he seashore has long been a place of wonder, where one can still find colorful stones, shells, bits of coral, smooth fragments of glass, and the relics of all sorts of strange and wonderful events beneath the waves. A few creatures such as turtles and seals are almost (though not quite) equally at home in two realms, earth and water; others, such as gulls, add the third realm of air. Often, the seashore symbolizes the intersection of time and eternity. In folklore, it is the abode of shape-shifters such as seals and swans, which cast off their skins to become human, and may then marry men or women.

he seashore has long been a place of wonder, where one can still find colorful stones, shells, bits of coral, smooth fragments of glass, and the relics of all sorts of strange and wonderful events beneath the waves. A few creatures such as turtles and seals are almost (though not quite) equally at home in two realms, earth and water; others, such as gulls, add the third realm of air. Often, the seashore symbolizes the intersection of time and eternity. In folklore, it is the abode of shape-shifters such as seals and swans, which cast off their skins to become human, and may then marry men or women.

The seal and dolphin might have been included here, but, since they also inhabit the depths of the sea, they will be found in Chapter 7 on “Mermaid’s Companions.”

SEAGULL AND ALBATROSS

At length did cross an Albatross,

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.

—SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Mariners traditionally observe seabirds closely, since the behavior of these creatures can tell them about subtle changes in the weather or their distance from land. Interpreting the flight and calls of avians, however, is a fairly intuitive art in which it is still often hard to distinguish reasonable calculation from superstition. The flight of birds can legitimately tell sailors a lot about things like the strength of winds or the distance from land, but it can also inspire daydreams.

Seagulls are remarkable flyers, able to ascend to great heights or hover on the wind. The ability of seagulls and related birds to glide on currents of the wind while remaining almost motionless makes them resemble a cross, the symbol of Christ, when seen from below. These birds follow ships, as though drawn by some kinship with human beings. Their calls are loud and confident yet also plaintive. Gulls and other sea birds can also easily appear to be spirits, especially when their white feathers are seen at night against a dark sky. Sailors from at least Medieval times to the present have believed that gulls, albatrosses, and stormy petrels were the souls of those drowned at sea. Three gulls flying overhead together are an omen of death. To kill an albatross or gull brings bad luck, and the fisherman should immediately release any bird caught in his net. Should a seagull fly against the window of the sailor’s house while he is away, it is a sign that the master is in danger.

Ovid wrote that once, when the goddess Venus, the Greek Aphrodite, had appeared on the fields before Troy, the impetuous Greek hero Diomed wounded her. Later, as he returned home after victory, his boat was tossed about by terrible storms. The sailors knew this was the vengeance of Venus. One hotheaded crew-man named Acmon heaped his scorn on the goddess and challenged her to do her worst. His companions rebuked him, and he tried to answer. The words did not come, for his voice had grown thin; his mouth had become a beak, and his arms were covered with feathers. He and his companions had been turned into white birds, gulls and their various relatives. In The Golden Ass by Apuleius, a gull would fly about the world to bring back news to Venus.

Ovid also wrote in his Metamorphoses that when Ceyx, king of Thrace, was preparing to journey by sea to consult an oracle, his wife Alcyone was seized by foreboding. She pleaded with him to remain. She reminded him of the shards of ships washed up on the shore. When Ceyx insisted on leaving, she begged to accompany him, for, she said, should the ship go down in a storm, at least they would lie together. After a long pause, Ceyx refused, promising to be home again within two months’ time. The premonitions of Alcyone proved true, and the ship went down in a terrible storm. Juno, the goddess of marriage, sent a dream of Ceyx to Alcyone. Her husband appeared naked and pale, and water flowed through his hair and beard. She woke and ran to sea by the light of dawn. In the distance, she could see a body. As it floated towards her, she slowly recognized her husband. As Alcyone ran to him, her feet skimmed over the surface of the sea; her arms changed into wings, her nose into a beak. Ceyx rose from the sea, and the couple became a pair of birds. Since that time, the winds and sea stay calm for seven days in winter as Alcyone nests on the surface of the waters. Ovid does not identify the birds, but tradition makes the wife a halcyon, a half legendary bird mentioned by many authors from Homer on, which scholars believe was a mythologized kingfisher. The name “Ceyx” means “tern,” but Ovid was far more interested in vivid tales than in ornithology, and he may have thought of both husband and wife simply as any seabirds.

The albatross is reportedly able to predict the weather. In Japan the albatross is a servant of the sea god and, therefore, auspicious. In the west, however, an albatross following a ship has been considered a herald of storms. In Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the narrator killed an albatross that accompanied the ship, apparently on a perverse impulse but perhaps also to evade a tempest. His ship was then stopped by a terrible calm, and the crew draped the dead albatross about his shoulders as a cross. Only when he had learned to love his fellow creatures did the bird fall from his neck, and the ship begin to move.

SWALLOW

True hope is swift and flies with swallow’s wings …

^WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Henry V

The swooping, gliding motion of a swallow as it catches insects in flight, together with its incessant calls, can at times appear melancholy. In much of the world, people think of the swallow as a joyful bird, since its presence announces the coming of spring. Since the swallow often makes its nest in crannies of buildings, it has always been on intimate terms with human beings. In France and other parts of Europe, rural people have often believed that the nest of a swallow would protect their homes. For Romans, swallows represented the penates or household spirits. Sometimes swallows were believed to be spirits of dead children, and people were not permitted to kill them. Swallows are almost perpetually in the air, so much so that Medieval people thought they did not have feet. Partly for that reason, they have always been considered very spiritual.

Swallows were often depicted on Egyptian mummies, suggesting they were already associated with resurrection. In an ancient love poem from Egypt, quoted by Dorothea Arnold, a young woman returns from her lover:

The voice of the swallow is speaking.

It says:

Day breaks, what is your path?

(The girl answers) Don’t little bird!

Are you scolding me?

I found my lover on his bed,

And my heart was sweet to excess.

The poem shows a remarkable resemblance to the “songs of dawn” by Medieval minnesingers and troubadours, in which lovers would often be awakened by a lark or other bird.

Plutarch related that, when Isis had retrieved the coffin of Osiris, she flew about his body and lamented in the form of a swallow. In Italian legend, when Mary stood before the Cross, swallows saw her distress and came to comfort her. They swooped down, coming ever closer, until finally they began to touch her in passing with their feathers. As they turned, the tears of Mary landed on their breasts and turned them from black to white. Swallows have frequently been portrayed darting about Christ as he lay on the cross. According to Swedish legend, they fanned him with their wings. For devout Christians, the appearance of swallows traditionally suggests the resurrection. Insects, especially flies, have often been associated with the Devil, and swallows, like agents of God, would relentlessly pursue bugs and snatch them up in flight.

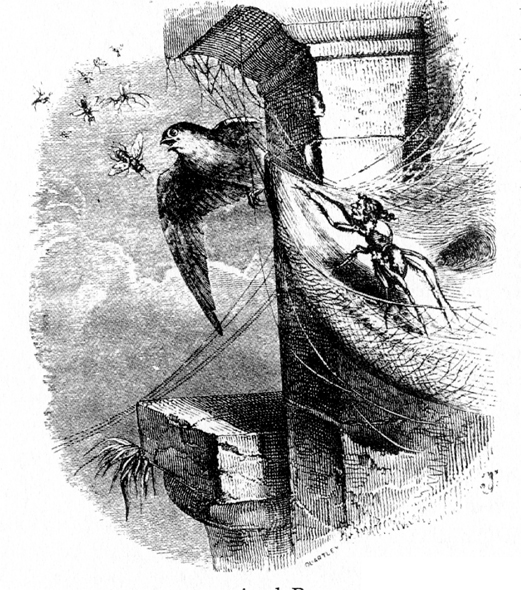

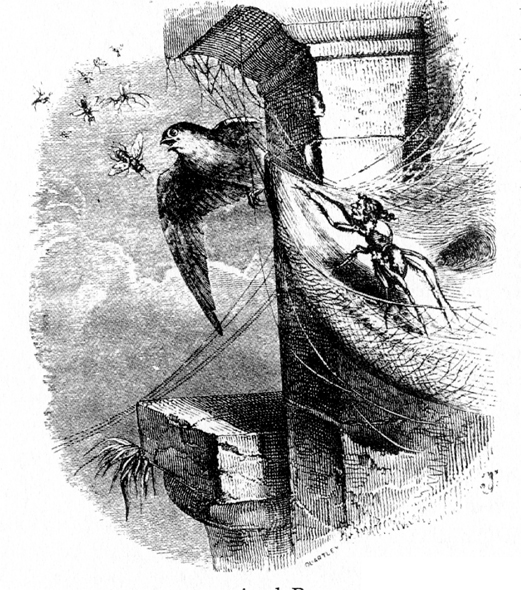

The swallow and spider compete for a fly.

(Illustratiion by J. J. Grandville, from Fables de la Fontaine, 1839)

People have always watched for swallows as a sign that winter was at an end. A fable recorded by the Hellenized Roman Barbius told of a young man who saw a swallow, thought that spring was coming, and decided to wager his winter clothes on a throw of the dice. After he had lost, a snowstorm came, and he soon saw the swallow lying dead from the cold. “Poor creature,” he said, “you fooled both yourself and me.” This tale may be the origin of the famous saying “One swallow does not make a spring.”

In part because the trajectories of their flights resembled those of bats, many Europeans have believed swallows hibernated in caves. In a famous letter of August 4, 1767, the British pastor and naturalist Gilbert White made one of his rare mistakes. After a large fragment of a chalk cliff had fallen during one winter in Sussex, England, many swallows were reportedly found dead in the debris. Though a bit skeptical of the account, White thought the dead swallows might have been in hibernation. About six and a half years later, White observed that the first swallows of the year were usually seen near ponds and that they disappeared in the event of frost. He suggested that the birds lay dormant through the winter under water. A few naturalists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries even believed that swallows sojourned on the moon. In Muslim countries swallows have traditionally been considered holy, on the ground that they make a yearly pilgrimage to Mecca. Their migratory paths were not actually mapped out until the nineteenth century.

DUCK, GOOSE, AND SWAN

But now they drift on the still water,

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake’s edge or pool

Delight men’s eyes when I awake some day

To find they have flown away?

—W. B. YEATS, “The Wild Swans at Coole”

Swans, geese, and ducks are aquatic birds, which appear more comfortable on water or in the air than on land. They tend, however, to congregate along the shore, since that is where food is most plentiful. If a stranger approaches a pond, they may all rise in unison. Because they often act in concert, they seem to have a sort of solidarity across lines of species. In Sanskrit, a single word, hansa, was used to designate all three varieties of birds. Nevertheless, their personalities in folklore have become very distinct. The swan is poetic, solitary, and often tragic in myth and legend, perhaps because of its white plumage and extraordinary grace. The duck is generally not alone but found together with its mate and children. The folkloric goose is more gregarious and earthy, and it is often part of a noisy flock.

These birds had considerable religious significance in prehistoric times. Throughout Eurasia and the Near East, there are many myths of the world being hatched from a cosmic egg. The Egyptians, for example, believed that Ra, the god of the sun, had emerged from the egg of a goose. Many ancient figurines have been found combining the features of water birds, such as elongated necks and beaks, with those of human females. Several scholars such as Marija Gimbutas have speculated about the worship of a bird-goddess in Neolithic times.

The Aspares of archaic Hindu mythology are water nymphs that transform themselves into waterfowl, and are perhaps early versions of swan maidens, which are such important figures of Eurasian folklore. There are countless stories, especially in Scandinavia and other lands in the far north of Eurasia, of water birds which become women and marry into human society, only to leave their husbands, resume their old form and fly away. Jacob Grimm and many other scholars have connected the swan maidens with the Valkyries, the warrior women of Norse mythology who appear in the sky to lead those slain on the battlefield into Valhalla.

Zeus took the form of a swan to seduce the maiden Leda, who then gave birth to the heroic twins Castor and Polydeuces. Leda herself, however, may once have been a swan deity. According to some versions of the legend, she laid two eggs. From one egg hatched the twins and from the other Helen of Troy. According to yet another version of the tale, given by Apollodorus, Nemesis, the goddess of fate, tried to escape the amorous attentions of Zeus by turning into a goose, but the god changed into a swan and raped her. Nemesis laid an egg, which was found by a shepherd in the woods and brought to Leda, who placed it in a chest. Helen eventually hatched from the egg, and Leda raised her as a daughter.

The swan was sacred to the Greco-Roman sun god Apollo, and it appeared on Greek coins as early as the third century BC. In early Greek religion, people sometimes believed that swans drew the chariot of Apollo across the sky each day, though horses later replaced them. The Greek philosopher Plato was known as the “swan of Apollo.” Socrates, according to tradition, had once dreamed that a fledgling swan had flown to him from an altar consecrated to love, rested for a while on his knees, then flew away singing beautifully. As he finished relating the dream, Plato was introduced to him, and Socrates knew immediately that this boy had been the swan. Just before his death, Plato dreamed that he was a swan flying from tree to tree as people tried in vain to catch him. Simmias, a former companion of Socrates, interpreted the dream to mean that many would try to grasp his spirit yet no interpretation would capture the full meaning of his words.

Traditional Chinese motif of ducks as symbol of conjugal love.

A very widespread legend—found in Aelian, Pliny the Elder and many other writers of the ancient world—is that swans sing a supernaturally beautiful song as they die. In the late Middle Ages, the swan pierced with an arrow and singing as it swam became a symbol of the house of Lusignan in France. Swans were especially linked with death in Irish mythology, in which they were the form taken by lovers to cross the boundary between earthly existence and the Otherworld. In one myth, Oenghus, the god of love, fell in love with a maiden named Caer. She changed into a swan on the feast of Samhain (November 1), and flew to join him. He also became a swan, and together they flew around a village three times and sang the people to sleep. The term “swan song” is still used to describe a final, valedictory achievement.

In another popular Irish legend, when Lir had been deposed as ruler of Ireland, he married Aev, and together they had three boys and one girl. A short time afterwards, however, Aev died. Lir remarried, this time to Aoife, Aev’s sister. The stepmother could not bear the way everyone admired the four children, since they were not her own. One day, as the children were bathing, Aoife took a magic wand and transformed them into swans. The girl Fionnula, eldest of the siblings, begged Aoife to give them back human form. Aoife would not relent, but at last she agreed to place a limit on the enchantment. She let the children retain human voices, and ordained that they must wander the desolate islands for nine hundred years before they would again become human. When the allotted time was almost up, they passed Saint Mackevig, a follower of Saint Patrick, on the remote island of Innis Gluaire. Mackevig heard the children singing as they swam by, marveled at their voices and wished to win them for his choir. After much searching, Saint Mackevig found the children or Lir, and led them into his chapel. When the bell rang for communion, the curse ended. In place of the swans were four ancient human beings. Saint Mackevig had just time to bless them and baptize them before they died.

The story of Lohengrin, the swan knight, is a sort of swan maiden story with the genders reversed. It was included in the epic Parzifal and many other Middle High German manuscripts, and the Grimm brothers eventually included several versions in their collection of German legends. Though often embellished with colorful details, the essential story is as follows. Duchess Else of Brabant was pressured to marry, but she had rejected her suitors. One day the knight Lohengrin sailed down the Rhine River is a boat drawn by a swan. Else received him, and the two soon fell in love, married, and had children. Lohengrin defended the kingdom valiantly, but he warned his wife never to ask about his origins. One day, thinking that her children should know about their father, she inquired about Lohengrin’s family in a moment of forgetfulness. The knight then returned to his swan-drawn boat and sailed away, never to be seen again.

The pristine white plumage was, for centuries, a fundamental characteristic of swans in the European imagination, but black swans were discovered by English settlers in Australia around the end of the eighteenth century. Whiteness had always been identified with goodness and purity, and so very the very existence of black swans challenged the bird’s traditional symbolism. Economist Nassim Nicholas Taleb has coined the expression “black swan,” used to refer to any event that is not predictable but has an enormous impact. In his words, “… almost no discovery, no technologies of note, came from design and planning—they were just black swans.”

Perhaps people were too intimidated by the poetic magnificence of swans to ever domesticate them very successfully. The cackling of geese, however, has been heard constantly on farmyards since ancient times. Since they become excited and honk noisily at any disturbance, they alert people to any threats. For this reason, they were thought of as protectors of the home. Geese were sacred to Hera, the Greek goddess of marriage, and to her Roman counterpart Juno. They were often kept in temples. When the Gauls invaded Rome in 390 and were scaling the Palatine Hill by night, the dogs remained silent, while the geese alerted the defenders and saved the city. According to Aelian, the event was commemorated yearly in Rome by a celebration in which a dog was sacrificed but a goose was paraded in a litter.

There are many tales of a goose that laid golden eggs, the best known of which comes from the fifth-century Roman fabulist Avianus. A farmer had such a magical bird, but he became impatient waiting every day for golden eggs. Finally, he decided to kill the goose, expecting to obtain the entire treasure all at once. Cutting it open, he found, to his distress, absolutely nothing inside. The moral is to be thankful for what you have and not to demand more.

People have distinguished sharply, however, between domestic geese and their wild counterparts, whose migratory habits remained unknown until modern times. In 1187, Giraldus Cambrensis, who explored the coasts of Ireland, stated that wild geese hatched from shells that clung to driftwood. Later authors reported that they grew on trees near the edge of the sea, and they were called “barnacle geese” or “tree geese.” The famous botanist John Gerard wrote in his 1597 Herbal that he had come across several of these shells on an old, rotten tree, and taken them apart to find avian embryos in various states of development. These reports enabled people of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance to classify wild geese as fish rather than as meat, which meant they could be eaten on Fridays and during Lent.

Male authors from the Renaissance through the Victorian period tended to view women as being either utterly wild or completely domestic, and they had much the same attitude towards geese. Unlike swans or ducks, geese have always been thought of as feminine, in part because their incessant chatter made misogynistic men think of gossipy females. Charles Perrault gave Tales of Mother Goose (1697) as an alternative title of his famous collection of fairy tales. The frontispiece to the first edition showed an old woman spinning as she told tales to children. Since then people have debated the identity of Mother Goose, if indeed she were an actual person at all. However that may be, the designation “Mother Goose” soon came to refer to an archetypal teller of stories, a bit like Aesop in the ancient world. From at least the latter part of the eighteenth century, English and American nursery rhymes have been known as rhymes of Mother Goose. This apocryphal author has been depicted as a goose, at times wearing a bonnet like an old-fashioned nursemaid or housekeeper, or even as riding a huge, flying goose.

All water birds are monogamous. While swans and geese marry human beings in folklore, ducks appear content with their own kind. This is in part because, unlike swans and geese, male and female ducks are usually very distinct from one another in appearance. Ducks are beloved in the Orient for the variety and splendor of their plumage. Mandarin ducks are Chinese symbols of conjugal fidelity, and to kill them brings bad fortune. Lafcadio Hearn has retold a Japanese story of a hunter named Sonjo, who came upon a mandarin duck couple in the rushes, killed the male, cooked him, and ate him. That night, he dreamed that he saw a beautiful woman weeping bitterly. She noticed Sonjo, reproached him for killing her husband, and told him to go again to the rushes. The next morning, the female duck swam straight towards him, tore open her breast with her beak, and then died before his eyes. Sonjo was so shaken that he gave up hunting and became a monk.

In the West, ducks have become affectionate symbols of the modern bourgeoisie, who value domestic peace more than poetry or heroism. Hans Christian Andersen contrasted traditional and modern values, to the detriment of the latter, in his famous tale “The Ugly Duckling.” One egg of a mother duck is slow in hatching; the chick that finally comes out is oddly proportioned and unusually large. It is not accepted by the other ducks, eventually rejected even by its own mother, and forced to wander about alone. Finally, the lonely bird flies up to join a flock of glorious white swans, fully expecting them to attack him; instead, they immediately welcome him to their flock. Looking at its reflection in the water, the bird finally realizes that it had been hatched from the egg of the swan, which had been laid among the ducks. The theme, a common one in the Romantic Movement of the early nineteenth century, was the suffering of the poet in the prosaic world of the middle class.

By the latter nineteenth century, swans were featured less in literature than in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet such as Richard Wagner’s “Lohengrin” and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake,” where they evoked a past of wonder and heroism. In Henrik Ibsen’s drama “The Wild Duck,” a wounded, wild duck, rescued by a young woman and confined to a barnyard, symbolizes the frustrations of domestic life.

Though the swan was favored in heraldry, the duck is far more prominent in popular culture of the modern age. Rubber ducks for the bathtub are among the most beloved of children’s toys; wooden ducks are used by hunters as decoys and to decorate the mantelpiece. The most popular duck of all is Donald, who has been the subject of innumerable cartoons and comic books since the 1930’s. He shows all the neurosis and insecurity of the middle classes. He is perpetually jealous of his companion Mickey Mouse, and is forever getting into trouble. All of this makes him easy to identify with in our relatively unheroic age, and, besides, he is usually pretty successful in the end. In Europe, he now far surpasses Mickey in popularity.

TURTLE AND TORTOISE

I am related to stones

The slow accretion of moss where dirt is wedged …

—ANTHONY HECHT, “Giant Tortoise”

Tortoises are generally larger than turtles and spend more time on land, but people did not even make a rough distinction between the two until the sixteenth century. The word “turtle” is still sometimes used as a general term for both, and that is how we will use it here. The folkloric reputation of the turtle as a primeval creature has, in some respects, found surprising confirmation by scientists. They have existed for about 230 million years, and individuals of some species can live over two centuries.

The wrinkled features of turtles suggest age, while their silence can give the impression of wisdom. Though not very fast even in the water, turtles have great strength and stamina. The shell of a turtle often represents the cosmos, with a dome for the sky and a flat surface beneath for the earth. When the turtle emerges from a shell, it can appear as new creation, while withdrawal into the carapace can seem like reversion to the beginning of the world.

Mythologies throughout the world have associated turtles with the primordial waters out of which the earth was formed. Turtles have often been used as symbols of fertility, since they are constantly seen copulating in ponds in spring. Furthermore, the head of a turtle emerging from the shell can suggest a phallic symbol. On the other hand, the resemblance of the carapace to a womb has moved people in some cultures such as the Chinese to think of turtles as primarily feminine.

Oppian, writing in Greek during the second century CE, believed that female turtles were always unwilling sexual partners and had to be raped by the males in order for the species to reproduce. Several modern observers have shared this impression, but it is hard to tell the feelings of turtles during copulation or at any other time. The apparent detachment with which turtles copulate helped make them symbols of chastity in the Christian Middle Ages.

In Greek mythology, the god Hermes, as a mischievous infant, invented the first musical instrument, the lyre, from a carapace. He saw a mountain tortoise grazing in front of a cave, and, perhaps thinking of the echoes in a cavern, killed the animal and strung the guts of sacrificed bulls across the shell. He later gave the lyre to the god Apollo in payment for stolen cattle. Perhaps in lost versions of the story, a nymph was transformed into a tortoise, so that she might escape the amorous advances of the god, much as Syringa was transformed into reeds when fleeing Pan. The lyre itself seems feminine, and playing it can easily suggest a sublimated sexuality. This would explain why it seemed inappropriate for Hermes to keep the instrument as his emblem.

According to legend, the I Ching, a Chinese system of divination, began in the early third millennium BCE as the fabled Emperor Fu Hsi was walking along the Yellow River and saw a turtle emerge from the waters. The sage ruler saw eight trigrams on the back of the turtle—that is, eight groups of three lines, either solid or broken, each. He interpreted these signs as patterns of cosmic energy that might be used to divine the future. Historians believe the I Ching may have actually been developed from a practice of divination that used the cracks in a tortoise shell exposed to intense heat.

A symbol carried on banners by the imperial army in China was a serpent wound around a turtle, though this image has been variously interpreted. Sometimes it has been taken as a struggle between the might of the serpent and the indestructibility of the turtle, in which neither party can be victorious. In another view, the serpent was male (or “yang”), while the turtle was female (or “yin”), and the two were engaged in copulation. It is not unusual, however, in East Asian cultures to have opposites such as strife and harmony represented by a single symbol.

In one very ancient story from Japan, known in many versions, a young man named Urashima was fishing all alone on the wide sea for three days yet had managed to catch nothing, when he felt a weight in his net and hauled up a multicolored turtle. As he lay down to sleep, the turtle suddenly changed into a beautiful young woman. She explained that she lived in heaven as a star of the Pleiades (or, in some retellings, dwelt beneath the sea) and had fallen in love with him. Urashima ascended with her to a heavenly mansion where they were married and lived together in happiness for three years. Then, for all the joys of his new life, Urashima began to miss his parents and begged his wife to allow him to visit them once more. She very reluctantly agreed, and gave him a box as a parting gift, telling Urashima to grip it firmly if he wanted to return, but to never open the lid. On returning home, Urashima found that the village was changed and his parents were long dead. He had failed to realize that a year in heaven was a century on earth. In panic, Urashima seized the box, thoughtlessly opened it, and instantly turned into a very old man, for the box contained all of the years he had spent in the celestial kingdom.

The second avatar of the Hindu Vishnu was as the turtle Kurma, who served as the base of the mountain Mandara, where it churned an ocean of milk for the deities, thus producing the nectar of immortality. According to some Hindu traditions, the world rests on the back of an elephant, which, in turn, is standing on a turtle. The idea that the world rests on a turtle’s back is also found in the mythologies of several Native American tribes, especially those of the Eastern woodlands. According to a tale of the Huron Indians, variants of which have been recorded in many other tribes, the goddess Aataentsic, who lived in the clouds, split the tree of life with her ax. Part of the tree fell through a hole in the sky; Aataentsic, fearing that all life might perish, jumped down after it. At that time there was no earth but only water. When Turtle looked up and saw Aataentsic falling, he directed Beaver, Muskrat, Mink, and Otter to dive down and bring up earth from the bottom of the ocean. The animals placed the earth on Turtle’s back to provide a cushion, so Aataentsic settled down and the tree took root. The Lenape and other tribes also have a myth that the earth was once covered by a great flood and human beings sought shelter on the back of a turtle.

In Africa, the turtle is a trickster figure, yet, unlike other tricksters such as the Native American coyote, he is virtually never impetuous. The slow movements of the turtle suggest caution, and its wrinkled face suggests the wisdom that comes with age. Other tricksters often become victims of their own cleverness and pride, but the turtle is prudent and almost always victorious. In one widely told West African story, which has also been recorded in the United States, a lion captured and tried to devour a turtle. The captive told the king of beasts, “Uncle, if you are wondering how to soften my shield and make it good for eating, just please put me to soak in the river.” The lion obliged, and the turtle immediately swam away to hide in the mud.

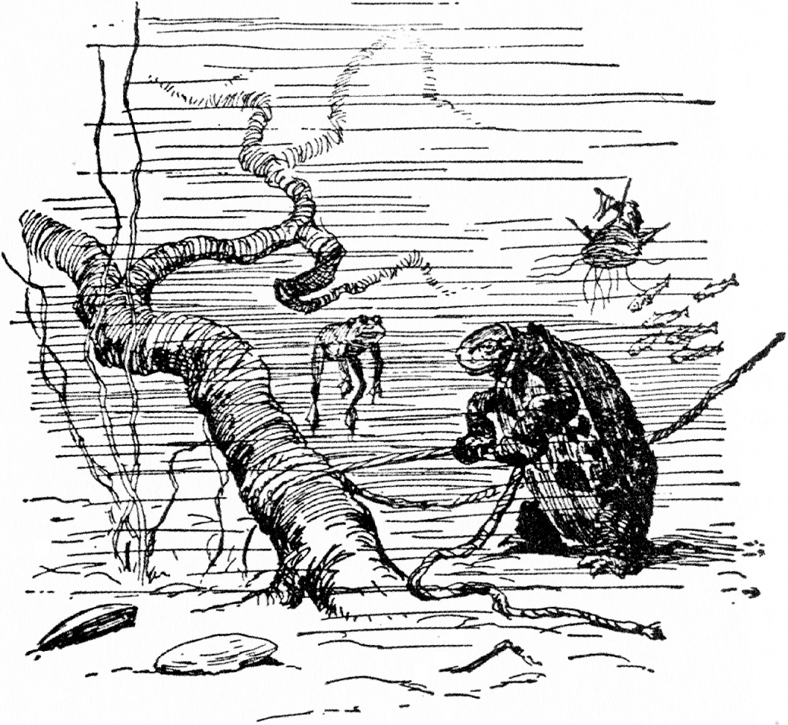

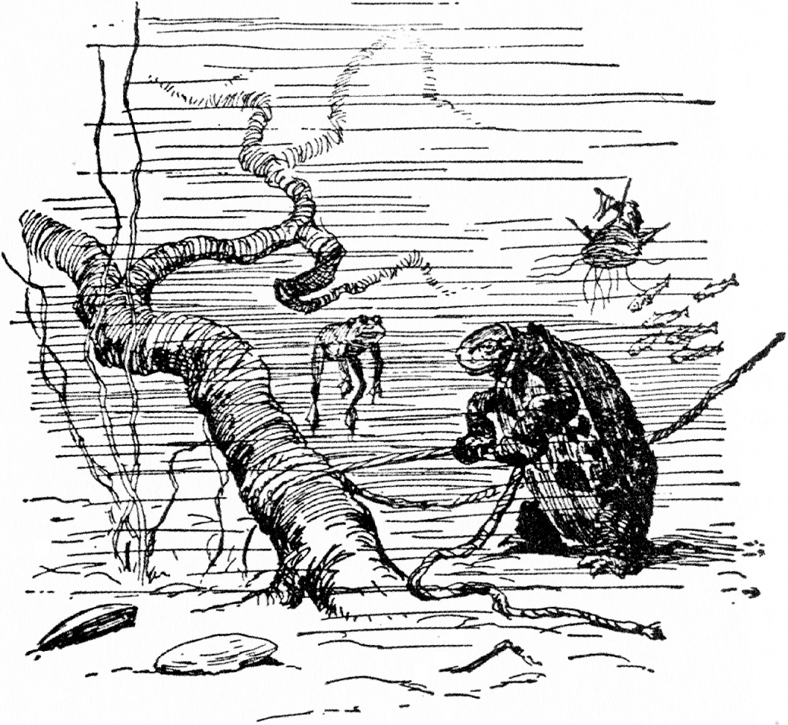

Brer Terrapin is having a tug of war with Brer Bear, but the clever turtle ties his end of the rope to an underwater root in this Uncle Remus tale by Joel Chandler Harris.

(Illustration by A. B. Frost)

This turtle deity was carried from Africa to the New World with the slave trade. When the slaves had to keep their practices and beliefs secret from their masters, they could draw inspiration from the silence of the turtle, as the humorous tale of “The Talking Turtle,” recorded in many variants from Africa and the Caribbean to the United States, illustrates. One version from Alabama began as a slave was walking along one morning and saw a turtle by the edge of a pond. “Good morning, turtle,” he said, being full of good spirits. “Good morning …” replied the turtle. As soon as he could recover enough composure, the man stammered that turtles cannot really talk.” “You talk too much,” said the turtle, and with that the creature slid into the pond. The slave ran home, and then returned with his master, to find the turtle once again in the sunlight on the edge of the pond. “Good morning, turtle,” said the slave. The turtle did not reply. “Good morning,” repeated the slave, a bit more insistently, but there was still no answer. “Liar!” shouted the master, and he beat the slave terribly. Later the slave returned to the pond and, finding the turtle in his accustomed place, began to reproach it for not having returned his greeting. The turtle responded, “Well, that’s what I say about you Negroes; you talk too much anyhow.”

In Uncle Remus, the collection of African-American folktales by Joel Chandler Harris, Turtle, or “Brer Terrapin,” is the cleverest of the animals, able to consistently outwit even Brer Rabbit himself. Brer Terrapin lacks the cruelty of the other beasts, and its presence softens note of the nihilism in the stories. One tale began as the animals were at a picnic, and, while the females prepared the food, the male animals began to boast. Brer Rabbit said he was the swiftest, while Brer Bear claimed to be the strongest, and so on. Brer Terrapin listened calmly until all were finished, reminded the company of how the tortoise had won a race against the hare in a famous fable of Aesop, and then challenged Brer Bear to a test of strength. Brer Bear took one end of a rope, while Brer Terrapin took the other and slid into the pond. Brer Bear tried to pull Brer Terrapin out of the water, but the rope would not budge. Brer Terrapin had tricked his adversary by tying the rope to a root. When the pulling finally stopped, Brer Terrapin undid the knot and slid out of the water in triumph. The turtle has become a beloved figure in books for children, from Lewis Carroll to Walt Kelly and Dr. Seuss.

he seashore has long been a place of wonder, where one can still find colorful stones, shells, bits of coral, smooth fragments of glass, and the relics of all sorts of strange and wonderful events beneath the waves. A few creatures such as turtles and seals are almost (though not quite) equally at home in two realms, earth and water; others, such as gulls, add the third realm of air. Often, the seashore symbolizes the intersection of time and eternity. In folklore, it is the abode of shape-shifters such as seals and swans, which cast off their skins to become human, and may then marry men or women.

he seashore has long been a place of wonder, where one can still find colorful stones, shells, bits of coral, smooth fragments of glass, and the relics of all sorts of strange and wonderful events beneath the waves. A few creatures such as turtles and seals are almost (though not quite) equally at home in two realms, earth and water; others, such as gulls, add the third realm of air. Often, the seashore symbolizes the intersection of time and eternity. In folklore, it is the abode of shape-shifters such as seals and swans, which cast off their skins to become human, and may then marry men or women.