The Crystalline Sarcophagus

Illustrated by Malcolm Smith. (First published on May 1947

)

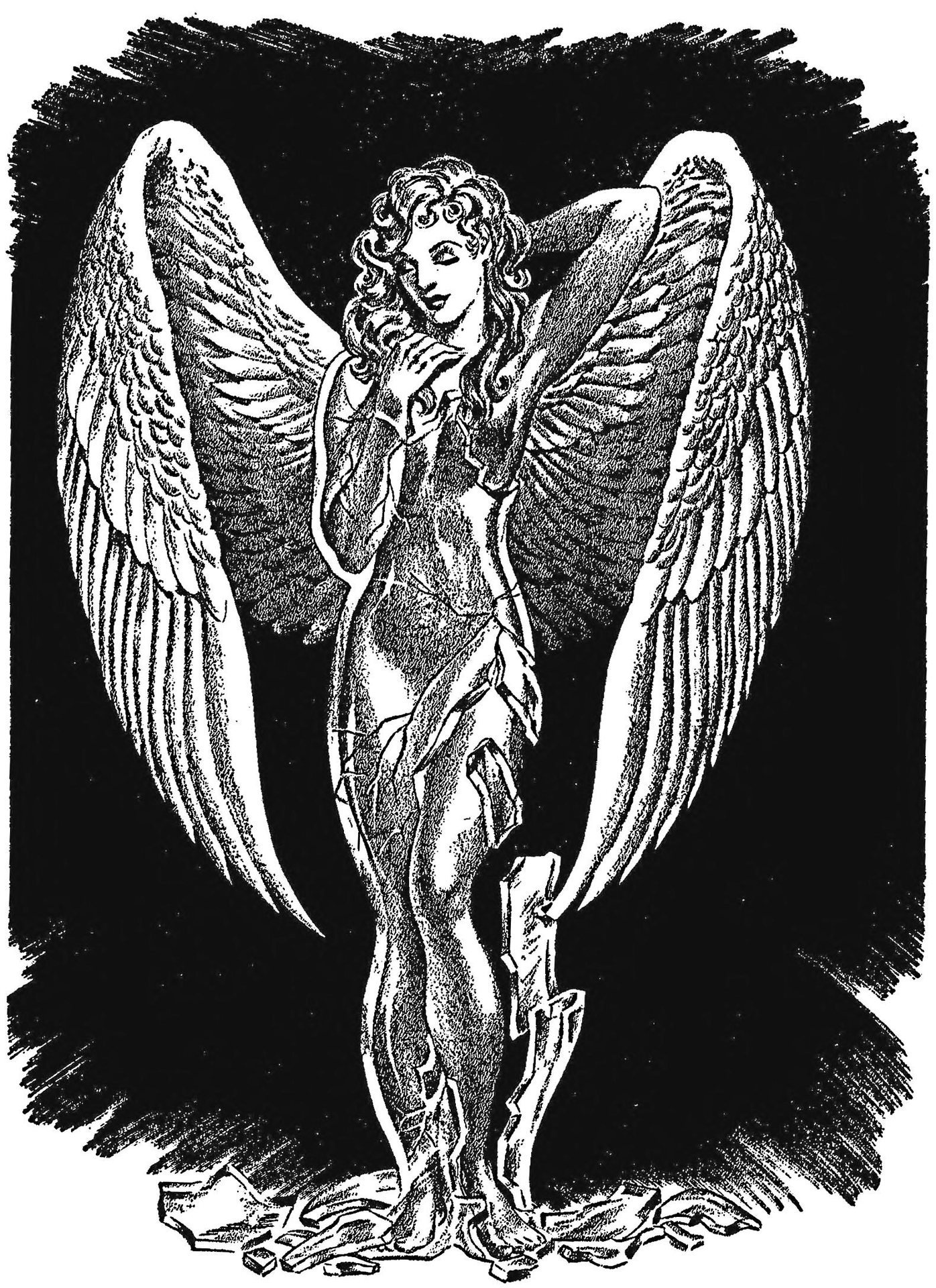

Doctor Moorehead was engaged in a weird experiment—which some said involved a corpse. But what if the corpse turns into an angel?

O

LD Man Sickler was a town character. He had a face that was a study in red and brown, and a mop of gray hair that stood up on his head at the mention of an argument.

He lived in a little shack near the edge of town. He didn’t pay much attention to being clean, or keeping his hair cut, or keeping his mouth shut. But I learned he could

keep his mouth shut when the need arose.

Lately, Old Man Sickler had a bee in his bonnet about Doctor Moorehead. The Doc had a big gingerbread mansion next door to Old Sickler’s shabby four room shack up on the hill at the end of Main Street. A sign on the learned Doctor Moorehead’s front porch proclaimed him to be a research physicist. The house was surrounded by large elms and sycamores, and the Doctor was always busy inside at something or other. He didn’t walk out much, and when he did, he walked fast. All attempts to draw him into conversation failed; the Doc just gave the inquisitors a brisk “Good Morning” and kept on walking. So, nobody in town but Old Man Sickler was very well acquainted with Doctor Moorehead, though I doubt anyone had ever pointed that fact out.

The Doctor, like others in town, seemed to take a delight in giving Old Man Sickler something to puzzle about; to “get him going”. He would tell Sickler some impossible rigamarole full of scientific terms, and the bunch in the drugstore would howl when Old Man Sickler tried to repeat the Doctor’s words. This habit of the Doctor’s was the thing that made us almost miss the biggest thing that ever happened in our town of Bersburg. When Old Man Sickler tried to tell us of the disappearance of the old lady, of the reappearance of a young girl in her place, and finally of the “glass coffin,” we all thought the Doctor was having more fun at the old man’s expense. But this night it was different.

This night Belle and I were standing in the drug store, debating on a movie or a swim to finish off the day, when old man Sickler came in, his mop of gray hair on end. He didn’t wear a hat. The night outside was heavy with the smell of the young summer’s leaves; and Old Sickler, with the garden soil on his heavy shoes, brought some of the scent of growth in with him. Everyone turned and waited expectantly to hear what he had to say. But he wasn’t having any tonight.

“I want some of them Je Jay Corn Plasters, John,” said Sickler to the druggist. The, druggist winked at me, his pimply face impish, and I cocked an ear.

“Okay, Mr. Sickler. Right away.” John fumbled around under the counter, though the plasters were in plain sight. I knew he was figuring on getting the old fellow wound up, for the little town didn’t furnish much excitement

and this was a chance to get a little relief from the monotony. Still fumbling, the druggist started on a topic that was calculated to arouse the old man.

“How’s the Doctor and his corpse coming? Any new developments?”

The old man rose to the bait nobly.

“I know you don’t believe me, but I know what I saw with my own eyes. I went over and peeked in the window just afore I came down town. Yessir, that’s the funniest thing I ever seen in my life. You know what he’s done now?”

“No, what has he done now? I wouldn’t put anything past him. Those dark eyes of his, and that slick shiny hair, and the way he walks around too good to talk to people. Tell us about it.”

John wouldn’t have said that sort of thing for any reason but to lead the old man on. He was only repeating the old man’s talk about the Doctor.

“He’s got the woman all plastered over with some kind of soft, glassy stuff. Yessir, she’s just like a mummy in a crystal coffin. Funniest thing I ever seen. And only last week I would have sworn she was alive and breathing. Now she’s wrapped up in glass, as tight as if it was poured around her. I think it was

poured around her, hot glass, and her alive while he done it. If he ain’t a kind of a Dracula or a vampire or something, what became of the old lady that used to be there with him. What become of her?” For some reason the druggist realized that that kind of talk might go too far, and said:

“Why you remember where she came from, Mr. Sickler. She was the only stranger came to this town to stay in quite a while. That woman in the bed is the little old lady, came here to take treatments from the Doctor. Now she’s died and the Professor bought her a glass coffin. Don’t you think that’s it?”

The druggist was evidently not believing the old man, but willing to hear it if there was any more to be heard. I listened, too, for it did sound eerie, with Sickler’s wild old eyes rolling and his whisper hissing through the drugstore. Next to me the cabby looked up from his comic sheet. Sickler’s whisper went on, loud enough to be heard in the next block in this quiet town.

“It can’t be her, John. She was old, and the woman in the glass don’t look a day over twenty. And she ain’t got nothing on her, under the glass. And the Doctor stands over the case, worried like, listening with his stethoscope and his electric meters, making a fuss over a dead body. What kind of goings on is that, now? Besides, whatever became of the old lady? I ain’t seen her around for six months. Have you?”

The cabby, who had evidently absorbed the conversation from the beginning, spoke up.

“I never took her away, John. And Moorehead doesn’t have a car. I never could figure where she got to myself. There’s no other cab in town that I know of. She might have walked down to the station herself, but someone

would have seen her and mentioned it. You know how it is, she was almost the only stranger in town. Besides, she could hardly walk when I brought her here. Had to help her out of the car and up the Doctor’s steps.”

Old Man Sickler got in a lick.

“That Moorehead ain’t rightly a Doctor, anyways. He never Doctored anybody I knowed of. And that sign on his front porch ain’t a Doctor’s sign. ‘Physikist!’ That ain’t ‘Doctor,’ to me.

The druggist looked at me.

“Well, I’ll be darned.”

It was

getting a little steep for joking.

Sickler started out the door, shaking his head.

“Darn funny doings, if you ask me. He might have killed that old lady, for all we know. He looks like some dinged fancy murder feller to me, anyways. I heard him laughing to himself when there wasn’t a soul around to laugh at. This gal he’s got wrapped up in glass might be the old lady’s daughter, come to see what become of her mother. How do we know? You don’t keer a darn, but I live next door. Why, the Prof. might decide I knew too much, or catch me peeping in the window at his glass coffin, and bump me off, too.”

Sickler went out into the soft, leaf-scented night, his garden boots clumping loud in the stillness. I looked at Belle.

“Just what

do you make of that?

”

“Frank Mellon, I think it’s a crazy old man talking about things he imagines. That’s all it is, and you know it.

“The cabman isn’t crazy, Belle.”

Right about now I better introduce myself and Belle. Belle is a good-looking redhead of twenty-two or so who does all the typing for the office of the Bersburg Clarion

. I’m the inquiring young man about town who writes all the stories that give the town something to gossip about. The town doesn’t like me very well. I once said the place was full of snooty old busybodies, and they all took it as a personal affront when it got around. I must have been right! But my old man owns a large block of the stock of the paper and they can’t get me fired. We usually met in the drugstore, Belle and I, because Old Bill Mercer, Belle’s dad, doesn’t like me any better than the rest of the town.

I was interested, more than I cared to say, in what I had heard of Moorehead tonight.

“Look, Belle, suppose you and I take a walk up to Old Man Sickler’s place and get him to show us the window he used to see all this through? There just might

be something worth seeing.”

“And suppose we don’t. Doctor Moorehead could get right angry at such

snooping if he caught up. And the Clarion would have to fire me, if they can’t fire you. And a girl has to eat.”

“Swell. Then we’d have to get married right now, instead of putting it off ’til we’re old and grey. Come on!”

As we passed the fountain mirror, my tousled black head beside her gleaming red tresses; my rough, heavy features beside her chiseled, smooth sculptured face; were a contrast I never failed to notice with a strange thrill of possession for her beauty.

* * *

Old Man Sickler pushed his shaggy grey head through the rhododendrons ahead of us. We stooped and followed him through. Up against the side of the house, we raised up and looked in the window, following the old man’s pointing finger. The shutters were closed inside, but you could see between the cracks if you put your eyes up close to the window. Belle and I both let out our breath in a double “whoosh.”

In the middle of the big room was an old four-poster bed. A soft light glowed over the bed. On it was a something

. A something

that our eyes refused to believe.

Around the room was a lot of apparatus, not particularly understandable, but all looking somehow familiar, as if one had seen all the parts in the college lab. Stills bubbled over bunsen burners, several big condensers hung from the bars of the metal stands, and on the three tables was an array of electrical apparatus that did not look familiar. Decidedly not.

But the figure on the bed eclipsed all this array of scientific paraphernalia. Like Old Sickler had said, it was a young woman in a glass-like wrapping. It seemed to have been poured about her in a liquid state, for it fitted her apparently nude body exactly. She looked like some weird statue of glass, tinted inside with the colors of life. But about the thing was an air of life, a terrible significance I could not quite grasp. This terrific meaning struck one as if one had peered for a moment into another world. For that semitransparent glass wrapping had the markings, the peculiar conformations, of a human chrysalis. And within it breathed the thought of life. The woman was not dead; one felt it. If a human body was not a human body, but something insect-like that had formed a chrysalis—this would be what it looked like.

My mind raced furiously. Why should anyone want to build a glass sarcophagus, a coffin for anyone—and why should they shape it to the body so suggestively as to intimate that the body was but sleeping within a cocoon? It was perhaps a poetic kind of burial we were witnessing. But this line of thought was quickly discarded by me when the Professor entered the room.

Going up to the body, he took a stethoscope from the table and bending

over the lovely sculpture on the bed, listened for long minutes to the heart action. How could there be any heart action in a woman enclosed in glass?

Belle and I looked at each other. Nonplussed was no word for it. We were just plain stumped. What we were looking at had no parallel, nothing comparable by which our minds could evaluate or decide, no course of action suggested itself to us. We stole silently away again, bade Old Sickler a mumbled good night.

Nor did we write it up for the paper. We just kept quiet and waited. After that Belle and I formed a habit of going up to Old Man Sickler’s on the sly and taking a look through the shutters at Professor Moorehead’s secret mummy. It wasn’t a mummy though. It was the livest looking corpse I ever saw.

Summer dragged into Fall, the leaves began to burn into vari-colored carpets on the ground, the persimmons ripened in the first frosts. There wasn’t much cover left in the leafless bushes for our sneaks into Prof. Moorehead’s grounds, but we went anyway. We took a couple of our friends into our confidence, but had no ideas on what a man should do when confronted with the inexplicable. So, our trips to Mooreheads sometimes included a friend or two, just to “prove it to you.”

Old Man Sickler was in his glory, but he heeded our advice not to talk about it, for it was something we couldn’t understand. We couldn’t say the Doc. was guilty of anything, for we didn’t know enough. You would think we would have found a chance to talk to Moorehead about the thing on the bed, but he didn’t give us much chance. When he walked, he walked fast, and he didn’t stop to chat. A frozen, abrupt “Good Morning” was all we ever got out of him, and he was gone again on his walk.

By this time there were a couple of dozens of us in on his secret. He must have got wind of our spying some way. Perhaps he noticed our tracks in the soft ground of the rhododendron beds. Anyway, one Friday night in early October we were stooping through the bushes when a harsh voice cried out to us.

“Who’s there? Come out into the light and let’s have a look at you.”

We came. The Doc. didn’t sound like a man to argue with. Besides he might have a gun. There were only Belle and I that night. Old Man Sickler had stayed in his house with the “rheumatiz.” I was glad there was no one there to complicate the soft soap I figured on giving the Prof. with a lot of foolish accusations. I wanted to know what it was all about. So, I straightened up and talked. It was high time somebody did.

“Professor Moorehead, we have known for some time what a curious object you have there on your bed. We have seen you listening for the heartbeat and—other things . . . Our curiosity is too much for us. Not knowing

how you would receive our intrusion; we did not care to risk losing all chance of seeing just what your work was leading to. Will you take us into your confidence?”

“You mean to say you have known for a long time?” The Professor was taken aback. His sharp, bony face softened. The black deep eyes with the worried frown between looked closely at us, as if trying to recall where he had seen us.

“You are two young people who work for the local paper. Why haven’t you put your information in your cheap little sheet?”

“Well, Professor, we didn’t want to go off half cocked, and we didn’t want to embarrass you in case you were innocent of any wrong intent. We have been waiting for a chance to sound you out without revealing our hand, but somehow it never came.”

“Come in. I can see you deserve an explanation of these things that puzzle you. I must say you have shown admirable forbearance in keeping your mouths shut about things you didn’t understand. I offer my gratitude. Whatever led you to withhold action on this—let me tell you, you did the right thing.”

We followed him into the long front hall, with the old but expensive carpet running up the winding, beautiful open staircase, with the great grandfather’s clock ticking, and the indirect lights from the recently installed modern fixtures making the place pleasant and far from any gloomy Dracula’s hangout. He seated us in the adjacent drawing room, calling it the parlor just as we would have. Then he lit a cigar and began to talk. We listened. Maybe we understood and maybe we didn’t. I hope we did, for it means so much to man to have Dr. Moorehead right.

“To explain what you have seen, I will have to give you a little talk on science. Follow closely or you will not understand.

“You see, it is not true that men do not know the cause of age. It is

true that they do not know they know

the cause. But perhaps I had better give this talk where you can see the object in which you have been so interested.”

The Professor led us into the room which we had already seen so often through the drawn shutters. On the bed lay the crystalline sarcophagus, a thing of breath-taking beauty, much more so now that we were close.

“This woman was once a great beauty, and quite famous. I cannot tell you her name, she would rather not have any publicity. Now that this particular angle has developed, I doubt that publicity would do either she or I any good. Anyway, she consented to be the subject of my experimental proof of the efficacy of my treatment.”

“Professor Moorehead,” asked Belle looking thoroughly confused, “What did you intimate by saying this woman was

once a beauty?

”

“Her age was over seventy-five when I first began my work. She has been under treatment a little over a year. You can see the results, so far as age goes, in her youthful appearance. But this crystalline pupa is, frankly, something I do not understand. It is entirely outside my experience. So it is that I find myself with a problem too big for me to solve.”

“I don’t quite understand.” Belle was confused, and myself saw no light evident that would lessen her confusion. I could only guess at what the Professor was driving.

“Just what is this treatment you speak of?”

“It has to do with a new theory of the cause of age. It is my own theory, but the treatment I eventually adopted for use on aged people is not my own. You see, I deduced that age was due to radioactive material accumulating in the body over the whole lifetime—a gradual radium poisoning. Madame Curie herself died of a complication resulting almost directly from radium poisoning. She would not have died had I been there.”

Belle was intensely interested and beginning to get a glimmer. I had a few ideas myself, but not the audacity to open my mouth for fear of putting my foot in it.

The Professor looked at Belle with a kindly, thoughtful expression. Belle asked:

“You say it is not your own treatment. Just what do you mean? If it made this woman young, why did she have to be enclosed in glass? Is she dead?”

“You see, my understanding of the cause of age is new. The treatment which I use for rejuvenation was developed by others for the purpose of treating victims of radium poisoning.(1)

I adopted the treatment of aged people when I proved to my own satisfaction that age is caused by radium poisoning. Radium is thrown here every day from the sun. We eat it, we drink it, we breathe it with our air. So, we age and so do all living things.”

(1) If radium is eaten, drunk in radioactive water, or breathed into the lungs with air, it tends to be deposited in the bones, and begins a slow poisoning process which will be fatal if enough radium is present. Though radium is extremely expensive, ten cents worth is enough to kill a man if it gets into his bones. Eating five dollars’ worth, or breathing fifty cents worth of radium salt will accomplish this. As little as one ten-millionth of an ounce of radium deposited in the bones has been found to cause death within ten years. — “Atoms in Action” by George Russell Harrison.

“Your theory sounds probable. I have myself wondered if there were not more effects from the sun than a tan—if science could but discover them.”

I was very anxious to find out just how all this explained a glass wrapping

around a young woman—a young woman who had not been young before, but now had every appearance of youth.

“It is true that the sun is the cause of age in all living things, including plants and trees. I have proved it. One of the ways I proved it was by curing it.”

I gasped.

“You cured age! I can’t believe it. Are you serious?”

“I studied the treatment for radium poisoning, used it on experimental animals, who were not poisoned by radium, but were aged. They became startlingly younger, and the longer they took the treatment, the younger they became. But certain other very puzzling changes came about. I cannot fully understand them. So it is that I could not give my work to the world. Not until I understand why these things happened.”

He paused musing—then said:

“Come with me, I will show you some of these things that puzzle me.”

As we walked through the house and out to a building in the back of the grounds, my curiosity made me ask him one more question, instead of waiting for his own explanation.

“Doctor Moorehead, just what is

the treatment for radium poisoning?”

He was not at all loath to talk. He said:

“Radium is chemically like calcium.(2)

Bones are made from calcium, and the unsuspecting bloodstream willingly deposits radium atoms wherever calcium atoms are needed for building purposes. The only cure for a person suffering from radium poisoning is to get them out—find a method of removing these radium atoms.”

(2) Radium is chemically like calcium from which bones are made and the unsuspecting blood stream willingly deposits radium atoms wherever calcium atoms are needed for rebuilding purposes . . . In a number of cases of radium poisoning, it has been found possible to literally rinse some of the dangerous atoms out of the patient’s bones. First, he is given a medical treatment which causes his bones to lose calcium, and as the calcium departs, some of the radium is forced out with it, in keeping with its masquerade as calcium. Before his bones are appreciably softened the treatment is reversed and the body is encouraged to take up fresh calcium to rebuild them. —Harrison’s “Atoms in Action.”

“That sounds like a pretty impossible job.”

“At first glance it does seem impossible. But in practice it is not at all. It has been found quite possible

literally to rinse

the dangerous atoms out of the patient’s bones! First the patient is given a medical treatment—a diet— which causes his bones to lose calcium. This diet is really only food high in vinegar content—and other acids like vinegar which have a natural affinity

for calcium. I give such a diet for a week, then I give normal food for a week, except that I put in the food chemically pure calcium which I test myself to make sure there is absolutely no radioactivity present. It sometimes occurs in almost any material that radioactivity is present. The vinegar and acid diet has a relatively low power to harm the body, and the calcium goes out with it. Some of the radium goes out with the calcium, still masquerading as calcium, due to its valence. I continue this treatment, in the case of my human patients, for eighteen months, alternating each week from acid to calcium. Simple is it not.”

“You mean to tell me that is all there is to it?”

“Except for extreme care, yes, that is all. But complications have developed. Look at these animals. They are animals once feeble with age. Now they are young and active, extremely healthy. But some of them go into incubational pupa stages which are not natural to the animal as we know it. It is beyond human experience. That is what happened to my first human patient. See—here is an animal which I treated over a period of years with the alternate removal and replacement of calcium diets. Everything was fine until one day he went to sleep. A chrysalis formed about his body, and when it opened—that came out. Do you recognize the animal?”

He was indicating a cage containing an animal with four long legs, clawed like a cormorant, a pair of delicate membranous wings of giant size, and two huge eyes that gazed at us mournfully.

“I can’t say I ever saw anything like it. What is it?”

“It is a guinea pig. That is, it was before this happened. In the case of my human patient, I explained these strange developments, and she begged to go on with the work. Now the chrysalis has formed about her, and God alone knows what time will bring forth from the human chrysalis.”

There were dozens of other animals about the building, in cages. But hardly any of them were recognizable. Did you ever see a cat or dog built like the Sphinx? Well, I did. And after seeing him, I wondered if maybe the ancients didn’t have a little more to say when they built such ornaments as the Sphinx—a little more of a message for the future man than we have ever understood. Certainly, those animals such as Doctor Moorehead showed us told me that such things as the Sphinx could be.

My mind in a whirl at the terrific consequences that might come from world-wide knowledge of Moorehead’s methods, I followed him back into the house. Belle’s soft arm was clutched tightly about my own, her usual self-confidence dashed by these revelations to a silent wonder.

As we walked back through the house the Doctor stepped once more into the room where the young woman lay wrapped in her blanket of

crystalline sleep. We stood behind him, silently gazing on the mystery that life had suddenly become. And as we looked at her, a tremor shook the crystalline casing of her lovely form. A crack appeared down the clear sheen of the crystal from the forehead to the breast.

The Professor bent over her, reverently, fearfully. She was as beautiful as a dead goddess. A long, slow writhing shook the lovely body. She seemed, within the cloudy transparency of the sheathing, to be waking, struggling against her sleep. Her body began to pulse slowly with a pink suffusion of new life.

As we watched, the first faint stirring spread, her arms thrust outward. The crack widened, and abruptly the upper half of her case split wide open. From it her head and shoulders shrugged outward, and the unconscious writhing, the sleepy twisting, spread through all her figure and increased in a vibratory way.

Her eyes opened, looked at us as the eyes of a child do when they say that Heaven can be seen through the eyes of a child. Her eyes were like that, innocently questing, and bringing forth in me every noble impulse to do the right thing.

We dared not move. We were watching something no man would have the temerity to interfere against. Her whole body shrugged itself free of the plastic enclosing her, and she stepped forth alone as the Doctor sprang to assist her. As he did so, standing by the couch and turning, she shook herself, and behind her—behind her!

—great pinions unfolded and her broad wings swung quivering behind her, moist but swiftly drying to a beauty of hue never seen on bird before. In a short time, she stepped toward us holding out her hands. Her voice was husky.

“Doctor Moorehead, I am glad everything has turned out so well.”

Moorehead was not exactly astounded, his expression was more that of a man whose choicest hopes have suddenly been proved sound and feasible.

“Madame De Ronde, I am glad to welcome you to earth as the first angel to be seen by modern man!”

* * *

And that was just what we had witnessed, the rebirth of the angel. Once in the past when men had understood immortality, the highest cycle of the life of the animal man had been the winged man. Now, when men are mortal, none of them live long enough to fulfill the destined cycle of growth. But, given again the power of youth in age, the old inherited command to gestate into the higher state had come into being, and the body of Doctor Moorehead’s patient had responded. Angels were immortal women. She was the most glorious creature I have ever seen—and I know now what

the legendary angel was—the winged man that develops from the grub that men and women are today—and will be till they learn to live long enough to become the angel that is the full growth of man—as the past tells us. We watched the birth of an angel—a woman who had lived long enough to fulfill the great inheritance the blood of men still carries from the past—the angel that was our forebear.(3)

THE END

(3) The author is of the firm belief that the method outlined in the story for rejuvenation (the same method here outlined for radium poisoning) would result in rejuvenation—for the author believes that radium and kindred radioactives from the sun are the cause of all age in all living things. Of course, the treatment would have to continue over a long period of time. —Author.