Getting Organized

There are as many ways of organizing a piece of writing as there are writers and reasons for writing.

When an English teacher assigns sixth graders to write an English theme, they first have to turn in an outline that follows this form:

Introduction, stating a subject and a general idea about it.

Three examples supporting the general idea.

Conclusion saying, See, I told you so.,

This exercise—like the philosopher’s thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and the more elaborate outlines you get in high school, and the schemes that teachers apply to Faulkner’s short stories—is intended to train pupils in critical thinking, not to make them writers.

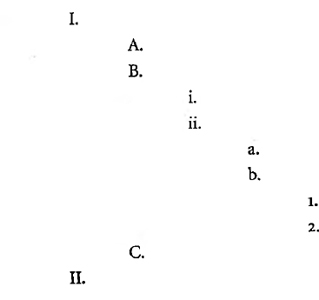

Of course, for some writers and some topics a formal outline is essential, and it may save time in the long run. The high school outline format,

and so forth, tends to force a writer to be comprehensive.

A writer of technical manuals has to integrate information on all the components of the device she’s describing. She starts with the smallest component and works her way up to the big picture, and she can’t miss a trick. This is the kind of orderly, comprehensive writing for which the formal outline was devised.

Likewise, a scientist knows what path he must follow in writing proposals for research grants. He has to make an extended argument, a syllogism, proceeding step by step from where the reader is to where he wants the reader to wind up, while anticipating objections.

Writing a short article needn’t require a very elaborate outline, but it may be useful to block it out in half-pages. If it’s going to be six typed pages long, you’ve got only half a page to do this, half a page to do that, and then half a page to wrap it up. But many writers, once they’ve finished school, may kiss the formal outline goodbye.

At lunch one day, Steve asked four professional writers whether they wrote formal outlines before they began to write their articles and books. They all said no. Three of them, though, said that they were always terrified of getting started. They sharpened pencils, worried about housework, stared out the window, and finally sat down and just started writing.

For many writers, the chief benefit of an outline is to get the process of writing started. That’s what Steve has found in his writing workshops. He breaks the participants up into small groups and asks each group to spend ten minutes writing an outline using one of six styles. In four of the styles, including the formal outline, you draw a picture of the structure of what you plan to write. The other two styles hardly seem like outlines at all, and they are effective in a surprising way:

Freewriting an outline. You write as fast as you can, scribbling, using abbreviations and incomplete sentences, not worrying about spelling, capitalization, or any of the formalities. Writers find this method to be fun and productive, and it helps to give them a broad overview of their project.

They seem to cherish ten minutes when someone tells them they have nothing to do but write. One woman said she hated writing, which turned out to mean that she dreaded having to be perfect. Freewriting gave her the chance to relax and get started without worrying about perfection. At the end of ten minutes she seemed relaxed and happy, and she had something on paper.

Dictating to others. The person dictating gets to spin ideas out orally, without worrying about how they look on the page, and at the same time she gets advice from others in the group. Again, the person dictating has the luxury of talking out her project during ten minutes set aside for that purpose.

To get some ideas about organizing your own writing, you can reread books, stories, poems, or memoirs you admire to see how they are organized. As an example, here’s a sort of free-flowing outline of one of the most admired of American memoirs, Alfred Kazin’s A Walker in the City. Kazin chose an unconventional organization for this book. It’s 176 pages long but divided into only four long chapters:

From the Subway to the Synagogue: A long, slow walk through Brownsville, the Jewish neighborhood of Brooklyn where Kazin grew up, from the subway stop that brings Kazin home from “the city” to the old wooden synagogue, only a block from where he was born. Drinking in the sights of the people, their activities, shops, and homes, and savoring all the food available on the street, and wondering about life outside Brownsville. Ending with Kazin’s confirmation at the local synagogue at thirteen and his resentment of “this God of Israel”: “He would never let me rest.”

The Kitchen: The busy hub of Kazin’s parents’ apartment in Brownsville. The place that “held our lives together,” where his mother prepared meals, where the family ate and observed Sabbath, where Kazin’s mother sewed and conducted her business as a seamstress, and where Kazin slept in winter, wrapped in a blanket across two or three kitchen chairs before the stove. The place where neighbors and customers, “women in their housedresses sitting around the kitchen table waiting for a fitting,” came in without knocking. “The kitchen gave a special character to our lives; my mother’s character.”

The Block and Beyond: The stores on Kazin’s block and getting a taste of the world beyond Brownsville. School trips to the Botanic Garden next to the Brooklyn Museum. Seeing the whales in the Natural History Museum. First seeing the Egyptian and Greek art in the Metropolitan Museum, and then, in a dim alcove, paintings of Kazin’s own city and Winslow Homers, Thomas Eakinses, John Sloans. Haunted by the blonde Mrs. Solovey, wife of the druggist on the corner, who looked exotic in Brownsville, had lived in Paris, and who came into the kitchen and (the high point of the book) spoke French with high school student Kazin. At the end of the chapter, Mrs. Solovey, who knew the world outside and was a sort of exile in Brownsville, commits suicide.

Summer: The Way to Highland Park: At sixteen, with the encouragement of older boys and a teacher, Kazin the reader becomes a writer. He reads in this nearly empty library. He walks outside Brownsville to Highland Park and, with his first girlfriend, strolls around the reservoir and lies in the grass, looking “across the cemetery to the skyscrapers of Manhattan.”

Kazin focuses on odors, tastes, sounds, and scenes and omits lots of details. Each paragraph and each chapter is free-flowing, and the overall organization is simple.

Dispatches, Michael Herr’s gripping memoir of covering the Vietnam War, the book on which the movie Apocalypse Now was based, seems just as random in organization—260 pages but only six chapters, roughly chronological, each chapter filled with taut anecdotes and sketches, probably the best stories from his years as a correspondent. Herr made no pretense of knitting the stories together and separated one from the next only with an extra line of space.