HE CAVE PAINTINGS OF PALEOLITHIC EUROPE, TOGETHER WITH artifacts and possible parallels with other cultures based on hunting, suggest a solidarity with animals that continues to intrigue people today. The mentality that produced them is, however, impossible to reconstruct them with any confidence. We do not know, for example, whether the people thought of the shedding of blood as a transgression, which needed to be assuaged through ritual. We do not know whether hunting was accompanied by feelings similar to what we now call “guilt.” However that may be, some scholars of myth have attempted to trace not only the origins of religion but even storytelling itself to the hunt. Many contemporary sportsmen continue to use elaborate rituals, but are often frustrated at the difficulty of communicating the meaning of the hunt to outsiders. Their identification with the hunted animal, though it may seem paradoxical, can be very intense. In some cases, such as that of the Great Plains Indians, this totemic bond can be the foundation of a culture.

HE CAVE PAINTINGS OF PALEOLITHIC EUROPE, TOGETHER WITH artifacts and possible parallels with other cultures based on hunting, suggest a solidarity with animals that continues to intrigue people today. The mentality that produced them is, however, impossible to reconstruct them with any confidence. We do not know, for example, whether the people thought of the shedding of blood as a transgression, which needed to be assuaged through ritual. We do not know whether hunting was accompanied by feelings similar to what we now call “guilt.” However that may be, some scholars of myth have attempted to trace not only the origins of religion but even storytelling itself to the hunt. Many contemporary sportsmen continue to use elaborate rituals, but are often frustrated at the difficulty of communicating the meaning of the hunt to outsiders. Their identification with the hunted animal, though it may seem paradoxical, can be very intense. In some cases, such as that of the Great Plains Indians, this totemic bond can be the foundation of a culture.

HART AND HIND

O world! Thou wast the forest to this hart;

And this, indeed, O world! The heart of thee.

How like a deer, stricken by many princes,

Dost thou here lie!

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Anthony and Cleopatra

Just as we think of the male lion in terms of his luxurious mane, we think of the stag in terms of his enormous antlers. These also define the female, the deer (or hind), through their absence or, in some species, their relatively small size. Together hart and hind represent nothing less than the primordial division into male and female. Through this symbolism, they are also intimately associated with the forests where they live. They move among the trees silently, blend in perfectly, and have a way of suddenly appearing, which makes them seem to be the very soul of the woods.

Most of the time, we use the word “deer” as a plural to include both male and female, suggesting that the species is at least primarily feminine. The English word “deer” originally meant “animal” in general, as opposed to humankind, just as its relatives such as “tier” (German) and “dier” (Dutch) still do. The current meaning of the word in English was only established in the 15th century. This etymology suggests that people thought of deer as a sort of epitome of what it means to be a beast of the forest and field—our quintessential Other.

Why was the deer not domesticated in Neolithic times, along with the sheep, goat, pig, and chicken? It had already long been a major source of food for human beings, and is fairly easily tamed. The answer of anthropologist Betrand Hell is that leaving the deer free to roam the forests was a deliberate, if not necessarily conscious, part of the social construction of the domestic and wild realms. The deer would embody the forest as a realm of wonder, danger, magic, and adventure. Human beings needed the hunt, and its mystical solidarity with the animal world, more than they craved an easy source of protein.

One of the earliest possible mythological creatures is a muscular, bearded human figure known as “the sorcerer,” bearing antlers of a stag, painted over a millennium before Christ in the French cave of Trois Fréres. His head is disproportionately large, and the lines of his body are sharply angular. Perhaps he is doing a sort of dance. This figure could be either a nature spirit or else a shaman who wears the antlers and mask of a stag. For those who created the image, the two alternatives were perhaps not so very far apart, since the spirit of a stag could have possessed a shamanic dancer.

No creature is more quintessentially masculine than the stag, with his large shoulders, impressive size, athletic stride, and frequent propensity to fight. The doe seems comparably feminine with relatively modest size and cautious, delicate steps. Furthermore, does tend to remain in a herd, suggesting the traditionally feminine role of women as guardians of the home. Stags, by contrast, tend to be solitary except during mating season. One may choose to call the contrast either “archetypal” or “stereotyped,” but it is hard not to think of the division of roles along lines of gender in many human societies.

This solitary life is why the stag has been associated with many holy anchorites. Saint Hubert, for example, was once a pleasant but shallow courtier at the court of King Pepin in France. His great passion was for the chase, and he even skipped church service on Good Friday to hunt. When he finally caught sight of the stag, he saw a vision of the crucifix between its antlers, and the voice of Christ warned Hubert that he must either accept God or end up in Hell. Hubert repented his frivolous ways, became a hermit, and devoted himself to God. He is now the patron of hunters, and a festival in his honor is still celebrated by them every year in the forests of France.

Christ also took the form of a stag in visions of Saint Pacidus and Saint Eustace, about whom very similar tales are told. The anchorite Saint Giles once sheltered a deer from a hunting party of the Emperor Charlemagne, and an arrow intended for the stag hit the saint instead. In gratitude, the deer brought him milk every day, while the King built a monastery in his honor. Saint Ciaran, and early disciple of Saint Patrick, had several deer among his earliest disciples when he became a missionary in Ireland. A stag accompanied Saint Canice, an Irish hermit, and offered the holy man his antlers as a bookstand.

The stag has not only been a common symbol of Christ, the resurrected God, but it also represented the entire natural world, subject to cycles of germination, growth, death, decay and resurrection. Deer, like plants but unlike most animals, clearly reflect the seasons in their appearance. Their fur acquires a richer color in summer. Even more significantly, the males of many species shed their horns every year. Up through Elizabethan times, it was widely believed that the sex organs of stags as well were shed and rejuvenated every summer. The lifespans of large trees were often attributed to stags. One popular Medieval legend concerned a stag that was given a golden collar by Alexander the Great (Caesar, Charlemagne, or King Alfred in other versions). This animal was reportedly found hundreds of years later, still fully vigorous.

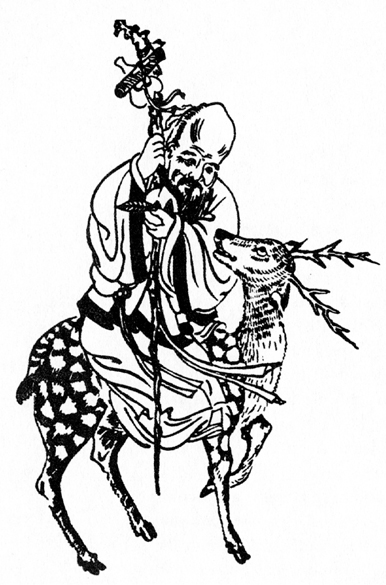

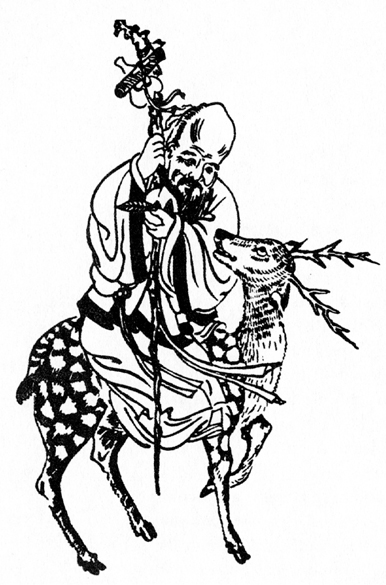

Shou Hsing, a Chinese god of longevity, mounted on a stag.

Tradition grants even greater longevity to deer in Asia. According to Chinese tradition, deer can live over 2,500 years if never killed. During the first 2,000 years, the skin of the deer gradually turns white; its horns turn black in the next 500. From that time on, the deer ceases to grow or change, though it may subsist on only clear streams and lichens in the mountains.

The identification of the stag with the forest was so intimate that it guided scientific opinion until around the end of the eighteenth century. The horns of the stag were, throughout the Middle Ages, understood as the branches of a tree, the skin covering them as a kind of bark. Georges Luis LeClerc de Buffon, a foremost zoologist of the eighteenth century, theorized that, since the stag nibbles so much on trees, branches eventually grew out of its head.

The association with the forest is partly responsible for another important feature of the stag in folklore. While the earth is traditionally perceived as feminine, we generally view trees, with a few exceptions, as masculine. The ash was sacred to Odin, the oak to Zeus and Thor. Deer have frequently been depicted around the base of a tree of life in ancient Mesopotamia and several other regions. According to Norse mythology, stags nibbled at the base of the world tree Yggdrasil.

The horns of the stag have been worn by many highly masculine heroes and gods in folklore and mythology, such as the Celtic god Cernunnos. Stags sometimes drew the chariot of Dionysius, the Roman Bacchus. Neo-pagans of today celebrate the stag as a symbol of male energy, and, by extension, the god. In European folklore, the sexuality associated with this animal is fierce and unrestrained, yet also completely chaste. Neither fundamentally romantic nor promiscuous, it is close to the undifferentiated sexuality of the vegetable realm than that of either other animals or human beings.

By about the time of Charlemagne, the hunt of the stag was a “sport,” a privilege of princes and aristocrats that was forbidden to the peasantry, often on pain of death or mutilation. It was set apart from the everyday world by elaborate costumes, vocabularies, and rituals. A solemn rite, reminiscent of Holy Communion, followed the slaying of the stag. The body of the stag was divided among participants, from the dogs to the horsemen, and the head was finally presented to the lord of the manor.

A doe traditionally accompanies Artemis, goddess of the hunt and protector of animals. King Agamemnon, commander of the Greeks in their assault on Troy, once killed a hind sacred to Artemis, boasting that he was greater than she in the hunt. The goddess stopped the winds, thus forcing the Greek ships to remain in port. An oracle told the Greeks that there would only be wind when Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia to Artemis. Under pressure from the other Greek princes, Agamemnon finally complied. When Iphigenia was led to the altar, Artemis substituted a hind and carried away the young girl in a cloud to Tauris on the island of Crimea, where she became a priestess.

In his Metamorphoses, Ovid tells how the young hunter Acteon once came upon the goddess Diana, bathing with her nymphs at a stream. He was so overwhelmed by the sight that he stood transfixed, until the goddess became aware of him and shouted, “Tell people you have seen me, Diana, naked! Tell them if you can!,” as she splashed water in his face. Acteon looked into the water and saw, with horror, that he was turning into a stag, and then he was torn apart by his own hounds. Some interpreters believe that Diana here represents Julia, daughter of the Emperor Augustus, while Acteon represents Ovid himself, who was banished for witnessing one of her affairs. The unfortunate hunter may also be a man who intrudes on women’s mysteries. For alchemists of the Renaissance, Acteon was the adept who, on understanding the nature of reality, must die in order to be reborn.

The deer was also sacred to many other archaic goddesses including the Mesopotamian Ninhursag, the Egyptian Isis, and the Greek Aphrodite. The nurturing quality of a hind is shown in the Greek myth of Telephus, son of Hercules and Auge. His mother, to conceal her affair, hid the infant Telephus in the temple of the goddess Athena, which caused the local harvests to fail. When this was discovered, the infant was exposed on a mountain to die, but he was saved by a hind that suckled him.

The Old Testament often celebrates the hind as a symbol of feminine virtue, for example:

Find joy with the wife you married in your youth,

Fair as a hind, graceful as a fawn.

Let hers be the company you keep,

Hers the love that ever holds you captive (Proverbs 5:19).

Psalm 42 begins “As the doe longs for running streams, so longs my soul for you, my God.”

Stag and hind share an importance as divine messengers throughout most of Europe. In countless epics and fairy tales, deer appear to the hero and guide him or her through the woods. The search for the Holy Grail begins as knights of King Arthur follow a white stag into the woods. According to legend, Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, was once so intent on pursuit of a stag that he became separated from his hunting party, fell from his horse while crossing a stream, and became lost in a vast forest. As his men found him next morning, daylight revealed a bush or roses blossoming in the snow, a miraculous sign that he should build a cathedral in that place.

The stag that took pride in his horns found they got caught in the trees and prevented his escape from the hunters, in the Aesopian fable.

(Illustrated by J J. Grandville, from Fables de la Fontaine, 1839)

In Celtic myth, deer are guides to the Other World, while in the lore of Ireland they are also sometimes the cattle of fairies. The deer hunt also provided a frequent metaphor in Medieval and Renaissance culture for courtship. Imagery taken from the chase was used to express the fear, longing, concealment, and tension that are often part of erotic intrigues. In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, Curio tried to divert the melancholy Duke Orsinio:

CURIO: Will you go hunt, my lord?

DUKE: What, Curio?

CURIO: The hart.

DUKE: Why, so I do, the noblest that I have.

O, when mine eyes did see Olivia first,

Methought she purg’d the air of pestilence!

That instant was I turn’d into a hart,

And my desires, like fell and cruel hounds,

E’re since pursue me.

Even more frequently, the woman was viewed as the hunted deer. The horns of a stag were often used as a symbol of cuckoldry, an obsession in literature of the Elizabethan Age.

But for the more humble social orders, the deer were often bitterly resented as a symbol of oppression. In the stories of Robin Hood, the merry men living in Sherwood Forest constantly defied the Sheriff of Nottingham by feasting on the “king’s deer.” When the prohibitions against hunting deer by the peasantry were finally lifted, many commoners asserted their new freedom by pursuing the chase with enormous vehemence and cruelty. The British pastor Gilbert White complained “Unless he was a hunter, as they affected to call themselves, no young person was allowed to be possessed of manhood or gallantry.”

In Bambi, A Life in the Woods (1928), Felix Salten protested this indiscriminate hunting in his beloved Vienna Woods. The novel recounts the coming of a young stag named Bambi from his birth in a clearing. He learns the ways of the woods, fights off his rivals and mates with a hind named Filene. The tale ends with the death of Bambi’s father, at which point Bambi goes off by himself to become a guardian of the forest. The poacher is a figure of awe and terror who killed Bambi’s mother and allowed the deer no rest. Salten, himself an avid sportsman, later tried to draw a sharper distinction between the poacher and the legitimate hunter in a sequel. The enormously popular movie by Disney Studios that was based on the book (1942), however, further anthropomorphized Bambi and Filene, while it made “man,” known only through fires and bullets, seem like a brutal, sinister force of nature.

The close association of deer with the landscape is also found in the cultures of Native Americans. Several tribes of Mexico and the American Southwest including the Aztecs, Zuni and Hopi traditionally perform a deer dance to influence the elements and bring bountiful crops. The Yaqui Indians today generally follow a Catholicism that has blended with their traditional, tribal religion, and they have incorporated the deer dance into an Easter ritual that is performed every year. In all of these ceremonies, the chief dancer will wear either the head of a deer or antlers and will imitate the motions of the animal, which looks cautiously about while moving through the woods.

With the increasing suburbanization of North America and Europe, many deer have lost their fear of human beings. White tailed deer of North America, which live on browse at the forest’s edge, are now actually far more common than they were in the time of Columbus. Many suburbanites consider deer “pests” or “overgrown rats,” complaining that they cause traffic accidents or nibble at gardens. Perhaps even more seriously, they can prevent the regeneration of forests by eating young shoots. Perhaps it is only in the far North, where many of the few remaining wildernesses may still be found, that the ancient symbolism of the deer, particularly the moose, as guardians of the wood retains much of its vividness.

AMERICAN BUFFALO

“What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in the wintertime.”

—CROWFOOT

In Animals of the Soul, Joseph Eppes Brown writes that for the Oglala Sioux, “the buffalo (or “bison”) is the chief of all animals and represents the earth principle, which gives rise to all living forms.” Black Elk, the shaman who initiated him into the ways the Sioux, said that that hunting was a “quest for ultimate truth.” In the culture of the Indians of the Great Plains, the buffalo has a significance that seems, in many ways, to parallel that of the deer among Europeans. Both animals were hunted amid elaborate ritual and ceremony, and were often associated with visions. The buffalo embodies the prairie for the Indians, just as the deer embodies the forest for Europeans. Despite giving an impression of wildness, the forests of Medieval Europe were mostly preserves that were carefully managed around the needs of the deer, which would be hunted by royalty and nobility. In a similar way, Indians had managed the prairies around the buffalo by deliberately starting fires, destroying young trees and rejuvenating the grasses.

But these similarities resulted less in sympathy than in misunderstanding. For Europeans of the early modern period, hunting deer had long been an exclusive privilege of inherited wealth and power, and others who engaged in it were subject to terrible punishments. They could little comprehend that for the Indians, the hunt was a livelihood as well as a religious act. For the democratically minded emigrants to the New York, the Indian hunters seemed to be indulging in a life of idleness, much like the monarchs and nobles they had come to despise.

When this was painted, such hunts had long since disappeared, but were remembered with nostalgia by both settlers and Indians.

(Buffalo Hunt by William R. Leigh, 1947)

In pre-Columbian times, hunting buffalo on the Great Plains was a perilous enterprise. Occasionally, Indians were able to frighten a herd into stampeding off a cliff. More often, they would dress themselves in buffalo or wolf hides, at times mimicking the sounds and movements of those animals, as they waited for an auspicious time to strike. With horses imported by Europeans, hunting became much safer and more efficient, but that did not diminish the religious significance of the hunt. Perhaps the shared experience of galloping across the plains helped the Indians to identify more closely with the hunted buffalo. In the early twentieth century, Black Elk also told that his people had once been visited by a buffalo goddess in the form of a beautiful lady, the White Buffalo Calf Woman, who gave them a sacred pipe carved with the image of a buffalo calf, which is the center of their rituals. The Sioux, as well as the Pawnee, believe that a cosmic buffalo stands at the gate through which animals pass as they die and are reborn.

When the great westward migration of European Americans greatly accelerated at the end of the Civil War, pioneers passed through, and often tried to claim, what had been Indian territories. The United States military was unable to decisively defeat the Indians militarily until they began to deliberately destroy the buffalo herds, thus simultaneously attacking the Indians’ source of food and their religious beliefs. In 1850, there had been an estimated fifty million buffalo on the prairies; by 1900 only twenty-three were left in the United States and about 500 in Canada, and the Indians had been forced to surrender most of their lands. The prairies themselves had been transformed, often into pastures for European cows. Many Indians believe that the buffalo had sacrificed themselves and died in place of the Indians.

In the twentieth century, attempts have been made to preserve the buffalo in the United States. The largest herd is that in Yellowstone National Park, which contains a few thousand animals, and a few of them are now being transferred to tribal reservations. Many Indians still regard them as ancestors. For most Americans, Indian or not, the buffalo remain a symbol of the expansiveness and freedom of the open plains, in a mythic time before the innocence of the nation was lost. From 1920 through 1938, the treasury of the United States issued the Buffalo Nickel, with a buffalo on one side and the profile of an Indian, accompanied by the date and the word “liberty,” on the other. In 1994, a white buffalo calf named “Miracle” was born in Janesville, Wisconsin, and many Sioux elders interpreted the birth as the return of the White Buffalo Calf Woman, heralding the start of a new era.

HE CAVE PAINTINGS OF PALEOLITHIC EUROPE, TOGETHER WITH artifacts and possible parallels with other cultures based on hunting, suggest a solidarity with animals that continues to intrigue people today. The mentality that produced them is, however, impossible to reconstruct them with any confidence. We do not know, for example, whether the people thought of the shedding of blood as a transgression, which needed to be assuaged through ritual. We do not know whether hunting was accompanied by feelings similar to what we now call “guilt.” However that may be, some scholars of myth have attempted to trace not only the origins of religion but even storytelling itself to the hunt. Many contemporary sportsmen continue to use elaborate rituals, but are often frustrated at the difficulty of communicating the meaning of the hunt to outsiders. Their identification with the hunted animal, though it may seem paradoxical, can be very intense. In some cases, such as that of the Great Plains Indians, this totemic bond can be the foundation of a culture.

HE CAVE PAINTINGS OF PALEOLITHIC EUROPE, TOGETHER WITH artifacts and possible parallels with other cultures based on hunting, suggest a solidarity with animals that continues to intrigue people today. The mentality that produced them is, however, impossible to reconstruct them with any confidence. We do not know, for example, whether the people thought of the shedding of blood as a transgression, which needed to be assuaged through ritual. We do not know whether hunting was accompanied by feelings similar to what we now call “guilt.” However that may be, some scholars of myth have attempted to trace not only the origins of religion but even storytelling itself to the hunt. Many contemporary sportsmen continue to use elaborate rituals, but are often frustrated at the difficulty of communicating the meaning of the hunt to outsiders. Their identification with the hunted animal, though it may seem paradoxical, can be very intense. In some cases, such as that of the Great Plains Indians, this totemic bond can be the foundation of a culture.