HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG OUR most ancient works of art. When human beings appear in these paintings, they are usually crude stick figures that the artists must not have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians also worshipped deities incarnated in bulls, crocodiles, cats, ibises, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. There is a bit of an archaic mother goddess in the “wicked witch” of Halloween with her faithful bat, spider, or black cat at her side. There has been a vast range of animals that, in particular cultures or historical epochs, have been considered divine, and this section looks only at a few that have most consistently been accorded that status.

HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG OUR most ancient works of art. When human beings appear in these paintings, they are usually crude stick figures that the artists must not have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians also worshipped deities incarnated in bulls, crocodiles, cats, ibises, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. There is a bit of an archaic mother goddess in the “wicked witch” of Halloween with her faithful bat, spider, or black cat at her side. There has been a vast range of animals that, in particular cultures or historical epochs, have been considered divine, and this section looks only at a few that have most consistently been accorded that status.

One of the many animals that could legitimately have been included in this chapter, which we have placed elsewhere, is the lion. It may be found in Chapter 6, “Tooth and Claw.”

DOVE

And the dove came to him in the evening; and, lo, in her mouth was an olive leaf pluckt off: so Noah knew that the waters were abated from off the earth.

—GENESIS 8:11

Doves seem holy and clean, but pigeons appear commonplace and dirty. Nevertheless, the two are very closely related in both biology and folklore. In ancient texts, it is often impossible to know which is meant, and perhaps the best way to think of these birds is as the sacred and profane aspects of a single creature.

A grove near the city of Dodona contained one of the most ancient and venerable oracles in Greece. In remote times, a black dove from Egypt alighted there. As it moved among the oak trees, the branches would rustle and speak to the priests with the voice of a woman. In the time of Homer, the shrine at Dodona was the most revered in all the land.

In the ancient world, doves were often associated with prophecy. In Apollonius of Rhodes’ The Voyages of the Argo, the Greek heroes in search of the Golden Fleece found their way through the sea barred by the Clashing Rocks, which would continually open and close. They released a dove, and because it passed between the rocks, the heroes knew they could navigate unscathed. In Virgil’s The Aeneid, doves guided Aeneas through a forest to a golden bough, which he needed in order to enter the world of the dead. Even Christianity, which often took a dim view of pagan oracles, was full of stories in which doves assisted in divination, perhaps because the doves seemed above every suspicion of evil. One apocryphal gospel told that a dove from heaven alighted on the staff of Joseph, anointing him as the husband of Mary.

Of course, whatever pleased the gods would be offered up to them in the ancient world. For the Hebrews, doves and pigeons were the only birds that might be offered for sacrifice (Leviticus 1:14), and they were the favorite sacrifice of people who could not afford sheep or oxen. The Biblical book of Genesis stated that, “God’s spirit hovered over the water.” This image certainly suggested a bird, and it has usually been depicted as a dove. During the Flood, Noah sent out a dove. When it returned with an olive branch, he knew that the waters had begun to subside. In Christianity, the dove represents the Holy Spirit. A dove descended on Jesus at his baptism. In pictures of the Annunciation, the dove has traditionally been portrayed descending to Mary from God the Father as she becomes pregnant with the infant Jesus. The scene recalls the amorous adventures of Zeus, for example for example when the god assumed the form of a swan to impregnate the maiden Leda. The dove, usually painted directly between Mary and God the Father, seemed to shield Mary with its purity.

The dove was sacred to many goddesses of the ancient world. Doves drew the chariot of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. Though sometimes thought promiscuous, Aphrodite became a guardian of chastity when the hunter Orion attempted to break into the home of the Pleiades, the seven daughters of Atlas and Pleione. She changed the girls into doves so they might escape by flight, and Zeus later transformed them into stars.

Doves fed the legendary Assyrian queen Semiramis, daughter of the goddess Derceto, when she was abandoned as an infant in the desert. They were also closely associated with the Roman Venus, the Babylonian Ishtar and the West-Semitic Astarte. This amorous symbolism enters the Judeo-Christian tradition through the Biblical “Song of Songs,” which probably referred to turtle doves:

The season of glad songs has come,

the cooing of the turtledove is heard.

The fig tree is forming its first figs

and the blossoming vines give out their fragrance,

Come then, my love,

my lovely one, come.

My dove, hiding in the clefts of the rock,

In the coverts of the cliff,

show me your face,

let me hear your voice … (2:12-14)

Jews and Christians have interpreted this song of love as an allegory of the longing of the soul for God. The image of the dove has always served to spiritualize erotic desire. It is also a symbol of conjugal fidelity. According to the Medieval German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach in his epic Parzifal, written in Germany around 12000, a dove that has lost her mate would always perch on a withered branch.

A Greek grave relief from the island of Paros, ca. 455–450 B.C. This girl is remembered caring for animals, perhaps at the annual festival of Artemis. She kisses one of two doves or pigeons which will go on to have a family though fate denied that privilege to her.

The Holy Spirit is traditionally spoken of with a masculine pronoun. Nevertheless, it is very hard to think of it as male. The Trinity and the very concept of God seem unbalanced without some feminine element. Several heretical groups have identified the dove with the feminine concept of sophia or divine wisdom, as well as with Mary herself. The winds of a dove spread out and pointing downwards are sometimes stylized in Christian art to form an “M” for “Mary.”

When Christianity was first introduced into Russia, people were forbidden to eat the flesh of doves. The dove is also important in the Grail Romances. In Parzifal, a dove visited the Castle of the Grail every year on Good Friday to bring the Host from heaven. The Dove was also the badge of the Knights of the Grail. European folklore made the dove the one shape that the devil could not assume. The dove was also one of the very few common animals that were never mentioned as a familiar of a witch.

In the ancient world, several cultures portrayed the soul as a dove. There is an enormously moving sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum from the grave of a Greek child who died in the mid-seventh century BCE. The young girl holds a pair of doves in her hands, and her lips touch the beak of one. The doves are to go on and have the marriage and family that were denied the maiden. The dove was the symbol of Saint Scholastica, founder of a convent and the patroness of rain. Her twin brother, Saint Benedict, visited her on her deathbed. When she died, Saint Benedict saw her soul ascend to heaven in the form of a white dove.

The dove is also holy in Islam. Christian polemicists sometimes tried to discredit Islam by claiming that Mohammed had a dove feed from his ear. This was allegedly a trick to make his followers believe that the Holy Spirit was giving him advice.

In their collection of German legends, the Grimm brothers tell how a dove saved the town of Höxter. This community had held out valiantly against the mighty army of the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years’ War. At last, when other attempts had failed, the imperial generals ordered their troops to bring the heavy artillery and bombard the town into submission. In the evening, a soldier was about to light the fuse of the first cannon, when a dove flew down and pecked his hand, forcing him to drop his kindling. The soldier took this as a sign from God, and he refused to fire. This delayed the bombardment long enough for Swedish troops to arrive and lift the siege.

The dove, particularly because of a drawing by Picasso, became a symbol of the peace movement during the Cold War. Is the dove a little too perfect? It suggests eroticism without lewdness and virtue without self-righteousness. It is rare indeed for any symbol to be accepted with so little ambivalence. Perhaps that is possible in this case because the pigeon functions as a sort of double to the dove, deflecting any resentment. Few people ever even think, at least consciously, of a connection between the dove on the street and the one in church, but isn’t that true of many religious symbols?

EAGLE

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in azure lands,

Ringed with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

—ALFRED LORD TENNYSON, “The Eagle”

The symbolism of no other animal is quite as simple and unambiguous as that of the eagle. It is associated with the sun and, largely by implication, with monarchs. Contrary to their reputation, eagles are not exceptionally high flyers among birds, but they are extremely powerful and often able to lift large prey such as sheep or monkeys. Perhaps their remoteness has also contributed to an exalted reputation, since they prefer rocky cliffs or tall trees for their nests. Though eagles may be majestic, we should remember that royalty have never been universally beloved.

This symbolism of the eagle was already clearly established in the ancient Mesopotamian poem of Etana, possibly the first ruler ever to have his story written down. It began as an eagle and serpent swore an oath of friendship to one another before Shamish, the god of the sun. The eagle lived in the top of a tree and the serpent at its base, and, for a time, they and their young would share every kill. One day the eagle ate the young of the serpent, who then burrowed in the carcass of a bull. As soon as the eagle approached to eat, the serpent bit him, cut his wings, and threw him in a pit to die of hunger and thirst. Shamish sent the hero Etana to rescue and nurse the eagle, who eventually became his guide. Etana mounted on the back of the eagle to fly up to the heavens, and ask Ishtar, a goddess of fertility, for the plant of birth so that he might have a son. The last sections of the manuscript are fragmentary, but Etana apparently did attain his goal and founded the first Sumerian dynasty.

The Greeks later retold the story of Etana, the serpent, and the eagle as an Aesopian fable of two quarreling animals—“The Eagle and the Fox.” The eagle violated its friendship with the fox by eating the fox’s cubs; the fox then set fire to the eagle’s tree in revenge. The story of Etana may well have influenced the Greek myth of Ganymede, a young man who was abducted by Zeus in the form of an eagle, so that he might serve on Olympus as cupbearer of the gods. Eagles, are, however, truly capable of carrying off an infant or small child, and perhaps the story goes back to such a tragic incident.

The eagle was sacred to the Greek Zeus. It was sent by the god of thunder to eat the liver of the disobedient titan Prometheus each day, who lay chained to a rock in the Caucus Mountains. The liver would grow back during the night; this continued until the eagle was finally slain by an arrow shot by Hercules. The Roman standard was an eagle, and people conquered by Rome also often adopted the symbol.

The eagle is the initial inspiration for a huge range of mythological figures. The double-headed eagle first appears on Hittite reliefs in Mesopotamia. From there it spread to the Byzantine Empire, to eventually become a symbol of both the Holy Roman Empire and Russia. The Assyro-Babylonian epic poem “Anzu” told of the lion-headed eagle, so powerful that it could cause whirlwinds simply by flapping its wings. It once stole the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil, the god of the sky, and briefly ruled the world. Mysterious figures, sometimes known as “demon-griffins,” were carved on palace walls of the Assyrian King Assyrnasirpal II. They had the bodies of men but the heads and wings of eagles, and they held up a pinecone in one hand, perhaps to enact a fertility rite

The lion shared a solar association with the eagle, and their features were often blended. Perhaps related to the lion-headed eagle, or imdugud, is the griffin, which has the face of an eagle, the body of a lion, and, sometimes at least, wings. The griffin first appeared in Mesopotamian art, but it quickly spread to Greece and beyond. Herodotus believed it lived in the mountains of India, where it made a nest of gold. Dante placed a griffin in Paradise, where it drew the chariot of the church.

Also closely related to the griffin was the Hindu Garuda, the King of Birds and the mount of Vishnu. He had the wings and beak of an eagle, and the rest of his body was human, but his vast form could darken the sky. Also inspired largely by the eagle were several other huge birds of legend such as the Arabian roc and the Persian simorgh.

In Christianity, the eagle became the symbol of Saint John the Evangelist, and is always depicted on the ground by his side. According The Golden Legend, written by Jacobus de Voragine in the late thirteenth century CE, this is because John once said, “… the eagle … flies higher than any other bird and looks straight into the sun, yet by its nature must come down again; and the human spirit, after it rests awhile from contemplation, is refreshed and return more ardently to heavenly thoughts.” But, like an eagle, John soars straight to the mystical heights at the start of his gospel: “In the beginning was the Word …”

Medieval bestiaries reported that, when an eagle grew old, it would first find a fountain. Then it would fly directly into the sun until its wings were singed and it fell into the waters. After repeating this three times, the eagle would be once again filled with youthful vigor, much like Christ who rose from the dead on the third day after his burial. It also resembled the legendary phoenix, which would immolate itself and be reborn from the ashes.

One of the very few literary works in which eagles are viewed not with awe but tenderness is “The Parliament of Fowles” by Geoffrey Chaucer, written in the late fourteenth century. On Saint Valentine’s Day, when the birds chose their mates, the birds gathered at the temple of Venus. Several birds paid court to the lovely female eagle that sat in the hand of the goddess. When they had all set forth their claims, Nature ruled that the female eagle herself should make the choice, thus upholding love over politics. Lords and princesses, after all, are still human beings, just as even eagles are birds.

In many ways, the Native American view of the eagle was surprisingly similar to that of Europeans. The Plains Indians, most especially, admired the strength of the eagle and associated it with the sun. The feathers of an eagle represented solar rays, and they were used on headdresses, shields, and dress to indicate skill in war or hunting. The Indians also stylized the eagle into a mythical creature—the thunderbird. The beating of its wings causes thunder, while its beak is like lightning. In Aztec religion, the golden eagle represents the sun god, Huitzilopochtli, and an eagle holding a serpent is depicted today on the Mexican coat of arms.

Depicted without the convention of heraldry, this eagle seems fiercer but more bestial.

(Illustration of bald eagle by John James Audubon, from Birds of America, c. 1828)

The eagle is a bit like a singer or actor who, after achieving great popular success, finds himself dominated by his own public image. People have trouble comprehending that the eagle, so mighty in legend, can be very vulnerable in reality. This creature has been so prominent in symbolism over the millennia that people even have trouble thinking of it as a genuine animal, and the cultural significance of the eagles seem to provide them with little protection. In countries such as the United States and Germany, eagles have become endangered despite being national emblems. Though legally protected, they are threatened by habitat loss and pesticides, though, due largely to strengthened environmental regulations, eagles are coming back in many regions.

RHINOCEROS

Ants and birds trace pattern in the dirt, but these creatures,

Armageddon in their shoulders, slip out of sight …

—HAROLD FARMER, “Rhinoceros”

Sometimes the legend and symbolism surrounding an animal becomes so elaborate that the creature itself is completely overshadowed, and such is the case with the rhinoceros. The creature is not one of the most important animals in myth or legend in any country. It has rarely been worshipped in temples or celebrated in epic poems. Nevertheless, sightings of the rhinoceros probably began and sustained the cult of the unicorn, which eventually also incorporated features of the horse, ass, goat, and narwhal. The irony is perhaps best illustrated in several Medieval treasuries of Europe, where the horn of a narwhal was kept as a relic of a unicorn. Alongside that horn was often that of a rhinoceros, which was believed to be a claw of a griffin. If we count the unicorn as a rhinoceros, the latter becomes one of the most important cult animals in the world.

The lore of the rhino/unicorn has a fascinating but very tangled history from the start, and there are possible depictions of it going back to prehistoric cave paintings. The first description, however, comes from the Greek Ctesias, who was the physician to the king of Persia around the start of the fourth century BCE. He considered the animal to be a giant wild ass, and nothing in nature matched his description. What suggests a rhinoceros, however, is his mention of the horn being used by Indians as a goblet as well as an antidote for poison. Rhinoceros horns have also been used for drinking, and folk medicine continues to attribute to them great potency as both a medicine and an aphrodisiac.

The description of a unicorn or “monoceros” by Pliny the Elder in the first century CE is more clearly suggestive of a rhinoceros:

… the wildest animal (in India) is the monoceros, whose body is like a horse but which has the head of a stag, elephant’s feet and a wild boar’s tail. It utters a deep, growling sound, and a black horn, two cubits long, protrudes from the center of its forehead. It is said that the animal cannot be captured alive.

Actual rhinoceroses had appeared in triumphal processions in Rome, and Pliny may have seen the animal but failed to connect it with the accounts from travelers.

From this point on, the lore of the unicorn became ever more elaborate and romantic in Europe, and its depiction became refined and delicate. Medieval people believed that the unicorn could never be subdued by force yet would lay its head in the lap of a virgin and allow itself to be captured. The rhinoceros, meanwhile, was usually known only from confused reports by travelers to exotic lands and, when mentioned at all, usually seemed diabolic by virtue of its brute power. When Marco Polo saw a Sumatran rhinoceros on his voyage to China, he was still able to connect it with the fabled unicorn. “All in all,” he wrote, “they are nasty creatures, they always carry their piglike heads to the ground, like to wallow in the mud, and are not in the least like the unicorns of which our stories speak in Europe. Can an animal of their race feel at ease in the lap of a virgin?”

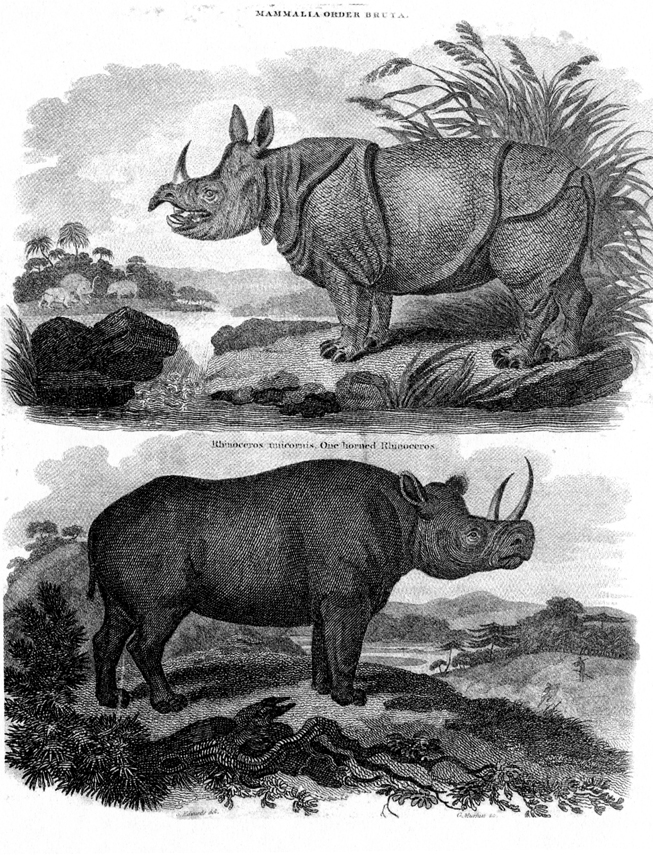

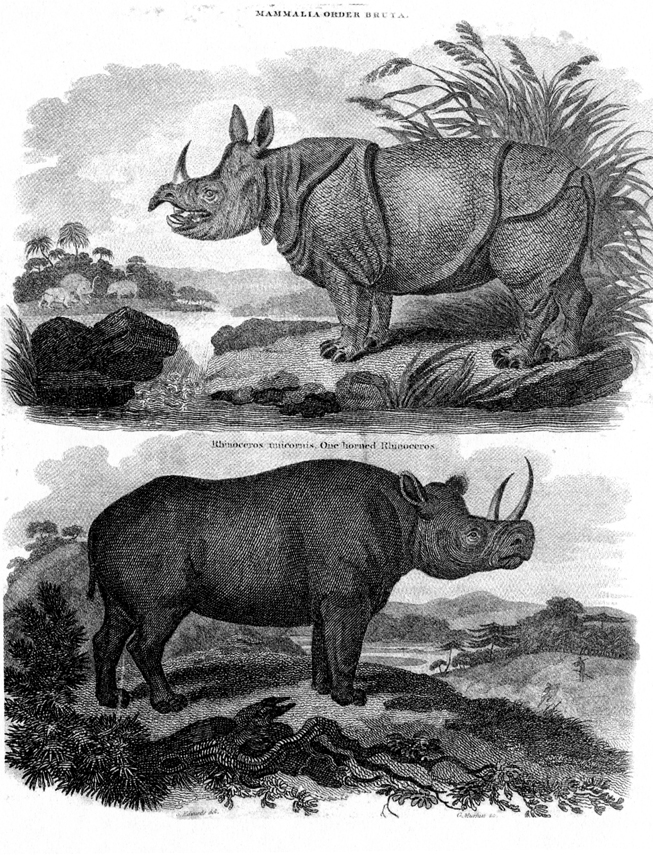

Illustrations of rhinos from a nineteenth-century book of natural history.

One feature of the unicorn, however, which observation did not seem to contradict was its reputation for near invincibility. In 1517, King Manuel I of Portugal brought a rhinoceros to Lisbon, the first one in Europe since Roman times. As an experiment, the King set the rhinoceros against an elephant on a street, and the pachyderm sought refuge by crashing through the iron bars of a large window. Not very long afterwards, Duke Alessandro de Medici had a rhinoceros engraved on his armor with the motto, “I make war to win.”

There are many other versions of the unicorn throughout Eurasia and beyond. The oldest may be the Ky-lin, which emerged from the Yellow River before the Emperor Fu Hsi around the start of the third millennium BCE. There is also the kirin or “Japanese unicorn,” which is known for its intense gaze and ability to divine whether an accused criminal is guilty or innocent. In those areas where the rhinoceros is known, it is usually at least vaguely associated with these legendary cousins.

Belief in the magical, medicinal, and aphrodisiac powers of the rhinoceros horn remains strong in the twenty-first century. Today, as many species of rhinoceros approach extinction, governments struggle with only limited success to prevent poachers from killing the animals for their horns, even though scientists affirm that these actually show no medicinal, aphrodisiac, or magical qualities. As is so often the case, research alone seems to command less credence than folkloric tradition.

HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG OUR most ancient works of art. When human beings appear in these paintings, they are usually crude stick figures that the artists must not have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians also worshipped deities incarnated in bulls, crocodiles, cats, ibises, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. There is a bit of an archaic mother goddess in the “wicked witch” of Halloween with her faithful bat, spider, or black cat at her side. There has been a vast range of animals that, in particular cultures or historical epochs, have been considered divine, and this section looks only at a few that have most consistently been accorded that status.

HE PREHISTORIC CAVE PAINTINGS OF FRANCE AND SPAIN ARE AMONG OUR most ancient works of art. When human beings appear in these paintings, they are usually crude stick figures that the artists must not have considered very important. The animals are painted with far more care and passion. The first clearly identifiable religious shrines in history are at Çatal Huyuk in Anatolia and date from around the middle of the seventh millennium BCE. They were dedicated to animals, especially bulls, but also vultures, foxes, and others. The Egyptians also worshipped deities incarnated in bulls, crocodiles, cats, ibises, and many other creatures. Over millennia, anthropomorphic goddesses and gods slowly replaced the animal deities. The archaic divinities accompanied their more human successors, often as mascots or alternate forms. Athena, for example, was pictured with an owl, Zeus with an eagle; Odin was accompanied by ravens and by wolves. The monkey Hanuman, who fought alongside the hero Rama in the epic Ramayana, is now perhaps the most popular figure in the Hindu pantheon. There is a bit of an archaic mother goddess in the “wicked witch” of Halloween with her faithful bat, spider, or black cat at her side. There has been a vast range of animals that, in particular cultures or historical epochs, have been considered divine, and this section looks only at a few that have most consistently been accorded that status.