HE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS DEPICTED THE SOUL OR BA, AS A SMALL body with wings. This is usually taken as a bird, perhaps an owl, but in some pictures it seems less a small avian than a large insect. The Greeks and Romans pictured the soul as a butterfly or moth. The Christian gospels tell of the resurrection of the body, and make no mention of a soul. That disembodied self is originally a pagan concept, which entered Christianity through the work of Plato and other Greek and Roman philosophers. For alchemists of the Early Modern Period, the soul was a “homunculus,” a diminutive human figure. Descartes believed that this little man was located in the pineal gland, right in the center of the human head, and gazed out through the eyes. Whatever its metaphysical status, we can understand the “soul” as a relatively ethereal aspect of a person or animal. The animals that can, at least at moments, represent the soul are small, and generally have a fluttering, spectral sort of flight or motion.

HE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS DEPICTED THE SOUL OR BA, AS A SMALL body with wings. This is usually taken as a bird, perhaps an owl, but in some pictures it seems less a small avian than a large insect. The Greeks and Romans pictured the soul as a butterfly or moth. The Christian gospels tell of the resurrection of the body, and make no mention of a soul. That disembodied self is originally a pagan concept, which entered Christianity through the work of Plato and other Greek and Roman philosophers. For alchemists of the Early Modern Period, the soul was a “homunculus,” a diminutive human figure. Descartes believed that this little man was located in the pineal gland, right in the center of the human head, and gazed out through the eyes. Whatever its metaphysical status, we can understand the “soul” as a relatively ethereal aspect of a person or animal. The animals that can, at least at moments, represent the soul are small, and generally have a fluttering, spectral sort of flight or motion.

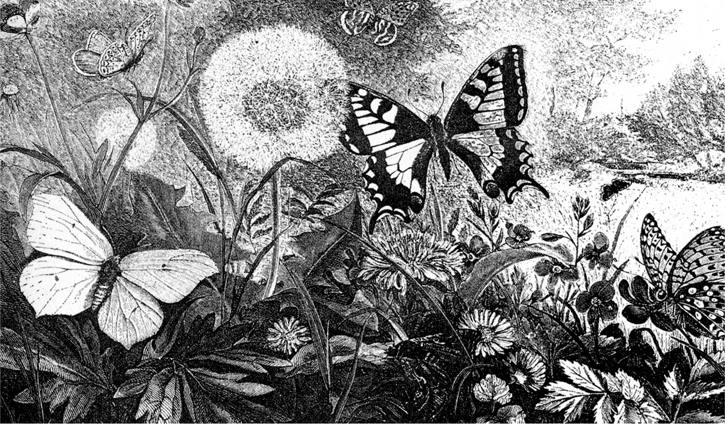

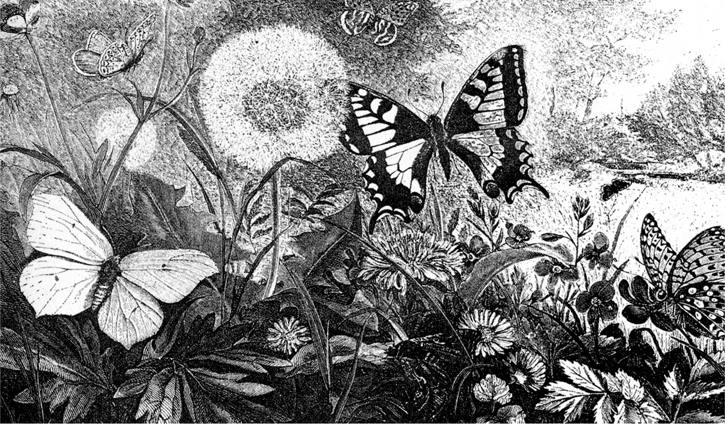

BUTTERFLY AND MOTH

I did not know then whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly dreaming I am a man.

—CHUANG TZU

The idea of a butterfly or moth as the soul is a remarkable example of the universality of animal symbolism, since it is found in traditional cultures of every continent. The custom of scattering flowers at funerals is very ancient, and these attract butterflies, which appear to have emerged from a corpse. A butterfly or moth will hover for a time in one place or fly in a fleeting, hesitant manner, suggesting a soul that is reluctant to move on to the next world.

The transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly provides the ultimate model for our ideas of death, burial, and resurrection. This imagery is still implicit in Christianity when people speak of being “born again.” The chrysalis of a butterfly may have even inspired the splendor of many coffins from antiquity. Many cocoons are very finely woven, some with threads that are golden or silver in color.

The Greek word psyche means soul, but it can also designate a butterfly or moth. The Latin word anima has the same dual meaning. Several carved gemstones from ancient Greece depicted a butterfly hovering over a human skull. Late Roman artifacts often depicted Prometheus making humankind while Minerva stood nearby holding aloft a butterfly, representing the soul. A story inserted in the first-century novel The Golden Ass by the Roman-Egyptian author Lucius Apuleius tells of a young girl named Psyche who was given to Cupid, the god of love, in marriage, and contemporary illustrations often showed Psyche with the butterfly wings. Western painters have at times depicted the soul as a small human figure with such wings, an image also used to represent fairies.

In lands around the Eastern shores of the Pacific Ocean, the idea that the soul of a person will return in the form of a butterfly and hover around the grave of the body is widespread. In Indonesia and Burma, people have traditionally considered that a butterfly entering your house is likely to be the spirit of a deceased relative or a friend. On the island of Java, it is traditionally believed that, during sleep, the soul may fly out of the body in the form of a butterfly; you should never kill a butterfly, since a sleeping person might then die as well.

The Chinese sage Chaung-Tzu—a disciple of Lao-Tzu, the founder of Taoism—claimed that he fluttered about as a butterfly at night. On waking, he would continue to feel the motion of wings in his shoulders, and he was unsure of whether he was truly a butterfly or a man. Lao-Tzu explained to him that, “Formerly you were a white butterfly which … should have been immortalized, but one day you stole some peaches and flowers … The guardian of the garden slew you, and that is how you came to be reincarnated.”

Their close association with flowers helps to make butterflies a symbol of both fecundity and transience.

The way certain butterflies perform a courting dance—each partner moving off in various directions yet always coming back to the other—has made these insects symbols of conjugal love, especially in Japan. Lafacadio Hearn collected a Japanese story of an old man named Takahama, who was nearing death. A nephew was sitting at his bedside, when a white butterfly flew in. It hovered for a while and perched near his head, when his nephew tried to brush it away. The butterfly danced around strangely, and then flew down the corridor. Surmising that this was not an ordinary insect, the nephew followed until the butterfly reached a gravestone and disappeared. Approaching to examine the grave, he found the name “Akiko.” On returning, he found Takahama dead. When the boy told his mother, she was not in the least surprised. Akiko, she explained, was a young girl that Takahama had planned to marry, but she had died of consumption at the age of eighteen. For the rest of his life, Takahama had remained faithful to her memory and visited her grave every day. The nephew then realized that the soul of Akiko had come in the form of a butterfly to accompany the spirit of his uncle to the next world.

The soul of a beloved also takes the form of an insect, probably a butterfly, in the ancient Irish saga of “The Wooing of Étaín.” The god Mider fell in love with a mortal named Étaín, but the goddess Fuamnach, his first wife, struck the young woman with a rowan wand and transformed her into a puddle. As the water dried, it became a worm, which then changed into a “scarlet fly.” “Its eyes shone like precious stones in the dark, and its color and fragrance was enough to sate hunger and quench thirst in any man; moreover, a sprinkling of the drops it shed from its wings could cure every sickness …” The insect accompanied Mider as he traveled and watched over him as he slept, until Fuamnach sent a fierce gale to blow it away. After being pursued constantly by the goddess for centuries, the insect was finally carried by wind into the goblet of a chieftain’s wife, who swallowed it with her drink, and then gave birth to Étaín, giving her, once again, the form of a girl. Mider searched for her for a thousand years, but, when he finally found her, Étaín had become the wife of Echu, the king of Ireland. Echu refused to relinquish Étaín, but Mider defeated Echu in a board game, winning the privilege of embracing Étaín in the center of the King’s hall. As they put their arms around one another, the lovers turned into swans, and flew away through the skylight.

As the pace of modern life has become increasingly frantic, people have come to admire the leisurely flight of the butterfly. As W. B. Yeats put it in his poem “Tom O’Roughley”:

‘Though logic-choppers rule the town,

And every man and maid and boy

Has marked a distant object down,

An aimless joy is a pure joy,’

Or so did Tom O’Roughley say

That saw the surges running by,

‘And wisdom is a butterfly,

And not a gloomy bird of prey.

The way a butterfly moves from flower to flower has also been decried as lack of commitment, and Yeats, in the same poem, calls it “zig-zag wantonness.” Today many ecologists regard butterflies as a keystone species, and they will count butterflies per acre in an attempt to determine the health of an ecosystem, perhaps in a manner not altogether different from that of diviners in the ancient world.

The distinction between butterflies and moths is not fully recognized by scientists, but, in folk culture, it is very simple—moths are nocturnal while butterflies are diurnal. Furthermore, butterflies have many dazzlingly bright patterns of color, while moths are usually shades of white and brown. When homes were lighted by candles or lanterns at night, people were particularly fascinated by those moths which would fly toward the fire, even when that meant they would expire in a sudden blaze. This image was often used by Sufi mystics to describe an ecstatic union with God. In one of his most famous poems, “Blissful Longing” (Selige Sehnsucht), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used this motif as a symbol of the desire of the soul for transcendence. It tells of a moth drawn to a flame and ends with these words:

And till you have stood this test:

“Die, and come to birth!”

You remain a sorry guest

On this gloomy earth.

While many find the poem beautiful, some critics have been troubled by its romantic celebration of death.

James Thurber satirizes this longing for oblivion, countering it with a little romanticism of his own, in his fable “The Moth and the Star.” A young moth conceived the idea of flying to a star, but his father said that was crazy, advising his son to focus on street lights, like any sensible young moth, instead. Ignoring parental advice, the moth kept trying to reach the star, and, though unsuccessful, lived out a full and contented life, while his moth, father, brothers, and sisters were all burned to death. The moral: “Who flies afar from the sphere of our sorrow is here today and here tomorrow.”

A compassionate view of a moth’s apotheosis in flame was expressed by the early twentieth century British author Virginia Woolf in her essay “The Moth.” She told of watching a moth dance about by day as its motions became gradually fainter. Many times she gave the moth up for dead, only to see it flutter once again. Finally, when the tiny body relaxed and then grew stiff, she felt awed by both the power of death and the courageous resistance of the spirit against so formidable an antagonist.

ENGLISH ROBIN AND WREN

Call for the robin redbreast and the wren,

Since o’er shady groves they hover,

And with leaves and flowers do cover

The friendless bodies of unburied men.

—JOHN WEBSTER, The White Devil

The connection between the English robin and the wren in folklore is so close that they have often been mistaken for the male and female of a single species. In Britain people say, “The robin and wren are God’s cock and hen.” The wren, which is grayish russet-brown, is associated with Christmas, while the robin, which is more brightly colored, is associated with Easter. According to a French legend, the wren fetched fire from Heaven, singeing its wings, and then passed the brand to the robin, which burned its breast.

In Lark Rise to Candleford, her account of growing up in rural England during the nineteenth century, Flora Thompson tells how boys would regularly take eggs from the nests of birds for food, decoration, and sport. The wren and robin, together with only a very few other birds, were spared because, to quote a saying:

The robins and the wrens

Be God Almighty’s friends.

But the wren has been viewed with more ambivalence than its little cousin.

The wren is known throughout Europe as the “king of birds.” In Latin, it is known as “regulus,” in Greek as “basiliskos,” and in Old German as “kunigli,” all of which mean “monarch.” The Roman author Suetonius claimed, in his history of the deified Julius Caesar, that the assassination of the dictator was foretold by the fate of a wren. Shortly before the dictator was killed, a wren, pursued by raptors and bearing a sprig of laurel, flew into the Hall of Pompey, named after Caesar’s former rival, where it was overtaken and torn to pieces. But, if the wren is a monarch, it is one without finery, courtiers, or weapons. It rules the animals in something like the way the soul may be said to govern the body.

The status of the wren as king may seem paradoxical, since people usually associate greatness with size. As might be expected, veneration of the wren generally appealed to common people rather than to elites, which is probably why the cult has been far more prominent in folklore than in literary culture. Nevertheless, archeologist Edmund Gordon believed that the wren was celebrated in an animal proverb, from the early second millennium, from Sumer, the oldest urban culture. When the elephant boasted about his size, another animal, possibly the wren, answered him by saying, “But I, in my own small way, was created just as you …”

The wren seems to proclaim this uniqueness with a remarkably loud, melodious song, which will usually capture the attention of a person strolling through a meadow long before the bird itself is seen. The best-known version of the story explaining how the wren became king of birds is by the Brothers Grimm. The birds gathered to select a king and decided that the crown would be awarded to whichever could fly the highest. The eagle flew far above all the other birds and descended to claim his prize. The wren suddenly piped up that the crown was his. He had lain unnoticed on the back of the eagle until the large bird began to descend, whereupon the wren took off and flew so high that he could see God himself. Other birds objected that the contest had been won through trickery and so the result was invalid. The assembly decided that the crown could go to whoever burrowed most deeply in the earth. While other birds such as the rooster and duck began to dig, the wren simply found a mouse hole and descended. Though birds continued to object, the wren, to this day, slips in and out of hedges and proclaims, “I am king.”

The story shows both the reverence and the ambivalence with which people have traditionally regarded the wren. In much of Europe, especially the British Isles, the wren is never killed throughout most of the year but is ceremoniously hunted on Saint Stephen’s Day, December 26. The body of the slain wren is paraded through the streets on a pole in a colorful procession, to the accompaniment of music and song. Many legends are invoked to explain the ceremony. One held that the call of a wren betrayed Saint Stephen to his persecutors. According to an Irish legend, the Gaelic warriors were once planning a surprise attack on the troops of Oliver Cromwell, but wrens alerted the enemy by beating on drums.

Still another legend, this one from the Isle of Man, relates that there once lived a mermaid whose beautiful form and sweet song were irresistible to men. She would gradually lure them into ever-deeper waters until they finally drowned. Finally, a knight came along who was able to withstand her enchantment. He was about to kill the mermaid, but she escaped by taking the form of a wren. From that time on she was compelled to assume the form of a wren one day every year. People would kill the birds without mercy on that day, in hope of finally putting an end to the sorceress, and the feathers of the wrens were kept for one year as a charm against shipwreck. The fact that there are so many explanations for this ceremonial hunt suggests that it goes back very far, perhaps even to Neolithic times, and its original significance has been lost.

In western France, a similar ceremony was sometimes performed with the robin on Candlemas Day. The body of a robin was pierced with the branch of a hazel tree, which was then set aflame. The robin of folklore, as well as the wren, has been intimately connected with death and resurrection. Most of the legends about the robin center on the bright red color of its breast. According to one tale, the robin tried to pluck the thorns from the crown of Christ, whereupon blood fell on its breast. According to a legend from the Hebrides, the fire that warmed the Holy Family in the stable was about to go out, so the robin fanned the flames with its wings, thus burning its breast.

The mysterious English children’s rhyme “Who did kill Cock Robin?” which provides an archetype for later murder mysteries, begins:

Who did kill Cock Robin?

I, said the Sparrow,

with my bow and arrow,

I killed Cock Robin.

Who did see him die?

I, said the Fly,

with my little eye,

I saw him die.

Who did catch his blood?

I, said the Fish,

with my little dish,

I caught his blood.

It concludes:

All the birds of the air

Fell a-sighing and a-sobbing,

When they heard the bell toll

For poor Cock Robin.

Linguistic analysis suggests that the poem may, in some form, go back to the fourteenth century CE or earlier. The widespread mourning indicates that, in this case, the robin, rather than the wren, is probably the king of birds. The earliest known version of the poem goes back to the mid-eighteenth century, when it was used as an allegorical allusion to the intrigues surrounding the abdication of Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Britain.

The robin traditionally attended to the bodies of those who had been denied a proper funeral. In the anonymous British ballad “The Children in the Wood,” an abandoned boy and girl perished in a deep forest:

No burial these pretty babes

Of any man receives,

Till robin-red-breast painfully

Did cover them with leaves.

But, for all the associations with martyrdom and death, the robin, like the wren, was generally thought of with joy as a herald of the spring. In the children’s classic The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, a cheerful robin led the heroine to the door of a wall surrounding an abandoned garden that was filled with mystery and wonder. Perhaps no other animals have been as symbolically linked with the seasonal rhythms of traditional rural life as the wren and robin. Today their use, especially on greeting cards, is increasingly nostalgic.

SPARROW

The brawling of a sparrow in the eaves,

The brilliant moon and all the milky sky,

And all the famous harmony of leaves,

Had blotted out man’s image and his cry.

—W. B. YEATS, “The Sorrow of Love”

The diminutive size of sparrows has often made them objects of affection, but their raucous, noisy behavior has hurt their reputation. The Greek poetess Sappho wrote of sparrows drawing the chariot of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. The sparrow was, however, often a symbol of profane love, which was sometimes contrasted with the chaste passion of the dove. The Roman poet Catullus wrote a tender elegy beginning “Mourn ye Graces …” (Lugete, o Veneres …) to the pet sparrow of his mistress. The author described how the sparrow would “chirp to his mistress alone,” and celebrated the great love they had for one another, clearly identifying with the bird.

Christ told his apostles, “Can you not buy two sparrows for a penny? And yet not one falls to the ground without your father knowing” (Matthew 10:29). Bede used similar imagery during the early eighth century in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, in which a noble said to King Edwin, “The present life of man, o king, seems to me, in comparison of that time which is unknown to us, like the flight of a sparrow through the room wherein you sit at supper in winter …” He went on to compare the sparrow flying from the warm room into the wintry storm with the passage of a soul into eternity, and then to say that Christianity offered promise of certainty in that precarious journey. The way sparrows nest in almost any enclosed space including the corners of barns or porches, has also made them symbols of domesticity. Folk belief, especially in Britain, often holds that deceased ancestors may come back as sparrows.

But the sparrows of folklore can also be malignant. One European legend says that when Christ was hiding from his pursuers sparrows betrayed him by their chirping. A similar legend says that when Christ was on the Cross the swallows tried to prevent his enemies from inflicting further torments by saying, “He is dead,” but the sparrows replied, “He is alive.”

Their integration into the routines of everyday life made the sparrow a politically charged theme in the middle of the nineteenth century. Sparrows from England were imported and became naturalized in major cities of the Eastern United States. An intense debate known as “The Great English Sparrow War” raged for several decades as to whether these birds were harmful to American landscapes, which closely paralleled the current disputes about whether the United States should welcome immigrants. Their detractors used the same sort of rhetoric to describe the sparrows that had been used to attack foreigners, calling the birds loud, unclean, and promiscuous. Others found the little creatures a charming addition to urban landscapes. English sparrows have at last been fully accepted by Americans, though more recent additions to North America such as starlings—first released in 1890 in New York’s Central Park—are still resented.

HE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS DEPICTED THE SOUL OR BA, AS A SMALL body with wings. This is usually taken as a bird, perhaps an owl, but in some pictures it seems less a small avian than a large insect. The Greeks and Romans pictured the soul as a butterfly or moth. The Christian gospels tell of the resurrection of the body, and make no mention of a soul. That disembodied self is originally a pagan concept, which entered Christianity through the work of Plato and other Greek and Roman philosophers. For alchemists of the Early Modern Period, the soul was a “homunculus,” a diminutive human figure. Descartes believed that this little man was located in the pineal gland, right in the center of the human head, and gazed out through the eyes. Whatever its metaphysical status, we can understand the “soul” as a relatively ethereal aspect of a person or animal. The animals that can, at least at moments, represent the soul are small, and generally have a fluttering, spectral sort of flight or motion.

HE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS DEPICTED THE SOUL OR BA, AS A SMALL body with wings. This is usually taken as a bird, perhaps an owl, but in some pictures it seems less a small avian than a large insect. The Greeks and Romans pictured the soul as a butterfly or moth. The Christian gospels tell of the resurrection of the body, and make no mention of a soul. That disembodied self is originally a pagan concept, which entered Christianity through the work of Plato and other Greek and Roman philosophers. For alchemists of the Early Modern Period, the soul was a “homunculus,” a diminutive human figure. Descartes believed that this little man was located in the pineal gland, right in the center of the human head, and gazed out through the eyes. Whatever its metaphysical status, we can understand the “soul” as a relatively ethereal aspect of a person or animal. The animals that can, at least at moments, represent the soul are small, and generally have a fluttering, spectral sort of flight or motion.