Ailill were arguing about which of them brought greater wealth to their marriage. They compared their goods, which included clothes, jewels, and sheep. Maeve was able to match every possession of Ailill except for a white horned bull named Fennbhennach. There was only one other bull so fine in all of Ireland, a bull named Donn Cuailnge in the province of Ulster. Queen Maeve resolved to have that bull, and, when it was refused to her, she sent an army to steal it. The hero Cu Cuchulainn valiantly defended Ulster, but after many battles, Maeve finally carried off her prize. The story ended with a fight between the two bulls, and Donn Cuailinge was victorious. It wandered about with the entrails of Fennbhennach on his horns, and then finally died of its wounds. The story is not altogether unlike many American westerns, once as popular as cheap paperbacks and early television shows, in which “cattle rustlin’” often ignites a “range war.”

Even after millennia of domestication, cattle have not entirely lost their numinous quality. Those who are associated with cattle seem to gain some of their power and virility, at least in popular imagination. This is so for the heroes of ancient epics as well as the gauchos of Argentina and the cowboys of the American West. Eating beef is still associated with strength and virility, so muscular men are referred to as “beefcake.”

Ancestral patterns can be very persistent, even when the culture no longer appears to sanction them. Despite the Christian ban on animal sacrifice, Medieval bestiaries often saw a symbol of Christ in the ox or bull that is slain for food. In 1522, desperate to stop the black plague, Pope Leo X allowed bulls to be sacrificed in the Old Roman Coliseum, though to no avail. On farms in England, sacrifices of bulls have been practiced from time to time, sometimes even in the twentieth century CE, for such purposes as stopping disease or witchcraft. The bulls have sometimes been killed in very brutal ways, such as being buried upside down or burned alive, when people thought that was what the magic required.

When Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had a son, later to become Philip II of Spain, he celebrated by publicly killing a bull in the marketplace. The most notable survival of animal sacrifice may be in the bullfights of the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America. The popularity of bullfighting began at start of the modern era, around the sixteenth century CE. The elaborate ceremony and pageantry now associated with bullfighting date only from the late 1800s. The bull is systematically enraged by being kept in darkness, and then abruptly exposed to the bright lights of the arena. Lancers on horseback systematically goad the bull, then, when the animal has been worn out, the matador delivers the fatal thrust with his sword. The triumph of the matador’s finesse and skill over brute power symbolizes the victory of “civilization” over “barbarism.” Despite the obvious cruelty, matadors insist that they respect and even love the bulls. On a barely conscious level, the appeal of the bullfight may, like archaic sacrifices, be based on the expectation that death can release cosmic energy, which then nourishes all of life.

COCK AND HEN

It faded on the crowing of the cock.

Some say that ever, ‘gainst that season comes

Wherein our Savior’s birth is celebrated,

This bird of dawning singeth all night long;

And then, they say, no spirit dare stir abroad,

The nights are wholesome, then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallow’d and so gracious is the time.

— WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Hamlet act 1, scene 1

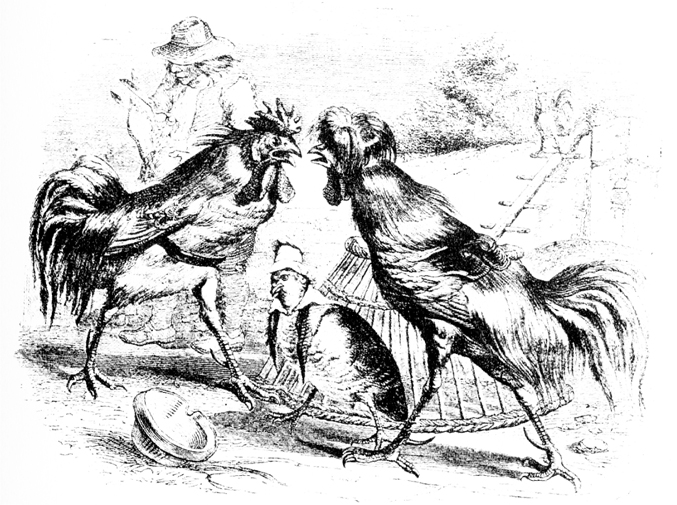

Aelian wrote, in the second century CE, of two Greek temples separated by a river, one consecrated to Hercules and the other to his wife, Hebe. Cocks were kept in the temple of the god and hens in that of the goddess. The roosters would cross the waters once a year to mate, returning with any male offspring and leaving the females for the hens to raise. The arrangement is not very plausible, among other reasons because cocks generally cannot stay together without fighting, and so barnyards have only a single rooster per flock. Nevertheless, the account shows how cock and hen, even more than other animals, seem to be defined by their gender, to a point where they hardly appear to belong to a single species. Both cock and hen were indeed kept for sacrifice in temples throughout the ancient world from Egypt to Greece. On the altars, their entrails were used to predict the future.

Two cocks fighting over a hen.

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville-from Fables de la Fontaine, 1839)

Until recent times, even urban dwellers would generally be woken by the call of a rooster at dawn. From ancient times through much of the Middle Ages, the crowing of the cock at certain times was so predictable that it was used to signal the changing of the guard. It had a triumphant ring, and was said to frighten away the spirits of darkness. The crowing of a cock served as the voice of conscience in the Bible after Peter had denied knowing Jesus, since the sound moved him to tears of regret (Matthew 26:75). The red comb of a cock heightened its association with the sun. Roosters themselves have always been celebrated for their fierceness, as they seemed to lord over the barnyard.

The cock is also a solar animal in East Asia, where it is the tenth sign of the Chinese zodiac. According to one Japanese tale, the sun-goddess Amaterasu, angry at the violence of the storm-god, moodily withdrew into a cave, leaving the world in darkness. When a cock crowed, she wondered if the dawn had come without her and went to the entrance of her cavern, to see that indeed it was bright day.

Hens, by contrast, are symbols of domesticity and maternal care. Especially when brooding on their eggs, they seem unconcerned about all else, even the cock. In the Bible, Jesus says, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem … How often have I longed to gather your children, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, and you refused!” (Matthew 23:37).

Long before Christ, the cock symbolized resurrection. The cock was associated with Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, who as a mortal physician once raised a man from the dead. The last words of Socrates, as recorded in Plato’s dialogue “Phaedo,” are, “Crito, we ought to offer a cock to Asclepius. See to it and don’t forget.” Perhaps Socrates wished to thank the god for spiritual healing as he moved on to the next world.

Because cockfighting is extremely ancient, widespread, and practiced virtually wherever roosters are found, many anthropologists believe that the birds were initially domesticated for the sport rather than for meat. Their willingness to fight one another to the death has made cocks a symbol of the warrior spirit. Before such battles as Marathon and Salamis, Greek commanders would rouse their men to battle by showing them fighting cocks. The general Themistocles ordered an annual cockfight in Athens to commemorate the victory of the Greek over the Persians. Fighting cocks might also be used to predict the outcome of a battle. In the Medieval Japanese Tale of the Heike, a local warlord uses a cockfight to decide which side to take in the war between the Heike and Genji clans. He matched seven cocks that were white, the color of the Genji, against seven that were red, the color of the Heike. When all of the white cocks had proved victorious, he knew that the Genji would also win.

At the start of the seventeenth century, the naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi of Bologna wrote of two friends that sat down to eat a roasted rooster. When one casually remarked that even Christ could not raise the bird from the dead, the cock immediately leapt up, splashing the men with sauce, and then turned them into lepers. In a version of the story from Ireland, a group of unbelievers was sitting around a fire over which a cock had been boiled. “We have buried Christ now,” said one “and he has no more power to rise from the dead than the cock in this pot.” Immediately, the cock rose and crowed three times, saying, “The Virgin’s son is saved.” Versions of the story are set to music in “King Pharim” and other Christmas carols.

The cock also experiences a sort of resurrection in a famous story from the work of Alcuin, a learned monk at the court of Charlemagne. A rooster, boasting of his powers, forgot to remain watchful and suddenly found the jaws of a wolf had closed about his neck. The cock begged to hear the wolf sing just once, so he would not have to die without hearing the wonderful harmonies of a lupine voice. The wolf opened his mouth to grant the request, at which the cock immediately flew up to a tree and admonished the wolf, saying. “… Whoever is taken in by false pride will go without food …” For some Medieval readers, the jaws of the wolf represented the grave or, perhaps, the gate of Hell, and the bird was saved not only by his cleverness but also by grace. In later versions, the adversary of the cock was usually the fox, and the story—essentially a variant of Aesop’s fable of “The Fox and the Crow”—has been retold by Marie de France, and countless other fabulists from the Middle Ages till the present.

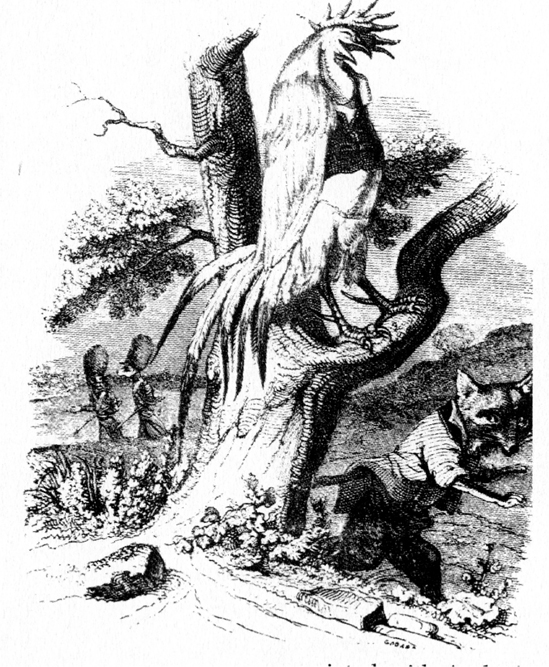

The cock outsmarts the fox in this medieval fable, retold by La Fontaine.

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville-from Fables de la Fontaine, 1839)

The gently ironic version of the story by Geoffrey Chaucer in his Canterbury Tales, written in the late fourteenth century, elaborates the simple fable by adding heraldic symbolism and, with it, all of the pageantry of late Medieval courtly life. The cock, Chauntecleer, becomes a noble knight with seven hens as mistresses, one of which, Pertelote, has the special status of a full wife. They all speak in relatively formal verse, quoting not only the Bible but also classical authors such as Cicero and Cato, but, in the end, Chauntecleer is saved not by learning but by his quick wit. As Chaucer recognized, the moral that one should not trust flattery applies especially to powerful lords and ladies.

The use of the rooster as a symbol of France dates back at least to Medieval times, but it only became popular around 1789 during the French Revolution. This symbolism ultimately derives from a play on the Latin word “gallus,” which can mean both rooster and Gaul. The Revolutionaries wished to break with their Royalist and Christian traditions, and the new French Republic was intended to be a “resurrection” of the nation’s “gallic” past.

Since the cock and hen are so quintessentially male and female, people have often viewed any violation of their sexual roles as foolishness or worse. Using reasoning not entirely unlike that of modern sociobiologists, people in earlier eras often sought, in observation of animals, a sanction for customs such as female subordination. In the eighteenth-century Chinese novel The Story of the Stone, the aristocratic Lady Wang gently advises younger women to resigned acceptance of fate, quoting an “old rhyme”:

When rooster crows at break of day,

All his hen-folk must obey.

According to a traditional belief that has been found from Germany to Persia, a hen that crows like a cock augurs terrible fortune and has to be killed immediately. A number of cocks were judicially condemned to death in the Middle Ages for laying eggs. Writing around the end of the twelfth century, Alexander of Neckam stated that an egg laid by an old cock and incubated by a toad could produce a cockatrice, a serpent able to kill with a glance.

Today, the proud society of the barnyard has largely disappeared, and most people rarely see fowl before it reaches the supermarket or the dinner plate, though heraldic roosters still decorate packages of cereal and many other products. Cock fighting is now illegal in the United States and most of Europe, but people, particularly from Latin America or the Caribbean, still practice it, believing they are preserving the values of a more heroic age.

GOAT AND SHEEP

I am not certain that anyone who has not spent time with shepherds can appreciate the intense involvement that exists between the shepherd and his flocks. The wellbeing of the flock is all, and everything else falls by the wayside. All that is done the whole year long is attuned to the single overriding consideration of the flock. Man’s fierceness in defending his flocks and his lack of tolerance for anything he even imagines impinging on them are remarkable. To people who keep sheep, it almost seems, every other animal on earth could perish and it would be of no account.

—ROGER CARAS, A Perfect Harmony

Sheep and goats were, together with the dog, the first animals to be domesticated by human beings, around the end of the last ice age. Over the millennia, the symbolism and patterns of behavior these animals inspired have been especially intimately integrated into human culture. Sheep and goats are perhaps the only animals that have created not only an industry but also an entire way of life. Pastoral peoples must traditionally center almost every activity around their flocks, staying in one place for a time and then migrating when the edible vegetation is exhausted. Flocks inspire intense protectiveness, and they compel herders to constantly view predators such as wolves and even neighboring people as possible threats. By moving in unison and following a leader, sheep especially provide a model for understanding human society.

Sheep also provide wool, for clothing, and food. They will generally eat little besides grass, but they may be kept in rough, mountainous areas that are unsuitable for farming. Goats provide less meat, but they give copious quantities of milk. What is more, they can eat almost anything that grows, and they are even able to climb trees in order to get at their leaves. Tending flocks offered the most peaceful means to financial advancement in the relatively static societies of the ancient world, so shepherds were perhaps the first middle class.

The Biblical story of Cain and Abel records an early conflict between nomadic herders and settled agriculturists. Abel the shepherd offered the first born of his flock to God, while Cain the farmer offered his produce. God looked with favor only on the sacrifice of sheep. Consequently, Cain killed his brother (Genesis 4:1-8), perhaps as a human sacrifice. Since herding requires a larger area of land than farming, growing population density gradually forced more people to turn to agriculture. Nevertheless, the vocation of shepherd remained an honored one in the ancient world, especially among urban dwellers who felt nostalgic for a simpler past. It offered many opportunities for solitude and contemplation. The Greek mythologist Hesiod tells in Theogony how he first became a poet when the Muses appeared to him as he tended sheep on the slopes of Mount Helicon.

God looking with favor on the sacrifice of Abel while Cain looks on in anger.

(Illustration from the mid-nineteenth century by Julius Schnorr Carolsfeld)

The Egyptian god Amun was often portrayed with the head of a ram. The Greeks identified Amun with Zeus, who, they believed, had taken the form of a ram when the gods temporarily fled to Egypt in their war with the Titans. To commemorate his escape, Zeus later placed the ram in the zodiac, where it became the constellation Aries. Zeus was also identified with a domestic herd animal in his own right. When the goddess Rhea, his mother, hid the infant Zeus on the island of Crete to escape the wrath of his father Cronos, the fairy goat Amalthea suckled him. Later one horn of Amalthea broke off, and Zeus turned it into the cornucopia or “horn of plenty.”

Perhaps because they seem to integrate themselves so well into otherwise forbidding landscapes, the Greeks constantly associated sheep and goats with flight and hiding. Odysseus, according to Homer, hid himself from the cyclops Polyphemus by clinging to the wool on the belly of a sheep. When their wicked stepmother had arranged to sacrifice the children Phrixos and Helle, a golden ram sent by Zeus swooped down from the sky, and carried them away on its back. Helle fell into the sea, but Phrixos was taken to Colchis, where he sacrificed the ram. Its golden fleece was placed upon a tree and guarded by a dragon, until it was stolen by the hero Jason, assisted by the princess Medea, and today it is used to symbolize the goal of a mystic quest.

The Hebrews were largely a nation of herders, and many patriarchs of Israel including Abraham, Moses, Jacob, and David tended flocks. Abraham was commanded by God to sacrifice his son Isaac, but was stopped at the last moment by an angel, who directed him to a ram struggling in the bushes, which he was to kill in place of the boy (Genesis 22). The story is usually interpreted as a test of faith, though some thinkers also see it as a rejection of human sacrifice. At any rate, it illustrates the close identification, almost to the point of being interchangeable, between Israel and a flock. Jewish legend tells that Moses tended flocks for 40 years, not allowing a single sheep to be hurt by wild beasts or lost. As a reward for his care, God made Moses the leader of Israel.

When Moses had placed a curse on Egypt that the first born in every home would be slain, Yahweh directed that every Hebrew household sacrifice a one-year-old male sheep or goat without blemish and smear some of the blood on the doorposts or lintel, so that Israel might be spared (Exodus 12). The Jews commemorate this event in spring during the feast of Passover, at which a lamb is eaten with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. The Last Supper of Christ, commemorated in the mass, was probably a Passover meal. In contemporary America, Easter dinner still often features roast lamb.

The one other herd animal that, though unnamed, has had a comparable role in the religious history of humanity is the scapegoat. In a passage from Leviticus, Aaron was directed to take two goats, one of which was to be sacrificed to Yahweh and the other, the scapegoat, driven into the desert for the demon Azazel (Exodus 16:7-10). This event probably reflected a residual paganism among the Hebrews, which was very promptly repudiated. A later passage in Leviticus states of the Hebrews, “They must no longer offer their sacrifices to the satyrs (i.e., goats and associated deities) in whose service they once prostituted themselves” (Exodus 17:7). The goat consecrated to Azazel has become a symbol of all that are made to suffer for the sins of the community, such as the Jews in Nazi Germany.

Both the Old and New Testaments also constantly used metaphors drawn from herding to speak of religious matters. Psalm 23, known as “The Lord’s Prayer,” begins

Yahweh is my shepherd

I lack nothing.

In the meadows of green grass he lets me lie.

To the waters of repose he leads me;

There he revives my soul (1-3).

When John the Baptist first saw Jesus, he exclaimed, “Look, there is the lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world” (John 1:29). Jesus also compared God to a good shepherd (John 10), and the metaphor is commemorated in a bishop’s crosier, a ceremonial shepherd’s crook. In Revelations, the “Lamb” is used as a code word for Christ, who is to return for a final battle against the forces of evil. Matthew compared the Last Judgment to a shepherd separating the sheep from the goats (Matthew 25:32-33).

The growing antipathy toward goats in the Judeo-Christian tradition was in reaction to their veneration in other cultures of the ancient world. The Greek god Dionysus took the form of a goat when fleeing to Egypt to escape the serpent Typhon. A goat was sacrificed at the annual festival of Dionysus, in a ceremony from which Greek tragic drama eventually emerged.

According to some myths, the nature spirit Pan was the offspring of the god Hermes and a goat. For other figures of the Greek pantheon, he was a sort of country bumpkin. They banished Pan from Mount Olympus for his ugliness, and so he wandered the fields and forests. When fleeing from the serpent Typhon, he tried to turn himself into a fish but was so terrified that he could not complete the transformation. He is pictured in the zodiac as a goat with the tail of a fish, the sign Capricorn, and the tale is the origin of the word “panic.” Pan himself could inspire terror, the dreadful solitude of remote places, in any traveler who disturbed his mid-day sleep. The Greco-Roman satyrs, his woodland companions, had human bodies with only the ears and sometimes horns of a goat. They were often depicted pursuing nymphs, usually without much success, and they were lecherous enough to mate with animals as well.

The Greek Historian Herodotus reported that the Egyptians considered “Pan” (that is, their god Khem) the most ancient of their gods. He also claimed that in Egyptian province of Mendes, people venerated goats, especially the males, and held goatherds in great honor. To the historian’s revulsion, the people of that town reportedly allowed a woman to publicly mate with a goat.

Two magical goats, which could be sacrificed, eaten, and then resurrected, accompanied the Norse god Thor. In Northern Europe, goats were admired less for their fecundity than for their ability to thrive in severe, mountainous landscapes. In the Middle Ages, however, painters often depicted the Devil with the horns of a goat.

To summarize so far, sheep and goats were increasingly used throughout the ancient world to express various polarities: sheep were generally thought of as feminine, goats as masculine; sheep were civilized, goats natural; sheep were Judeo-Christian, goats, pagan. This basic symbolism changed very little throughout the Middle Ages and the modern world, but the way in which these various qualities were valued varied greatly. In the eighteenth century, bucolic poetry often nostalgically celebrated the simple shepherd tending his flock. Among romantics of the nineteenth century, who were fascinated by the idea of primeval wildness, the goat-god Pan became by far the most popular figure in the Greco-Roman pantheon. It was a rather ironic choice, since goats actually do prodigious damage to forests by nibbling at young trees. But, as in so many other contexts from hunting to exploration, people often seem to celebrate the natural world most when engaged in destroying it.

In contrast with the West, the Chinese have never made such a great symbolic distinction between sheep and goats; in fact, the two are often interchangeable. Sheep were introduced in East Asia later than goats, and the two herd animals have often been pictured grazing together in oriental art. The eighth sign of the Chinese zodiac may be depicted as either a goat or ram. The goat, with its preference for remote solitary places, can often represent the anchorite, and the beard of a male goat resembles that often depicted on a Chinese sage. The half-legendary Huang Ch’u P’ing, who lived in the fourth century CE, was a goatherd who decided to withdraw from the world. He had meditated for forty years when his brother found him in a cave. After greeting him, the brother asked what had become of the goats. Huang Ch’u P’ing pointed to a several white stones which lay scattered around the cavern, and he began to touch them, one by one, with his staff, at which each rock jumped up and became a goat.

RADITIONS RUNNING FROM THE LEGENDARY AESOP TO CHAUCER AND beyond make the barnyard a place of merriment and adventure. At least by comparison with their twenty-first century counterparts, the animals in those barnyards seem a lot more “wild” than “domestic.” Death by human hands remains largely impersonal, since, for the animals, human beings are largely avatars of fate. Until the time for that has come, the denizens of the barnyard must constantly match their wits against foxes and other predators. The fence separating the barnyard from adjacent forests and fields is the final boundary between civilization and the wild, and so farm animals are, in many ways, the first line of defense. Though they will kill and eat the animals in time, farmers are very protective of them; the predations of carnivores can arouse a truly furious human response. Animals of the barnyard are especially stylized to reflect mores of human society. The rooster is a protective head of the household, while the hens are very maternal. As we approach contemporary times, however, the freedom of barnyard animals gradually diminishes. In E. B. White’s novella Charlotte’s Web (1952), they continue to have lively adventures, though these are shadowed by a constant awareness of mortality. In George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), from the same era, however, the barnyard becomes a metaphor for the totalitarian state. In the twenty-first century, people are reviving the practice of raising animals, especially chickens, in suburban and yards and even on urban rooftops.

RADITIONS RUNNING FROM THE LEGENDARY AESOP TO CHAUCER AND beyond make the barnyard a place of merriment and adventure. At least by comparison with their twenty-first century counterparts, the animals in those barnyards seem a lot more “wild” than “domestic.” Death by human hands remains largely impersonal, since, for the animals, human beings are largely avatars of fate. Until the time for that has come, the denizens of the barnyard must constantly match their wits against foxes and other predators. The fence separating the barnyard from adjacent forests and fields is the final boundary between civilization and the wild, and so farm animals are, in many ways, the first line of defense. Though they will kill and eat the animals in time, farmers are very protective of them; the predations of carnivores can arouse a truly furious human response. Animals of the barnyard are especially stylized to reflect mores of human society. The rooster is a protective head of the household, while the hens are very maternal. As we approach contemporary times, however, the freedom of barnyard animals gradually diminishes. In E. B. White’s novella Charlotte’s Web (1952), they continue to have lively adventures, though these are shadowed by a constant awareness of mortality. In George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), from the same era, however, the barnyard becomes a metaphor for the totalitarian state. In the twenty-first century, people are reviving the practice of raising animals, especially chickens, in suburban and yards and even on urban rooftops.