That night, the Southland’s warm air blew out over the Pacific, cooling quickly as usual, then growing thick with condensation. The next day dawned gray and foggy, like many mornings in Los Angeles. By noon, however, the sun had burned off much of the haze. The sky sparkled, not blue so much as white, like a worn seashell wet from the waves.

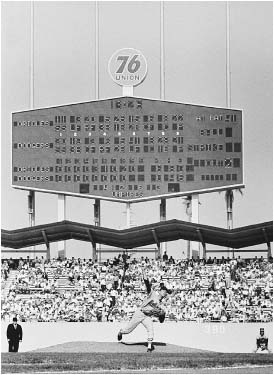

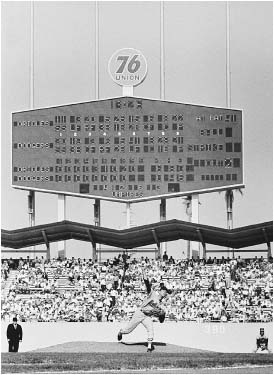

Before the game, Vin Scully discussed the ramifications of this with television viewers. “This might be one of the toughest ballparks in the big leagues to play the outfield in,” he observed. “Most baseball parks are two decks, the lower and upper stands. Here you have six. It is extremely difficult to get a good jump on a ball when you are looking into six decks of color, on a bright day such as this.” Scully then reminded everyone about Yankee first baseman Joe Pepitone, who, in the fourth and deciding game of the 1963 World Series, had been unable to pick up the throw from Clete Boyer at third because of all the white shirts in the Dodger Stadium crowd. Pepitone’s error had cost New York the game.

At field level, settling into seats behind cages in the stadium’s exclusive dugout boxes, were some of the biggest names in entertainment—Louis Armstrong, Doris Day, Milton Berle, Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant—all freshly coiffed, splendidly attired, and happy to cheer the hometown boys. But after the teams were introduced, the anthem sung, and the Dodgers took the field, it wasn’t one of these famous pretty people who threw out the first ball of the game. That honor went instead to a shriveled and stooped man with a face permanently leathered by thousands of innings of baseball. At age twenty-two, this man had started in center field for the Dodgers. Fifty-four years later, in 1966, Casey Stengel had at last taken himself out of the game long enough to be elected to the Hall of Fame.

Living now a few miles away from Dodger Stadium, just over the hill in Glendale, Casey had been attending Dodger home games throughout the season, marveling at Wes Parker’s glove work, Jim Lefebvre’s range, Maury Wills’s intensity, and, in particular, the greatness of today’s starting pitcher, Sandy Koufax. 1 In his playing days, Stengel had faced most of baseball’s pitching greats—Christy Mathewson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson. He felt that Koufax was better than any of them. “It takes almost a miracle to beat him,” Casey pointed out. “You try to put the whammy on him. But when he’s pitching, the whammy tends to go on vacation.”

A journalist waylaid Sandy before the game to find out whether he could fathom Casey’s trippingly surreal “Stengelese.” “When I was young and smart, I couldn’t understand him,” Koufax acknowledged. “But now that I’m older and dumber, he makes sense to me.” 2

At one P.M., the television cameras focused on Stengel as he rose ceremonially before his seat. He shifted the baseball to his left hand and, to much applause, fired it out of the stands into the waiting mitt of John Roseboro. Casey’s craggy face, visible worldwide on tens of millions of television sets, creased into a smile. “He had a little something on that one!” laughed Vin Scully. “The great Charles Dillon Stengel!”

Casey couldn’t have been happier. One of the first telegrams to reach Alston in the Philadelphia locker room the previous Sunday had been from Stengel, congratulating him on “expertly” managing the Dodgers. Anticipating this World Series, Casey felt no divided loyalties, even though he had managed most of Baltimore’s coaching staff when, in more youthful days, they had played for the Yankees. “I’m a National League man,” he firmly declared. But he gave the Orioles plenty of credit. Securing this year’s world championship would not be easy for Los Angeles. “We all know,” he allowed, “Frank Robinson is a tough man. They even know it now in Cincinnati.” And the flawless play of Brooks Robinson astonished him. “From Kansas City to Kankakee and back again, I ain’t never seen nothing like the guy on third. And then, when you see him, you don’t believe it.” 3

Vegas held LA at 8-to-5 favorites to win Game Two.

One individual who felt differently was Jim Palmer, the Orioles’ choice to start opposite Koufax. Palmer had been observing closely the previous afternoon when Drabo had closed down Los Angeles with his velocity. “You can beat the Dodgers with a fastball,” Palmer had assured the press afterward. It was a naively arrogant disparagement for an erratic, inexperienced pitcher to pronounce against the current champs, and it made all the papers. In the morning Palmer awoke to roughly the same dilemma that Joe Namath later found himself in, on the day of Super Bowl III, against Baltimore’s great 1969-1970 Colts. Like Namath, Palmer had to deliver an impossibly gutsy performance that could match his underdog braggartry. The scrawny, twenty-year-old right-hander, with the overdrawn eyebrows and red crabapples for cheeks, now had to go out and beat the greatest southpaw in baseball history.

Ultimately, Jim Palmer would be an Oriole for nineteen years. He would pitch nearly four thousand major-league innings, post a career 2.86 ERA, and become the first pitcher to win as many Cy Young Awards as Sandy Koufax. But all that was in the future, vague and unknowable. On October 6, 1966, he was merely a kid who couldn’t control his curveball, an orphan whose adoptive father had died, whose adoptive mother had remarried, whose family, though wealthy, kept moving, living on Madison Avenue in New York City, then in Beverly Hills, then in Scottsdale, Arizona. He was only seven years removed from the junior high schooler who had fallen asleep listening to Vin Scully recount Dodger games on KFI.

What made Palmer’s comment of supreme self-confidence all the more astonishing was that he was injured. Throughout the 1966 season, after games and on off days, he had spent much of his time painting his new ranch house. “I would come home and get a fresh roller and mix up a gallon of Sherwin Williams. Again and again. That roller, heavy with paint, down the wall. Heavier and heavier. Roll after roll.” This exercise was not, by any means, among those recommended for a pitcher, whose overtaxed arm was ideally limited to carefully monitored tosses between starts. “By the northeast wall of the second bedroom, my arm started to hurt a lot. I got introduced to cortisone injections.”

Thus, by Game Two of the World Series, Palmer already had a tight shoulder. He would later admit, “In the back of my mind I was wondering, ‘How’s my arm going to hold up?’”

Palmer started off strong, retiring the side in the first, three up, three down. Ron Fairly led off the second. Palmer walked him. In stepped Jim Lefebvre, the number-five batter. The switch-hitting Lefebvre, like Wills and Gilliam before him, turned around to bat from the left side against the right-handed Palmer. It didn’t matter; Palmer promptly struck him out. Next up was Lou Johnson.

Fairly, the least fleet Dodger, took a short lead at first. Without Scully at the helm, there was no chance that Fairly would be running. Nonetheless, Palmer checked him before throwing home. Sweet Lou swung weakly, slapping the ball off the end of his bat into right field. It was a single, the first Dodger hit of the day. As Robby ran up to catch it on the bounce, he lost his balance and fell down. Johnson rounded first and kept going; he made it into second standing up. The throw went home, holding Ron “Not-Be-Nimble” Fairly at third.

From the radios in the stands came the sound of broadcaster Bob Prince grousing. As in Game One, the “transistor tune-ins” had to make do with Chuck Thompson and Prince, “the Gunner,” as he was called. “A very typical Dodger rally in the making,” snorted Prince. “A base on balls and a bloop off the end of the bat. This is just a typical Dodger rally. They did it so many times over the season that… you know how they play for it.” (This was what kept my guys from rightfully taking the league, the ever-partisan Pittsburgh announcer seemed to be saying, this piddling style of ball.)

Runners on second and third. One out. The batter Roseboro.

Palmer ran a fastball in on the handle. Roseboro, jammed, popped up to short. Runners held. Two down.

Wes Parker stood in, with Koufax on deck. Shortstop Luis Aparicio hustled in to talk with Palmer. They elected to walk Parker (.253 on the season) to get to Koufax (.076 on the season). As the crowd jeered and catcalled, Etchebarren hopped to his left four times to catch enough pitchouts to put the slight, erudite first baseman aboard.

The bases were loaded for number 32, who could hit off others about as well as others could hit off him. (“I can think of only one advantage I have in pitching against Sandy Koufax,” Jim Palmer had informed reporters that morning. “Don Drysdale is a better hitter.”) 4 In his entire career, Koufax had but two regular season home runs. In seventeen World Series games, he’d recorded only one hit. His arthritic elbow had eroded his swing of late, reducing it to a one-handed punch of the bat. The first pitch looked good enough. Sandy took a tremendous undercut and hit a high fly into shallow right. Davey Johnson dropped back to catch it for the third out.

Three Dodgers were stranded. Bob Prince was astonished. “The Baltimore Orioles are out of a jam!” he exclaimed. (His error-prone Pirates would have been down by a couple of runs by now.)

Returning to the Oriole dugout, Frank Robinson was mad at himself for falling while fielding Johnson’s one-out blooper. “It’s a high sky,” Frank observed to young center fielder Paul Blair, “very bright. Tough to see the ball.”

“It’s brutal out there,” Boog Powell agreed, hoping he didn’t get any pop flies at first. 5

Blair nodded. The fall sky throughout California had a distinctive glare: the sun dropping toward the sea, the clear western sky gleaming with refracted light. Robinson had seen a lot of it growing up in Oakland. Blair, a former Angeleno, was familiar with it too. He also knew that this park was worse than most. 6 The screen in back of home plate gave off a funny gold glare that made it difficult to locate the ball.

Paulie stopped. He had to think about hitting. He was due to lead off the inning.

Blair was nervous. 7 He deposited his glove and hat on the Baltimore bench, donned a helmet, took up a bat, stepped out onto the grass. His family was in the stands. “Paulie!” they called, waving. Meanwhile, sixty-plus feet away, the hero of Blair’s teen years loosened up, throwing smoke. Koufax’s warm-up pitches smacked Roseboro’s glove with a characteristically wet pop, the splat of futility.

Paulie swung his bat in a circle of chalk. He knew well the fog that settled like a cough in the low San Gabriel Mountains, lingering even into early afternoon. It slowed fly balls, tugging at them slightly. This was why, among those great Dodger teams, only pitchers, never hitters, would find themselves inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. This was also primarily why the entire 1966 Dodger roster combined to hit only as many home runs as three Orioles (Robby, Brooks, and Boog).

When public-address announcer John Ramsey spoke Blair’s name and the plate umpire motioned for him to stand in, Paulie was so lost in thought he didn’t know where he was. He managed to locate the batter’s box, but Koufax quickly rang up two strikes on him. Blair connected on the next one, flying out, somewhat respectably, to Ron Fairly in right field. Relieved, Paulie dashed back to the dugout while Etchebarren, the number-eight hitter, came to the plate.

Koufax started Etch off with a curve. Etchebarren checked his swing. “Ball!” the umpire bellowed. Another curve. This one came in about six inches over Etch’s head, then fell like a wounded bird. Etch froze, his bat still cocked, watching as the pitch tumbled through the strike zone and Roseboro caught it on the ground. 8

“Strike one!”

The 1–1 pitch was a fastball down the middle. Etch swung, came up empty.

“Strike two!”

Another fastball down the middle.

“Strike three!”

Etch went and sat down.

Representing the lineup’s bottom was Jim Palmer. Koufax had retired the eight batters before him with supreme efficiency. Aparicio had outrun an infield grounder before being picked off first, then Blefary and Robby had popped out. Brooks had fouled out, then Boog, Johnson, and Blair had popped out. Now Etchebarren had struck out. In two-and-two-thirds innings, Koufax had thrown just twenty pitches. Eighteen had been strikes. What could Palmer possibly hope to achieve?

The Baltimore pitcher promptly popped the ball up. Gilliam moved in to catch it on the infield grass. Palmer did not put his head down as he ran. Instead, he held his chin up proudly, content with having gotten at least some wood off the great man.

Back in Baltimore, the sun had sunk behind the facades of the stone buildings. The smokestacks, church steeples, and row house chimneys seemed to stretch toward the last light, while the emptying factories receded into the shadows. By five o’clock, Kirson’s bar on Greenmount Avenue was packed. Not a stool was available, not even the one directly beneath the big color television set. 9

There was a homey, congenial feel in the crowded tavern. The late-afternoon sun coming through the front window lit up lazy clouds of cigarette smoke and played off the creased faces of Kirson’s stolid clientele—a steelworker, a mechanic, several factory workers, a retired sailor, a schoolteacher, a Bendix draftsman, a machine salesman, an operating room assistant. Many had been coming here since… well, since forever. Some of them even remembered the shoemaker’s shop that had been on the spot before Al Kirson had taken it over.

Amid them, a Baltimore Sun reporter leaned on the glass of the Laguna Beach pinball machine, drinking, jotting in a notebook. The tavern fans let no Oriole action go by without a vigorous response. They’d cheer when a Baltimore batter paused to knock the dirt from his spikes. “With only three scoreless innings behind us,” wrote the reporter, “the cast in the bar is like a light opera company about to break into song.” 10

To them, the game’s color broadcast on NBC looked positively radiant. Most Americans did not yet own a color television, and only a few shows were broadcast in the broader spectrum. In every sense, the country was used to seeing things in black and white.

No African Americans were present at Kirson’s because Baltimore’s bars had yet to be desegregated. The only blacks arrived there through the TV.

In the top of the fourth, with the game still tied at nothing apiece, Aparicio flied out to the infield. Blefary did the same. Sandy’s pitches continued to display great movement. He’d given up just one ground ball. The game was another gem in the making.

Frank Robinson approached the plate for the second time.

Once again the game’s top pitcher faced its best offensive player: the winner of pitching’s Triple Crown (ERA, victories, strikeouts) versus the winner of batting’s Triple Crown (average, RBIs, home runs).

There had been a time when Frank had handled this pitcher easily. “How do you hit Koufax?” Robby had once been asked. “Right-handed,” he’d replied, with a sideways grin. 11 Over half a dozen seasons, from 1956 through 1961, he’d hit well over .300 against Sandy. That had ended in 1962, when impatient umpires had begun calling more strikes, the Dodgers had moved to Chavez Ravine, and Koufax had shed his wildness. After that, although Sandy had become an iconic presence, the most popular ballplayer in the land, and the foremost southpaw in the game’s history, he’d never stopped feeling threatened by Frank’s devastating power. Thinking back on the challenge Robby represented whenever he stepped into the box, Koufax had winced. “Like any other outstanding hitter, one year he might hit .500 against you, another year hardly anything.” In fact, counting today, Frank had faced him forty-five times since 1962 and hit safely just four times. It was not, as the ever generous Koufax remembered of their matchups, “Sometimes yes, sometimes no.” 12 During those years, it was almost always no.

Baltimore’s scout Jim Russo had sat down with Robby and the other Orioles before the game to go over Koufax. “Bunt on him,” Russo had recommended. “Steal on him. Don’t swing at any high strikes or balls out of the high strike zone. Look for his big breaking curve to hang.” He had recommended that they lay off of Sandy’s high hummer, because of the bizarre way it seemed to rise. It would appear belt high and quite inviting as it approached, and then, at the last split second, the chagrined batter would find himself reaching for a pitch that floated around the bill of his batting helmet. By not swinging at these, Russo had said, they would force Sandy to pitch them low. The Oriole hitters had nodded at all this, then turned to Robby, who’d watched Koufax far more and from a far better angle than Russo, and asked his advice. “Go up there and bear down,” Frank had encouraged his teammates, “and if you get a strike off this guy, take your cuts.”

Frank had followed his own advice in Game Two, fouling off a couple in the first before flying out to Lou Johnson in left. In this at bat too, Frank wasn’t shy about swinging at whatever looked good. The count went to 3–1. He fouled off the next pitch.

As the ball sailed out of play, Robby had an epiphany: Koufax was losing his rhythm.

Frank would later pinpoint this at bat as the moment he knew that Baltimore would win the game. Having to pitch the pennant clincher with only two days’ rest was telling on Sandy. He’d gone 2–2 on Blefary; now the count was full on Frank. This wasn’t the same Koufax that Robby had faced as a member of the Cincinnati Reds.

Koufax missed high with a 3–2 curve, and Frank took first. It was Sandy’s first walk of the game, and he scuffled around the mound, disgusted with himself.

Brooks Robinson followed. He hit the 2–2 pitch on the ground toward the shortstop hole. Third baseman Gilliam cut across the diamond for the ball, but fumbled it for an error. Robby rounded second, saw nobody covering third, glanced at the infield, gathered the impression that the ball had gone through. 13 Impatient and eager to score, he took a couple of steps toward third. Gilliam came up with the ball, turned, and fired to Lefebvre at second. The crowd roared. Frank was trapped and tagged out.

Inning over.

Although his baserunning had been inadequate, Robby’s assessment of Koufax’s condition was accurate. In the fifth inning, Sandy threw four pitches before getting a single strike on Boog Powell. And then, with the count 3–1, Boog singled to shallow left for the Orioles’ second hit. Davey Johnson tried to sacrifice but popped the ball high in the air down the first-base line. It was foul. Both Roseboro and Parker pursued it. They nearly collided, but the catcher reached high with one hand to snatch the ball from the first baseman. “The best steal the Dodgers have made yet,” sportswriters scoffed.

The Baltimore rooters at Kirson’s were distracted. A drunk man had pushed open the door, staggered inside. He wore a painter’s outfit and an Oriole cap. The stub of a cigar was stuffed into his happy, screwed-up face. He shoved and gesticulated until he’d cleared some space for himself in the thick crowd. Al Kirson came around the bar, took the painter by the elbow, steered him outside onto the street. “Warm up and come back tomorrow,” Kirson shouted, then shut the door. He glanced at the chalk scoreboard beside the bar. 14 The game remained scoreless. One away in the fifth, with “Boog the Behemoth” aboard at first.

Paul Blair was up. As in the third inning, Koufax quickly had him in the hole. But down two strikes and no balls, Paulie launched a towering fly to deep center. Willie Davis drifted to his right, looked up. The sun blazed into his eyes from above the five-tier grandstand.

Both Alston and Blair would agree that when a ball got directly in the sun, nothing could help. Tommy Davis, Ron Fairly, and Maury Wills would point out how much farther south the sun was at this time of year, which made it even tougher on the center fielder, and it was always especially harsh at this hour.

Something bad was due to occur. The vivid memory of Minnesota’s Frank Quilici dropping an infield throw last year, Scully’s prescient invocation of Joe Pepitone, Alston’s remarks the day before about the difficulty of daytime ball games, fielders on both teams complaining to one another about the high sky and the white shirts—all foreshadowed disaster.

The tall, slender Davis could no longer see Blair’s fly. He scoured the sky, looked into the sun. His vision was obscured by a pulsating afterimage. Still, he held his position.

And then suddenly—too suddenly for the Dodger outfielder—Blair’s fly fell out of the sky. Davis spun, swiped at it. The ball trickled past him for an error.

In the press box, Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times punched the keys of his manual typewriter. “Paul Blair,” he typed, “hit what would have been a routine chance for anybody with fingers.” 15

Blair reached second. Powell stopped at third.

Murray pushed up his horn-rimmed glasses, drew on his cigarette, leaned back, looked at the field for a moment before continuing. “Sandy Koufax stands there like a guy who has caught his mother putting arsenic in his pablum.” 16

A scoreless game with one out and two on in the fifth. The young kid, the opposing pitcher, Palmer, was on deck. Alston and Wills convened at the mound to talk it over with Koufax. It was the same situation Baltimore had faced in the second inning: lumbering guy at third, poor hitter due up after this. Should they repeat Baltimore’s strategy? Should they walk Etchebarren and load the bases to get to Palmer? They decided that Etchebarren himself was a pretty weak hitter; he’d looked bad striking out in his last at bat. They would just pitch to him. 17 The decision looked brilliant when Etchebarren proceeded to punch a soft fly to short center. Willie Davis appeared to have this particular pop-up handily under control. Catching an early glimpse of the ball, he raced in.

Watching from Baltimore’s coaching box at third base, Billy Hunter recalled Jim Russo’s scouting report on Davis. “When running laterally, his throws have nothing on them. He usually flips the ball side-arm and misses the cut-off man.” 18

Hunter ordered big, slow Boog Powell to tag up and prepare to break for home. Powell did so, directing his gaze toward the outfield to watch the fly descend.

But this time too Davis had lost the ball. It had climbed like the last fly, and then just vanished into the sun. He looked up at the sky imploringly, spread his arms wide, Job-like, beseeching. Willie recalled saying to himself right then, “Shit, here’s that same kind of ball.” 19

The crowd held its breath. A few awful seconds passed, then the horror-struck fans saw the plummeting ball hit Davis in the heel of the glove and fall at his feet.

“I’ll be honest with you, I wish both of them had been caught,” Koufax would tell reporters afterward, “but they weren’t. It’s just one of those things.” As always, the remarkable Koufax would be as forgiving of his teammates as he was unforgiving of himself. “I wasn’t bothered by what happened out there… but it sure makes it tough on you.”

Powell scored. Seeing Blair break for third, Davis snatched up the ball and flung it wildly to Gilliam. It sailed high over third base. While Koufax ran to retrieve it, Blair scored.

“The Baltimore dugout was stunned,” Jim Palmer remembered.

The ballpark spectators complained loud and long, while the customers at Kirson’s danced and cheered. A bartender snatched up a piece of chalk, skipped gaily across to the scoreboard, and put up 2 for Baltimore, 0 for Los Angeles.

The Dodger center fielder was charged with two errors on the play, a total of three errors in the inning. (A Drabo-worthy record, before yesterday.) Etchebarren was on third, and there was still only one out.

Vin Scully provided a literary perspective for those watching Willie’s error-plagued play on NBC. “Brings to mind a line,” Scully mused, “I think it might have been written by Jim Bishop, or perhaps he was quoting somebody when he wrote, ‘Only saints want justice. The rest of us want mercy.’ Well, I’ll clue you, Willie Davis is on that mercy handout line right now.”

Actually, most of the Dodgers agreed that Willie was the only one among them who would waste no time or effort seeking mercy or sympathy. “Willie, you know,” Tommy Davis would say later, “he was cool.” 20

“If that was to happen to anyone on our team,” Wes Parker agreed, “I would’ve picked him, because he probably could have handled it the best. He didn’t have a real conscience about his play. He was a go-with-the-flow kind of guy. Whatever happened, happened. Anybody else who’d made three errors in one inning in a World Series would have been devastated. I know I would’ve been. It would’ve bothered me the rest of my life. But Willie, it just rolled right off him.” 21

Baltimore wasn’t finished. After Jim Palmer struck out, Aparicio followed with a double down the left-field line, scoring Etchebarren from third. Blefary flew out to Fairly in shallow right to end the inning. Baltimore led 3–0.

As Davis trotted to the dugout, the fans on the third-base side roared their displeasure. About ten feet from the dugout, he tipped his cap. Later, Willie would explain to a reporter, “I was just sort of telling the crowd—you assholes.” 22

Davis found Koufax in the dugout and immediately apologized for misplaying both pop-ups. “They both came out on the same angle.”

Sandy put an arm around the outfielder’s shoulders and shook his head. “Don’t let it get you down.” He smiled. “These things happen. There’s nothing you can do.”

Don Drysdale piped up, “Hell, forget it. You save a lot of games for me with great catches.” 23

When Willie was late to emerge from the dugout after the inning, one reporter in the press box asked another, “Do you suppose he may be about to commit suicide?”

“Hope not. He might miss and kill an usher.”

“Koufax,” another newsman recommended, “ought to soak Willie’s head with ice today instead of his own elbow.”

“I wonder if Davis will be able to catch the plane to Baltimore,” a third joked. 24

And Willie’s reputation was about to take another hit. Frank Robinson led off the sixth inning with a high fly ball toward right-center. Davis and right fielder Ron Fairly converged on the warning track. Fairly was cautious, assuming that Willie would want to glove this easy fly just to show the fans that he still knew how. But “as it turned out,” Fairly would say later, “he’d already made three errors, he was afraid of making four. That might have been going through his mind.” 25 Too late, Willie called for Fairly to make the catch. The ball fell between them and bounced to the wall.

Robby dug around second, kept going. He ran like a guy hurting. He slid into third, his uniform taking on a great deal of dirt. Fairly’s throw was relayed home. The crowd booed madly.

Frank, tired and noticeably hobbled, instantly leapt up and began brushing off his pants. When he’d fallen down in the second inning and missed picking up Lou Johnson’s single to right, and then when he’d been picked off second base to end the fourth inning, he’d been worried that he would be the goat. But thanks to Willie Davis, Frank’s miscues would go completely unnoticed.

Brooks Robinson fouled to Parker for the sixth inning’s first out. Then Boog singled, and Frank, using his arms to do most of the work, jogged home to clamorous cheers in a faroff bar: 4–0, Baltimore. Davey Johnson followed with another single, this one off a rare Koufax forkball. It scooted speedily past Parker into right field, rolling into the record books as the last hit Sandy Koufax would ever surrender. (“That’s why I knew I was washed up,” Koufax would tease Davey afterward.) 26 To memorialize it further, Ron Fairly scooped up the ball and hurled it frantically toward third. It bounced past Gilliam for the fifth error of the game.

Koufax intentionally walked the next batter to load the bases for Andy Etchebarren, who kindly sent a grounder to third. Gilliam snagged it, fired it to Roseboro ahead of Boog Powell. Roseboro wheeled, fired it to Wes Parker ahead of Etch. A double play. The Dodgers were out of the inning.

Vin Scully had been keeping the patrons at Kirson’s—along with the rest of the estimated twenty-five million people watching on television—abreast of Koufax’s condition. The redheaded broadcaster had seen every pitch Sandy had thrown in his major-league career, had watched him since he was skinnier even than young Jim Palmer—just a nineteen-year-old recruit in a baggy Brooklyn uniform. He could pinpoint the signs of a fatigued Koufax, and he shared them with the viewers: the extremely long stride, the stumble after releasing a pitch, the arching of his back instead of following through. The exceptional elegance of the southpaw’s windup; the splendor of his uncoiled, full-bodied, bow-backed delivery; the beauty, the grace, and the poise—all were in complete contrast to the grimace of utter agony Scully saw, more and more clearly, clouding Koufax’s countenance. By the end of the Baltimore sixth—the 330th inning Sandy had pitched that season—he felt the weight of every pitch as his body began to tire. The baseball grew as heavy as a brick. He was drenched with perspiration. His game face had become a shifting series of death masks—a rotation of agonized expressions, reminiscent of a saint preparing for martyrdom. He was so clearly struggling that it surprised no one when Ron Perranoski walked in from the bull pen (to the stadium organist’s accompaniment of “Hello, Dolly!”) to start the seventh.

Koufax had allowed just one earned run, but he left the game behind by four.

Some loud person at Kirson’s shared the opinion that God was involved, that he was punishing Koufax for pitching on October 6, a Jewish holiday. 27 His bar mates nodded, warmed by mugs of draft beer and the notion that here the Lord was, at last taking pity on Baltimore, finally siding with those less fortunate. It sounded right. Hadn’t Koufax refused to pitch the opening game of the World Series against Minnesota on October 6 of the previous year, on account of it being Yom Kippur? Everybody knew the story.

Koufax had not played out of respect for the Jewish Day of Atonement, his religion’s holiest day. And the Dodgers had lost. He’d pitched the next day, but his team had lost again. He’d gained another chance in Game Five and shut out the Twins, and he’d pitched in Game Seven and shut them out one last time. It was the stuff of legend, a religious miracle. In one week, he’d gone from sitting to losing to winning to earning, on two days’ rest, the world championship.

And now here he stood, pitching on October 6. What, did he think the Lord was no longer watching?

Not exactly. On the lunar calendar observed by the Hebrews, Yom Kippur always occurs on the 197th day of the year (the tenth day of the seventh month). In 1965 the Jewish calendar had begun on April 3, so Yom Kippur had been celebrated on October 6. But in 1966, the Jewish year had begun on March 22, and Yom Kippur had fallen on September 24. The Dodgers had been in Chicago, and indeed Sandy had not pitched.

Something about Koufax’s delivery seemed guaranteed to ensure that he would leave behind disputed memories, stories swirling in mythic mists. No photo of him in action was without a blur somewhere. Even after Koufax tired that afternoon, he continued to throw so fluidly that by contrast, Palmer’s delivery appeared to be jerky, a shuddering series of still lifes. The young right-hander would lift his hands and left knee; he’d bend his right knee, rear back, peer over his shoulder; he’d point his index finger and fall; he’d twist, come over the top. After walking two in the second inning and escaping unscathed, Palmer promptly settled down. With hard fastballs and a couple of sliders, he calmly retired the side in order in the third and fourth, gave up a meaningless single in the fifth, retired the side in the sixth.

In the Dodger seventh, he fanned Jim Lefebvre for a second time. Lou Johnson followed by drilling a sharp grounder to third. Despite charging down the first-base line, Sweet Lou was thrown out. Palmer had completed six and two-thirds shutout innings, duplicating Drabo’s feat of the day before.

Over two championship seasons, Johnson had been the team’s buzzing dynamo. His electric presence and timely hitting had opened holes, created possibilities. Now, jogging across the diamond to make his way back to the home dugout, his shoulders drooped. Head down, he grew pensive, slowed to a stroll. The home plate umpire stood, as did Etchebarren. Palmer stepped off the rubber to stare. The game was momentarily held up while this morose spectacle ambled past.

Nothing could have better communicated how lost the home team felt at that moment. The great Koufax was already in the clubhouse, elbow packed in ice, and Baltimore had just broken Sweet Lou’s spirit. Registering all this from the Oriole bench, another Johnson, reserve infielder Bob Johnson, nodded with satisfaction. “I think we have them now.” 28

And indeed they did. But first, with two on and one out in the eighth, relief pitcher Ron Perranoski threw away a ground ball for the sixth Dodger error of the day, making the score 6–0. Appearing as a pinch hitter in the bottom of the eighth, Tommy Davis singled and moved to second base on a wild pitch. It would constitute the last Dodger threat of the day. Though stadium organist Helen Dell tried to rally the hometown boys by playing “Bye Bye Blues,” “With a Little Bit of Luck,” “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” and “Great Day,” it was all to no avail. Tommy was stranded at second, and after Roseboro popped up to Aparicio in the ninth, it was over.

With two out and one on in the ninth, Baltimore’s twenty-year-old Jim Palmer prepares to retire his final Dodger in Game Two. (AP / Wide World Photos)

After the game, a reporter asked Palmer, “Having won the first two, where do you see the Series going from here?”

“To Baltimore,” the kid replied. 29

Los Angeles mayor Sam Yorty, a sudden but fervent Dodger booster, turned away from the game in revulsion, as if personally implicated in the loss. The mayor’s life would never again be so blessed. He would be narrowly reelected three years later, but only by running what his opponent’s campaign manager would term “the most racist campaign in the history of California.” It would be the last election ever won by the perennial candidate. Ultimately, a survey of civic experts, urban historians, and political scientists would judge “the Little Giant” to be one of the most callous officials of the turbulent 1960s and one of the eight worst American big-city mayors since 1820.

Jim Palmer, however, was a winner. Somehow, despite the sour pitching arm, he had done it. He’d announced that he could beat the Dodgers with a fastball, and indeed he had. In so doing, he had delivered not only the first shutout of his career—and in the World Series, no less—but also his last good outing for quite a while. His arm would take a long time to recover, and Palmer would spend most of the next year in the minors, just trying to throw half as well as he had that Thursday afternoon against Los Angeles.

The game was also the last one Sandy Koufax would ever pitch. It was his fourth start in eleven days and only his third start since mid-August that he didn’t finish. He lost by his biggest margin of the season. “What did he get, two strikeouts in six innings?” Robby asked afterward, having gotten the better of their historic matchup by walking, tripling, and scoring twice. “That’s not Sandy Koufax.” 30 Lacking the ability to strike men out, Sandy had relied on his teammates to play their usual sterling defense. Instead, Jim Gilliam had bobbled grounders, Willie Davis had lost balls in the sun, and Ron Fairly had pulled up short. Balls had missed gloves and cutoff throws had sailed high. And so he had lost.

Boarding the airplane to Baltimore immediately after the game, Sandy was flagged down for one last TV interview. “Were you disappointed by the play behind you?” asked the interviewer.

Koufax had done little but quash that question for an hour. This time he said nothing, just glared at the reporter.

“I mean specifically Willie Davis.”

Sandy studied the man icily, color rising in his cheeks. He held his tongue.

“I can stand here as long as you can,” the reporter challenged.

Finally, Koufax lost his composure. “What are you trying to get me to say?! No! I wasn’t disappointed! Without Willie Davis we couldn’t be here in the World Series! We never would have won the pennant without Willie!” 31

That may have been an overstatement, but it was indeed true that Willie’s homer in the season’s final game had cushioned their lead over Philadelphia. Unfortunately for Los Angeles, as a consequence of that blast, Davis now perceived himself to be a home run hitter and would spend the postseason working without success to prove it. Batting near the top of the lineup in every game, he would hit just .063 in the 1966 World Series.

Having given the reporter a piece of his mind, Koufax spun on his heels to join the others on the plane.

By the time Vin Scully and Bob Prince signed off on their respective broadcasts, the record 55,947 fans had filed numbly out. Even the knowledge that they had helped shatter previous attendance records meant nothing. (Although all Series games played at Dodger Stadium were sellouts, somehow, conveniently, this particular sellout crowd had been declared the biggest in stadium history.) Their mood was as limp as the pennants that drooped like wilting sunflowers from their hands. The aftertaste of peanuts and Cracker Jack was like ashes in the mouth. Prior to one P.M. yesterday, their boys had never dropped a World Series game at home. Now, appallingly, they’d lost two, back-to-back. Among the departing spectators shuffled Casey Stengel and a slew of frowning Tinseltown celebrities. But in the expiring light over Chavez Ravine, neither Stengel’s muttering disgust nor the disappointment clouding the lovely faces of Hollywood’s cinema stars would prove the fitting symbol for this, the West Coast’s final championship baseball game of the decade, the last game of the country’s most popular athlete, the end of an era.

In the crowd that day were three men who sat ramrod straight in the commissioner’s box, watching as guests of baseball’s number-one military man. In the bottom of the second inning, the three were introduced to great fanfare. They were to be the first Apollo astronauts, and one among them, their legendary leader, Gus Grissom, had been assured privately by NASA that he would be the first man on the moon. 32 A few months later, however, during a simulated launch, all three men—Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee—would die in a fire aboard their Apollo spacecraft.

Soldiers, astronauts, and baseball players—uncomplicated heroes; fit, short-haired, clean-cut, steady-eyed, and mostly white—appeared to be natural extensions of one another for the last time on that day in early October. That game was over, too.

Koufax departed, and night fell.