ETS—ANIMALS KEPT IN THE HOME SOLELY TO OFFER COMPANIONSHIP to people—are largely a phenomenon of modern Western culture. Prior to that, animals were often kept in or near human dwellings, and intense bonds developed between them and people, though they almost always had either a religious or pragmatic purpose. In Rome, people would sometimes keep a snake in their home, believing it to be the spirit of an ancestor, a practice that survived into modern times in parts of Italy and Eastern Europe. Caged birds were also kept, largely to provide music. In the Middle Ages, aristocrats often kept dogs for hunting or to guard the home. Cats, as well as dogs, were used for catching mice. Hawks were used to catch rabbits and other small game. Paradoxically, as such purposes have been increasingly taken over by mechanical devices, the ownership of pets has soared. The Humane Society of the United States estimates that in 2011 39% of American households had at least one dog, while 33% had at least one cat. To some extent, these animals may serve as mediators with the natural world. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, dogs especially have been so completely integrated into human society that it is questionable how much they can still serve that purpose. They no longer have their own detached “doghouses,” but live in the home, where they are elaborately trained, fed prepared foods, and seldom allowed to run freely. Today, advertisements and popular articles often refer to people with companion animals not as “owners” but as “pet parents,” while the pets themselves are called “boys” and “girls.” In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, scholars have increasingly recognized the novelty of modern pet-keeping, and a vast academic literature has accumulated around the study of the relationships between pets and human beings. Scholars sometimes prefer the term “companion species,” coined by Donna Haraway, since it embraces not only contemporary pet-keeping, but also its many precedents in the co-evolution of animals and humans.

ETS—ANIMALS KEPT IN THE HOME SOLELY TO OFFER COMPANIONSHIP to people—are largely a phenomenon of modern Western culture. Prior to that, animals were often kept in or near human dwellings, and intense bonds developed between them and people, though they almost always had either a religious or pragmatic purpose. In Rome, people would sometimes keep a snake in their home, believing it to be the spirit of an ancestor, a practice that survived into modern times in parts of Italy and Eastern Europe. Caged birds were also kept, largely to provide music. In the Middle Ages, aristocrats often kept dogs for hunting or to guard the home. Cats, as well as dogs, were used for catching mice. Hawks were used to catch rabbits and other small game. Paradoxically, as such purposes have been increasingly taken over by mechanical devices, the ownership of pets has soared. The Humane Society of the United States estimates that in 2011 39% of American households had at least one dog, while 33% had at least one cat. To some extent, these animals may serve as mediators with the natural world. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, dogs especially have been so completely integrated into human society that it is questionable how much they can still serve that purpose. They no longer have their own detached “doghouses,” but live in the home, where they are elaborately trained, fed prepared foods, and seldom allowed to run freely. Today, advertisements and popular articles often refer to people with companion animals not as “owners” but as “pet parents,” while the pets themselves are called “boys” and “girls.” In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, scholars have increasingly recognized the novelty of modern pet-keeping, and a vast academic literature has accumulated around the study of the relationships between pets and human beings. Scholars sometimes prefer the term “companion species,” coined by Donna Haraway, since it embraces not only contemporary pet-keeping, but also its many precedents in the co-evolution of animals and humans.

CAT

The cat is the only animal to have succeeded in domesticating man.

—MARCEL MAUSS

“When I play with my cat, who knows but that she regards me more as a plaything than I do her?” wrote Michel de Montaigne in “Apology for Raymond Sebond.” Touch or pet a cat and there may be sparks! Cats are constantly rubbing their backs against any available surface, so static electricity builds up in their fur. People have always been mystified by the ability of cats to survive after falling from tall trees or buildings. No wonder cats have always seemed magical. The enormous eyes of a cat shine with special intensity when the rest of its body is shrouded in darkness. Because the pupils of the cat constantly expand and contract to adjust to the level of light, they seem like the waxing and waning moon.

In many ways, cats may be subordinate to the master or mistress of the house, but their manner always suggests confidence and power. Jean Cocteau called the cat “the soul of a home made visible.” The intense attachment that cats develop to their homes seems, at least in the context of most traditional cultures, feminine. The troubled partnership of cat and dog in many human homes often resembles that of women and men. We can also think of the cat within the home as the secret wildness in every person that survives despite the regimentation of our public lives. The self-assured bearing of cats suggests hidden knowledge, which people have both valued and feared.

The curvilinear design of the feline body and the cat’s rhythmic way of walking are also classically feminine. Many archaic goddesses were closely associated with cats. The Greek Artemis, goddess of the moon, fled to Egypt and changed herself into a cat to escape the serpent Typhon. A panther was sacred to the goddess Astarte, the Mesopotamian equivalent of Aphrodite, who was often portrayed standing upright on her mascot. The Hindu goddess of birth, Shasti, also used a cat as her mount. Freya, the Norse goddess of love, rode in a chariot drawn by cats.

Perhaps most importantly, the Egyptian goddess Bastet was depicted with the head of a cat and the body of a woman. Our word “puss” or “pussy” for cat comes from Pasht, an alternative name for Bastet. The yearly festival of Bastet, held in autumn, was the most splendid celebration in all of Egypt. Hundreds of thousands of people would come on boats, singing and clapping to the music of castanets. They would offer sacrifices at the temple of Bastet, then feast for several days.

The Egyptians punished the unsanctioned killing of a cat with death. Diodorus Siculus reported that in the middle of the first century BCE a member of a Roman delegation to Alexandria accidentally killed a cat. A crowd stormed his house. Not even the fear of Roman anger could keep the local citizens from killing the perpetrator. Several superstitions about cats may go back to ancient Egypt, and many people still say that killing a cat brings bad luck.

According to Herodotus, the entire family in an Egyptian home would go into mourning when a cat died. All members would shave their eyebrows to show their sorrow. Dead cats were taken to the city of Bubastis, where they were embalmed and ceremoniously buried. Hundreds of thousands of mummified remains of cats have been found in Egyptian tombs.

A fable known as “The Cat Maiden,” traditionally attributed to the Greek Aesop, records the triumph of feminine wiles over masculine strength, which is clear in this retelling by the British folklorist Joseph Jacobs:

The gods and goddesses were arguing about whether it was possible for a thing to change its nature. “For me, nothing is impossible,” said Zeus, the god of thunder. “Watch, and I will prove it.” With that, he picked up a mangy alley cat, changed it into a lovely young girl, had her dressed in fine clothes, instructed her in manners, and arranged for her to be married the next day. The gods and goddesses looked on invisibly at the wedding feast. “See how beautiful she is, how appropriately she behaves,” said Zeus proudly. “Who could ever guess that only yesterday she was a cat!” “Just a moment,” said Aphrodite, the goddess of love. With that, she let loose a mouse. The maiden immediately pounced on the mouse and began tearing it apart with her teeth.

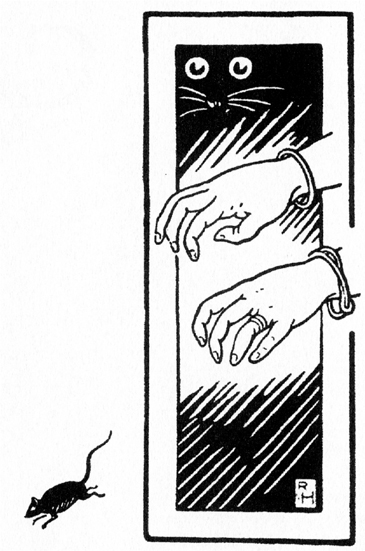

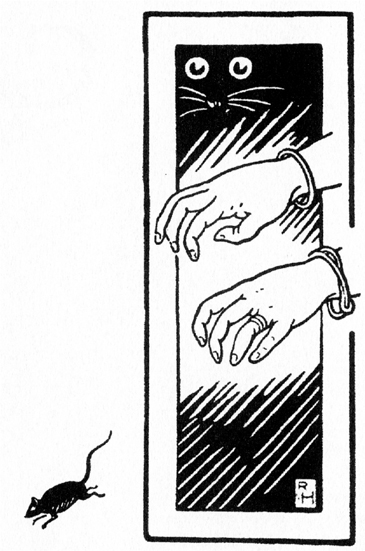

Illustration by Richard Heighway to Aesop’s fable, “The Cat Maiden.”

This fable has been written down in many versions, some of which date back to the fifth century BCE in Greece.

“Dick Whittington and His Cat,” a tale from Medieval England, shows how cats were valued in the early modern period by those engaged in trade. The hero, Dick Whittington, was an impoverished young man in London who had worked hard and managed to buy a cat, which he lent to a ship’s captain. The captain sold the cat for a vast fortune to the king of the Moors, whose palace was plagued by rats. Whittington became a wealthy man and, eventually, Lord Mayor of London in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, though the tale was not written down until much later.

Aboard ships, cats were kept as mascots and served to catch mice. Virtually all mariners were male, and they sometimes believed that the presence of a woman on board, or even the mention of a woman’s name, would bring ill luck. The cat, often the only female on the ship, was a mediator with the feminine powers of the weather and the sea. Mariners predicted the weather by watching the cat. When the cat washed its face, they would expect rain. When the cat was frisky, they would expect strong winds. Cats would also know if the ship was about to sink. Every detail of the cat’s behavior would be closely scrutinized for portents.

Superstitions about cats are almost as diverse as they are numerous. A black cat, for example, is usually thought of as a sign of bad luck, while a white cat means good luck. Sometimes, however, especially in England, this has been reversed. Wives of mariners in England would keep black cats as a charm for the safe return of their husbands at sea, a practice that people in other communities could misinterpret as witchcraft.

In Renaissance Europe, cats were often thought to be the familiars of witches, and black cats in particular were frequently named as such in the witch trials. Jean Boille, who was burned as a sorceress at Vesoul in 1620, claimed to have seen demons and cats participating together in sexual orgies at the witches’ Sabbath. A pact with the Devil was sealed with a paw print placed on the body of a witch. The Black Witch of Fraddan flew through the air at night on an enormous cat. In the early thirteenth century, the bishop of Paris, Guillaume d’Auvergne, claimed that Satan appeared to his followers in the form of a black cat and they had to kiss him beneath the tail.

Diabolic, and sometimes almost as frightening as the Devil himself, is the King of the Cats in Irish folklore. Sometimes the King is black and wears a silver chain, but he cannot always be recognized. Lady Wilde in Legends of Ancient Ireland tells of a man who once, in a fit of temper, cut off the head of a domestic cat and threw it into a fire. The eyes of the cat continued to glare at him from within the flames, and the feline voice swore revenge. A short time later the man was playing with a pet kitten; suddenly the kitten lunged, bit his throat, and killed him.

When people are fond of certain animals, they assume the animals will also be beloved by the gods and goddesses, and they offer them up as sacrifices. The ancient Egyptians may have punished the killing of a cat outside of a temple with death, but they offered thousands of cats to Bastet, generally by breaking their necks. Christianity officially rejected animal sacrifice, but ritual killing of cats continued for thousands of years. Cats were burned alive on Ash Wednesday in Metz and other Continental cities during the Middle Ages to produce ash needed for the mass. In England, the effigy of Guy Fawkes that was ceremonially burned every year sometimes contained a cat that would howl as the flames rose. Remains of cats that were walled up alive have been found in the foundations of several Medieval buildings, including the Tower of London. This was the theme of Edgar Allan Poe’s famous horror story “The Black Cat.” Terrified that his wife was a witch, and that her black cat was the Devil, the narrator killed his wife and built a wall to conceal her body, but the cat howled from behind the wall until the police came.

Toward the end of the Middle Ages, there were few cats left in Europe. Their absence led to a great increase in rats and murine diseases, most notably bubonic plague. The few cats that had survived the persecutions came to be highly valued. Europeans realized that cats were not only useful but also loyal and affectionate, and thus benevolent cats began to appear in fairy tales, though they still usually seemed to have something a little disturbing about them. In “The White Cat” by Madame D’Aulnoy, a magical feline guided the hero through all sorts of trials and tribulations. Finally, the cat cast off its skin, became a woman, and married him. She then burned the skin; after all, would the man really want his wife changing shape and casting spells? Perhaps the magic here is the power of young love, a kind of sorcery that needs to put away as a person enters maturity.

In “Puss in Boots” by Charles Perrault, a cat loyally helped a young man. To win a fortune for him, however, the two had to connive and deceive everybody else. Master Puss made up a title, “the Marquis of Carrabas,” for the young man. Then the cat told harvesters that they would be chopped up into little pieces if they didn’t tell the king their land belonged to that Marquis. When challenged by the cat to display his prowess in shape-shifting, the ogre, who really owned the land in question, transformed himself into a mouse. The cat immediately pounced on the mouse, ate him, and took over the ogre’s castle for the young man. Finally, the young man had so much wealth that he could marry the king’s daughter. If the story were told from another point of view—say, that of the ogre—the reader could easily take this cat for the Devil. Still, it is great having such a cat on your side!

In folklore, the animals in a household often make up their own little society, a sort of microcosm. The dog, of course, is among the most domesticated of animals, while the rodents are completely wild. The cat is in between. The folkloric dog and cat are constantly quarreling and making up. Sometimes they cooperate to help their master, but the old enmity can break out at any time. The cat and mouse, by contrast, are mortal enemies. The mice in the household hardly ever defeat the cat, though they often manage to get away. The situation is a bit like a troubled family of human beings, where mother and father quarrel, and the children suffer.

Buddhists generally dislike the cat, though they have seldom carried this to the extremes we find in the West. The Jatakas, ancient Buddhist fables describing how the animals assembled around the deathbed of Buddha to pay him homage, note that the cat was taking a nap and didn’t come. According to another traditional tale, the goddess Maya sent a rat with medicine for the ailing Buddha, but the cat killed the rat, so Buddha perished. Nevertheless, cats were regularly kept as mousers in households of China, Japan, and other countries of the Far East. Artists were often fascinated by their alertness, as well as by their sensitivity to subtle sounds and motions. For such a common animal, cats were notably absent from the Chinese zodiac, in part because they were closely associated with the element of earth.

For all their differences, Christianity and Buddhism have both tended to be suspicious of archaic magic. Perhaps this is partly the reason the cultures that have grown around these religions so often view the cat, the most magical of animals, with mistrust. Islam may be a legalistic religion, yet the faith delights in extravagant tales of the supernatural; consequently, Muslims have always been very fond of cats. In one legend, Muhammad once found his cat Meuzza sleeping on his robe. So as not to disturb his pet, the prophet cut off a sleeve and put on the rest of the garment. When he returned, Meuzza bowed to him in gratitude. Mohammed blessed the cat and her descendants with the ability to fall and land on their feet. When cats enter a mosque, it means good luck for the community. In one story from Oman, told by Inea Bushnaq, a cat caught a mouse and was about to devour it; the mouse begged to be allowed a prayer before death. When the cat agreed, the mouse suggested that the cat pray as well. The cat raised its arms in prayer, and the rat escaped. When a cat rubs its face, the story concluded, it is remembering the smell of the rat.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the German writer E. T. A. Hoffmann took on the formidable task of trying to imagine the feelings of a cat in The Life and Opinions of Kater Murr (1820). A passionate if somewhat reluctant romantic, Hoffmann felt cats were like those who work magic in verse or paint. Like artists, cats have mysterious insights. Like artists, cats often seem vain and impractical. Both cats and artists have an odd combination of innocence and guile. The tomcat Murr, who tells his story, affectionately mocks his master. He has adventures climbing the rooftops of the town. He reminds the reader in his preface, “Should anybody be bold enough to raise doubts concerning the worth of this extraordinary book, he should consider that he confronts a tomcat with spirit, understanding, and sharp claws.”

Poets always love mystery, and so they also love cats. W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot are among the many who have found inspiration in cats, but the most famous poem of all about cats is “My Cat Jeoffry” by Christopher Smart. The author takes precisely the characteristics that have impressed people as diabolic and uses them to make the cat a symbol of Christ:

For he keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin & glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life.

For Smart, the many paradoxes that surround the cat are proof of divinity.

In the decades immediately following World War II, people in the United States and Europe liked to romanticize alienation. In the slang of the Beatnik movement, a “cat” became somebody who preferred the colorful life of the streets to the mainstream of American society. In the last few decades of the twentieth century, cats temporarily replaced dogs as the most popular pet in the United States. Some reasons for this preference are pragmatic. Cats are smaller, eat less, need less space to exercise, demand less human attention, and are less expensive to care for than dogs. For those who find the emotional exuberance of dogs embarrassing, cats seem to offer emotional support without sacrifice of decorum. The relationship of cats to people can be warm and nurturing yet with a distance of respect; intimate yet full of riddles.

Nevertheless, cats kill billions of small birds and mammals every year in Europe and North America. The philosopher Jacques Derrida had an epiphany when his cat came upon him naked and he felt ashamed. This inspired an essay, The Animal that I therefore Am, in which he explained that, while his own existence might not be assured, his cat’s was beyond question. Perhaps Derrida’s shame was a refined sort of fear, and his experience reflected the ancestral memory of a time when cats were mighty predators and human beings were prey.

DOG

Ay, in the catalogue ye go for men;

As hounds, and greyhounds, mongrels, spaniels, curs,

Shoughs, water-rungs, and demi-wolves, are clept

All by the name of dogs. …

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Macbeth

Around 12,000 BCE in Eurasia—though according to some ethologists, much earlier—the dog became the first animal to be domesticated by human beings. Cats continue to appear wild even when raised in the family living room. Sheep and cattle generally stay together in herds, even under human direction. In the continual war between man and nature, only dogs appear to be unequivocally on our side. According to a legend of the Tehuelche Indians, after the sun god had created the first man and woman, the deity immediately created a dog to keep them company. Emotionally, dogs seem akin to human beings. Some people believe that dogs are the only animals apart from humans that can feel guilt. Others dismiss that perception as an anthropomorphic illusion or even as canine hypocrisy. People often regard dogs as icons of either the faithful companion or the sycophant. The dog joins the realms of culture and nature; in much the same way, the mythic dog serves as a mediator between life and death.

Already in ancient Egypt, dogs and cats were the most beloved of pets. According to Herodotus, when the family dog died, all members of the household would shave their whole bodies, including their heads, to show their mourning. Many Egyptian pictures have come down to us of people caressing dogs, as well as using them in the hunt. While cats were associated with both the sun god Ra and the goddess Bastet, dogs were associated with the underworld and with death. The appearance of the Dog Star, Sirius, was a sign that people should prepare for the rising of the Nile River. (The association of dogs with the star Sirius reaches all the way from Egypt to Mexico and China.) Plutarch, however, reported in his essay “Isis and Osiris” that when the blasphemous conqueror from Persia, Cambyses, had slain the sacred bull Apis, only dogs would eat the body, and so the dog lost its status as the most honored animal among Egyptians.

Tombs in which owners were interred with their dogs, either as canine effigies or in the flesh, have been found throughout the ancient world. They are not only common throughout Eurasia and parts of Africa but also in pre-Columbian America. Just as dogs led hunters tracking game through the wilderness, they were expected to guide people through the next world.

Their keen sense of smell gave dogs an ability to guide people in the hunt. A dog could find the location of game that was not even remotely visible. After the hunt, a dog guided people through the woods back to their settlement. We should remember that this was long before the use of the compass or of even remotely accurate maps. This ability must have impressed people as miraculous. Small wonder that a vast range of cultures on every continent have regarded dogs as guides to the world after death!

This ad from the early twentieth century exploits the dog’s reputation for fidelity.

(Courtesty of RCA)

Though dogs are occasionally seen as solar animals, they are usually associated, like cats, with the moon. Perhaps this is because they howl at the moon, as do their relatives—wolves, coyotes, and jackals. Many cultures understand the howling of dogs as an omen of death. According to Jewish tradition, they can see the angel of death. In Greek mythology, they are companions of the lunar goddesses Artemis and Hecate. In Virgil’s Aeneid, dogs howl at the approach of the darker and more magical lunar goddess Hecate, who herself is accompanied by dogs. Several traditions also make dogs the guardians of the underworld. The best known is Cerberus, who keeps watch at the entrance to Hades in Greco-Roman mythology. According to Hesiod, this dog had fifty heads, though later writers reduced the number to three.

In Norse mythology, the abode of the dead is watched over by the enormous dog Garm. When the final battle at the end of the world comes, Garm will swallow the moon. This monstrous dog will finally do battle with the Tyr, the god of battles, and both will be slain. In Hinduism and Buddhism, two dogs accompany Yama, the lord of the dead. They each have four eyes, and serve their master by searching out those who are about to die. In Aztec mythology, the departed soul descended to the underworld, and then came to a river guarded by a yellow dog. In European folklore, demonic dogs accompanied the Wild Huntsman across the sky in his search for lost souls. To even hear the hounds meant that you would die soon. In the lore of West England, the Devil’s Dandy Dogs passed over the moors during storms, breathing fire and tearing hapless strangers to pieces.

In the religion of the Aztecs, the canine diety Xolotl was also intimately associated with the world of the dead. According to an Aztec legend, human beings had once died out completely, and the gods wished to bring them back. Xolotl traveled beneath the ground to obtain the bones of the departed people. This intrusion angered the god of the dead, who pursued Xolotl, making him stumble, fall, and break the bones in many pieces. Xolotl recovered the bones and brought them back to surface of the Earth. When the gods sprinkled the bones with their own blood, the pieces became living men and women of many shapes and sizes.

A further reason for the association of dogs with death is that packs of feral dogs roamed the entire ancient world, searching for carrion, which included the bodies of human beings. Perhaps the greatest disgrace for an individual in almost cultures of the Mediterranean was to have his/her corpse eaten by dogs. In Homer’s The Illiad, the Trojans dreaded that this would be the fate of Hector’s body, after their champion was killed by Achilles. In Sophocles’ Antigone, the heroine feared that would happen to her brother, Polynices, if he were not given a proper burial. In Ovid’s Metamorphosis, the hunter Acteon experienced an especially demeaning death, changed by the goddess Diana into a stag and killed by his own hounds. Because Jezebel, wife of King Ahab of Israel, spread the worship of Baal, the prophet Elijah prophesied that dogs would devour her body. Jehu later ordered her thrown down from a window, and those who went to bury her found only the skull, feet, and hands.

Lady Wilde has written of dogs in Ireland: “The peasants believe that the domestic animals know all about us, especially the dog and the cat. They listen to everything that is said; they watch the expression of the face and can even read the thoughts. The Irish say it is not safe to ask a question of a dog, for he may answer, and should he do so the questioner will surely die.” The dog certainly shares the life of human society more intimately than any other animal. This, of itself, can make people feel uneasy. Human beings view dogs with a strange combination of affection and contempt, of domination and fear.

The name of Cuchulainn, the popular hero of Celtic myth, literally means, “hound of Culann.” When he killed a smith’s ferocious hound, Cuchulainn had to take on himself the role of the creature he had killed. When roused to battle, his appearance changed. His eyes bulged or contracted. His jaw opened from ear to ear, like that of a dog, while a light like the moon rose in his head. When three witches in the form of crows tricked him into eating the flesh of a dog, as well as violating other taboos, Cuchulainn was soon killed.

Dogs were held in special reverence in Persia. According to legend, Cyrus, who founded the Persian Empire, was left out to die at birth, but then saved by a bitch that suckled him. In the religion of Zoroaster, which began in Persia, a dog had to accompany a funeral procession to ensure that the deceased had a peaceful journey to the next world. The Zoroastrians believed that dogs were able to see spirits, and so they could protect families from evil powers beyond the awareness of human beings. In gratitude for this defense, families were expected to feed hungry dogs, using ritualistically prepared food. The members of the family then said prayers as the dog ate. Dogs guarded the Cinvat Bridge that led to the next world, protecting the righteous but leaving the unrighteous to demons. In the religion of Mithras, the major rival to Christianity in the latter Roman Empire, a dog would be among the animals to accompany Mithras during the sacrifice of a great bull to rejuvenate the world. After the sacrifice, the dog would lap up the blood that had been spilled.

Just as the dog guards the home, people in the ancient world also thought of dogs as guarding the body from demons or disease. In Mesopotamia, the dog was sacred to Gula, the Babylonian goddess of healing. At times, she was represented as a bitch suckling her pups. In her human form, dogs accompanied her. Many dog figurines have been found in her temple, and they were used to ward off illness. In Greece, a dog generally accompanied Asclepius, the legendary doctor who once raised a man from the dead.

Dogs were, for the most part, favorably regarded in the Greco-Roman world. Many people find the most touching scene in Homer’s The Odyssey occurred when the hero finally returned home and was recognized only by his hound, Argos. The dog wagged his tail and then died. The Greeks and Romans sometimes wrote very affectionate epitaphs for their dogs.

The philosopher Diogenes, a contemporary of Alexander the Great, called himself a “hound.” Members of his school were known as “cynics,” after the Greek word for “doglike.” Like dogs, they lived in the society yet did not fully belong to it. Since then, dogs have often symbolized alienation. Diogenes not only praised the fidelity and the modest needs of dogs but also their lack of shame, since they would not hesitate to urinate or copulate in public.

Ancient authors such as Ctesias and Pliny the Elder wrote of the cynocephali, who had human bodies and the heads of dogs. These figures ultimately go back to the jackal-headed Egyptian deity Anubis. After Alexander had conquered Egypt, his soldiers conflated Anubis with their God Hermes, since both were guides for the dead. The soldiers called this composite deity Hermanubis, and erected a temple to him in Alexandria, which became one of the most popular shrines in the ancient world. In time, his cult was finally absorbed into Christianity, and Hermanubis became Saint Christopher, who is often portrayed with the head of a dog.

In the Middle Ages, Saint Roche, who is invoked against diseases, was depicted with a dog. This holy man worked with victims of the bubonic plague. One day, however, he himself was with stricken and sores appeared on his body. Saint Roche wandered into the woods to die, when a dog came up and licked the infection. With the help of the dog, which also brought him bread, Saint Roche miraculously recovered.

In Medieval burials, there is a remnant of the tradition in which the dog serves as a guardian to the next world. The lord and lady of the house would often be buried with their dogs. Splendid sculptures and brass reliefs on graves show the deceased stretched out with a faithful dog at his or her feet. Today, dogs are often buried in pet cemeteries, seldom with their masters, yet many people still hope to be reunited with a beloved pet in the world beyond.

Throughout the Middle Ages, travelers spread accounts of dog-men in distant lands, especially the mythical kingdom of Prester John in India. One popular legend is that Saint Christopher was from a race of savage cynocephali, who ate human flesh. They could not speak but only bark. However, in answer to his wordless prayers, God granted Christopher human speech. Another tale accounts for his strange appearance by telling that Saint Christopher was once extraordinarily handsome, but prayed to God for the head of a dog, so that women would leave him in peace.

A version of this deity also entered Chinese legend. One very popular tale tells how a dog married a princess. Barbarians had invaded from the west, and the desperate Emperor promised that anybody who could drive back the enemy might marry his daughter. A dog heard the pledge, crept behind enemy lines and killed the opposing commander; he chewed off his victim’s head, brought it back, and presented it to the Emperor. When they discovered what had happened, the barbarians withdrew. The dog, which could speak like a human being, then reminded the Emperor of his promise. When the Emperor objected that marriage between a person and an animal was impossible, the dog replied that he could be made human by being placed under a bell for 280 days, provided that nobody disturbed him in the interim. This was done, but when only one day remained the Emperor was overcome with curiosity and lifted the bell, to see a creature with a human body and a canine head. The marriage went ahead as planned, and the tribe known as the Fong of Fuzhou claim to be descended from the couple.

Closeness to humanity has by no means necessarily worked to the advantage of dogs. We often try to judge dogs by human standards, which may not always be appropriate. We include them in human hierarchies, where they are at or near the bottom of the scale. The epithet “dog” traditionally suggests a combination of contempt and mistrust, such as masters would feel for their slaves. We use the term “ass-kisser,” taken from the greeting behavior of dogs, to describe hypocritically servile people. “Bitch” is used as a derogatory term for an overbearing woman or an effeminate male.

Partly in reaction to other cultures, especially that of Egypt, the Hebrews felt a repugnance for the dog. Not only is the dog an “unclean” animal in the Old Testament, but a revulsion against the dog is expressed repeatedly in very graphic terms: “As a dog returns to its vomit, so a fool reverts to his folly” (Proverbs 26:11). The view in the New Testament is not much more generous. Revelations lists “dogs” (which might be a metaphor) among those who must remain outside the kingdom of Heaven, together with “fortunetellers,” “fornicators,” “murderers,” “idolaters,” and “everyone of false speech and false life” (22:15).

Dogs are often compared to the enemies of Israel in the Old Testament:

Yahweh, God of Sabaoth, God of Israel,

Up, now, and punish these pagans, show no mercy to these villains and traitors!

Back they come at nightfall,

Snarling like curs,

Prowling through the town (Psalms 59:5-6).

The Hebrews, who were very fastidious about the preparation of food, insisted that animals be slaughtered according to prescribed rituals. In addition to taking a very dim view of the hunt in general, the people of Israel regarded meat touched by hunting dogs as unclean.

Islam also takes a negative view of dogs, though there are noteworthy exceptions. Muslem tradition places nine animals in heaven, including two dogs. One is the dog of the apocryphal prophet Tobit. The other is Kasmir, the dog of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, from a Christian legend that passed over into Islam. Seven young Christians took refuge in a cave to escape persecution by the Roman soldiers during the reign of the Emperor Decius. They slept for two hundred years. After waking, one of them went into town to purchase provisions. He was amazed to find that almost everyone had converted to Christianity. According to the Koran, Kasmir kept watch outside the cave for the entire time, neither eating, drinking, nor sleeping.

Even in Europe, it took some time for dogs to be fully accepted as pets, especially among the middle and lower classes. In 1613, Margaret Barclay of Scotland was tried for witchcraft. With the assistance of another woman, Isobel Insh, and in the company of a black lap dog, she had allegedly made a clay image of mariners and their boat one night. Then, together with the dog, she had gone down to the shore and cast these images into the waves. Immediately, the water had turned red and the sea had begun to rage. At about the same time, a ship had gone down near the coast, killing all the crew except two men. The daughter of Isabel Insh, a girl of only eight, was called in to testify, and claimed to have witnessed the witchcraft, adding that her mother been present only at the making of the clay images but not when the spell was cast. The child added that the dog gave off fire from his jaws and mouth to illuminate the scene. Margaret Barclay was forced to confess under torture. Though she later retracted the confession, she was executed.

But absolute fidelity to one’s lord and master, exemplified in faithful dogs, was an especially central virtue of the ancient and feudal worlds. There are countless stories throughout the world of dogs that kill themselves after their masters have died, often by refusing all food. Pliny the Elder wrote of a dog named Hyrcanus that threw itself on the blazing funeral pyre of his master. The most famous of all is Hachiko, an akita dog that would go to meet his owner, Professor Ueno, every day after work at the Shibuya train station near Tokyo for about a year. One spring day in 1925, the professor did not return, for he had unexpectedly died. Until its own death almost ten years later, Hachiko continued to return to the station to wait. There is now a monument to Hachiko in the Shibuya train station, and this dog is upheld as a model of family loyalty to Japanese children.

Seldom do people pass the test of canine loyalty. One of the few who did is Yudhishthira, in Hindu myth, when he ascended to heaven without his dog. There was thunder then a great light. He could see the god Indira waiting for him in the divine chariot. Invited to enter, Yudhisthira stepped aside so the dog might go first. Indira objected, saying that the presence of a dog would defile heaven. Yudhisthira replied that he could conceive no greater crime than to send the faithful dog away. At that moment, the dog was transformed into Dharma, the god of righteousness. The words of Indira had been a final test, and Yudhisthira had shown his worthiness through fidelity to his companion.

Just as many tales celebrate the fidelity of dogs, others lament the inability of human beings to reciprocate this loyalty. A good example is the tale of Guinefort, a greyhound on the estate of Villars near Lyons in France. A knight had left his baby to be guarded by Guinefort, and then later returned to find the nursery a bloody mess. The baby was missing, and Guinefort greeted the man with bloody jaws. The outraged father killed Guinefort, but then soon heard the child crying. On finding the mangled body of a snake, he realized that Guinefort had actually saved the infant from an attacking viper. The grave of the dog became a site of pilgrimages, where parents would bring sickly or deformed children to be healed. Monks in a nearby monastery looked on in consternation while peasant women prayed to the dog, hung swaddling clothes in nearby bushes, and practiced what seemed to be pagan rituals.

The treatment of dogs not only reflects, but often exaggerates, the social norms of their society. In aristocratic societies, human beings were valued largely according to their ancestry. Like kings, queens, and nobles, the thoroughbred dogs in noble houses had recorded bloodlines that went back several generations and fabricated ones that went back to remote antiquity, often to King Solomon or even Adam. A bit ironically, the pedigrees of dogs gained in importance with the rise of the middle class in the eighteenth through twentieth centuries, precisely as aristocratic ties of blood lost their significance.

With the rise of the middle class in Victorian times, the unconditional fidelity of dogs became a nostalgic reminder of the Middle Ages, a period that was widely idealized. Since one could no longer demand such loyalty of people, one valued the virtue all the more in hounds. One story that was constantly retold is that of the “Dog of Montargis,” which belonged to Aubry de Montdidier, a favorite courtier of the French King Charles V. The dog’s master was murdered in the wood of Montargis near Orleans in 1371. The dog was the only witness and followed the murderer, Robert Macaire, everywhere, constantly barking at him in an accusatory manner. Finally, a duel between the dog and man was arranged. After being badly defeated, Macaire confessed to his crime and was executed.

The Nazis wanted to promote unquestioning loyalty and obedience, a quality that found best exemplified in dogs. Hitler once said that he trusted nobody but his girlfriend, Eva, and his dog, Blondie. Then, when society had thoroughly industrialized, dogs served as nostalgic reminders of the rural past. Especially in the 1950s and early 1960s, such dogs such as Lassie and Rin Tin Tin were enormously popular on television.

Our taboo against cannibalism extends to dogs, but only to a limited extent. Until very recent times, dogs were eaten almost everywhere, regularly by the poor and by far more people when food became scarce. There were dog slaughter houses, and dog meat was available at some delicatessens and restaurants. Germans, for example, ate about 84 tons of dog meat or more every year in the decade leading to World War I; that figure increased by almost a third during the Great War, briefly declined, and then shot up even more during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The phrase “dog eat dog,” referring to ruthless, unrestrained competition, originated in the United States during the Great Depression, and probably originally referred to this practice.

The Dog Catcher remained a fixture of everyday life in Western countries at least until the second half of the twentieth century, and feral dogs that were captured might at times be not only killed but also eaten. Only since the end of the World War II, the consumption of dogs throughout Europe and North America has become miniscule, and the professions of Dog Butcher and Dog Catcher have almost disappeared (though we still have Animal Control Officers, with far broader responsibilities). In North Africa and East Asia, people continue to eat dogs, but Westerners usually find this utterly uncivilized, and governments usually try to discourage it.

Feral dogs have also become relatively rare in the West, though workers in animal shelters continue to agonize over whether, and when, dogs should be euthanized. Packs of such dogs remain common in much of the world, and, in villages throughout much of Africa, people who adopt a dog do so not by taking it into their homes but simply by feeding and befriending it.

In early space exploration, dogs were often used as surrogates for human beings. The first living creature to be sent into orbit was a Samoyed named Laika, sent up in a Soviet satellite in 1957. After six days, the oxygen ran out and she died, but her corpse continues in orbit to this day. The death evoked wide protests, and Laika has come to symbolize the fragility of all life in this age of scientific exploration. In the next few decades, however, computers, which had attained great sophistication, largely replaced dogs, other animals, and, to an extent, even people in outer space.

As the pragmatic usefulness of the dog in our daily lives is gradually reduced, the symbolic importance of dogs may even be increasing. In this age of electronic security systems, dogs are relatively inefficient at guarding the home. Nevertheless, most people have seen the cartoon dog McGruff, in a trench coat and floppy hat, who tells people on television to “take a bite out of crime.” Dogs are used to sell a vast variety of products related to security, from alarms to programs against computer viruses.

Today, dogs are almost completely integrated into the consumer culture of Europe and North America. Dogs now have special gyms, fashions, gourmet foods, beauty parlors, jewelry, five star hotels, television shows, therapists, and almost everything else that people have. But dogs, like us, pay for all of this luxury with freedom. In the last decades of the twentieth century, most urban communities have prohibited dogs from running free even in city parks.

Not everybody likes dogs, but those who do are very passionate about them. Dogs often appear helpless, yet they are usually able to take care of themselves pretty well. This combination of vulnerability and strength makes dogs, for good or ill, so very “human.”

ETS—ANIMALS KEPT IN THE HOME SOLELY TO OFFER COMPANIONSHIP to people—are largely a phenomenon of modern Western culture. Prior to that, animals were often kept in or near human dwellings, and intense bonds developed between them and people, though they almost always had either a religious or pragmatic purpose. In Rome, people would sometimes keep a snake in their home, believing it to be the spirit of an ancestor, a practice that survived into modern times in parts of Italy and Eastern Europe. Caged birds were also kept, largely to provide music. In the Middle Ages, aristocrats often kept dogs for hunting or to guard the home. Cats, as well as dogs, were used for catching mice. Hawks were used to catch rabbits and other small game. Paradoxically, as such purposes have been increasingly taken over by mechanical devices, the ownership of pets has soared. The Humane Society of the United States estimates that in 2011 39% of American households had at least one dog, while 33% had at least one cat. To some extent, these animals may serve as mediators with the natural world. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, dogs especially have been so completely integrated into human society that it is questionable how much they can still serve that purpose. They no longer have their own detached “doghouses,” but live in the home, where they are elaborately trained, fed prepared foods, and seldom allowed to run freely. Today, advertisements and popular articles often refer to people with companion animals not as “owners” but as “pet parents,” while the pets themselves are called “boys” and “girls.” In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, scholars have increasingly recognized the novelty of modern pet-keeping, and a vast academic literature has accumulated around the study of the relationships between pets and human beings. Scholars sometimes prefer the term “companion species,” coined by Donna Haraway, since it embraces not only contemporary pet-keeping, but also its many precedents in the co-evolution of animals and humans.

ETS—ANIMALS KEPT IN THE HOME SOLELY TO OFFER COMPANIONSHIP to people—are largely a phenomenon of modern Western culture. Prior to that, animals were often kept in or near human dwellings, and intense bonds developed between them and people, though they almost always had either a religious or pragmatic purpose. In Rome, people would sometimes keep a snake in their home, believing it to be the spirit of an ancestor, a practice that survived into modern times in parts of Italy and Eastern Europe. Caged birds were also kept, largely to provide music. In the Middle Ages, aristocrats often kept dogs for hunting or to guard the home. Cats, as well as dogs, were used for catching mice. Hawks were used to catch rabbits and other small game. Paradoxically, as such purposes have been increasingly taken over by mechanical devices, the ownership of pets has soared. The Humane Society of the United States estimates that in 2011 39% of American households had at least one dog, while 33% had at least one cat. To some extent, these animals may serve as mediators with the natural world. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, dogs especially have been so completely integrated into human society that it is questionable how much they can still serve that purpose. They no longer have their own detached “doghouses,” but live in the home, where they are elaborately trained, fed prepared foods, and seldom allowed to run freely. Today, advertisements and popular articles often refer to people with companion animals not as “owners” but as “pet parents,” while the pets themselves are called “boys” and “girls.” In the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, scholars have increasingly recognized the novelty of modern pet-keeping, and a vast academic literature has accumulated around the study of the relationships between pets and human beings. Scholars sometimes prefer the term “companion species,” coined by Donna Haraway, since it embraces not only contemporary pet-keeping, but also its many precedents in the co-evolution of animals and humans.