HE FIRST FEW INCHES OF FOREST SOIL ARE WHERE BOTH THE DECAY OF organic matter and the regeneration of new life are most pronounced, and it is often hard to tell life from death. It is also a dwelling place of nature deities, such as Spider Woman in the mythology of the Navaho and Hopi Indians. In many highly formalized religions, especially the Abrahamic ones, the realm beneath the ground is Hell, where demons torment, cook, devour, and excrete sinners. For the fifteenth century CE alchemist Paracelsus, often considered “the father of modern medicine,” creatures of the earth (also called “earth elementals”) were “gnomes.” Our ground is their air, and they can see and walk through it. They are very small yet basically human in form, but, like people, they can have deformed births, which might take all manner of strange shapes. Fanciful as this may be, it does in ways describe life in the topsoil, where beetles and centipedes bore through the ground as easily as we walk over it.

HE FIRST FEW INCHES OF FOREST SOIL ARE WHERE BOTH THE DECAY OF organic matter and the regeneration of new life are most pronounced, and it is often hard to tell life from death. It is also a dwelling place of nature deities, such as Spider Woman in the mythology of the Navaho and Hopi Indians. In many highly formalized religions, especially the Abrahamic ones, the realm beneath the ground is Hell, where demons torment, cook, devour, and excrete sinners. For the fifteenth century CE alchemist Paracelsus, often considered “the father of modern medicine,” creatures of the earth (also called “earth elementals”) were “gnomes.” Our ground is their air, and they can see and walk through it. They are very small yet basically human in form, but, like people, they can have deformed births, which might take all manner of strange shapes. Fanciful as this may be, it does in ways describe life in the topsoil, where beetles and centipedes bore through the ground as easily as we walk over it.

ANT

In the ant’s house, the dew is a flood.

—PERSIAN PROVERB

A plague had destroyed the people of King Aeacus, and he begged Zeus to give him citizens numerous as the ants in a sacred tree. Zeus changed the ants into warriors. These were the Myrmidons, who later fought under Achilles. Ants resemble warriors in many ways: they march in columns; they show unbounded courage. No matter how large the adversary, they still attack. No matter how many are killed, they do not surrender or retreat. An ant that is decapitated will continue to bite at its adversary. For their size, ants are also the strongest creatures in the world, able to carry objects many times larger than they are.

Soldier ants on sentry duty.

(Illustration by Ludwig Becker)

According to another myth, Zeus changed himself into an ant in order to make love to the maiden Eurymedusa in Thessaly. She gave birth to a child named Myrmidon, ancestor of the martial race. Myrmidons were not only efficient warriors, but they also prospered in peace. Like ants, they would diligently work the soil.

The ants have regular access to the mysterious depths of the earth, where metals and jewels are found. Herodotus told of ants in India that were larger than foxes. These ants threw up huge heaps of sand that contained gold as they burrowed in the ground. The Indians watched from a distance, then quickly heaped the sand into bags and rode away on camels. They had to rely on surprise in these raids, since the ants were extremely swift in pursuit.

Ants holding an assembly in a pear tree.

(Illustration by Ludwig Becker)

In the fable of the industrious ant and the feckless grasshopper, attributed to the half-legendary Aesop (see Grasshopper), the ants appear almost as ruthless in their diligence as in their wars. “Idler, go to the ant; ponder her ways and grow wise,” said the Bible, in a passage traditionally attributed to Solomon (Proverbs 6:6). Around the world, the ant has long been proverbial for industry.

Creatures that live beneath the earth, near the world of the dead, are always frightening and mysterious. At festivals of the dead, Jains and certain Hindus feed the ants. West African tribes have traditionally believed that ants carry messages from the gods. In ancient Greece and Rome, ants sometimes appeared in prophetic dreams. When King Midas was a child, ants carried grains of corn to his lips as he slept, a sign that he would one day achieve enormous wealth.

According to Plutarch, when the Greek commander Cimon sacrificed a goat to the god Dionysus during a war with the Persians, ants swarmed around the animal’s blood. They carried blood to Cimon and wiped it on his big toe, predicting his immanent death. Ants are still used in divination. To step on ants brings rain. A nest of ants near your door means you will grow rich.

La Fontaine’s version of “The Grasshopper and the Ant.”

(Illustration by J. J. Grndville, from Fables de la Fontaine, 1839)

For all their reputation for ruthlessness, ants in folklore often protect the weak and vulnerable In the story “Cupid and Psyche” by the first-century CE Roman author Lucius Apuleius (in his novel The Golden Ass), the young girl Psyche had fallen in love with Cupid. The goddess Venus, mother of Cupid, did not approve of their union. She captured Psyche, locked the maiden up with a huge heap of mixed grains, and then demanded that all be sorted by nightfall. The ants pitied Psyche and carried the different grains, one by one, to separate piles.

According to Cornish legend, ants were fairies, which had, over the centuries, grown ever smaller and are now about to disappear. Other legends made them the souls of unbaptized children, who were admitted neither to Heaven nor to Hell. All such tales reveal a kinship that people feel with ants. Part of the reason may be a similarity of their bodies to ours, with large heads and hips but slender waists. It may also be that their small size and consequent vulnerability elicits our sympathy.

Ants appear in many European tales as grateful animals. In one fable by La Fontaine, a dove uses a blade of grass to a rescue a drowning ant. Later, a hunter tries to shoot the dove. The ant bites the man on the heel and makes his arrow go astray.

In Aztec mythology, red ants once kept the seed of maize hidden in a mountain. The god Quetzalcoatl transformed himself into a black ant and stole the seed in order to bring food to humankind. As in so many European stories, grain formed a bond between ants and humanity. The Hopi Indians traditionally believe that the first human beings were ants.

In Walden, Thoreau reported going to a woodpile to find a battle between two varieties of ants, with the ground already “strewn with the dead and dying.” In one camp were “red republicans, “in the other, “black imperialists.” “On every side they are engaged in deadly combat … and human soldiers never fought so resolutely,” Thoreau continued. A valiant Achilles among the red ants came to avenge some fallen comrade. He killed a black Hector, while the enemy cavalry swarmed over his limbs. The gentle hermit of Walden Pond wrote of this carnage with great excitement. Perhaps those who believe there are no more heroes today should spend more time around the anthills. The ants live in a world a bit like that of old romances, filled with monsters (that is, termites, spiders, woodpeckers, or human beings). Kingdoms with mysterious powers surround the anthill, and ants must constantly battle in order to survive.

Perhaps when kings and lords ruled most of the world, it was a bit easier to identify with ants. The anthill seemed to be the perfect authoritarian state, in which everyone unquestioningly accepted a role. As governments became more democratic, it was a bit harder to believe that such a society was either possible or desirable. Artists and writers tried to individualize ants, and that certainly has not been easy.

When people look closely at ants, there is no telling what they may find. Michel de Montaigne reported in “Apology for Raymond Sebond” that the philosopher Cleanthes once observed the negotiation between two different anthills. After some bargaining, the body of a dead ant was ransomed for a worm.

Rev. J. G. Wood, in his extremely popular collection of animal anecdotes entitled Man and Beast (1875), gave this report of a lady that had killed several ants: “After a while, one more (ant) came, discovered his dead companions and left. He returned with a host of others. Four ants were assigned to each corpse, two to carry it and two to walk behind. Changing tasks at times so as not to become weary, the ants eventually arrived at a sandy hill where they dug graves and buried the dead. About six ants, however, refused to help with the digging. These were set upon by the rest, executed and unceremoniously thrown into a mass grave.”

Anthills are like metropolises or vast armies, and people can almost never distinguish between individuals. Perhaps, though, even ants can have their nonconformists. The Disney animated film Antz told of one ant named “Z,” who was unable to work or dance in the same way as the others. Gradually, he moved the workers over to his style of thinking. He saved the colony from a flood and married the princess. Did they live happily ever after? They started having millions of children, but their anthill did not seem greatly changed. Perhaps the movie was about the loosening of social restraints in the West during the late sixties. “Revolutions may be fun,” the message seemed to be, “but don’t expect too much! Just like ants, we are ruled by our genes.”

Nothing we can say about ants is ever quite right. They are not really “communist” or “authoritarian.” They don’t really even have “workers,” “soldiers,” “slaves,” or “queens.” As scientists discover more about these creatures, the experience of ants only becomes harder to imagine. French author Bernard Werber took up the challenge in his novel The Empire of Ants. The ants, he explained, communicate mostly by scent, using pheromones, so they are like one enormous mind spread across the globe. A young female ant, separated from her community, set out to found a new anthill. She explored the world of a yard, filled with beetles, termites and birds, until finally she became queen of one vast colony that was powerful enough to challenge human beings.

Well, ants really do not threaten us, but their society will almost certainly outlast humankind. Ants thrive everywhere, from the Brazilian rain forests to the tiny cracks between the pavements in New York. Though they may appear frail, ants are able to survive even nuclear tests. In the Renaissance, an ant was sometimes depicted devouring an elephant to show the changeable nature of all things.

BEETLE

The poor beetle that we tread upon

In corporal sufferance finds a pang as great

As when a giant dies.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Measure for Measure

Beetles are often found near garbage, around excrement, and in dank, moist areas. People usually associate beetles with filth, squalor, and decay, but we can think of these environments as “compost” that will soon nurture life.. In the ancient Mediterranean region, people believed that living beings, particularly insects, sprang spontaneously from decomposing matter, and a few varieties of beetles came to be regarded as holy.

Foremost among these is the scarab beetle, also known as the “dung beetle,” which has been represented in countless amulets, some of which were found wrapped in the cloth covering mummified corpses. The scarab lives off dung and is frequently seen near farms. It pushes a globe of dung to an underground burrow before consuming it, and to the ancient Egyptians the ball suggested the sun crossing the sky. The scarab was sacred to Ra, god of the sun. The god Khepera, associated with creation and immortality, was depicted with the head of a scarab beetle. The female scarab beetle also lays her eggs in a ball that she creates inside her hole. The Egyptians confused the two processes of feeding and reproduction in scarabs, thinking the eggs hatching from the ball were generated spontaneously from the earth.

The Egyptians held a number of other beetles sacred as well. One long slender click beetle (Agypus notodonta) was sacred to Neith, a very ancient goddess associated with both fertility and war, and it was often depicted on amulets and hieroglyphs. In the later periods of Egyptian civilization, including the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, beetles were mummified and placed in miniature sarcophagi, in the expectation that they would enter the next world. According to Charbonneau-Lassay, the veneration of certain beetles eventually spread from Egypt to much of the area around the Mediterranean. It also spread south to sub-Saharan Africans, who revered the golden-tinted rose beetle up through at least the eighteenth century.

One brightly colored insect, usually orange with black spots, is known as the “ladybug” in the United States and the “ladybird” in Britain. “Lady” can refer to the Virgin Mary. In France, the insect is sometimes called “poulette à Dieu” or “chicken of God.” These names and the regard with which the insect is viewed hint at a divine role in religions of antiquity, but this has never been fully explained. One theory is that the beetle was once sacred to Freya, the Scandinavian goddess of love. The association of the ladybug with the sun, however, indicates that its cult may be connected with that of the Egyptian scarab.

To have a ladybug alight on your clothes is considered a sign of good fortune, but you must never kill or injure the creature. You are to send it away with a rhyme, though you may also hurry it along with by blowing gently. In one common the British variant this goes:

Lady Bird, Lady Bird,

Fly away home,

Your house is on fire,

Your children will burn.

The verse may possibly refer to the ladybug’s association with the sun, which could be partly due to the bright red on its back. Another theory is that the lines could refer to the burning of hop vines after harvest to clear the fields. Sometimes, if the request is made in additional verses, people have believed the insect will fly to one’s sweetheart.

In traditional rural societies, the cycle of putrefaction and renewed life was evident in yearly routines such as fertilizing the land, but it is experienced less intimately in Western cultures today. The beetle, a form of “vermin,” sometimes appears as a symbol of unredeemed filth. In the novella The Metamorphosis by the German-Jewish writer Franz Kafka (1915), a traveling salesman named Gregor Samsa, subject to degrading demands from both family and work, woke up one day to find he had been changed into a giant insect. Many readers take it for a cockroach, which is now perhaps most intimately associated with squalor and decay. The creature in Kafka’s story is indeterminate, but the description of the insect lying on its hard back with legs kicking helplessly in the air suggests a beetle. By accepting his martyrdom, to die neglected and be thrown out in the trash, without resentment, Gregor becomes a Christ-like sort of figure.

SCORPION

Do not forget Yahweh, your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery: who guided you through this vast and dreadful wilderness, a land of fiery serpents, scorpions, thirst …”

—DEUTERONOMY 8:15

Since the scorpion is found in cracks, crevices, holes, and enclosed places, it is often associated with chthonic deities. Much like a snake, it can often strike unexpectedly. Its sting can be very painful and sometimes deadly. The scorpion can be a symbol of evil, but also an instrument of divine retribution.

This dual symbolism is already found in ancient Egypt. The god Set, evil brother of Osiris, attacked the infant Horus in the form of a scorpion, no doubt a familiar sort of experience to the ancient Egyptians since children were particularly vulnerable to the sting of this animal. The divine infant was saved by the medicine of Thoth, god of knowledge. Selket, a goddess of marriage, fertility, and the underworld could, however, also use the power of the scorpion to fight demonic powers. She was often depicted with the body of a scorpion and the head of a woman, sometimes also as a scorpion holding an ankh, the Egyptian cross. In addition, she was painted as a woman with a scorpion on her head or in her hand, an image that the Romans eventually began to use as an allegorical representation of the African continent.

Selket, a scorpion-goddess of ancient Egypt.

Scorpion-man from an inlaid harp found in excavations of Ur, circa 2600 B.C.

The Hittite and Babylonian equivalent of Selket is the goddess Ishara, who is associated with love and with motherhood. In her honor, the scorpion first became a constellation of the zodiac among the Semitic peoples of Mesopotamia. Scorpion-men frequently appear in the art and literature of Mesopotamia. They usually have the heads of human beings, the wings and talons of birds, a serpent for a penis, and the tail of a scorpion. Sometimes they are associated with Tiamat, the sinister mother-goddess, but they are also attendants of the sun god Shamash and guard his realm against demons. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, a scorpion-man and scorpion-woman guard the mountain where the sun rises.

According to a Greco-Roman legend, the great hunter Orion boasted that he would kill all animals. On hearing that, the earth-mother Gaia summoned a scorpion, which bit his heel and killed him. Asclepius, the divine physician, restored Orion to life, but Zeus would not accept this interference in the process of life and death, and so he sent a thunderbolt that killed Orion a second time. Placed in the zodiac, the scorpion and Orion now represent death and life, whose eternal battle is enacted as the sun moves between the two constellations.

In China the scorpion was one of the five venomous animals, but images of it could help to keep demons or illness at bay. In Zoroastrianism, the scorpion was a creation of Ahriman, the power of darkness. In Mithraic religion, however, the scorpion became one of the animal companions of Mithras, as he sacrificed a great bull to regenerate the world.

In Christianity, the scorpion was often a symbol of the devil, waiting in ambush for unsuspecting travelers. Jesus told his followers, “Yes, I have given you power to tread underfoot serpents and scorpions …” (Luke 10:19). In the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, the tempter in Eden was sometimes depicted not as a serpent but as a creature with the face of a woman and the tail of a scorpion, an image which goes back to Selket. Some misogynistic moralists have compared the scorpion’s habit of hiding in holes to a woman who would hide perfidious intent behind a beautiful face.

SNAKE AND LIZARD

Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made.

—GENESIS 3:1

Snakes can have dozens of young at a time, and so they are often symbols of fertility. They resemble vegetation, especially roots, in their form and often in the green and brown of their skins. The undulating form of a snake also suggests a river. A point of muscular tension passes through the body of a snake and drives the animal forward, like a moment in time moving along a continuum of days and years. Like time itself, a snake seems to progress while remaining still. In addition, the body of a snake also resembles those marks with a stylus, brush, or pen that make up our letters. Ornamental alphabets of the ancient Celts and others were often made up of intertwined serpents. It could even be that the tracks of a snake in sand helped to inspire the invention of the alphabet. The manner in which snakes curl up in a ball has made people associate them with the sun.

According to one legend, Sakyamuni, who later became the Buddha, was once walking beside a cliff when he looked down and saw a great dragon renowned for wisdom. The seeker asked many questions, and the dragon answered all of them correctly. Finally, Sakyamuni asked the meaning of life and death. The dragon replied that he would only answer when his hunger had been stilled. Sakyamuni promised his body as food, and the dragon revealed the ultimate truth. Then Sakyamuni hurled himself into the open jaws of the dragon, which suddenly changed into a lotus flower that carried him back to the precipice. The snake (in this case, a dragon) is an eternal mediator between opposites: good and evil, creation and destruction, female and male, earth and air, water and fire, love and fear.

Since the snake does not have exposed sexual organs, it is very hard to tell the male snakes from the female ones. Serpents often represent a primeval androgynous state before the separation of male and female. In the ancient world, however, serpents were associated with a vast number of goddesses, including the Greek Athena, the Mesopotamian Ishtar, the Egyptian Buto, and many others. Serpentine divinities include the Babylonian Tiamat, a primeval goddess from whose blood the world was created. The pharaohs of ancient Egypt would wear the ureaus on their heads, a protective image of the goddess Wadjet in the form of a cobra, leaning back and ready to strike. For the aboriginal people along the northern coast of Australia, the rainbow serpent is the most important of spirits, and they see traces of it in the undulating rivers, valleys, rocks, and caves of their landscape.

As people turned more exclusively to patriarchal deities, there was a massive revolt against the cult of the snake. This is why serpents are so often destructive in the mythologies from very early urban civilizations. Egyptians believed that the serpent Apep would try to devour the boat of the sun god Ra as he sailed it through the earth every night. Serpents have been killed by just about every major god or hero of the ancient world, and many in Medieval times as well. The Babylonian Marduk killed the serpent goddess Tiamat, and Zeus killed the primeval serpent Typhon. Apollo, the son of Zeus, killed the serpent Python to gain the shrine at Delphi, formerly sacred to the goddess Gaia. As an infant in his crib, Hercules strangled two serpents to death. Cadmus, a legendary founder of Greek civilization, killed a serpent and then planted its teeth, from which sprang warriors; the ancestors of the noble families of Thebes. Sigurd, the Norse hero, killed the dragon Fafnir. Saint George—patron of England, Russia, and Venice—killed a dragon, while Saint Patrick drove the snakes out of Ireland. Even today in Texas, some communities have annual “rattlesnake roundups.” People festively collect rattlesnakes, tease them, and finally kill them for food.

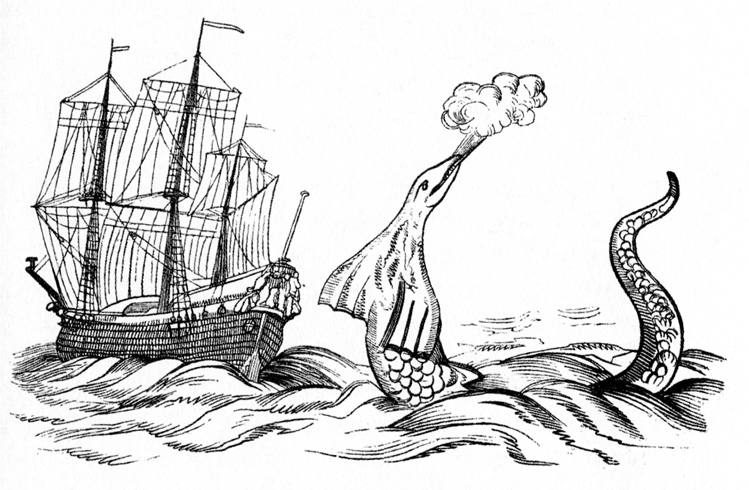

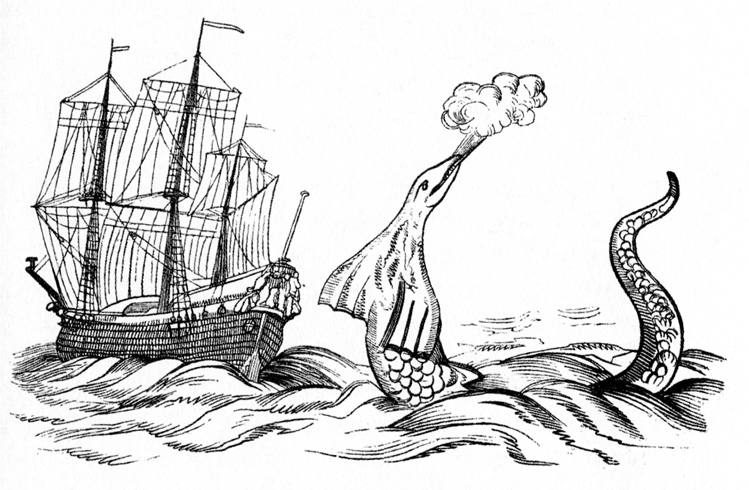

Drawing of a sea serpent reportedly sighted in 1743.

Images of the snake are often similar in cultures that appear to have little or no contact with one another. In Aztec mythology, the earth mother Coatlicue was a female serpent in a primordial sea. She is today especially well-known because of a monumental Aztec statue of her, dated from the fifteenth century CE. The statute, located in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, is one of the most terrifying images ever made. She has a double head; two rattlesnakes gazing at one another. She wears a skirt woven entirely of serpents, and a necklace of human hearts and skulls. According to Aztec myth, she gave birth, without prior intercourse, to many deities including Huitzilopochtli, the sun god, and Quetzalcoatl, the god of wisdom. In one story, her elder daughter, Coyolxauhqui was enraged at their birth, and, together with Coactlicue’s previous children, turned against her mother. Huitzilopochtli, emerging from the womb fully armed, then cut off Coyolxauhqui’s head and threw it into the sky, where it became the moon, while the siblings allied with her became stars. Coatlicue shares many features with Tiamat, including a terrifying visage, a close association with snakes, and an ability to conceive children without a partner. It is possible that they could both go back to a single mythology that arose before human beings had spread from Eurasia to the Americas.

After expelling Adam and Eve from Eden for eating from the tree of knowledge, Yahweh placed a curse on the serpent, which has ever since crept upon the ground. But just as the Biblical Yahweh—who can often be wrathful, jealous, and arbitrary—does not seem unequivocally good, so the serpent of Eden does not always appear fully evil. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the serpent of Eden was often painted with a human head, usually that of a woman: In Paradise Lost, Milton describes the serpent thus:

Woman to the waist, and fair,

But ended foul in many a scaly fold

Voluminous and vast, a Serpent arme’d

With Mortal sting.

At times, the serpent is a mirror image of Eve. Even in paintings in which the head of the serpent is bestial, the serpent and Eve often seem to be exchanging meaningful glances, while Adam simply looks confused. Eve and the serpent share a feminine wisdom. The serpent of Eden is also identified with Lilith, the first wife of Adam, who was also a Sumerian goddess-demon.

The large, intense eyes of the snake appear very mysterious. Pliny the Elder and countless subsequent writers have reported that snakes can hypnotize and even kill with a simple gaze. The basilisk, a serpent with a crown and wings, reportedly had this ability, as did the rattlesnake in the United States. Many authors from journalists and novelists to serious natural scientists reported that snakes could draw birds out of the sky by looking upward, and they sometimes even worked their powers of fascination on human beings.

The serpent has frequently been rehabilitated and even deified, especially by the Gnostics and the alchemists. Serpents are ancient symbols of healing. In the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the serpent steals the plant of immortality then sheds its skin and lives forever. Ancient physicians from Greece to China realized that venom extracted from certain serpents may be used to cure ailments such as paralysis.

Serpents are associated with the Greek healer Asclepius, who once raised a man from the dead. The ancient Greek physicians or “Asclepiads” had so much confidence in the healing powers of the serpent that they would sometimes place snakes in the beds of those with high fevers. They may have served as a sort of placebo, and the coolness of the serpents flesh could have convinced the sufferer that he was recovering. The Caduceus, a wand with two serpents entwined around it was carried by Hygeia, daughter of Asclepius, and by the god Hermes. Today it remains a symbol of the medical profession.

The alchemists saw the serpent as an animal that joined all of the four elements out of which the cosmos was formed. Of all animals, serpents are most intimately associated with the earth. This further associates them with fire, since that element escapes from the earth in volcanoes. The red tongue of many snakes, ending in a fork and flickering in and out, also suggests flame. Dragons, especially in European traditions, often breathe fire. Furthermore, serpents are also frequently found in water, and their rhythmic motion suggests waves. Many dragons and other serpentine figures are depicted with wings.

Among the most popular images among the alchemists was the ouroboros, a snake with its tail in its mouth, a symbol of primal unity. This goes back at least to the Egyptian Book of the Dead, written around 1,500 BC, and it was later taken over by the esoteric religions of Greece. An analogous figure is the serpent Midgard of Norse mythology, which is coiled around the earth. The Chinese used the “V” shaped fangs of a serpent to symbolize the essence of life, while upside down this represented the spirits of deceased ancestors.

From the point of view of folklore, lizards may generally be regarded as snakes, even though most (not all) lizards have legs. Because these animals are often found in lying in the desert sun, they have sometimes been associated with contemplative ecstasy. Pliny the Elder had reported, with some skepticism, that the salamander, a black and yellow lizard found in most of southern Europe, would quench flames with the coldness of his body. Paracelsus, an influential alchemist and physician of the Renaissance, believed that the salamander was a being of pure fire. The salamander sitting inside a furnace became a symbol of esoteric knowledge. It was compared to the three young Hebrews who were thrown into a fiery furnace by the king of Babylon but were not harmed by the flames (Daniel 3:22-97), and to Christ descending into Hell.

Even the Hebrews, who reacted so vehemently against the archaic cult of the serpent, have occasionally attributed godlike, supernatural powers to this animal. In the book of Exodus, Moses and Aaron were demanding of Pharaoh that the people of Israel be released from bondage. To demonstrate the power of his god, Aaron threw his staff down in front of Pharaoh and his court. It immediately turned into a serpent. At the direction of Pharaoh, the court magicians also tossed down their staffs, which became serpents as well, but Aaron’s serpent swallowed all the others. Later, on the journey to Canaan, the Hebrews were stricken by a plague of fiery serpents. Moses directed the people of Israel to erect a bronze serpent on a standard, and all those who look upon it were saved from death (Numbers 21:4-9). Were this not sanctioned by scripture, it would probably have seemed to the Jews like sorcery and idolatry. Among the most extravagant dragons of all was that which did battle with Saint Michel in the Biblical book of Revelations. It had seven heads, each bearing a crown and ten horns, and it swept a third of the stars from the sky with its tail.

A positive view of the snake has also frequently been preserved in folk culture. During the wanderings of Aeneas, after the fall of Troy, his father Enchases had died. Landing on the coast of Sicily, he began the funeral rites by pouring out wine, milk, and blood of sacrificial animals. Then he cast flowers upon the funeral mound and began his oration. He had barely begun to speak when, in the words of Virgil’s Aeneid:

… from the depths of mound and shrine a snake

Came huge and undulant with seven coils,

Enveloping the barrow peaceably

And gliding among the altars. Azure

Flecks mottled his back; a dappled sheen

Of gold set all his scales ablaze, as when

A rainbow on the clouds facing the sun

Throws out a thousand colors.

Aeneas paused,

Amazed and silent, while deliberately

The snake’s long column wound among the bowls

And polished cups, browsing the festal dishes,

And, from the altars where he fed, again

Slid harmlessly to earth below the tomb.

The snake was the spirit of his father, whom Aeneas would later visit in Hades. Romans would sometimes feed snakes at household altars.

The Scythians who lived by the Black Sea and were known for their fierceness traced their ancestry to the daughter of the Dnieper River, who was a woman above the waist but whose body ended in a serpent’s tail. Not only the ancient Romans but many also other peoples—for example, Australian Aborigines—have believed that ancestors return in the form of snakes. Legendary Zulu kings would also sometimes be reincarnated as powerful serpents.

Despite, or because, they are not easily distinguished by gender, snakes appear highly sexual, and there are many tales of serpentine paramours. One tale from the Hindu-Persian Panchatantra tells how a Brahman and his wife longed for children but had been unable to conceive. One day a voice in the temple promised the Brahman a son that would surpass all others in both appearance and character. A short time later, his wife did indeed become pregnant, but she gave birth not to a human being but to a snake. Her friends advised her to have the monster killed, but she insisted on raising the snake as her child, keeping him in a large box, bathing him regularly and feeding him with fine delicacies. At her urging, the Brahman even arranged for the snake to marry a beautiful girl, the daughter of a friend. The girl, who had a strong sense of duty, accepted the marriage and took over the care of the reptile. One day, a strange voice called to her in her chamber. At first she thought a strange man had broken in, but it was her husband, who had climbed out of the snakeskin and taken on human form. In the morning, the Brahman burned the snakeskin, so his son would not be transformed again, and then proudly introduced the young couple to all the neighbors.

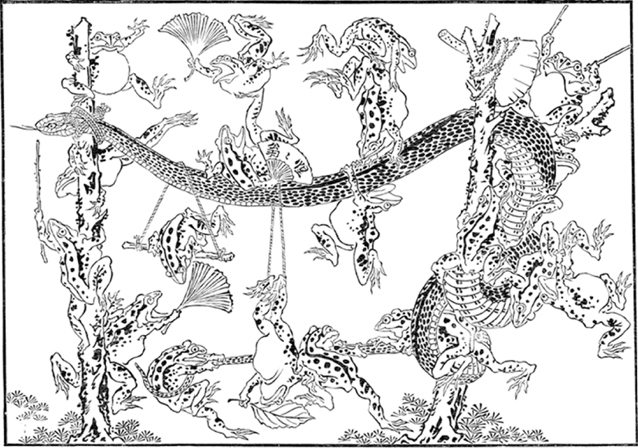

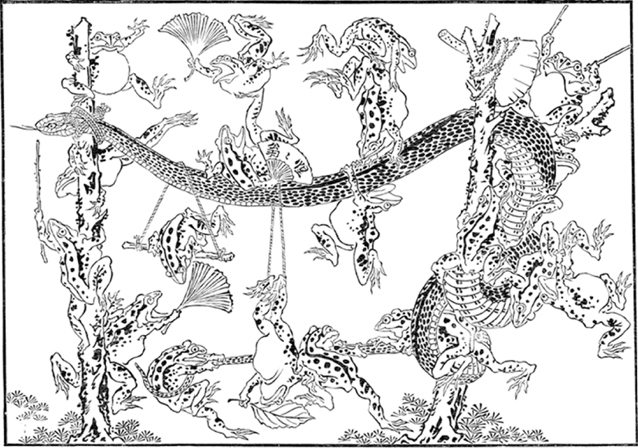

Frogs surround a snake in this illustration by Kawanabe Kyôsai.

Both snakes and dragons are designated by the same word, “draco,” in Latin. We can generally regard dragons as snakes, just as did zoologists of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Edward Topsell wrote in History of Four-Footed Beasts, Serpent and Insects (1657), “There be some Dragons which have wings and no feet, some again have neither feet nor wings, but are only distinguished from the common sort of Serpents by the combe growing upon their heads and the beard under their cheeks.” The variety and range of dragons vastly exceed those of any other mythic animal. Dragons often combine features of many animals, such as the wings of bats or horns of stags, but these are set upon serpentine forms. Just as it mediates between the elements, the snake seems to combine features of all creatures in its incarnation as the dragon.

In very archaic times, the serpent was almost universally revered in China. Into the twentieth century CE, several temples in southern China have followed the tradition of keeping sacred serpents that are offered wine and eggs on the altar. One popular legend tells that when Buddha was meditating prior to attaining enlightenment, a snake approached and wound itself around him seven times, and then guarded him for seven days from the other animals of the forest. Chinese culture gradually began to distinguish more sharply between the snake and the dragon, usually to the detriment of the snake, and they became opposites in the Chinese zodiac.

The Chinese dragon, known as “lung,” is among the most colorful and extravagant composites. When first born, it appears as a simple serpent. Over thousands of years of life, it acquires the head of a camel, the scales of a carp, the horns of a deer, the eyes of a hare, the tusks of a boar, and the ears of an ox. It also has four short legs with enormous claws, a mouth with long teeth, and a flowing mane running down its back. A combination of fire and steam issues from its nostrils to form the clouds, and so it controls the weather. By tradition, conception in the year of the dragon brings special blessings, and so Chinese communities always experience an increase of births around that time.

As the modern period began, people increasingly thought of the snake as masculine. The traditional eroticism of the snake was originally considered primarily a feminine attribute, and only later a male one. This view was sanctioned by Freudian psychology, where people have usually interpreted the snake as phallic. In James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the hero, Stephen Daedalus, calls his sexual organ “the serpent, the most subtle beast of the field.”

Legend usually locates fantastic beasts on the frontier of human exploration, and the serpent is a good example. With the expansion of maritime trade at the end of the Middle Ages, the Great Sea Serpent was second in importance only to the mermaid as a figure in the lore of mariners. Sightings of serpentine creatures were reported everywhere from Loch Ness in Scotland to the coasts of the New World, often attested by many people who had reputations for good judgment and sobriety. These were identified with many mythological creatures that ranged from the Norse Midgard Serpent to the Biblical Leviathan. While the descriptions differed in their details, they generally described the serpent as extremely long and as moving with an undulating motion. On August 21, 1936, for example, newspapers reported a monster seen by several Newfoundland fishermen that was at least 200 feet long, has “eyes as big as an enamel saucepan,” snorted blue vapor from its nostrils, and stirred up such waves that “for days no boat dared venture out to sea.”

The symbolism of the snake has changed far less fundamentally than that of other animals such as the dog or horse. It seems to surface whenever people contemplate origins, whether of humanity, of life, or even of the universe itself. Today, the DNA code that directs the development of the embryo is sometimes called “the cosmic serpent.”

WORM

I am a czar—a slave; I am a worm—a god.

—GAVIL DERZHAVIN

Through most of history, people generally have not distinguished sharply between earthworms, eels, and snakes. The word “worm” or “wurm” was sometimes used, in English and other Germanic languages, to designate a snake or dragon up through much of the nineteenth century. The earthworm, however, has never had the satanic glamour of serpents. With facial features that are difficult to see, earthworms are unusually hard to distinguish from one another. In consequence, they are seldom thought of as individuals, and, even in mythology and folklore, they rarely speak.

Worms have been associated since ancient times with moist, fertile earth. In Antiquity, worms were believed to be generated spontaneously from dirt, in part because they would appear after the rain. This primeval character was shown in a Mesopotamian incantation entitled “The Worm and the Toothache,” written in the second millennium BCE:

After Anu (god of the sky) had created heaven,

Heaven had created the earth,

The earth had created the rivers,

The rivers had created the canals,

The canals had created the marsh,

And the marsh had created the worm—

The worm went, weeping before Shamash (god of the sun),

His tears flowing before Ea (god of deep water):

What wilt thou give me for my food?

The gods first offered the worm a fig, but it refused and asked to be placed in the gums of a person.

In literature, a worm is usually a symbol of humble status. A psalmist, for example, has written, “Yet here am I, now more worm than man/ scorn of mankind, jest of the people …” (Psalms 22:6). The book of Isaiah concluded with an eschatological prophecy that God would make the heavens and earth anew. In the final words, God told the prophet how all people will come to worship:

And on their way out they will see

the corpses of men

who have rebelled against me.

Their worms will not die

nor their fire go out;

they will be loathsome to all mankind.

Worms eat corpses, so to live on as part of a worm was the destiny of all who failed to transcend the body.

In the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, Europeans became increasingly obsessed with physical decay, and worms symbolized the corruption of the body after death. Worms were often painted crawling in and out of a human skeleton. The following lines from Shakespeare’s Hamlet showed a noteworthy awareness of ecological cycles:

HAMLET: A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of the worm.

KING: What dost thou mean by this?

HAMLET: Nothing but to show how a king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar.

The worm, the most humble of animals, was always triumphant in the end, showing the ultimate equality of all living things.

Just as serpents are traditionally associated with moral corruption, worms are often connected with physical decay. Their habit of burrowing inside a fruit or flower has often impressed people as a botanical equivalent of demonic possession, and it can seem vaguely sexual. This is apparent in “The sick Rose,” written by William Blake in the last decade of the nineteenth century:

O Rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm

That flies in the night

In the howling storm

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

But the connection of worms with the earth could be restful as well as disturbing.

The very last study written by Charles Darwin before his death was entitled The Formation of Vegetable Mold Through the Action of Earthworms. Some scientists have regretted that the founder of evolutionary theory should have turned to such a specialized theme in the end, but the choice reflected his desire for bucolic peace. Darwin wished to show that earthworms, traditionally the lowest of creatures, were an essential part of the natural cycle. They improved the fertility of the soil and so are essential for the continued prosperity of other creatures, including humankind. With the growing ecological awareness in the latter twentieth century, earthworms increasingly symbolize the ultimate unity of all life. This is even apparent in the field of physics, scholars of which refer to discontinuities in time and space as “wormholes.”

HE FIRST FEW INCHES OF FOREST SOIL ARE WHERE BOTH THE DECAY OF organic matter and the regeneration of new life are most pronounced, and it is often hard to tell life from death. It is also a dwelling place of nature deities, such as Spider Woman in the mythology of the Navaho and Hopi Indians. In many highly formalized religions, especially the Abrahamic ones, the realm beneath the ground is Hell, where demons torment, cook, devour, and excrete sinners. For the fifteenth century CE alchemist Paracelsus, often considered “the father of modern medicine,” creatures of the earth (also called “earth elementals”) were “gnomes.” Our ground is their air, and they can see and walk through it. They are very small yet basically human in form, but, like people, they can have deformed births, which might take all manner of strange shapes. Fanciful as this may be, it does in ways describe life in the topsoil, where beetles and centipedes bore through the ground as easily as we walk over it.

HE FIRST FEW INCHES OF FOREST SOIL ARE WHERE BOTH THE DECAY OF organic matter and the regeneration of new life are most pronounced, and it is often hard to tell life from death. It is also a dwelling place of nature deities, such as Spider Woman in the mythology of the Navaho and Hopi Indians. In many highly formalized religions, especially the Abrahamic ones, the realm beneath the ground is Hell, where demons torment, cook, devour, and excrete sinners. For the fifteenth century CE alchemist Paracelsus, often considered “the father of modern medicine,” creatures of the earth (also called “earth elementals”) were “gnomes.” Our ground is their air, and they can see and walk through it. They are very small yet basically human in form, but, like people, they can have deformed births, which might take all manner of strange shapes. Fanciful as this may be, it does in ways describe life in the topsoil, where beetles and centipedes bore through the ground as easily as we walk over it.