HY DO PEOPLE LOVE HORROR MOVIES? CREATURES WITH HUGE fangs and gleaming eyes may frighten us physically, but they reassure us intellectually, since we know exactly what these features mean. The beings that seem most unsettling are those that elude our habitual classifications. Their appearance may alternately suggest deities or demons, enchanted humans or dumb beasts, reptiles or mammals, and friends or foes. In Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas looks at the example of the pangolin—an anteater which has scales like a fish, looks like a lizard, climbs trees like a monkey, and has warm blood. It is the center of a cult among the Lele, a tribe in Central Africa, whose members eat it only on ritualized occasions, in hope that the magic of the animal will pass to them. The animals in this section may be more familiar, but they remain just as uncanny and mysterious.

HY DO PEOPLE LOVE HORROR MOVIES? CREATURES WITH HUGE fangs and gleaming eyes may frighten us physically, but they reassure us intellectually, since we know exactly what these features mean. The beings that seem most unsettling are those that elude our habitual classifications. Their appearance may alternately suggest deities or demons, enchanted humans or dumb beasts, reptiles or mammals, and friends or foes. In Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas looks at the example of the pangolin—an anteater which has scales like a fish, looks like a lizard, climbs trees like a monkey, and has warm blood. It is the center of a cult among the Lele, a tribe in Central Africa, whose members eat it only on ritualized occasions, in hope that the magic of the animal will pass to them. The animals in this section may be more familiar, but they remain just as uncanny and mysterious.

BAT

But when he brushes up against the screen

We are afraid of what our eyes have seen

For something is amiss, or out of place

When mice with wings can wear a human face.

—THEODORE ROETHKE, “The Bat”

Bats have always provided a problem for those who like to divide things into neat, unequivocal categories. Not only are they nocturnal but they also seem, in other ways, to reverse what we often assume as the natural order. They sleep hanging upside down by their feet. They live in shelters such as caves or hollow trees, but they also take advantage of human structures. Like most small animals that are often drawn to human habitations, bats have often been identified in folk belief with the souls of the dead. In cultures that venerate ancestral spirits, that has often made them sacred or beloved. When spirits are expected to pass on rather than return, bats appear as demons or, at best, souls unable to find peace.

According to one popular fable, popularly attributed to Aesop, the birds and beasts were once preparing for war. The birds said to the bat, “Come with us,” but he replied, “I am a beast.” The beasts said to the bat, “Come with us,” but he replied, “I am a bird.” At the last moment, a peace was made, but, ever since, all creatures have shunned the bat. The earliest version of this story, by the Roman Phaedrus, contained no explicit moral, and perhaps he intended to suggest that bats prefer human civilization to nature. The learned folklorist Joseph Jacobs, however, appended the lesson, “He that is neither one thing nor the other has no friends.”

Today taxonomists place bats in a separate order of mammals, but both lay people and scientists have puzzled for centuries over whether bats were avians, flying mice, monkeys, or something altogether different. A revulsion against them, however, is far from universal, and their quizzical faces have often inspired affection. Glass windows had been first invented by the Romans about 400 BCE, but they remained a only a curiosity until well into the Christian era, and so most people had little choice but to share their homes with bats. According to Ovid, the daughters of Minyas had refused to join the revels in honor of Bacchus but stayed at home weaving and telling stories. In punishment, they were turned into bats, in which form they continue to avoid the woods and flock to houses. In a similar spirit, the Medieval bestiaries praised bats for the way they would hang together “like a cluster of grapes,” adding “And this they do from a sort of duty of affection, a kind which is difficult to find in man.” In Medieval times it was not uncommon for the entire household from the Lord and Lady to the serfs to sleep in the great hall of the manor, and little privacy was available. In such close quarters, they must have felt rather like bats in a cave.

In Africa, Swahili-speaking people have believed that after death the spirit of the departed hovers near his body as a bat. People in Uganda and Zimbabwe have traditionally believed that bats taking wing in the evening are departed spirits coming to visit the living. The people of Ghana, however, consider the flying fox, a large bat, a demon in league with witches and sorcerers.

Perhaps the most unequivocally favorable view of bats has been found in China, where the word for “bat” also means “joy.” In ancient times, the Chinese had already noticed the service that bats provided by eating insects, thus impeding the spread of malaria. Bats seemed to exemplify such Confucian virtues as filial piety, since they would live together in a single cave for generations. The Chinese believed that bats live for centuries, and Shou-Hsing, the god of long life, is still depicted with two bats.

Bats did not really come to be thought of as “spooky” in Europe until the end of the Middle Ages. Within a century or so afterwards, however, Europeans began to regard bats as familiars of witches and as a frequent disguise for the Devil. Borrowing from the iconography of Chinese art, though often giving it another meaning, Western artists began to depict dragons and demons with the wings of a bat.

The association of bats with vampires—that is, the living dead—only goes back to the latter half of the eighteenth century, when the zoologist Buffon examined newly discovered bats from South America. Because the variety sucked small quantities of blood from cattle, though rarely from human beings, he called them “vampires.” At about the same time, a fashion for gothic horror began to spread through Europe, and popular writers discovered it was piquant to identify vampires with bats.

It was only in the twentieth century that the new medium of movies really established the popular association between the two. In a wave of vampire movies starting in the 1920s, actors such as Bella Lugosi gave Dracula and other vampires the appearance of bats, in many instances the ability to change into bats as well. They would, for example, sport a long black cape (like the wings of a bat), large ears, and claws. While some vampires were purely evil, others were grandly tragic, and quite a few were not so different from ordinary human beings. In the 1950s, the popular comic-book character Batman assumed many of the paraphernalia of vampire bats, but he used these to fight crime rather than to capture souls.

But the mystery of bats has not been diminished by either fantasy or science. In the late twentieth century, the philosopher Thomas Nagel probed the nature of consciousness in a famous essay entitled “What is it like to be a bat?” He tried to imagine what it might be like to navigate by sonar and decided that the human mind was unequal to the task. His conclusion was that we must recognize realities that we can neither state clearly nor comprehend.

FROG AND TOAD

The old pond—

A frog jumps in,

Sound of water.

—BASHO (Translated by Robert Hass)

Frogs and toads are usually found around ponds or in moist areas that, in the context of myth, suggest the chaos out of which living things were created. In mythologies throughout the world, frogs are associated with the primeval waters out of which life arose. Among the Huron Indians and other Native Americans, the frog is often a bringer of rain. The aborigines of Queensland, Australia have a legend that a frog once swallowed all of the waters on the Earth. There was a great drought, and the animals decided they could only save themselves by making the frog laugh. He remained unmoved by their comic routines until the eel danced before him, awkwardly twisting and turning, at which the frog began to chortle hysterically, releasing the lakes and rivers.

When people observed their copulation, which often lasted several days, frogs seemed to embody fertility. The female frog will often lay tens of thousands of eggs every year. The Egyptian hieroglyphic sign for “one hundred thousand” was a tadpole. On hatching, the transformation of a tadpole to a frog, the major model for shape shifters in myth and legend, begins. Until the twentieth century, Europeans widely believed that frogs were generated spontaneously out of earth and water, and that frogs could survive for centuries in stone. Evolutionary theory partially confirms the intuition of early mythologists about the primal origin of frogs, since fossils of frogs have been found going back at least 37 million years.

The economy of ancient Egypt was centered about the Nile River, which teemed with frogs. The frog was particularly identified with Hekat, a deity of fertility and childbirth. When the waters of the Nile receded, innumerable frogs would be heard croaking in the mud, an event that may have influenced many myths. In one Egyptian creation myth, Heket and her ram-headed husband Khnum made both gods and human beings. According to another Egyptian creation myth, the original eight creatures were frogs and snakes that carried the cosmic egg.

The Hebrews, who reacted vehemently against Egyptian traditions, considered the frog unclean. The Bible tells us that when the Pharaoh refused to let the people of Israel leave Egypt, Yahweh sent Moses to him with this threat, which he later carried out:

… know that I will plague the whole of your country with frogs. The river will swarm with them; they will make their way into your palace, into your bedroom, onto your bed, into the houses of your courtiers and of your subjects, into your ovens, into your kneading bowls. The frogs will even climb all over you, over your courtiers, and over all your subjects (Exodus, 7:27-29).

Though most of Hebrew tradition regards these animals as repulsive, some rabbinical interpreters during the Diaspora have seen the frogs in Egypt as heroic defenders of the faith. Not only did frogs fight on the side of the Hebrews, but they even hopped into fires, where they were martyred by being burned alive.

Since frogs are generally seen after a deluge, it may be that the Biblical plague of frogs once referred to a storm. The scriptures of the Zoroastrians mention frogs as among the first creatures to emerge from dark waters as part of a plague created by the demonic Ahriman. The Book of Revelations reports that demons in the form of frogs will spring from the mouths of the Dragon, Beast, and False Prophet. In Early Modern Europe, there were many reports of frogs or toads emerging from the mouth of a woman, an event that might sometimes be understood as evidence of witchcraft and, at other times, simply as a noteworthy phenomenon. In Charles Perrault’s tale “The Fairies” (1697), a fairy’s blessing on a kind, industrious girl, made diamonds and roses fall from her mouth with every sentence; the same fairy’s curse on the young lady’s lazy sister made vipers and toads drop from her lips instead. The good girl then married a prince, while the bad girl was driven from home and died alone in the forest.

The croaking of frogs around a pond has often suggested an assembly, which is a frequent theme in fables attributed to Aesop. In one of the most famous, the frogs were thriving in their swamp but longed for a conventional government. They asked Zeus to give them a king, and he laughingly threw a down a log. After recovering from their awe at the splash, the frogs began to dance on the log. After a while, however, they decided the log was not a proper king and asked Zeus for another. The god, in irritation, sent down a stork, and the new monarch immediately began to gobble up the frogs.

The Classical Greek poem “The Battle of the Frogs and Mice” is a burlesque of the martial epic. It began as a mouse, fleeing a cat, took refuge in a pool. A frog offered to carry the mouse to safety but drowned him, setting off a war between frogs and mice, filled with reckless courage and bombastic rhetoric. Finally, the mice appeared on the point of victory, but Zeus, looking down with pity on the frogs, sent crabs to drive the mice back in confusion. For a long time, the poem was attributed to Homer himself, but most scholars now date it from the third century BCE. The story may have been a satire on the Peloponnesian War, in which the frogs represented Athens, the great sea power, and the mice represented Sparta, the dominant military force on land. The crabs, then, would have represented the city of Thebes, which finally broke the power of the victorious Spartans. No doubt somebody who had grown tired of the grandiloquent speeches that always accompany bloody rampages wrote “The War Between Frogs and Mice,” and it is not very hard to guess why he or she may have wished to remain anonymous.

In “The Frogs” by the Athenian dramatist Aristophanes, frogs provided a chorus by croaking in the River Styx, as the god Dionysius visited the underworld—”bre-ke-ke-kex, koax, koax!” Just as the chorus in Greek tragedy tended to provide the perspective of ordinary people as counterpoint to the grand dramas being enacted, the chorus of frogs was a reminder of limitations that not even the gods could escape.

In Greco-Roman culture, frogs often had a reputation for coarseness, due to their wide mouths and muscular bodies. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid told how Latona, exiled from Heaven by Juno, wandered with her children, the god Apollo and the goddess Diana, about the earth. She knelt down to drink water at a stream, but some country bumpkins tried to forbid her. When she pleaded with them, the rough fellows responded with threats and insults, and they muddied the water with their feet. At last, she cursed them, saying, “Live forever in the foul puddle!” and the ruffians turned into frogs. The story anticipated the frequent depiction of toads and frogs in Hell—a favorite motif of many artists of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Frogs and toads were used in innumerable medicines and magical formulas. The Renaissance zoologist Topsell reported a superstition that, if a man wished to know the secrets of a woman, he must first cut out the tongue of a living frog. After releasing the frog, the man had to write certain charms upon the tongue and lay it on the woman’s heart. Then he might begin to ask questions and would get nothing but the truth. This, however, was a bit much even for the normally credulous clergyman, who remarked, “Now if this magical foolery were true, we had more need of frogs than of Justices of the Peace.”

The popular distinction between frogs and toads is not fully recognized by professional biologists. Both groups of amphibians are members of the order anura, and they are almost interchangeable in myth and legend. The word “toad” is generally, though not always, used for creatures of the family bufonidae, which have short legs, rough skins, and spend much of their time on land, and they are especially associated with cultivated places such as gardens.

Toads were frequently mentioned in witch trials as familiars, as well as ingredients in witches’ brews. Hieronymus Bosch showed a damned woman copulating with a toad in his painting “The Seven Deadly Sins.” Many painters of the early modern period showed demons forcing the damned to eat toads in Hell. Others depicted anthropomorphic toads or frogs cooking and devouring human beings.

The number of superstitions connected with frogs and toads was virtually endless. At least since Pliny and Aelian, toads have been widely considered poisonous. In Shakespeare’s Richard III, the wicked king was called a “poisonous hunch-backed toad.” It has, however, also been popularly believed that toads had a precious stone inside their heads. This stone has been avidly sought by alchemists for its magical properties, especially for use in detecting or neutralizing poison. Up through most of the nineteenth century and even afterwards, many books of natural history reported that frogs could survive for many centuries encased in stone.

In China, toads were one of the five venomous animals, together with the scorpion, centipede, spider, and snake. A three-legged toad was often depicted on the moon, with one leg representing each of three lunar phases. According to legend, the hermit Liu Hai decontaminated a pool by luring out the toad with a string of gold coins. He killed the toad, thus punishing the sin of avarice. Nevertheless, Liu Hai has often been painted with Ch’an Chu sitting affectionately at his side as a sort of pet, and the toad with a coin in its mouth has become a symbol of good fortune.

Sometimes people have envied the ability of frogs and toads to find contentment in a humble pond. The eighteenth century CE Japanese philosopher Ando Shoeki, a relentless critic of human arrogance, wrote that the toad once prayed to walk upright like a person. This was granted to him, but then he found that, with his eyes focused only on heaven, he could no longer see where he was going. When he regretted his request, heaven returned him to his original state. He had, the toad explained, been like the sages such as Shakyamuni or Lao Tzu, for “Looking only to the heights, they failed to see the eight organs of their own senses …”

In the modern period, people often found the perceived homeliness of frogs and toads endearing. An old story of a witch with a frog as her demonic companion evolved in the oral tradition to become “The Frog King” (or “The Frog Prince”), the first in the famous collection of German fairy tales by the Grimm Brothers. It told of a talking frog that was disenchanted, revealed to be a prince and married to a lovely young girl. “Frog Went A-Courting” became one of the most popular of British and American folk-songs. It told of a wedding feast of a frog and his mouse-bride, together with all the animals invited as guests. In Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1907), Toad is a rich, arrogant character, who, after being chastised in many rollicking misadventures, reforms to become a proper Edwardian country squire. In The Call of the Toad, a novel written by the German Günter Grass as a sort of epitaph for the twentieth century, the primeval voice of a toad served much the same role as the chorus of frogs did for Aristophanes—an admonition against hubris.

Nineteenth-century illustration to a fable by La Fontaine, “The Frog Who Wanted to Be as Large as a Bull.”

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville, from Fables de la Fontaine, 1839

THE HYENA

I will neither yield to the song of the siren nor the voice of the hyena …

—GEORGE CHAPMAN, “Eastward Ho” (Act V, Scene I)

If Hyenas are “laughing,” what is the joke? Maybe it is our efforts to put everything into neat categories. As intermediate creatures somewhere between felines and canines, hyenas have always filled people with consternation. Legends also make their gender indeterminate, and these have some basis in observation. Reversing the pattern found in most mammals, the female hyenas tend to be a bit larger than the males. More remarkable is that the females have a bulge of skin that resembles a male sex organ. The Greco-Roman author Aelian claimed that the hyena changed its sex every year. According to Aelian, the hyena could also put a creature to sleep with a mere touch of its left paw. The shadow of a hyena cast against the full moon reduced dogs to silence, so they could be carried off without resistance. The hyena imitated the human voice in order to lure dogs and even men to their doom. In seventeenth-century England, Topsell reported a rumor that hyenas could be impregnated by the wind.

From Africa to Europe, the hyena has usually been considered treacherous, stupid, and cowardly. One possible reason is that hyenas occupy roughly the same habitats in Africa as lions, and they often live by scavenging. Lions are symbols of kingship, making hyenas seem like venial courtiers. According to Medieval European bestiaries, the hyena (sometimes called the “yena”) lived in tombs and devoured dead bodies. Bestiaries also reported that the hyena had a stone in its head, which, when taken out and placed under the tongue of a person, could enable a man or woman to see the future.

One rare legend makes the hyena not only gentle but also motherly. Saint Macarius of Alexandria lived as a hermit in the desert, where his skill in healing was known even to the animals. Once, a mother hyena came to him bearing her baby in her mouth. Saint Macarius picked up the infant, looked it over, and realized that it was stricken with blindness. He made the sign of a cross with one hand over the baby hyena’s eyes, at which it immediately went to its mother’s breast and began to suck. Later, the mother hyena brought Saint Macarius the skin of a sheep, freshly killed, in gratitude. Saint Macarius, troubled by the mother having killed the sheep, refused to accept the gift. The mother bent her head and entreated. Finally, the holy man agreed, but only if the mother would promise henceforth not to hurt the poor by taking their sheep but to take only meat that was already dead. When the mother assented, he took the sheepskin and slept upon it until his death.

In the twentieth century, other maligned animals such as wolves have been redeemed, but the reputation of the hyena has changed little. In the 1994 Disney film The Lion King, the evil lion that wishes to claim the throne aligns himself with the hyenas. The makers of the film wished to be ecologically sensitive and to avoid condemning any animal, so they usually made the hyena leaders more goofy than malign. Nevertheless, the hyenas advancing against the lions in step recalled the Nazis marching in Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda film The Triumph of the Will. Several naturalists, perhaps beginning with Saint Macarius, have pleaded with the public without success to redeem the reputation of the hyena.

MANTIS

A grey locust, heedless of danger, walks towards the mantis. The latter gives a convulsive shudder, and suddenly, in the most surprising way, strikes an attitude that fills the locust with terror, and is quite enough to startle anyone.

—HENRI FARBE, Farbe’s Book of Insects

The word “mantis” is Greek for “seer,” and the praying mantis indeed looks the part. With its green or brown color, diaphanous wings, and stick-like appendages, the mantis blends very easily into foliage, but its long front legs are constantly moving. When they are raised, the mantis appears to be making a gesture of supplication; when they are lowered, it suggests hands folded in prayer. The wings of a mantis resemble the flowing robes of a priest, but the most noticeable feature of the insect is its enormous eyes, to which ancient legends accord a power to curse.

Among the Ngarinyin, an aboriginal people of Northern Australia, the mantis is the symbol of the mother goddess Jillinya, and it is often painted on rocks and in caves. Parents warn their children not to harm mantises, for Jillinya might retaliate by bringing storms. Among the Kalahari Bushmen of Southern Africa, the mantis is also regarded as a creator deity, which controls the wind and rain. People of East Asia have been impressed by the aggressiveness of the praying mantis, which is willing to attack creatures several times its size. A traditional saying in Japan goes, “… like a mantis raising its arms to stop the wheel of a passing cart.”

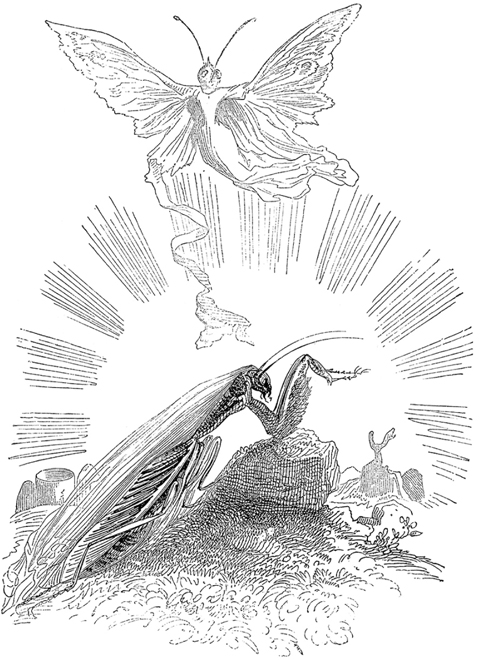

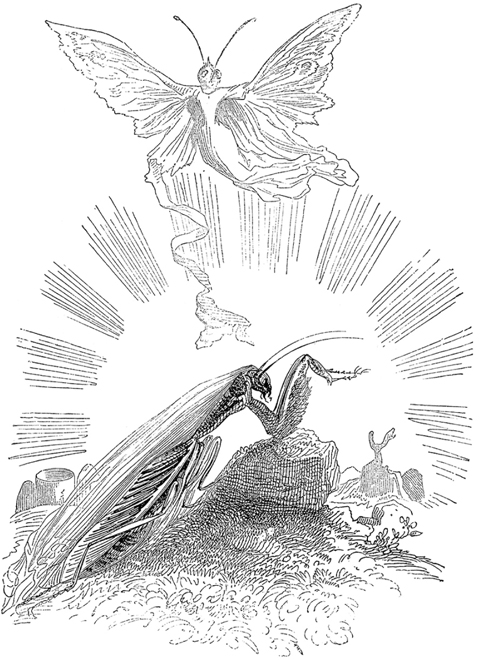

A praying mantis reborn into a better life.

(Illustration by J. J. Grandville, from Scènes de la vie privée et publique des animaux, 1842)

The mantis of folklore seems to veer between extremes of good and evil. There is a widespread legend that the praying mantis can divine the goal of a traveler at a glance, as well as any possible dangers along the way. In the mid-seventeenth century, Thomas Muffet (writing in collaboration with Edward Topsell) wrote of the mantis, “So divine is this creature esteemed, that if a child ask the way to such a place, she will stretch out one of her feet, and show him the right way, and seldom or never miss.” He added that mantises, “… do not sport themselves as others do, nor leap, nor play, but, walking softly, she retains her modesty, and shows forth a kind of mature gravity.”

In the nineteenth century, however, when females of the species were observed to eat their mates after copulation, people were disillusioned and began to demonize the mantis. The act could, however, also be interpreted romantically, by saying that the male mantis makes the ultimate sacrifice, in order to truly become one with his beloved.

Farbe remarks in this Book of Insects that the mantis “seemed like a priestess or nun,” but immediately added:

There was never a greater mistake! Those pious airs are a fraud; those arms raised in prayer are really the most horrible weapons, which slay whatever passes within reach. The mantis is fierce as a tigress, cruel as an ogress. She feeds only on living creatures.

He goes on to describe how the mantis can terrify even larger insects such as locusts. But it is hard to mistake a note of admiration for the mantis in Farbe’s description, not only for its martial prowess but also for courage and integrity.

Many philosophers, theologians, anthropologists and others have seen a kinship between the sacred and the profane. Deities from Ishtar to Yahweh have often been objects of love and terror, often of both at once, and no other animal exemplifies that union more than the mantis. In the words of Charbonneau-Lassay, the mantis is “the image of Christ, the guide of souls,” who may bring people to either Heaven or Hell.

HY DO PEOPLE LOVE HORROR MOVIES? CREATURES WITH HUGE fangs and gleaming eyes may frighten us physically, but they reassure us intellectually, since we know exactly what these features mean. The beings that seem most unsettling are those that elude our habitual classifications. Their appearance may alternately suggest deities or demons, enchanted humans or dumb beasts, reptiles or mammals, and friends or foes. In Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas looks at the example of the pangolin—an anteater which has scales like a fish, looks like a lizard, climbs trees like a monkey, and has warm blood. It is the center of a cult among the Lele, a tribe in Central Africa, whose members eat it only on ritualized occasions, in hope that the magic of the animal will pass to them. The animals in this section may be more familiar, but they remain just as uncanny and mysterious.

HY DO PEOPLE LOVE HORROR MOVIES? CREATURES WITH HUGE fangs and gleaming eyes may frighten us physically, but they reassure us intellectually, since we know exactly what these features mean. The beings that seem most unsettling are those that elude our habitual classifications. Their appearance may alternately suggest deities or demons, enchanted humans or dumb beasts, reptiles or mammals, and friends or foes. In Purity and Danger, anthropologist Mary Douglas looks at the example of the pangolin—an anteater which has scales like a fish, looks like a lizard, climbs trees like a monkey, and has warm blood. It is the center of a cult among the Lele, a tribe in Central Africa, whose members eat it only on ritualized occasions, in hope that the magic of the animal will pass to them. The animals in this section may be more familiar, but they remain just as uncanny and mysterious.