CHAPTER 1

What Do You Want from Your Money?

Our Money, Ourselves

Once upon a time I would have said money is my currency, and then I might have said time is my currency. Now I’m at the point where I’ve realized it’s not time that’s my currency, it’s contentment.

Originally, I would sacrifice my contentment in order to go to school and then work all the hours after school that I could. Later on, I started realizing time is precious and [thinking about] what my time is worth. If I wanted to do something, I would think: Well, is it worth that much money?

Now, I’m in my early 30s so [when I look at how I spend my time] is it worth me working more to earn more money I might not need compared to doing the things that I enjoy but making less?

—Natasha, 30s, New Jersey, single, editor and publicist

What do you want from your money?

Have you ever asked yourself that specific question? If not, you’re far from alone. Most of the women interviewed for this book didn’t have the sort of quick answer you’d have when responding to a query you’d been asked loads of times, like: Aisle or window? Or, how do you like your steak? They took a minute, sometimes more, to really think about it.

And the answers, when they emerged, shared an important thread. One of the things we heard over and over was that money is not an end in and of itself. It’s not about amassing money—wealth—just to be rich. Instead, when we stop and take the time to think about it, we have clear, detailed answers about how we want to use it to build the lives that we envision for ourselves, our partners, our families, even the world.

But before we can get to those things, we have to conquer the four Ss.

LEVEL TWO

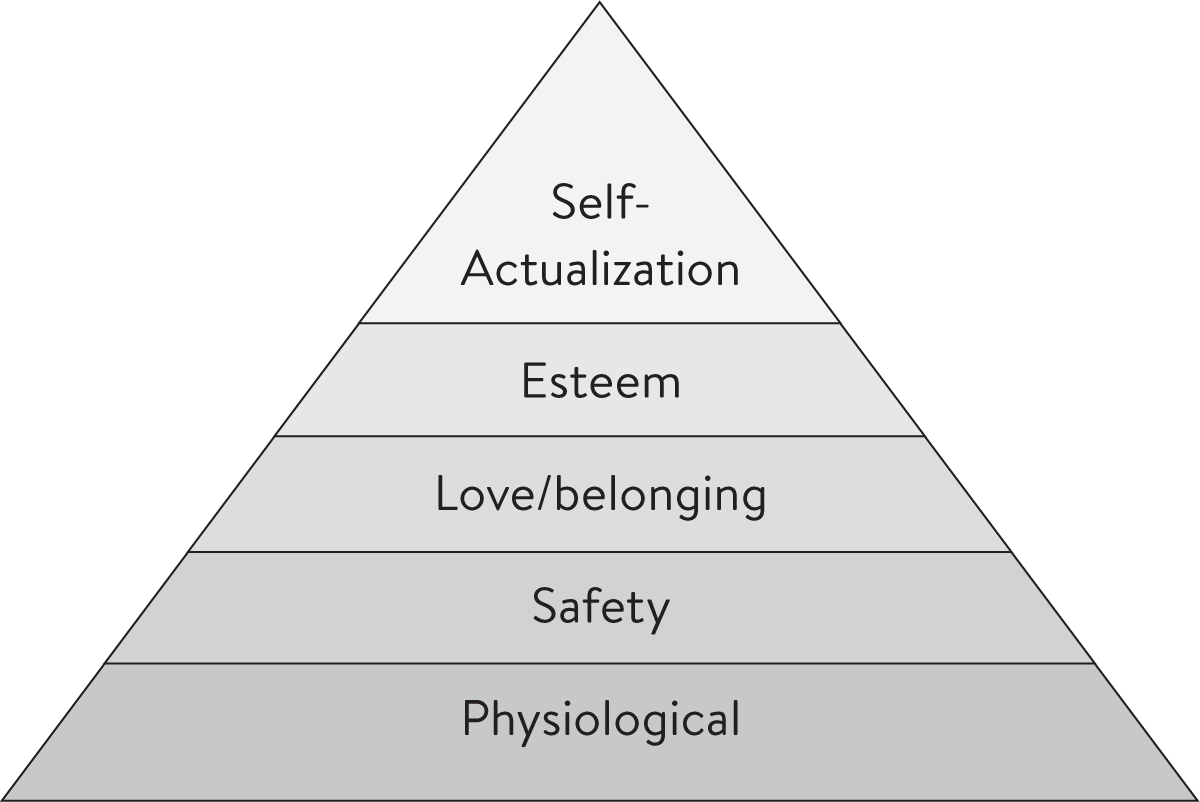

In 1943, a not-yet-famous psychologist named Abraham Maslow wrote a paper entitled “A Theory of Human Motivation” that was published in the journal Psychological Review. This was the world’s first look at his Hierarchy of Needs, which we’ve come over time to view as a pyramid. Essentially, Maslow argued that we have to satisfy the needs at the bottom of the pyramid—the ones that are tied to our survival, like food, water, and warmth—before moving to the upper levels, where we can focus on things like finding fulfilling relationships, doing work that makes us feel valued and accomplished, and achieving our full potential.

One after another, the women we interviewed told us that what they wanted most from their money is found on Level Two. Safety. Shelter. Security. Stability.

We want that feeling of knowing that we have landed somewhere that is solid and that no other person has the ability to remove the rock from under our feet. And many of us feel we have to lock that basic need down before we can allow ourselves to want pretty much anything else from our money.

That makes sense. If you’re in an environment where you feel secure and safe, comfortable and unthreatened, you’re more likely to be able to move forward in your relationships, career, and overall life. If you’re stressed because you fear an unpleasant surprise around the corner, not so much.

And when compared to men, we feel more insecure, more unsafe on a daily basis. This is not new. A few years ago, the Gallup Organization looked at how safe people feel walking alone at night in their own neighborhoods in 143 developed countries. Then they compared the answers of women to men. In 84 countries there were double-digit gender gaps—and high-income and upper-middle-income countries (like the United States) had some of the largest. In other words, if you’re living in a nice neighborhood, with a security system (or good dead bolts), your trusty pooch by your side and still feel frightened, it is neither a) irrational nor b) unusual.

What was interesting was the ways in which this Level Two quest manifested itself. For some, like Tracey, 30s, a lawyer in New York, it means a house, plain and simple. “We purchased our house before I got pregnant,” she says. “I wanted that stability.” Ariel, a 36-year-old antiques store owner from New Jersey, concurs. “Success is my home and what my home represents,” she says. “Money is the tool to get there.”

I can totally relate. When I got separated and then divorced, about a dozen years ago, I was laser focused on buying a house—and making it a place my kids would be comfortable and I could curl up and decompress when they were with their dad. I wanted cozy, with nooks to read and watch TV. I wanted warmth. Never mind that real estate prices were so high that even if I sold today, I wouldn’t get what I paid. (I went to contract in May 2005. The bubble popped the next year.) Renting would have made considerably more sense, and yet I wouldn’t even think about it. It had to be mine so that no one could take it away from me. In fact, when I remarried a few years later, I refused to let my new husband buy in. For me, it was enough to buy the house. For other women, the need runs deeper. They want to own it outright. Christine, 30s, a business coach from Kentucky, says one of her “big goals” is to pay off her mortgage, noting, “I think there’s something psychological about having that.”

SAFETY GIRLS

The desire for safety popped up in other ways as well (making me think of when Julia Roberts presented a panoply of condoms to Richard Gere in Pretty Woman, telling him matter-of-factly, “I’m a safety girl”).

We heard a lot about safe cars. “My husband feels like there’s [a set of expectations] that this is where the successful people in our community live, this is the kind of car they drive. He gets caught up in that,” says Lisa, 50s, who runs a health and wellness business in Wisconsin. “I’m more concerned about safety features as I’m carting my kids around.” Riki, 40s, from Arizona, agrees. “My feeling is that it’s okay that I’m not driving a Ferrari, but I need at least a very safe car and a car that’s reasonably new,” she says, “which is why I lease all the time.” (Again, just for the record, I’m on the same page as both. I drive a Volvo—wait for it—station wagon.)

But there is also a large cadre of women for whom safety is even more, well, literal.

SAFETY = SAVINGS

The Merriam-Webster dictionary, editions of which have been published since 1828 (who knew!) has a veritable laundry list of meanings for the word save when used as a verb. Among them:

• To deliver from sin

• To rescue or deliver from danger or harm

• To preserve or guard from injury, destruction, or loss

• To put aside as a store or reserve

Forgetting the first (it was at the very top of their list, so I had to include it), for many women the safety and security that can come from money is best found in actual savings. As in money. In. The. Bank. Kathleen, 40s, a single mom from New York, explains:

It’s a huge feeling of safety for me to have money saved. In fact, I sold my apartment in Brooklyn before I adopted my son and ended up in the suburbs, and now I rent. And what I like about that is I feel strongly about hanging on to my money. I know it’s [not as smart as investing it would be] but I feel pretty uneasy at this point about money, and one thing that makes me feel a little bit better is seeing a balance in various—so called—safe places right now.

Heather, 50s, a literary agent in New York, has experienced a similar desire to hoard cash at points in her life where she was about to take on more risk in her career. “The first time I quit a big job, I needed some $800,000 in the bank from a home sale to feel confident enough to take that leap.” Interestingly, as she became more certain of her ability to keep earning, the amount she needed in the cash stash lessened significantly. The second time she quit a big-paying job, she had an $80,000 cushion—and when she eventually quit corporate life entirely to launch her own firm, a tenth of that. “I think once you learn that you can catch yourself when you’re leaping and flying, that net doesn’t need to be so large,” she says. “Instead, you realize you are the net.”

BEYOND SAVINGS: FREEDOM

Once we’ve achieved a certain level of safety, or satisfied any other more primal needs, then what is it we want from our money?

Actually, that’s the wrong question. There are as many answers to what is it we want from our money as there are colors on the Pantone wheel. The right question is what do you want from your money, which is another way of asking what do you want from your life.

Going through the process of figuring this out—which we are going to do together in a moment—is likely to require a pencil and some paper. You’ll want a quiet space. It’s not a one-and-done kind of thing, but rather something you’ll start, put down, go back to, and pick up again. And it will, as many women noted, change as you age and change yourself. That’s to be expected and perfectly fine. You’ll revisit and tweak and forge ahead.

The point is that for all but the very, very wealthiest people on the planet, money is a limited resource. We will be happiest about how we use our resources if we can line them up with the things that line up most closely with our values. Things, importantly, can be both tangible and intangible. Tangible ones—like the houses or the safe cars or the clothes that make us feel confident and polished, or the Labrador retriever who makes every day better by greeting us at the door—are easy to get a grip on because we can envision them. Intangibles are harder to express because they’re more difficult to see—but they tend to come out in words like freedom, flexibility, and time. For example:

• Freedom to leave a bad relationship. Having money gave me the peace of mind to know that being unhappy in a marriage didn’t mean I needed to stay in it because I didn’t have financial security. That was a big thing for me. I’m really lucky because I know there are women who couldn’t do what I did. (Zoe, 40s, divorced, nonprofit director, New York)

• Freedom to leave work you don’t love. I worked, pretty much all my life, and never really loved it. So the fact that I don’t have to work anymore and I can do whatever I want is great. (Carol, 60s, married, retired, North Carolina)

• Freedom to give back. I’d love to spend the second half of my life volunteering. We’re on the right track now, but we’ve still got a ways to go. (Jenn, 30s, married, commercial banker, Tennessee)

• Freedom from financial risk. When I have enough money that I don’t have to risk it in the market any longer and I’m able to live off that… I’ll know I’ve achieved financial security. (Gina, 30s, married, CEO, Michigan)

• Freedom from asking permission. [I’d like] to be able to do what I, myself, want to do… have a roof over my head, pay my bills, drive to work, communicate with my family, spend quality time with my friends… without having to be concerned about [anybody else]. If I think it’s reasonable to do what I want to do with the money, I want to be able to do it. (Natasha, 30s, single, editor and publicist, New Jersey)

• Freedom to stop thinking about money at all. Real success for me would be to not care about money anymore—to feel that we have enough of it that I don’t need to worry about it. But the more money I make, the more I think that’s not really an attainable goal. (Kristin, 30s, engaged, social media manager, Vermont)

THE INTANGIBLE WILD CARD: TIME

There’s one other big variable in this equation: time. More specifically, your time.

It was a man, sadly, who first said that “time is money.” I had hoped it was one of those brilliant queens that Judi Dench plays in the movies. It was Benjamin Franklin. And the full passage reads like this:

Remember that Time is Money. He that can earn Ten Shillings a Day by his Labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that Day, tho’ he spends but Sixpence during his Diversion or Idleness, ought not to reckon That the only Expence; he has really spent or rather thrown away Five Shillings besides.

Franklin had the math right, but the sentiment wrong—particularly for our chockablock days. Our challenge is figuring out not just when time is money, but when money can be time. When does it make sense to use our money to free up our time for endeavors that are more meaningful or valuable than working? When can money be used to remove some of the stress associated with doing a particularly difficult or unwelcome task ourselves? Think about small things like ordering in when you just don’t want to cook, hiring a car to take you to the airport because parking is a nightmare, getting a blowout because… well, just because.

Then, think of the bigger ones. Money can buy you the time to spend with a friend you haven’t seen in forever (or one you see all the time but can’t get enough of). It can buy you time to spend with a parent who’s not doing well, time to work an hour less each day so you can explore a new pastime, to stay home part- or full-time with a child. It bought Christin, 30s, a new mom in Washington State, a year at home with her newborn son. “I know that I am very fortunate and many people don’t get this luxury,” she says. “But I am grateful for every day I have with him.”

The goal is to think about it almost analytically—to figure out at what points in your life applying the money-to-time-conversion math makes sense for you as Gina, the 30-something CEO from Michigan, explains:

I run my own company. So the more I work, typically the more I will earn. [Sometimes,] I will overwork to make sure I’m saving at a higher rate so I don’t have that additional stress and concern. [Other times, I make the decision to trade] business time for personal time. I certainly do everything within my control not to spend those extra evenings at the office that I could be home with my family. And last year before my oldest daughter went off to college, I made the professional decision to take every Friday off that summer to spend as much quality time as I could with all three of my girls together while they were all still at home.

WANTS VS. NEEDS FOR GROWN-UPS

So, let’s figure it out. What do you want your money to do for you?

When we’re teaching financial literacy to children, one of the first issues is to get them to separate needs from wants. A warm coat? Need. A jersey with the logo of your favorite team? Want. Lunch? Need. Lunch at the new sushi place on the corner? Want.

They get it almost immediately. But then they grow up and it turns out we’ve been feeding them a bunch of baloney (sometimes literally). Behavioral economist Sarah Newcomb explains that the strict dividing line approach has several problems. First, there are needs and then there is a whole array of approaches to meeting that need. You need transportation. Does that mean you need a car? A luxury car? Perhaps not, when transportation could be a bus. A bike. Uber.

The second—and perhaps bigger issue for women—is that when we tell ourselves that anything not essential to our basic survival is unnecessary, we’re ignoring a whole, vast category of needs: our emotional ones.

For Newcomb herself, beauty is a need. “It is incredibly important in my life,” she says. “I feel comforted by it. I get a lot of enjoyment from beauty. And so, for me, beautiful clothing and having a home that is beautiful are really deep needs.” Your emotional needs may be different. Comfort. Luxury. Excitement. The key is accepting that a) they are needs, b) they are not irrational, and c) you’re going to be unhappy if you don’t find ways to meet them. Then you can go about doing exactly that with the resources you have. They don’t have to be all that pricey, either. Newcomb has learned that a bubble bath enjoyed while sipping a nice glass of scotch and listening to some “slow jams” can bring on a feeling of beauty and luxury that is deeply satisfying and personal to her.

That’s important. Because the third issue is that trying to ignore your needs simply doesn’t work. You know this if you’ve ever been hangry. You go through your day without stopping to eat, and for a while it doesn’t matter. Then your stomach starts sending signals to your brain that it’s waiting. Send a little something my way, it asks you. Doesn’t have to be much, a yogurt maybe, or a Kind bar. But you’re on a roll and you ignore it. And a little while later, you’re over the precipice, so cranky you’re going to eat the last eight Mallomars—dammit. Never mind the fact that you know your kids will want one before bed. Never mind knowing that no one ever wants to think about the fact that they just downed eight Mallomars. Our emotional needs are just like the feelings of being hangry. They get louder and more insistent if we try to ignore them.

And the fourth, and final, issue is that we are surrounded by needs that are not our own, but that others—friends, relatives, advertisers—want us to embrace as our own. These are the shoulds. Anytime you catch yourself thinking of doing something or buying something because it is expected of you or because you’re trying to keep up—with trends or with other people—you are likely in should territory. Shoulds should be avoided at all times.

SYNCING OUR VALUES WITH OUR SPENDING

It doesn’t matter if we’re talking about a little bit of money or a lot; if we can get to the point where we are lining up our values with our spending, we are going to feel better about how we are using our resources. We are going to feel as if we’re getting more value from our money.

Here are two exercises to help you do this. The first looks backward. The second looks ahead.

Suggestion 1: Give up the ghost (of guilt).

I’m Jewish, so believe me when I say I get guilt. I not only get it, I suffer from it and have a hard time escaping it—even when I try. But try we should. Guilt takes a toll on our productivity, creativity, efficiency, and concentration. It makes it difficult to enjoy whatever it is we’re doing. And guilty feelings, according to psychologist Guy Winch, take up about five hours per week.

What exactly is guilt? In the legal sense, it involves having committed a crime. In the emotional one, it’s feeling you’ve failed to do something you were supposed to do. A lot of guilt comes from our inner voices—including the feeling that we’re doing better in our lives (or the world) than we deserve. But other people can lay on the guilt in order to get us to do things their way. As it relates to our money, that can mean using our resources (or time) to do things they want us to do—buy things, contribute to their charities, attend to their priorities—rather than things we want to do.

From within or without, it’s crucial to recognize that whether we actually give in to that guilt is a choice. We can choose to not buy in—to decide that our feelings of how we should use our time and our resources are in fact more valid than those of anyone else. If you are a chronic sufferer, that’s easier said than done. So how do you eliminate it? On my podcast, Ettus offered one method that has been working for me. “The thing to realize is that when you’re feeling guilty, literally no one is winning, and someone—and I would argue more than one person—is losing,” she said. “You’re losing because it affects your stress and your health, and that, of course, impacts your kids and your partner and your friends and anyone around you.” Her solution is to try to be more present everywhere you are.

It works. “If you’re giving 110 percent at the office, it’s much easier to go home and shut that off. If you’re with your kids at night and you’re turning off the phone and spending two hours literally listening to them, engaging with them, it’s worth more than eight hours of distracted parenting,” Ettus explains. I concur. Being there with the kids, or your partner, is also the antidote to spending money you don’t particularly want to spend to compensate for the fact that you’re not around.

Suggestion 2: Cop to your own excuses.

As I mentioned in the introduction, I wrote a whole book about these a decade ago. Make Money, Not Excuses detailed how the stories we tell ourselves get in the way of plowing ahead and taking hold of our financial lives. The book lined up and then knocked down the most common money excuses at the time.

• I don’t know where to begin…

• I’m not good with math (numbers)…

• I’m too disorganized to deal with my money…

• I don’t have any time…

• But my husband does that…

• I have nothing to wear…

In order to fight your own excuses, you have to first recognize that you’re making them. So, start listening to yourself. And then pick one excuse that you want to focus on at a time and approach it like you’d approach any other goal. Break it into manageable pieces. Take one step at a time. Once you’ve taken each step, allow yourself to recognize and feel good about the fact that you’ve made progress. Then move on to the next.

If you’re telling yourself you don’t have time for money, try freeing up fifteen minutes every day to do something financial: Read the business section of the paper. Start organizing your accounts so they make sense. Start researching financial advisors.

Suggestion 3: Accept that you deserve it.

Another thing that may be standing in your way is your own inability to be giving to yourself. In order to get what you want from your money, you have to accept that you deserve this money—in other words, give yourself permission to have it and enjoy it.

There have been umpteen studies about why women still earn just (about) four-fifths of a dollar for every dollar a man earns. This is true even when you look at a playing field that should ostensibly be level. A 2016 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine looked at the salaries of male and female doctors. It methodically compared apples to apples—looking at docs with the same specialties, years of experience, localities—and still found women earning an average of $20,000 less a year. When asked why, the study’s lead author told Time magazine that it’s because women a) don’t negotiate and b) don’t go out and get offers from other employers so that they can go back to their current one with evidence that they should be paid more.

Why don’t we? In part, it’s because we understand (and again research backs this up) that advocating aggressively for ourselves at work comes at a high social cost. In the eyes of other people, our likability goes down. (Just ask Hillary Clinton. When she was advocating for the country as secretary of state, her polling numbers were through the roof. When she was advocating for herself as candidate for president, not so much.)

But we may also not be sure that we deserve it—that we’re worth it. Jennifer, 30s, a health insurance executive with a young child, was living in California when she and her husband decided they wanted to move back home to New Jersey. Jennifer approached the CEO of her company about it and he said fine—but that he was taking $20,000 off her annual salary because of what her move would cost him. “I was grateful to keep my job and so I went along with it, even though I thought it was ridiculous,” she said. But once the move was under her belt, she took a look at her workload and realized just how much it had increased. And she went back to that CEO and pointed out that he had docked her twenty grand while giving her double the work. “It became a conversation,” she said.

Heather, the New York literary agent, had a similar experience a little over a decade ago. At the time, she was not an agent, but a book editor—a stellar one, mind you, who routinely had two or three books on the New York Times best-seller lists. Her two children were 1 and 5, and she wanted to work from home on Fridays. The female head of her department would only allow it with a four-day workweek and a 20 percent reduction in salary. Heather took the deal with the understanding that the four-day week was supposed to grant her a similar reduction in work. “Needless to say, that didn’t work,” she shares. “The resentment I felt at the cut when I was their top producer and trying to now shove what was always a seven-day workload into four to make up for it led me straight back to the five-day workweek at my former pay after a few months.”

Now, a decade and a half later, Heather says, she would have told them where they could stick their four-day week. “There’s no way I would undervalue myself in that way.”

The key to dealing with this, says business strategist Leisa Peterson, is learning to question your assumptions of what’s right, what’s allowed, and what’s outside of that. If something falls outside the lines and it’s standing in your way of living your life to the fullest, it’s time to go back and explore why. Why are you not allowing yourself to have these things—or do these things—even though, from a strictly financial purview, they are absolutely possible right now? And what would happen if you changed that?

Family

Family